SUMMARY

Forgetting, one part of the brain’s memory management system, provides balance to the encoding and consolidation of new information by removing unused or unwanted memories or by suppressing their expression. Recent studies identified the small G-protein, Rac1, as a key player in the Drosophila mushroom bodies neurons (MBn) for, active forgetting. We subsequently discovered that a few dopaminergic neurons (DAn) that innervate the MBn mediate forgetting. Here we show that Scribble, a scaffolding protein known primarily for its role as a cell polarity determinant, orchestrates the intracellular signaling for normal forgetting. Knocking down scribble expression in either MBn or DAn impairs normal memory loss. Scribble interacts physically and genetically with Rac1, Pak3 and Cofilin within MBn, nucleating a forgetting signalosome that is downstream of dopaminergic inputs that regulate forgetting. These results bind disparate molecular players in active forgetting into a single signaling pathway: Dopamine→Dopamine Receptor→Scribble→Rac→Cofilin.

eTOC Blurb

Forgetting is a well-regulated function of the brain that allows adaptation to an ever-changing environment. This study demonstrates that Scribble, identified originally as a cell polarity determinant protein, regulates memory loss by scaffolding a forgetting signalosome.

INTRODUCTION

Active forgetting, a process necessary for optimal cognitive fitness provides balance to the brain’s efforts to encode and consolidate new and important information by removing unused or unwanted memories or by suppressing their expression (Anderson, 2003; Storm, 2011; Wixted, 2004). In contrast to the extensive efforts made to understand how memories are acquired and consolidated, few neuroscience studies have probed the equally important process of forgetting.

Drosophila has emerged as an outstanding model to identify the circuit, cellular and molecular mechanisms of forgetting. Pioneering molecular genetic studies identified a role for the small G protein Rac1 in forgetting of olfactory memories (Shuai et al., 2010). Overexpression of a dominant negative version of Rac1, which is involved in actin cytoskeleton dynamics,in the mushroom body neurons (MBn) slows aversive olfactory memory decay. Adult expression of a constitutively active Rac1 protein has the opposite effect of accelerating the rate of forgetting (Shuai et al., 2010). Interestingly, another component of actin cytoskeleton machinery was recently implicated in memory forgetting in C.elegans. The RNA binding protein Musashi regulates forgetting by controlling the translation of the Arp2/3 complex, which is involved in actin cytoskeleton branching (Hadziselimovic et al., 2014).

In a separate effort, we recently discovered that a small group of dopaminergic neurons (DAn) that may have functional connectivity with MBn mediate the process of forgetting (Berry et al., 2012). Blocking synaptic output from these cells increases memory retention. Conversely, stimulating the output of these neurons after learning increases memory loss. Moreover, this ongoing dopaminergic (DA) activity is modulated with behavioral state, increasing robustly with locomotor activity and decreasing with rest. Increasing sleep-drive decreases ongoing DA activity, while enhancing memory retention. Conversely, increasing arousal stimulates ongoing DA activity and accelerates DA based forgetting (Berry et al., 2015).

Although forgetting is often thought of as a failure or limitation of the brain, commonly associated with pathological processes, these studies support the view that forgetting is a biologically regulated function of the brain allowing for optimal adaptability to an ever-changing environment. They suggest that olfactory memory systems have dedicated and biologically regulated mechanisms to remove or weaken memories, making forgetting an active process.

Here we show that Scribble (Scrb), a scaffolding protein known primarily for its role as a cell polarity determinant, is required for proper forgetting of olfactory memories. Knocking down scribble expression impairs normal memory forgetting. Moreover, we show that Scrb physically interacts with and functions upstream of Rac1, Pak and Cofilin within MBn, to regulate active forgetting in a signaling pathway that is triggered by the dopamine receptor, DAMB, by the ongoing dopaminergic signal.

RESULTS

Scribble is necessary for proper memory loss

In a large genetic screen employing ~3500 individual RNAi transgenes and the pan-neuronal, nsyb-gal4 driver, we searched for genes whose inhibition (RNAi) produced high memory performance after olfactory classical conditioning using mild electric shock as the unconditioned stimulus (Walkinshaw et al., 2015). We identified scrb as a memory suppressor gene due to the high memory score at 3 hr after conditioning when compared to gal4- and uas-only genetic controls (Figure 1A). Although a uas-only heterozygous control group like that used in Figure 1A has frequently been used to account for possible undesired mutagenic or position effects when employing random P-element insertions into the Drosophila genome, we employed a targeted approach in subsequent experiments that obviates the need for both parental controls. The parental line for the scrb RNAi (scrbRNAi), named 60100, was used throughout our study as the control group. This line contains a P{attP,y+,w3′}VIE-260B docking site selected based on its low level of basal expression, consistent high level of gal4-dependent expression across a range of tissues (http://flybase.org/reports/FBrf0208510.html), and is without behavioral phenotypes as shown below. The line thus controls for non-specific insertional effects of the docking site and RNAi transgene.

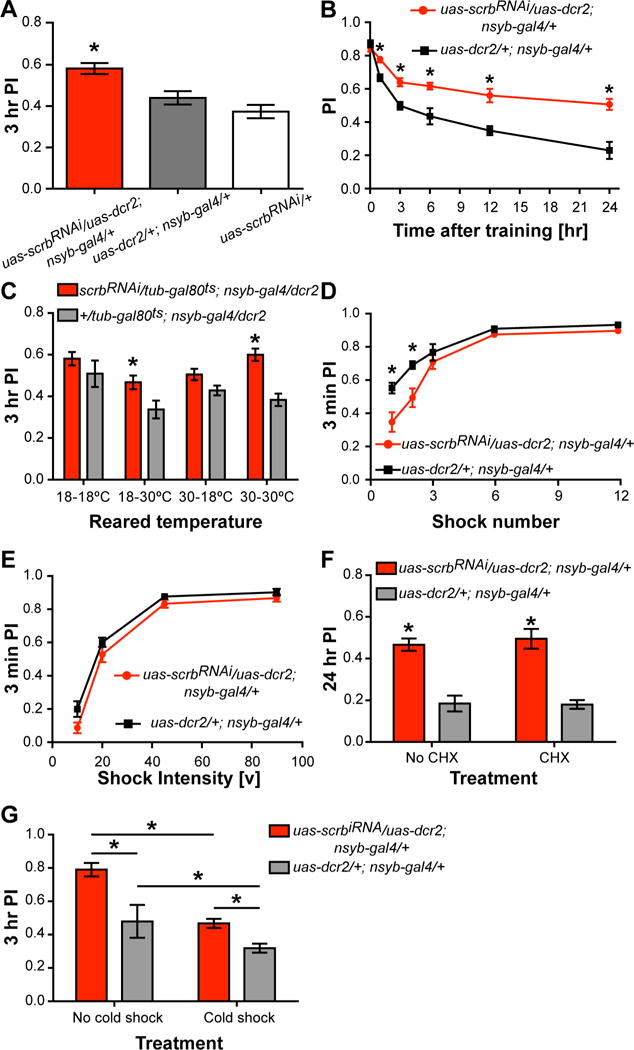

Figure 1. Knocking down scrb impairs memory loss.

(A) Knocking down scrb expression with the pan-neuronal nsyb-gal4 enhanced 3 hr memory performance relative to the gal4- and uas-only control groups. One-way ANOVA, *p<0.05. n = 6. Error bars indicate SEM.

(B) Memory retention is enhanced in scrbRNAi flies. Flies expressing scrbRNAi performed at levels similar to the control group shortly after acquisition but exhibited reduced memory decay when tested at multiple time points after training. Two-way ANOVA, *p<0.05. n = 6. Error bars indicate SEM.

(C) Knocking down scrb expression only during adulthood using the TARGET system increased memory performance. The gal80ts transgene inhibits Gal4 activity at 18° but not at 30°C. Two-way ANOVA, *p<0.05. n = 6–12. Error bars indicate SEM.

(D) Knocking down scrb expression partially impaired acquisition when trained with 1 or 2 shock pulses but not when trained with 3 to 12 shock pulses. Two-way ANOVA, *p<0.05. n = 6. Error bars indicate SEM.

(E) Knocking down scrb expression did not alter memory acquisition when flies were trained with variable shock intensity, Two-way ANOVA. Error bars indicate SEM.

(F) Knockdown of scrb expression did not lead to increased protein synthesis dependent LTM after only one cycle of training. Two-way ANOVA,*p<0.05. n = 6. Error bars indicate SEM.

(G) Down regulation of scrb increased both anesthesia-sensitive and anesthesia-resistant memory. Two-way ANOVA, *p<0.05. n = 6. Error bars indicate SEM.

Scrb is a tumor suppressor and scaffolding protein that has a critical role as an epithelial cell polarity determinant (Bilder, 2000; Bilder and Perrimon, 2000). It is expressed in neurons and is required for normal synaptic structure and function in both invertebrates and vertebrates (Mathew et al., 2002; Moreau et al., 2010; Roche et al., 2002; Sun et al., 2009). We confirmed using qRT-PCR and western blotting that scrbRNAi reduces scrb mRNA and Scrb protein levels by >50% (Figure S1A, B). We also measured by immunohistochemistry the effect of MB (R13F02-gal4) restricted expression of scrbRNAi in MBn and other brain regions, including the ellipsoid body (EB; Figure S1C). Scrb expression with the gal4/uas system does not alter expression outside the normal gal4 expression domain (Figure S1C).

Memory retention studies showed that scrbRNAi-expressing flies exhibit performance levels similar to controls immediately after conditioning but at markedly elevated levels at later times (Figure 1B, S1D). We then found using the TARGET system (McGuire et al., 2003) that expressing scrbRNAi only during adulthood is sufficient to enhance 3 hr memory performance (Figure 1C). This ruled out the possibility that the impairment in forgetting ensues from a developmental effect. Although a scrb mutant, smi97B, was reported to be impaired in olfactory avoidance to benzaldehyde (Ganguly et al., 2003), no significant differences were observed in olfactory and electric shock avoidance for any of the genotypes used for behavioral experiments in our study (Table S1).

The abnormally high memory expression observed in scrbRNAi flies could arise in at least three different ways: (1) increased acquisition leading to elevated memory, (2) normal acquisition but increased consolidation leading to elevated memory, or (3) normal acquisition and consolidation but decreased forgetting. The equivalent performance of control and scrbRNAi flies immediately after conditioning suggested that the increased memory observed at later time points was not due to improved acquisition (Figure 1B). To test this directly and eliminate the possibility of ceiling effects that would mask increased acquisition, we performed two different acquisition experiments by training the flies with an increasing number of shock pulses or twelve pulses of increasing shock intensity. Surprisingly, we observed impaired performance in the acquisition curve of scrbRNAi flies when trained with a limiting number of shock pulses, with a significant difference between scrbRNAi and control flies observed with 1 or 3 shock pulses (Figure 1D). Similar results showing partially impaired acquisition were reported for the damb mutants despite the elevated memory retention observed in this flies (Berry et al., 2012). No significant difference in memory expression was observed between the experimental and control groups using electric shock of differing strengths (Figure 1E). Together, these experiments indicated that enhanced memory in scrbRNAi flies was not due to increased acquisition.

We then tested the possibility that high memory performance was due to improved memory consolidation. We first fed flies with the protein synthesis inhibitor cyclohexamide (CXM), a treatment that blocks the formation of one type of consolidated memory, protein-synthesis dependent long-term memory (LTM) (Tully et al., 1994; Yu et al., 2006). CXM treatment, although impairing LTM formation in control flies (Figure S2), was without effect on the 24 hr memory performance observed for both control and scrbRNAi flies after one cycle of classical conditioning (Figure 1F), indicating that the enhanced memory displayed by these flies is not due to more rapid or efficient consolidation of LTM and furthermore, that the residual memory observed at 24 hr after one cycle of training is protein synthesis independent. We then tested a second form of consolidated memory in Drosophila known as anesthesia resistant memory (ARM). For this experiment we subjected conditioned flies to a cold shock 2 hr after training and measured memory at 3 h. The scrbRNAi flies displayed an elevated memory with and without cold shock, with the magnitude of the elevation over the control in the “cold shock” group being insufficient to account for the magnitude of increase in the “no cold shock” group (Figure 1G). These results revealed that some of the increased memory in scrbRNAi flies remains unconsolidated and some consolidated into ARM.

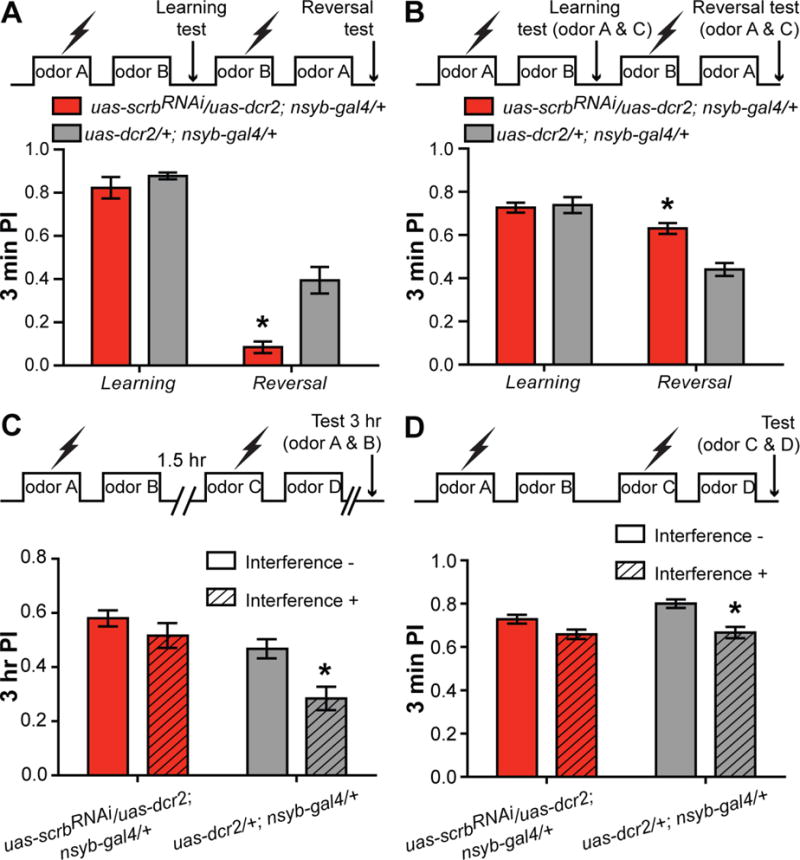

Scribble is required for interference-based induced forgetting

We performed four experiments to test the forgetting processes of scrbRNAi flies using interference-based mechanisms. In the first, we tested the ability of flies to forget and re-write a memory by training flies to a specific odor combination (CS+=A and CS−=B) and immediately after to the opposite contingency (CS+=B and CS−=A). The flies were then tested for memory of the second contingency in this reversal learning experiment (Figure 2A). Control flies typically avoid the odor most recently learned; arguably, because they have the capacity to rapidly update their memories by partly forgetting the no longer “correct” or “less important” odor contingency. A complete impairment in forgetting due to this interference-based procedure would produce two memories with equal strength in aversion and therefore no preference to one of the odors given a choice between the two. Consistent with these predictions, scrbRNAi flies exhibited no performance gains, whereas control flies exhibited considerable performance gains to the second contingency (Figure 2A). We then directly measured the memory of the first odor learned after presenting a second contingency by using a third odor during the memory test. Flies were trained using the same protocol as before but tested with the first odor paired with shock and a never-experienced third odor. The control group given the second training contingency exhibited substantial forgetting, since the second training interfered with memory of the first contingency. The scrbRNAi flies performed significantly better in this assay (Figure 2B). These experimental results also support the impaired forgetting hypothesis over enhanced ARM consolidation in scrbRNAi flies since the experiments span a period of minutes whereas ARM consolidation takes longer. We also performed a retroactive interference experiment by exposing the flies to a second learning session 1.5 hr after the initial one using a completely different odor combination and then testing 3 hr memory. Consistent with impairment in forgetting, scrbRNAi flies exhibited poor retroactive interference produced by a new, unrelated memory (Figure 2C). Finally, we tested whether scrbRNAi impaired proactive interference, a decrement in memory due to a prior learning event. Flies were trained using a C/D odor combination immediately after a training session using an A/B odor combination. Memory was then tested to the second odor contingency. Control flies showed a significantly decreased memory score compared to flies without interference, demonstrating the existence of proactive interference in the controls. However, the proactive interference induced forgetting was impaired in scrbRNAi flies (Figure 2D). The combined results from these experiments exploring the effect of interference on memory retention provided compelling evidence that scrbRNAi flies were unable to update memories after a change in contingency, consistent with the idea that the increased memory performance of scrbRNAi flies results from a failure to forget rather than increased consolidation, Thus, Scrb appears to function in forgetting in ways similar to those reported for Rac1 and the dopamine receptor, Damb (Berry et al., 2012; Shuai et al., 2010).

Figure 2. Knocking down scrb expression impairs interference-based forgetting.

(A) Control flies trained with a reversed contingency expressed considerable memory to the more recent learning event, but scrbRNAi flies exhibited impaired forgetting demonstrated by poor performance to the reversed contingency. Two-way ANOVA, *p<0.05. n = 6. Error bars indicate SEM.

(B) When trained to a reversed contingency but using a third odor for the test to measure the memory performance exclusively to odor A, scrbRNAi flies performed significantly better than control flies. Two-way ANOVA, *p<0.05. n = 6. Error bars indicate SEM.

(C) The scrbRNAi flies were impaired in retroactive interference introduced by new learning occurring 1.5 h after the first learning episode. Two-way ANOVA, *p<0.05. n = 9. Error bars indicate SEM.

(D) Proactive interference decreased memory performance in control but not scrbRNAi flies. Two-way ANOVA, *p<0.05. n = 6. Error bars indicate SEM.

Scribble is required in MBn and DAn for proper memory loss

To determine where in the brain Scrb is required to regulate forgetting, we expressed the scrbRNAi using a battery of gal4 lines that drive expression in different brain regions that are thought or known to be involved in olfactory memory (Figure 3A). Surprisingly, expression in two different groups of neurons, DAn and MBn, but no others, increased 3 hr memory. Thus, the memory suppressor function of Scrb occurs in both DAn and MBn, groups of neurons that have previously been shown to be involved in the formation of new memories and also in forgetting (Berry et al., 2012; Shuai et al., 2010). Expression of scrbRNAi specifically in MBn and DAn showed similar memory acquisition and decay compared to pan neuronal KD of scrb (Figure S3).

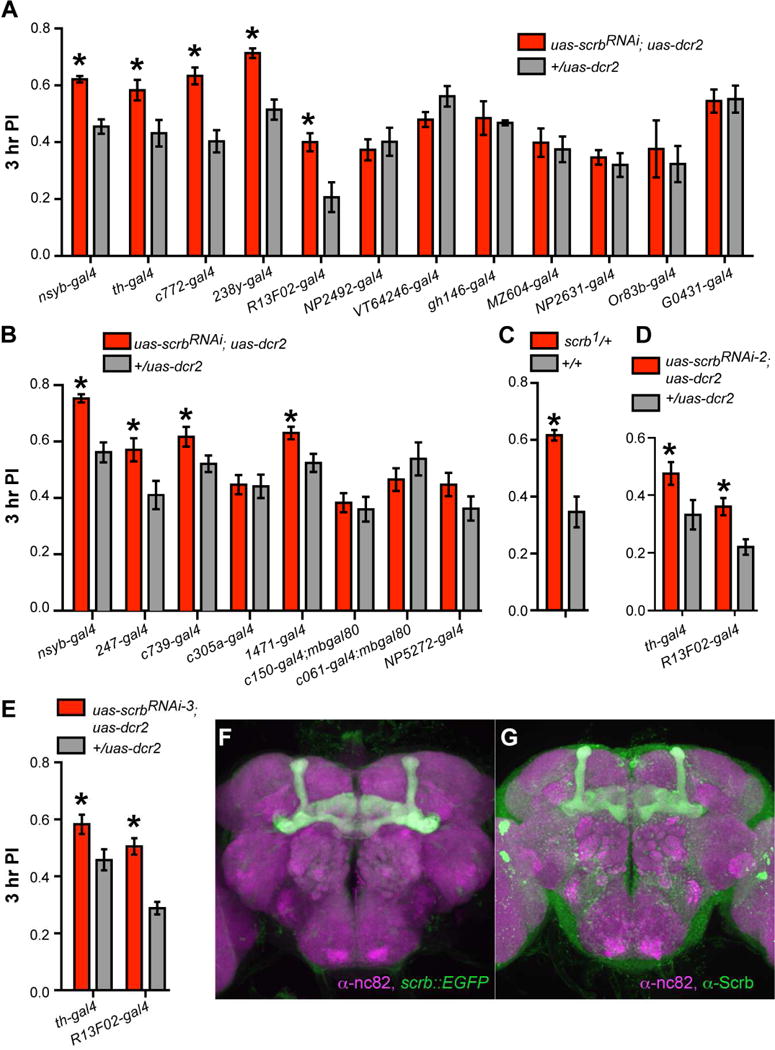

Figure 3. Scrb is required in MBn and DAn for normal memory loss.

(A) The scrbRNAi line was crossed to the gal4 lines listed. Knocking down scrb expression in MBn (c772-gal4, 238y-gal4, R13F02-gal4) or DAn (th-gal4) enhanced memory retention. Pairwise t test, *p<0.05. n = 6. Error bars indicate SEM.

(B) Knocking down scrb expression in α/β (c739-gal4) and/or γ (1471-gal4; 247-gal4) MBn enhanced memory retention. Pairwise t test, *p<0.05. n = 6. Error bars indicate SEM.

(C) The scrb1 heterozygous mutants exhibited enhanced 3 hr memory. Pairwise t test, *p<0.05. n = 6. Error bars indicate SEM.

(D, E) Knocking down scrb expression in MBn and DAn using a second and third RNAi line enhanced memory performance. Pairwise t test, *p<0.05. n = 6. Error bars indicate SEM.

(F) Endogenous expression of scrb::GFPCA07683 in the Drosophila brain, immunostained with anti-GFP and anti-nc82 antibodies.

(G) Endogenous expression of Scrb in Drosophila brain, immunostained with anti-Scrb and anti-nc82.

MBn are subdivided into three main types: α/β, α′/β′ and γ MBn (Crittenden et al., 1998). To further map the memory suppressor function of Scrb, scrbRNAi was expressed in these MBn subtypes using an additional battery of specific gal4 drivers. Memory enhancement was observed when scrbRNAi was expressed in α/β, γ, α/β+γ but not α′/β′ MBn (Figure 3B). Thus, these results map the memory suppressing function of Scrb onto the same set of MBn that require Damb and Rac1 for forgetting (Han et al., 1996; Shuai et al., 2010). There are also several classes of DAn, subdivided according to their projection pattern onto the MB neuropil (Tanaka et al., 2008; Mao et al., 2009). Expression of scrbRNAi in V1+MV1+MP1 (c150-gal4), MP1 (c061-gal4) and M3 (NP5272-gal4) DAn was without effect on memory performance (Figure 3B), suggesting that Scrb is required for memory suppression in a larger set of DAn delimited by the TH-gal4 driver. The expression pattern of all gal4 lines used in this study as revealed by immunohistochemistry is shown in Figure S4. We confirmed the memory suppressor role for Scrb using flies heterozygous for scrb1 (Figure 3C; Bilder and Perrimon, 2000), and Scrb effects on forgetting in MBn and DAn using two additional RNAi lines that target different regions of the Scrb mRNA compared to scrbRNAi (Figure 3D, E).

We then investigated the endogenous expression pattern of Scrb protein using a scrb gene trap line, scrb::GFPCA07683 and immunohistochemistry to EGFP (Buszczak et al., 2007). The expression pattern of Scrb revealed by scrb::GFPCA07683 showed strong expression in the MB calyx and the α/β and γ MB neuropil but not α′/β′ MB neuropil (Figure 3F, Movie S1), in accordance with the mapping of Scrb behavioral functions (Figure 3A, B) to MBn and DAn. We also observed expression in the EB, the fan-shape body, and more limited expression in the antennal lobes and protocerebral bridge. A similar expression pattern was observed when brains were probed using an anti-Scrb antibody (Figure 3G). Knocking down scrb expression using the MB-specific R13F02-gal4 driver confirmed that expression observed in MB lobes arises primarily from MBn and not other MB extrinsic neurons (Movie S2), with the knockdown being most pronounced in the MBγ neurons.

The DA forgetting signal is upstream of Scribble and Rac1 in the regulation of forgetting

We recently proposed that the continuous release of DA, regulated in part by the behavioral state of the animal, engages the Damb receptor expressed by the MBn and activates a signaling pathway leading to the forgetting of recently acquired memories (Berry et al., 2015; Berry et al., 2012). We performed epistasis experiments to explore the relationship between the DA signal, Damb receptor, Rac1, and Scrb to uncover their potential relationships to one another in active forgetting.

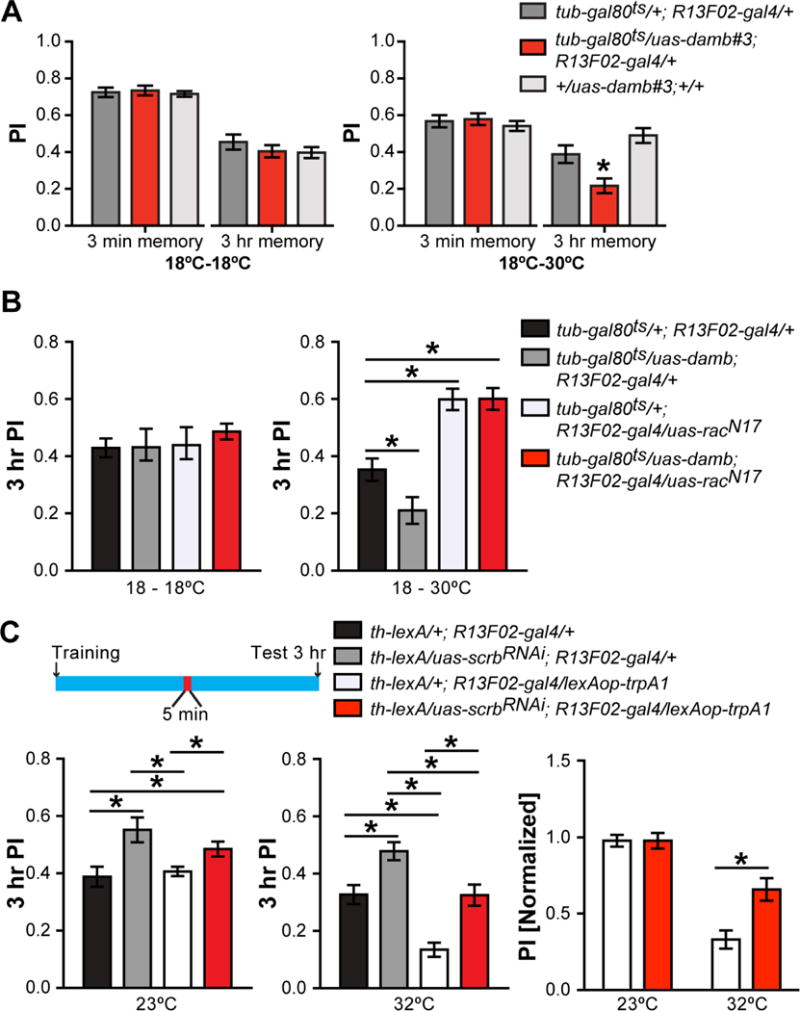

Our prior studies demonstrated that Damb receptor mutants exhibited impaired forgetting (Berry et al., 2012). We asked here whether Damb abundance is a limiting factor for forgetting by overexpressing the receptor in adult MBn using the TARGET system (Figure 4A,B). The results indicated that Damb receptor overexpression in these neurons using the uas-damb#3 transgene decreases 3 hr memory without effects on immediate memory, showing that the levels of Damb receptor in control flies, limits the magnitude of forgetting (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. DAn activity is upstream of Rac1 and Scrb in the regulation of forgetting.

(A) Overexpressing the uas-damb transgene in MBn of adult flies impaired 3 hr memory but left learning intact. One-way ANOVA, *p<0.05. Error bars indicate SEM.

(B) Overexpression of the Damb receptor in MBn during adulthood accelerated forgetting. Co-expression of the Damb receptor and dominant negative Rac1N17 phenocopied the expression of Rac1N17 alone (right panel). Flies of the various genotypes maintained at 18°C during adulthood performed with no significant differences (left panel). One-way ANOVA, *p<0.05. n = 6. Error bars indicate SEM.

(C) Flies were stimulated at 32°C for 5 min at 1.5 hr after training and memory was tested at 3 h. The control flies, maintained at 23°C (left panel), showed a significant increase in performance when scrb was knocked down in MBn (grey and red bars) compared to their respective control groups (black and white bars). TrpA1-based stimulation of DAn neurons induced forgetting (white bar; middle panel) but this effect was partially suppressed when scrb was knocked down in the MBn (red bar). The right panel illustrates the magnitude of the suppression due to scrb inhibition when the performance of the two relevant genotypes at 32°C (middle panel) was normalized to their performance at 23°C (left panel). One-way ANOVA, *p<0.05. n = 6. Error bars indicate SEM.

We then asked whether the Damb receptor and Rac1 are part of the same biochemical forgetting pathway by combining the overexpression of Damb which promotes forgetting with the expression of Rac1N17, which impairs forgetting (Shuai et al., 2010). This experiment utilized a MBn-specific gal4 driver and the TARGET system, such that the potential Damb/Rac1 interactions occur specifically in the adult MBn. We predicted that: (1) the accelerated forgetting phenotype of Damb overexpression would be observed if Damb and Rac1 are in the same pathway with Damb functioning downstream of Rac1, (2) the accelerated forgetting phenotype of Damb overexpression would be balanced by the delayed forgetting phenotype of Rac1N17 expression if they function in separate pathways, or (3) the delayed forgetting phenotype of Rac1N17 expression would be observed if Damb function was upstream of Rac1in the same pathway. Our results revealed that MBn restricted expression of RacN17 along with Damb overexpression produced the phenotype observed with RacN17 expression alone (Figure 4B). This important result indicated that Rac1 is downstream of Damb in the same pathway for forgetting in the MBn; thus merging the previously reported Rac1-based forgetting system (Shuai et al., 2010) and the DA-based forgetting system (Berry et al., 2012) into a single signaling pathway.

We then expressed scrbRNAi specifically in the MBn and thermogenetically activated the DAn using the heat-activated channel, TrpA1. For this experiment, TrpA1 was expressed in DAn using the lexA-lexAop system. We predicted that if Scrb is downstream of the DAn signal, then scrbRNAi expression in the MBn should block the accelerated forgetting caused by excessive DAn signaling. Expression of scrbRNAi by itself in MBn at both 23 and 32°C enhanced memory as expected (Figure 4C). In addition, TrpA1-dependent stimulation of DAn using high temperature accelerated forgetting (Figure 4C). Importantly, scrbRNAi expression in MBn partially protected memory from accelerated forgetting due to the strong activation of DAn with TrpA1 (Figure 4C). The partial protection conferred by scrb knockdown is likely due to the imbalance between the two signals; the partial knockdown of scrb and/or the potent increase in DAn signaling due to TrpA activation. These results support the model that the Scrb protein in the MBn participates in reading the forgetting signal supplied by the DAn.

Scribble physically and genetically interacts with Rac1, Pak3 and Cofilin, scaffolding a signalosome for DA-based, active forgetting

Previous studies have shown that Scrb interacts with and is directly involved in the activation of Rac1 (Wigerius et al., 2013; Nola et al., 2008; Zhan et al., 2008). In addition, Scrb is known to interact physically with p21-activated protein kinases (Pak; Bahri et al., 2010; Nola et al., 2008). The Paks are directly activated by binding to membrane associated Rac1-GTP and subsequently inactivate the actin depolymerizing agent Cofilin by phosphorylation. These observations along with the results above led us to formulate the hypothesis that Scrb may be functionally upstream of Rac1 in the Drosophila MBn, scaffolding a protein complex for forgetting that may include Rac1, Pak, and cofilin.

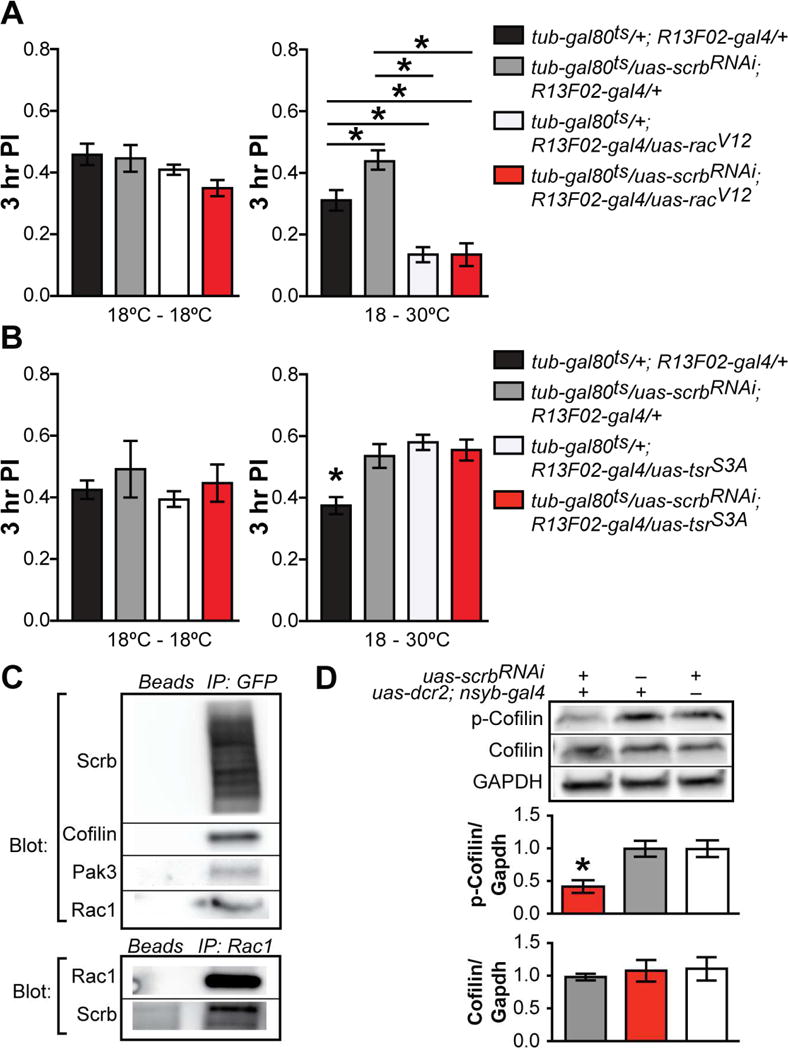

To test for functional interactions, we co-expressed Rac1V12 and scrbRNAi specifically in the adult MBn. We observed the Rac1V12 phenotype in this epistasis experiment (Figure 5A), consistent with the model that Scrb is upstream of Rac1 in the biochemistry of memory forgetting. We also tested the hypothesis that Scrb is functionally in the same signaling pathway as Cofilin. For this, we co-expressed a constitutively active form of Cofilin (tsrS3A) and scrbRNAi in MBn, predicting that the increased memory retention observed in scrbRNAi flies and in flies overexpressing tsrS3A would be additive if in separate pathways, and non-additive if they participated functionally in the same signaling pathway. Consistent with the latter possibility, no additive effect was observed (Figure 5B). Although these were not classical epistasis experiments using null mutant alleles, the results are consistent with the model that Scrb genetically interacts with Rac1 and Cofilin for the regulation of forgetting.

Figure 5. Scribble physically and genetically interacts with Rac1, Pak3 and Cofilin, scaffolding a signalosome for active forgetting.

(A) Expressing constitutively active Rac1 (Rac1V12) in adult MBn accelerated forgetting even when scrb was knocked down in same neurons (right panel). Flies of the various genotypes maintained at 18°C during adulthood performed with no significant differences (left panel). One-way ANOVA, *p<0.05. n = 6–10. Error bars indicate SEM.

(B) Expressing constitutively active Cofilin (tsrS3A) or scrbRNAi in adult MBn impaired memory loss. Co-expression of tsrS3A and scrbRNAi did not further reduce forgetting (right panel). Flies of the various genotypes maintained at 18°C during adulthood performed with no significant differences (left panel). One-way ANOVA, * p<0.05. n = 6. Error bars indicate SEM.

(C) Scrb was immunoprecipitated using scrb::GFPCA07683 flies and anti-GFP antibodies. The Scrb immunoprecipitate co-immunoprecipitated Rac1, Pak3 and Cofilin (upper panel). Immunoprecipitates of Rac1 co-immunoprecipitated Scrb (lower panel).

(D) Pan-neuronal knockdown of Scrb significantly reduced the levels of inactive p-Cofilin but not to total Cofilin compared to control groups. One-way ANOVA, *p<0.05. n=4. Error bars indicate SEM.

We then tested whether Scrb physically associates with proteins involved in forgetting and scaffolds a forgetting signalosome. For this purpose we immunoprecipitated (IP) Scrb using scrb::GFPCA07683 flies and anti-GFP antibodies and probed the immunoprecipitates with antibodies to candidate binding partners. Western blots of fly head extracts were first employed to identify Scrb and its potential binding partners (Figure S5). The Scrb:GFP fusion protein, which is predicted to have multiple isoforms, was identified as a series of bands ranging from ~80 to >250kDa. The candidate proteins were identified as bands running according to their predicted molecular weight: Cofilin (19 kDa), Pak3 (66 kDa), Rac1 (21KDa) and Gapdh (35 KDa). After IP transfer, membranes were stripped and probed with individual antibodies. The results revealed that Scrb interacts physically with Rac1, Pak3 and Cofilin (Figure 5C). As described in prior studies (Wigerius et al., 2013), the interaction with Rac1 was weak and observed in only five of seven assays performed. To confirm this physical interaction, we probed Rac1 immunoprecipitates with an anti-Scrb antibody and observed the interaction in this reciprocal assay (Figure 5C).

Finally, we assayed the effect of Scrb knockdown on Rac1→Pak3→Cofilin signaling. We expressed scrbRNAi using nsyb-gal4 and measured the levels of the final product of this signaling cascade, phospho-Cofilin. Scrb knockdown significantly reduced the levels of p-Cofilin (Figure 5D), the inactive form of Cofilin. Altogether, these results indicated that Scrb physically and genetically interacts with the signaling proteins Rac1, Pak and Cofilin, regulating memory loss by scaffolding a forgetting signalosome activated by the dopaminergic forgetting signal.

Scribble is required to maintain normal ongoing dopaminergic neuron activity

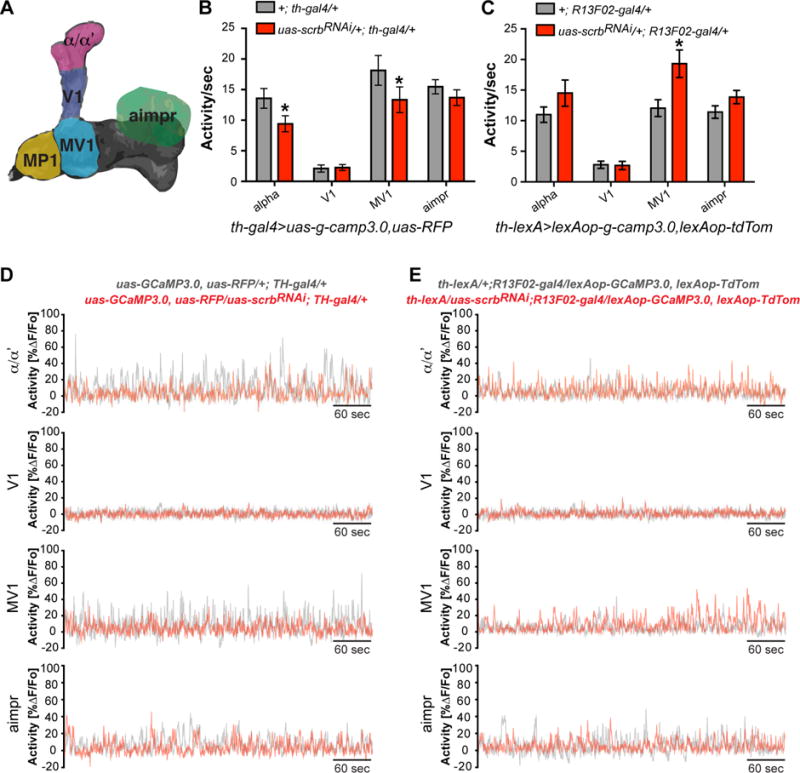

Since Scrb is a scaffolding protein expressed in both pre- and postsynaptic specializations for proper synaptic structure and function (Mathew et al., 2002; Moreau et al., 2010; Roche et al., 2002; Sun et al., 2009), and functions as a memory suppressor protein in both DAn and MBn, we reasoned that Scrb might be involved in DAn-MB signaling but also in the generation or maintenance of DAn ongoing activity. To explore this general idea we posed the following question: Does scrbRNAi alter DAn ongoing activity?

Scrb mutants have been reported to alter both frequency and amplitude of spontaneous synaptic currents in flies and mice (Moreau et al., 2010; Roche et al., 2002) and so we measured the spontaneous calcium transients previously observed in DAns that represent the forgetting signal (Berry et al., 2012). We recorded the ongoing activity of DAn (Figure 6A) using the calcium reporter G-CaMP3.0 while expressing scrbRNAi in either the DAn or MBn. In the first experiment, we expressed scrbRNAi, G-CaMP3.0 and RFP in DAn using the th-gal4 driver. Expression of scrbRNAi in DAn significantly reduced ongoing activity in DAn processes projecting to the α/α′ tip and MV1 regions (Figure 6B, 6D). No changes were detected in DAn projections to V1 or aimpr. These results suggested that scrbRNAi in DAn significantly reduces the forgetting signal defined by DAn ongoing activity, explaining the impairment in forgetting with scrbRNAi in the DAn.

Figure 6. Scrb is required in DAn to maintain normal ongoing activity.

(A) Schematic diagram illustrating the regions of interest recorded for DAn projections to the MB lobes.

(B) Knocking down scrb using th-gal4 decreased DAn ongoing activity in the α/α′ and MV1 regions but not V1 or aimpr. Pairwise Mann Whitney test, *p<0.05. n = 12–23. Error bars indicate SEM.

(C) Knocking down scrb using R13F02-gal4 increased the DAn ongoing activity in the MV1 region but not in α/α′, V1 and aimpr neuropil regions. Pairwise Mann Whitney test, *p<0.05. n = 20–37. Error bars indicate SEM.

(D) Representative recordings of DAn spontaneous activity in flies where scrb expression was reduced using the th-gal4 driver (red) compared to control flies (gray). Ten minute recordings of the DAn processes in the α/α′, V1, MV1 and aimpr regions.

(E) Representative recordings of DAn spontaneous activity in flies where scrb expression was reduced using the R13F02-gal4 driver (red) compared to control flies (gray). Ten minute recordings of the DAn processes in the α/α′, V1, MV1 and aimpr regions.

We then performed the reciprocal experiment, testing the effects of scrbRNAi expression in the MBn on the DAn forgetting signal. To accomplish this, we generated a th-lexA transgene to drive lexAop-g-camp3.0 and td-tomato expression in DAn while expressing uas-scrbRNAi in MBn with R13F02-gal4 (Berry et al., 2015). Opposite to what we expected, scrbRNAi in MBn significantly increased the spontaneous activity of DAn projecting to the MV1 region of the MB lobes (Figure 6C, 6E). Activity in DAn projections to the α/α′ lobe tips as well as the V1 and aimpr areas remained unaltered. These results suggested the existence of a retrograde homeostatic control signal on DAn activity (Davis, 2013). Acting alone, such increased DAn activity would be expected to produce increased forgetting, but MBn lacking Scrb function would make this increased activity unreadable.

Since DAn activity increases with arousal and decreases with rest (Berry et al., 2015) we questioned whether the expression of scrbRNAi influences the state of arousal. We failed to find any significant alterations in the sleep/wake cycle of flies expressing scrbRNAi in either MBn or DAn (Figure S6). This indicates that the observed effects of scrbRNAi on DAn activity and memory are not the indirect effects of altering behavioral arousal patterns.

DISCUSSION

Here we demonstrate that Scrb is a new player that orchestrates a signaling complex employed in the biology of forgetting. This conclusion is draw from four lines of evidence. First, scrb knockdown flies show slower memory decay after aversive conditioning. This impairment is not due to increased memory acquisition or consolidation of protein synthesis-dependent memory (Figure 1). Although scrb knockdown flies have increased ARM (Figure 1G), behavioral experiments demonstrated that Scrb knockdown has a primary deficit in interference induced forgetting (Figure 2). Second, Scrb is expressed and required within the nodes of the circuit required for adult fly memory formation and memory forgetting, including MBn (α/β and γ neurons) and DAn (Figure 3). Third, epistasis experiments show that Scrb works at the interface between ongoing DA signaling and Rac1 activation/Cofilin phosphorylation (Figures 4, 5), being functionally downstream of the ongoing DA signaling and the Damb receptor, and upstream of Rac1 and Cofilin. Fourth, Scrb interacts physically with Rac1, Pak3, and Cofilin (Figure 5) and through its scaffolding function orchestrates a signalosome employed for active forgetting.

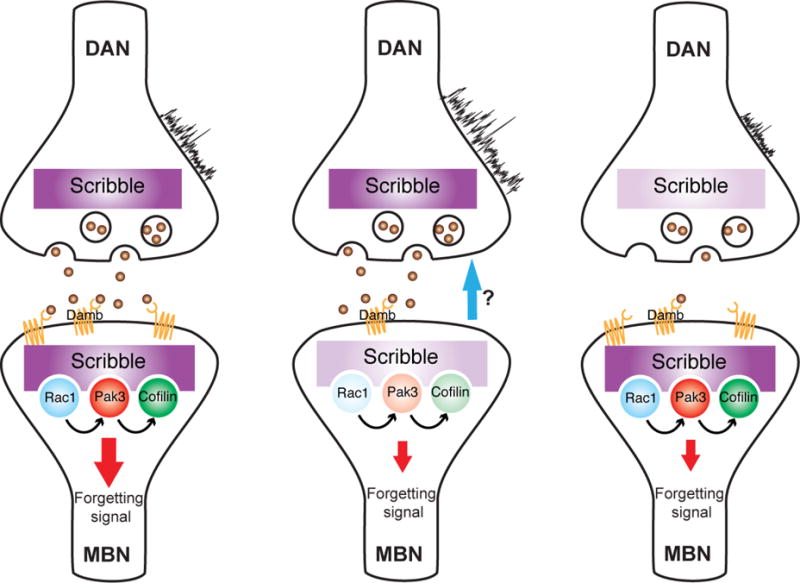

Figure 7 illustrates our model of Scrb function in active forgetting. Scrb is necessary in both DAn and MBn for normal propagation of the forgetting signal. In the wild type situation (Figure 7, left panel), ongoing activity in DAn, regulated by the behavioral state (Berry et al., 2015), initiates the forgetting signal to the MBn by activating the Damb receptor, which in turn, deploys the forgetting signalosome and the activation of Rac1, Pak3 and the phosphorylation of Cofilin in the MBn. This signaling complex regulates actin dynamics and produces cytoskeletal changes that emerge as forgetting (Shuai and Zhong, 2010). Reducing Scrb function in MBn impairs the forgetting signal postsynaptically (Figure 7 middle panel), by altering the abundance and efficacy of the forgetting signaling complex. Unexpectedly, we discovered a presynaptic increase of ongoing DAn activity when Scrb is KD in the MBn. How this occurs is not yet understood. Recent studies have identified the existence of many loops within the circuitry of MB (Aso et al., 2014). MB output neurons can be presynaptic to DAn, which in turn, are pre-synaptic to MB. Additionally, some MB output neurons also synapse back directly on other MBn axons (Aso et al., 2014). It is possible that these loops contribute to the regulation of DAn spontaneous activity by MB output. Other possibilities include the existence of bidirectional synapses between DAn and MB or a retroactive signal, similar to that reported at the neuromuscular junction (Davis, 2013). Normal Scrb expression is also required in DAn for normal memory loss (Figure 7, right panel). In this instance, Scrb is necessary for maintaining the ongoing activity of DAn, presumably by altering presynaptic release or by interfering postsynaptically with DAn stimulation by upstream neurons.

Figure 7. Model for the role of Scrb in forgetting.

Ongoing activity of DAn through the Damb receptor modulates the strength of the “forgetting signal” (red arrow) in the MBn. The Scrib protein scaffolds a signaling complex consisting of Rac1, Pak3 and Cofilin. Knocking down scrb in MBn impairs postsynaptic signaling of forgetting (middle panel). Knocking down scrb also increases ongoing DAn activity through a retroactive signal (blue arrow). Scrb is also required in the presynaptic compartment, e.g., in DAn for normal memory loss by maintaining the ongoing activity in these neurons (right panel).

We also show that Scrb slightly impairs acquisition when flies are trained with mild conditioning protocols i.e. low shock number. Similar mild learning defect was described for the forgetting mutant, damb (Berry et al., 2012). Whether the molecular machinery required for forgetting partially overlaps with the memory acquisition signaling remains to be elucidated. We proposed before (Berry et al, 2015) that the arousal coupled DA signal could regulate the plasticity of the memory system, making it malleable for memory updating so that current memories can be formed and old, unused memories can be forgotten. If this is true, it is conceivable that Scribble as part of this signaling pathway has some overlapping role between learning and forgetting events.

Synaptic scaffolding molecules, which by virtue of their ability to simultaneously bind multiple proteins, play crucial roles in orchestrating and integrating structural and functional molecular interactions in signaling systems. This magnifies their significance for understanding signaling processes. Here we provide evidence that Scrb, a scaffolding protein for synaptic molecules, is essential for the recently discovered process of active forgetting. We anticipate that other molecules besides Rac1, Pak1 and Cofilin will be found to interact with Scrb and participate in regulating the forgetting of memories. Whether these molecular components are disrupted in the pathologies of forgetting remains to be explored.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Drosophila husbandry

Flies were cultured on standard medium at room temperature. Crosses, unless otherwise stated, were kept at 25°C and 70% relative humidity with a 12 hr light-dark cycle. The gal4 drivers used in this study include nsyb-gal4, th-gal4 (Friggi-Grelin et al., 2003), c772-gal4, 238y-gal4 (Yang et al., 1995), gh146-gal4 (Stocker et al., 1997), NP2492-gal4 (Tanaka et al., 2008), VT64246-gal4 (Lee et al., 2011), R13F02-gal4 (Jenett et al., 2012), NP2631-gal4 (Tanaka et al., 2008), MZ604-gal4 (Ito et al., 1998), Or83b-gal4 (Wang et al., 2003), G0431-gal4 (Chen et al., 2012), c739-gal4 (Yang et al., 1995), c305a-gal4 (Krashes et al., 2007), 1471-gal4 (Isabel et al., 2004), c150-gal4 (Dubnau et al., 2003), c061-gal4 (Krashes et al., 2009) and NP5272-gal4 (Tanaka et al., 2008). We also employed the th-lexA driver described by Berry et al (2015). The uas-RNAi transgene stocks from the KK library (www.stockcenter.vdrc.at) include control line (60100), which contains the attP docking site without an RNAi insertion (hence same insertional modification as uas-RNAi lines), uas-scrbRNAi (100363), uas-scrbRNAi2 (105412), and from the GD library uas-scrbRNAi3 (27430). Additional uas transgene stocks included uas-dicer2, uas-GFP::CD8 (Lee and Luo, 1999), uas-rfp (Pramatarova et al., 2003), uas-g-camp3.0 (Tian et al., 2009), and uas-rac1V12 (Luo et al., 1994). The lexAop transgene stocks include lexAop-trpA1 (Burke et al., 2012), lexAop-tdTom (Yuan et al., 2011), lexAop-g-camp3.0 (Yao et al., 2012). Additional stocks employed include tub-gal80ts (McGuire et al., 2003), MB-gal80 (Krashes et al., 2007), scrb1 (Bilder, 2000; Bilder and Perrimon, 2000) and scrb::GFPCA07683 (Buszczak et al., 2007).

For the production of uas-damb lines, the dopamine 1-like receptor 2 isoform A cDNA (NM_170420.2) was amplified from pKS-damb (Han et al., 1996) with the following primer set: forward 5′-GGAATTGGGAATTCCTGAGTTGCAATGG-3′ and reverse 5′-AGAGGTACCCTCGAGTCACATGAGCGTCCGGT-3′. These primers included an EcoRI site located +15bp upstream of the damb start site and introduced a stop codon followed by an XhoI site downstream of the last coding nucleotide. The PCR product was digested with EcoRI and XhoI and ligated into the pUAST vector downstream of the Hsp70 minimal promoter and upstream of the SV40 terminator sequence. The construct was then used to generate flies used to overexpress the Damb receptor (Rainbow Transgenic Flies, Inc, Camarillo, CA).

After chromosome mapping, the behavior of flies expressing different uas-damb insertions was evaluated. We measured 3 min and 3 hr memory of adult flies expressing different uas-damb insertions in MBn using R13F02-gal4 and the TARGET system. Fly line uas-damb#3, inserted on the second chromosome, was used for further experiments since did not show a 3 min memory deficit when expressed in adult flies. In contrast 3 hr memory was impaired in these animals, suggesting an accelerated memory loss (Figure 4A). Additional lines were discarded from further analysis because they showed a 3 min memory phenotype. This difference may come from differences in expression levels that could lead to memory acquisition inhibition.

Behavior

We used 2 to 6 day old flies for all behavior experiments. Standard aversive olfactory conditioning experiments were performed as described (Beck et al., 2000). Briefly, a group of ~60 flies were loaded into a training tube where they received the following sequence of stimuli: 30s of air, 1 min of an odor paired with 12 pulses of 90V electric shock (CS+), 30 s of air, 1 min of a second odor with no electric shock pulses (CS−), and finally 30 s of air. We used 3-octanol (OCT) and 4-methylcyclohexanol (MCH) as standard odorants. Additional odorants where used for reversal and interference experiments (see below). To measure memory, we transferred the flies into a T-maze where they were allowed 2 min to choose between the two odors used for training. To test memory retention curves, we tapped the flies after conditioning back into food vials to be tested at later time points (1, 3, 6, 12 and 24h).

Acquisition curves were performed by training the flies with 1, 2, 3, 6 or 12 electric shock pulses evenly distributed over 1 min of the CS+ presentation. A second acquisition curve was obtained by training the flies with 12 electric shock pulses of different intensity (10, 20, 45 and 90V).

For cyclohexamide experiments, flies were fed with 35mM cyclohexamide (CXM), 5% glucose dissolved in 3% ethanol solution for 16 hr (overnight). Control flies were fed in 5% glucose dissolved in 3% ethanol. Flies were transferred to regular food vials 1 hr before conditioning. Memory was tested 24 hr after training.

Cold shock experiments were performed by transferring trained flies to cold glass vials (~0°C) 2 hr after training for 2 min duration. The flies were returned to food vial at 25°C and memory tested 3 hr after training. Flies were reared at either 18°C or 30°C for TARGET experiments. One-two day-old flies were transferred and kept at 30°C or 18°C for 4 days. Control flies were maintained at 18°C or 30°C throughout the experiment. For all conditions, flies were transferred to 25°C 1 hr prior to training and until the end of experiment.

Reversal learning experiments were performed by training flies with the standard conditioning protocol (CS+ = OCT, CS− = MCH; reciprocal CS+ = MCH, CS− = OCT) followed by 1 min of air and then the reverse odor-shock contingency (CS+=MCH, CS−=OCT; reciprocal CS+ = OCT, CS− = MCH). The memory test was performed immediately after reversal training. For reversal learning with third odor, flies were trained as described for reversal learning (CS+ = OCT, CS− = BEN; reciprocal CS+ = MCH, CS− = BEN) followed by 1 min of air and the reverse odor-shock contingency (CS+=BEN, CS−=OCT; reciprocal CS+ = BEN, CS− = MCH). The memory test was performed using the odor first use as CS+ and a third odor (i.e. OCT and MCH) not experienced during training.

For retroactive interference experiments, flies were trained using the standard conditioning protocol with OCT and MCH. Then flies were then re-trained 1.5 hr after the first training session with a second odor combination using benzaldehyde (BEN) and methylsalicylate (MES). The memory test was performed 3 hr after initial training using OCT and MCH. For proactive interference experiments, flies were trained using the standard conditioning protocol with BEN and MES, exposed to 1 min of air, and then retrained using OCT and MCH. The memory test was performed immediately after the second training session using OCT and MCH.

Flies were transferred to 23°C 1 hr before training for TrpA1 stimulation experiments. They were trained using the standard aversive protocol. At 1.5 hr after training, flies were transferred to 32°C for 5 min, and then returned to 23°C. Memory was measured at 3 hr after conditioning. Control flies were kept at 23°C throughout the experiment.

Drosophila sleep and activity were measured using the Drosophila Activity Monitoring System (Trikinetcs) as described previously (Shaw et al., 2000). In summary, flies were placed into individual 65 mm tubes and the activity was continuously monitored. Locomotor activity was measured in 1 min bins and sleep was defined as periods of quiescence lasting at least 5 m. Sleep in min/hr data was plotted as a function of zeitgeber time (ZT).

Functional imaging experiments

Spontaneous activity of DAn was recorded as previously reported (Berry et al., 2012). Briefly, a single fly was aspirated without anesthesia into a narrow slot, the width of a fly, in a custom-designed recording chamber. The head was immobilized by gluing the eyes to the chamber using myristic acid and the proboscis also fixed to reduce movements. A small, square section of dorsal cuticle was removed from the head to allow optical access to the brain. Fresh saline (103 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 5 mM HEPES, 1.5 mM CaCl2, MgCl2, 26 mM NaHCO3, 1 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM trehalose, 7 mM sucrose, and 10 mM glucose [pH 7.2]) was perfused immediately across the brain to prevent desiccation and ensure the health of the fly. Using a 25× water-immersion objective and a Leica TCS SP5 II confocal microscope with a 488 nm argon laser, we imaged the TH neurons spontaneous activity. We used one PMT channel (510–550 nm) to detect G-CaMP3.0 fluorescence and a second PMT channel to detect either RFP (610–700 nm) or TdTomato (600–700 nm) fluorescence. Recordings were collected at 2 frames/sec during a 10 min recording session. The activity per second was calculated for each recording using algorithms previously described (Berry et al., 2012).

Antibody production

Antisera to Scrb were obtained by immunizing rabbits with four synthetic peptides of Scrb. The peptide sequences were REVTRLIGHPVFSED, REYRGPLEPPTSPRS, DHEEDERLRQDFDV and KSPSEHHEQDKIQKT. Rabbits were immunized with a mixture of the four peptides together with Complete Freund’s adjuvant followed by two boost injections on days 14 and 28 with Incomplete Freund’s adjuvant. The serum was tested by ELISA against the synthetic peptides and by competition assays using western blotting of a recombinant Scrb polypeptide. The antisera against peptides REYRGPLEPPTSPRS and DHEEDERLRQDFDV proved to be the most robust, so that these antisera were then purified by affinity chromatography using these peptides.

Immunostaining

Whole brains were isolated and processed with minor modifications of those described (Jenett et al., 2012). Brains were first incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti-GFP (1:1000, Life Technologies cat# A11122, RRID: AB_10073917) or anti-Scrb (1:50, RRID: AB_2571725) and mouse monoclonal anti-nc82 (1:50, University of Iowa, DSHB, RRID: AB_2314866) followed by incubation with anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (1:800, Life Technologies Cat# A11008, RRID: AB_143165) and anti-mouse IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 633 (1:400, Life Technologies Cat# A21052, RRID: AB_1414589). Images were collected using a 10× dry objective and a Leica TCS SP5 II confocal microscope with 488 and 633 nm lasers. The step size for z-stacks was 1 μm with images collected at 512 × 512 pixel resolution. To quantify the expression of Scrb in MB lobes from flies expressing scrbRNAi using the MB R13F04-gal4 driver, an ROI was drawn to measure mean fluorescence intensity across the multiple sub stacks containing γ lobes. An ROI from the antenna-mechanosensory and motor center (AMMC) that showed no anti-Scrb signal was used for background subtraction. Data was then normalized to control brains containing only gal4 driver.

Western blots

Western blots were used to measure Scrb protein in flies expressing different RNAi using nsyb-gal4 driver in the scrb::GFPCA07683 background. These gene-trap flies express endogenous Scrb::GFP as a fusion protein using the endogenous scrb promoter/enhancer functions. Protein extracts were obtained by homogenizing 50 fly heads in RIPA lysis buffer, pH 7.5 (20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 μg/ml leupeptin). The equivalent of 3 fly heads was then loaded in each lane for SDS-PAGE. After transfer, PVDF membranes were blocked for 2 hr with 5% skim milk, 1% BSA in wash buffer (Tris buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20). The membrane was then washed six times for 10 min, and then incubated with primary antibody (anti-GFP, 1:1000, RRID: AB_439690; anti-Scrb, 1:1000 RRID: AB_2571725; or anti-GAPDH, 1:1000, RRID: AB_1080976) overnight at 4°C. After washing six more times, the membrane was incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 hr (1:5000, Jackson Immunoresearch Cat# 111-035-144, RRID: AB_2307391). After 6 more wash cycles, the membrane was incubated with substrate, Advansta WesternBright Quantum (Cat# K-12042-D10), and the intensity of the resulting bands was quantified using the ImageJ software gel analysis tool. Relative expression was then calculated to the respective genetic control.

Immunoprecipitation

Immunoprecipitation experiments were performed to identify proteins that physically interact with Scrb. Briefly, three thousand Scrb::GFPCA07683 fly heads were lysed in 1.5 ml of RIPA buffer (Cell Signalling Technology) supplemented with cocktails of protease and phosphatase Inhibitors (Roche). The samples were pre-clear by incubation with Sepharose beads (Sigma-Aldrich) and protein A beads pre-conjugated with rabbit IgG (CST 2729S) in 1 ml of RIPA buffer for 4 hr at 4°C. After pre-clearing, the samples were incubated overnight at 4°C with 100 μl slurry of anti-GFP-conjugated Sepharose beads (Abcam ab69314) or unconjugated Sepharose beads. The beads were washed and protein complexes eluted with 2× Laemmli Sample Buffer (BioRad). SDS-PAGE was performed using a 4–15% gradient gel and the gel proteins transferred to PVDF membrane for immunoblotting.

Immunoprecipitation experiments utilizing anti-Rac1 were performed with wcs10 flies as described above except that the lysates were incubated with 100 μl slurry of protein A agarose beads plus 2.5 μg of anti-Rac1 mouse monoclonal antibody Control lysates were incubated with beads alone.

Immunoblots were performed as described above. The primary antibodies employed were: rabbit anti-GFP, 1:1000 (Sigma cat# G1544, RRID: AB_439690); monoclonal anti-Rac1, 1:500 (BD Transduction Labs cat# 610650, RRID: AB_397977); monoclonal anti-Pak3, 1:1000 (kindly donated by Nicholas Harden, RRID: AB_2566940); rabbit anti-Cofilin, 1:1000 (Signalway cat# 40769, RRID: AB_2571724); rabbit anti-pCofilin, 1:1000 (Signalway cat# 11139, RRID: AB_895208); rabbit anti-Scrb, 1:1000 (generated here, RRID: AB_2571725).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from 30 fly heads using Qiagen Qiashredder columns and the RNeasy lipid tissue kit (cat No. 74804). One hundred nanograms of RNA was then used for synthesis of cDNA using random hexamers and the SuperScript III first strand synthesis kit (Invitrogen, cat no. 18080-51). Real time RT-PCR was then performed using an Applied Biosystems quantitative assay for scrb (dm02151118_g1). The expression of the housekeeping gene gapdh (dm01843776_s1) was used to normalize expression. Relative expression was then calculated to the respective genetic control.

Statistical analyses

Statistics were performed using Prism 5 (Graphpad). All tests were two tailed and confidence levels were set at α = 0.05. The figure legends present the p values and comparisons made for each experiment. Unless otherwise stated, non-parametric tests were used for in vivo imaging data and DAM system monitoring, while parametric tests were used for olfactory memory comparisons as PI values are normally distributed (Walkinshaw et al., 2015).

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Scribble is a Drosophila memory suppressor gene

The gene is expressed and functions in mushroom body and dopaminergic neurons

It is necessary for normal active forgetting

It regulates memory loss by scaffolding a forgetting signalosome

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants 2R37NS19904 and 2R01NS05235 from the NINDS to R.L.D. We thank Dr. D. Bilder for providing an anti-Scrb antibody that was used in pilot experiments. We thank Dr. N. Harden for providing anti-Pak3 antibody.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental information includes 5 figures, two videos, and one table.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

The project was conceived of by I.C.S. and R.L.D. I.C-S. planned all experiments, performed all olfactory memory assays and in vivo imaging experiments, analyzed the data. M. C. performed all immunostaining, immunoprecipitation and western blotting experiments. C.M generated the uas-damb lines and genotyped Drosophila stocks. R.L.D. oversaw the execution of the project and contributed to the interpretation of the data. I.C-S. and R.L.D. wrote initial drafts of the manuscript; all authors contributed comments and edits to produce the final version.

References

- Anderson MC. Rethinking interference theory: Executive control and the mechanisms of forgetting. J Mem Lang. 2003;49:415–445. [Google Scholar]

- Akers KG, Martinez-Canabal A, Restivo L, Yiu AP, De Cristofaro A, Hsiang HL, Wheeler AL, Guskjolen A, Niibori Y, Shoji H, et al. Hippocampal neurogenesis regulates forgetting during adulthood and infancy. Science. 2014;344:598–602. doi: 10.1126/science.1248903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahri S, Wang S, Conder R, Choy J, Vlachos S, Dong K, Merino C, Sigrist S, Molnar C, Yang X, et al. The leading edge during dorsal closure as a model for epithelial plasticity: Pak is required for recruitment of the Scribble complex and septate junction formation. Development. 2010;137:2023–2032. doi: 10.1242/dev.045088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck CD, Schroeder B, Davis RL. Learning performance of normal and mutant Drosophila after repeated conditioning trials with discrete stimuli. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2944–2953. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-08-02944.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry J, Cervantes-Sandoval I, Chakraborty M, Davis R. Sleep facilitates memory retention by blocking dopamine neuron mediated forgetting. Cell. 2015;161:1656–1667. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry J, Cervantes-Sandoval I, Nicholas E, Davis R. Dopamine is required for learning and forgetting in Drosophila. Neuron. 2012;74:530–572. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilder D. Cooperative Regulation of Cell Polarity and Growth by Drosophila Tumor Suppressors. Science. 2000;289:113–116. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5476.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilder D, Perrimon N. Localization of apical epithelial determinants by the basolateral PDZ protein Scribble. Nature. 2000;403:676–680. doi: 10.1038/35001108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke CJ, Huetteroth W, Owald D, Perisse E, Krashes MJ, Das G, Gohl D, Silies M, Certel S, Waddell S. Layered reward signalling through octopamine and dopamine in Drosophila. Nature. 2012;492:433–437. doi: 10.1038/nature11614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buszczak M, Paterno S, Lighthouse D, Bachman J, Planck J, Owen S, Skora AD, Nystul TG, Ohlstein B, Allen A, et al. The carnegie protein trap library: a versatile tool for Drosophila developmental studies. Genetics. 2007;175:1505–1531. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.065961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CC, Wu JK, Lin HW, Pai TP, Fu TF, Wu CL, Tully T, Chiang AS. Visualizing long-term memory formation in two neurons of the Drosophila brain. Science. 2012;335:678–685. doi: 10.1126/science.1212735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden JR, Skoulakis EM, Han KA, Kalderon D, Davis RL. Tripartite mushroom body architecture revealed by antigenic markers. Learn Mem. 1997;5:38–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GW. Homeostatic signaling and the stabilization of neural function. Neuron. 2013;80:718–728. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubnau J, Chiang AS, Grady L, Barditch J, Gossweiler S, McNeil J, Smith P, Buldoc F, Scott R, Certa U, et al. The staufen/pumilio pathway is involved in Drosophila long-term memory. Curr Biol. 2003;13:286–296. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00064-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friggi-Grelin F, Coulom H, Meller M, Gomez D, Hirsh J, Birman S. Targeted gene expression in Drosophila dopaminergic cells using regulatory sequences from tyrosine hydroxylase. J Neurobiol. 2003;54:618–627. doi: 10.1002/neu.10185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly I, Mackay TF, Anholt RR. Scribble is essential for olfactory behavior in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2003;164:1447–1457. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.4.1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genoux D, Haditsch U, Knobloch M, Michalon A, Storm D, Mansuy IM. Protein phosphatase 1 is a molecular constraint on learning and memory. Nature. 2002;418:970–975. doi: 10.1038/nature00928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadziselimovic N, Vukojevic V, Peter F, Milnik A, Fastenrath M, Fenyves BG, Hieber P, Demougin P, Vogler C, de Quervain DJ, Papassotiropoulos A, Stetak A. Forgetting Is Regulated via Musashi-Mediated Translational Control of the Arp2/3 Complex. Cell. 2014;156:1153–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han KA, Millar NS, Grotewiel MS, Davis RL. DAMB, a novel dopamine receptor expressed specifically in Drosophila mushroom bodies. Neuron. 1996;16:1127–1135. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80139-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isabel G, Pascual A, Preat T. Exclusive consolidated memory phases in Drosophila. Science. 2004;304:1024–1027. doi: 10.1126/science.1094932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Suzuki K, Estes P, Ramaswami M, Yamamoto D, Strausfeld NJ. The organization of extrinsic neurons and their implications in the functional roles of the mushroom bodies in Drosophila melanogaster Meigen. Learn Mem. 1998;5:52–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenett A, Rubin GM, Ngo TT, Shepherd D, Murphy C, Dionne H, Pfeiffer BD, Cavallaro A, Hall D, Jeter J, et al. A GAL4-driver line resource for Drosophila neurobiology. Cell Rep. 2012;2:991–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krashes MJ, DasGupta S, Vreede A, White B, Armstrong JD, Waddell S. A neural circuit mechanism integrating motivational state with memory expression in Drosophila. Cell. 2009;139:416–427. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krashes MJ, Keene AC, Leung B, Armstrong JD, Waddell S. Sequential use of mushroom body neuron subsets during Drosophila odor memory processing. Neuron. 2007;53:103–115. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee PT, Lin HW, Chang YH, Fu TF, Dubnau J, Hirsh J, Lee T, Chiang AS. Serotonin-mushroom body circuit modulating the formation of anesthesia-resistant memory in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:13794–13799. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019483108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T, Luo L. Mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker for studies of gene function in neuronal morphogenesis. Neuron. 1999;22:451–461. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80701-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo L, Liao YJ, Jan LY, Jan YN. Distinct morphogenetic functions of similar small GTPases: Drosophila Drac1 is involved in axonal outgrowth and myoblast fusion. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1787–1802. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.15.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew D, Gramates LS, Packard M, Thomas U, Bilder D, Perrimon N, Gorczyca M, Budnik V. Recruitment of scribble to the synaptic scaffolding complex requires GUK-holder, a novel DLG binding protein. Curr Biol. 2002;12:531–539. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00758-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Z, Davis RL. Eight different types of dopaminergic neurons innervate the Drosophila mushroom body neuropil: anatomical and physiological heterogeneity. Front Neural Circuits. 2009;3:5. doi: 10.3389/neuro.04.005.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire SE, Le PT, Osborn AJ, Matsumoto K, Davis RL. Spatiotemporal rescue of memory dysfunction in Drosophila. Science. 2003;302:1765–1768. doi: 10.1126/science.1089035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigerius M, Naveed A, Wessam M, Magnus J. Scribble controls NGF-mediated neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells. Eur J Cell Biol. 2013;92:213–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau MM, Piguel N, Papouin T, Koehl M, Durand CM, Rubio ME, Loll F, Richard EM, Mazzocco C, Racca C, et al. The planar polarity protein Scribble1 is essential for neuronal plasticity and brain function. J Neurosci. 2010;30:9738–9752. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6007-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nola S, Sebbagh M, Marchetto S, Osmani N, Nourry C, Audebert S, Navarro C, Rachel R, Montcouquiol M, Sans N, et al. Scrib regulates PAK activity during the cell migration process. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:3552–3565. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pramatarova A, Ochalski PG, Chen K, Gropman A, Myers S, Min KT, Howell BW. Nck beta interacts with tyrosine-phosphorylated disabled 1 and redistributes in Reelin-stimulated neurons. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:7210–7221. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.20.7210-7221.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche JP, Packard MC, Moeckel-Cole S, Budnik V. Regulation of synaptic plasticity and synaptic vesicle dynamics by the PDZ protein Scribble. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6471–6479. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06471.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachser RM, Santana F, Crestani AP, Lunardi P, Pedraza LK, Quillfeldt JA, Hardt O, de Oliveira Alvares L. Forgetting of long-term memory requires activation of NMDA receptors, L-type voltage-dependent Ca(2+) channels, and calcineurin. Scientific reports. 2016;6:22771. doi: 10.1038/srep22771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw PJ, Cirelli C, Greenspan RJ, Tononi G. Correlates of sleep and waking in Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 2000;287:1834–1837. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuai Y, Lu B, Hu Y, Wang L, Sun K, Zhong Y. Forgetting is regulated through Rac activity in Drosophila. Cell. 2010;140:579–589. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuai Y, Zhong Y. Forgetting and small G protein Rac. Protein Cell. 2010;1:503–506. doi: 10.1007/s13238-010-0077-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker RF, Heimbeck G, Gendre N, de Belle JS. Neuroblast ablation in Drosophila P[GAL4] lines reveals origins of olfactory interneurons. J Neurobiol. 1997;32:443–456. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(199705)32:5<443::aid-neu1>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storm BC. The Benefit of Forgetting in Thinking and Remembering. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2011;20:291–295. [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Aiga M, Yoshida E, Humbert PO, Bamji SX. Scribble interacts with beta-catenin to localize synaptic vesicles to synapses. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:3390–3400. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-12-1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka NK, Tanimoto H, Ito K. Neuronal assemblies of the Drosophila mushroom body. J Comp Neurol. 2008;508:711–755. doi: 10.1002/cne.21692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian L, Hires SA, Mao T, Huber D, Chiappe ME, Chalasani SH, Petreanu L, Akerboom J, McKinney SA, Schreiter ER, et al. Imaging neural activity in worms, flies and mice with improved GCaMP calcium indicators. Nat Methods. 2009;6:875–881. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomchik SM, Davis RL. Dynamics of learning-related cAMP signaling and stimulus integration in the Drosophila olfactory pathway. Neuron. 2009;64:510–521. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tully T, Preat T, Boynton SC, Del Vecchio M. Genetic dissection of consolidated memory in Drosophila. Cell. 1994;79:35–47. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90398-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walkinshaw E, Gai Y, Farkas C, Richter D, Nicholas E, Keleman K, Davis RL. Identification of Genes that Promote or Inhibit Olfactory Memory Formation in Drosophila. Genetics. 2015;199:1173–1182. doi: 10.1534/genetics.114.173575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JW, Wong AM, Flores J, Vosshall LB, Axel R. Two-photon calcium imaging reveals an odor-evoked map of activity in the fly brain. Cell. 2003;112:271–282. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wixted JT. The psychology and neuroscience of forgetting. Annu Rev Psychol. 2004;55:235–269. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang MY, Armstrong JD, Vilinsky I, Strausfeld NJ, Kaiser K. Subdivision of the Drosophila mushroom bodies by enhancer-trap expression patterns. Neuron. 1995;15:45–54. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Z, Macara AM, Lelito KR, Minosyan TY, Shafer OT. Analysis of functional neuronal connectivity in the Drosophila brain. J Neurophysiol. 2012;108:684–696. doi: 10.1152/jn.00110.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu D, Akalal DB, Davis RL. Drosophila alpha/beta mushroom body neurons form a branch-specific, long-term cellular memory trace after spaced olfactory conditioning. Neuron. 2006;52:845–855. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Q, Xiang Y, Yan Z, Han C, Jan LY, Jan YN. Light-induced structural and functional plasticity in Drosophila larval visual system. Science. 2011;333:1458–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.1207121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan L, Rosenberg A, Bergami KC, Yu M, Xuan Z, Jaffe AB, Allred C, Muthuswamy SK. Deregulation of scribble promotes mammary tumorigenesis and reveals a role for cell polarity in carcinoma. Cell. 2008;135:865–878. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.