Abstract

Fungal infections of the nose and paranasal sinuses can be categorized into invasive and non-invasive forms. The clinical presentation and course of the disease is primarily determined by the immune status of the host and can range from harmless or subtle presentations to life threatening complications. Invasive fungal infections are categorized into acute, chronic or chronic granulomatous entities. Immunocompromised patients with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, HIV and patients receiving chemotherapy or chronic oral corticosteroids are mostly affected. Mycetoma and Allergic Fungal Rhinosinusitis are considered non-invasive forms. Computer tomography is the gold-standard in sinonasal imaging and is complimented by Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as it is superior in the evaluation of intraorbital and intracranial extensions. The knowledge and identification of the characteristic imaging patterns in invasive – and non- invasive fungal rhinosinusitis is crucial and the radiologist plays an important role in refining the diagnosis to prevent a possible fatal outcome.

Keywords: Complications, fungal infections, invasive, magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography, non-invasive, sinonasal

Jose Gavito-Higuera

INTRODUCTION

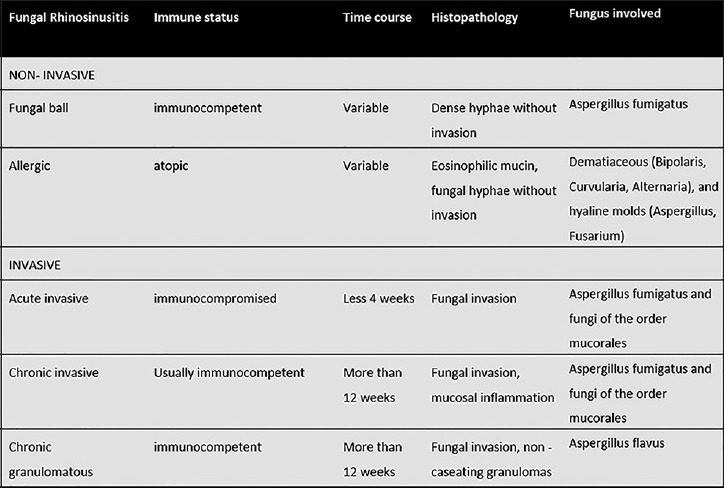

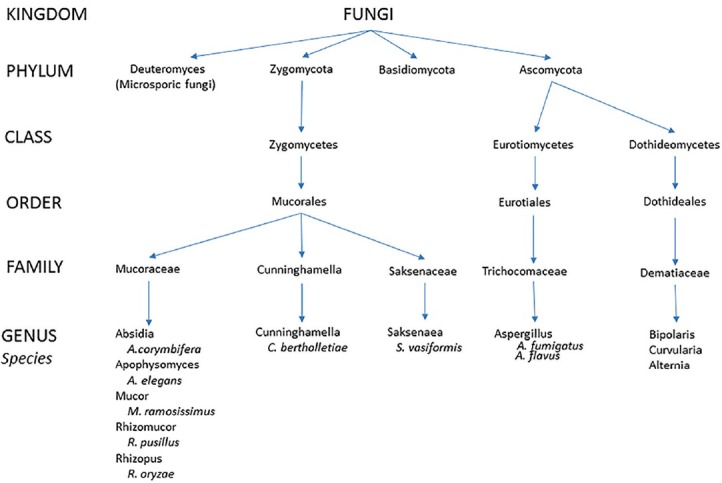

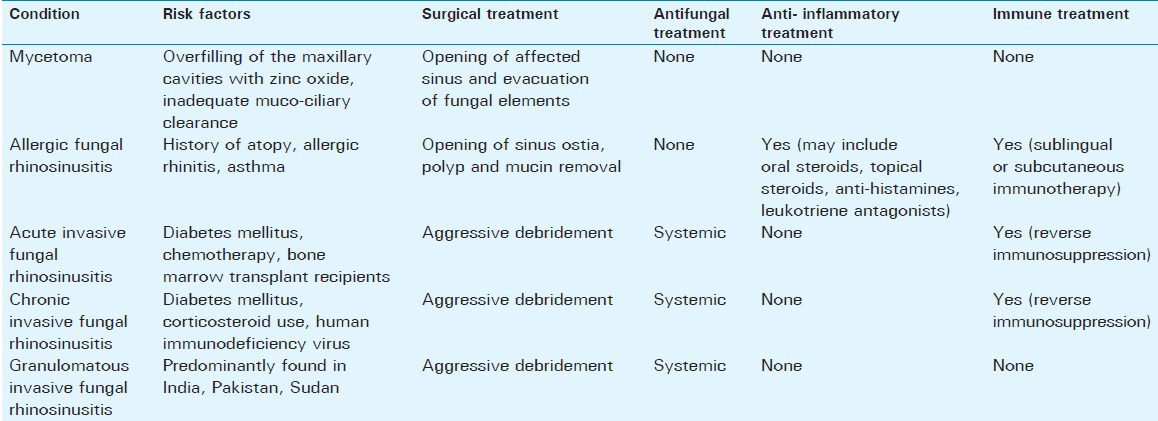

Fungi are ubiquitous in nature, and human exposure to fungi is unavoidable. The extent of fungal infections of the nose and paranasal sinuses is, therefore, primarily determined by the immune status of the host rather than the presence or absence of fungal organisms and can range from saprophytic colonization to orbital and cerebral involvement with often fatal outcomes. Due to a growing number of chemotherapy, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections, and diabetes mellitus, the number of susceptible immunocompromised hosts is increasing. Sinonasal fungal infections can be broadly divided into invasive and noninvasive forms. Invasive fungal sinusitis is defined by the presence of fungal hyphae within the mucosa, submucosa, bone, or blood vessels of the paranasal sinuses, differentiating it from noninvasive forms.[1,2] Depending on the immunologic response of the host and the course of the disease, invasive fungal sinusitis can be categorized into acute, chronic, or chronic granulomatous entities. Mycetoma and allergic fungal rhinosinusitis are considered noninvasive forms. Figure 1 summarizes the forms and characteristics of fungal rhinosinusitis and [Figure 2] gives an overview of organisms involved in sinonasal and orbital fungal infections.[3] Risk factors for the development of fungal rhinosinusitis and treatment options are summarized in Table 1.[1]

Figure 1.

Forms and characteristics of fungal rhinosinusitis.

Figure 2.

Phylogenic tree of organisms causing sinonasal and orbital fungal infections (modified after Kirszrot and Rubin).

Table 1.

Summary of the risk factors and treatment options of fungal rhinosinusitis (modified after Soler, Sc., Schlosser)

Computer tomography (CT) is the gold standard in paranasal sinus imaging and is complemented by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as it is superior in the evaluation of intracranial and intraorbital extensions.[2,4]

NONINVASIVE FUNGAL SINUSITIS: MYCETOMA (FUNGUS BALL)

A mycetoma is a noninvasive, dense conglomeration of fungal hyphae within a sinus cavity secondary to a deficient mucociliary clearance mechanism.[2] It is primarily caused by Aspergillus fumigatus, resulting in chronic rhinosinusitis predominantly involving the maxillary sinus (84%) and it is often found in older immunocompetent females.[1,3,5]

On noncontrast CT imaging, a mycetoma appears as a hyperattenuating mass with intralesional metal-dense spots corresponding to fungal waste products and it is often accompanied by perilesional reactive osteitis. On T1- and T2-weighted imaging (WI), a fungal ball appears hypointense due to the absence of water and with an hyperintense-inflamed mucosal lining on T2-WI [Figure 3].[2]

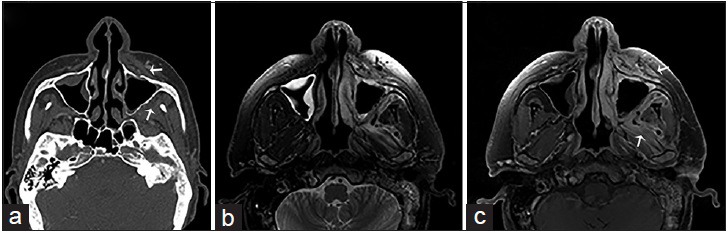

Figure 3.

A 65-year-old female, who presented with a history of chronic sinusitis, headaches, and facial discomfort, is diagnosed with a mycetoma. Contrast computer tomography scan of the face in axial view in (a) soft tissue and (b) bone algorithm show complete opacification of the right maxillary sinus with intralesional calcification (arrows) and reactive osteitis, indicative of chronic sinusitis. (c) Corresponding T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of the face in axial view shows a low attenuating mass in the right maxillary sinus with surrounding mucosal thickening, consistent with a mycetoma (asterisk).

ALLERGIC FUNGAL SINUSITIS

Allergic fungal sinusitis is an IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reaction to fungal elements and the most common form of fungal sinusitis.[1,4] Disease tends to be bilateral and asymmetric involving multiple sinuses with a frequent nasal component.[1,2] Patients typically have an intact immune system and a history of atopy, including allergic rhinitis or asthma and can present with proptosis, telecanthus, or gross facial dysmorphia.[1] Causative agents include dematiaceous (Bipolaris, Curvularia, and Alternaria) and hyaline molds (Aspergillus and Fusarium).[1,3,4,5]

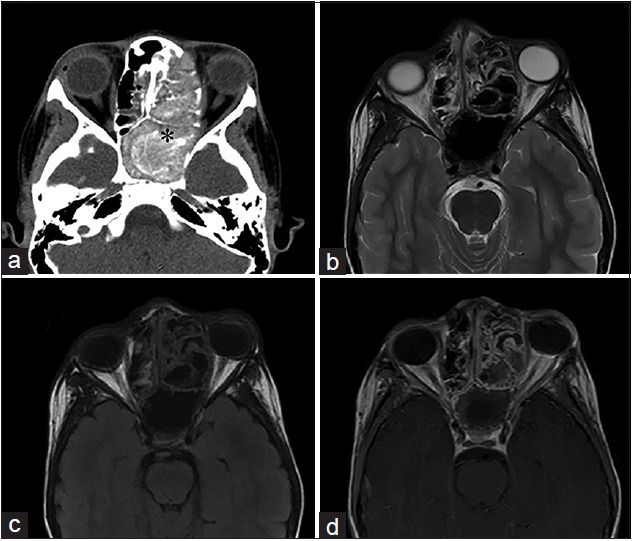

On CT imaging, the paranasal sinuses appear enlarged with near-complete opacification due to mucin accumulation, which appears hyperdense on noncontrast CT imaging.[2,6] MRI T1-WIs show mixed signal intensities of the allergic mucin and characteristic signal voids on T2-WI, which are attributed to its high concentration of metal ions, proteins, and low free-water content.[1,2,6] The overlying inflamed mucosal lining appears relatively hypointense on T1-WI and hyperintense on T2-WI, with increased signal intensity upon administration of intravenous gadolinium [Figure 4].[2] As the quantity of fungal mucin increases, the involved paranasal sinuses begin to resemble a mucocele and bony remodeling, and decalcification may occur with subsequent nasal, intraorbital, or intracranial involvement mimicking malignancy.

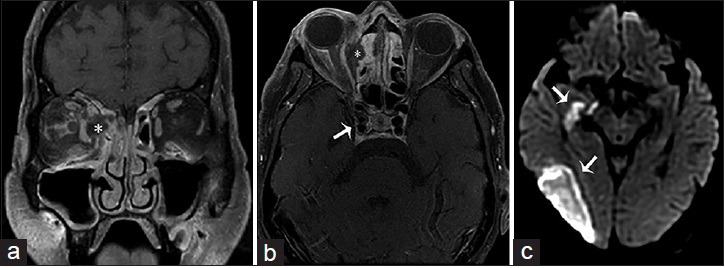

Figure 4.

An 11-year-old male, who presented with rhinorrhea and a 2-month history of “left eye swelling,” is diagnosed with allergic fungal sinusitis (Curvularia Sp). (a) Noncontrast computed tomography of the head in axial view shows opacification of the left ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses, with internal hyperattenuating material and expansion and remodeling of the involved sinuses (asterisk). (b) T2-weighted and (c) T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of the face in axial view demonstrates the low signal intensity of the mucin due to high concentrations of various metals metabolized by the fungus and a high protein and low free water content. (d) Corresponding T1-weighted postgadolinium magnetic resonance imaging of the face in axial view demonstrates a hyperintense inflamed mucosal lining. No enhancement of the sinus cavity or its contents allows a differentiation from neoplastic entities.

INVASIVE FUNGAL SINUSITIS

Depending on the progression of the disease and the immune status of the host, invasive fungal sinusitis can be categorized into acute, chronic, or granulomatous subtypes. Causative agents most commonly identified are Aspergillus and fungi of the order Murocales (Zygomycetes). Their ability to angio-invade reflects in the presence of fungal hyphal forms within the mucosa, submucosa, blood vessels, and bone, often resulting in orbital and intracranial involvement.[4] Complications may include orbital and intracranial extensions with cavernous sinus thrombosis, parenchymal cerebritis or abscess, meningitis, osteomyelitis, mycotic aneurysm, stroke, and hematogenous dissemination.

Acute invasive fungal rhinosinusitis is found in an immunocompromised setting with a course of disease of 4 weeks or less.[6] Chronic invasive fungal rhinosinusitis shows a prolonged clinical development of over more than 12 weeks and it is found in immunocompetent or slightly immunocompromised patients.[5,6] Granulomatous-invasive fungal sinusitis is characterized by the presence of noncaseating granulomas in immunocompetent hosts and a course of disease of over 12 weeks.[7] Aspergillus flavus is mostly identified as the causative agent and infections are primarily found in Sudan, India, and Pakistan, with less prevalence in the United States.[7]

ACUTE INVASIVE FUNGAL RHINOSINUSITIS

Acute invasive fungal rhinosinusitis is the most urgent and lethal form of fungal sinusitis with a mortality of 50–80%.[2] Immunocompromised patients with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus and those receiving chemotherapy or chronic oral corticosteroids and patients with HIV are most commonly affected.[2,4,5] Aspergillus is the fungal species predominantly identified in patients with neutropenia and fungi of the Zygomycetes class are mostly encountered in diabetic patients.[2,8] Infection commonly begins as mucosal inflammation around the middle turbinate and rapidly spreads to the maxillary, ethmoid, or sphenoid sinus, usually affecting multiple unilateral sinuses.[9] Infectious spread to the adjacent soft tissue, and periantral fat planes, orbits, and central nervous system occur through direct extension or through vascular invasion owing to the angio-invasive nature of the fungi. Hyphal growth into the vessel lumen causes endothelial dysfunction and thrombosis.[8]

Orbital involvement is often characterized by periorbital edema, ptosis, ophthalmoplegia, visual loss, or proptosis. Altered mental status is concerned for spread to the central nervous system, which is at an increased risk if the posterior ethmoid or sphenoid cells are affected, and its involvement is associated with twice the mortality.[8,9]

Nonspecific findings on CT scan include mass effect, bony dehiscence, thickening of the extraocular muscles, and inflammatory changes of the orbit and orbital apex. Mucosal secretions may be hyper- or hypo-attenuating, although hyperattenuation is mostly attributed to chronic invasive fungal rhinosinusitis. MRI further evaluates the soft tissue extension beyond the sinuses to the periantral fat (intraorbital or masticator space), the cavernous sinus, and the brain and therefore, better demonstrates the findings of fulminant fungal invasion [Figures 5–7]. Biopsy remains crucial in the diagnosis of acute invasive fungal rhinosinusitis to isolate the fungus involved and initiate the appropriate treatment.

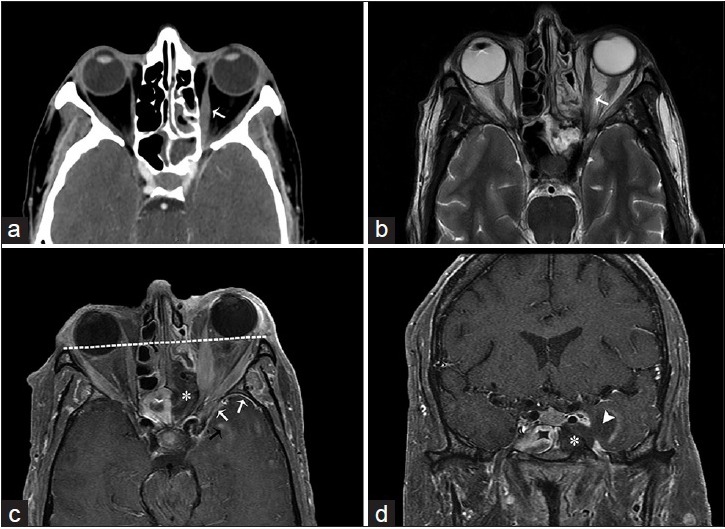

Figure 5.

A 44-year-old male, who presented with gradually increasing left jaw swelling and pain over the course of 2 weeks, is diagnosed with acute invasive zygomycosis. The patient had a history of hepatitis C and alcoholic liver cirrhosis. (a) Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan of the face in the bone algorithm, axial view shows mucosal thickening of the maxillary sinuses with the erosion of the left maxillary bone (anterior and posterior walls) and obliteration of the periantral fat planes in the premaxillary and masticator spaces (arrows). (b) Magnetic resonance imaging T2-weighted and (c) gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted fat saturated imaging of the face in axial view shows inflammatory changes and contrast enhancement in the described periantral planes and masticator muscles due to fungal invasion (arrows).

Figure 7.

A 63-year-old female, who presented with altered mental status, decreased vision and left-sided weakness of the face and arm, and a history of sinusitis and uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus, is diagnosed with rhino-orbital-cerebral-zygomycosis (mucormycosis). T1-weighted fat saturated postgadolinium images of the brain in (a) coronal and (b) axial view shows ethmoidal sinusitis with bone erosion and a subperiosteal abscess (asterisk) occupying the medial aspect of the right orbit and displacing the medial rectus muscle laterally and extension to the right cavernous sinus with internal carotid artery invasion (arrow in b). (c) Diffusion-weighted imaging demonstrates an acute infarct in the territory of the right middle cerebral artery (arrows).

Figure 6.

A 55-year-old male, who presented with headaches, rhinorrhea, vision loss, and acute myelogenous leukemia, is diagnosed with acute invasive aspergillosis. (a) Computed tomography scan with contrast and (b) T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of the face in axial view demonstrate inflammation of the left ethmoidal and sphenoid sinuses with thickening of the left medial rectus muscle due to intraorbital extension (arrows). T1-weighted fat saturated postgadolinium magnetic resonance imaging of the face in axial (c) and coronal (d) view shows absence of enhancement of the left posterior ethmoid and sphenoid sinus mucosa indicative of gangrenous necrosis (asterisk), intraorbital extension resulting in proptosis (line), intracranial extension through the partially thrombosed left cavernous sinus with abnormal leptomeningeal (black arrow) and pachymeningeal enhancement (white arrows), and abscess formation in the left temporal fossa (arrowhead).

CHRONIC INVASIVE FUNGAL RHINOSINUSITIS

Patients are usually immunocompetent or slightly immunocompromised due to corticosteroid therapy, diabetes mellitus, or AIDS.[5,2,6] The most common pathogens identified are those causing acute invasive fungal sinusitis as well as dematiaceous molds (Bipolaris, Curvularia, Alternaria, and Pseudoalleschia), affecting mostly the ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses.[1,5,6] Patients usually endure sinus pain, nasal discharge, low-grade fever, and epistaxis, and infection can be recurrent and persistent.

Imaging features are similar to acute invasive fungal rhinosinusitis, noninvasive forms, or a combination of both. On noncontrast CT imaging, a hyperattenuating mass with bony wall destruction extending into the adjacent structures such as the orbits, maxillary floor, and hard palate visualizes the chronic invasive course of the infection and may mimic malignancy.[2] MRI is more accurate for the evaluation of extension into the orbital apex, cavernous sinus, or brain [Figure 8].

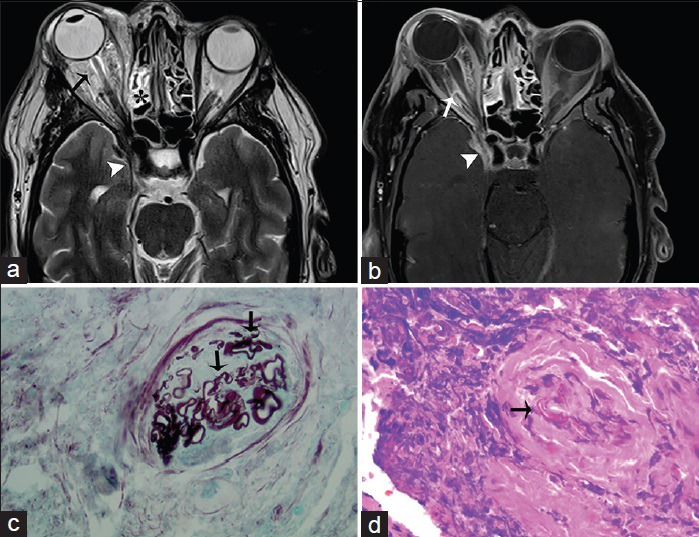

Figure 8.

A 41-year-old male, who presented with chronic sinusitis, decreased vision, swelling of the right eye, and numbness of the face, is diagnosed with mucormycosis. The patient had a history of poorly controlled diabetes mellitus. (a) Axial T2-weighted and (b) corresponding T1-weighted fat saturated postgadolinium magnetic resonance imaging of the head in axial view shows inflammatory thickening of the ethmoidal sinus (asterisk) with expansion and dehiscence of the right orbital wall and marked inflammatory changes of the orbital fat and extraocular muscles (arrows) indicative of ocular invasion and resulting in ipsilateral proptosis. Inflammatory changes are extending through the orbital apex and right cavernous sinus (arrowhead) (c) Gomori methenamine silver stain outlines mucorales fungal microorganisms (arrows) (d) high power view of the ethmoid tissue shows mucorales of fungal microorganisms (arrow) involving blood vessels (H and E).

CONCLUSION

Invasive and noninvasive sinonasal fungal infections are closely associated with the host's immune system and ability to generate a proper immune response. Depending on the immune status of the host, infections may present as harmless colonization or include noninvasive or invasive forms. Knowledge and identification of the characteristic imaging patterns found in invasive and noninvasive fungal rhinosinusitis allow the radiologists to help refine the diagnosis and guide clinicians in the further evaluation and initialization of a proper and timely treatment to help prevent a possibly fatal outcome.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.clinicalimagingscience.org/text.asp?2016/6/1/23/184010

REFERENCES

- 1.Soler ZM, Schlosser RJ. The role of fungi in diseases of the nose and sinuses. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2012;26:351–8. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2012.26.3807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aribandi M, McCoy VA, Bazan C., 3rd Imaging features of invasive and noninvasive fungal sinusitis: A review. Radiographics. 2007;27:1283–96. doi: 10.1148/rg.275065189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirszrot J, Rubin PA. Invasive fungal infections of the orbit. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2007;47:117–32. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0b013e31803776db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoxworth JM, Glastonbury CM. Orbital and intracranial complications of acute sinusitis. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2010;20:511–26. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thompson GR, 3rd, Patterson TF. Fungal disease of the nose and paranasal sinuses. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:321–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mossa-Basha M, Ilica AT, Maluf F, Karakoç Ö, Izbudak I, Aygün N. The many faces of fungal disease of the paranasal sinuses: CT and MRI findings. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2013;19:195–200. doi: 10.5152/dir.2012.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim TH, Jang HU, Jung YY, Kim JS. Granulomatous invasive fungal rhinosinusitis extending into the pterygopalatine fossa and orbital floor: A case report. Med Mycol Case Rep. 2012;1:107–11. doi: 10.1016/j.mmcr.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorovoy IR, Kazanjian M, Kersten RC, Kim HJ, Vagefi MR. Fungal rhinosinusitis and imaging modalities. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2012;26:419–26. doi: 10.1016/j.sjopt.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Middlebrooks EH, Frost CJ, De Jesus RO, Massini TC, Schmalfuss IM, Mancuso AA. Acute invasive fungal rhinosinusitis: A comprehensive update of CT findings and design of an effective diagnostic imaging model. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;36:1529–35. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]