Abstract

The active medicinal constituents in Hypericum perforatum, used to treat depression and skin irritation, include flavonoids and xanthones. The carbon skeletons of these compounds are formed by chalcone synthase (CHS) and benzophenone synthase (BPS), respectively. Polyclonal antisera were raised against the polyketide synthases from Hypericum androsaemum and their IgG fractions were isolated. Immunoblotting and immunotitration were used to test the IgGs for crossreactivity and monospecificity in H. perforatum leaf protein extract. Immunofluorescence localization revealed that both CHS and BPS are located in the mesophyll. The maximum fluorescence levels were observed in approx. 0.5 and 1 cm long leaves, respectively. The fluorescence intensity observed for CHS significantly exceeded that for BPS. Using histochemical staining, flavonoids were detected in the mesophyll, indicating that the sites of biosynthesis and accumulation coincide. Our results help understand the biosynthesis and underlying regulation of active H. perforatum constituents.

Keywords: Hypericum perforatum, chalcone synthase, benzophenone synthase, polyketide synthases, immunofluorescence localization, histochemical localization, flavonoids, xanthones

Introduction

Medications containing extracts from the flowering upper parts of the medicinal plant Hypericum perforatum (St. John’s wort; Hypericaceae) are used for the treatment of mild to moderate depressions as well as skin irritations and infected wounds (Linde et al., 2008; Wölfle et al., 2014). Due to the additive and synergistic effects of the ingredients, the entire extract is commonly used for therapy. The major active constituents involve hyperforins, hypericins, flavonoids, and xanthones (Beerhues, 2011). All these four classes of compounds are polyketide derivatives. Crucial steps of their biosynthetic pathways are catalyzed by polyketide synthase (PKS) enzymes. Plant PKSs (type III) are homodimers. Either subunit has an independent active site, which accommodates the starter and extender substrates (Austin and Noel, 2003). Variations in the starter molecule, the number of extender units and the mode of cyclization result in the formation of an amazing array of PKS products.

The PKSs that are involved in hyperforin, hypericin, flavonoid, and xanthone biosyntheses are isobutyrophenone, octaketide, chalcone, and benzophenone synthases, respectively (Beerhues, 2011). cDNAs encoding benzophenone synthase (BPS) and chalcone synthase (CHS) were cloned from elicitor-treated Hypericum androsaemum cell cultures and greenhouse-grown H. sampsonii plants and were functionally expressed in Escherichia coli (Liu et al., 2003; Huang et al., 2012). BPS and CHS catalyze decarboxylative condensations of benzoyl-CoA and 4-coumaroyl-CoA, respectively, with three molecules of malonyl-CoA. While benzoyl-CoA is also preferred by BPS from Garcinia mangostana, the enzyme from Centaurium erythraea uses 3-hydroxybenzoyl-CoA (Beerhues, 1996; Nualkaew et al., 2012). The products of the BPS and CHS reactions are benzophenones and chalcones, which are metabolized to xanthones and flavonoids, respectively (Winkel-Shirley, 2001; El-Awaad et al., 2016). Upon mutation in a single active site position, H. androsaemum BPS formed phenylpyrones (Klundt et al., 2009). Xanthones and flavonoids contribute to the medicinal effects of H. perforatum extracts. Understanding their biosynthetic pathways in H. perforatum requires, in addition to the knowledge of the individual biochemical reactions, information about the spatial and temporal regulation, which underlies the metabolic routes. Here, immunofluorescence localization of BPS and CHS in leaves of H. perforatum is reported.

The two other PKSs, isobutyrophenone and octaketide synthases, were not included in this study. No cDNA encoding isobutyrophenone synthase, the key enzyme of hyperforin biosynthesis, has so far been isolated. For octaketide synthase, cDNAs were cloned from various species, including H. perforatum (Abe et al., 2005; Karppinen et al., 2008; Mizuuchi et al., 2009). However, all the recombinant proteins form an incorrectly cyclized octaketide derivative. Correct cyclization leading to formation of emodin anthrone has recently been observed in elicitor-treated Cassia bicapsularis cell cultures (Abdel-Rahman et al., 2013). Octaketide synthase transcripts in H. perforatum leaves were localized by in situ hybridization, indicating their exclusive presence in hypericin-containing dark nodules (Karppinen et al., 2008). Therefore, octaketide synthase was not considered here.

In the present study, we focus on the localization of BPS and CHS. Antibodies were raised, tested for their specificities and used for immunofluorescence detection of the PKSs in the mesophyll of H. perforatum leaves. Furthermore, biosynthetic products were histochemically localized. While a specific stain for xanthones was not available, flavonoids were detected in the mesophyll.

Materials and Methods

Plants

Hypericum perforatum L. (Hypericaceae) was grown in the medicinal plants garden of the Institute of Pharmaceutical Biology, Technische Universität Braunschweig, Germany.

Chemicals and Materials

Solvents and chemicals were of either analytical or high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) grade. Polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) blotting membranes (Immobilon P) were purchased from Millipore (Bedford, USA). Enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) Western blotting detection reagents were ordered from GE Healthcare (Freiburg, Germany). Peroxidase-conjugated AffinPure goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) and Alexa Fluor 488-goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) were obtained from Dianova (Hamburg, Germany) and Invitrogen (Karlsruhe, Germany), respectively. Cryo-embedding material and poly-L-lysine-coated slides were purchased from Plano (Marburg, Germany) and Roth (Karlsruhe, Germany), respectively. Polyclar AT and diphenylboric acid 2-aminoethyl ester (DPBA) were ordered from Serva (Heidelberg, Germany) and Sigma-Aldrich (Taufkirchen, Germany), respectively.

Generation of Polyclonal Antisera and Purification of IgG Fractions

The BPS and CHS sequences used were from H. androsaemum (Liu et al., 2003). They were expressed as both His6-tag and GST-fusion proteins using pRSET B (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) and pGEX (Görlach and Schmid, 1996) expression vectors, respectively. The proteins were purified by affinity chromatography using Ni–NTA agarose and GSTrap matrices, respectively (Liu et al., 2003, 2007). The His6-tag proteins were used for immunization of rabbits, which was carried out by SEQLAB Sequence Laboratories (Göttingen, Germany). The IgG fractions of the antisera and the pre-immune sera were isolated and stored, as described previously (Chizzali et al., 2012).

Protein Extraction and Immunoblotting

Fresh leaves (1 g) of varying size (0.3, 0.5, 0.8, 1.5, and 2.0 cm) were frozen in liquid nitrogen, ground in a mortar, mixed with 10% (w/v) Polyclar AT and extracted on ice for 10 min with 1 ml 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4 containing 10 mM 1,4-dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.5 mM sucrose and 1 mM phenylmethane sulphonyl fluoride (protease inhibitor). The homogenate was centrifuged at 8,900 g for 25 min and the supernatant was used for immunoblotting. Protein concentration was determined by the method of Bradford (1976). Soluble proteins were separated on a 12% (w/v) sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) polyacrylamide gel and electroblotted on a PVDF membrane, as described previously (Chizzali et al., 2012). After blocking, the membrane was incubated with anti-His6–BPS IgG (1:100,000 v/v) and anti-His6–CHS IgG (1:10,000 v/v). Incubation with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG and further processing were carried out, as described previously (Chizzali et al., 2012). As control for efficient blotting, the membrane and the gel were stained with Indian ink and Coomassie blue solutions, respectively.

Enzyme Assays

The incubation mixtures (250 μL) consisted of 0.1 M potassium phosphate pH 7.0, 324 μM malonyl-CoA and 2 μg protein. In addition, the BPS and CHS assays contained 54 μM benzoyl-CoA and 4-coumaroyl-CoA, respectively. After incubation at 30°C for 10 min, the enzymatic products were extracted and analyzed by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), as described previously (Liu et al., 2003).

Immunotitration

Mixtures of enzyme solution (50 μl) and IgG solution (50 μl of 1:2 to 1:512 dilutions) were incubated for 20 min at room temperature (Beerhues and Wiermann, 1988). Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (50 μl) containing 6% (w/v) polyethylene glycol 8000 was added. Following incubation at 4°C over night, the mixtures were centrifuged for 10 min at 8,700g. An aliquot of the supernatant (100 μl) was used to determine the non-precipitated enzyme activity that remained in the supernatant. Controls without antibody and with 1:2 to 1:512 dilutions of the pre-immune IgG were included.

Immunofluorescence Localization of BPS and CHS

For tissue fixation, the method of Moll et al. (2002) was used, except for slight modifications adapted to H. perforatum tissue. Small segments (1.2 mm2) were immediately fixed for 2 h under reduced pressure (0.3 mbar) in ice-cold buffered fixative solution, which consisted of 2% w/v formaldehyde (freshly prepared from paraformaldehyde), 0.1% v/v glutaraldehyde and 0.1% v/v Triton X-100 in 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.2. After washing with PBS (2 × 10 min), the samples were dehydrated in a graded ethanol series (30, 50, 70, and 90% for 30 min each at room temperature). For cryosectioning, fixed and PBS-washed tissue was embedded in a cryo-embedding matrix and stored in a cool and dry place. The specimens were cut to thin segments (18–20 μm) using a cryomicrotome (HM 500 O cryostate, Microme). The sections were transferred to poly-L-lysine-coated slides, dried and further treated, as described previously (Chizzali et al., 2012). The pre-immune IgG and His6-tag IgG fractions were used in 1:10 to 1:100 dilutions. Goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody was conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488, which exhibits absorbance of blue light at 494 nm and emission of green light at 517 nm.

Histochemical Localization of Flavonoids

Fresh hand-sectioned leaves were stained for 5 min with 0.125% (w/v) diphenylboric acid 2-aminoethyl ester (DPBA) in 0.005% (v/v) Triton X-100 and washed in water for 2 min. Images were taken using the confocal laser scanning microscope cLSM-510META (Release Version 4.2 SP1), connected to an Axiovert 200M (Carl Zeiss). The specimens were examined either using the Plan-Neofluar 10×/0.3 for overview or the C-Apochromat 40×/1.2 water-immersion objective for detailed pictures. The settings were as follows. Flavonoid staining was recorded using the 488 nm argon-laser (14% intensity) and chlorophyll autofluorescence was recorded using the 633 nm Helium laser (45% intensity) for excitation in the multi-tracking mode. The emitted light passed the primary beam splitting mirrors UV/488/543/633 and was detected after splitting with the NFT-545 on BP 505–550 for flavonoid staining and LP 650 for chlorophyll detection, respectively. When appropriate, the bright-field images of samples were visualized using the transmitted light photomultiplier. The lambda-mode was used to examine the spectral signature of fluorophores. All images were processed using the LSM Image Browser Release 4.2 (Carl Zeiss).

Results

Antisera and Isolated IgG Fractions

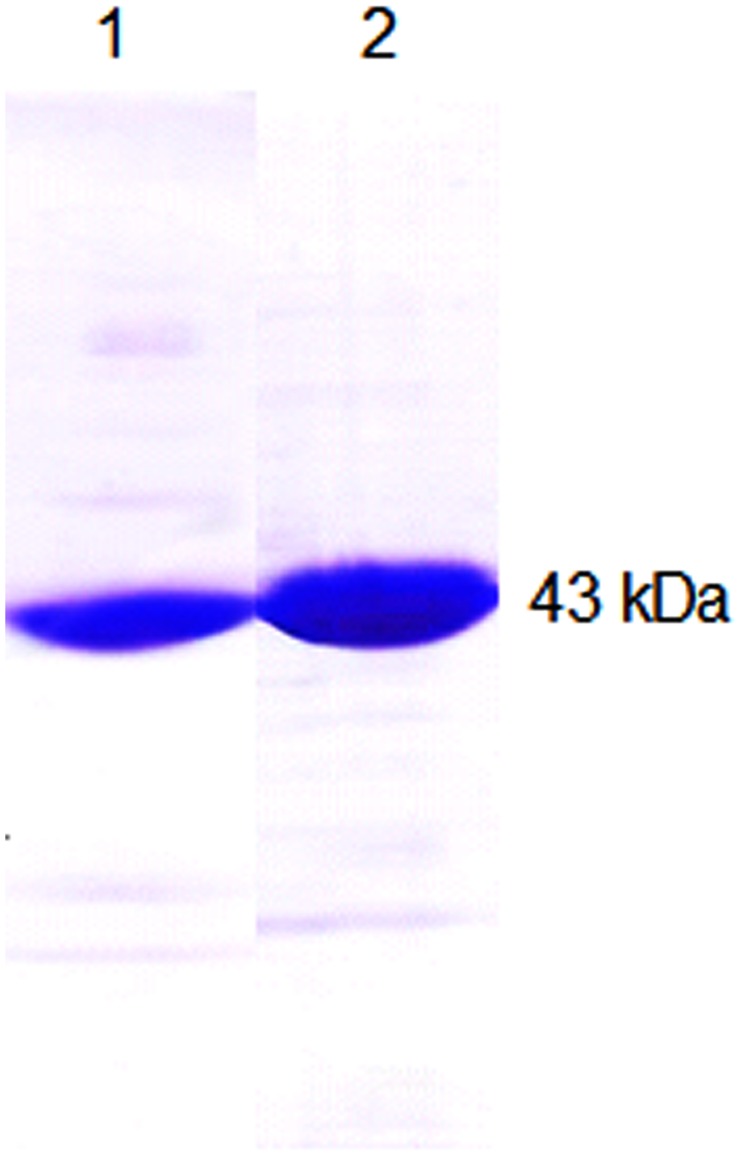

To raise antibodies against BPS and CHS, the coding sequences of the proteins from H. androsaemum (Liu et al., 2003) were expressed in E. coli to yield both His6-tag and GST-fusion proteins. Affinity chromatography on Ni–NTA and GSTrap matrices, respectively, resulted in proteins of near-homogeneity each, as indicated by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (Figure 1). The His6-tag proteins served to raise polyclonal antisera in rabbits and the IgG fractions were isolated from both the pre-immune sera and the antisera. When studied by SDS–PAGE, the heavy and light chains at 50 and 25 kDa, respectively, were the only bands detectable. The isolated IgG fractions were tested for crossreactivity and monospecificity.

FIGURE 1.

Overexpression and affinity chromatography yielded proteins for immunization of rabbits. Purified His6– benzophenone synthase (BPS) (1) and His6– chalcone synthase (CHS) (2) were run on a sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) polyacrylamide gel, indicating near-homogeneity each.

Lack of Crossreactivity between BPS and CHS Antibodies

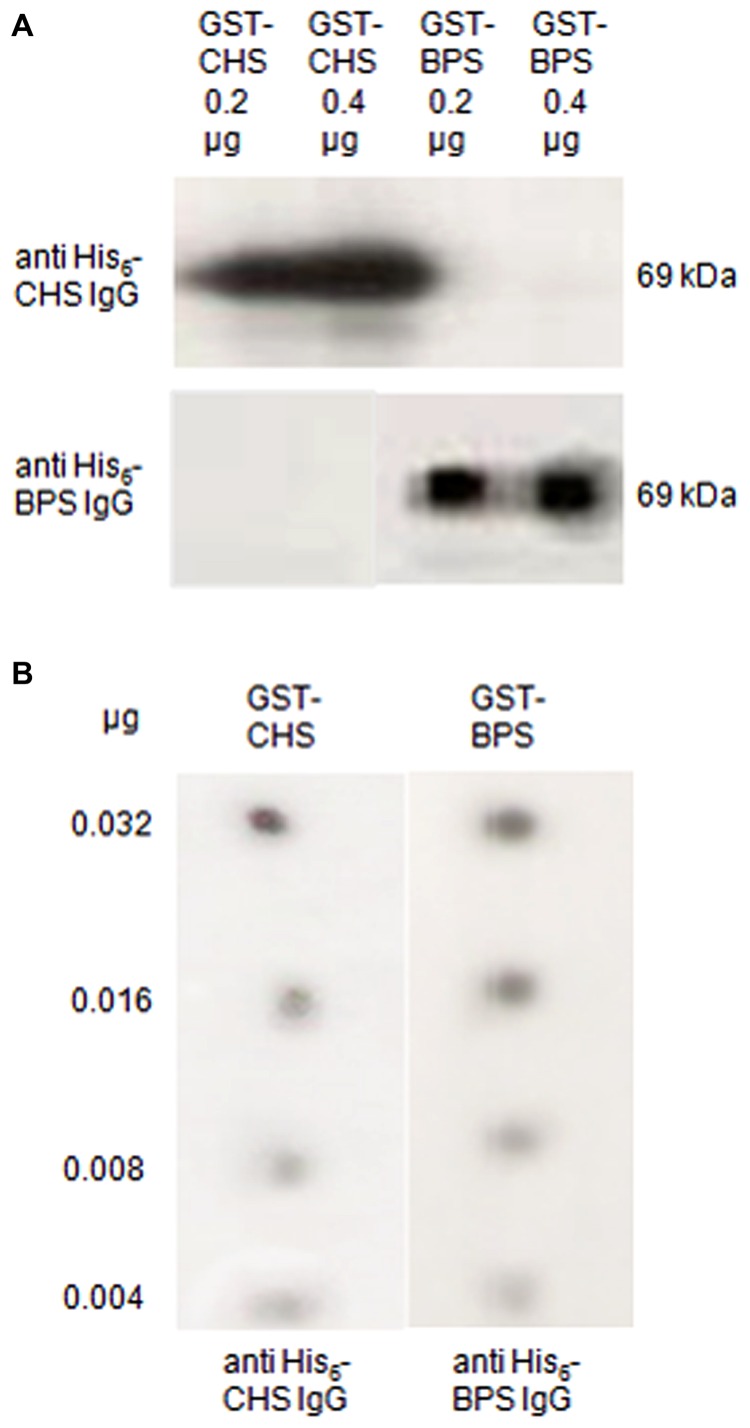

Parallel immunolocalization of BPS and CHS requires that the antibodies do not crossreact with the respectively other antigen. Immunoblotting and immunotitration were used to study the specificities of the IgG fractions isolated. To rule out that cross-reactions in the polyclonal antisera occur between the His6 tag and His6-tag-directed antibodies, the GST-fusion proteins were used as antigens.

In immunoblotting after SDS–PAGE of the affinity-purified GST-fusion proteins, anti-His6–CHS detected GST–CHS (69 kDa) but anti-His6–BPS did not (Figure 2A). Conversely, anti-His6–BPS stained GST–BPS (69 kDa) but anti-His6–CHS did not. Thus, no crossreactivity was observed in immunoblotting. The pre-immune IgG fractions failed to cause any immunoreactions.

FIGURE 2.

The BPS and CHS antibodies lacked crossreactivity and resembled in detection sensitivity. (A) Immunoblotting of CHS and BPS. The GST-fusion proteins were run on a SDS polyacrylamide gel, blotted on a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane and incubated with the antibodies raised against the His6-tag proteins. (B) Dot blotting. Decreasing quantities of the GST-fusion proteins were dotted on a PVDF membrane and immunostained with anti-His6–CHS IgG and anti-His6–BPS IgG.

Parallel immunolocalization also requires that the two IgG fractions have similar detection capacities. For dot blotting, decreasing quantities of the GST-fusion proteins were dotted on a membrane and immunostained. Both anti-His6–BPS and anti-His6–CHS detected their antigens down to 0.004 μg, indicating similar sensitivities (Figure 2B).

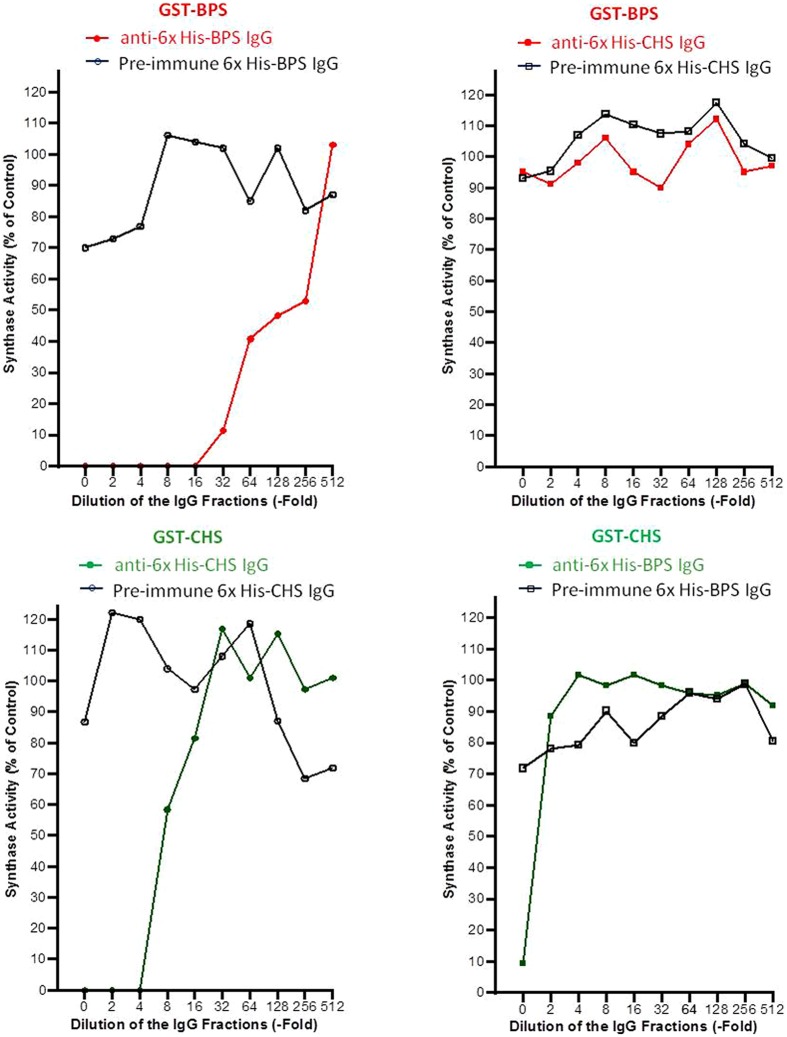

For immunotitration coupled with the determination of enzyme activity, first the stability of the PKSs was studied. BPS and CHS lost approx. 20 and 55%, respectively, of their activities within a day, however, the residual activities were sufficient for carrying out immunotitration. Constant quantities of the GST fusion proteins (2 μg) were mixed with decreasing quantities (1:2 to 1:512 dilutions) of the pre-immune and His6–IgG fractions. The PKS activities that remained in the supernatants of the titration mixtures were determined (Figure 3). Anti-His6–CHS IgG precipitated GST–CHS and did not crossreact with GST–BPS. Anti-His6–BPS IgG precipitated GST–BPS and exhibited, when undiluted, crossreactivity with GST–CHS. However, the undiluted IgG fractions were not used for immunolocalization. Pre-immune His6–CHS IgG did not recognize the PKSs, whereas pre-immune His6–BPS IgG resulted in weak precipitation of the proteins.

FIGURE 3.

The specific recognition of the antigens was confirmed by immunotitration. GST–BPS and GST–CHS were used as antigens in constant quantities (2 μg). Decreasing amounts of the anti-His6 and pre-immune IgG fractions (1:2–1:512 dilutions) were added. The BPS and CHS activities that were not precipitated and remained in the supernatants of the titration mixtures were determined.

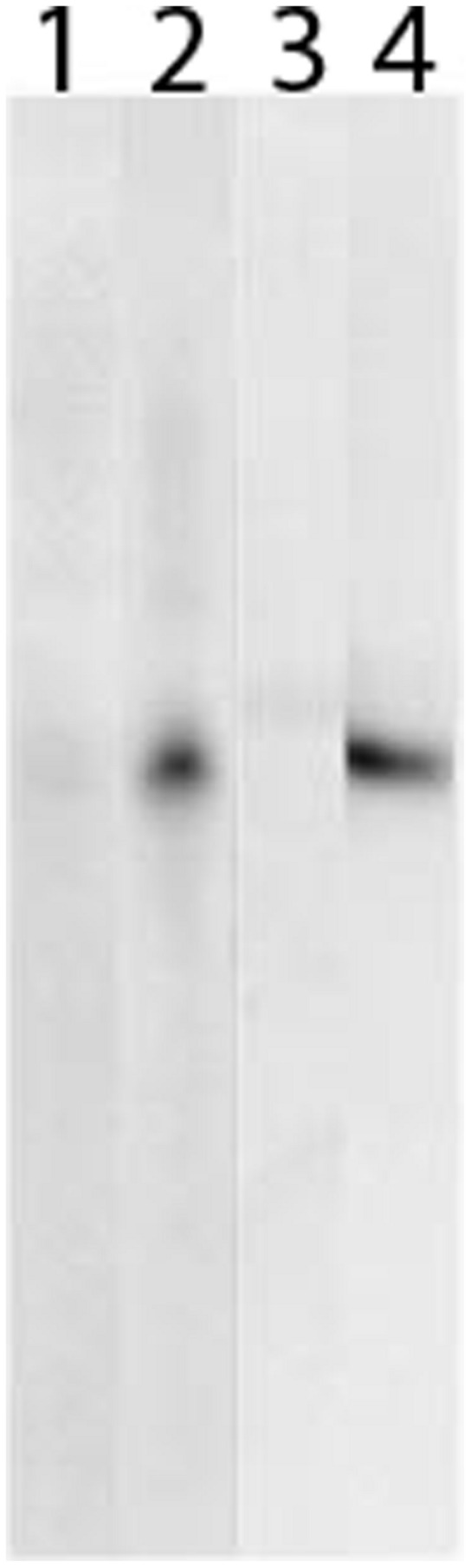

Antibody Monospecificity in Leaf Extract

For use in immunolocalization, the BPS and CHS antibodies must (i) not crossreact with each other and (ii) not crossreact with foreign proteins, which occur in the leaf. Therefore, protein extracts from H. perforatum leaves at different developmental stages were subjected to SDS–PAGE and subsequent immunoblotting (Figure 4). Both anti-His6–BPS IgG and anti-His6–CHS IgG detected a single protein band at approx. 43 kDa, which corresponds to the subunit molecular mass of BPS and CHS. Thus, monospecificity in leaf protein extract was demonstrated for both IgG fractions. No staining of protein bands was observed when the two pre-immue IgG fractions were used.

FIGURE 4.

Both BPS and CHS antibodies reacted monospecifically in leaf protein extract. Leaf proteins were separated by SDS–PAGE, blotted on a PVDF membrane and incubated with BPS pre-immune IgG (1), anti-His6–BPS IgG (2), CHS pre-immune IgG (3) and anti-His6–CHS IgG (4).

Immunolocalization of BPS and CHS to the Mesophyll

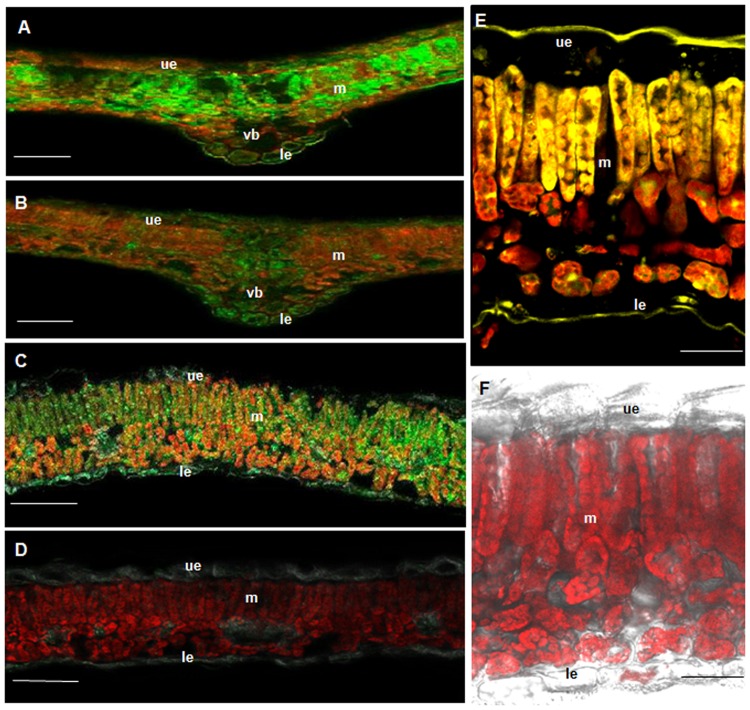

Localization by immunofluorescence was carried out with leaves of field-grown plants, using green fluorescent labeling (Alexa Fluor 488) and laser scanning confocal microscopy. Two alternative procedures of section preparation were examined, the resin (Technovit) and the cryo-sectioning techniques. Since resin-embedded sections exhibited strongly decreased PKS antigenicities and strong unspecific background labeling, cryo-sectioning was preferred. Best results, i.e., high level of specific detection and low level of background staining, were obtained with 1:25 dilutions of the IgG fractions. In addition, this dilution failed to cause any crossreactivity between the BPS and CHS IgG preparations, as described above.

For CHS, bright immunofluorescence was observed in the mesophyll (Figure 5A). Palisade and sponge cells exhibited similar staining intensities. The lambda signature of the Alexa Fluor 488-labeled sections verified the correct emission wavelength (520 nm). Epidermal tissue was devoid of immunostaining. No labeling was observed in control sections incubated with pre-immune IgG (Figure 5B).

FIGURE 5.

BPS and CHS as well as flavonoids are located in the mesophyll. Immunofluorescence localization of CHS (A,B) and BPS (C,D) using a green fluorescent dye. (A,C) Cross-sections incubated with anti-His6–CHS IgG and anti-His6–BPS IgG, respectively. (B,D) Cross-sections incubated with the pre-immune IgGs. Localization of flavonoids (E,F) using histochemical detection. (E) Staining of flavonoids with diphenylboric acid 2-aminoethyl ester (DPBA). (F) Control section exhibiting only the red autofluorescence of chlorophyll. ue, upper epidermis; le, lower epidermis; m, mesophyll; vb, vascular bundle. Bar, 100 μm (A–D), 20 μm (E,F).

BPS was also present in the mesophyll, however, the intensity of immunofluorescence was markedly lower than for CHS (Figure 5C). The upper and the lower epidermis were devoid of staining. No labeling was observed with pre-immune IgG (Figure 5D).

Histochemical Localization of Flavonoids to the Mesophyll

To stain the CHS products in H. perforatum leaf cross-sections, diphenylboric acid 2-aminoethyl ester (DPBA) was used (Figure 5E). Flavonoids were present in the mesophyll, palisade cells exhibiting stronger staining than sponge cells. The epidermal layers were devoid of labeling. No staining was observed in control sections (Figure 5F). For histochemical localization of xanthones, no specific stain was available.

Distinct Developmental Regulation of BPS and CHS

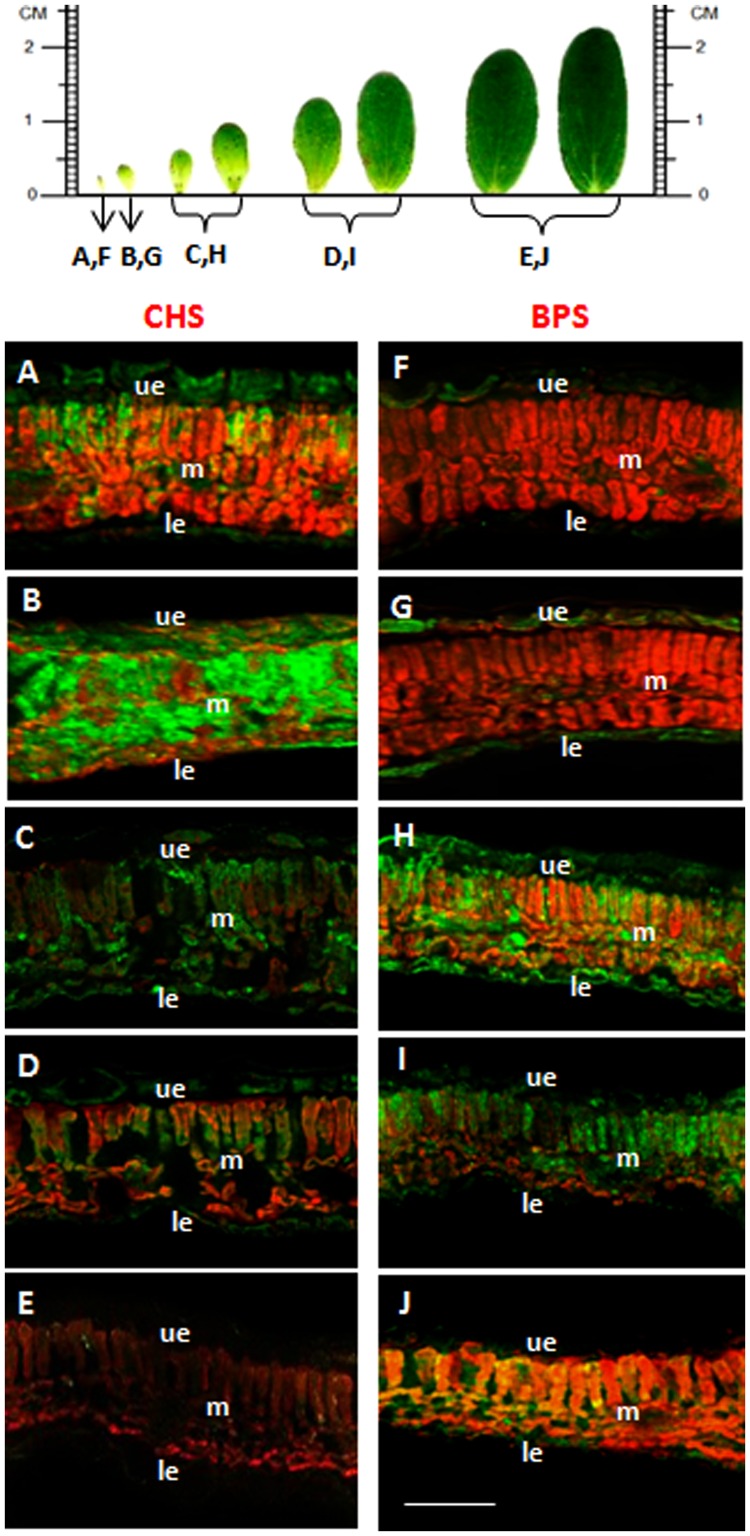

Leaves at various developmental stages were cross-sectioned and incubated with anti-His6–BPS IgG and anti–His6-CHS IgG in different sets of experiments. The intensity of immunofluorescence in the mesophyll changed with leaf age, which held true for both CHS and BPS (Figure 6). Maximum immunolabeling of CHS was observed in approx. 0.5 cm long leaves, which lacked detectable BPS quantities. The CHS-specific fluorescence rapidly decreased to a basal level in approx. 1 cm long leaves which, however, exhibited a high level of BPS immunofluorescence. In elder leaves, BPS fluorescence declined.

FIGURE 6.

The developmental stages of maximum BPS and CHS levels differ. CHS (A–E) and BPS (F–J) were immunolocalized using a green fluorescent dye. Sections were prepared from leaves with a blade length of approximately 0.3 cm (A,F), 0.5 cm (B,G), 0.8 cm (C,H), 1.5 cm (D,I) and 2.0 cm (E,J). ue, upper epidermis; le, lower epidermis; m, mesophyll. Bar, 100 μm.

Discussion

In the medicinal plant H. perforatum, the major active metabolites are formed by polyketide synthases, two of which are BPS and CHS. Demonstrated herein is that both BPS and CHS are located in H. perforatum leaves in the mesophyll tissue. Given the comparable detection capacities of the antibodies used, the immunofluorescence intensities for BPS and CHS differed significantly. The CHS level markedly exceeded the BPS level, which is in accordance with the previously detected quantities of flavonoids as CHS products and xanthones as BPS products. The flavonoid content in the aerial parts was 2–4%, the major compounds being quercetin derivatives, such as hyperoside and rutin (Nahrstedt and Butterweck, 1997; Hölzl and Petersen, 2003). In contrast, only traces of xanthones, such as 1,3,6,7-tetrahydroxyxanthone and mangiferin, were detected. As an exception, the aerial parts of Indian H. perforatum contained 2–4% xanthones (Muruganandam et al., 2000). Commonly, xanthones are abundant in roots of Hypericum species, which is consistent with the high BPS transcript level found in H. sampsonii roots (Pasqua et al., 2003; Huang et al., 2012; Zubrická et al., 2015). Therefore, immunohistochemical studies of these organs will be interesting.

CHS and BPS accumulated at different stages of leaf development, with CHS accumulation occurring earlier than that of BPS. Consistently, relatively high BPS transcript levels were detected in older leaves of H. sampsonii, whereas younger leaves had relatively high CHS transcript levels (Huang et al., 2012). Expression of CHS in young leaves is physiologically explainable. Due to absorption at 280–315 nm, flavonoids efficiently protect photosynthetically active tissue from damaging UV-B radiation, which can penetrate the ozone layer in the stratosphere (Harborne and Williams, 2000). Flavonoids also function as a preformed barrier against herbivore attack (Winkel-Shirley, 2001). As a consequence, flavonoid accumulation has to be initiated at an early stage of leaf development. In contrast, xanthones in Hypericum species serve as inducible defense compounds against microbial pathogens, i.e., phytoalexins (Abd El-Mawla et al., 2001; Franklin et al., 2009). Cell cultures of H. perforatum accumulated xanthones in response to the addition of a fungal elicitor prepared from Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, the causal agent of St. John’s wort wilt (Gärber and Schenk, 2003; Conceição et al., 2006). Furthermore, H. androsaemum and H. calycinum cell cultures accumulated prenylated xanthones upon challenge with elicitors and a cDNA encoding the prenyltransferase involved was isolated (Abd El-Mawla et al., 2001; Gaid et al., 2012; Fiesel et al., 2015).

In H. perforatum leaves, the CHS products were located in the mesophyll tissue, as indicated by histochemical staining. Thus, the sites of biosynthesis and storage of flavonoids are identical. No transport process takes place at the tissue level. Previously, a similar tissue distribution of flavonoid biosynthetic enzymes was observed in primary leaves of oat (Avena sativa) by peeling the epidermal layers (Knogge and Weissenböck, 1986). The entire pathway, including CHS, chalcone–flavanone isomerase and methyl- and glycosyltransferase activities, was located in the leaf mesophyll. However, flavonoids, in this case flavones, were found in both epidermis and mesophyll tissues, with up to 70% being detected in the two epidermal layers (Weissenböck and Sachs, 1977). Therefore, intercellular translocation of individual products was proposed. While vitexin derivatives are transported to the epidermis, isovitexin derivatives remain in the mesophyll. Alternatively, the epidermal product pattern may reflect flavonoid biosynthesis in the subepidermal mesophyll cells.

Strict compartmentation of flavonoids between tissues and a close correlation between leaf development and flavonoid metabolism were also observed in primary leaves of rye (Secale cereale; Schulz et al., 1985; Schulz and Weissenböck, 1986; Hutzler et al., 1998). While two C-glucosylapigenin-O-glycosides were accumulated in the two epidermal layers, two anthocyanins and two luteolin O-glucuronides were exclusively located in the mesophyll, as shown by isolation and separation of epidermal and mesophyll protoplasts. Maximum product accumulation coincided with maximum activities of selected flavonoid biosynthetic enzymes, such as glucuronosyltransferases (Schulz and Weissenböck, 1988).

A different tissue distribution of CHS and flavonoids than in primary leaves of grass seedlings was found in leaves of spinach (Spinacia oleracea), pea (Pisum sativum), and bean (Vicia faba), using immunofluorescence localization (Beerhues and Wiermann, 1988; Beerhues et al., 1988). CHS was present in the upper and the lower epidermis and to a minor extent in the subepidermal layers at an early developmental stage. CHS in leaves of spinach, pea and bean was restricted to the epidermal tissue and flavonoids were either exclusively or predominantly present in the epidermal layers, indicating that the sites of biosynthesis and storage were identical (Tissut and Ravanel, 1980; Hrazdina et al., 1982; Weissenböck et al., 1984, 1986). This was also true for parsley (Petroselinum crispum) leaves (Jahnen and Hahlbrock, 1988; Schmelzer et al., 1988). Using in situ hybridization, immunohistochemistry, and microspectrophotometry, light-induced CHS mRNA, CHS protein, and flavonoid products, respectively, were localized to epidermal cells, which thus contained the entire sequence of product formation. In leaves of Catharanthus roseus, CHS transripts and flavonoids were also co-localized by in situ hybridization and histochemistry to the epidermis, mainly the adaxial layer (Mahroug et al., 2006). Furthermore, epidermal tissue of needles of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) contained both CHS mRNA and products (Schnitzler et al., 1996).

For localization of xanthones, no specific staining was available and, even if, the low xanthone level was likely to be below the detection limit. In vitro regenerated shoots of H. perforatum even lacked detectable quantities of xanthones (Pasqua et al., 2003). An interesting alternative for xanthone localization may be leaves of Indian H. perforatum, which contain a high level of 1,3,5-trihydroxyxanthone derivatives (Muruganandam et al., 2000).

Author Contributions

AB, MG, BL, RH, and LB designed the research and analyzed data; AB carried out the immunochemical studies; MG performed the histochemical analysis; MG and LB prepared the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG). AB thanks the Libyan government for a Ph.D. scholarship.

References

- Abd El-Mawla A. M. A., Schmidt W., Beerhues L. (2001). Cinnamic acid is a precursor of benzoic acids in cell cultures of Hypericum androsaemum L. but not in cell cultures of Centaurium erythraea RAFN. Planta 212 288–293. 10.1007/s004250000394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Rahman I. A., Beuerle T., Ernst L., Abdel-Baky A. M., Desoky Eel D., Ahmed A. S., et al. (2013). In vitro formation of the anthranoid scaffold by cell-free extracts from yeast-extract-treated Cassia bicapsularis cell cultures. Phytochemistry 88 15–24. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2013.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abe I., Oguro S., Utsumi Y., Sano Y., Noguchi H. (2005). Engineered biosynthesis of plant polyketides: chain length control in an octaketide-producing plant type III polyketide synthase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127 12709–12716. 10.1021/ja053945v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin M. B., Noel J. P. (2003). The chalcone synthase superfamily of type III polyketide synthases. Nat. Prod. Rep. 20 79–110. 10.1039/b100917f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beerhues L. (1996). Benzophenone synthase from cultured cells of Centaurium erythraea. FEBS Lett. 383 264–266. 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00265-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beerhues L. (2011). “Biosynthesis of the active Hypericum perforatum constituents,” in Medicinal and Aromatic Plant Science and Biotechnology 5 (Special Issue 1): Hypericum, ed. Cirak C. (Isleworth: Global Science Books; ), 70–77. [Google Scholar]

- Beerhues L., Robenek H., Wiermann R. (1988). Chalcone synthases from spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.) II. Immunofluorescence and immunogold localization. Planta 173 544–553. 10.1007/BF00958968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beerhues L., Wiermann R. (1988). Chalcone synthases from spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.) I. Purification, peptide patterns, and immunological properties of different forms. Planta 173 532–543. 10.1007/BF00958967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M. M. (1976). A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72 248–254. 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chizzali C., Gaid M. M., Belkheir A. K., Hänsch R., Richter K., Flachowsky H., et al. (2012). Differential expression of biphenyl synthase gene family members in fire blight-infected apple ‘Holsteiner Cox’. Plant Physiol. 158 864–875. 10.1104/pp.111.190918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conceição L. F. R., Ferreres F., Tavares R. M., Dias A. C. P. (2006). Induction of phenolic compounds in Hypericum perforatum L. cells by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides elicitation. Phytochemistry 67 149–155. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Awaad I., Bocola M., Beuerle T., Liu B., Beerhues L. (2016). Bifunctional CYP81AA proteins catalyse identical hydroxylations but alternative regioselective phenol couplings in plant xanthone biosynthesis. Nat. Commun. 7 11472 10.1038/ncomms11472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiesel T., Gaid M., Müller A., Bartels J., El-Awaad I., Beuerle T., et al. (2015). Molecular cloning and characterization of a xanthone prenyltransferase from Hypericum calycinum cell cultures. Molecules 20 15616–15630. 10.3390/molecules200915616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin G., Conceição L. F. R., Kombrink E., Dias A. C. P. (2009). Xanthone biosynthesis in Hypericum perforatum cells provides antioxidant and antimicrobial protection upon biotic stress. Phytochemistry 70 60–68. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2008.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaid M. M., Sircar D., Müller A., Beuerle T., Liu B., Ernst L., et al. (2012). Cinnamate:CoA ligase initiates the biosynthesis of a benzoate-derived xanthone phytoalexin in Hypericum calycinum cell cultures. Plant Physiol. 160 1267–1280 10.1104/pp.112.204180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gärber U., Schenk R. (2003). Colletotrichum-wilt of St. John’s wort – Overview of results of examinations of several years. Drogenreport 16 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Görlach J., Schmid J. (1996). Introducing StuI sites improves vectors for the expression of fusion proteins with factor Xa cleavage sites. Gene 170 145–146. 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00825-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harborne J. B., Williams C. A. (2000). Advances in flavonoid research since 1992. Phytochemistry 55 481–504. 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)00235-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hölzl J., Petersen M. (2003). “Chemical constituents of Hypericum ssp,” in Hypericum – The Genus Hypericum, ed. Ernst E. (London: Taylor & Francis; ), 77–93. [Google Scholar]

- Hrazdina G., Marx G. A., Hoch H. C. (1982). Distribution of secondary plant metabolites and their biosynthetic enzymes in pea (Pisum sativum L.) leaves. Plant Physiol. 70 745–748. 10.1104/pp.70.3.745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L., Wang H., Ye H., Du Z., Zhang Y., Beerhues L., et al. (2012). Differential expression of benzophenone synthase and chalcone synthase in Hypericum sampsonii. Nat. Prod. Commun. 7 1615–1618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutzler P., Fischbach R., Heller W., Jungblut T. P., Reuber S., Schmitz R., et al. (1998). Tissue localization of phenolic compounds in plants by confocal laser scanning microscopy. J. Exp. Bot. 49 953–965. 10.1093/jxb/49.323.953 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jahnen W., Hahlbrock K. (1988). Differential regulation and tissue-specific distribution of enzymes of phenylpropanoid pathways in developing parsley seedlings. Planta 173 453–458. 10.1007/BF00958957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karppinen K., Hokkanen J., Mattila S., Neubauer P., Hohtola A. (2008). Octaketide-producing type III polyketide synthase from Hypericum perforatum is expressed in dark glands accumulating hypericins. FEBS J. 275 4329–4342. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06576.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klundt T., Bocola M., Lütge M., Beuerle T., Liu B., Beerhues L. (2009). A single amino acid substitution converts benzophenone synthase into phenylpyrone synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 284 30957–30964. 10.1074/jbc.M109.038927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knogge W., Weissenböck G. (1986). Tissue-distribution of secondary phenolic biosynthesis in developing primary leaves of Avena sativa L. Planta 167 196–205. 10.1007/BF00391415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linde K., Berner M. M., Kriston L. (2008). St John’s wort for major depression. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 4:CD000448 10.1002/14651858.CD000448.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B., Falkenstein-Paul H., Schmidt W., Beerhues L. (2003). Benzophenone synthase and chalcone synthase from Hypericum androsaemum cell cultures: cDNA cloning, functional expression, and site-directed mutagenesis of two polyketide synthases. Plant J. 34 847–855. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01771.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B., Raeth T., Beuerle T., Beerhues L. (2007). Biphenyl synthase, a novel type III polyketide synthase. Planta 225 1495–1503. 10.1007/s00425-006-0435-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahroug S., Courdavault V., Thiersault M., St-Pierre B., Burlat V. (2006). Epidermis is a pivotal site of at least four secondary metabolic pathways in Catharanthus roseus aerial organs. Planta 223 1191–1200. 10.1007/s00425-005-0167-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuuchi Y., Shi S. P., Wanibuchi K., Kojima A., Morita H., Noguchi H., et al. (2009). Novel type III polyketide synthases from Aloe arborescens. FEBS J. 276 2391–2401. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.06971.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll S., Anke S., Kahmann U., Hänsch R., Hartmann T., Ober D. (2002). Cell-specific expression of homospermidine synthase, the entry enzyme of the pyrrolizidine alkaloid pathway in Senecio vernalis, in comparison with its ancestor, deoxyhypusine synthase. Plant Physiol. 130 47–57. 10.1104/pp.004259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muruganandam A. V., Ghosal S., Bhattacharya S. K. (2000). The role of xanthones in the antidepressant activity of Hypericum perforatum involving dopaminergic and serotoninergic systems. Biog. Amines 15 553–567. [Google Scholar]

- Nahrstedt A., Butterweck V. (1997). Biologically active and other chemical constituents of the herb of Hypericum perforatum. Pharmacopsychiatry 30(Suppl.), 129–134. 10.1055/s-2007-979533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nualkaew N., Morita H., Shimokawa Y., Kinjo K., Kushiro T., De-Eknamkul W., et al. (2012). Benzophenone synthase from Garcinia mangostana L. pericarps. Phytochemistry 77 60–69. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2012.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasqua G., Avato P., Monacelli B., Santamaria A. R., Argentieri M. P. (2003). Metabolites in cell suspension cultures, calli, and in vitro regenerated organs of Hypericum perforatum cv. Topas. Plant Sci. 165 977–982. 10.1016/S0168-9452(03)00275-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmelzer E., Jahnen W., Hahlbrock K. (1988). In situ localization of light-induced chalcone synthase mRNA, chalcone synthase, and flavonoid end products in epidermal cells of parsley leaves. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85 2989–2993. 10.1073/pnas.85.9.2989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnitzler J. P., Jungblut T. P., Heller W., Köfferlein M., Hutzler P., Heinzmann U., et al. (1996). Tissue localization of UV-B-screening pigments and of chalcone synthase mRNA in needles of scots pine seedlings. New Phytol. 132 247–258. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1996.tb01844.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz M., Strack D., Weissenböck G., Markham K. R., Dellamonica G., Chopins J. (1985). Two luteolin O-glucuronides from primary leaves of Secale cereale. Phytochemistry 24 343–345. 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)83549-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz M., Weissenböck G. (1986). Isolation and separation of epidermal and mesophyll protoplasts from rye primary leaves – tissue-specific characteristics of secondary phenolic product accumulation. Z. Naturforsch. 41c, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz M., Weissenböck G. (1988). Dynamics of the tissue-specific metabolism of luteolin glucuronides in the mesophyll of rye primary leaves (Secale cereale). Z. Naturforsch. 43c, 187–193. [Google Scholar]

- Tissut M., Ravanel P. (1980). Repartition des flavonols dans l’epaisseur des feuilles de quelques vegetaux vasculaires. Phytochemistry 19 2077–2081. 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)82197-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weissenböck G., Hedrich R., Sachs G. (1986). Secondary phenolic products in isolated guard cell, epidermal cell and mesophyll cell protoplasts from pea (Pisum sativum L.) leaves: distribution and determination. Protoplasma 134 141–148. 10.1007/BF01275712 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weissenböck G., Sachs G. (1977). On the localization of enzymes related to flavonoid metabolism in sections and tissues of oat primary leaves. Planta 137 49–52. 10.1007/BF00394434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissenböck G., Schnabl H., Sachs G., Elbert C., Heller F. O. (1984). Flavonol content of guard cell and mesophyll cell protoplasts isolated from Vicia faba leaves. Physiol. Plant. 62 356–362. 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1984.tb04586.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Winkel-Shirley B. (2001). Flavonoid biosynthesis. A colorful model for genetics, biochemistry, cell biology, and biotechnology. Plant Physiol. 126 485–493. 10.1104/pp.126.2.485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wölfle U., Seelinger G., Schempp C. M. (2014). Topical application of St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum). Planta Med. 80 109–120. 10.1055/s-0033-1351019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubrická D., Mišianiková A., Henzelyová J., Valletta A., De Angelis G., D’Auria F. D., et al. (2015). Xanthones from roots, hairy roots and cell suspension cultures of selected Hypericum species and their antifungal activity against Candida albicans. Plant Cell Rep. 34 1953–1962. 10.1007/s00299-015-1842-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]