Abstract

Objective:

The purpose of this study was to review the uses of electromyography (EMG) in dentistry in the last few years in related research. EMG is an advanced technique to record and evaluate muscle activity. In the previous days, EMG was only used for medical sciences, but now EMG playing a tremendous role in medical as well as dental sector.

Materials and Methods:

Several electronic databases such as Google Scholar, PubMed, Science Direct, and Web of Science were systematically searched for studies published until July 2015.

Results:

EMG can be used in both diagnosis and treatment purpose to record neuromuscular activity. In dentistry, we can utilize EMG to evaluate muscular activity in function such as chewing and biting or parafunctional activities such as clenching and bruxism. In case of TMJ and myofascial pain disorders, EMG widely is used in the last few years.

Conclusions:

EMG is one of biometric tests that occur in the modern evidence-based dentistry practice.

Keywords: Dental disease, dentistry, muscle function, myofascial pain disorder syndrome, parafunctional habits, surface electromyography

INTRODUCTION

Electromyography (EMG) is well-defined as the recording and study of the fundamental electrical properties of skeletal muscle using superficial or needle electrodes which basically determine the muscle is contracting or not. EMG is widely practiced both in clinical and research fields. In dentistry, uses of EMG is more common in temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorder, TMJ dysfunction, dystonia, muscle disease of head and neck, cranial nerve lesion, and also seizure disorders.[1] EMG is also used in finding of some more diseases which are associated with damage of muscle tissue and nerve as EMG performed in the tongue muscle due to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and facial muscle due to myasthenia gravis.[1] Moreover, EMG plays an important role in the diagnosis of facial muscle during orthodontic treatment related to neuromuscular approach and facial pain associated with the use of functional appliance.[1] There are two methods of EMG – surface EMG and intramuscular EMG recording.[2] Usually, surface EMG is used to assess muscle function by recording muscle activity from the surface over the muscle on the skin using a pair of electrodes.[2] Surface EMG permits the noninvasive investigation of the bioelectrical phenomena of muscular contraction.[1] This instrument EMG adequately allows the examination of some important muscles involved in chewing, swallowing, and posture of the head (typically masseter, temporalis anterior and posterior, digastric anterior, sternocleidomastoid).[2] On the other hand, intramuscular EMG can perform using different types of recording electrode.[2] Its simplest one is a monopolar needle electrode.[2] For identifying the nature and position of motor unit lesions via recording, the electrical activity is induced in muscle by electrical stimulation of its nerve.[2]

Here, we choose those articles which are related to EMG activity in the dental field. This review of meta-analysis will evaluate the quality of those studies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

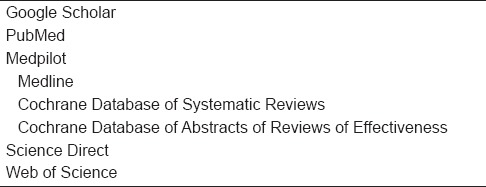

The main approach of this study was to search in five electronic databases [Table 1] where some keyword combinations were used to systematically search for those literature published until (including) April 2015.

Table 1.

Electronic databases searched

Here, the main concern was to find out the uses of EMG in dentistry. Data were fully collected for a purposive study. The inclusion criteria were identified as the papers using EMG in the dental sector, neck EMG records in the head and region, and also describe the importance of EMG activity in dental practices. On the other hand, the papers using EMG for medical purpose which was not related to dentistry definitely were excluded from the study. In exclusion criteria, it also added that those studies not done in human (like animal study) and the publications not in English.

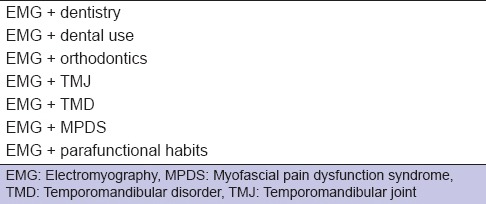

After this electronic database searching, the total amount of paper was founded and from that, we selected a number of papers based on inclusion and exclusion criteria [Table 2]. For analytic part, we select mean and standard deviation value of a number of papers, and meta-analysis was done for systemic review.

Table 2.

Keyword combination with which systematic literature search was conducted

RESULTS

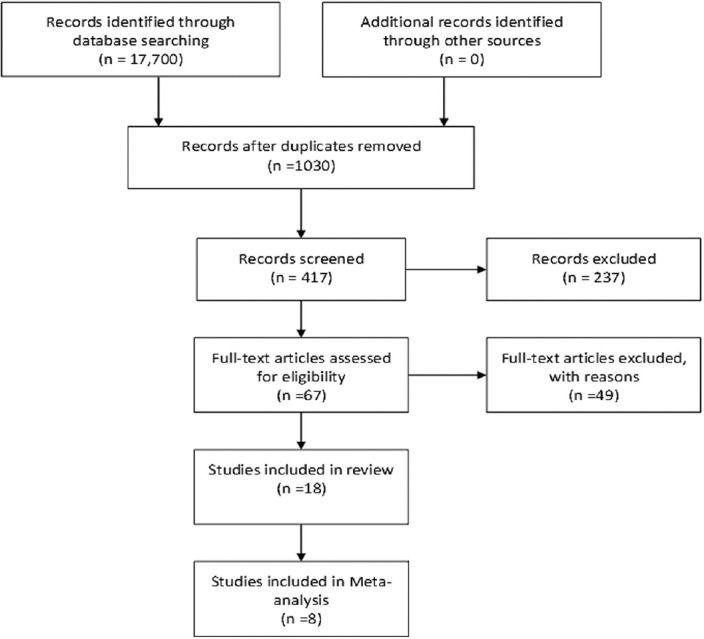

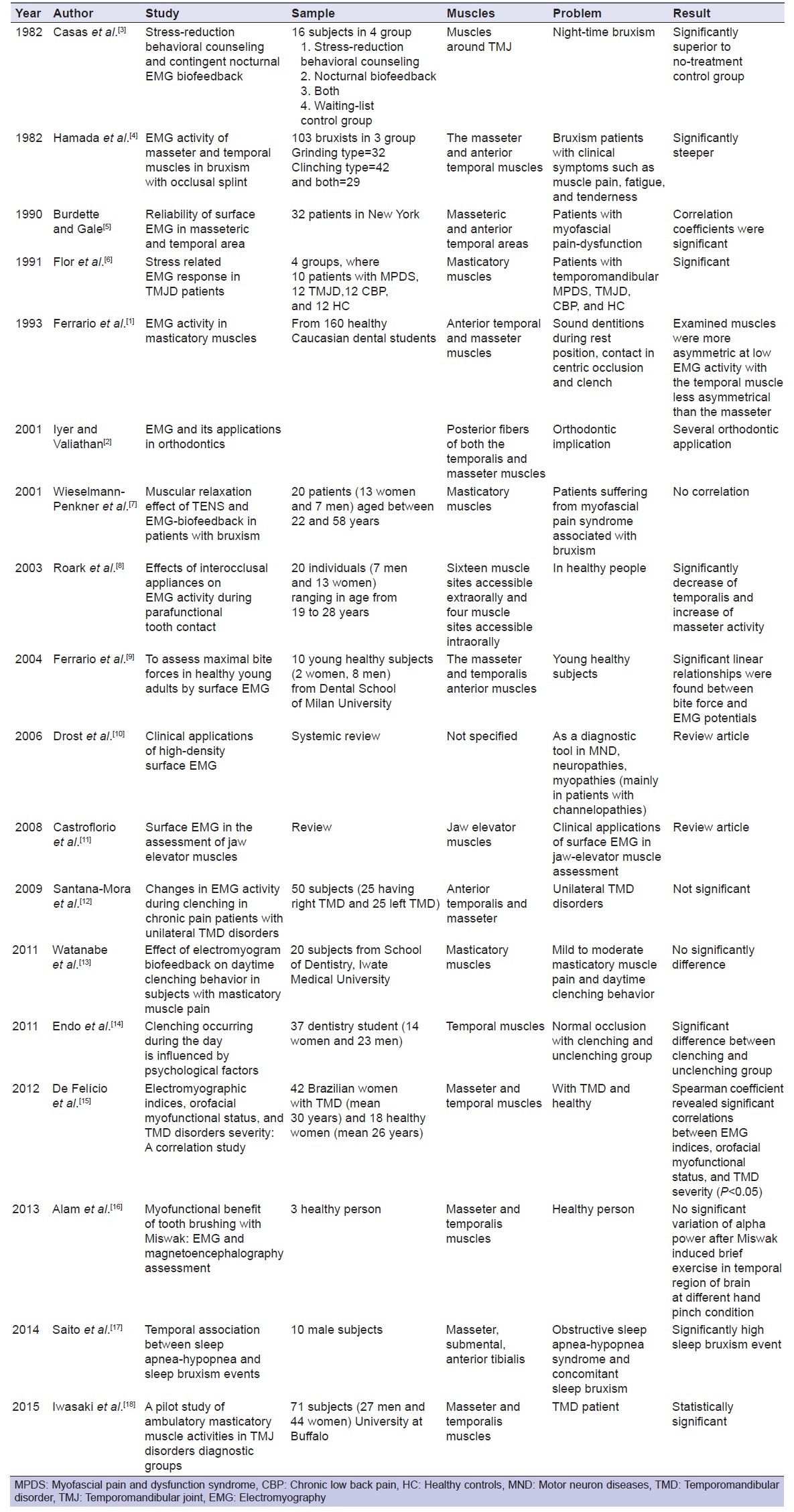

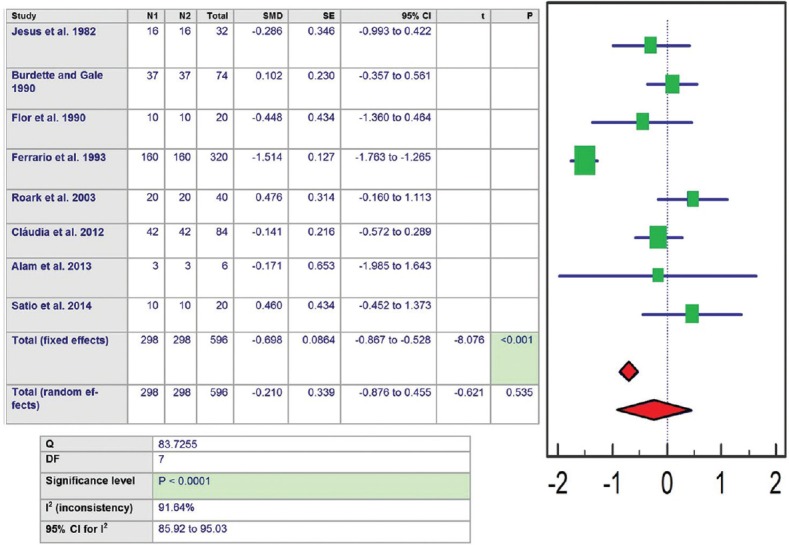

The studies that search in the different databases including their selection procedure have been mentioned in Figure 1. From total 17,700 hits, duplicates were removed, and 189 studies found after screening. Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 18 full-text articles were selected for this review. These studies well-arranged in Table 3 clearly reflect the results of individual study. Among them, only eight studies fulfilled the criteria of meta-analysis [Figure 2]. In meta-analysis, it showed P < 0.001 for fixed effect and 0.535 for random effects. After the forest plot, Q-test was 83.7255 and I2 value was 91.64%. Hence, it indicates the presence of considerable heterogeneity.

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing systematic literature search according to PRISMA guidelines

Table 3.

Electromyography use and study in dental sector

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of binary outcome measures in forest plot

DISCUSSION

EMG is a technique for assessment and record the electrical activity produced by muscles while they are resting or in function. It helps in diagnosis and analysis of optimal results by protecting hard and soft tissue, implants, and restorations. The bio-EMG is specifically designed to record craniofacial muscle activity in both resting conditions.[2] EMG has several uses in general dentistry within our practice, including orthodontics, implants, occlusion or bite correction, and TMJ disorder or sleep disorders.[1] In dentistry for the last few decades, EMG are used in several purposes such as assessing muscles of the head and neck at rest and in function.

In 1982, Hamada et al. conducted an electromyographic study of the masseter and anterior temporal muscle in bruxism patients with muscle pain, fatigue, and tenderness to find out an appropriate treatment option for such patients. In bruxism, causes of patients show fatigue existence of masticatory muscles due to hyperactivity.[4] Kishimoto in 1957 explained that canine teeth most often have shown response during teeth grinding, abnormal occlusal wear and also reported that anterior temporal muscle is more active in EMG.[19]

In 1984, Wood and Tobias conducted a study to discover myofunctional activity during EMG response in left and right anterior temporal, left and right posterior temporal, and left and right masseter muscles to alteration of tooth contacts on occlusal splints during maximal clenching.[20] Actually, they wanted to determine the changes in muscle activity between intercuspal clenching and occlusal splint clenching and monitor any changes in the symmetry or muscle activity as the contacts became more unilateral, where comparisons were made between muscle activity that happened on maximal clenching for the several conditions using the paired t-test at the 0.95 level of significance and the result was not statistically significant.[20] In 1985, Sherman used EMG to describe the activity from the masseteric areas of patients having the primary complaint of pain originating from the region of the TMJ.[21] Here, the patients were grouped into four groups depends on the jaw region having clear TMJ problems with or without physical evidence and history of bruxing or clenching.[21] The result showed 16 patients with clear TMJ problems having no history of bruxing or clenching was neither clinically nor statistically significant, and the mixed problem group was significantly different from the normal.[21] Therefore, it indicates that presence of TMJ problems alone do not lead to increase the level of jaw muscle contraction and amount of muscle contraction is indistinguishable when TMJ is mixed with clenching and bruxing.[21]

Burdette and Gale in 1988 recorded stimulant, postural EMG values from the masseteric and anterior temporal areas of patients having temporomandibular disorders (TMDs) using bipolar surface electrodes for an intensive treatment regimen, which encompassed splinting and psychophysiological therapies.[22] The result indicates that tonic masticatory muscle activity may be raised in patients of myofascial pain dysfunction syndrome (MPDS).[22]

In 1990, Burdette and Gale published an article on reliability of surface EMG of the masseteric and anterior temporalis areas. They studied in 37 patients having myofascial pain dysfunction.[5] The result showed all masseteric and temporalis correlation coefficients were significant where the less exact measure of the level of tonic activity present in these muscle area.[5] In 1990, comparisons of MPDS, TMJD, and back pain patients with healthy controls showed that TMD patients show marked increases in the right masseter EMG levels and drifts toward significantly higher increases at the left masseter during both neutral and stressful images compared to chronic back pain and healthy controls groups.[23] The more pronounced reactivity on the right side was also informed by Katz et al., who noted higher EMG levels at the right temporalis muscle.[23]

In 1991, another study had been conducted by Flor et al. to find out 33 stress-related electromyographic responses in patients with chronic temporomandibular pain, where MPDS patients specified more life stress and gave higher aversiveness grades during the experiment.[6]

In 1993, Lobbezoo et al. showed (healthy subject) that insertion of occlusal appliances in normal, healthy, pain-free males reorganize muscle activity, and splints decreased anterior temporalis muscle electromyographic activity, whereas masseter activity increased.[24] In 1993, Ferrario et al. established a study where the result showed male and female, mean potentials were similar, except in the clinch, where males had higher electromyographic levels and during rest position, and contact in centric occlusion.[1] Ferrario explored electromyograms of children with Class II division 1 malocclusion and found dysfunction of the temporal muscle in habitual occlusion and at rest (increased activity in the posterior part of the temporal muscle).[1] He identified that this dysfunction might be an etiologic cause of postnormal occlusion.[1]

Crider in 2000 had been conducted a study in Sweden to determine the efficacy of electromyographic biofeedback-based treatments and to evaluate the size of treatment effect for TMDs.[25] This review was done from 13 studies, six of which were controlled trials, four were comparative trials, and rest of three were uncontrolled trials.[25]

In 2001, Wieselmann-Penkner et al. proceeded a study to compare the muscular relaxation effect of TENS and EMG-biofeedback in patients with bruxism.[7] In result, EMG activity of the masticatory muscles and skin conductance level of patients of myofascial pain syndrome showed reduced mean-EMG levels for both groups after the treatment periods, with higher EMG values showing in myomonitor group.[7] Another article published by Iyer and Valiathan in 2001 to determine the application of EMG was the main concern.[2] Here, the authors described motor unit potential and electromyographic technique where surface electrodes are more preferable than needle electrodes.[2]

In 2003, Roark et al. used EMG during parafunctional tooth contact to identify the effects of interocclusal appliances.[8] In this study, subjects were instructed to create light tooth contact, maximum full clenching, and adequate clenching of without the splint in place while EMG data from the left and right temporalis and masseter muscles were documented.[8] After a repeated measures analyses of variance between the two conditions, EMG activity showed a significant difference.[8] On the right and left temporalis, clenching task activity of EMG was significantly decreased and the left masseter under moderate clenching remained significantly increased.[8]

In 2004, Ferrario et al. proceeded a study to assess the repeatability of maximal bite force estimates as found by submaxilla electromyographic-force relationships performed simultaneously and symmetrically on both sides of the mouth.[9] The result shown significant linear relationships were found between bite force and EMG potentials.[9]

Drost et al. in 2006 have justified a study on clinical applications of high-density surface EMG as a diagnostic tool in motor neuron diseases, neuropathies, and myopathies (mainly in patients with channelopathies.[10]

In 2008, Castroflorio et al. published a review of surface EMG in the jaw elevator muscles (masseter, temporalis, medial pterygoid, and superior belly of lateral pterygoid) to introduce with recording method, inducing factor, and clinical applications (identifying the etiology of TMD) and got the recording of the surface EMG can ease the reliability and sensitivity of this procedure thus associated with some methodological factors.[11]

De Felício et al. conducted a study in 2012 to evaluate association between surface EMG of masticatory muscles, orofacial myofunctional status, and TMD severity scores, where result showed TMD patients with more asymmetry between right and left muscle pairs, more unstable contractile activities of contralateral masseter and temporal muscles, worse orofacial myofunctional status, and higher TMD severity scores than healthy subjects.[15]

In 2013, Alam et al. showed a study in Malaysia to evaluate malfunction by surface EMG (sEMG) of the face (masseter) and head (temporalis) muscles during brushing teeth Miswak, which may induce a dynamic role in the face and head muscles exercise.[16] The outcome of sEMG showed continuous muscular activity of the temporal and master muscles on both sides of the force and movement of the shoulder joint during brushing teeth with Miswak.[16]

In 2015, a pilot study has been reported by Iwasaki et al. to determine differences in masticatory muscle usage between TMJ disorders diagnostic group. According to this study, temporalis muscle shown significantly higher activity than masseter.[18]

Turcio et al. also conducted a study in 2015 using EMG to evaluate the muscular alterations during the silent period of anterior temporal and masseter muscles influence of oral contraceptive use during the menstrual cycle.[26] Alamet al in 2015 evaluated the satisfaction of patients with posterior implants in relation to the clinical success criteria and surface electromyography (sEMG) findings of the masseter and temporalis muscles. They found the satisfaction of implant patients was high, and which was in relation to the successful clinical success criteria and sEMG findings.[27]

CONCLUSIONS

We establish that EMG has many uses in our general dentistry not only for observation purpose but also for diagnostic and therapeutic purpose. EMG record shows masticatory muscle response both in exercising and resting positions. It is very much helpful in the treatment of bruxism patients by detecting uncontrolled muscle activity. Using forest plot, we assessed the quality of these studies.

Financial support and sponsorship

USM short-term grant (304/PPSG/61312134) and USM RU grant 1001/PPSG/812154.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ferrario VF, Sforza C, D’addona A, Barbini E. Electromyographic activity of human masticatory muscles in normal young people. Statistical evaluation of reference values for clinical applications. J Oral Rehabil. 1993;20:271–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.1993.tb01609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iyer M, Valiathan A. Electromyography and its application in orthodontics. Curr Sci (Bangalore) 2001;80:503–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casas, JM, Beemsterboer P, Clark GT. A comparison of stress-reduction behavioral counseling and contingent nocturnal EMG feedback for the treatment of bruxism. Behav Res Ther. 1982;20:9–15. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(82)90003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamada T, Kotani H, Kawazoe Y, Yamada S. Effect of occlusal splints on the EMG activity of masseter and temporal muscles in bruxism with clinical symptoms. J Oral Rehabil. 1982;9:119–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.1982.tb00541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burdette BH, Gale EN. Reliability of surface electromyography of the masseteric and anterior temporal areas. Arch Oral Biol. 1990;35:747–51. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(90)90098-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flor H, Birbaumer N, Schulte W, Roos R. Stress-related electromyographic responses in patients with chronic temporomandibular pain. Pain. 1991;46:145–52. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90069-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wieselmann-Penkner K, Janda M, Lorenzoni M, Polansky R. A comparison of the muscular relaxation effect of TENS and EMG-biofeedback in patients with bruxism. J Oral Rehabil. 2001;28:849–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2001.00748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roark AL, Glaros AG, O’Mahony AM. Effects of interocclusal appliances on EMG activity during parafunctional tooth contact. J Oral Rehabil. 2003;30:573–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2003.01139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrario VF, Sforza C, Zanotti G, Tartaglia GM. Maximal bite forces in healthy young adults as predicted by surface electromyography. J dent. 2004;32:451–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2004.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drost G, Stegeman DF, van Engelen BG, Zwarts MJ. Clinical applications of high-density surface EMG: a systematic review. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2006;16:586–602. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castroflorio T, Bracco P, Farina D. Surface electromyography in the assessment of jaw elevator muscles. J Oral Rehabil. 2008;35:638–645. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2008.01864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Santana-Mora U, Cudeiro J, Mora-Bermúdez MJ, Rilo-Pousa B, Ferreira-Pinho JC, Otero-Cepeda JL, et al. Changes in EMG activity during clenching in chronic pain patients with unilateral temporomandibular disorders. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2009;19:e543–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watanabe A, Kanemura K, Tanabe N, Fujisawa M. Effect of electromyogram biofeedback on daytime clenching behavior in subjects with masticatory muscle pain. J Prosthet Dent. 2011;55:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jpor.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Endo H, Kanemura K, Tanabe N, Takebe J. Clenching occurring during the day is influenced by psychological factors. J Prosthet Dent. 2011;55:159–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jpor.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Felício CM, Ferreira CLP, Medeiros APM, Da Silva MAMR, Tartaglia GM, Sforza C. Electromyographic indices, orofacial myofunctional status and temporomandibular disorders severity: A correlation study. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2012;22:266–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2011.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alam MK, Basri R, Reza MF. Myofunctional Benefit of Tooth Brushing with Miswak: Electromyography and Magneto encephalography Assessment. Int Med J. 2013;20:247–9. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saito M, Yamaguchi T, Mikami S, Watanabe K, Gotouda A, Okada K et al. Temporal association between sleep apnea–hypopnea and sleep bruxism events. J Sleep Res. 2014;23:196–203. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iwasaki LR, Gonzalez YM, Liu H, Marx DB, Gallo LM, Nickel JC. A pilot study of ambulatory masticatory muscle activities in temporomandibular joint disorders diagnostic groups. Orthod craniofac res. 2015;18:146–55. doi: 10.1111/ocr.12085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kishimoto T. Studies on bruxism. Journal of Japan Orthodontic Society. 1957;16:26 (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wood WW, Tobias DL. EMG response to alteration of tooth contacts on occlusal splints during maximal clenching. J Prosthet Dent. 1984;51:394–6. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(84)90229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sherman RA. Relationships between jaw pain and jaw muscle contraction level: underlying factors and treatment effectiveness. J Prosthet Dent. 1985;54:114–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(85)80084-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burdette BH, Gale EN. The effects of treatment on masticatory muscle activity and mandibular posture in myofascial pain-dysfunction patients. J dent Res. 1988;67:1126–30. doi: 10.1177/00220345880670081301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katz JO, Rugh JD, Hatch JP, Langlais RP, Terezhalmy GT, Borcherding SH. Effect of experimental stress on masseter and temporalis muscle activity in human subjects with temporomandibular disorders. Arch Oral Biol. 1989;34:393–8. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(89)90116-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lobbezoo F, Van Der Glas HW, Van Kampen FMC, Bosman F. The effect of an occlusal stabilization splint and the mode of visual feedback on the activity balance between jaw elevator muscles during isometric contraction. J Dent Res. 1993;72:876–2. doi: 10.1177/00220345930720050801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dahlström L. Efficacy of electromyographic treatment is supported for temporomandibular disorders. Evid Based Dent. 2000;2:69. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leal Turcio KH, Garcia AR, Junqueira Zuim PR, Moreno A, Goiato MC, Guiotti AM, dos Santos DM. Evaluation of silent period on masticatory cycles of different muscles in dentate oral contraceptives users and nonusers. Eur J Dent. 2015;9:171–5. doi: 10.4103/1305-7456.156793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alam MK, Rahaman SA, Basri R, YiTTS, Si-Jie JW, Saha S. Dental Implants–Perceiving Patients’ Satisfaction in Relation to Clinical and Electromyography Study on Implant Patients. PloS one. 2015;10:e0140438. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]