Abstract

Aim

To determine vitamin D deficiency risk and other lifestyle factors in children aged 2–17 years presenting with an acute fracture to Sunshine Hospital.

Methods

A prospective observational study was undertaken using a convenience sample data collected from children aged 2–17 years of age presenting with an acute fracture. Recruitment was undertaken over a 3-month period from February to May 2014. Risk factors for vitamin D deficiency (skin pigmentation, hours spent outdoors, sunscreen use and obesity) were identified. Patients providing consent, had measurements of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25-OHD). Vitamin D deficiency was defined as < 50 nmol/L.

Results

Of the 163 patients recruited into this study, 134 (82%) had one or more risk factor(s) for vitamin D deficiency. Of these, 109 (81%) consented to 25-OHD testing, with a median of 53 nmol/l (range 14–110 nmol/l) obtained. A total of 57 (52% at risk, 35% of total participants) were found to be vitamin D deficient. 45 (80%) had mild deficiency (30–50 nmol/l) and 11 (20%) had moderate deficiency (12.5–29 nmol/l).

Conclusions

One third of all participants, and the majority participants who had one or more risk factor(s) for vitamin D deficiency, were vitamin D deficient. Based on our findings we recommend that vitamin D status be assessed in all children with risk factor of vitamin D deficiency living in urban environments at higher latitudes presenting with fractures. The effect of vitamin D status on fracture risk and fracture healing in children and teenagers is yet to be determined, as do the effects of vitamin D supplementation in vitamin D deficient paediatric patients presenting with acute fracture.

Keywords: Vitamin D deficiency, Reduced sun exposure, Fracture, Children, Teenagers, Risk factors for vitamin D deficiency

Highlights

-

•

Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency is high in multiethnic children, presenting with fracture with risk factor(s) of vitamin D deficiency.

-

•

Reduced sun exposure or hyperpigmentation have a strong association with vitamin D deficiency.

-

•

Screening for vitamin D deficiency and assessment of dietary calcium adequacy are recommended when a child or teenager presents with an acute fracture.

1. What is already known on this topic

-

1.

Vitamin D is important for maintaining bone health. (See Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5.) (See Table 1, Table 2.)

-

2.

Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency is high in Australia, particularly in southern states.

-

3.

There is a seasonal variation in vitamin D status in southern regions of Australia with higher serum 25-OHD at the end of summer, and lower levels at the end of winter and in early spring.

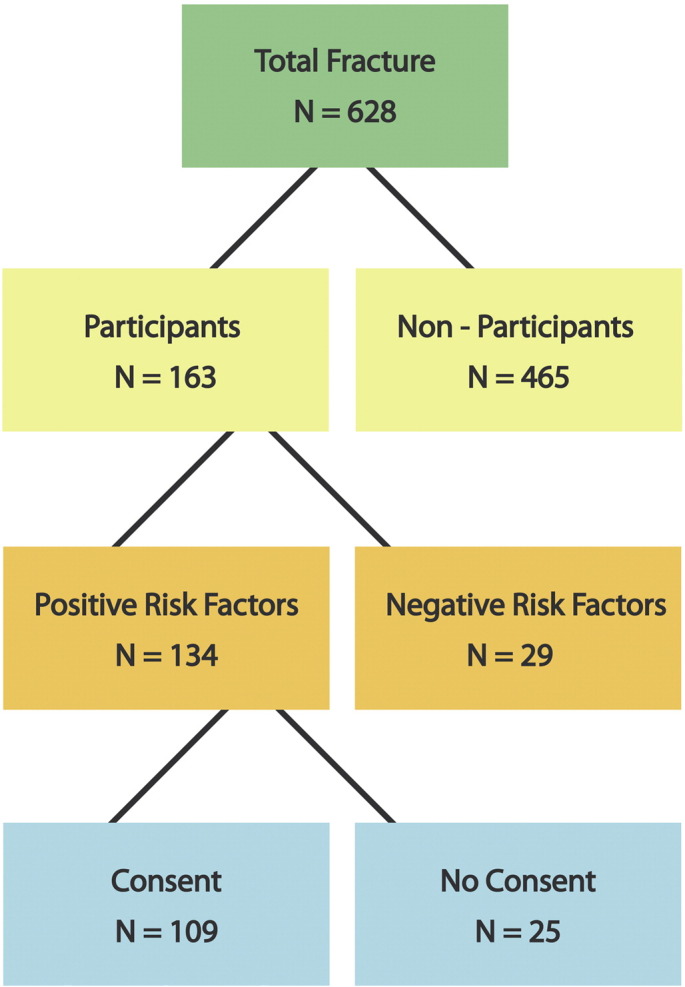

Fig. 1.

Overall recruitment scheme.

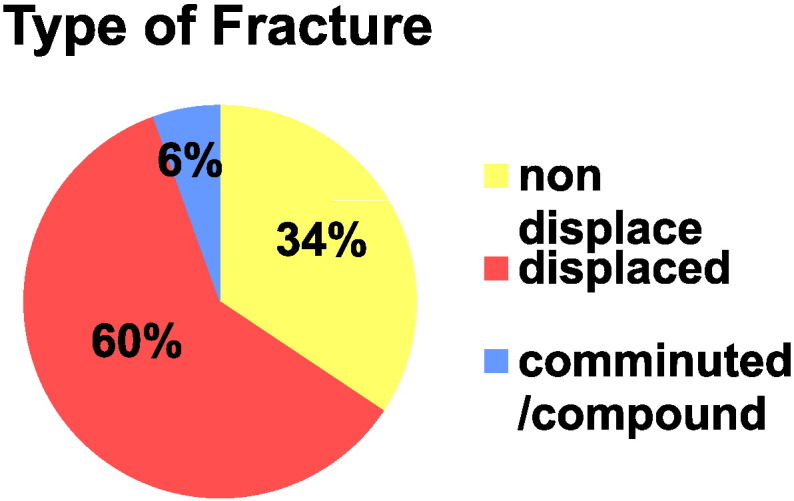

Fig. 2.

Type of fracture.

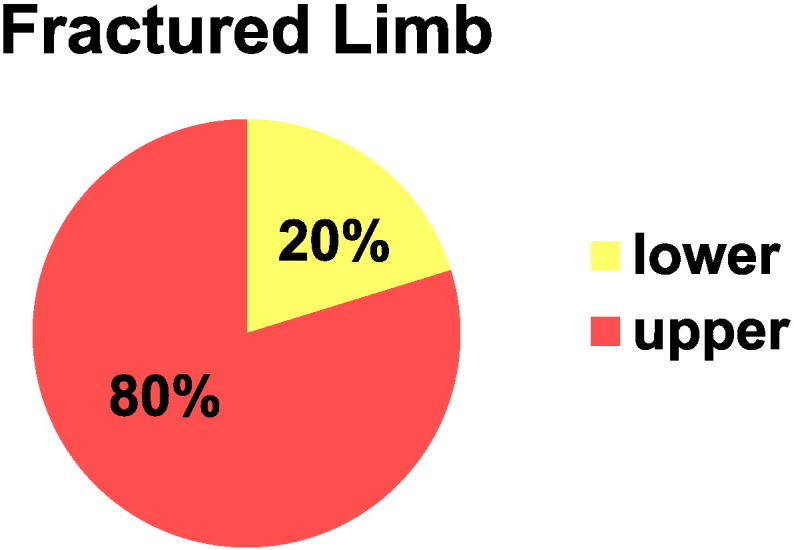

Fig. 3.

Fracture involved limb.

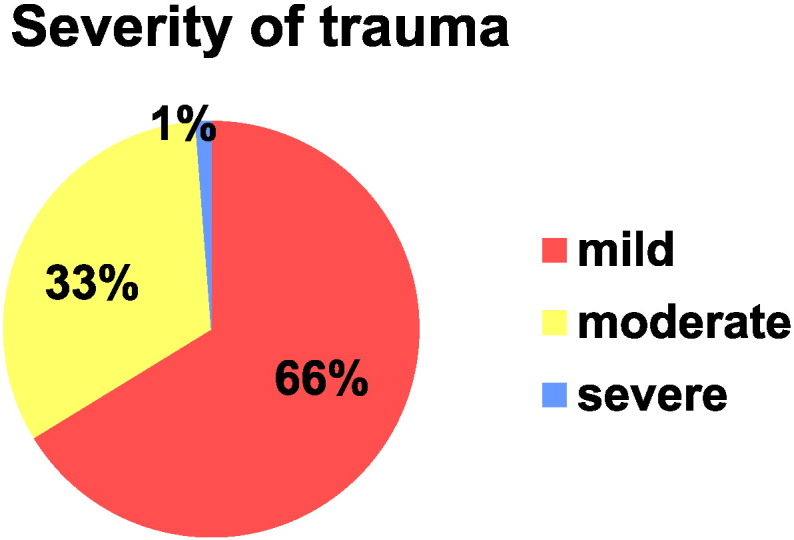

Fig. 4.

Severity of trauma.

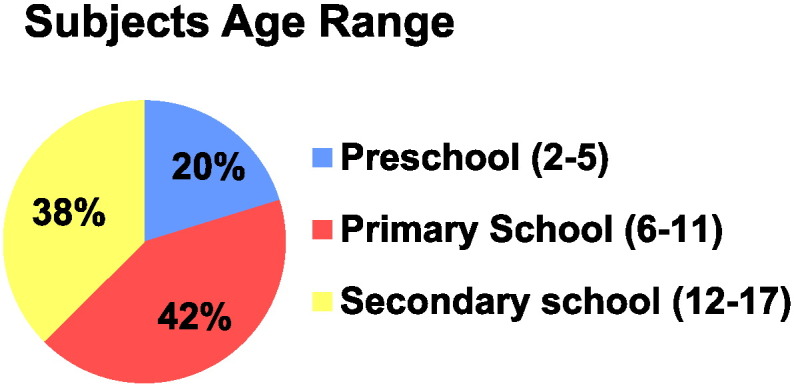

Fig. 5.

Age range of participants.

Table 1.

Chi square test for p-value of risk factors.

| Relationship | P-value |

|---|---|

| Hyperpigmentation ∗ vitamin D deficiency | 0.003 |

| Reduced sun exposure ∗ vitamin D deficiency | 0.000 |

| Obesity ∗ vitamin D deficiency | 0.275 |

Table 2.

Calcium intake and vitamin D deficiency.

| Vit D status |

Sufficient | Deficient | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium intake | |||

| Inadequate | 17 | 34 | 51 |

| Adequate | 7 | 7 | 14 |

| Total | 24 | 41 | 65 |

2. What this paper adds

-

1.

Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency is high in multiethnic children and teenagers, presenting with an acute fracture at the end of summer and with one or more risk factors of vitamin D deficiency.

-

2.

Children and teenagers with reduced sun exposure or hyperpigmentation have a strong association with vitamin D deficiency.

-

3.

Screening for vitamin D deficiency and assessment of dietary calcium adequacy are recommended when a child or teenager presents with an acute fracture.

3. Introduction

One of the major public health issues in older Australians is osteoporosis-related fracture (Jones and Cooley, 2002, Jones et al., 2002, Coughlan and Dockery, 2014, Sanders et al., 1999, Cooley and Jones, 2001). Optimizing bone health in childhood may be critical to improving peak bone mass and potentially reducing the future risk of osteoporosis. Osteoporosis is a disease with its genesis in childhood and adolescence, as peak bone mass is achieved several years after growth cessation, and lifestyle habits established in youth tend to persist throughout adult life (Russell et al., 2006, Matkovic et al., 2004).

Childhood fractures are common and the probability of sustaining a fracture from birth to 50 years of age is nearly 50% (Jones et al., 2002, Landin, 1997, Hedstrom et al., 2010). Peak childhood fracture incidence occurs at 12 years in girls and 14 years in boys (Landin, 1997, Hedstrom et al., 2010, Khosla et al., 2003, Cooper et al., 1995, Ryan et al., 2012, Boyce and Gafni, 2011). This period corresponds to the period immediately following the pubertal growth spurt (Boyce and Gafni, 2011), with attainment of peak bone mass by the age of 18 to 20 years.

As the majority of childhood fractures are due to significant trauma (Plumert, 1995, Schwebel, 2004) and the focus is on immediate fracture management, it is often a missed opportunity to assess children and teenagers regarding preventable osteoporosis risk factors such as vitamin D deficiency, poor dietary calcium intake and sedentary behaviour. The incidence of vitamin D deficiency has increased throughout the world, suggesting it is now endemic and has become a disease of the 21st century (Misra et al., 2008, Clarke and Page, 2012). In Australia, this has been attributed to changes in immigration policies within the last 40 years, which has resulted in more highly pigmented individuals living in Australia; a shift to increasingly indoor lifestyles; and possible overuse of sun screens. Vitamin D deficiency also remains highly prevalent in children in many other countries.

The vast majority of vitamin D is synthesised by skin exposure to UVB, with only a small contribution by dietary intake (Norris, 2001). It is well documented that the prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency is greater in winter and spring because of decreased daily sunlight exposure generally in colder months and reduced or absent UVB wavelength 288 nm which is specifically required for vitamin D synthesis in the skin (van der Mei et al., 2007). People with darker skin pigmentation may require up to 6-times longer UVB exposure compared with fair skinned individuals in order to maintain adequate vitamin D levels because the skin pigment melanin interrupts UVB absorption (Paxton et al., 2013, Clemens et al., 1982, Thomas and DeMay, 2000). Excessive use of sun protection including sunscreen as well as covering due to religious or cultural practices also reduces UVB absorption (Clemens et al., 1982). An inverse relationship between obesity and circulating 25-OHD concentrations has also been reported (Wortsman et al., 2000, Arunabh et al., 2003, Kamycheva et al., 2003, Lagunova et al., 2011, Rajakumar et al., 2011, Khor et al., 2011).

To our knowledge this is the first study to examine the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in otherwise healthy children and adolescents with fractures in an ethnically and culturally diverse population, with a high proportion of highly pigmented individuals. This prospective study examined the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in children and adolescents aged 2–17 years presenting to Sunshine Hospital with a fracture during the 3-month study period during summer-autumn 2014.

4. Patients and methods

4.1. Subjects and assessment of risk factors for vitamin D deficiency

A convenience sample of 163 of the total of 628 paediatric patients who presented to Sunshine Hospital with a fracture during the 3-month study period between February and May 2014 were recruited for this study. Subject recruitment was practically limited as it was conducted by a single student researcher from the Sunshine Hospital Emergency Department, Paediatric Orthopaedic Fracture Clinics, the Paediatric Ward, and the Day Procedure Bay.

Ethics approval was obtained from Royal Children's Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC 33246A) with site-specific authorisation from Western Health Governance office.

At enrolment into this study, all subjects were assessed for risk factor(s) for vitamin D deficiency (Jones and Cooley, 2002) skin pigmentation according to a visual scale described by Lucas et al. (Lucas et al., 2009); (Jones et al., 2002) hours spent outdoors in direct sunlight, (Coughlan and Dockery, 2014) sunscreen use and (Sanders et al., 1999) obesity (BMI > 95th%). Serum 25-OHD concentrations were measured in those at risk, as recommended in the recently published Australian Guidelines by Paxton et al. (Paxton et al., 2013).

There was a total of 163 participants, which was the maximum number of participants the student researcher was able to recruit over the defined study period and of these 134 had one or more positive risk factor(s) for vitamin D deficiency and 109 (81 boys and 28 girls) participants provided written consent for measurement of serum 25-OHD. The remaining 54 participants (29 with negative risk factors and 25 who did not provide a written consent for vitamin D testing) participated only by agreeing to clinical assessment and completion of a 3-day food diary, which was analysed for dietary calcium intake.

4.2. Inclusion criteria

This study included otherwise healthy children aged 2 to 17 years presenting to Sunshine Hospital with a fracture during the 3-month study period between February and May 2014. Serum 25-OHD assays were ordered only for those who provided written consent.

4.3. Exclusion criteria

This study excluded patients who were not able to provide written consent, sustained a minor (undisplaced “hairline”) fracture that did not warrant review in Paediatric Orthopaedic Fracture Clinics, children with any chronic medical conditions, and children regularly taking glucocorticoids or vitamin D supplements.

4.4. Mechanism of injury and severity of fracture

A detailed medical history was taken for all participants which included mechanism of injury, severity of trauma (modified Landin classification (Clark et al., 2008)), type of fracture, history of previous fracture, and history of fracture in parents or siblings were documented.

4.5. Anthropometry

Measurement of height using a wall mounted stadiometer, weight using digital scales, and pubertal assessment by Tanner Staging (Growth and Growth Chart, n.d.) was undertaken in all participants, Body mass index (BMI) was expressed as kg per m2, and obesity defined as greater than the 95th centile using the electronic centile charts on the electronic hospital record (Growth and Growth Chart, n.d.)

4.6. Assessment of skin pigmentation

Skin pigmentation was assessed on the dorsum of the hand using a visual assessment tool published by Lucas et al. (Lucas et al., 2009). The dorsum of the hand was used as skin pigmentation at this site reflects both genetic skin type and increased skin pigmentation in response to UVB exposure.

4.7. Serum vitamin D assay method

A competitive chemiluminescent immunoassay measuring total 25 OHD (LIAISON®, Diasorin) was used with a functional sensitivity: ≤ 10 nmol/L and specificity: 25 OH Vitamin D2 = 104%; 25 OH Vitamin D3 = 100%. There is no interference by the 3-epi isomer of 25 OH Vitamin D.

4.8. 3 day food diary/FoodWorks

An in-house developed 3 day food diary was analysed using FoodWorks 7 (FoodWorks 7 for Window, Xyrics Inc.). Average daily calcium intake was compared with the recommended daily intake (RDI) of calcium (Nutrient Refernce Values for Australia and New Zealand, n.d.).

4.9. Statistical analysis

A Chi square test was performed to identify an association between risk factors and vitamin D deficiency with a commercially available software program (SPSS for Windows, SPSS Inc).

4.10. Outcome measures

We used definitions of vitamin D deficiency according to the Australian guidelines published by Paxton et al. (Paxton et al., 2013) where sufficient vitamin D is greater than 50 nmol/L, mild deficiency from 30 to 50 nmol/L, moderate deficiency from 12.5 to 29 nmol/L, and severe deficiency defined level below 12.5 nmol/L. We defined reduced sun exposure as direct sun exposure of less than 1 h per day on average and/or using sun protection cream two or more times daily on most days.

5. Results

163 participants consented to the study, which is 26% of the 628 paediatric patients who presented to Sunshine Hospital with a fracture during the 3-month study period. A total of 134 out of 163 consented participants had at least one or more risk factor(s) of vitamin D deficiency and a total of 109 out of 134 subjects with positive risk factors for vitamin D deficiency provided further written consent for serum vitamin D assay. Overall there were more boys than girls recruited to this study (male = 112, female = 51) and the mean age for females was 8.5 years and 10 years for males. Of the 109 participants for whom additional consent was obtained for vitamin D assay, the mean (± SD) vitamin D concentration for females and males was 53.6 ± 19.8 nmol/L and 52.5 ± 19.9 nmol/L respectively. 107 (66% of the total) fractures were due to mild trauma and 54 (33%) fractures were involved in moderate trauma and only 2 (1%) fractures were due to severe trauma. 98 (60% of total) fractures were displaced fractures, and forearm fractures were the most common site of fracture accounting for 88 (54% of all fractures). There were 130 upper limb fractures (80%) and 33 lower limb fractures (20%).

Of the 109 participants with vitamin D measurements, 57 subjects (52% at risk, 35% of total subjects) were found to be vitamin D deficient, with 45 subjects (80% of at risk) being mildly deficient, and 12 subjects (20% of at risk) had moderate deficiency. There was a statistically significant association between hyperpigmentation (p = 0.003) and reduced sun exposure (p < 0.001) with vitamin D deficiency. However, the association between obesity and vitamin D deficiency was statistically not significant (p = 0.28), likely reflecting the small numbers of obese subjects recruited.

A 3-day food diary of 106 participants was collected and the mean ± SD daily calcium intake was 590.6 ± 278.1 mg/day and the mean daily calcium intake of 83 participants (78%) was below their age-appropriate RDI. Of the 65 (61%), who completed both the 3-day food diary and had a vitamin D measurement, 41 (63%) were vitamin D deficient and 24 (37%) were vitamin D sufficient. The majority (83%) of vitamin D deficient participants also had inadequate calcium intakes. Only 7 (17%) participants in this group had an adequate intake of calcium, compared with 71% of participants who were vitamin D sufficient. A small minority (11%) of participants had both adequate vitamin D status and achieved the RDI for calcium intake.

6. Discussion

This is the first study in Australia to examine the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in a paediatric fracture convenience sample. There was a high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency (52%) in subjects with risk factor(s) for vitamin D deficiency. A higher prevalence would have been identified if the cut-off were increased to 75 nmol/L, as recommended by some adult population guidelines (Bischoff-Ferrari et al., 2009, Priemel et al., 2010, Bischoff-Ferrari et al., 2005). Furthermore, recruitment for this study was conducted from the end of summer to early autumn when concentrations of vitamin D would be expected to be about 20–40% higher due to seasonal variation at higher latitudes in regions such as Melbourne (38°S) (Daly et al., 2012).

As anticipated, we found a strong correlation between hyperpigmentation and vitamin D deficiency, as well as between reduced sun exposure and vitamin D deficiency. An adult study (Wortsman et al., 2000) identified that obesity decreases vitamin D status because vitamin D sequestration in body fat causes reduced bioavailability of vitamin D from both cutaneous and dietary sources. However, we were unable to confirm this association between obesity and vitamin D deficiency (Wortsman et al., 2000), likely to be due to the small numbers of obese subjects recruited.

Our results provide additional data supporting the importance of sun avoidant/reduced sun exposure lifestyle factors in vitamin D deficiency. We were unable to confirm an association between severity of trauma and vitamin D deficiency. Overall the proportion of upper limb fracture was similar to that previously reported in other paediatric fracture studies (Jones and Cooley, 2002, Jones et al., 2002, Olney et al., 2008), with forearm fractures being 54% (88 participants) of total participants followed by 14.7% (24 participants) with humeral fractures, while total lower limb fractures accounted for 22.6% (37 participants).

We also found a high prevalence of inadequate calcium intake in both vitamin D deficient and sufficient groups, however, due to our small sample size we did not identify a significant association between vitamin D deficiency and inadequate calcium intake.

Currently, screening for vitamin D deficiency in the general paediatric population is generally confined to paediatric patients with concurrent chronic diseases, such as cystic fibrosis and other conditions associated with reduced direct sun exposure related to chronic ill-health resulting in vitamin D deficiency. However, Misra et al. (Misra et al., 2008) suggested that the threshold should be lower for paediatricians screening for vitamin D deficiency if one or more of the following risk factors are present: (1) dark skinned individuals; (2) living in higher latitudes; (3) regular use of glucocorticoids; (4) chronic medical conditions associated with malabsorption; (4) in children with frequent fractures.

This was a small pilot study and recruitment was conducted by single student researcher, therefore limitations for this study are mainly related to practical issues relating to the time required to recruit participants for this study. There were over twice as many children and teenagers presenting with fracture during the study period as we anticipated, and it was not possible to recruit all consecutive eligible patients. The majority of patients who presented to clinic were not successfully recruited mainly because 1) did not consent for study 2) there was no opportunity for the participant to meet the student researcher for recruitment 3) either had fracture of exclusion criteria or attended to clinic for follow up of a previous existing fracture. Consequently the authors accept that the high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency identified may not be representative of the paediatric fracture population as a whole, nor of the whole general paediatric population.

However, we consider that the high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency observed in this study warrants further prospective cohort studies in the paediatric population to determine effects of chronic vitamin D deficiency on fracture risk, fracture healing rates, the risk of future fracture, and how this may be modified by vitamin D supplementation.

7. Conclusion

In conclusion, we found a high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in study participants who had at least one positive risk factor for vitamin D deficiency, especially those who had darkly pigmented skin or reduced sun exposure behaviours. Hence, we recommend screening serum vitamin D in all paediatric patients who present with a fracture with at least one positive risk factor for vitamin D deficiency. However the effects of chronic vitamin D deficiency on fracture risk, fracture healing rates, or risk of subsequent fracture in paediatric populations remain unknown, as do any effects of vitamin D supplementation on ameliorating these potential risks.

Conflict of interest

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the children and teenagers, and their families who participated in this study. We thank Dr. Sharon Brennan for her advice regarding the original study design and Dr. Roslin Boterlo for statistical advice and the support of the Melbourne Medical School for Mr. Dae Kwon who undertook this study as his Scholarly Selective. We also thank Ms. Tamara Sherry, Paediatric Dietician at Sunshine Hospital, for her advice regarding the 3-day food diary and the analyses of calcium intake.

References

- Jones G., Cooley H.M. Symptomatic fracture incidence in those under 50 years of age in southern Tasmania. J. Paediatr. Child Health. 2002;38:278–283. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2002.00811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones I.E., Williams S.M., Dow N., Goulding A. How many children remain fracture-free during growth? A longitudinal study of children and adolescents participating in the Dunedin multidisciplinary health and development study. Osteoporos. Int. 2002;13:990–995. doi: 10.1007/s001980200137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlan T., Dockery F. Osteoporosis and fracture risk in older people. Clin Med. 2014;14:187–191. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.14-2-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders K.M., Seeman E., Ugoni A.M. Age- and gender-specific rate of fractures in Australia: a population-based study. Osteoporos. Int. 1999;10:240–247. doi: 10.1007/s001980050222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooley H., Jones G. A population-based study of fracture incidence in southern Tasmania: lifetime fracture risk and evidence for geographic variations within the same country. Osteoporos. Int. 2001;12:124–130. doi: 10.1007/s001980170144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell R.G., Espina B., Hulley P. Bone biology and the pathogenesis of osteoporosis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2006;18(Suppl. 1):S3–10. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000229521.95384.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matkovic V., Landoll J.D., Badenhop-Stevens N.E. Nutrition influences skeletal development from childhood to adulthood: a study of hip, spine, and forearm in adolescent females. J. Nutr. 2004;134:701S–705S. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.3.701S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landin L.A. Epidemiology of children's fractures. J. Pediatr. Orthop. B. 1997;6:79–83. doi: 10.1097/01202412-199704000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedstrom E.M., Svensson O., Bergstrom U., Michno P. Epidemiology of fractures in children and adolescents. Acta Orthop. 2010;81:148–153. doi: 10.3109/17453671003628780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khosla S., Melton L.J., 3rd, Dekutoski M.B., Achenbach S.J., Oberg A.L., Riggs B.L. Incidence of childhood distal forearm fractures over 30 years: a population-based study. JAMA. 2003;290:1479–1485. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.11.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper C., Cawley M., Bhalla A. Childhood growth, physical activity, and peak bone mass in women. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1995;10:940–947. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650100615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan L.M., Teach S.J., Singer S.A. Bone mineral density and vitamin D status among African American children with forearm fractures. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e553–e560. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce A.M., Gafni R.I. Approach to the child with fractures. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011;96:1943–1952. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plumert J.M. Relations between children's overestimation of their physical abilities and accident proneness. Develop Psychol. 1995;31:866–876. [Google Scholar]

- Schwebel D.C. The role of impulsivity in children's estimation of physical ability: implications for children's unintentional injury risk. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry. 2004;74:584–588. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.74.4.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra M., Pacaud D., Petryk A. Vitamin D deficiency in children and its management: review of current knowledge and recommendations. Pediatrics. 2008;122:398–417. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke N.M., Page J.E. Vitamin D deficiency: a paediatric orthopaedic perspective. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2012;24:46–49. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32834ec8eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris J.M. Can the sunshine vitamin shed light on type 1 diabetes? Lancet. 2001;358:1476–1478. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06570-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Mei I.A., Ponsonby A.L., Engelsen O. The high prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency across Australian populations is only partly explained by season and latitude. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007;115:1132–1139. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxton G.A., Teale G.R., Nowson C.A. Vitamin D and health in pregnancy, infants, children and adolescents in Australia and New Zealand: a position statement. Med. J. Aust. 2013;198:142–143. doi: 10.5694/mja11.11592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens T.L., Adams J.S., Henderson S.L., Holick M.F. Increased skin pigment reduces the capacity of skin to synthesise vitamin D3. Lancet. 1982;1:74–76. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)90214-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas M.K., DeMay M.B. Vitamin D deficiency and disorders of vitamin D metabolism. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2000;29:611–627. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8529(05)70153-5. (viii) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wortsman J., Matsuoka L.Y., Chen T.C., Lu Z., Holick M.F. Decreased bioavailability of vitamin D in obesity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000;72:690–693. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.3.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arunabh S., Pollack S., Yeh J., Aloia J.F. Body fat content and 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels in healthy women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003;88:157–161. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamycheva E., Joakimsen R.M., Jorde R. Intakes of calcium and vitamin d predict body mass index in the population of Northern Norway. J. Nutr. 2003;133:102–106. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagunova Z., Porojnicu A.C., Lindberg F.A., Aksnes L., Moan J. Vitamin D status in Norwegian children and adolescents with excess body weight. Pediatr. Diabetes. 2011;12:120–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2010.00672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajakumar K., de las Heras J., TC C., Lee S., MF H., SA A. Vitamin D status, adiposity, and lipids in black American and Caucasian children. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011;96:1560–1567. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khor G.L., Chee W.S., Shariff Z.M. High prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency and its association with BMI-for-age among primary school children in Kuala Lumpur. Malaysia. BMC public health. 2011;11:95. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas R.M., Ponsonby A.L., Dear K. Associations between silicone skin cast score, cumulative sun exposure, and other factors in the ausimmune study: a multicenter Australian study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2009;18:2887–2894. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark E.M., Ness A.R., Tobias J.H. Bone fragility contributes to the risk of fracture in children, even after moderate and severe trauma. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2008;23:173–179. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.071010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Growth and Growth Chart http://www.apeg.org.au/ClinicalResourcesLinks/GrowthGrowthCharts/tabid/101/Default.aspx (at)

- Nutrient Refernce Values for Australia and New Zealand http://www.nrv.gov.au/nutrients/calcium (at)

- Bischoff-Ferrari H.A., Willett W.C., Wong J.B. Prevention of nonvertebral fractures with oral vitamin D and dose dependency: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009;169:551–561. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priemel M., von Domarus C., Klatte TO Bone mineralization defects and vitamin D deficiency: histomorphometric analysis of iliac crest bone biopsies and circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D in 675 patients. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2010;25:305–312. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff-Ferrari H.A., Willett W.C., Wong J.B., Giovannucci E., Dietrich T., Dawson-Hughes B. Fracture prevention with vitamin D supplementation: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2005;293:2257–2264. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.18.2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly R.M., Gagnon C., Lu Z.X. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and its determinants in Australian adults aged 25 years and older: a national, population-based study. Clin. Endocrinol. 2012;77:26–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olney R.C., Mazur J.M., Pike L.M. Healthy children with frequent fractures: how much evaluation is needed? Pediatrics. 2008;121:890–897. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]