Abstract

Periodontitis is one of the most prevalent threats to oral health as the most common cause of tooth loss. In order to perform effective treatment, a clinical test that detect sites where disease activity is high and predicts periodontal tissue destruction is strongly desired, however, it is still difficult to prognose the periodontal tissue breakdown on the basis of conventional methods. The aim of this study is to examine the usefulness of gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS), which could eventually be used for on-site analysis of metabolites in gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) in order to objectively diagnose periodontitis at a molecular level. GCF samples were collected from two diseased sites (one site with a moderate pocket and another site with a deep pocket) from each patient and from clinically healthy sites of volunteers.

Nineteen metabolites were identified using GC/MS. Total ion current chromatograms showed broad differences in metabolite peak patterns between GCF samples obtained from healthy sites, moderate-pocket sites, and deep-pocket sites. The intensity difference of some metabolites was significant at sites with deep pockets compared to healthy sites. Additionally, metabolite intensities at moderate-pocket sites showed an intermediate profile between the severely diseased sites and healthy sites, which suggested that periodontitis progression could be observed with a changing metabolite profile. Principal component analysis confirmed these observations by clearly delineating healthy sites and sites with deep pockets. These results suggest that metabolomic analysis of GCF could be useful for prediction and diagnosis of periodontal disease in a single visit from a patient and provides the groundwork for establishing a new, on-site diagnostic method for periodontitis.

Keywords: periodontitis, periodontal disease, metabolomics, gingival crevicular fluid, gas chromatography/mass spectrometry, principal component analysis

INTRODUCTION

Periodontitis is an infectious disease that destroys tooth-supporting tissues (periodontal tissue), and is a predominant threat to oral health as the most common cause of tooth loss. Furthermore, clinical and preclinical studies have demonstrated that periodontitis is clearly associated with a variety of systemic conditions and diseases.1,2) Thus, it is very important to diagnose the disease condition and activity of periodontitis in order to provide patients with efficient preventative and treatment protocols. Onset and progression of periodontitis is the result of the interaction between the host and periodontopathic bacteria that inhabit accumulated biofilm in gingival crevices. It is also well known that breakdown of periodontal tissue is provoked by both bacterial products and proinflammatory molecules derived from host cells.

Probing depth (PD), gingival index (GI), and bleeding on probing (BOP) are conventionally used to assess the clinical condition of periodontal tissues. These clinical measurements provide important information about the level of tissue destruction; however, we cannot appropriately evaluate the pathological condition and disease activity by these measurements alone. Therefore, a new method to diagnose periodontal disease conditions is required.

Analysis of proteins has been developed as a tool for identification of useful biomarkers, which can assist in diagnosing and predicting the progression of periodontitis. Gingival crevicular fluid (GCF), a tissue fluid that flows into the gingival crevices, contains many proteins derived not only from the host, but also from bacteria inhabiting accumulated biofilm in gingival crevices. It is well known that there are some differences in the proteins found in GCF collected from clinically healthy sites and sites with chronic periodontitis.3–5) Protein contents in GCF are commonly analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), but there is a limitation in the number of proteins that can be analyzed at one time. Also, conventional methods for analyzing non-protein or novel molecules are time-consuming and may require multiple techniques (and also instrumentation for each technique) to gain a complete analyte profile useful for prediction and diagnosis.

Metabolomic methods including gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC/MS), and capillary electrophoresis mass spectrometry (CE/MS) have been increasingly applied to biomarker detection and disease diagnosis.6) In previous studies of GCF, significant differences in the quantities of observed metabolites between the healthy, gingivitis, and periodontitis sites were reported.7) Many metabolites associated with inflammation, oxidative stress, tissue degradation, and bacterial metabolism were found to be significantly elevated in periodontal disease and reduced by toothbrushing with triclosan-containing dentifrice.8) Metabolomic analysis of saliva in diabetics replicated the metabolite signature of periodontal disease progression in non-diabetic patients and revealed unique metabolic signatures associated with periodontal disease in diabetics.9) In these previous studies, multiple techniques were used to look at a panel of metabolites, however, needing several instruments to perform the analysis on-site would be cumbersome and expensive.

In this study, GCF was analyzed using only GC/MS followed by statistical analysis to identify and correlate characteristic combinations of metabolites that represent pathological condition. While not an optimal chair-side analysis, a GC/MS-only method could be applicable for early diagnosis of periodontal disease during a single visit from a patient. Additionally, this method was investigated in order to make a future transition to a multi-turn time-of-flight mass spectrometer “MULTUM,”10) which is a small mass analyzer with the potential for portable on-site analysis with increased sensitivity (for even earlier diagnosis) and selectivity over using a quadrupole analyzer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Osaka University Graduate School of Dentistry (approval number: H24-E20). Fourteen patients with chronic periodontitis who visited Osaka University Dental Hospital and sixteen clinically healthy volunteers participated in this study after written informed consent. Mean patient age and PD are presented in Table 1 along with standard error.

Table 1. Characteristics of periodontitis patients and healthy volunteers.

| Periodontitis patients | Healthy volunteers | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (range) | 52.2±4.5 (29–77) | 29.7±0.7 (26–36) | |

| n (male/female) | 16 (8/8) | 14 (11/3) | |

| PD (range) | Moderate-pocket site | Deep-pocket site | Healthy site |

| 3.4±0.2 (2–5) | 7.5±0.5 (6–11) | 2.5 ±0.1 (2–3) | |

Sample collection and sample preparation

Periopaper® (Oraflow Inc., NY, USA) was used to collect GCF samples from sites with deep periodontal pockets (deep-pocket site: PD≥6 mm) and sites with moderate pockets (moderate-pocket site: 4≤PD≤5 mm) of each periodontitis patient, and a clinically healthy site (healthy site: PD≤3 mm) of each volunteer. Sample preparation was similar to that previously reported by Nishiumi et al.11) with slight modifications. The Periopaper® was stored at −80°C until use. Low molecular weight metabolites were extracted by soaking the Periopaper® in 450 μL of the solvent mixture (MeOH : H2O : CHCl3=2.5 : 1 : 1). After ultrasonic extraction was performed for 5 min, the solution was centrifuged at 16,000×g for 5 min at 4°C. A 345 μL aliquot of the supernatant was transferred to a clean tube to which 305 μL of distilled water was added. After vortexing, the solution was centrifuged at 16,000×g for 5 min at 4°C. Next, 500 μL of the resulting supernatant was transferred to a clean tube before being concentrated using a vacuum-centrifugal evaporator TOMY MV-100 (Tomy Medico Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The mixture was lyophilized using a freeze dryer EYELA FDU-1200 (Tokyo Rikakikai Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). For oximation, 40 μL of 20 mg/mL methoxyamine hydrochloride dissolved in pyridine was mixed with a lyophilized sample and incubated at 1200 rpm for 90 min at 30°C. Next, 20 μL of N-methyl-N-trimethylsilyl-trifluoroacetamide (MSTFA) was added for derivatization and the mixture was incubated at 1200 rpm for 30 min at 37°C. The mixture was then analyzed by GC/MS.

GC/MS analysis

Analysis was performed using a JMS-Q1000GC (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). A CP-Sil 8 CB for Amines (30 m×0.25 mm i.d.×0.25 μm) capillary column (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used for chromatographic separation. The GC column temperature was programmed to hold at 80°C for 2 min, then rise to 330°C at a rate of 15°C per minute and hold at the final temperature for 6 min. The injector temperature was kept at 230°C, and helium was used as a carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 1.1 mL/min. Samples of 1.0 μL were injected at a split ratio of 10 : 1. Mass spectrometer conditions were as follows: (1) ionization voltage: 70 eV; (2) ionization current: 200 μA; (3) interface temperature: 280°C; (4) ion source temperature: 280°C; (5) mass range: 85–500; (6) detector voltage: 885 V.

Statistical analysis

In metabolomics, principal component analysis (PCA) is commonly used as a linear transformation for observing patterns and classifying multivariate datasets. PCA can be described as an unsupervised algorithm, since it ignores class labels and its goal is to find the directions that maximize variance in a dataset.12) In this study, PCA was performed on normalized peak intensities using Mathematica 10® (Wolfram Research, Champaign, IL, USA). The method for normalizing peak intensities is described below. Variables were not scaled prior to PCA analysis and the covariance method was applied.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

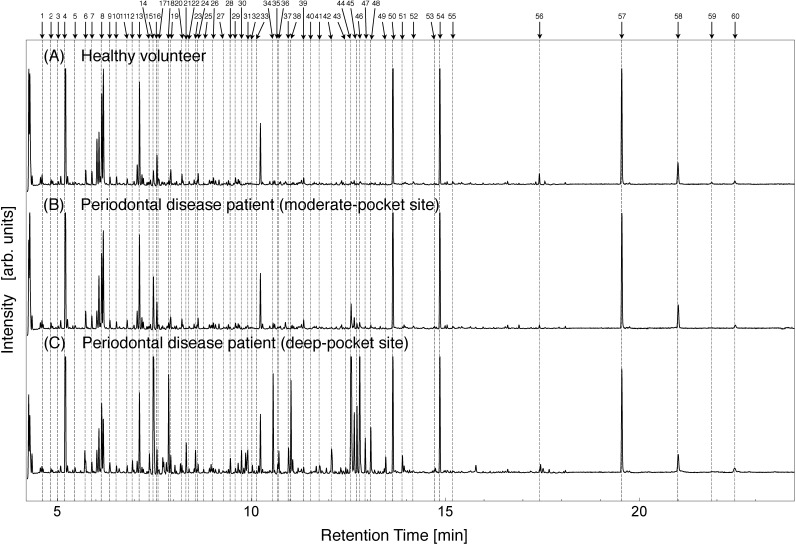

The total ion current (TIC) chromatograms of GCF collected from the clinically healthy sites and diseased sites are shown in Fig. 1. Normalization of the intensity among specimens was carried out using 15 peaks that showed small variability in standard deviation. Peak intensities were derived from peak areas. Normalization procedure is as follows: Ii(n)=intensity of #i peak of #n sample and Pi,j(n)=Ij(n)/Ii(n)=ratio of two peaks (#i and #j). Then we define a group of integer pairs as G∈(i,j)∀RSDi,j<0.5, where RSDi,j=σi,j/μi,j, μi,j=Σn=1~NPi,j(n)/N, and

The top 15 highest frequency members of group G are chosen as group Q. The relative peak intensities in group Q are stable for each sample, so these peaks are used for normalization. The normalization factor for each sample is expressed as S(n)=Σi∈QIi(n). Normalized intensity of each peak is calculated as Ni(n)=Ii(n)/S(n). The peaks used for intensity normalization were as follows: 7, 8, 10, 11, 13, 14, 29, 39, 50, 52, 54, 55, 57, 58, and 60. After normalization, quantitative and chemometric analyses are independent of the amount of GCF collected.

Fig. 1. TIC chromatograms of a healthy site from a volunteer (A) and the moderate-pocket site (B) and deep-pocket site (C) from a patient with periodontal disease.

The TIC chromatograms show that the intensities of some GCF peaks of deep-pocket sites were visibly different compared to healthy sites. In particular, greater intensity of peaks #44, #45, #46, #47, and #48 was observed in the group of deep-pocket sites compared to healthy sites. In general, the intensities for the peaks from moderate-pocket sites were intermediate between those from deep-pocket and healthy sites, as typically observed for peak #15.

The identification of metabolites was performed using a GC/MS database.13) Comparative analysis using reference standards identified 20 peaks as 19 different metabolites (Table 2). It should be noted that two galactose peaks were detected and are the result of an anomeric reaction during the derivitization procedure. Both peaks were included in statistical analysis.

Table 2. Identified metabolites in GCF.

| Peak number | RT [min] | Identified metabolites |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 4.83 | Propyl amine |

| 4 | 5.20 | Lactic acid |

| 14 | 7.37 | Benzoic acid |

| 15 | 7.48 | Phosphate |

| 18 | 7.88 | Glycine |

| 19 | 7.93 | Succinic acid |

| 22 | 8.38 | Alanine |

| 26 | 9.00 | Hydrocinnamate |

| 28 | 9.45 | Malic acid |

| 34 | 10.55 | Glutamic acid |

| 35 | 10.68 | 5-Aminovaleric acid |

| 36 | 10.70 | Phenylalanine |

| 37 | 10.95 | Ribose |

| 38 | 11.03 | Taurine |

| 40 | 11.55 | Putrescine |

| 44 | 12.57 | Galactose |

| 45 | 12.72 | Galactose |

| 46 | 12.78 | Lysine |

| 51 | 13.90 | Inositol |

| 54 | 14.85 | Octadecanoate |

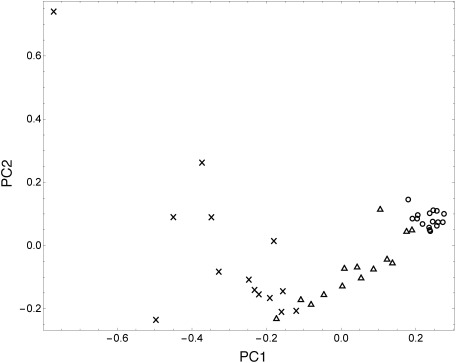

In this study, PCA, which is a basic form of multiple classification analysis, was performed to visualize the pattern of the metabolite intensities in relation to the clinical condition of periodontitis. Analysis was done using peaks 1–60 and the resulting score plot is shown in Fig. 2. The cumulative proportions of the first and second principal components (PC1 and PC2) were 61.21 and 26.82% of the variation, respectively. A tight grouping among healthy sites can be observed indicating that healthy sites share a similar metabolomic profile. There are significant differences between the group of healthy sites and the group of deep-pocket sites. Moderate-pocket sites were widely distributed between healthy and deep-pocket sites, suggesting that Fig. 2 is an illustration of periodontitis progression.

Fig. 2. Score plots of PCA showing healthy volunteers (○), moderate-pocket sites from diseased patients (△), and deep-pocket sites from diseased patients (×). The cumulative proportions of the first and second PCs (PC1 and PC2) were 61.21 and 26.82% of the variation, respectively.

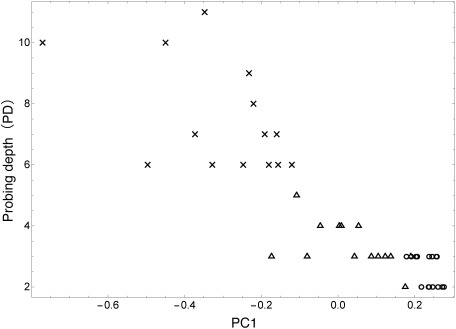

To examine this hypothesis further, PCA scores were compared with probing depth (PD). PD is a conventional clinical parameter used for periodontal examination. It is well known that PD becomes deeper as periodontitis progresses.14,15) The relationship of PC1 and PD is shown in Fig. 3. It can be seen that PC1 values have an inverse relationship with PD and that there is a clear progression of periodontitis from healthy sites to moderate-pocket sites to deep-pocket sites. This result reinforces the change in metabolite concentrations in response to the clinical condition of periodontitis.

Fig. 3. Relationship between scores of PC1 and probing depth. ○ stands for healthy volunteers, △ stands for periodontal disease patient (moderate-pocket site), and × stands for periodontal disease patient (deep-pocket site).

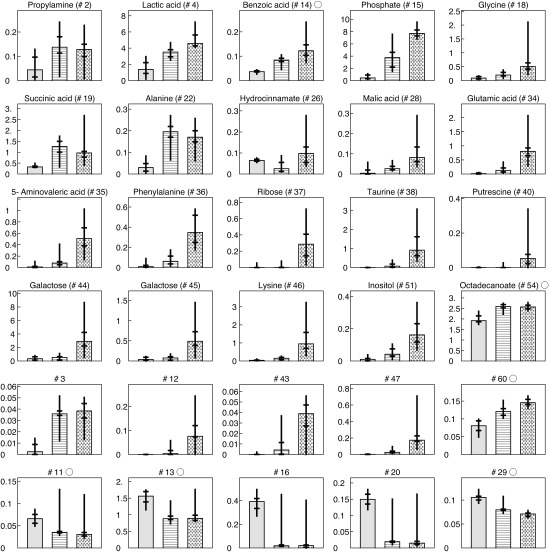

The median value of normalized peak area of each identified metabolite and some significant, unidentified metabolites are shown in Fig. 4. The horizontal and longitudinal bars represent the 50% and 10% confidence intervals, respectively. The peak areas of putrescine, lysine, and phenylalanine were significantly higher in the group of deep-pocket sites in comparison to the group of healthy sites and moderate-pocket sites. This behavior was also reported in a previous study.8) The peak areas of other metabolites (namely, ribose, taurine, 5-aminovaleric acid, and galactose) were also significantly higher in the group of deep-pocket sites in comparison to the group of healthy sites and moderate-pocket sites. While not as pronounced, peak areas of lactic acid, benzoic acid, glycine, malic acid, and phosphate gradually increased from healthy sites to moderate-pocket sites to deep-pocket sites. In Fig. 4, the unidentified metabolites shown in the fifth row exhibit a significant increasing tendency with increasing severity of disease condition, and conversely, unidentified metabolites shown in the sixth row show a significant decreasing tendency. The variation of these metabolite concentrations appears to be heavily related to periodontal disease progression. This relationship was also observed in the PCA analysis. These results suggest that these newly identified metabolites, along with previously identified metabolites, represent pathological condition and that the complexity of the metabolite profile of periodontal disease is much more complex than previously reported. Validation of these claims requires further research with a large sample set.

Fig. 4. The median value of normalized peak area of each metabolites for three groups: the group of healthy volunteers, the group of moderate-pocket sites from periodontal disease patients, and the group of deep-pocket sites from periodontal disease patients. Error bars represent 50% confidence interval.

The identification and quantification of several prospective periodontal disease biomarkers by a GC/MS-only method can now be further developed into an on-site clinical test. A database of healthy and diseased patient GCF metabolite profiles can be developed to allow quick determination of periodontal disease progression by GC/MS measurement followed by multivariate analysis and comparison to the database. Additionally, this method can be applied to future analysis using GC-MULTUM, a GC/MS system developed for portable on-site mass spectral analysis. By focusing GC-MULTUM on just the target metabolites, measurement can be done with increased sensitivity and selectivity, which could facilitate earlier detection of periodontal disease. Further development of metabolomic analysis of GCF by GC-MULTUM could be useful as a future chair-side method in predicting periodontal disease risk during regular patient checkups. Follow-up research on these points is currently underway.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Nineteen metabolites contained in GCF were measured using GC/MS and the resulting spectra were analyzed using PCA. The levels of many identified metabolites increased in response to the clinical condition of periodontitis. Several of these metabolites were newly found to be associated with periodontal disease. Additionally, PCA score plots showed a clear progression of periodontitis with the change in the metabolite profile. Metabolomic analysis of GCF using GC/MS is valuable in the discovery of potential biomarkers and clinical diagnosis and prevention of periodontitis, and could be applied to future on-site analysis and diagnosis using GC-MULTUM. While further studies are required before realizing bedside analysis, an established method using only GC/MS could be applicable for diagnosis during a single visit from a patient.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (24619002, 15K11386) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. The authors wish to thank Dr. Shuichi Shimma of the National Cancer Center Research Institute for his insightful discussions.

Mass Spectrom (Tokyo) 2016; 5(1): A0047

- GCF

Gingival crevicular fluid

- GC/MS

Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry

- TIC

Total ion current

- PCA

Principal component analysis

- PD

Probing depth

- GI

Gingival index

- BOP

Bleeding on probing

- NMR

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- LC/MS

Liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry

- CE/MS

Capillary electrophoresis/mass spectrometry

References

- 1) R. G. Nelson, M. Shlossman, L. M. Budding, D. J. Pettitt, M. F. Saad, R. J. Genco, W. C. Knowler. Periodontal disease and NIDDM in Pima Indians. Diabetes Care 13: 836–840, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2) J. Beck, R. Garcia, G. Heiss, P. S. Vokonas, S. Offenbacher. Periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease. J. Periodontol. 67(Suppl.): 1123–1137, 1996. DOI: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.10s.1123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3) R. C. Baliban, D. Sakellari, Z. Li, P. A. DiMaggio, B. A. Garcia, C. A. Floudas. Novel protein identification methods for biomarker discovery via a proteomic analysis of periodontally healthy and diseased gingival crevicular fluid samples. J. Clin. Periodontol. 39: 203–212, 2012. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2011.01805.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4) S. Tsuchida, M. Satoh, H. Umemura, K. Sogawa, Y. Kawashima, S. Kado, S. Sawai, M. Nishimura, Y. Kodera, K. Matsushita, F. Nomura. Proteomic analysis of gingival crevicular fluid for discovery of novel periodontal disease markers. Proteomics 12: 2190–2202, 2012. DOI: 10.1002/pmic.201100655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5) C. M. Silva-Boghossian, A. P. Colombo, M. Tanaka, C. Rayo, Y. Xiao, W. L. Siqueira. Quantitative proteomic analysis of gingival crevicular fluid in different periodontal conditions. PLoS ONE 8: e75898, 2013. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6) E. M. Lenz, I. D. Wilson. Analytical strategies in metabonomics. J. Proteome Res. 6: 443–458, 2007. DOI: 10.1021/pr0605217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7) V. M. Barnes, R. Teles, H. M. Trivedi, W. Devizio, T. Xu, M. W. Mitchell, M. V. Milburn, L. Guo. Acceleration of purine degradation by periodontal diseases. J. Dent. Res. 88: 851–855, 2009. DOI: 10.1177/0022034509341967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8) V. M. Barnes, R. Teles, H. M. Trivedi, W. Devizio, T. Xu, D. P. Lee, M. W. Mitchell, J. E. Wulff, M. V. Milburn, L. Guo. Assessment of the effects of dentifrice on periodontal disease biomarkers in gingival crevicular fluid. J. Periodontol. 81: 1273–1279, 2010. DOI: 10.1902/jop.2010.100070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9) V. M. Barnes, A. D. Kennedy, F. Panagakos, W. Devizio, H. M. Trivedi, T. Jonsson, L. Guo, S. Cervi, F. A. Scannapieco. Global metabolomic analysis of human saliva and plasma from healthy and diabetic subjects, with and without periodontal disease. PLoS ONE 9: e105181, 2014. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10) S. Shimma, H. Nagao, J. Aoki, K. Takahashi, S. Miki, M. Toyoda. Miniaturized high-resolution time-of-flight mass spectrometer MULTUM-S II with an infinite flight path. Anal. Chem. 82: 8456–8463, 2010. DOI: 10.1021/ac1010348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11) S. Nishiumi, M. Shinohara, A. Ikeda, T. Yoshie, N. Hatano, S. Kakuyama, S. Mizuno, T. Sanuki, H. Kutsumi, E. Fukusaki, T. Azuma, T. Takenawa, M. Yoshida. Serum metabolomics as a novel diagnostic approach for pancreatic cancer. Metabolomics 6: 518–528, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12) A. K. Jain, R. P. W. Duin. Jianchang Mao. Statistical pattern recognition: A review. Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, IEEE Trans. 22: 4–37, 2000. DOI: 10.1109/34.824819 [Google Scholar]

- 13) H. Tsugawa, T. Bamba, M. Shinohara, S. Nishiumi, M. Yoshida, E. Fukusaki. Practical non-targeted gas chromatography/mass spectrometry-based metabolomics platform for metabolic phenotype analysis. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 112: 292–298, 2011. DOI: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2011.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14) G. C. Armitage. Periodontal diagnoses and classification of periodontal diseases. Periodontology 34: 9–21, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15) G. C. Armitage. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann. Periodontol. 4: 1–6, 1999.DOI: 10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]