Abstract

In this study, low-density polyethylene (LDPE) containing oxygen scavenger based on sodium ascorbate (SA) and ethylene vinyl alcohol (EVOH) at 5, 10 and 15 % concentrations were produced through extrusion method. In addition, the effect of size of SA, thickness LDPE (7.5, 15, 30 and 45 μm), and number of layers (monolayer, two-layers, three-layers and four-layers) were investigated. Oxygen and water vapor permeability, tensile stress, SA migration and antioxidant activity, thermal stability, scan electron microscopy (SEM), and FT-IR of the films were measured. Moreover, the performance of produced films to prevent of oxidation of packaged peanuts during storage at 40 °C was studied. The results revealed that the active films containing SA (especially at 10 % SA) present suitable performance and features to increase the shelf-life of peanuts.

Keywords: Low-density polyethylene, Sodium ascorbate, Ethylene vinyl alcohol, Active film, Oxygen scavenger

Introduction

Peanut is belonged nuts and considered as a valuable food since ancient times. Nevertheless, their high content of unsaturated fatty acids makes them prone to oxidative rancidity leading to the quality deterioration, if stored at unsuitable conditions or for too long (O’keefe et al. 1993). This is a main issue of economic concern to the food industry, both from the off-flavor development and the formation of toxic products from lipid oxidation that may have detrimental health effects (Lopez-de-Dicastillo et al. 2013).

The packaging system is very important to prevent effectively the quality deterioration. Eliminating oxygen initially present within the package headspace and the food itself, as well as eliminating oxygen that permeate through even high-barrier polymeric packaging or coatings are characteristics of an appropriate packaging system (Barbosa-Pereira et al. 2013). However, inactive polymeric packaging or coating does not prevent adverse effects of headspace or food-dissolved oxygen or penetration of oxygen over a long period. Modified atmosphere packaging techniques are usually time consuming and are not forever convenient, effective, or economical, particularly as oxygen levels below 0.5 % are desired (Brody et al. 2008; Janjarasskul et al. 2011). Oxygen scavengers can be used in packaging technology as active substances that eliminate any food-absorbed oxygen or residual headspace and continuously absorb any permeating oxygen (Suppakul et al. 2003; Janjarasskul et al. 2011). Thus, using of this technique in the packaging improve food quality and shelf life. The main issue of this approach is potential migration of inorganic active compound into food product, as well as non-recyclability. However, these disadvantages are not observed for an edible, oxygen-absorbing film (Byun et al. 2010).

LDPE (Low-density polyethylene) films, like all polymer materials, allow some penetration of oxygen that can eventually produce rancid foods. LDPE film, with an oxygen-scavenging activity added by incorporation of sodium ascorbic (SA) and ethylene vinyl alcohol (EVOH), when used in combination with oxygen-barrier packaging, can be an optional method to omit oxygen existent in the package headspace. Other benefits of this alternative technique are: (1) reduced packaging costs by omitting need for vacuum packaging; (2) omitting the safety concern about migration of inorganic scavengers or casual consumption of oxygen-absorbing sachets; and (3) enhanced recyclability.

Active packaging containing oxygen scavengers was used commercially with a wide range of foods such as fish (Barbosa-Pereira et al. 2013), roasted peanuts (Han et al. 2008), flour tortillas (Antunez et al. 2012), roasted sunflower seeds and walnuts (Mu et al. 2013), raw whole unpeeled almond kernels (Mexis and Kontominas 2010), and ham (Andersen and Rasmussen 1992).

The present research was based on the hypothesis that SA could be incorporated and functions as an oxygen scavenger in LDPE-based films and that the incorporation of SA would effect on the mechanical, barrier, and thermal properties of LDPE-based films due to the effect of SA on its structure. Therefore, the objectives of this paper were to (1) assess the oxygen-scavenging potential of an edible LDPE film incorporating SA and EVOH; (2) evaluate the effects of incorporating SA and EVOH into LDPE films on mechanical, oxygen-barrier, and thermal properties; and (3) using these active packaging to increase the shelf-life peanuts.

Materials and methods

Materials

LDPE 0200 grade, EVOH, maleic acid-grafted LDPE were obtained from National Petrochemical Company of Iran. SA was prepared from Dai Jung Company (South Korea). Peanut was purchased from local market of Mashhad. All solvents and chemicals used in this study were of analytical reagent grade and supplied by Merck Company.

Films productions

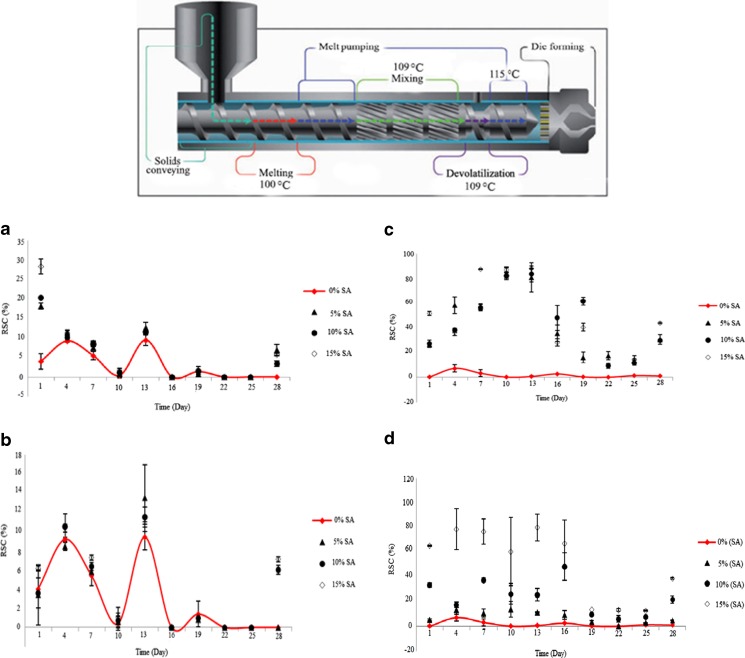

At the first, LDPE and EVOH polymers were incubated at 80 °C for 1 h to eliminate moisture. In order to produce active films, SA (in powder form) and/or EVOH were mixed with LDPE at 5, 10 and 15 % ratios. The film produced from alone LDPE was considered as control sample. Film production process was performed using a parallel two-screw extruder (Model ZSK, Germany) with a screw diameter (D) 12 mm, screw length (L/D) 24 mm, die width 200 mm, and thickness of 0.250 mm. The temperature profile from the feed to die was 100, 109, 109 and 115 °C (Fig. 1). Rotation speed of screw was 40 rpm. The exorcised from extruder was cooled to 10 °C in a pool of cold water, and then obtained strip was powdered by grinding machine. The granules incubated at 80 °C for 2 h to eliminate moisture. In the next step of film production, the produced granules were transferred into film blender machine (Brabender, Germany). The temperature profile from the feed to die in this machine was 100, 109, 109 and 115 °C; as well as, the rotation speed of screw was 47.2 rpm. In the next step, film was stretched and winded by using stretch and winder machine at 27 m per min round and 47.2 rpm rotation. The produced films packaged under vacuum condition and stored in refrigerator until testing. In addition to produce of the active films, films with different thickness (15, 30 and 45 μm) and multi-layer films (two-layer, three-layer and four-layer) were prepared from LDPE.

Fig. 1.

The temperature profile for extruder during the film producing. a: DPPH radical inhibitory percentage in ethanolic food model containing SA-LDPE film. b: DPPH radical inhibitory percentage in ethanolic food model containing NSA-LDPE film. c: DPPH radical inhibitory percentage in aqueous food model containing SA-LDPE film. d: DPPH radical inhibitory percentage in aqueous food model containing NSA-LDPE film

Peanut packaging

Packages with dimensions of 10 × 15 were prepared from the produced films in order to pack peanuts (100 g). The packages were sewn by using a domestic heating sewing machine with single-wire element (Vacupack 383 model, KPUPS Company).

Packaging film tests

Migration

Migration rate of specific compound in different food environments is usually measured using stimulant models. In this study, mixture of ethanol and distilled water upon ratios of 95:5 and 10:90 were used for simulation of fat and aquatic environments, respectively. The migration tests including 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), ABTS, and ascorbate were used for 1 month and 3-day intervals (Lopez-de-Dicastillo et al. 2013).

DPPH

Radical scavenging capacity (RSC) measurement method was used with DPPH to determine antioxidant activity of the produced films. RSC% was calculated by following formula (Yolmeh et al. 2014):

where, Abs of sample and control are absorbance values of the sample and control at 517 nm, respectively.

ABTS

This test was carried out according to method described by Calatayud et al. (2013), and inhibitory percentage was calculated giving following formula:

where, I, Abs sample, and Abs control are inhibitory percentage, absorbance values of the sample and control, respectively.

Ascorbate

Migration of SA from film to the model solution was measured by reduction of 2,6-dichlorophenol indophenol and the following formula. The compound is reduced and its color change to pink-yellow by SA (Yolmeh and Najafzadeh 2014).

Water vapor permeability (WVP)

WVP was measured giving the ASTM E96 (1995) method and the following formula:

where x (mm), P, and WVTR are thickness of film, vapor pressure of pure water at 25 °C, and WVP rate, respectively.

Oxygen transmission rate (OTR)

OTR of produced active films was measured giving the method described by Ramos et al. (2012) and using gas permeability tester machine (Brugger 219, Germany).

Determining surface microstructure

Images were taken from surface of produced films coated with gold at ×500 and ×300 magnifications by scanning electronic microscopy (SEM) (Cambriidge S360, US) (Ramos et al. 2012).

Tensile measurement

Tensile of produced films was measured according to the method depicted by Byun et al. (2010) and using tensile tester (Cometech, QC-508B1, Taiwan).

Colorimetry

The color properties were evaluated as the L* (lightness), a* (Red-green), and b* (yellow-blue) values by hunterlab (colorflex, US). In addition, the general colorimetric difference (ΔE) was calculated by the below formula (Zahedi and Mazaheri-Tehrani 2012):

where, L0, a0, and b0 values are the color properties of pure LDPE.

Thermal analysis

The thermo gravimetric analysis (TGA) method and BAHR device (STA 503, Germany) were used to thermal analysis of the samples. Briefly, an amount of the sample (13 mg) was heated from 0 to 400 °C upon temperature increasing rate of 5 °C per 1 min under atmospheric environment.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

This test was performed giving Iranian National Standard method (2008a, b). Briefly, to evaluate releasing SA from matrix of the polymer to the models, some the active film containing 10 % SA on the first and the thirteenth days were removed from the model solutions and after drying, were tested under FTIR at wavenumbers of 400 to 4000 cm−1 using Shimadzu-4300 FTIR Spectromphotoeter.

Packaged peanut analysis

Peroxide value (PV)

The spectrophotometric method of the International Dairy Federation as described by Shantha and Decker was used to determine the peroxide value (PV) (Shantha and Decker 1994).

Conjugated diene value (CDV)

The conjugated diene value (CDV) was spectrophotometrically measured at 234 nm. The oil samples were diluted 1: 600 with hexane. An extinction coefficient of 29,000 mol/ L was utilized to quantify the concentration of conjugated dienes formed during oxidation. HPLC-grade hexane was used as blank (Saguy et al. 1996).

Thiobarbitoric Acid (TBA)

The method described by Prnbylski et al. (1989) was used to measure TBA value of the samples. The absorbance was measured at 532 nm using Shimadzu UV–VIS spectrophotometer and the TBA value was measured as mg malondialdehyde/kg sample. A standard curve was ploted using 1,1,3,3-tetraethoxypropane reagent for each replication.

Microbial tests

Total bacterial count

The ISO 7218 standard was used to total bacterial count. The samples were plated in nutrient agar (NA) and incubated at 30 °C for 24 h. After this period, colonies were counted.

Total mold and yeast count

Giving Iranian national standard, The sample plated in potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium and incubated at 25 °C for 3 to 7 days, and after this period colonies were counted (Iranian national standards, standard NO. 10899.1, 2007).

Statistical analysis

In the present study, full-randomized design and repeated measures method were used to comparing physicochemical properties of the produced films and evaluation of peanut shelf life, respectively. All experiments were performed at triplicate, and data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA). ANOVA and regression analyses were carried out according to Minitab 16 software. Significant differences between means were determined by Duncan’s multiple range tests; p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results and discussion

Migration

Giving the Fig. 1a, the highest RSC was observed for SA-LDPE film with 15 % SA at the first day of the test. However, the maximum release of SA nanoparticles into ethanolic food model was observed at 13th day of the storage period (Fig. 1b). In addition, the highest RSC for active films containing nanoparticle was measured about 11 to 13 %, which was less compared to SA-LDPE films. This implicates that the nanoparticles were strongly bonded to LDPE; so this particles slower migrate into the food model compared to natural SA particles. In the aqueous food model, SA had a high solubility and more quickly migrated into the model. Therefore, the RSC was more than ethanolic food model. The highest RSC for SA-LDPE active films was observed at the 7th to 13th day of the storage period; but this value for nanosodium ascorbic-LDPE (NSA-LDPE) was measured 85 % at 13th day of the storage period (Fig. 1c and d).

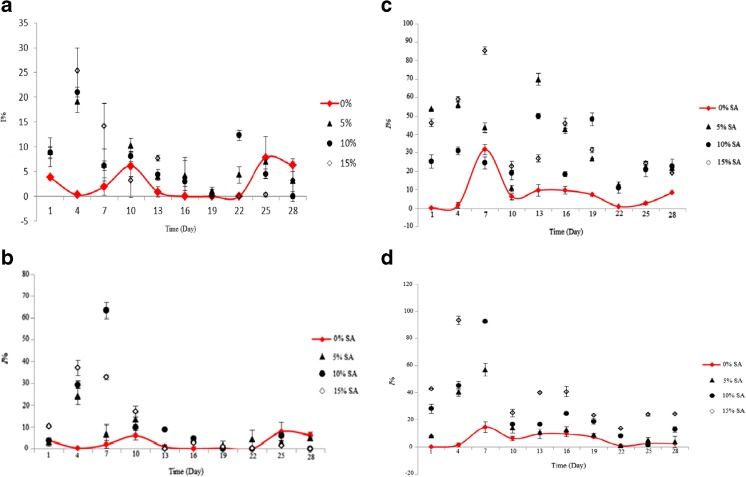

The maximum I% in the ethanolic food model containing active SA-LDPE film was observed at 15 % SA and after 4 day of storing (Fig. 2a). However, after 7 days of storing, large amounts of SA nanoparticles of active NSA-LDPE migrated from the film into the food model, so that I% in ethanolic food model reached to more than 63 % (Fig. 2b). Amount of migration of SA particles and nanoparticles into aqueous food model was more compared to the ethanolic food model, as is obvious in Fig. 2c and d. This is due to a higher affinity of SA to model liquid food because of the nature of this hydrophilic compound. I% in the aqueous food model containing SA-LDPE active film with 15 % SA was measured 85.32 after 7 day.

Fig. 2.

a: ABTS radical inhibitory percentage in ethanolic food model containing SA-LDPE film. b: ABTS radical inhibitory percentage in ethanolic food model containing NSA-LDPE film. c: ABTS radical inhibitory percentage in aqueous food model containing SA-LDPE film. d: ABTS radical inhibitory percentage in aqueous food model containing NSA-LDPE film

Giving Fig. 3a, release of SA for LDPE film without adding SA at 19th day of storage period was measured 15 %. This is probably due to use compounds derived from ascorbic acid with hydrophobic properties in the initial formulation of the base LDPE film, which producers used during construction. Similarly, the maximum release of SA for SA-LDPE and NSA-LDPE films with 5 and 10 % SA were observed at 19th day of storage period (Fig. 3a and b). No release of SA was observed for LDPE without SA into the aqueous food model. However, 21 % SA (at 19th day of storage period) and 24 % SA (at 7th day of storage period) was released from SA-LDPE and NSA-LDPE films, respectively, with 5 % SA into the aqueous food model (Fig. 3c and d). As an interesting result, no significant effect of SA nanoparticle concentration on release of SA was observed.

Fig. 3.

a: Release of SA in ethanolic food model containing SA-LDPE film. b: Release of SA in ethanolic food model containing NSA-LDPE film. c: Release of SA in aqueous food model containing SA-LDPE film. d: Release of SA in aqueous food model containing NSA-LDPE film

López-de-Dicastillo et al. (2011) reported that gallic acid and different catechins are the main releasing compound in aqueous and ethanolic food models, respectively. As well as, they showed that active packaging films based on ethylene vinyl alcohol (EVOH) copolymer have more antioxidant activity in aqueous food model. Pereira de Abreu et al. (2012) observed that migration of barley husk extract in LDPE film to isooctane and aqueous food models was negligible. Colín-Chávez et al. (2013) reported that diffusion of natural astaxanthin from polyethylene active packaging films into a fatty food stimulant at 23, 30 and 40 °C were 59.62 % (after 190.5 h), 93.81 % (after 53.38 h), and 97.95 % (after 12 h), respectively. However, the initial amount of astaxanthin remained same after 27.5 h and at 10 °C.

Water vapor permeability (WVP)

According to Table 1, as it is expected, WVP value was low for films based LDPE. As well as, this value was increased by adding SA compared to the film without antioxidant. Similarly, Byun et al. (2010) observed that WVP value of polylactic acid film containing BHT and polyethylene glycol was more than polylactic acid film without antioxidant. They reported that this fact is probably due to high free volume of film containing antioxidant through plasticizer effect of combination of polyethylene glycol and water (Byun et al. 2010).

Table 1.

Water vapor permeability (WVP) values of different fims

| LDPE | Concentration/Thickness/Number of film layers | WVP value (gmm/m2SKpa) 1.961 × 10−5 |

|---|---|---|

| 5 % | 3.225 × 10−5 | |

| SA-LDPE | 10 % | 2.050 × 10−5 |

| 15 % | 2.451 × 10−5 | |

| 5 % | 2.005 × 10−5 | |

| NSA-LDPE | 10 % | 1.472 × 10−5 |

| 15 % | 2.157 × 10−5 | |

| 5 % | 1.738 × 10−5 | |

| EVOH-LDPE | 10 % | 2.247 × 10−5 |

| 15 % | 1.872 × 10−5 | |

| 15 | 7.234 × 10−5 | |

| LDPE | 30 | 3.486 × 10−5 |

| 45 | 1.283 × 10−5 | |

| 2 L | 1.919 × 10−5 | |

| LDPE | 3 L | 2.117 × 10−5 |

| 4 L | 3.142 × 10−5 |

Oxygen transmission rate (OTR)

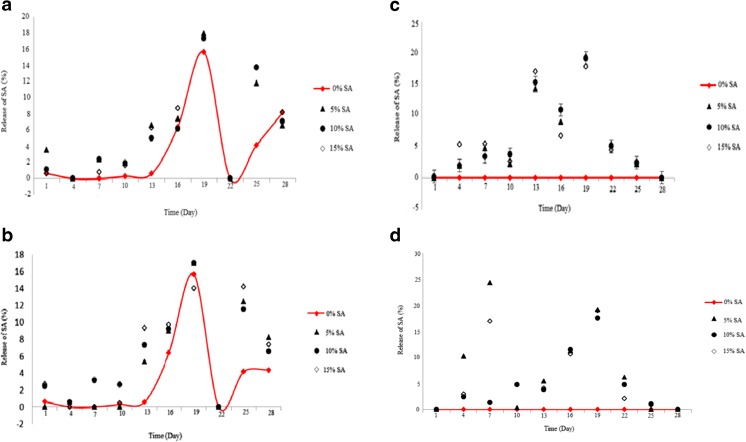

Giving Fig. 4a, OTR value was significantly decreased by adding SA to pure LDPE film (P < 0.05). At 10 and 15 % concentrations of SA, OTR value was more in NSA-LDPE compared to SA-LDPE, which this imples that decreasing particle size of SA at high concentrations leads to increase significantly the OTR value (P < 0.05). On other hand, adding EVOH polymer not only improved the oxygen permeability but also increased the OTR value. The highest and lowest the OTR value were measured for EVOH-LDPE film with 15 % SA (76 % increasing compared to the control) and SA-LDPE film with 10 % SA (26 % increasing compared to the control), respectively.

Fig. 4.

a: OTR value in the films containing different concentration of SA and EVOH. b: OTR value in LDPE films with different thicknesses and layers number

Giving Fig. 4b, the OTR value was significantly decreased by increasing number of LDPE film layers (P < 0.05), so that increasing number of the film layers from 1 to 4 layers lead to 93.8 % decreasing the OTR value. This result was consistent with the increasing thickness of LDPE film (Fig. 4b). As well as, number of LDPE film layers remarkably affect on the OTR value compared to thickness of LDPE film (Fig. 4b).

Janjarasskul et al. (2011) reported that OTR value of whey protein film was decreased by adding ascorbic acid. They attributed the reason of this fact to change of microstructure resulting adding ascorbic acid. However, results of the present study not compatible with result of Ramos et al. (2012), which reported that OTR value of polypropylene film was decreased by adding carvacrol and thymol.

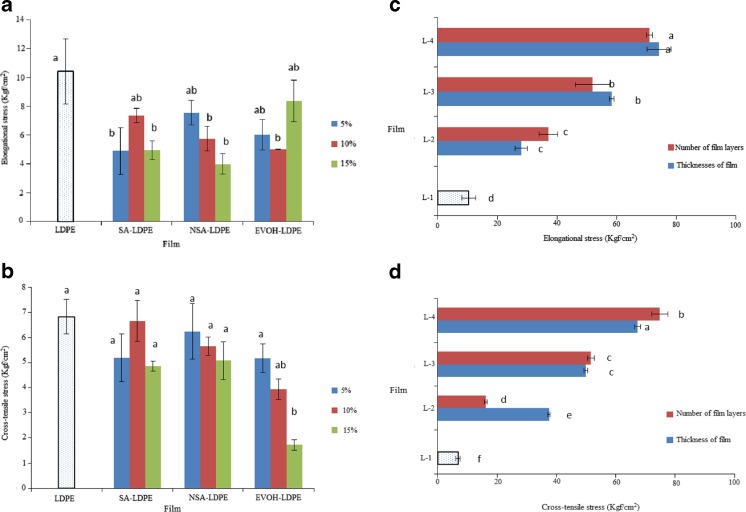

Mechanical properties

Elongational stress of LDPE film was significantly decreased by adding SA in the both form (nano and micro) at the all concentrations (except at 10 % for SA-LDPE and 5 % for NSA-LDPE) (P > 0.05) (Fig. 5a). However, no significant difference between elongational stress of active films containing SA and the control (pure LDPE) was observed (P > 0.05) (Fig. 5b). Although elongational stress and cross-tensile stress of SA-LDPE and NSA-LDPE films changed by adding SA, but this changing did not follow any trend and was statistically insignificant (P > 0.05). Our finding is in agreement with observations of Janjarasskul et al. (2011).

Fig. 5.

a: Elongational stress of LDPE films containing different concentrations of SA and EVOH. b: Cross-tensile stress of LDPE films containing different concentrations of SA and EVOH. cElongational stress of LDPE films with different thicknesses and layers number. d: Cross-tensile stress of LDPE films with different thicknesses and layers number

Although elongational and cross-tensile stresses of EVOH-LDPE film was less than pure LDPE, but this decreasing was significant alone at 10 and 15 % for elongational and cross-tensile stresses (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5b and b).

Giving Fig. 5c and d, the elongational and cross-tensile stresses were significantly increased by increasing thickness and number of LDPE film layers. This result is in agreement with observations of Shin et al. (2011), which prepare and characterize multilayer film incorporating oxygen scavenger.

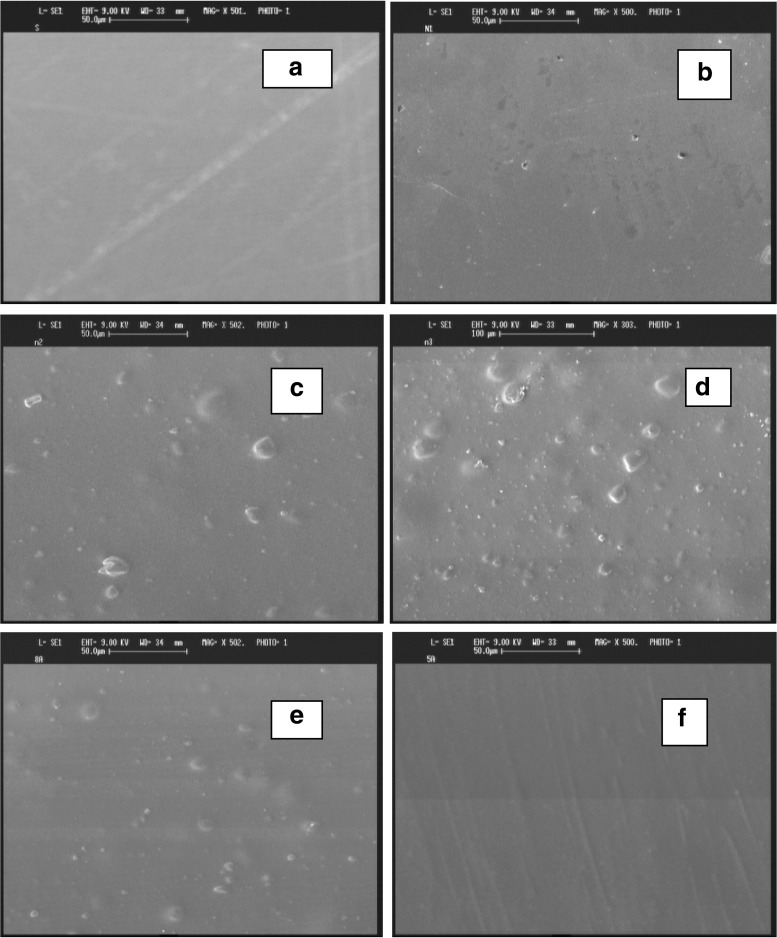

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images

As it is obvious, pure LDPE film has uniform and homogeneous; as well as, SA particles often were distributed as spherical and bright spots in LDPE matrix (Fig. 6). The uniformity of surface morphology was decreased by increasing SA concentration, however pores of the film was increased at this condition. This result is similar to observations of other researcher about adding an additive matrix of polymer (Galdi and Incarnoto 2011; Cui et al. 2011; Ramos et al. 2012). Giving the result of SEM, SA-LDPE film containing 10 % SA had more uniformity of surface compared to NSA-LDPE film containing 10 % SA. In addition, EVOH-LDPE film has uniform surface morphology and it revealed that adding EVOH to matrix of polymer lead to form a pulled layered texture and oriented (Fig. 6f).

Fig. 6.

SEM images of pure LDPE (a), NSA-LDPE film containing 5 % SA (b), NSA-LDPE film containing 10 % SA (c), NSA-LDPE film containing 15 % SA (d), SA-LDPE film containing 10 % SA (e), and EVOH-LDPE film containing 10 % EVOH (f)

Colorimetry

Giving Table 2, L* value was increased by adding SA to LDPE film in the both forms (micro and nano), although this increasing was significant at some the concentrations of SA. In addition, this value for EVOH-LDPE was insignificantly more than pure LDPE. This finding is similar to observation Shin et al. (2011) about PE films containing oxygen scavenger, whereas this is against with observation of Byun et al. (2010) about PLA film containing BHT and tocopherol. SA-LDPE film has significantly more a* value than pure LDPE film, whereas, this value for NSA-LDPE and EVOH-LDPE films was almost similar to pure LDPE film. b* value of SA-LDPE, NSA-LDPE, and EVOH-LDPE films were measure less compared to pure LDPE film. EVOH-LDPE films at different concentrations of SA have the highest ΔE compared to pure LDPE film; however, ΔE of SA-LDPE and NSA-LDPE was almost similar to ΔE of pure LDPE film. The minimum L*, a*, b*, and ΔE values were measured for EVOH-LDPE containing 5 % EVOH, pure LDPE, SA-LDPE containing 5 % SA, and NSA-LDPE containing 15 % SA, respectively.

Table 2.

Color parameters (L*, a*, b*, and ∆E) of LDPE, SA-LDPE, NSA-LDPE, and EVOH-LDPE films

| Film | Concentration (%) | L* | a* | b* | ∆E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDPE | – | 16.53 ± 4.10c | 0.03 ± 0.01a | −2.17 ± 0.50b | |

| 5 | 25.61 ± 2.20ab | −0.09 ± 0.05b | −1.61 ± 0.10ab | 41.12 ± 2.20bc | |

| SA-LDPE | 10 | 24.03 ± 2.60abc | −0.05 ± 0.19ab | −1.51 ± 0.10ab | 42.70 ± 2.50bc |

| 15 | 23.30 ± 0.70abc | −0.10 ± 0.30b | −1.92 ± 0.20ab | 43.35 ± 0.70abc | |

| 5 | 24.62 ± 3.20abc | −0.01 ± 0.03ab | −1.80 ± 0.40ab | 42.07 ± 3.10bc | |

| NSA-LDPE | 10 | 24.01 ± 1.80abc | −0.01 ± 0.03ab | −2.14 ± 0.00b | 42.60 ± 1.80bc |

| 15 | 29.45 ± 1.50a | −0.03 ± 0.02ab | −1.78 ± 0.30ab | 37.31 ± 1.40c | |

| 5 | 16.14 ± 1.90c | −0.04 ± 0.02ab | −1.57 ± 0.20ab | 50.48 ± 1.90a | |

| EVOH-LDPE | 10 | 20.69 ± 3.90bc | −0.03 ± 0.01ab | −1.14 ± 0.30a | 46/06 ± 3.80ab |

| 15 | 20.97 ± 2.80abc | −0.02 ± 0.00ab | −.1.16 ± 0.40ab | 45.77 ± 2.70ab |

Different letters within the columns indicate significant difference (P < 0.05). L*: (lightness); a*: (Red-green); and b*: (yellow-blue)

L* value of LDPE film was significantly increased by increasing thickness from 7.5 to 45 μm (P < 0.05). This increasing was observed by increasing number of film layer but it was significant only for four-layer films (P < 0.05). No significant difference was observed between a* value of LDPE films with different thickness and number of film layer (except thickness of 45 μm). b* and ΔE values of LDPE films was significantly decreased by increasing thickness and number of film layer (P < 0.05) (Table 3). Galdi and Incarnoto (2011) reported that packaged banana with active PET films containing 10 % amosorb (AMS) have the best color.

Table 3.

Color parameters of LDPE films with different thickness and number of layers

| L* | a* | b* | ∆E | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thickness (μm) | 7.5 | 16.53 ± 4.1c | 0.03 ± 0.01a | −2.17 ± 0.50a | – |

| 15 | 18.18 ± 0.5bc | −0.01 ± 0.00a | −3.35 ± 0.30ab | 48.24 ± 0.50bc | |

| 30 | 25.16 ± 2.8ab | −0.10 ± 0.04ab | −3.46 ± 0.70ab | 41.30 ± 2.70cd | |

| 45 | 25.79 ± 0.80a | −0.19 ± 0.03b | −5.81 ± 0.40c | 40.43 ± 0.80cd | |

| Number of layers | 1 | 16.53 ± 4.10c | 0.03 ± 0.01a | −2.17 ± 0.50a | – |

| 2 | 20.34 ± 1.10abc | 0.02 ± 0.00a | −3.51 ± 0.20b | 46.07 ± 1.00ab | |

| 3 | 22.69 ± 0.80abc | −0.03 ± 0.00a | −4.22 ± 0.10b | 43.65 ± 0.80bc | |

| 4 | 26.73 ± 1.00a | −0.05 ± 0.00a | −4.53 ± 0.50bc | 39.61 ± 0.90d | |

Different letters within the columns indicate significant difference (P < 0.05)

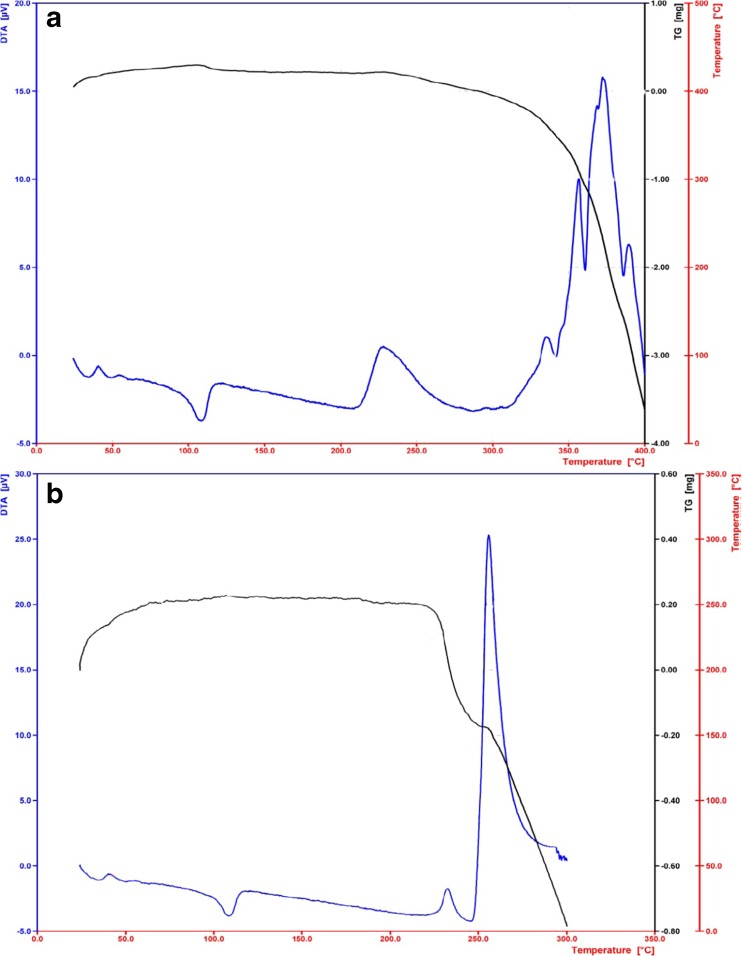

Thermal analysis

As it is shown in Fig. 7, adding SA to matrix of LDPE led to faster degradation of this polymer. The result revealed that there were two degradation steps before the main step polymer degradation in active films containing SA.

Fig. 7.

FTIR spectrums of pure LDPE (a), NSA-LDPE film containing 10 % SA in aquatic model at the first day (b), NSA-LDPE film containing 10 % SA in aquatic model at 13th day (c), NSA-LDPE film containing 10 % SA in ethanolic model at the first day (d), SA-LDPE film containing 10 % SA in aquatic model at the first day (e)

Giving thermograms of thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), the first degradation step in the LDPE films containing SA started at 232–235 °C (Table 4). However, the first degradation step in pure LDPE film started at 228 °C that is closed to the first degradation temperature in the active films; hence, this degradation is related to additives of polymer. The second degradation step in the active films containing SA started at 232–235 °C that was much broader. Since the second degradation step not found in pure LDPE film, it can be concluded that the degradation occurred in this range is related to the decomposition of SA. Also in another study, degradation temperature of SA was measured 249.2 °C (Lopez-de-Dicastillo et al. 2012). The first and second degradation temperature of SA-LDPE and NSA-LDPE films containing 10 % SA were close to each other; however, their weight loss was different at the above temperatures that this can be due to lack of uniform distribution of SA in the polymer matrix (Table 4). Ramos et al. (2012) observed two steps degradation for active polypropylene films containing carvacrol, which were related to decomposition of carvacrol (at 115 °C) and thermal degradation of polymer matrix, respectively.

Table 4.

TGA parameters of SA-LDPE and NSA-LDPE films containing different SA

| Active film | The first degradation step | The second degradation step | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (°C) | Weight loss | Temperature (°C) | Weight loss | |

| NSA-LDPE containing 5 % SA | 234 | 2.6 | 251 | 3.2 |

| NSA-LDPE containing 10 % SA | 233 | 1.2 | 257 | 1.4 |

| NSA-LDPE containing 15 % SA | 232 | 1.8 | 253 | 3.8 |

| SA-LDPE containing 10 % SA | 235 | 0.7 | 252 | 1.4 |

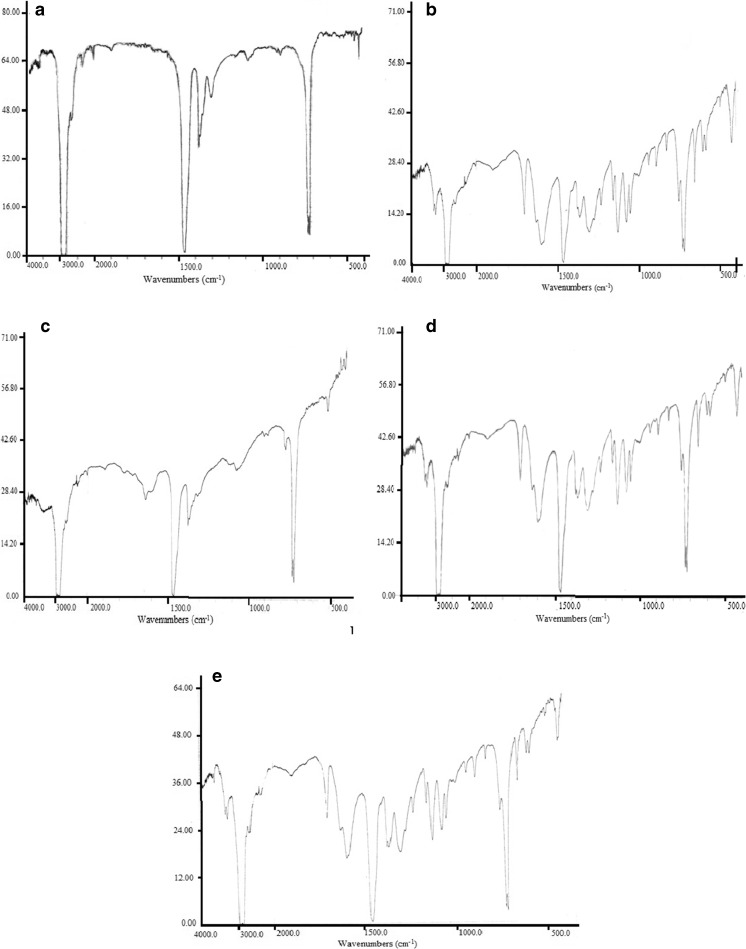

FTIIR

Giving Fig. 8, six absorption peak area were observed for pure LDPE at wavenumbers 730/720 (binary), 1380, 1462, 2829 and 2960 cm−1, which were related to C-H group with oscillating vibratory movement, C-H group with bending vibration movement, C-H group with symmetric stretching vibration movement, and C-H group asymmetric stretching vibration, respectively. These results are in agreement with observations of Cui et al. (2011). According to Fig. 8, two absorption peak were observed in 1580–1635 range and 1705 cm−1 for NSA-LDPE film on the first day in the FTIR spectrum that are related to C=O functional group inside ring and ketonic group (C=O) in the structure of SA, respectively, which confirms the presence of SA in the polymer. A distinct difference was observed by comparing FTIR spectrum of NSA-LDPE containing 10 % SA in ethanolic and aquatic models, so that migration of SA from NSA-LDPE film was less in ethanolic model than aquatic (Fig. 8c and d). Generally, the results FTIR revealed that migration of SA to aquatic environment was more than ethanolic model. As well as, smaller particle sizes of SA increase the releasing and the migration.

Fig. 8.

TGA curves of pure LDPE (a), NSA-LDPE film containing 10 % SA (b)

Tests of relate to the packaged peanut

PV

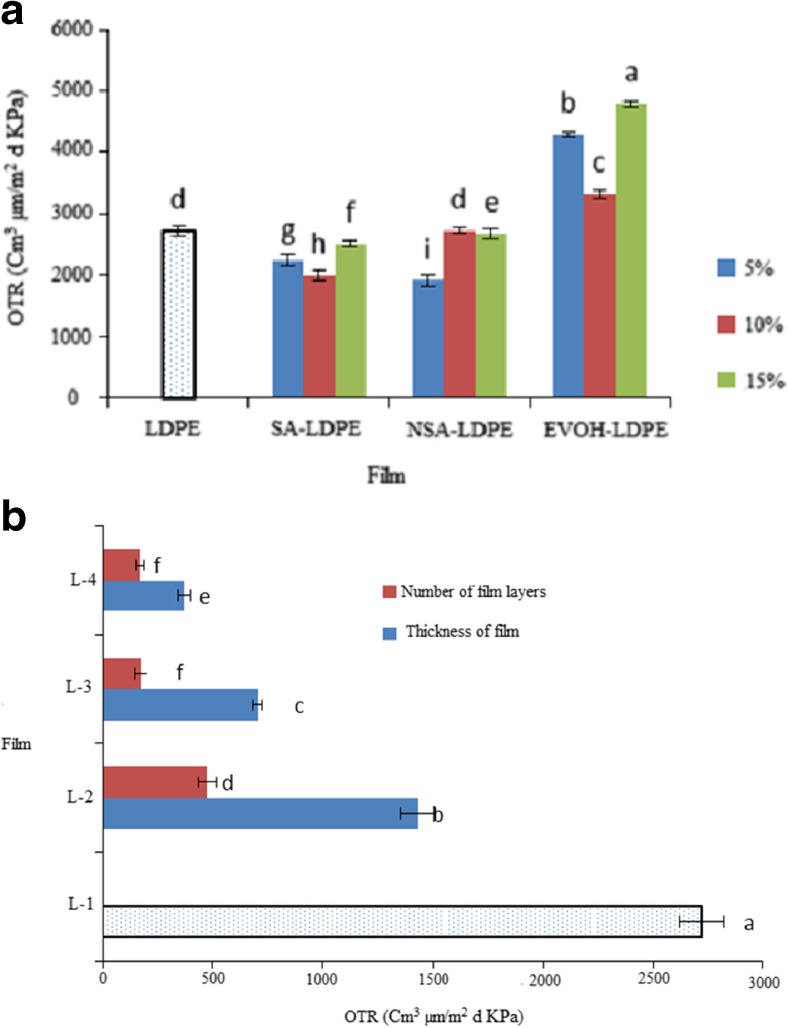

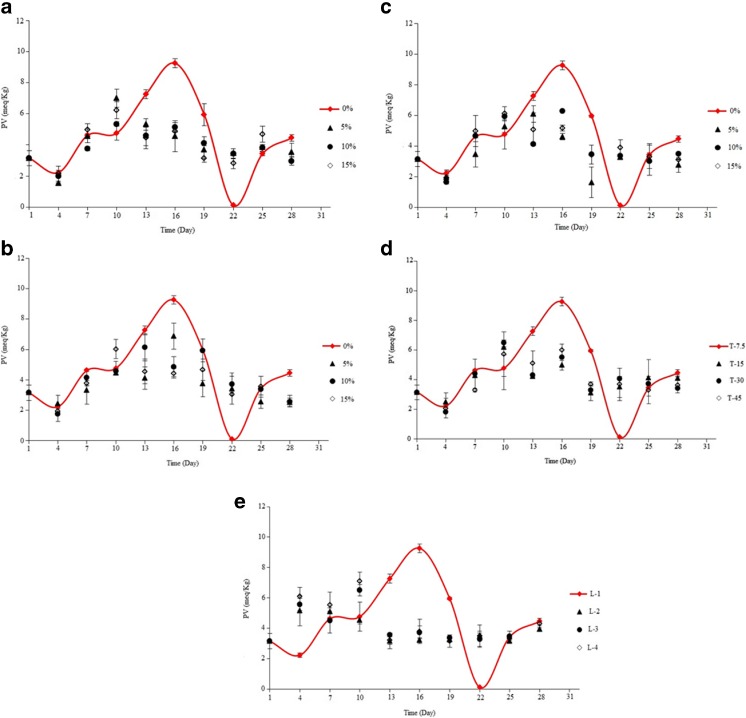

At the first, PV of peanut packaged in pure LDPE films almost was increased, so that it reached to the maximum value after 16th day of storage period and it followed by decreasing until the 22th day (Fig. 9a). The decreasing trend is due to instability of hydroperoxides and its decompose to secondary oxidation compounds (Farhoosh 2007). After the 22th day, concentration of hydroperoxides in peanuts packed in pure LDPE film was increased again. PV of peanut packed in active film containing SA-LDPE reached to the maximum value faster compared to the control sample. However, increasing rate of PV in this sample was less compared to the control, so that the maximum PV of the control at 16th day was measured 9.3 meq/Kg, whereas the maximum PV of peanut packaged in SA-LDPE films at 10th day was observed 7, 5.3 and 6.2 meq/Kg at concentrations of 5, 10 and 15 %, respectively. Giving the result, SA-LDPE films containing 10 % SA have the maximum inhibition from the oxidation because of had the lowest maximum of PV compared to the other samples, which was in an agreement with result of OTR (Fig. 9a).

Fig. 9.

a: PV of peanut packaged by SA-LDPE films containing different concentrations of SA during the storage time. b: PV of peanut packaged by NSA-LDPE films containing different concentrations of SA during the storage time. c: PV of peanut packaged by EVOH-LDPE films containing different concentrations of EVOH during the storage time. d: PV of peanut packaged by LDPE films with different thicknesses during the storage time. e: PV of peanut packaged by LDPE films with different layers number during the storage time

PV of peanut packaged in NSA-LDPE and EVOH-LDPE films were significantly decreased compared to the control (P < 0.05) (Fig. 9b and c). Against the sample packaged in SA-LDPE films, in these samples, time of reaching to maximum PV at different concentrations of SA was not the same (Fig. 9b). Giving Fig. 9b, peanuts packaged in NSA-LDPE film containing 5 % SA has less PV than the samples packaged in this film containing the other concentration of SA, which this is probably due to its low permeability against oxygen.

As it is obvious in Fig. 9d, PV of packaged peanut was significantly reduced by increasing thickness of LDPE film (P < 0.05); however, no significant difference between PV of the samples packaged with thicknesses of 15, 30 and 45 μm was observed (P < 0.05). As well as, the maximum PV in the samples packaged with thicker LDPE than 7.5 μm was measured on 10th day of the storage period.

PV of packaged peanut was decreased by increasing number of LDPE film; as well as an interesting result, the samples packaged with two or more layers have a upward trend for the PV From the beginning, however, in the sample packaged with monolayer LDPE film opposite of true (Fig. 9e). Cui et al. (2011) observed that PV of food models was reduced by increasing SA: modified iron ratio up to 7:3 in matrix of LDPE, which reported this is due to less oxygen penetration rate of these films.

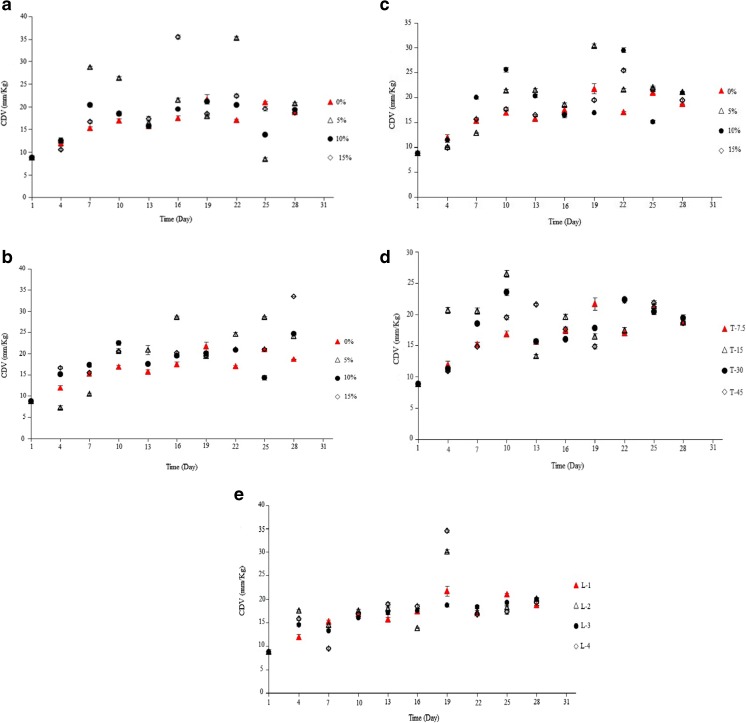

CDV

Measurement of CDV compounds caused by polyunsaturated lipids is a sensitive method that evaluates early stages of lipid oxidation. CDV of the samples packaged with active films and the control were gradually increased so that no significant difference between them (except for the samples containing 5 %) was observed (Fig. 10a and b). CDV of peanut packaged with SA-LDPE film containing 5 % SA was measured significantly more than the other samples at 7th, 10th and 22th day of the storage period (P < 0.05), which this result is in agreement with the observation of PV at the similar days (Fig. 10a). The above result revealed that although SA is effective in preventing formation of hydroperoxides but it is not so efficient in preventing degradation of fatty acids and formation of conjugated diene compounds. As it is shown in Fig. 10c, CDV of the samples packaged with EVOH-LDPE film, in many cases, was significantly more than the control sample (P < 0.05). The maximum of CDV for peanut packaged with EVOH-LDPE film containing 5 % SA was measured on 19th day of storage period (Fig. 10c). Giving Fig. 10d and e, the CDV of LDPE films was gradually increased in the films with different thicknesses and number of the film layers during the storage period.

Fig. 10.

a: CDV of peanut packaged by SA-LDPE films containing different concentrations of SA during the storage time. b: CDV of peanut packaged by NSA-LDPE films containing different concentrations of SA during the storage time. c: CDV of peanut packaged by EVOH-LDPE films containing different concentrations of EVOH during the storage time. d: CDV of peanut packaged by LDPE films with different thicknesses during the storage time. e: CDV of peanut packaged by LDPE films with different layers number during the storage time

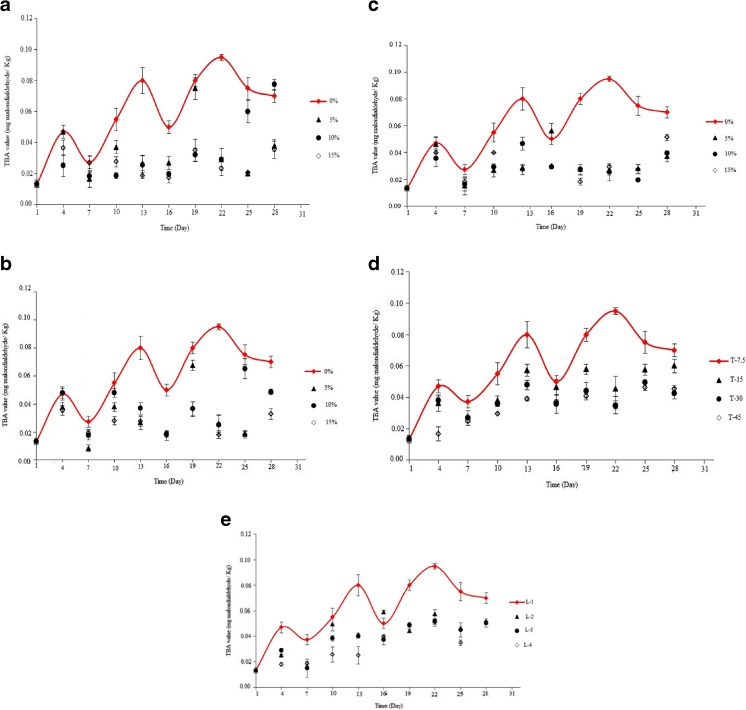

TBA value

TBA value is widely used to determine secondary oxidation products such as aldehydes or carbonyl that caused to off-odor of oils. Giving Fig. 11, TBA value of the samples packaged in SA-LDPE, NSA-LDPE, and EVOH-LDPE films were significantly less than the control (P < 0.05). The maximum TBA value of the samples packaged in SA-LDPE films containing 5, 10 and 15 % SA were observed on 19th, 28th and 4th day of storage period, respectively. The maximum preventing from progress of the second stage oxidation and formation of secondary compounds was measured for the samples packaged in SA-LDPE film containing 15 % SA (Fig. 11a). Giving Fig. 11b, the minimum TBA value range was measured for the sample packaged in NSA-LDPE film containing 15 % SA. The highest TBA value of the samples packaged in EVOH-LDPE films containing 5, 10 and 15 % SA were observed on 16th, 13th and 10th day of storage period, respectively (Fig. 11c). TBA value of peanut packaged in LDPE was significantly decreased with increasing thickness and number of the film layers (P < 0.05) (Fig. 11d and e). The samples packaged in LDPE films with thickness of 45 μm have the lowest range of TBA value and the highest difference with the control. Giving Fig. 11e, no significant difference was observed between TBA value of peanuts packaged in LDPE multilayer film (P > 0.05). The maximum of TBA value was observed on 16th, 19th and 19th for the samples packaged in two-layers, three-layers, four-layers LDPE films, respectively.

Fig. 11.

a: TBA value of peanut packaged by SA-LDPE films containing different concentrations of SA during the storage time. b: TBA value of peanut packaged by NSA-LDPE films containing different concentrations of SA during the storage time. c: TBA value of peanut packaged by EVOH-LDPE films containing different concentrations of EVOH during the storage time. d: TBA value of peanut packaged by LDPE films with different thicknesses during the storage time. e: TBA value of peanut packaged by LDPE films with different layers number during the storage time

Barbosa-Pereira et al. (2013) used active film containing tocopherols to extend the shelf life of fish, which reported that TBA value was decreased by this film at 4 °C and during 21-day storage period. Lopez-de-Dicastillo et al. (2012) used EVOH-LDPE active films containing 5 % SA to packaging sardine and their results revealed that oxidation rate of the sardine packaged in the active films is less than the control sample. Among active films studied by these researchers, the films containing tea extract and ascorbic acid have the highest and lowest inhibitory effect on the oxidation, respectively. As well as, these researchers reported that ascorbic acid could even act as prooxidant in the secondary oxidation and thereby TBA value is increased (Lopez-de-Dicastillo et al. 2012).

Microbial evaluation

Giving Table 5, total count of microorganisms and molds and yeasts in any of the tested samples were not more than the authorized standard. Based on Iranian national standard authorized maximum for total count of microorganisms and mold and yeast count in peanut are 104 and 100 CFU/g, respectively. As an interesting result, total count of microorganisms of peanuts packaged in LDPE with thickness of 15 μm, SA-LDPE and NSA-LDPE films containing 5 % SA remained zero during the storage period. As well as, contamination of mold and yeast was not observed for the samples packaged in EVOH-LDPE film with 15 % EVOH. According to the results, EVOH-LDPE film with 15 % EVOH shows the highest inhibitory effect against mold and yeast contamination (Table 6).

Table 5.

Total count (CFU/g) of pure LDPE, SA-LDPE, NSA-LDPE, EVOH-LDPE, and LDPE with different thickness and number of layers during storage time

| Film | Concentration (%)/Thickness (μm) /Number of layer | First week | Second week | Third week | Fourth week |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDPE | – | 0 | 30 | 0 | 230 |

| SA-LDPE | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 15 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 200 | |

| NSA-LDPE | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 65 | |

| 15 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 | |

| EVOH-LDPE | 5 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 |

| 10 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | |

| 15 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 0 | |

| LDPE | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 30 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 50 | |

| 45 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 20 | |

| LDPE | 2 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 10 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 10 | |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 |

Table 6.

Mold and yeast count (CFU/g) of pure LDPE, SA-LDPE, NSA-LDPE, EVOH-LDPE, and LDPE with different thickness and number of layers during storage time

| Film | Concentration (%)/Thickness (μm) /Number of layer | First week | Second week | Third week | Fourth week |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDPE | – | 0 | 10 | 10 | 20 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 10 | |

| SA-LDPE | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 |

| 15 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 95 | |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | |

| NSA-LDPE | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 20 |

| 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | |

| EVOH-LDPE | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 15 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 10 | |

| LDPE | 30 | 10 | 0 | 20 | 20 |

| 45 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 15 | |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 60 | |

| LDPE | 3 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 20 |

| 4 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

Dukalska et al. (2011) assessed effect of active packaging on shelf life of soft cheese KLEO. They reported that this packaging increased the shelf life of this cheese from 15 to 32 days. Ramos et al. (2012) evaluated antimicrobial activity of polypropylene films containing different concentrations of thymol and carvacrol against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Their results revealed that thymol has more antimicrobial activity than carvacrol.

Conclusions

The results of this study demonstrated that the active films containing SA (especially at 10 % SA) as oxygen scavenger present suitable performance and features to increase the shelf life of peanuts. As well as, general review of results revealed that the multilayer films (especially four-layers) have suitable performance for increasing the shelf life of peanuts. However, flexibility of these films and its applications in food packaging were decreased.

References

- Andersen HJ, Rasmussen MA. Interactive packaging as protection against photodegradtion of the color of pasteurized, sliced ham. Int J Food Sci Technol. 1992;27:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1992.tb01172.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Antunez PD, Botero Omary M, Rosentrater KA, Pascall M, Winstone L. Effect of an oxygen scavenger on the stability of preservative-free flour tortillas. J Food Sci. 2012;71(1):1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2011.02470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ASTM . Standard test methods for water vapor transmission of material. E96-95. Annual book of ASTM. Philadelphia: American Society for Testing and Materials; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa-Pereira L, Cruz JM, Sendon R, Rodriguez Bernaldo de Quiros A. Development of antioxidant active films containing tocopherols to extend the shelf life of fish. Food Control. 2013;31:236–243. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2012.09.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brody AL, Bugusu B, Han JH, Koelsch Sand C, Mchugh TH. Innovative food packaging solutions. J Food Sci. 2008;73(8):107–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2008.00933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byun Y, Kim YT, Whiteside S. Characterization of an antioxidant polylactic acid (PLA) film prepared with α-tocopherol, BHT and polyethylene glycol using cast extruder. J Food Eng. 2010;100:239–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2010.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calatayud M, Lopez-de-Dicastilla C, Lopez-Carbollo G, Velez D, Munoz PH, Gavora R. Active films based on cocoa extract with antioxidant, antimicrobial and Biological applications. Food Chem. 2013;139:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.01.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colín-Chávez C, Soto-Valdez H, Peralta E, Lizardi-Mendoza J, Balandrán-Quintana R (2013) Diffusion of natural astaxanthin from polyethylene active packaging films into a fatty food simulant. Food Res Int 54:873--880

- Cui L, Xu LP, Tsai FC, Zhu P, Jiang T, Yeh JT. Oxygen depletion of glucose-grafted polyethylene resins filled with sodium ascorbate/modified iron compounds. J Polym Res. 2011;18:1301–1313. doi: 10.1007/s10965-010-9533-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dukalska L, Muizniece-Brasava S, Murniece I, Dabina-Bicka I, Kozlinskis E, Sarvi S. Influence of active packaging on shelf life of soft cheese KLEO. World Acad Sci Eng Technol. 2011;5:254–260. [Google Scholar]

- Farhoosh R (2007) The effect of operational parameters of the Rancimat method on the determination of the oxidative stability measures and shelf-life prediction of soybean oil. J Am Oil Chem Soc 84:205--209

- Galdi MR, Incarnoto L. Influence of composition on structure and barrier properties of active PET films for food packaging applications. Packag Technol Sci. 2011;24:89–102. doi: 10.1002/pts.917. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han JH, Hwang HM, Min S, Krochta JM. Coating of peanuts with edible whey protein film containing α-tocopherol and ascorbyl palmitate. J Food Sci. 2008;73(8):349–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2008.00910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISO 7218 (2007) Microbiology of food and animal feeding stuffs – General requirements and guidance for microbiological examinations

- Janjarasskul T, Tananuwong K, Krochta JM. Whey protein film with oxygen scavenging function by incorporation of ascorbic acid. J Food Sci. 2011;76(9):561–568. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2011.02409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-de-Dicastillo C, Nerin C, Alfaro P, Catala R, Gavara R, Hernandez-Munoz P. Development of new antioxidant active packaging films based on ethylene vinyl alcohol copolymer (EVOH) and green tea extract. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59(14):7832–7840. doi: 10.1021/jf201246g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-de-Dicastillo C, Gomez-Estaca J, Catola R, Gavora R, Hernandez-Munoz P. Active antioxidant packagingfilms: development and effect on lipid stability of brined sardines. Food Chem. 2012;131:1376–1384. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-de-Dicastillo C, Castro-Lopez MM, Ares A, Castro-Lopez M, Abad MJ, Maroto J, Paseiro-Losado P. Immubilization of green tea extract on polypropylene films to control the antioxidant activity in food packaging. Food Res Int. 2013;53:522–528. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2013.05.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mexis SF, Kontominas MG. Effect of oxygen absorber, nitrogen flushing, packaging material oxygen transmission rate and storage conditions on quality retention of raw whole unpeeled almond kernels (Prunus dulcis) Food Sci Technol. 2010;43:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Mu H, Gao H, Chen H, Tao F, Fang X, Ge L. A nanosised oxygen scavenger: preparation and antioxidant application to roasted sunflower seeds and walnuts. Food Chem. 2013;136:245–250. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.07.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’keefe, Wiley VA, Knauft DA. Comparison of oxidative stability of high- and normal-oleic peanut oils. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1993;70(5):489–492. doi: 10.1007/BF02542581. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira de Abreu DA, Villalba Rodriguez K, Cruz JM. Extraction, purification and characterization of an antioxidant extract from barley husks and development of an antioxidant active film for food package. Innovative Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2012;13:134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2011.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prnbylski LA, Finerty MW, Grodner RM, Gerdes DL. Extension of shelf-life of iced fresh channel catfish fillets using modified atmospheric packaging and low dose irradiation. J Food Sci. 1989;45(2):269–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1989.tb03058.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos M, Jimenez A, Peltzer M, Garrigos MC. Characterization and antimicrobial activity studies of polypropylene films with carvacrol and thymol for active packaging. J Food Eng. 2012;109:513–519. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2011.10.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saguy IS, Shani A, Weinberg P, Garti N. Utilization of jojoba oil for deep-fat frying of foods. Lebensm Wiss Technol. 1996;29:573–577. doi: 10.1006/fstl.1996.0088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shantha NC, Decker EA. Rapid, sensitive, iron-based spectrophotometric methods for determination of peroxide values of food lipids. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1994;77:21–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin Y, Shin J, Lee YS. Preparation and characterization of multilayer film incorporationg oxygen scavenger. Macromol Res. 2011;19(9):869–875. doi: 10.1007/s13233-011-0912-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iranian National Standard (2008a) Microbiology of food and animal feed, a comprehensive method for the enumeration of mold and yeast. Standard NO. 10899.1

- Iranian National Standard (2008b) The molecular structure of polymers infrared spectrometry. Standard NO. 8503

- Suppakul P, Miltz J, Sonneveld K, Bigger SW. Active packaging technologies with an emphasis on antimicrobial packaging and its applications. J Food Sci. 2003;68(2):408–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2003.tb05687.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yolmeh M, Najafzadeh M. Optimisation and modelling green bean’s ultrasound blanching. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2014;49(12):2678–2684. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.12605. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yolmeh M, Habibi-Najafi MB, Farhoosh R. Optimisation of ultrasound-assisted extraction of natural pigment from annatto seeds by response surface methodology (RSM) Food Chem. 2014;155:319–324. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahedi Y, Mazaheri-Tehrani M. Development of spreadable Halva fortified with soy flour and optimization of formulation using mixture design. J Food Qual. 2012;35:390–400. doi: 10.1111/jfq.12003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]