Abstract

Brassinosteroids (BR) play important roles in plant growth and development. Although BR receptors have been intensively studied in Arabidopsis, the BR receptors in soybean remain largely unknown. Here, in addition to the known receptor gene Glyma06g15270 (GmBRI1a), we identified five putative BR receptor genes in the soybean genome: GmBRI1b, GmBRL1a, GmBRL1b, GmBRL2a, and GmBRL2b. Analysis of their expression patterns by quantitative real-time PCR showed that they are ubiquitously expressed in primary roots, lateral roots, stems, leaves, and hypocotyls. We used rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) to clone GmBRI1b (Glyma04g39160), and found that the predicted amino acid sequence of GmBRI1b showed high similarity to those of AtBRI1 and pea PsBRI1. Structural modeling of the ectodomain also demonstrated similarities between the BR receptors of soybean and Arabidopsis. GFP-fusion experiments verified that GmBRI1b localizes to the cell membrane. We also explored GmBRI1b function in Arabidopsis through complementation experiments. Ectopic over-expression of GmBRI1b in Arabidopsis BR receptor loss-of-function mutant (bri1-5 bak1-1D) restored hypocotyl growth in etiolated seedlings; increased the growth of stems, leaves, and siliques in light; and rescued the developmental defects in leaves of the bri1-6 mutant, and complemented the responses of BR biosynthesis-related genes in the bri1-5 bak1-D mutant grown in light. Bioinformatics analysis demonstrated that the six BR receptor genes in soybean resulted from three gene duplication events during evolution. Phylogenetic analysis classified the BR receptors in dicots and monocots into three subclades. Estimation of the synonymous (Ks) and the nonsynonymous substitution rate (Ka) and selection pressure (Ka/Ks) revealed that the Ka/Ks of BR receptor genes from dicots and monocots were less than 1.0, indicating that BR receptor genes in plants experienced purifying selection during evolution.

Keywords: brassinosteroids, BR receptor, soybean, gene family, evolution

1. Introduction

The brassinosteroid (BR) phytohormones play important roles in many aspects of plant growth and development, including root growth and development [1,2], stomatal development [3], seed germination [4], skotomorphogenesis [5,6], phototropism [7], nodulation [8], immunity responses [9], and abiotic stress responses [10,11]. As early as 1990, scientists reported that BR promoted adventitious rooting in soybean hypocotyl cuttings [12]. Later work showed that BR can promote stem growth in soybean [13] and the application of BR increased soybean tolerance to drought by increasing the concentrations of soluble sugars and proline [14]. Additionally, BR increases the expression of soybean SAUR 6B, which promotes epicotyl elongation in a time-dependent manner [13]. These studies indicate that BRs regulate soybean growth, development, and stress responses at a physiological and molecular level.

Work in Arabidopsis and rice has revealed the BR signaling pathway. BR signals are detected by BR receptors such as BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE 1 (BRI1) in the cell membrane [15,16]. In the absence of BRs, BRI1 is bound by the membrane-localized BRI1 KINASE INHIBITOR 1 (BKI1) [17]. Upon perception of BR, BRI1 disassociates from BKI1 [17] and interacts with BRI1-ASSOCIATED RECEPTOR KINASE 1 (BAK1), a membrane kinase and co-receptor of BRI1 [18]. BRI1 and BAK1 trans-phosphorylate each other [17]. BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE 2 (BIN2), the downstream regulator of BRI1, is a highly conserved GSK kinase and a negative regulator of BR signaling; BIN2 phosphorylates the transcription factors BRASSINAZOLE-RESISTANT 1 (BZR1) and BZR2 thus inactivating them [19,20,21,22]. In contrast, PROTEIN PHOSPHATASE 2A (PP2A) mediates the dephosphorylation, and thus activation of BZR1 [23]. High levels of BR in plants leads to the inactivation of BIN2. The dephosphorylated BZR1 and BZR2 shuttle from the cytoplasm to the nucleus and bind to the promoters of numerous downstream genes, thus strengthening BR signaling [24]. BIN2 and BZR1 are regulated by proteasome-dependent pathways in Arabidopsis [21,25].

AtBRI1, the most important BR receptor in Arabidopsis, has a membrane-localization signal peptide in the N-terminus, 25 leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domains, and a 70-amino acid island between LRR XXI and LRR XXII [26], which is indispensable for the perception of BR [27,28]. Although BAK1 does not directly bind to BR and only has five LRR motifs, BAK1 promotes BR signaling by interacting with and phosphorylating BRI1. Two recent structural biology studies have shown that AtBRI1 is a BR receptor [27,28]. These studies revealed that brassinolide (BL) binds to a highly hydrophobic surface groove on BRI1 (LRR) and the ectodomain is crucial for the binding of BR [27,28]. This insight could be extrapolated to investigate BR receptors in agricultural plants.

Identifying BR receptors in other plants and deciphering their functions provides an important initial step toward deciphering BR signaling networks and understanding their evolution. Arabidopsis has three functional BR receptors, BRI1, BRL1, and BRL3. AtBRL2 appears to be non-functional in BR signaling [29,30]. The rice genome contains four BR receptor genes, OsBRI1, OsBRL1, OsBRL2, and OsBRL3 [31,32]. BR receptors have also been identified in tomato [33], pea [34], barley [35], cotton [36], maize [37], and wheat [38]. Although the BR signaling pathway has been well studied in Arabidopsis and rice, it is not well understood in soybean. Recent work reported that soybean Glyma06g12570 encodes a functional BR receptor [39]. Considering the high levels of duplication in the soybean genome [40], we postulated that soybean may have other functional BR receptors.

In this study, we conducted an evolutionary and functional examination of soybean BR receptors. Including the known gene Glyma06g15270 [39], we identified six BR receptor genes in the soybean genome and analyzed their expression patterns. We also further examined one gene, Glycine max Glyma04g39610 (GmBRI1b), which encodes a homolog of AtBRI1. GmBRI1b localizes to the membrane and can function as a BR receptor in Arabidopsis. Analysis of the evolution of BR receptors in plants showed that BR receptors were subjected to purifying or negative selection.

2. Results

2.1. Isolation of Glyma04g39610 (GmBRI1b)

To clone soybean brassinosteroid receptors, we used the AtBRI1 protein sequence to search the soybean EST database [41], using the BLASTP algorithm. We found that the amino acid sequence encoded by a tentative contig (TA51665) showed a high similarity to a region of AtBRI1. Therefore, we used the contig to design 5′-RACE and 3′-RACE primers to amplify the flanking regions of TA51665. After cloning and sequencing the flanking region, a cDNA fragment approximately 4 kb long containing a poly (A) tail was obtained (data not shown). Using ORF finder [42], the full cDNA was predicted to contain a long open reading frame (Genbank Accession No. KU360113) that encodes a protein of 1187 amino acids. Alignment with the soybean genome sequence indicated that this protein is encoded by Glyma04g39610 [43]. As Glyma06g15270 (GmBRI1) was reported to encode a BR receptor [39], we named Glyma04g39610 as GmBRI1b and renamed Glyma06g15270 as GmBRI1a. Further bioinformatics analysis showed that GmBRI1b contains a membrane-localized signal peptide in the N-terminus followed by 25 LRRs, a transmembrane domain, and a Ser/Thr kinase domain in the C-terminus (Table 1 and Table S1). Alignment analysis indicated that GmBRI1b has 69% and 81% identity to AtBRI1 and pea BRI1 (PsBRI1), respectively (Figure S1).

Table 1.

General information about the brassinosteroid (BR) receptor genes in soybean based on bioinformatics analysis.

| Gene | Locus | EST | TM | SP | KD | Length (AA) | Localization | Int/Ext |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GmBRI1a | Glyma06g15270 | Yes | 784..806 | 1..20 | 871..1143 | 1184 | Plas | 0/1 |

| GmBRI1b | Glyma04g39610 | Yes | 787..809 | 1..22 | 874..1146 | 1187 | Plas | 0/1 |

| GmBRL1a | Glyma04g12860 | Yes | 827..849 | 1..43 | 928..1202 | 1207 | Cyto | 0/1 |

| GmBRL1b | Glyma06g47870 | Yes | 843..865 | No | 912..1186 | 1211 | Plas | 0/1 |

| GmBRL2a | Glyma05g26771 | Yes | 752..774 | 1..32 | 756..1038 | 1053 | Nucl | 1/2 |

| GmBRL2b | Glyma08g09750 | Yes | no | 1..29 | 837..1121 | 1136 | Plas | 0/1 |

The transmembrane domains (TM) signal peptides (SP), and kinase domains (KD) were predicted by the SMART [44] program and the positions (from the amino terminus to the carboxyl terminus) of the TM, SP, and KD are indicated in the table. Putative cell localization of the soybean BR receptors was predicted by PSORT [45]. Based on the released genome sequences and cDNA sequences of soybean, the numbers of introns and exons were determined through SIM4 as described in Methods. AA, amino acid; Cyto, cytoplasm; EST, expressed sequence tag; Ext, Extron; Int, intron; Nucl, nucleus; Plas, plasmamembrane.

As reported, AtBRI1 and rice OsBRI1 lack introns [15,31]. To determine whether GmBRI1b contains introns, we designed primers covering the initiation codon and stop codon and amplified the genomic DNA. After sequencing, we found that GmBRI1b also lacks introns. This indicated that the structure of the BR receptor genes has been highly conserved between these two species.

2.2. Identification of Other BR Receptor Genes in Soybean

Given that a whole-genome duplication occurred during soybean evolution [40], we proposed that Glycine max has additional BR receptor genes. Thus, using the released soybean genome from 2010 [40], we performed a BLAST search against the soybean genome [43] using the BLASTP algorithm using the sequences of the four Arabidopsis BR receptors as queries. Apart from GmBRI1a [39] and GmBRI1b, four additional putative BR receptor genes were found, Glyma04g12860 (GmBRL1a), Glyma06g47870 (GmBRL1b), Glyma05g26771 (GmBRL2a), and Glyma0809750 (GmBRL2b) on chromosomes 4, 5, 6, and 8, respectively (Table 1). All six soybean BR receptors contain a kinase domain (KD) and five out of the six have a signal peptide (SP) and a transmembrane domain (TM) as predicted by the SMART program [44] (Table 1).

GmBRI1a, GmBRI1b, GmBRL1b, and GmBRL2b were predicted to be membrane proteins via the PSORT program [45], and GmBRL1a and GmBRL2a appeared to be localized in the cytoplasm and nucleus, respectively. In addition, five of the BR genes had no introns, but GmBRL2a had one intron (Table 1).

Next, we aligned the full amino acid sequences of the BR receptor proteins from Arabidopsis, rice, soybean, tobacco, potato, Medicago, and barley. As shown in Figure S1, the similarities between the BR receptors were as high as 80%, indicating that the BR receptors evolved slowly in higher plants. Recent structural studies indicated that the ectodomain in BR receptors is the BR-binding domain [27,28]. Thus, we compared the amino acid sequences of the ectodomains of the BR receptors from soybean, Arabidopsis, rice, barley, pea, and tomato. As expected, the similarities were high over 77% (Figure S2). Additionally, the KDs among the BR receptors from the different species were also highly conserved (data not shown), indicating the importance of KDs for BR function.

In Arabidopsis, the island domain (ID) between LLRS XXI and XXII has been reported to be involved in BR binding [27,28]. To determine whether the soybean BR receptors have the ID, we aligned the sequences with their counterparts in Arabidopsis and other species. As shown in Figure S3, the sequences of the IDs are highly conserved in BR receptors among the different species, though we did observe that the ID sequences of GmBRI2a and GmBRI2b showed more variation than those of GmBRI1a, GmBRI1b, GmBRL1a, and GmBRL1b.

To evaluate the duplication of the BR receptor genes in soybean, we used the PGDD software [46]. Three BR receptor gene duplication events were detected in soybean, GmBRI1a VS GmBRI1b, GmBRL1a VS GmBRL1b, and GmBRL2a VS GmBRL2b (Figure S4).

2.3. Transcript Levels of GmBRI1b and Other BR Receptor Genes in Soybean

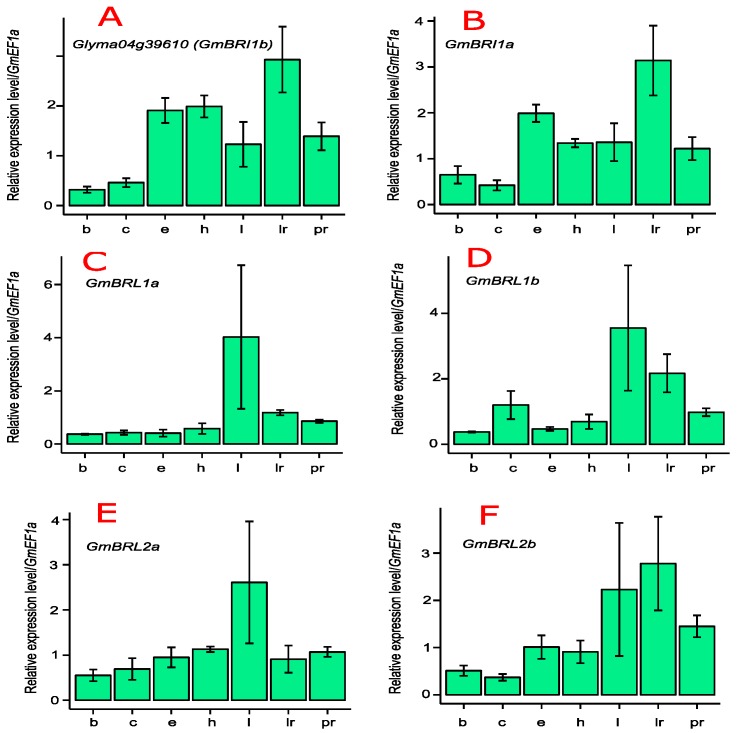

We used quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) to determine the expression patterns and transcript abundance of GmBRI1b in soybean. GmBRI1b was universally expressed in the primary roots, lateral roots, hypocotyls, epicotyls, cotyledons, apical buds, and leaves of soybean (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Expression of soybean BR receptors:GmBRI1b (A); GmBRI1a (B); GmBRL1a (C); GmBRIL1b (D); GmBRL2a (E); and GmBRL2b (F) in apical buds (b), cotyledons (c), epicotyls (e), hypocotyls (h), leaves (l), lateral roots (lr), and primary roots (pr). GmEF1a was used to normalize the qRT-PCR data. Results in (A–F) were means ± SD from three independent experiments, each of which were technically repeated three times. The normalized RNA-Seq expression data of soybean BR receptor genes were downloaded from SoyBase [47] (G).

The transcript levels of other Glycine max BR receptors from different organs were also determined through qRT-PCR. As shown in Figure 1B, the expression pattern of GmBRI1a was similar to that of GmBRI1b (Figure 1A) and the abundances of both were higher in lateral roots, as was GmBRL2b (Figure 1F). This indicates their important roles in lateral root development. Similarly, the transcript levels of GmBRL1a (Figure 1C), GmBRL1b (Figure 1D), and GmBRL2a (Figure 1E) were relatively higher in leaves.

Additionally, we investigated the expression levels of the BR receptors in soybean based on previous RNA-Seq studies [47]. As shown in Figure 1G, the transcript levels of GmBRI1a and GmBRI1b were relatively high in young leaf, flower, pod, seed, root, and nodule tissues, indicating their important roles in soybean growth and development. GmBRL1a and GmBRL1b were also expressed in all tested organs although their transcript levels were lower than those of GmBRI1a and GmBRI1b. By contrast, GmBRI2a and GmBRI2b had relatively low transcript levels in seeds and nodules (Figure 1G). The relatively high expression levels of GmBRI1a and GmBRI1b in nodules suggest their important roles in nodulation. Based on similarities of their expression patterns, the six soybean BR receptor genes can be classified into three groups, GmBRI1a and GmBRI1b; GmBRL1a and GmBRL1b; and GmBRI2a and GmBRI2b.

2.4. Subcellular Localization of GmBRI1b

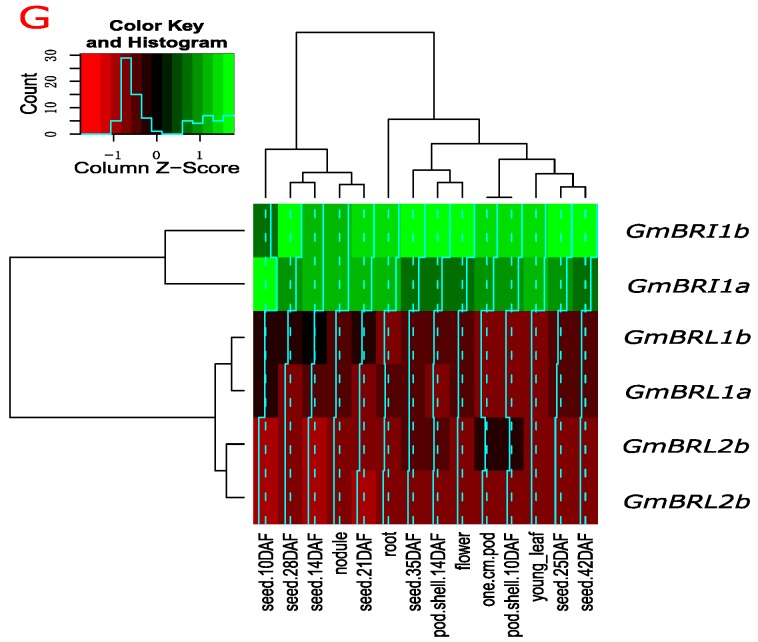

As mentioned above, a signal peptide in the N-terminus and a transmembrane (TM) domain were predicted in GmBRI1b [44] (Table 1). This indicated that GmBRI1b might be a cell membrane protein. To determine the subcellular localization of GmBRI1b, we constructed a fusion protein of GmBRI1b::GFP using the gateway vector pMDC43. We then co-transformed tobacco leaf epidermal cells with constructs encoding GmBRI1b::GFP and the plasma membrane marker protein AtPIP2A::mCherry [48]. Using laser confocal microscopy, we detected fluorescence signals only in the plasma membrane and the GFP fluorescence co-localized with mCherry fluorescence (Figure 2). This suggested that GmBRI1b is a cell membrane protein.

Figure 2.

Subcellular localization of GmBRI1b. The subcellular localization was determined with the constructs GFP::GmBRI1b: (A) GFP::BRI1b; (B) AtPIP1A::mCherry; and (C) merged image. The GFP and mCherry signals were detected at 484 and 544 nm, respectively. Scale bar = 50 µm.

2.5. Functional Analysis of GmBRI1b in Arabidopsis

BRs increase cell elongation in higher plants and a deficiency of BR results in smaller, curled leaves and shorter petioles [15]. The BR receptor AtBRI1 plays crucial roles in Arabidopsis growth and development, especially in stem and leaf growth. We hypothesized that GmBRI1b can function as a BR receptor to promote stem and leaf growth. To test this hypothesis and investigate the function of GmBRI1b, we tested whether GmBRI1b could complement the Arabidopsis BRI1 loss-of-function mutant bri1-5 bak1-1D [49]. The bri1-5 allele contains a Tyr-69 substitution at the first cysteine pair of AtBRI1 that appears to be important for its dimerization [49]. The bak1-1D line, in which expression of BAK1 is activated by an insertion of four tandem copies of the cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter, has stronger expression of BAK1, compared with wild type [18]. In contrast to the bri1-5 mutant, the bri1-5 bak1-1D mutant has a relatively higher stature and longer petioles, but still exhibits a deficiency in BR signaling, represented by relatively shorter stems and petioles relative to the Ws-2 wild type [18].

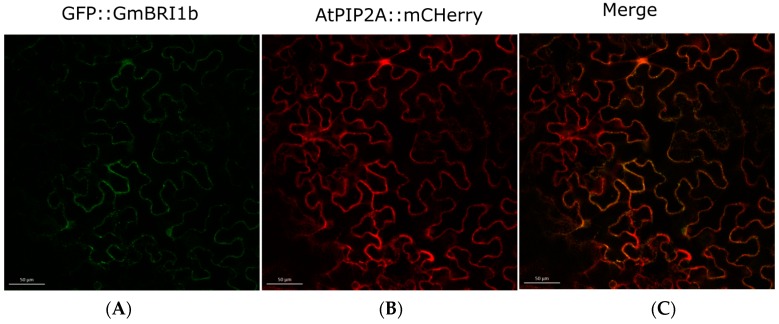

To test whether GmBRI1b can complement the Arabidopsis mutants, we created transgenic GmBRI1b over-expression lines (GmBRI1b-OX) driven by CaMV 35S promoter in the Ws-2 wild-type plants and in the bri1-5 bak1-1D mutant (Figure S5A,B). After 50 days, we measured the height of the wild-type plants, bri1-5 bak1-1D mutant, and the over-expression lines grown under the same lighting and temperature conditions. Over-expression of GmBRI1b had little effect on the height of the transgenic Ws-2 wild-type plants (Figure 3A,C). As reported, the bri1-5 bak1-1D mutant was shorter than the wild-type Ws-2 plants [18] (Figure 3B,D), but over-expression of GmBRI1b restored the normal plant height in the transgenic bri1-5 bak1-1D mutant. For example, GmBRI1b over-expression lines of the bri1-5 bak1-1D mutant were 2.6× and 2× taller compared with the non-transformed mutant (Figure 3B,D), further supporting the hypothesis that GmBRI1b functions as a BR receptor.

Figure 3.

Over-expression of GmBRI1b increased plant height in the bri1-5 bak1-1D mutant. The height of 50-day-old Ws-2 wild type and two corresponding GmBRI1b over-expression lines (GmBRI1b-OX) (A,C); and the bri1-5 bak1-1D mutant and corresponding GmBRI1b-OX lines (B,D). Results are means ± SD from five plants. Experiments were repeated two times with similar trend (Student’s t-test, ** p < 0.01).

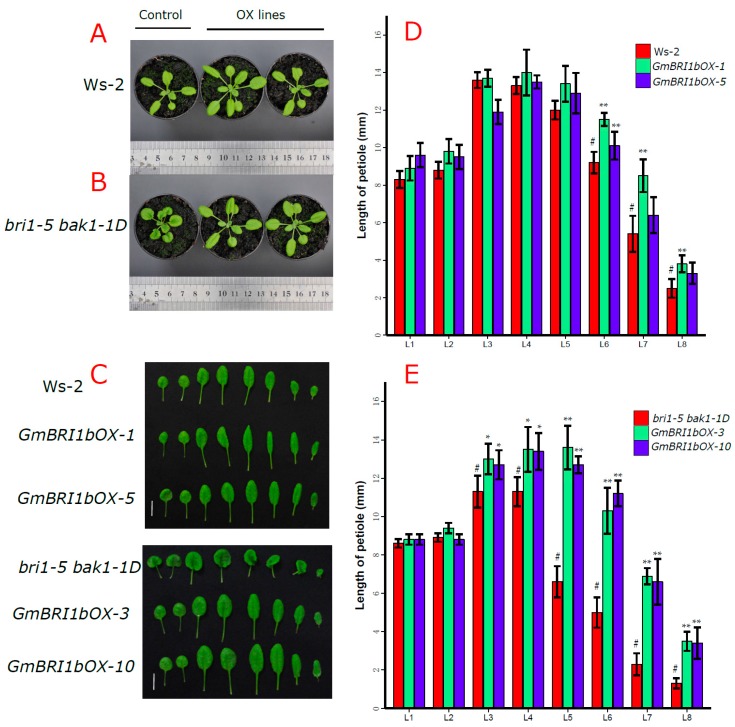

We also observed leaf and petiole growth and development in the Ws-2 wild type, and the bri1-5 bak1-1D mutant, and their corresponding GmBRI1b over-expression lines. The bri1-5 bak1-1D mutant had smaller leaves and shorter petioles compared to the Ws-2 wild type at 25 days after germination (Figure 4A), but over-expression of GmBRI1b in the transgenic bri1-5 bak1-1D mutant resulted in narrower leaves and longer petioles than in the non-transformed mutant (Figure 4A–C). Over-expression of GmBRI1b significantly increased the length of the 6th, 7th, and 8th leaf petiole in the Ws-2 wild type plants (p < 0.01), but no differences were found in the 1st to 5th leaves (Figure 4D). Over-expression of GmBRI1b in the transgenic bri1-5 bak1-1D mutant significantly increased elongation of the 3rd to the 8th leaves (p < 0.05 or p < 0.01), but not the 1st and the 2nd leaves (Figure 4E).

Figure 4.

Ectopic over-expression of GmBRI1b increased the length of the petioles in the transgenic bri1-5 bak1-1D mutant and wild type Ws-2. The 25-day-old plants (A). The 1st to the 8th leaves of the Ws-2 wild type and two corresponding GmBRI1b over-expression lines (GmBRI1b-OX) (B); and the bri1-5 bak1-1D mutant and corresponding GmBRI1b-OX lines (C). The length of the petioles from the 1st to the 8th leaves (L1-8) was measured in 25-day-old seedlings of the Ws-2 wild-type lines (D); and the bri1-5 bak1-1D mutant lines (E). Results are means ± SD from five independent experiments (in total, 25 seedlings were measured) (#, control; Student’s t-test, * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01). Scale bar = 1 cm.

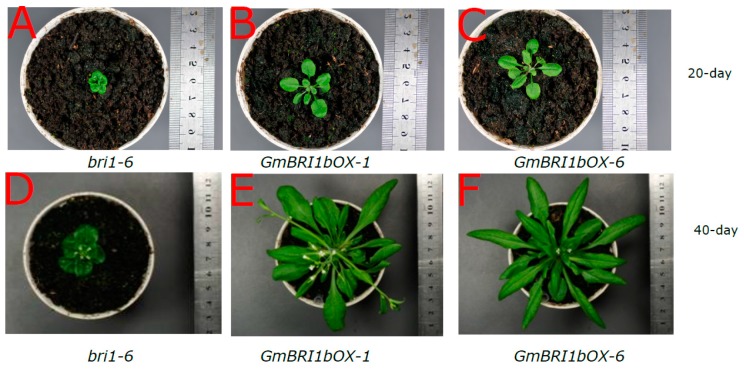

The bri1-6 mutant has smaller, curled leaves with very short petioles. Ectopic over-expression of GmBRI1b in the transgenic bri1-6 mutant (Figure S5C) significantly increased petiole length and restored the normal wild-type leaf phenotypes in 20-day-old (Figure 5A–C) and 40-day-old (Figure 5D–F) plants.

Figure 5.

Ectopic over-expression of GmBRI1b restored the wild-type leaf phenotype in the transgenic bri1-6 mutant. Leaf phenotypes of the 20-day-old bri1-6 mutant (A); and the two corresponding GmBRI1b over-expression lines GmBRI1bOX-1 (B) and GmBRI1bOX-6 (C); Leaf phenotypes of the 40-day-old bri1-6 mutant (D); and the two corresponding GmBRI1b over-expression lines GmBRI1bOX-1 (E) and GmBRI1bOX-6 (F).

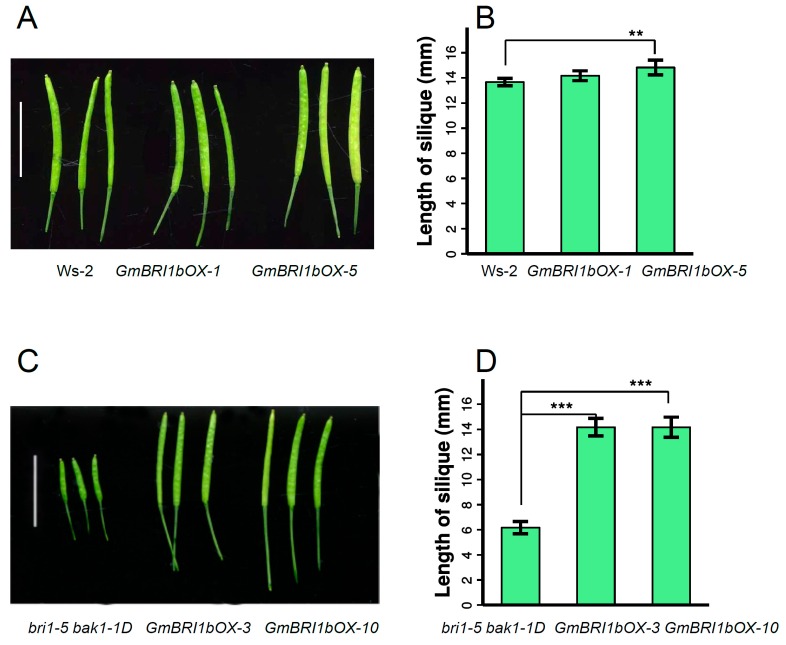

In Arabidopsis, limitations in BR levels or defects in BR signaling lead to shorter siliques [50]. The length of siliques in the same position and the same developmental stage were measured in the shoots of the Ws-2 wild type, and bri1-5 bak1-1D mutant, and their corresponding GmBRI1b over-expression lines. For the Ws-2 wild-type lines, the siliques of GmBRI1bOX-5 were significantly longer than those of the non-transformed Ws-2 wild type, but this was not true for GmBRI1bOX-1 (Figure 6A,B). For the bri1-5 bak1-1D lines, over-expression of GmBRI1b significantly increased the length of the siliques (Figure 6C,D).

Figure 6.

Over-expression of GmBRI1b increased the length of the siliques in the bri1-5bak1-1D mutant. The length of siliques in the Ws-2 wild type and the two corresponding GmBRI1b over-expression lines (GmBRI1b-OX) (A,B); and the bri1-5 bak1-1D mutant and corresponding GmBRI1b-OX lines (C,D). Results are means ± SD from three independent experiments (a total of 15 seedlings were measured) (Student’s t-test, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001). Scale bar = 1 cm.

Collectively, these results demonstrate that GmBRI1b functions as a BR receptor at the physiological and genetic level.

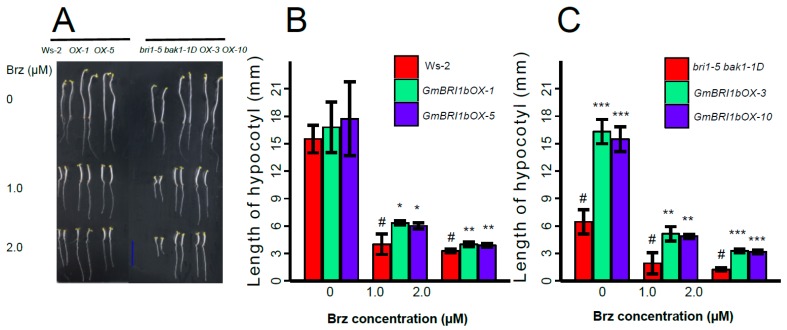

2.6. Ectopic Over-Expression of GmBRI1b Increased the Hypocotyl Length of the bri1-5 bak1-1D Mutant and Changed the Responses of the Wild Type and bri1-5 bak1-1D Mutant to Brassinazole

Brassinazole (Brz) effectively inhibits BR biosynthesis [51] and Brz treatment decreases the growth of etiolated Arabidopsis hypocotyls [51,52]. To evaluate the effects of ectopic over-expression of GmBRI1b on the response to Brz, Arabidopsis seeds were germinated in half-strength MS media and then transferred to different concentrations of Brz-containing MS media after three days. After six days, the lengths of the hypocotyls were measured.

The differences in hypocotyl lengths between the dark-grown Ws-2 wild-type plants and the two corresponding over-expression lines were not significant under the control conditions (no Brz treatment). In plants treated with 1 µM Brz, the hypocotyl lengths of the two over-expression lines were 1.58× and 1.50× longer than those of the non-transgenic Ws-2 wild-type seedlings (p < 0.05). In plants treated with 2 µM Brz, the lengths of the hypocotyls in the two over-expression lines were 1.23× and 1.19× longer than those of the non-transgenic Ws-2 wild-type seedlings (p < 0.01) (Figure 7A,B).

Figure 7.

Over-expression of GmBRI1b increased the tolerance to Brz in the Arabidopsis plants. Hypocotyl measurements were taken after exposure to different concentrations of Brz in seedlings of the Ws-2 wild type and the two corresponding GmBRI1b over-expression lines (GmBRI1b-OX) (A,B); and the bri1-5 bak1-1D mutant and corresponding GmBRI1b-OX lines (A,C). All seedlings were grown under full darkness for seven days. Results are means ± SD from three independent experiments (a total of 30 seedlings were measured) (#, control; Student’s t-test, * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001). Scale bar = 1 cm.

Ectopic over-expression of GmBRI1b in the transgenic bri1-5 bak1-1D mutant promoted hypocotyl growth in dark-grown seedlings in the untreated and Brz-treated conditions (Figure 7A,C). In the untreated plants, the hypocotyl lengths of the two over-expression lines were increased by 1.53× and 1.40× over those of the non-transformed bri1-5 bak1-1D mutant. In the plants treated with 1 µM Brz, over-expression of GmBRI1b increased the length of the hypocotyls by 1.68× and 1.54× (p < 0.01). In the plants treated with 2 µM Brz, the length of the hypocotyls in the over-expression lines increased by 1.61× and 1.53× (p < 0.01) compared with those of the bri1-5 bak1-1D mutant lacking the transgene (Figure 7C).

Taken together, these data demonstrated that ectopic over-expression of GmBRI1b decreased the sensitivity of the Ws-2 wild type and the bri1-5 bak1-1D mutant to exogenous Brz by restoring hypocotyl growth. These results further suggest that GmBRI1b functions as a BR receptor in Arabidopsis.

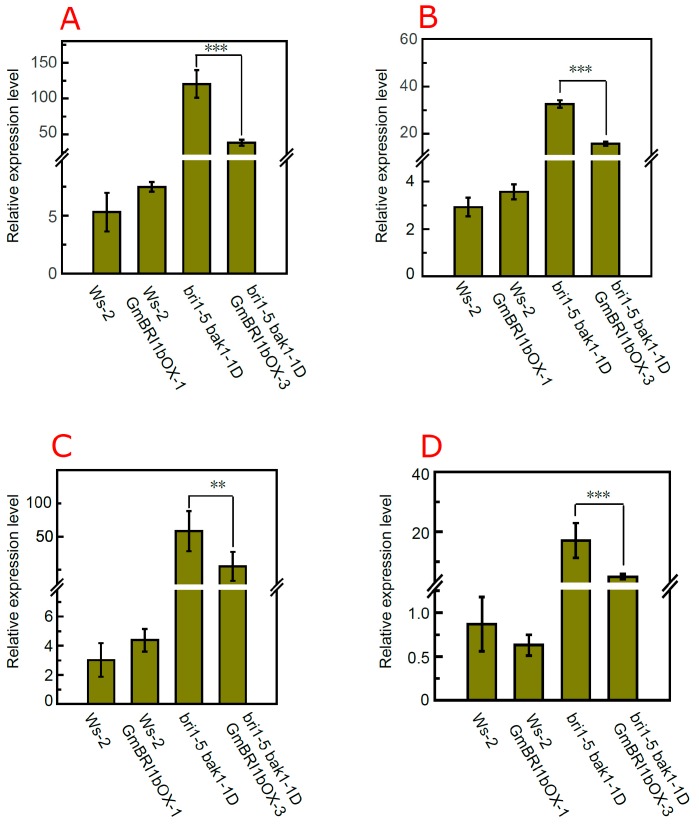

2.7. Over-Expression of GmBRI1b Altered the Expression Level of BR Biosynthesis-Related Genes in the bri1-5 bak1-1D Mutant

Previous studies have revealed that the expression levels of BR biosynthesis-related genes, such as DWF4, CPD, BR6ox-1, and BR6ox-2, are regulated by negative feedback by BR itself and by BR signaling [53,54,55]. Therefore, we selected these four marker genes to explore the effects of ectopic over-expression of GmBRI1b on the crosstalk between BR signaling and BR biosynthesis at the molecular level. Over-expression of GmBRI1b had little effect on DWF4 transcription in wild type Ws-2, but significantly down-regulated transcription of DWF4 in the transgenic bri1-5 bak1-1D mutant (Figure 8A). Dislike Ws-2, ectopic over-expression of GmBRI1b significantly repressed the expression of CPD in the bri1-5 bak1-1D over-expression line (p < 0.001, Figure 8B). Over-expression of GmBRI1b repressed the expression of BR6ox-1 in the bri1-5 bak1-1D over-expression line by 0.51× compared with the non-transformed bri1-5 bak1-1D mutant (Figure 8C). In addition, over-expression of GmBBRI1b repressed the expression of BR6ox-2 by 0.29× in the bri1-5 bak1-1D over-expression line compared with their corresponding non-transformed mutant, but this is not true in wild type (Figure 8D). Thus, these results indicate that ectopic over-expression of GmBRI1b enhanced BR signaling in the bri1-5 bak1-1D mutant, and that GmBRI1b is functional in Arabidopsis.

Figure 8.

Effect of ectopic over-expression of GmBRI1b on the expression of BR biosynthesis-related genes in the transgenic bri1-5 bak1-1D mutant. Seedlings were grown as described in Materials and Methods. qRT-PCR was used to detect the relative expression levels of: DWF4 (A); CPD (B); BR6ox-1 (C); and BR6ox-2 (D) in Ws-2 and bri1-5 bak1-1D mutant and their corresponding over-expression lines. Results are means ± SD from three independent experiments with three technical replicates (Student’s t-test, ** p< 0.01, *** p< 0.001).

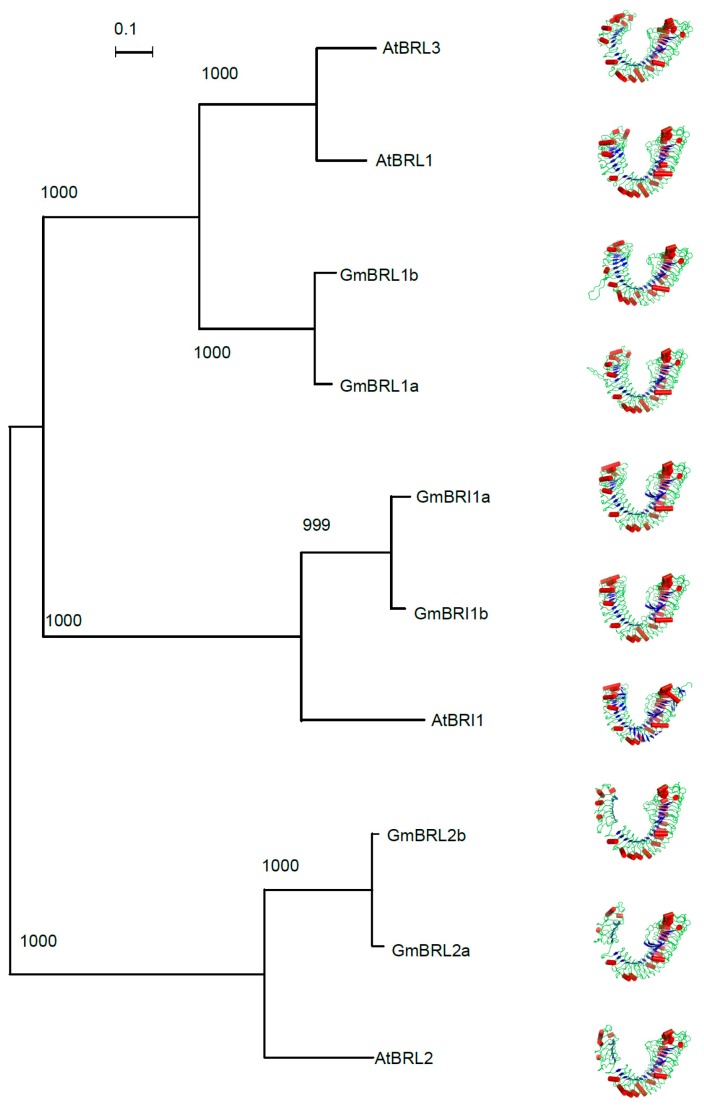

2.8. Structural Modeling of Soybean BR Receptors

Two studies reported the X-ray diffraction structure of the AtBRI1 ligand-binding domain (ectodomain) in 2011 [27,28]. In AtBRI1, a 70-amino-acid ID between LRR XXI and XXII, which folds back into the interior of the super helix, generates a pocket for binding brassinolide [27,28]. A 69 amino acid long ID was found between the LRR XXI and XXII in GmBRI1b (Table S1 and Figure S3). Computational homology modeling is a powerful tool to investigate conservation between homologous proteins across plant species [56]. After searching the PDB database [57], 3RGZ and 3RGX were selected as the best templates with which to rebuild the structure of soybean BR receptors. In addition, we also reconstructed AtBRL1, AtBRL2, and AtBRL3. As shown in Table S2, 3RGZ and 3RGX were chosen as the best templates for GmBRL1a, GmBRL1b, GmBRL2a, GmBRL2b, AtBRL1, and AtBRL3, or GmBRI1a and GmBRI1b, respectively. The related parameters in Table S2 indicated the reliability of the homology modeling.

The α-helix and β-sheet were found in the ectodomain of soybean BR receptors (Figure 9). The structural models of the Glycine max BR receptors and Arabidopsis BRL1 and BRL3 show high similarities in the 3-D structures of the ectodomains of the BR receptors. The tertiary structures of the BR receptors in each class also show high similarities (Figure 9). This suggested that the protein structures of BR receptors are conserved across plants.

Figure 9.

Structural modeling of six soybean BR receptors. The program PhyML3.0 [58] was used to reconstruct the phylogenetic tree of BR receptors from Arabidopsis and soybean. The evolutionary lineages of four BR receptors in Arabidopsis and six BR receptors in soybean were compared. The LG model for amino acid substitutions with estimated Gamma distribution was used to reconstruct the tree and the bootstrap value was set as 1000. A total of ten BR receptors were classified into Clades I, II, and III. The numbers above each branch of the tree are the bootstrap values. Scale bar indicates 0.1 amino acid substitution over evolution. In addition, the ectodomains of ten BR receptors were modeled with MODELLER9.11 software [59] based on the template of AtBRI1, which was determined with X-ray crystallization on a 3-D level in 2011 [28]. The PDB files were processed with PyMOL v1.5 software [60].

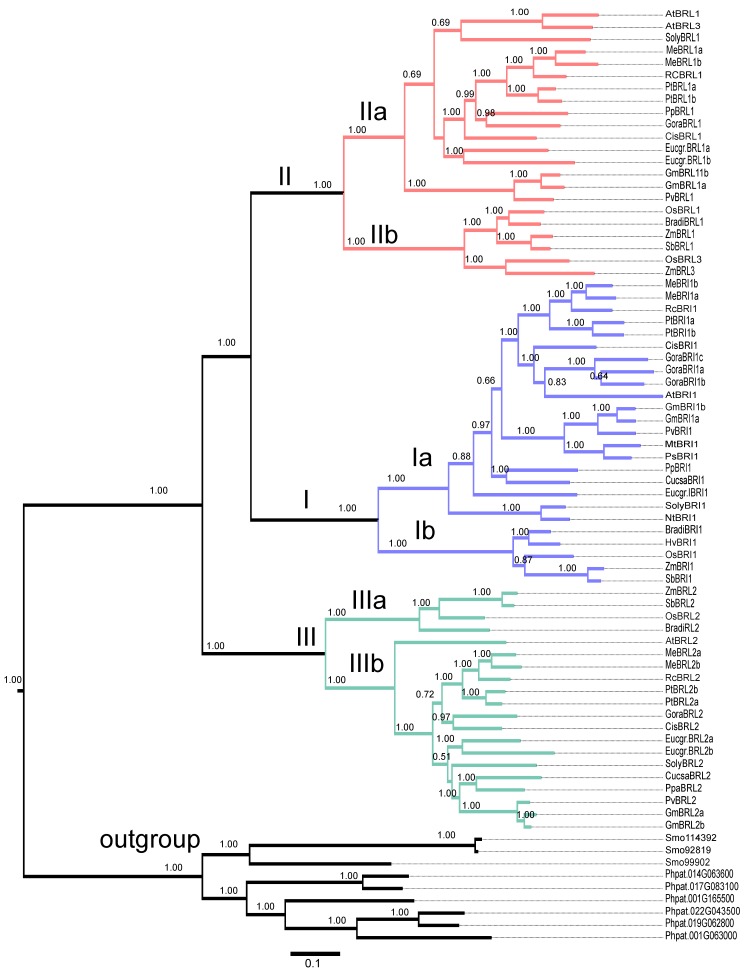

2.9. Evolutionary Analysis of BR Receptors in Plants

To analyze the evolutionary relationship among BR receptors across plant species, including receptors from moss, ferns, gymnosperms, and angiosperms, we collected BR receptor sequences using BLASTP searches. First, we performed BLAST searches against different plant genomes with the amino acid sequences of AtBRI1, AtBRL1, AtBRL2, and AtBRL3. We then selected the proteins with high scores as candidate BR receptors in the different plant species. Last, we performed domain analysis with the SMART program and predicted the kinase domain and LRR domains. Based on these criteria, the sequences of 76 putative BR proteins from Physcomitrella patens, Selaginella moelledorffii, four monocots, three legumes (Glycine max, Medicago truncatula, and Phaseolus vulgaris), and 11 dicots were aligned with ClustalW 2.1. Next, we reconstructed the phylogenetic tree of the BR receptors with MrBayes 3.2 software [61]. Three proteins from Physcomitrella patens and six from Selaginella moelledorffii were classified into the same subgroup with 100% bootstrap support (Figure 10) and were considered to be an outgroup in the reconstructed phylogenetic tree. The remaining 67 BR receptor proteins from monocots and dicots were grouped into Clades I, II, and III (100% bootstrap support). In each clade, the proteins from the monocots (rice, maize, sorghum, and Brachypodium distachyon) or from the dicots formed well-separated subclades with 100% bootstrap support (Figure 10). The branch length indicates the history of evolution.

Figure 10.

Evolutionary analysis of BR receptors in plants. BLASTP was used to search for BR receptor homologs in different plant species. A total of 76 BR receptors as shown in Spreadsheet S1 were analyzed from monocots (Oryza sativa (Os), Zea mays (Zm), Sorghum bicolor (Sb), Brachypodium distachyon (Bradi)), dicots (Arabidopsis thaliana (At), Glycine max (Gm), Solanum lycopersicum (Soly), Medicago truncatula (Mt), Phaseolus vulgaris (Pv), Populus trichocarpa (Pt), Eucalyptus grandis (Eucgr), Citrus sinensis (Cis), Gossypium raimondii (Gora), Cucumis sativa (Cusa), Prunus persica(Pp), Manihot esculenta (Me), Ricinus communis (Rc), and Nicotiana tabacum (Nt)), moss (Physcomitrella patens (Phpat)), and fern (Selaginella moelledorffii (Smo)) and grouped into three clades, CladesI, II, and III. Additionally, nine BR receptor homologs from moss and fern were determined to be members of an outgroup. The values above the branches are the probability of the bootstrap value with 1000 repeats. MrBayes 3.2 software was used to reconstruct the phylogenetic tree as described in the Methods Section. Scale bar indicates 0.1 amino acid substitution over evolution.

The three clades were represented by BRI1, BRL1/BRL3, and BRL2. As mentioned above, BRL2 in rice and Arabidopsis appeared to be non-functional. Two Glycine max BR receptors (GmBRL2a and GmBRL2b) also seemed to have no function in BR signaling. When compared with the evolutionary distance of the BR receptors from legumes and other dicots, the BR receptors from legumes showed more conservation than other BR receptors.

In addition, we also reconstructed the phylogenetic tree with the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method to reconstruct the evolutionary relationship among BR receptors with PhyML [58]. The phylogenetic tree generated with this method was the same as that generated from the Bayesian method (data not shown).

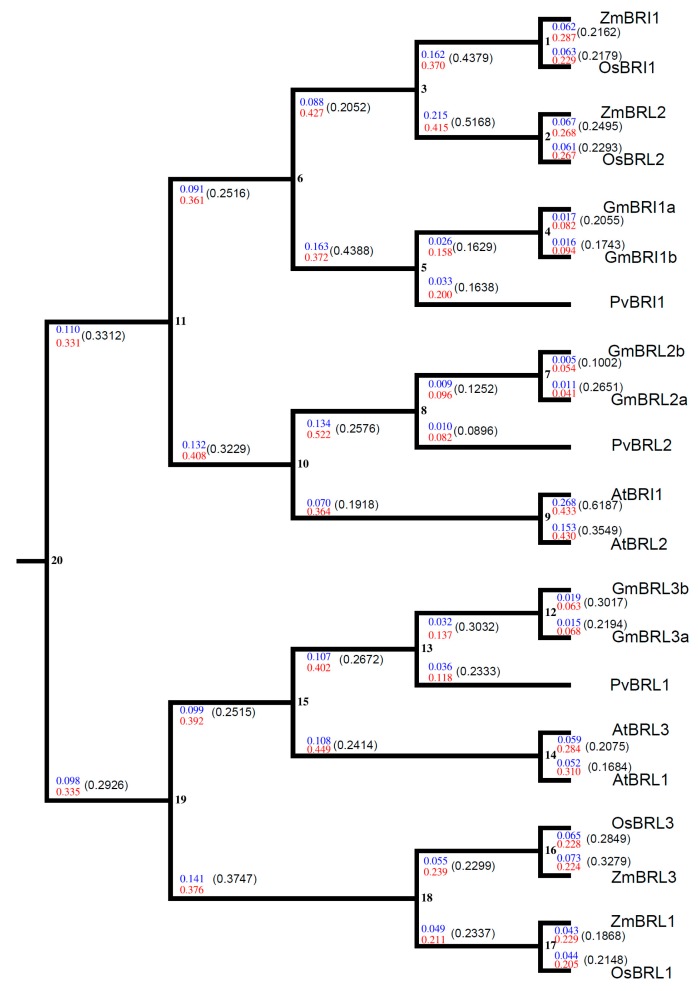

We investigated the synonymous (Ks) and nonsynonymous substitution rate (Ka) and selection pressure (Ka/Ks) of the BR receptor genes in higher plants during evolution. The aligned BR receptor amino acid sequences and their corresponding cDNA sequences that were conserved across soybean, rice, maize, Arabidopsis, and common bean were analyzed using the Ka/Ks calculator [62]. As shown in Figure 11, the Ka/Ks values in all nodes and branches were less than 1.0, indicating that BR receptors were subjected to strong selection pressure.

Figure 11.

Estimation of Ka/Ks in the BR receptor genes from soybean, common bean, Arabidopsis, rice, and maize. The cDNA sequences and amino acid sequences of the BR receptors from dicots (soybean, common bean, and Arabidopsis) and monocots (rice and maize) were used to estimate the Ka/Ks. Twenty nodes are shown. The Ka and Ks values in each node and branch are marked in blue and red, respectively. The Ka/Ks in each branch is indicated in parentheses and all Ka/Ks values were less than 1.0.

3. Discussion

Although BR signaling has been extensively studied in rice and Arabidopsis, BR signaling in soybean is still largely unknown. In this study, we cloned the soybean BR receptor gene Glyma04g39610 (GmBRI1b) and demonstrated that it functions as a BR receptor in Arabidopsis at the physiological, genetic, and molecular levels. In addition to this BR receptor gene and another known soybean BR receptor gene Glymg06g15270 [39], we identified four other soybean BR receptor genes.

BRs play important roles in plant growth, development, and stress adaptations such as cell elongation and division, seed germination, photomorphogenesis and skotomorphorgenesis, responses to salts and heavy metals, and pathogen resistance. BRs have been found in 61 species of embryophytes, including 53 angiosperms, six gymnosperms, one pteridophyte (Equisetum arvense), and one bryophyte (Marchantia polymorpha) [63]. Additionally, two single-celled green freshwater algae (Chlorophyta; Chlorella vulgaris and Hydrodictyon reticulatum) and the marine brown alga Cystoseira myrica biosynthesize BRs [64]. This indicates that BRs appear to be conserved phytohormones in plants. Considering that BRs even exist in single-celled plants, the identification of BR receptor-like proteins in moss and fern may deepen our understanding of the evolution of BR signaling in plants. Our phylogenetic analysis implies that BR receptors exist universally throughout the plant kingdom (Figure 10).

Similar to previously reported BR receptor genes in Arabidopsis and rice [15,31], GmBRI1b does not contain introns. We determined that at least six BR receptor genes exist in the soybean genome, in contrast to only four BR receptor genes in both Arabidopsis and rice, indicating that BR signaling may be more complex in soybean. In addition, two soybean BR receptor genes, GmBRL2a and GmBRL2b, showed a close evolutionary relationship with AtBRL2 and OsBRL2, which have been reported to have no function in BR signaling [29,32]. The role of soybean GmBRI2a and GmBRI2b in BR signaling needs further study.

As previously reported, functional BR receptors in Arabidopsis and rice are localized in cell membranes [31,65]. A signal peptide was found in the N-terminus of GmBRI1b (Table 1). GFP fusion experiments showed that GmBRI1b localizes in the plasma membrane (Figure 2). This supports the idea that GmBRI1b perceives BR at the cell membrane.

AtBRI1 and OsBRI1 are ubiquitously expressed in all tissues [31,65]. We found that GmBRI1b is expressed in apical buds, cotyledons, epicotyls, hypocotyls, leaves, lateral roots, and primary roots (Figure 1A), implying a crucial and universal role in soybean growth and development. The soybean RNA-Seq data [47] supported our results (Figure 1G). Moreover, the transcript abundance of two soybean BR receptor genes, GmBRI1a and GmBRI1b, in nodules was relatively high, suggesting that these two genes play important roles in nodulation (Figure 1G). Application of Brz on mature leaves or into the culture media increased the nodule number and inhibited internode growth in the soybean cultivar Enrei and foliar applications of BR inhibited nodulation and root growth in the super-nodulating mutant En6500, indicating the existence of BR signaling modules in soybean [66]. Moreover, these results indicate that endogenous BR homeostasis or BR signaling might control nodulation. Recent studies demonstrated that pea BR biosynthesis mutant (lk), and BR receptor mutant (lkb) had fewer lateral roots and nodules and the decreased nodule number did not seem to be attributed to changes in endogenous GA or auxin levels [8]. Therefore, the roles of BR receptors in legume nodulation need further study.

In our study, we noticed differences in expression among the soybean BR receptors. For instance, the expression levels of GmBRL2a and GmBRL2b were very low in seeds, but the levels of GmBRI1a and GmBRI1b were higher in seeds (Figure 1G). We also found higher expression of GmBRI1a and GmBRI1b in flowers (Figure 1G), indicating that these genes might regulate flower and seed development. The highest expression of GhBRI1 was found in hypocotyls, while its transcripts were much lower in mature roots [36]. GmBRI1a was found to be highly expressed in soybean hypocotyls and is up-regulated by exogenous BR [39]. We detected higher expression of GmBRI1b in hypocotyls and lateral roots in fourteen-day-old soybean seedlings, in which active cell proliferation and elongation are occurring. A previous study showed that some gene pairs resulting from gene duplication in soybean showed similar expression patterns during nodulation, while others showed different expression patterns [67]. Interestingly, we found that three BR receptor gene pairs generally showed similar transcription patterns (Figure 1A–F). As three gene duplication events occurred during soybean evolution (Figure S4), it is possible that the promoter sequences in the three gene pairs are similar and some common cis-elements might be found among them.

The loss of function mutation in BR signaling or biosynthesis genes in Arabidopsis results in a dwarf phenotype and late flowering [6,68,69,70]. We found that ectopic over-expression of GmBRI1b in transgenic bri1-6, and bri1-5 bak1-1D mutant restored the normal wild-type phenotype, including the height of the seedlings and the length of petioles and siliques, leaf growth. Thus, we concluded that GmBRI1b functions as a BR receptor in Arabidopsis at the physiological and genetic level. We also demonstrated that GmBRI1b acts as a functional BR receptor in Arabidopsis at the molecular level. Ectopic over-expression of GmBRI1b repressed the relatively high expression of DWF4, CPD, BR6OX-1, and BR6OX-2 in the transgenic bri1-5 bak1-1D mutant. GmBRI1a was classified into the same subclade with GmBRI1b in this study. In a previous study, when GmBRI1a was expressed in the Arabidopsis bri1-5 mutant, reversed the developmental defects of the bri1-5 mutant [39], although the subcellular localization of GmBRI1a was not determined [39]. The BR-binding activity of GmBRI1b remains unknown. Results from this study combined with previous studies suggest that GmBRIa and GmBRI1b are BR receptors.

Domain analysis showed that GmBRI1b contains an N-terminal signal peptide, a transmembrane domain, a kinase domain, and 25 LRR motifs (Table 1 and Table S1). This is in accordance with the structures of AtBRI1 and GmBRI1a [39]. We noticed that in higher plants, the complete BR receptor domains evolved through two domain-gain events in the ancestral receptor-like kinase, the juxtamembrane domain (JM) and the island domain (ID) [71]; the JM domain was acquired during the early diversification of plants and the ID domain formed in the ancestors of angiosperms and gymnosperms after their divergence from moss [71].

Based on structural biology studies conducted in 2012 [27,28], the ectodomain is responsible for the binding of the BR receptor to brassinolide. As expected, the highly conserved ectodomain sequences of the soybean BR receptors with BR receptors of other plant species were observed (Figure S2). Moreover, our structural modeling indicates that the ectodomain of all six soybean BR receptors form similar tertiary structures to that of AtBRI1 (Figure 9). This indicates that the ectodomain of BR receptors in Glycine max might have an identical function to that of AtBRI1 in vivo.

The amino acid sequences in the IDs between different plant species are highly conserved and IDs participate directly in BR binding [27,38]. The results in Figure S3 show that the ID in soybean BR receptors is highly conserved, but the ID in GmBRL2a andGmBRL2b show more variation than the other four soybean BR receptors. GmBRL2a and GmBRL2b were classified into the same subclade with AtBRL2, which have been documented to have no function in BR signaling [29]. This raises the question of whetherGmBRL2a and GmBRL2b play a role in BR signaling, and if no, can this be ascribed to the differences in the IDs? Of note, IDs only exist in gymnosperms (conifers and gnetophytes) and angiosperms. In contrast, the more ancient plant LRR–KD domain configuration generated from green algae after the split between the green algae and red algae [71].

We investigated the evolution of BR receptors in plants. BLAST searches indicated that a similar kinase existed in lower plants such as Physcomitrella patens and Selaginella moelledorffii. This is consistent with a previous study that suggested that the kinase domain (KD) is more ancient [71]. When we reconstructed the phylogenic tree, we found that the proteins from Physcomitrella patens and Selaginella moelledorffii had a close relationship, although we did not identify conserved BR receptors in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Considering the existence of BRs in single-celled plants [64], we can not rule out the existence of BR receptor-like proteins in single-celled plants as some receptor kinase proteins might act as BR receptors. Interestingly, Cheon et al. [72] reported that Selaginella lacks a homolog of AtBRI1, but does have downstream proteins such as BIN2, BSU1, and BZR1. This implies that the BR receptor complex evolved in a common ancestor of lycophytes, gymnosperms, and angiosperms. We found that a total of 67 BR receptors from dicots and monocots can be evolutionarily grouped into three clades represented by AtBRI1/OsBRI1, AtBRL1/OsBRL1, and AtBRL2/OsBRL2 with significant bootstrap support, which is in accordance with a previous study [72]. Each clade can be divided into two subclades, Ia, Ib, IIa, IIb, IIIa, and IIIb (100% bootstrap support), one subclade from monocots, and the other from dicots (Figure 10). These results indicate that three ancestral BR receptor genes might generate a plethora of BR genes in plants. One subgroup, which was represented by AtRBL2, might have lost its BR receptor function during evolution [29], but the reason for this is currently unknown.

We analyzed the selection pressure of BR receptors in plants during evolution. Notably, in each clade, the Ka/Ks was less than 1.0 (Figure 11). This suggests that the BR receptor genes in higher plants were subjected to negative or purifying selection during evolution and indicates that the amino acid residues in BR receptor proteins are important and that a nonsynonymous mutation would be lethal or harmful for species survival. A previous study showed that the Dn/Ds values were less than 1.0 in all gene pairs and detected no positive selection during BR receptors evolution [71]. Similarly, the substitution ratio of non-synonymous to synonymous SNPs (Ka/Ks) of as high as 76% analyzed JAZ genes across 13 monocot and dicot species was less than 1.0 [73]. Additionally, the Ka/Ks of the squamosa promoter binding protein (SBP)-box genes that encodes crucial transcription factors in plants were less than 0.5 [74]. Our results are in accordance with previous reports that the Ka/Ks of some important genes in multiple plant species are less than 1.0 [75].

In the case of soybean, BR receptors have undergone duplication due to whole-genome duplication events [40]. The soybean genome duplication also makes it much more difficult to identify BR-insensitive mutants. The CRISPR-Cas9 tool, together with artificial microRNA to knock out or knock down genes, would be valuable to further study other soybean BR receptor genes and for investigations of BR receptor functions in soybean.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Growth

Glycine max cultivar BD2 was used as the soybean material. One week after germination, soybean plants were cultured with half-strength Hoagland’s solution in the greenhouse. The wild type Arabidopsis Ws-2, and the bri1-5 bak1-D and bri1-6 mutants were used. Seeds were stratified in the dark at 4 °C for 2 days, then surface-sterilized for 30 s in 75% ethanol followed by 8–10 min in 10% NaClO solution and washed five times with sterilized distilled water, then plated on half-strength MS media containing 1% sucrose and 0.8% agar with a pH of 5.8. Plates were kept in a growth chamber with a 16-h light/8-h dark cycle and a temperature cycle of 23 °C light/21 °C dark. After one week, seedlings were transplanted into soil and cultured as indicated above.

4.2. Extraction of Genomic DNA and RNA and Reverse Transcription of mRNA

Soybean and Arabidopsis genomic DNA and RNA were extracted with the CTAB and TRIzol methods, respectively. The cDNAs were reverse transcribed through MLV-transcriptase according to the vendor’s instructions. Other molecular experimental procedures were based on standard methods.

4.3. RACE Cloning of GmBRI1b

Two-week-old soybean BD2 seedlings were used to extract total RNA with the TRIzol method. Reverse transcription was carried out following standard methods to obtain cDNA. We used the SMART RACE kit (Takara Biomedical Technology, Beijing, China) to clone the GmBRI1b cDNA 5′ fragments and 3′fragments. Specific primer pairs were designed with PerlPrimer [76] and are listed in Table S3.

4.4. Analysis of Expression Patterns of Soybean BR Receptor Genes

We designed specific primer pairs with PerlPrimer [76] based on the cDNA sequences and genomic sequences [43] of the six soybean BR receptors to detect the expression levels of the six genes in different organs. Seven-day-old seedlings of the soybean cultivar BD2 germinated on sands were transferred to half-strength Hoagland’s nutrient solution. Seven days later, the roots, stems, and leaves were sampled for extraction of total RNA. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was used to test the expression levels of the six BR receptor genes. The PCR thermal cycler parameters used were 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for15 s, and 72 °C for 30 s. GmEF1a (Glyma19g07240) was used to normalize the expression levels. We used Rotorgen software and absolute quantification method [77] to calculate the PCR results with the amplicon of GmEF1a as standard. The data presented were from three independent biological experiments.

4.5. Over-Expression of GmBRI1b in Arabidopsis

The plasmid pCHF3 (a gift from Christian Fankhauser) was digested with EcoRI and SalI to release the CaMV 35S constitutive promoter and then the 35S promoter was ligated with the EcoRI and SalI-digested plasmid pPZP221 (a gift from Jianming Li). We named this plasmid p35SPZP221. We amplified GmBRI1bcDNA, which contains SalI and SmaI restriction sites, with primer pairs. Next, we ligated GmBRI1b with plasmid p35SPZP221 digested with SalI and SmaI. After sequencing, Arabidopsis wild-type Ws-2, the bri1-5 bak1-1D and bri1-6 mutants were transformed with Agrobacterium GV3101 via the floral dipping method [78]. Then, the transgenic seedlings were screened in half-strength MS media that was solidified with 0.8% agar and contained 100 mg/L gentamycin. The homozygous, one-copy insertion transgenic lines were confirmed with PCR and the χ2-test and the qualifying over-expression lines were used for further experiments.

4.6. Subcellular Localization of GmBRI1b

To determine the subcellular localization of GmBRI1b, we constructed the fusion protein of GmBRI1b with GFP. The ORF of GmBRI1b, in which no stop codon exists, was amplified by PCR using the primers 5′-GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTTCATGAAAGCTCTGTACAGAAGCT-3′ and 5′-GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTCCTAATGCTTGCTCAATTCAGGG-3′. The amplified cDNA fragment was then recombined into the pMDC43 vector, thus producing the GFP::BRI1b construct under the control of the 35S promoter. AtPIP2A, which was shown to be a plasma membrane aquaporin [48], fused with mCherry was used as the plasma membrane marker protein. Agrobacterium tumefaciens mediated transient expression in Nicotiana benthamiana tobacco leaves was conducted as described [79] with minor modifications. The Agrobacterium GV3101 strain harboring the constructs of GFP::GmBRI1b and AtPIP2A-mCherry [56] was inoculated in YEP medium with the appropriate antibiotics and incubated for 16 h with shaking at 28 °C. After centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 10 min, the cell pellet was re-suspended to OD600 = 1.0 in the infiltration medium (10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM MES, and 150 µM acetosyringone). The cell suspension was then allowed to standing at 22 to −24 °C for 2 to 3 h before infection into the tobacco leaves. A mix of cells containing the same quantities of GFP::GmBRI1b and AtPIP2A-mCherry, were then infiltrated into the leaves of three- to four-week-old tobacco plants. After three days, we observed the fluorescence distribution in the tobacco epidermal cells at 488 nm (GFP) and 587 nm (mCherry) wave lengths by confocal laser scanning microscopy (LSM780, Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

4.7. Phenotypic Analysis of Transgenic Arabidopsis

For sterilized solid media culture, seeds were sterilized as described above and sown in solid half-strength MS medium containing 0, 1, or 2 µM Brz. Then, the square petri dishes were wrapped with double layers of foil and were placed vertically in full darkness. After 7 days, the seedlings were scanned and analyzed with ImageJ software to quantify the length of the hypocotyls.

For determination of height, silique length, and petiole length, the seeds of the wild-type Ws-2, the bri1-6 and bri1-5 bak1-1D mutants, and their corresponding over-expression lines were stratified at 4 °C for 2 days to break dormancy and then sown in soil. After the culture period, the height of the plants and the length of the petioles and siliques were measured.

4.8. Determination of the Expression Levels of BR Biosynthesis-Related Genes in the Wild Type, the Mutant, and Their Corresponding over-Expression Lines

To determine the expression levels of the BR biosynthesis-related genes CPD, DWF4, BR6ox-1, and BR6ox-2, seedlings of one-week-old Ws-2 wild type, and bri1-5 bak1-1D mutant, and the over-expression lines were transplanted into soil for one month under standard growth conditions. Then, whole plants were used to extract total RNA with the TRIzol method. cDNAs were obtained by reverse transcriptase reactions. qRT-PCR was used to determine the transcript abundances of CPD, DWF4, BR6ox-1, and BR6ox-2. AtEF-1a was used as a reference gene to normalize the qRT-PCR results. The qRT-PCR data were determined by absolute quantification method [77] with the amplicon of AtEF-1a as standard. Specific primer pairs are listed in Table S3.

4.9. Determination of the GmBRI1b Structure

Based on the full sequence of the GmBRI1b cDNA, we designed primers at the regions of the initiation codon and the stop codon to amply the genomic DNA fragment. After sequencing, we compared the genomic and cDNA sequences of GmBRI1b using SIM4 software [80] to determine the protein structure of GmBRI1b.

4.10. Alignment of BR Receptors

T-coffee software [81] was used to align the sequences of the full BR receptor, ectodomain, and island domain of the BRs from the different plant species Glycine max, Arabidopsis thaliana, Solanum lycopersicum, Oryza sativa, Pisum sativum, Hordeum vulgare, and Medicago truncatula.

4.11. Structural Modeling of Soybean BR Receptors

The sequences of the ectodomain of AtBRI1, AtBRL1, AtBRL3, and the six soybean BR receptors were aligned with T-coffee v11.0 [81]. We then searched for the best-scoring templates in the Protein Data Bank [57] and selected 3RGXZ and 3RGXA. Next, we rebuilt nine structural models (six soybean BR receptors, AtBRL1, AtBRL3, and AtBRL2) of each ectodomain using Modeller v9.10 [56,82] and reported the results using the best model based on the DOPE score [83]. The PDB files and images were processed with PyMOL v1.5 [60].

4.12. Estimation of Selection and Substitution Rates

The cDNA and amino acid sequences of the BR receptors from the monocots rice and maize and the dicots soybean, common bean, and Arabidopsis were used to calculate nonsynonymous (Ka) and synonymous (Ks) substitution rates and their ratio (Ka/Ks) for each node/branch via a Ka/Ks online calculator tool [84].

4.13. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed with Excel 2003. The Student’s t-test was used to compare the differences. R 3.0.1 package [85], gplots [86], and ggplot2 [87] were used to draw the heatmap and other figures.

5. Conclusions

Glyma04g39610 encodes GmBRI1b, which functions as a BR receptor. GmBRI1b is cell membrane protein. Ectopic over-expression of GmBRI1b in bri1-6 and bri1-5 bak1-1D rescues the BR signaling-related growth and development defects of the two mutants. The Glycine max genome contains six BR receptor-encoding genes, which are grouped into three clades and are generated from three gene duplication events during evolution. BR receptors in plants were subjected to purifying selection during evolution.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NSFC (No. 31071848). We are in debt to Jianming Li for his critical comments and suggestions during the early stage of this study and for providing the bri1-6 seeds. We thank Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (ABRC) for providing bri1-5 bak1-1D (CS6126) seeds and Jennifer Mach for her comments and help in English writing.

Abbreviations

| AA | Amino acid |

| BAK1 | BRI1 ASSOCIATED RECEPTOR KINASE 1 |

| BIN2 | BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE2 |

| BKI1 | BRI1 KINASE INHIBITOR 1 |

| BR | Brassinosteroid |

| BRI1 | BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE 1 |

| Brz | Brassinazole |

| BZR1 | BRASSINAZOLE-RESISTANT1 |

| ID | Island domain |

| ORF | Open reading frame |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative real-time PCR |

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials can be found at http://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/17/6/897/s1.

Author Contributions

Suna Peng participated in the study design, carried out the experiments and data analysis, and drafted the manuscript; Ping Tao, Feng Xu, Aiping Wu, and Weige Huo carried out the experiments and analyzed data; and Jinxiang Wang conceived, designed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Müssig C., Shin G.H., Altmann T. Brassinosteroids promote root growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2003;133:1261–1271. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.028662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hacham Y., Holland N., Butterfield C., Ubeda-Tomas S., Bennett M.J., Chory J., Savaldi-Goldstein S. Brassinosteroid perception in the epidermis controls root meristem size. Development. 2011;138:839–848. doi: 10.1242/dev.061804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim T.W., Michniewicz M., Bergmann D.C., Wang Z.Y. Brassinosteroid regulates stomatal development by GSK3-mediated inhibition of a MAPK pathway. Nature. 2012;482:419–422. doi: 10.1038/nature10794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leubner-Metzger G. Brassinosteroids and gibberellins promote tobacco seed germination by distinct pathways. Planta. 2001;213:758–763. doi: 10.1007/s004250100542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chory J., Nagpal P., Peto C.A. Phenotypic and genetic analysis of det2, a new mutant that affects light-regulated seedling development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1991;3:445–459. doi: 10.1105/tpc.3.5.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szekeres M., Németh K., Koncz-Kálmán Z., Mathur J., Kauschmann A., Altmann T., Rédei G.P., Nagy F., Schell J., Koncz C. Brassinosteroids rescue the deficiency of cyp90, a cytochrome p450, controlling cell elongation and de-etiolation in Arabidopsis. Cell. 1996;85:171–182. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bai M.Y., Fan M., Oh E., Wang Z.Y. A triple helix-loop-helix/basic helix-loop-helix cascade controls cell elongation downstream of multiple hormonal and environmental signaling pathways in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2012;24:4917–4929. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.105163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferguson B.J., Ross J.J., Reid J.B. Nodulation phenotypes of gibberellin and brassinosteroid mutants of pea. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:2396–2405. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.062414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakashita H., Yasuda M., Nitta T., Asami T., Fujioka S., Arai Y., Sekimata K., Takatsuto S., Yamaguchi I., Yoshida S. Brassinosteroid functions in a broad range of disease resistance in tobacco and rice. Plant J. 2003;33:887–898. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dhaubhadel S., Browning K.S., Gallie D.R., Krishna P. Brassinosteroid functions to protect the translational machinery and heat-shock protein synthesis following thermal stress. Plant J. 2002;29:681–691. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bajguz A., Hayat S. Effects of brassinosteroids on the plant responses to environmental stresses. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2009;47:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sathiyamoorthy P., Nakamuracohen S. In vitro root induction by 24-epibrassinolide on hypocotyl segments of soybean [Glycine max (l.) merr.] Plant Growth Regul. 1990;9:73–76. doi: 10.1007/BF00025281. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zurek D.M., Rayle D.L., McMorris T.C., Clouse S.D. Investigation of gene expression, growth kinetics, and wall extensibility during brassinosteroid-regulated stem elongation. Plant Physiol. 1994;104:505–513. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.2.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang M., Zhai Z., Tian X., Duan L., Li Z. Brassinolide alleviated the adverse effect of water deficits on photosynthesis and the antioxidant of soybean (Glycine max L.) Plant Growth Regul. 2008;56:257–264. doi: 10.1007/s10725-008-9305-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li J., Chory J. A putative leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase involved in brassinosteroid signal transduction. Cell. 1997;90:929–938. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80357-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Z.Y., Nakano T., Gendron J., He J., Chen M., Vafeados D., Yang Y., Fujioka S., Yoshida S., Asami T., et al. Nuclear-localized BZR1 mediates brassinosteroid-induced growth and feedback suppression of brassinosteroid biosynthesis. Dev. Cell. 2002;2:505–513. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00153-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang X., Chory J. Brassinosteroids regulate dissociation of BKI1, a negative regulator of BRI1 signaling, from the plasma membrane. Science. 2006;313:1118–1122. doi: 10.1126/science.1127593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li J., Wen J., Lease K.A., Doke J.T., Tax F.E., Walker J.C. BAK1, an Arabidopsis LRR receptor-like protein kinase, interacts with BRI1 and modulates brassinosteroid signaling. Cell. 2002;110:213–222. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00812-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li J., Nam K.H., Vafeados D., Chory J. BIN2, a new brassinosteroid-insensitive locus in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2001;127:14–22. doi: 10.1104/pp.127.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li J., Nam K.H. Regulation of brassinosteroid signaling by a GSK3/SHAGGY-like kinase. Science. 2002;295:1299–1301. doi: 10.1126/science.1065769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He J.X., Gendron J.M., Yang Y., Li J., Wang Z.Y. The GSK3-like kinase BIN2 phosphorylates and destabilizes BZR1, a positive regulator of the brassinosteroid signaling pathway in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:10185–10190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152342599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao J., Peng P., Schmitz R.J., Decker A.D., Tax F.E., Li J. Two putative BIN2 substrates are nuclear components of brassinosteroid signaling. Plant Physiol. 2002;130:1221–1229. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.010918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tang W., Yuan M., Wang R., Yang Y., Wang C., Oses-Prieto J.A., Kim T.W., Zhou H.W., Deng Z., Gampala S.S., et al. PP2A activates brassinosteroid-responsive gene expression and plant growth by dephosphorylating BZR1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;13:124–131. doi: 10.1038/ncb2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yin Y., Vafeados D., Tao Y., Yoshida S., Asami T., Chory J. A new class of transcription factors mediates brassinosteroid-regulated gene expression in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2005;120:249–259. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peng P., Yan Z., Zhu Y., Li J. Regulation of the Arabidopsis GSK3-like kinase BRASSINOSTEROID-INSENSITIVE 2 through proteasome-mediated protein degradation. Mol. Plant. 2008;1:338–346. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssn001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang X., Li X., Meisenhelder J., Hunter T., Yoshida S., Asami T., Chory J. Autoregulation and homodimerization are involved in the activation of the plant steroid receptor BRI1. Dev. Cell. 2005;8:855–865. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hothorn M., Belkhadir Y., Dreux M., Dabi T., Noel J.P., Wilson I.A., Chory J. Structural basis of steroidhormone perception by the receptor kinase BRI1. Nature. 2011;474:467–471. doi: 10.1038/nature10153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.She J., Han Z., Kim T.W., Wang J., Cheng W., Chang J., Shi S., Wang J., Yang M., Wang Z.Y., et al. Structural insight into brassinosteroid perception by BRI1. Nature. 2011;474:472–476. doi: 10.1038/nature10178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cano-Delgado A., Yin Y., Yu C., Vafeados D., Mora-Garcia S., Cheng J.C., Nam K.H., Li J., Chory J. BRL1 and BRL3 are novel brassinosteroid receptors that function in vascular differentiation in Arabidopsis. Development. 2004;131:5341–5351. doi: 10.1242/dev.01403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou A., Wang H., Walker J.C., Li J. BRL1, a leucine-rich repeat receptor-like protein kinase, is functionally redundant with BRI1 in regulating Arabidopsis brassinosteroid signaling. Plant J. 2004;40:399–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamamuro C., Ihara Y., Wu X., Noguchi T., Fujioka S., Takatsuto S., Ashikari M., Kitano H., Matsuoka M. Loss of function of a rice brassinosteroid insensitive1 homolog prevents internode elongation and bending of the lamina joint. Plant Cell. 2000;12:1591–1606. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.9.1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakamura A., Fujioka S., Sunohara H., Kamiya N., Hong Z., Inukai Y., Miura K., Takatsuto S., Yoshida S., Ueguchi-Tanaka M., et al. The role of OsBRI1 and its homologous genes, OsBRL1 and OsBRL3, in rice. Plant Physiol. 2006;140:580–590. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.072330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Montoya T., Nomura T., Farrar K., Kaneta T., Yokota T., Bishop G.J. Cloning the tomato Curl3 gene highlights the putative dual role of the leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase tBRI1/SR160 in plant steroid hormone and peptide hormone signaling. Plant Cell. 2002;14:3163–3176. doi: 10.1105/tpc.006379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nomura T., Bishop G.J., Kaneta T., Reid J.B., Chory J., Yokota T. The LKA gene is BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE 1 homolog of pea. Plant J. 2003;36:291–300. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chono M., Honda I., Zeniya H., Yoneyama K., Saisho D., Takeda K., Takatsuto S., Hoshino T., Watanabe Y. A semidwarf phenotype of barley uzu results from a nucleotide substitution in the gene encoding a putative brassinosteroid receptor. Plant Physiol. 2003;133:1209–1219. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.026195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sun Y., Fokar M., Asami T., Yoshida S., Allen R.D. Characterization of the brassinosteroid insensitive 1genes of cotton. Plant Mol. Biol. 2004;54:221–232. doi: 10.1023/B:PLAN.0000028788.96381.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kir G., Ye H., Nelissen H., Neelakandan A.K., Kusnandar A.S., Luo A., Inzé D., Sylvester A.W., Yin Y., Becraft P.W. RNA interference knockdown of BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE1 in maize reveals novel functions for brassinosteroid signaling in controlling plant architecture. Plant Physiol. 2015;169:826–839. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Navarro C., Moore J., Ott A., Baumert E., Mohan A., Gill K.S., Sandhu D. Evolutionary, comparative and functional analyses of the brassinosteroid receptor gene, BRI1, in wheat and its relation to other plant genomes. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:897. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang M., Sun S., Wu C., Han T., Wang Q. Isolation and characterization of the brassinosteroid receptor gene (GmBRI1) from Glycine max. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014;15:3871–3888. doi: 10.3390/ijms15033871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schmutz J., Cannon S., Schlueter J., Ma J., Mitros T. Genome sequence of the palaeopolyploid soybean. Nature. 2010;463:178–183. doi: 10.1038/nature08670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Childs K.L., Hamilton J.P., Zhu W., Ly E., Cheung F., Wu H., Rabinowicz P.D., Town C.D., Buell C.R., Chan A.P. The TIGR plant transcript assemblies database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D846–D851. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wheeler D.L., Chappey C., Lash A.E., Leipe D.D., Madden T.L., Schuler G.D., Tatusova T.A., Rapp B.A. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:10–14. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goodstein D.M., Shu S., Howson R., Neupane R., Hayes R.D., Fazo J., Mitros T., Dirks W., Hellsten U., Putnam N., et al. Phytozome: A comparative platform for green plant genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D1178–D1186. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Letunic I., Doerks T., Bork P. SMART: Recent updates, new developments and status. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D257–D260. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Horton P., Park K.J., Obayashi T., Fujita N., Harada H., Adams-Collier C.J., Nakai K. WoLF PSORT: Protein localization predictor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W585–W587. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee T.H., Tang H., Wang X., Paterson A.H. PGDD: A database of gene and genome duplication in plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D1152–D1158. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Severin A.J., Woody J.L., Bolon Y.T., Joseph B., Diers B.W., Farmer A.D., Muehlbauer G.J., Nelson R.T., Grant D., Specht J.E., et al. RNA-Seq atlas of Glycine max: A guide to the soybean transcriptome. BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10:897. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nelson B.K., Cai X., Nebenführ A. A multicolored set of in vivo organelle markers for co-localization studies in Arabidopsis and other plants. Plant J. 2007;51:1126–1136. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Noguchi T., Fujioka S., Choe S., Takatsuto S., Yoshida S., Yuan H., Feldmann K.A., Tax F.E. Brassinosteroid-insensitive dwarf mutants of Arabidopsis accumulate brassinosteroids. Plant Physiol. 1999;121:743–752. doi: 10.1104/pp.121.3.743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li J., Jin H. Regulation of brassinosteroid signaling. Trends Plant Sci. 2007;12:37–41. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nagata N., Min Y.K., Nakano T., Asami T., Yoshida S. Treatment of dark-grown Arabidopsis thaliana with a brassinosteroid-biosynthesis inhibitor, brassinazole, induces some characteristics of light-grown plants. Planta. 2000;211:781–790. doi: 10.1007/s004250000351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang X., Kota U., He K., Blackburn K., Li J., Goshe M.B., Huber S.C., Clouse S.D. Sequential transphosphorylation of the BRI1/BAK1 receptor kinase complex impacts early events in brassinosteroid signaling. Dev. Cell. 2008;15:220–235. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mathur J., Molnár G., Fujioka S., Takatsuto S., Sakurai A., Yokota T., Adam G., Voigt B., Nagy F., Maas C., et al. Transcription of the Arabidopsis CPD gene, encoding a steroidogenic cytochrome p450, is negatively controlled by brassinosteroids. Plant J. 1998;14:593–602. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1998.00158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bancos S., Nomura T., Sato T., Molnár G., Bishop G.J., Koncz C., Yokota T., Nagy F., Szekeres M. Regulation of transcript levels of the Arabidopsis cytochrome p450 genes involved in brassinosteroid biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2002;130:504–513. doi: 10.1104/pp.005439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tanaka K., Asami T., Yoshida S., Nakamura Y., Matsuo T., Okamoto S. Brassinosteroid homeostasis in Arabidopsis is ensured by feedback expressions of multiple genes involved in its metabolism. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:1117–1125. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.058040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pieper U., Webb B.M., Barkan D.T., Schneidman-Duhovny D., Schlessinger A., Braberg H., Yang Z., Meng E.C., Pettersen E.F., Huang C.C., et al. ModBase, a database of annotated comparative protein structure models, and associated resources. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D465–D474. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Berman H.M., Westbrook J., Feng Z., Gilliland G., Bhat T.N., Weissig H., Shindyalov I.N., Bourne P.E. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guindon S., Dufayard J.F., Lefort V., Anisimova M., Hordijk W., Gascuel O. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: Assessing the performance of PhyML3.0. Syst. Biol. 2010;59:307–321. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fiser A., Do R.K., Sali A. Modeling of loops in protein structures. Protein Sci. 2000;9:1753–1773. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.9.1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.PyMOL The PyMOL molecular graphics system, version 1.5.0. [(accessed on 3 July 2012)]. Available online: https://www.pymol.org.

- 61.Huelsenbeck J.P., Ronquist F. Mrbayes: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:754–755. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Suyama M., Torrents D., Bork P. PAL2NAL: Robust conversion of protein sequence alignments into the corresponding codon alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W609–W612. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kutschera U., Wang Z.Y. Brassinosteroid action in flowering plants: A Darwinian perspective. J. Exp. Bot. 2012;63:3511–3522. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hayat S., Ahmad A. Brassinosteroids: A Class of Plant Hormone. Springer; Heidelberg, Germany: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Friedrichsen D.M., Joazeiro C.A., Li J., Hunter T., Chory J. Brassinosteroid-insensitive-1 is a ubiquitously expressed leucine-rich repeat receptor serine/threonine kinase. Plant Physiol. 2000;123:1247–1256. doi: 10.1104/pp.123.4.1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Terakado J., Fujihara S., Goto S., Kuratani R., Suzuki Y., Yoshida S., Yoneyama T. Systemic effect of a brassinosteroid on root nodule formation in soybean as revealed by the application of brassinolide and brassinazole. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2005;51:389–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0765.2005.tb00044.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Libault M., Joshi T., Takahashi K., Hurley-Sommer A., Puricelli K., Blake S., Finger R.E., Taylor C.G., Xu D., Nguyen H.T., et al. Large-scale analysis of putative soybean regulatory gene expression identifies a Myb gene involved in soybean nodule development. Plant Physiol. 2009;151:1207–1220. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.144030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li J., Nagpal P., Vitart V., McMorris T.C., Chory J. A role for brassinosteroids in light-dependent development of Arabidopsis. Science. 1996;272:398–401. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5260.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Choe S., Dilkes B.P., Fujioka S., Takatsuto S., Sakurai A., Feldmann K.A. The DWF4 gene of Arabidopsis encodes a cytochrome p450 that mediates multiple 22α-hydroxylation steps in brassinosteroid biosynthesis. Plant Cell. 1998;10:231–243. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bishop G.J., Harrison K., Jones J.D. The tomato Dwarf gene isolated by heterologous transposon tagging encodes the first member of a new cytochrome p450 family. Plant Cell. 1996;8:959–969. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.6.959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang H., Mao H. On the origin and evolution of plant brassinosteroid receptor kinases. J. Mol. Evol. 2014;78:118–129. doi: 10.1007/s00239-013-9609-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cheon J., Fujioka S., Dilkes B.P., Choe S. Brassinosteroids regulate plant growth through distinct signaling pathways in Selaginella and Arabidopsis. PLoS ONE. 2013;12:897. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Singh A.P., Pandey B.K., Deveshwar P., Narnoliya L., Parida S.K., Giri J. JAZ repressors: Potential involvement in nutrients deficiency response in rice and chickpea. Front. Plant Sci. 2015;6:975. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang S.D., Ling L.Z., Yi T.S. Evolution and divergence of SBP-box genes in land plants. BMC Genom. 2015;16:787. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1998-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Victoria F.C., Bervald C.M., daMaia L.C., deSousa R.O., Panaud O., deOliveira A.C. Phylogenetic relationships and selective pressure on gene families related to iron homeostasis in land plants. Genome. 2012;55:883–900. doi: 10.1139/gen-2012-0064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Marshall O.J. PerlPrimer: Cross-platform, graphical primer design for standard, bisulphite and real-time PCR. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:2471–2472. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schmittgen T.D., Zakrajsek B.A., Mills A.G., Gorn V., Singer M.J., Reed M.W. Quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction to study mRNA decay: Comparison of endpoint and real-time methods. Anal. Biochem. 2000;285:194–204. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Clough S.J., Bent A.F. Floral dip: A simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16:735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Liu T.Y., Huang T.K., Tseng C.Y., Lai Y.S., Lin S.I., Lin W.Y., Chen J.W., Chiou T.J. PHO2-dependent degradation of PHO1 modulates phosphate homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2012;24:2168–2183. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.096636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Florea L., Hartzell G., Zhang Z., Rubin G. M., Miller W. A computer program for aligning a cDNA sequence with a genomic DNA sequence. Genome Res. 1998;8:967–974. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.9.967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Notredame C., Higgins D.G., Heringa J. T-coffee: A novel method for fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;302:205–217. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sali A., Blundell T.L. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 1993;234:779–815. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shen M.Y., Sali A. Statistical potential for assessment and prediction of protein structures. Protein Sci. 2006;15:2507–2524. doi: 10.1110/ps.062416606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Liberles D.A. Evaluation of methods for determination of a reconstructed history of gene sequence evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2001;18:2040–2047. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. [(accessed on 10 September 2012)]. Available online: http://www.R-project.org/

- 86.Warnes G.R., Bolker B., Bonebakker L., Gentleman R., Huber W., Liaw W., Lumley T., Maechler M., Magnusson A., Moeller S., et al. gplots: Various R programming tools for plotting data. [(accessed on 12 January 2014)]. Available online: http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=gplots.

- 87.Wickham H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer; New York, NY, USA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.