Abstract

Renal function generally is assessed by measurement of GFR and urinary albumin excretion. Other intrinsic kidney functions, such as proximal tubular secretion, typically are not quantified. Tubular secretion of solutes is more efficient than glomerular filtration and a major mechanism for renal drug elimination, suggesting important clinical consequences of secretion dysfunction. Measuring tubular secretion as an independent marker of kidney function may provide insight into kidney disease etiology and improve prediction of adverse outcomes. We estimated secretion function by measuring secreted solute (hippurate, cinnamoylglycine, p-cresol sulfate, and indoxyl sulfate) clearance using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometric assays of serum and timed urine samples in a prospective cohort study of 298 patients with kidney disease. We estimated GFR by mean clearance of creatinine and urea from the same samples and evaluated associations of renal secretion with participant characteristics, mortality, and CKD progression to dialysis. Tubular secretion rate modestly correlated with eGFR and associated with some participant characteristics, notably fractional excretion of electrolytes. Low clearance of hippurate or p-cresol sulfate associated with greater risk of death independent of eGFR (hazard ratio, 2.3; 95% confidence interval, 1.1 to 4.7; hazard ratio, 2.5; 95% confidence interval, 1.0 to 6.1, respectively). Hazards models also suggested an association between low cinnamoylglycine clearance and risk of dialysis, but statistical analyses did not exclude the null hypothesis. Therefore, estimates of proximal tubular secretion function correlate with glomerular filtration, but substantial variability in net secretion remains. The observed associations of net secretion with mortality and progression of CKD require confirmation.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, epidemiology and outcomes, proximal tubule

Glomerular filtration and urinary protein excretion are the accepted measures of kidney function used to evaluate presence and severity of CKD.1–4 GFR helps inform optimal medication dosing and predicts risk of cardiovascular events, progression to ESRD, and death.5–11 Urinary albumin excretion complements GFR for predicting cardiovascular disease and ESRD.5,6

In additional to filtration and reclamation of filtered albumin, kidney functions include secretion of organic solutes, synthesis of homeostatic hormones, and maintenance of electrolyte and acid-base status. Proximal tubule secretion represents an essential kidney function for rapidly clearing endogenous substances and administered medications from the circulation, including protein-bound molecules. Moreover, tubular secretion represents the primary renal mechanism responsible for the elimination of most administered drugs and their metabolites.4,12–15 Despite the biologic importance of proximal tubule secretion, this function is infrequently measured because of uncertainty regarding specific endogenous compounds that are cleared by secretion, lack of validated laboratory assays for secreted metabolites, and the cumbersome nature of timed urine collections.

We developed liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometric (MS) assays to quantify blood and urine concentrations of four solutes that are primarily cleared by proximal tubule secretion: hippurate (HA), cinnamoylglycine (CMG), p-cresol sulfate (PCS), and indoxyl sulfate (IS).4,13,15–18 HA is a classic substrate of organic anion transporters 1 and 3 on the basolateral membrane of the proximal tubule.15 CMG is a putative gut–derived metabolite that was shown to have substantially greater urinary clearance than creatinine in a recent discovery analysis.4 PCS and IS are also gut bacteria–produced metabolites that have been investigated as candidate uremic toxins.19

We used timed urine and spot serum samples to estimate renal tubular secretion on the basis of the clearance of these four solutes in 298 patients with CKD from a prospective cohort study. In parallel, we estimated glomerular filtration as the average clearance of creatinine and urea from the same timed urine and serum samples. Herein, we evaluate proximal tubule solute clearances relative to filtration and urinary albumin excretion, describe associations with patient characteristics, and estimate associations with mortality and progression to dialysis.

Results

Study participants were generally middle aged (mean of 59.6 years of) and predominantly men (79%); 53% had diabetes (Table 1). The median eGFR was 41.8 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (interquartile range [IQR], 28.5–59.9 ml/min per 1.73 m2), and the median urinary albumin excretion was 180.9 mg/d (IQR, 20.9–918.0 mg/d). The distributions of secreted solute clearances were quite different than those of filtration, with HA and CMG more variable and PCS and IS less variable (IQR, 60–208 ml/min for HA, 180–621 ml/min for CMG, 5–13 ml/min for PCS, and 12–35 ml/min for IS).

Table 1.

Selected participant characteristics

| Participant Characteristic | n=298a |

|---|---|

| Age (yr), mean (SD) | 59.6 (13.8) |

| Men, n (%) | 236 (79.2) |

| Black race, n (%) | 78 (26.2) |

| Other nonwhite race, n (%) | 27 (9.1) |

| Diabetes, n (%)b | 158 (53.0) |

| Conventional measures of kidney function | |

| Average urea and creatinine clearance (ml/min), median (IQR) | 47.5 (29.4–72.4) |

| Creatinine clearance (ml/min), median (IQR) | 69.1 (44.7–107.0) |

| eGFR (CKD-EPI 2009; ml/min per 1.73 m2), median (IQR)c | 41.1 (28.1–63.1) |

| Albumin excretion rate (mg/d), median (IQR) | 180.9 (20.9–918.0) |

| HA clearance (ml/min), median (IQR) | 328.5 (179.8–620.8) |

| HA (serum; μg/ml), median (IQR) | 1.04 (0.51–1.95) |

| HA (urine; μg/ml), median (IQR) | 227.0 (129.5–386.2) |

| CMG clearance (ml/min), median (IQR) | 112.9 (60.1–207.7) |

| CMG (serum; μg/ml), median (IQR) | 0.014 (0.004–0.038) |

| CMG (urine; μg/ml), median (IQR) | 1.12 (0.27–2.69) |

| PCS clearance (ml/min), median (IQR) | 8.3 (5.3–12.8) |

| PCS (serum; μg/ml), median (IQR) | 12.1 (6.5–20.9) |

| PCS (urine; μg/ml), median (IQR) | 69.0 (32.5–110.6) |

| IS clearance (ml/min), median (IQR) | 20.2 (12.3–34.8) |

| IS (serum; μg/ml), median (IQR) | 3.2 (1.9–4.9) |

| IS (urine; μg/ml), median (IQR) | 43.3 (23.7–69.7) |

PCS and IS assays completed on 291 participants because of sample limitations.

Diabetes on the basis of self-report or use of diabetes medications.

CKD-EPI 2009 estimating equation for eGFR on the basis of serum creatinine, age, race, and sex.

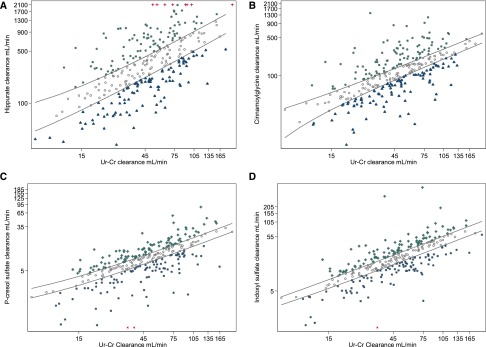

Substantial interindividual variation in clearance of HA and CMG was observed across the measured range of estimated glomerular filtration on the basis of the average of creatinine and urea clearance (Figure 1). PCS and IS showed markedly lower overall range but similar proportional variability with respect to the distribution of the average of creatinine and urea clearance, although there were clear outliers on the lower range of function. On the logarithmic scale, the cohort was stratified into three equal–sized groups for each solute on the basis of estimated net proximal tubule solute clearances relative to glomerular filtration (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Visualization of correlations between the ranges of secreted solute clearance and filtration function in a kidney patient population. Scatter plots of (A) HA, (B) CMG, (C) PCS, and (D) IS clearances over the average of urea and creatinine (Ur-Cr) clearance. Natural logarithmic scale is shown for visual examination of the range, variability, and interindividual differences between four measures of secretion (secreted solute clearance) and filtration (Ur-Cr clearance). Units are given as volume of blood completely cleared of the given solute per unit time (milliliters per minute). Red crosses at the (A) top or (C and D) bottom represent participants with extremely high or low secretion clearances who are displayed at an arbitrary maximal–range value for graphic examination purposes; these participants are included in all statistical analyses using the true data value. Population is separated into three tertile categories using regressions at 33rd and 67th percentiles of secretion over filtration: participants with high (green crosses; category 3), medium (gray circles; category 2), and low (blue triangles; category 1).

The clearances of proximal tubule solutes were modestly correlated with each other (HA-PCS and HA-IS, r=0.3; CMG-HA and CMG-PCS, r=0.4; IS-CMG and IS-PCS, r=0.6) and with the average of creatinine and urea clearance (Table 2). Correlations with creatinine and urea clearance were modestly stronger after log transformation of solute clearances. Correlations of solute clearances with eGFR, as determined by the 2009 Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation (creatinine only), were somewhat lower than those observed for the average of creatinine and urea clearance obtained from the same timed urine and serum samples, with PCS showing strongest correlation with both filtration measures (r=0.5–0.7). Correlations of tubule solute clearances with urine albumin excretion were low (r=<−0.01–0.2).

Table 2.

Correlations among measures of tubular secretion and glomerular filtration

| Filtration Measure | HA Clearance, ml/min | CMG Clearance, ml/min | PCS Clearance, ml/min | IS Clearance, ml/min | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rhoa | P Value | Rhoa | P Value | Rhoa | P Value | Rhoa | P Value | |

| Urea and creatinine clearance, ml/min | 0.42 | <0.001 | 0.35 | <0.001 | 0.66 | <0.001 | 0.40 | <0.001 |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 0.37 | <0.001 | 0.32 | <0.001 | 0.53 | <0.001 | 0.39 | <0.001 |

| Albumin excretion rate, mg/d | 0.03 | 0.66 | 0.16 | <0.01 | <−0.01 | >0.99 | −0.06 | 0.33 |

| HA clearance, ml/min | — | — | 0.38 | <0.001 | 0.28 | <0.001 | 0.26 | <0.001 |

| CMG clearance, ml/min | — | — | — | — | 0.41 | <0.001 | 0.60 | <0.001 |

| PCS clearance, ml/min | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.58 | <0.001 |

| IS clearance, ml/min | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

Pearson (pairwise) correlation coefficient (r); analyses are on an arithmetic scale.

The net clearances of proximal tubule solutes relative to filtration tended to be similar across patient characteristics, with some differences observed by sex and laboratory measurements (Table 3). However, none of these distinctions excluded the possibility of chance after accounting for multiple testing. Men tended to have greater net tubule solute clearance, with 84% in the highest category of HA clearance being men compared with 70% in the lowest category. In continuous analyses, greater net HA clearance was associated with lower systolic BP, current smoking, lower hemoglobin A1C, and lower fractional excretion of uric acid after adjustment for eGFR, age, sex, race, and standardized daily creatinine excretion (data not shown). Greater net CMG clearance was associated with a lower fractional excretion of phosphate and potassium and lower hemoglobin A1C. Greater net PCS clearance was associated with lower fractional excretion of uric acid, calcium, and sodium and higher serum bicarbonate. Greater net IS clearance was associated with the same factors as PCS as well as black race, higher hemoglobin A1C, and lower albumin excretion rate (Supplemental Material).

Table 3.

Net secretion and CKD correlates comparing low (category 1), medium (category 2), and high (category 3) HA clearance for participants with the same average urea and creatinine clearance

| Characteristic, Mean (SD) Unless Noted | Category 1 (Low; n=98) | Category 2 (Medium; n=99) | Category 3 (High; n=99) | P Value for Trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 59.8 (13.8) | 59.4 (14.0) | 59.4 (13.5) | 0.96 |

| Men, n (%) | 69 (70) | 82 (83) | 83 (84) | 0.04 |

| Black race, n (%) | 31 (32) | 24 (24) | 23 (23) | 0.34 |

| Other nonwhite race, n (%) | 8 (8) | 9 (9) | 10 (10) | 0.89 |

| Urea and creatinine clearance, ml/min | 54.2 (31.7) | 54.3 (34.1) | 54.1 (31.6) | >0.99 |

| Daily creatinine excretion/LBM, mg/kga | 29.4 (11.1) | 30.7 (12.4) | 32.2 (12.9) | 0.27 |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2a | 50.0 (27.1) | 46.2 (26.3) | 46.2 (25.1) | 0.50 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 31.9 (8.1) | 32.1 (8.0) | 30.9 (6.3) | 0.50 |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 132.0 (21.7) | 131.3 (21.4) | 129.9 (20.1) | 0.77 |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 15 (15) | 19 (19) | 23 (23) | 0.39 |

| Current alcohol use, n (%) | 30 (31) | 34 (34) | 31 (31) | 0.84 |

| Medications use, n (%) | ||||

| Aspirin | 39 (40) | 32 (32) | 47 (47) | 0.09 |

| Statin | 48 (49) | 57 (58) | 62 (63) | 0.15 |

| H2 blocker | 7 (7) | 8 (8) | 11 (11) | 0.59 |

| Loop diuretic | 38 (39) | 42 (42) | 39 (39) | 0.86 |

| Thiazide | 12 (12) | 16 (16) | 15 (15) | 0.72 |

| ACE inhibitor | 52 (53) | 56 (57) | 55 (56) | 0.88 |

| Angiotensin-R blocker | 34 (35) | 35 (35) | 43 (43) | 0.37 |

| Colchicine | 5 (5) | 5 (5) | 7 (7) | 0.78 |

| EPO | 6 (6) | 1 (1) | 6 (6) | 0.13 |

| Insulin | 26 (27) | 24 (24) | 30 (30) | 0.62 |

| Oral diabetes medicationa | 21 (21) | 21 (21) | 17 (17) | 0.70 |

| Diabetes with microalbuminuriab | 16 (16) | 8 (8) | 16 (17) | 0.16 |

| Diabetes with macroalbuminuriab | 24 (25) | 29 (30) | 21 (22) | 0.41 |

| Cardiovascular diseasec | 8 (8) | 9 (9) | 7 (7) | 0.87 |

| Laboratory measures | ||||

| Hemoglobin A1C, % | 6.8 (1.9) | 6.4 (1.2) | 6.4 (1.3) | 0.09 |

| Cholesterol, mg/dl | 175.7 (63.9) | 168.6 (50.7) | 169.8 (52.0) | 0.63 |

| C-reactive protein, mg/L | 6.2 (10.0) | 5.6 (8.5) | 4.9 (6.9) | 0.58 |

| CO2 (bicarbonate), mmol/L | 24.7 (3.6) | 24.73 (3.4) | 24.9 (3.6) | 0.93 |

| Fractional excretion phosphorus, % | 29.4 (16.1) | 29.40 (13.2) | 29.0 (19.0) | 0.98 |

| Fractional excretion uric acid, % | 7.0 (3.9) | 7.06 (4.0) | 6.9 (6.9) | 0.96 |

| Fractional excretion calcium, % | 1.3 (1.2) | 1.37 (2.5) | 1.2 (1.4) | 0.78 |

| Fractional excretion sodium, % | 1.6 (1.5) | 1.57 (1.2) | 1.6 (1.5) | 0.94 |

| Fractional excretion potassium, % | 15.9 (15.1) | 14.82 (10.1) | 13.8 (9.4) | 0.45 |

| Albumin excretion rate (mg/d), median (IQR) | 340 (56–913) | 175 (18–982) | 82 (16–921) | 0.01d |

H2, histamine H2 antagaonist; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; EPO, erythropoetin.

Oral diabetes medications were metformin or sulfonylurea.

Prevalent diabetes was on the basis of self-report, physician diagnosis, use of diabetes medications, or fasting glucose.

Cardiovascular disease was defined as coronary artery disease, heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, or cerebrovascular disease.

Test for trend of median albumin excretion rate over categories of clearance on the basis of quantile regression.

During a median of 3.0 years of follow-up (IQR, 1.8–4.0 years), there were 43 deaths (5.1 deaths per 100 person-years). The lowest tertile of estimated net HA clearance was associated with a greater risk of death after adjustment for age, sex, race, and filtration function (Table 4) (hazard ratio, 2.5; 95% confidence interval, 1.2 to 5.5 comparing the lowest tertile with the highest tertile); PCS was similarly associated (hazard ratio, 2.5; 95% confidence interval, 1.0 to 6.1). Categories of net clearances of CMG and IS were not significantly associated with mortality. During a similar follow-up period (median, 2.8 years; IQR, 1.6–3.8 years), 20 participants initiated chronic dialysis (2.5 events per 100 person-years). Lower estimated net CMG clearance was associated with a greater risk of dialysis initiation (hazard ratio, 3.3); however, the confidence interval (0.7 to 15.7) was wide and included the null. Clearances of HA, IS, and PCS were not associated with progression to ESRD in this cohort. Secondary analyses with adjustment for components of the Tangri model (age, sex, eGFR, macroalbuminuria, and serum calcium, phosphorus, bicarbonate, and albumin), diabetes, or albumin excretion (Supplemental Material) yielded substantively similar results.

Table 4.

Net secretion and events comparing categories of solute clearance relative to average urea and creatinine clearance

| Secreted Solute Function Category | No. of Events | Incidence per 100 person-yr (95% CI)a | Hazard Ratio (95% CI)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| HA | |||

| Outcome: death | |||

| HA: low (versus high) | 19 | 6.8 (3.8 to 9.9) | 2.5 (1.2 to 5.5) |

| HA: medium (versus high) | 12 | 4.4 (2.1 to 7.0) | 1.1 (0.5 to 2.5) |

| HA: high (referent) | 11 | 3.8 (1.8 to 6.6) | Reference |

| Outcome: dialysisa | |||

| HA: low (versus high) | 7 | 2.7 (0.9 to 4.8) | 1.5 (0.3 to 6.7) |

| HA: medium (versus high) | 7 | 2.6 (0.9 to 4.8) | 1.1 (0.4 to 3.0) |

| HA: high (referent) | 6 | 2.1 (0.7 to 4.4) | Reference |

| CMG | |||

| Outcome: deatha | |||

| CMG: low (versus high) | 12 | 4.4 (2.1 to 7.0) | 1.0 (0.5 to 2.1) |

| CMG: medium (versus high) | 16 | 5.8 (3.1 to 8.7) | 1.0 (0.5 to 2.1) |

| CMG: high (referent) | 15 | 5.1 (2.8 to 8.3) | Reference |

| Outcome: dialysisa | |||

| CMG: low (versus high) | 9 | 3.5 (1.4 to 5.7) | 3.3 (0.7 to 15.7) |

| CMG: medium (versus high) | 6 | 2.3 (0.7 to 4.4) | 1.1 (0.3 to 4.5) |

| CMG: high (referent) | 4 | 1.4 (0.4 to 3.4) | Reference |

| PCS | |||

| Outcome: deatha | |||

| PCS: low (versus high) | 14 | 5.6 (3.3 to 9.4) | 2.5 (1.0 to 6.1) |

| PCS: medium (versus high) | 17 | 6.0 (3.7 to 9.6) | 1.3 (0.6 to 3.1) |

| PCS: high (referent) | 11 | 4.0 (2.2 to 7.2) | Reference |

| Outcome: dialysisa | |||

| PCS: low (versus high) | 9 | 3.8 (2.0 to 7.3) | 0.9 (0.2 to 4.0) |

| PCS: medium (versus high) | 7 | 2.5 (1.2 to 5.3) | 1.3 (0.3 to 5.4) |

| PCS: high (referent) | 4 | 1.5 (0.6 to 3.9) | Reference |

| IS | |||

| Outcome: deatha | |||

| IS: low (versus high) | 12 | 4.8 (2.7 to 8.4) | 1.1 (0.5 to 2.5) |

| IS: medium (versus high) | 14 | 4.8 (2.8 to 8.0) | 0.6 (0.3 to 1.3) |

| IS: high (referent) | 16 | 6.0 (3.7 to 9.8) | Reference |

| Outcome: dialysisa | |||

| IS: low (versus high) | 9 | 3.8 (2.0 to 7.4) | 1.1 (0.2 to 7.1) |

| IS: medium (versus high) | 8 | 2.8 (1.4 to 5.6) | 1.8 (0.3 to 9.7) |

| IS: high (referent) | 3 | 1.1 (0.4 to 3.5) | Reference |

95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

95% CIs calculated from Poisson distribution.

Cox proportional hazards models comparing categories of net tubular solute clearance adjusted for age, sex, black race, other nonwhite race, urea and creatinine clearance, and albumin excretion rate.

Discussion

In summary, we estimated proximal tubular solute clearance on the basis of the clearances of four solutes in a cohort of 298 patients with CKD. We found modest correlation of these secreted solute clearances with filtration estimated by the average of creatinine and urea clearance. Our findings suggest considerable interindividual differences in tubular secretion versus glomerular filtration in the setting of CKD. Women tended to have lower net secreted solute clearances compared with men. Within constraints of a small number of events, lower net solute clearance was also associated with greater risk of mortality.

Proximal tubule secretion has long been recognized as an essential renal mechanism for the elimination of endogenous organic anions and drugs.20 Unique properties that distinguish proximal tubule secretion from GFR include the ability to rapidly clear metabolites from the circulation, the capacity to excrete protein-bound solutes, and the central physiologic role in renal drug clearance.4,21 The capacity for rapid solute excretion is shown by substantially greater clearances of proximal tubule substrates compared with those of creatinine or other filtered substances.

The large observed interindividual variation in secreted solute clearances relative to creatinine and urea clearance suggests that glomerular filtration and proximal tubular secretion may decline at different rates among individuals with CKD. In this context, the measurement of proximal tubule solute clearance may add complementary information to GFR for evaluating CKD complications and long-term outcomes and optimizing medication dosing. Given the direct role of tubular secretion in the renal elimination of hundreds of common drugs, quantification of tubular secretion may be particularly important for determining medication dosing strategies in kidney disease and aging.

It is possible that different secretory solutes may represent distinct facets of tubular secretion. For example, despite being members of related metabolic pathways,22 HA and CMG were not consistently associated with the same characteristics, risk factors, and outcomes, and they were not strongly correlated with each other. Although HA is a known substrate of organic anion transporters 1 and 3, specific mechanisms of CMG transport are unknown.21,23 Biologic variability in protein expression of different transporters—such as in diabetes24—may contribute to the observed intraindividual variability of different secretory solutes.

PCS and IS are gut-derived metabolites and excreted less among vegetarians than among carnivores, suggesting a dietary component to serum accumulation and variability.19 Because these two solutes are less well cleared than HA and CMG25 and because their excretion variability correlates strongly with filtration, they may not represent independent secretory solutes, despite having somewhat more a priori information regarding their primary transporters.18,26,27 They may also be subject to a high degree of protein binding, reducing availability for proximal tubule transport and thereby, possibly leading to measurement error in solute clearance.

Previous studies have reported associations of higher serum concentrations of IS and PCS with mortality, cardiovascular disease, and progression of kidney disease28; proposed mechanisms to explain this toxicity include effects on cardiac myocytes and endothelial cells.29 Little is known about potential toxicity of CMG and HA, and to our knowledge, our study is the first to evaluate associations of the renal clearances of any secreted solutes with clinical outcomes.

This study includes several important limitations. First, measurement error in determining solute concentrations in serum and urine may have falsely exaggerated the amount of variation in net proximal tubular solute clearances relative to filtration. Potential sources of measurement error include within–individual biologic fluctuations in serum concentrations, violating the steady-state assumption for clearance calculations; moderately high assay variation for urine measurements; and imprecision in urine collection times. Presumably, differences between misclassified and true clearances of these solutes are nonsystematic, potentially contributing to null associations. We attempted to address imprecision in urine collection times by comparing tubule solute clearances with creatinine and urea clearance from the same timed sample. Additional studies are needed to specifically confirm or refute the assumption of steady–state blood concentrations of these markers and other endogenous secretion markers within an individual over a typical timed urine collection period. Second, we did not perform gold standard measurements of filtration or secretion using exogenous markers, such as iodothalamate or para–amino-HA. Third, ≤30% of creatinine excretion may occur by secretion, creating some overlap with estimated net clearances of proximal tubule solutes. We used the average of creatinine and urea clearance to lessen the potential effect of creatinine secretion. Fourth, the small sample size and small number of mortality and incident dialysis events may have contributed to low study sensitivity (false null) in detecting associations between net secretion and patient characteristics and with risk of outcomes. Analytic replication in larger studies may correct such errors. Fifth, we estimated proximal tubule solute clearance using only four markers; addition of other secreted metabolites may improve the prediction of secretion function.

In summary, this study shows the first characterization of proximal tubular secretion as an independent marker of kidney function in a longitudinal cohort of patients with CKD. These data motivate additional investigation of tubular secretion as a measure of kidney function, with potential applications in distinguishing disease processes of CKD, improving prediction of CKD complications and outcomes, and refining renal drug dosing strategies.

Concise Methods

Study Population

The Seattle Kidney Study (SKS) is a clinic–based, prospective cohort study of CKD.30,31 From 2004 to the present, the SKS has recruited 691 patients from nephrology clinics at the Veteran’s Administration Puget Sound Health Care System, the Harborview Medical Center, and the University of Washington Medical Center (all in Seattle, WA). Patients were eligible for the SKS if they had any stage of CKD, were at least 18 years old, and were not receiving any form of RRT. General SKS exclusion criteria included dementia, residency in an institution, inability to provide informed consent, non-English speaking, or expecting to initiate dialysis within 6 months.

Serum and timed overnight urine samples (median of 12 hours; IQR, 11–14 hours) were collected at baseline and follow-up clinic visits among a subset of SKS participants. For inclusion into this ancillary study, we required study visits that had available timed urine overnight and corresponding next morning serum samples. We excluded urine samples deemed inadequate on the basis of (1) collection time <8 or >36 hours, (2) urine volume <250 ml or >10 L, or (3) a 24-hour standardized urine creatinine excretion <8 mg/kg lean body mass (LBM) for women or <10 mg/kg LBM for men. We also excluded participants who had nephrotic-range proteinuria (urine albumin-creatinine ratio >3000 mg/g) because of uncertainty regarding effects on urine secretion measurements. For participants with multiple eligible clinic visits, we selected the first available visit. Extreme outliers with unreasonable values for secretion were excluded from the primary analyses, although sensitivity analyses did include them (final n=298 for HA and CMG; final n=291 for PCS and IS). Serum and urine samples were collected between 2007 and 2010; aliquots were stored at −80°C until assay. Analytes were empirically determined as stable in both serum and urine samples stored at −20°C over 5 months of assay development.

Measurement of Exposures

HA, CMG, PCS, and IS were selected as candidate markers for secretion on the basis of a list constructed from several lines of published evidence, including substrate of known proximal tubule transporters, urinary clearance substantially greater than that of filtration markers (e.g., creatinine), and minimal elimination by other organ systems; final candidates were selected from this list on the basis of commercial availability of standards and reproducible protocols for the MS assays. Serum solute measurements were of total concentration: samples were extracted using formic acid/acetonitrile as part of the protein precipitation step of liquid chromatography-MS/MS assays, which removes all bound solutes from serum proteins. Residual protein remnants were removed by filtration and evaporation and then, discarded. The extracted serum was reconstituted in water for subsequent MS/MS quantification. Timed urine solutes were quantified using similar methods without the protein precipitation steps. Isotope dilution with stable isotope–labeled internal standards and external calibration materials maximized precision. Fragment ion ratios were monitored for specificity. Matrix effects were minimal at low concentrations of analytes for both urine and serum samples as determined by dilution and parallelism experiments. Over 8 months of assay performance, total interassay variability (coefficient of variation [CV]) was 5.6%–12.6% CV for CMG in serum, 7.1%–9.0% CV for HA in serum, and 20.3% CV for both in urine. Assay variability was validated as <20% at 0.3 and 600 µg/ml in serum/plasma and 4.0 and 1,000 µg/ml in urine for CMG and HA, respectively.

To assess repeatability of tubule solute clearances within an individual, we obtained paired plasma and 24-hour urine samples from a dietary study of 25 healthy overweight volunteers (mean age of 39 years; mean body mass index of 30 kg/m2; 60% women). Paired plasma and urine samples were obtained at baseline, 2 weeks, and 12 weeks. Mean within–individual CVs for the clearances of HA, CMG, PCS, and IS across these three study visits were 34.8%, 36.0%, 34.4%, and 25.5%.

Creatinine and urea were measured from the same paired set of serum and urine samples used for proximal tubule solute measurements using the Jaffe method (creatinine) and enzymatic conductivity on the Beckman Coulter DXC Automated Platform (urea; Beckman Coulter, Inc., Brea CA).

Measurement of Outcomes

The SKS coordinators identified the initiation of chronic dialysis and deaths by annual examinations, surveillance telephone and scheduling calls, and use of the national Social Security death index.

Measurement of Other Study Data

We estimated GFR using the serum creatinine–based 2009 CKD-EPI equation.32 We measured urine albumin concentration using immunoturbidimetry and multiplied this value by urine collection volume over 24 hours to estimate daily urine albumin excretion. The SKS participants self-reported their age, sex, race (categorized in this study as white, black, or other), current smoking status, current alcohol use, and prevalent medication conditions through annual questionnaires. Coordinators determined medication use by the inventory method. We defined prevalent diabetes by participant self-report of diabetes, use of any diabetes medication, hemoglobin A1C value ≥6.5%, a fasting blood glucose ≥126 mg/dl, or a nonfasting blood glucose ≥200 mg/dl. Coordinators measured BP using an automated sphygmometer. LBM was estimated using the Hume formula.

Statistical Analyses

We calculated the clearances of HA, CMG, PCS, IS, creatinine, and urea as the volume of blood fully cleared per minute:

where Ux is the urinary concentration of solute X, Px is the total serum concentration of solute X, and V is the urine volume over the collection period.33 We averaged the clearance of creatinine and urea to estimate filtration as previously described.34

Individual distributions of HA, CMG, PCS, IS, creatinine, and urea clearance were tabulated using summary statistics. Joint distributions of these clearances were estimated using scatter plots and Pearson correlation coefficients. To categorize estimated secretion function, HA, CMG, PCS, and IS clearances were regressed over creatinine and urea clearance using quantile regression at the 33rd and 67th percentiles. This approach stratified the cohort into tertiles of low, medium, and high secretion function relative to filtration (net secretion). Participant characteristics were examined according to net secretion categories and tested for linear trend. Secondary linear regressions (Supplemental Material) included adjustment for age, sex, race, eGFR, and LBM–standardized daily creatinine excretion.

We used Cox proportional hazards regressions with robust SEM estimation to estimate the associations of net secretion categories with the time to mortality and dialysis events. Censoring events included loss to follow-up, death, or end of study period (January 1, 2012). Sensitivity analyses evaluated initiation of dialysis with death included as a competing risk using the method by Fine and Gray.35 Primary adjustments included age, sex, race, creatinine and urea clearance, and albumin excretion rate; secondary analyses adjusted for components of the Tangri risk model of progression to ESRD, including age, sex, eGFR, macroalbuminuria, and serum calcium, phosphorus, bicarbonate, and albumin.36 The proportional hazards assumption for Cox models was evaluated by visual inspection of log-log plots.

All analyses were performed using Stata (version 13; StataCorp., College Station, TX).

Disclosures

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases R01DK 094891 (to B.R.K.).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2014121193/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Levey AS, de Jong PE, Coresh J, El Nahas M, Astor BC, Matsushita K, Gansevoort RT, Kasiske BL, Eckardt KU: The definition, classification, and prognosis of chronic kidney disease: A KDIGO Controversies Conference report. Kidney Int 80: 17–28, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levey AS, Eckardt KU, Tsukamoto Y, Levin A, Coresh J, Rossert J, De Zeeuw D, Hostetter TH, Lameire N, Eknoyan G: Definition and classification of chronic kidney disease: A position statement from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int 67: 2089–2100, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eknoyan G, Hostetter T, Bakris GL, Hebert L, Levey AS, Parving HH, Steffes MW, Toto R: Proteinuria and other markers of chronic kidney disease: A position statement of the national kidney foundation (NKF) and the national institute of diabetes and digestive and kidney diseases (NIDDK). Am J Kidney Dis 42: 617–622, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sirich TL, Aronov PA, Plummer NS, Hostetter TH, Meyer TW: Numerous protein-bound solutes are cleared by the kidney with high efficiency. Kidney Int 84: 585–590, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Astor BC, Matsushita K, Gansevoort RT, van der Velde M, Woodward M, Levey AS, Jong PE, Coresh J, Astor BC, Matsushita K, Gansevoort RT, van der Velde M, Woodward M, Levey AS, de Jong PE, Coresh J, El-Nahas M, Eckardt KU, Kasiske BL, Wright J, Appel L, Greene T, Levin A, Djurdjev O, Wheeler DC, Landray MJ, Townend JN, Emberson J, Clark LE, Macleod A, Marks A, Ali T, Fluck N, Prescott G, Smith DH, Weinstein JR, Johnson ES, Thorp ML, Wetzels JF, Blankestijn PJ, van Zuilen AD, Menon V, Sarnak M, Beck G, Kronenberg F, Kollerits B, Froissart M, Stengel B, Metzger M, Remuzzi G, Ruggenenti P, Perna A, Heerspink HJ, Brenner B, de Zeeuw D, Rossing P, Parving HH, Auguste P, Veldhuis K, Wang Y, Camarata L, Thomas B, Manley T Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium : Lower estimated glomerular filtration rate and higher albuminuria are associated with mortality and end-stage renal disease. A collaborative meta-analysis of kidney disease population cohorts. Kidney Int 79: 1331–1340, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gansevoort RT, Matsushita K, van der Velde M, Astor BC, Woodward M, Levey AS, de Jong PE, Coresh J Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium : Lower estimated GFR and higher albuminuria are associated with adverse kidney outcomes. A collaborative meta-analysis of general and high-risk population cohorts. Kidney Int 80: 93–104, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Velde M, Matsushita K, Coresh J, Astor BC, Woodward M, Levey A, de Jong P, Gansevoort RT, van der Velde M, Matsushita K, Coresh J, Astor BC, Woodward M, Levey AS, de Jong PE, Gansevoort RT, Levey A, El-Nahas M, Eckardt KU, Kasiske BL, Ninomiya T, Chalmers J, Macmahon S, Tonelli M, Hemmelgarn B, Sacks F, Curhan G, Collins AJ, Li S, Chen SC, Hawaii Cohort KP, Lee BJ, Ishani A, Neaton J, Svendsen K, Mann JF, Yusuf S, Teo KK, Gao P, Nelson RG, Knowler WC, Bilo HJ, Joosten H, Kleefstra N, Groenier KH, Auguste P, Veldhuis K, Wang Y, Camarata L, Thomas B, Manley T Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium : Lower estimated glomerular filtration rate and higher albuminuria are associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. A collaborative meta-analysis of high-risk population cohorts. Kidney Int 79: 1341–1352, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peralta CA, Shlipak MG, Judd S, Cushman M, McClellan W, Zakai NA, Safford MM, Zhang X, Muntner P, Warnock D: Detection of chronic kidney disease with creatinine, cystatin C, and urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio and association with progression to end-stage renal disease and mortality. JAMA 305: 1545–1552, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abboud H, Henrich WL: Clinical practice. Stage IV chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 362: 56–65, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindeman RD, Tobin J, Shock NW: Longitudinal studies on the rate of decline in renal function with age. J Am Geriatr Soc 33: 278–285, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brenner BM, Meyer TW, Hostetter TH: Dietary protein intake and the progressive nature of kidney disease: The role of hemodynamically mediated glomerular injury in the pathogenesis of progressive glomerular sclerosis in aging, renal ablation, and intrinsic renal disease. N Engl J Med 307: 652–659, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meyer TW, Walther JL, Pagtalunan ME, Martinez AW, Torkamani A, Fong PD, Recht NS, Robertson CR, Hostetter TH: The clearance of protein-bound solutes by hemofiltration and hemodiafiltration. Kidney Int 68: 867–877, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amorim LC, Alvarez-Leite EM: Determination of o-cresol by gas chromatography and comparison with hippuric acid levels in urine samples of individuals exposed to toluene. J Toxicol Environ Health 50: 401–407, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyer TW, Hostetter TH: Uremia. N Engl J Med 357: 1316–1325, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rhee EP, Souza A, Farrell L, Pollak MR, Lewis GD, Steele DJ, Thadhani R, Clish CB, Greka A, Gerszten RE: Metabolite profiling identifies markers of uremia. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1041–1051, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mulder TP, Rietveld AG, van Amelsvoort JM: Consumption of both black tea and green tea results in an increase in the excretion of hippuric acid into urine. Am J Clin Nutr 81[Suppl]: 256S–260S, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martinez AW, Recht NS, Hostetter TH, Meyer TW: Removal of P-cresol sulfate by hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 3430–3436, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deguchi T, Ohtsuki S, Otagiri M, Takanaga H, Asaba H, Mori S, Terasaki T: Major role of organic anion transporter 3 in the transport of indoxyl sulfate in the kidney. Kidney Int 61: 1760–1768, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel KP, Luo FJ, Plummer NS, Hostetter TH, Meyer TW: The production of p-cresol sulfate and indoxyl sulfate in vegetarians versus omnivores. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 982–988, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grantham JJCA, editor: Renal Handling of Organic Anions and Cations; Metabolism and Excretion of Uric Acid, Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1986 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anzai N, Kanai Y, Endou H: Organic anion transporter family: Current knowledge. J Pharmacol Sci 100: 411–426, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoskins JA, Holliday SB, Greenway AM: The metabolism of cinnamic acid by healthy and phenylketonuric adults: A kinetic study. Biomed Mass Spectrom 11: 296–300, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsutsumi Y, Deguchi T, Takano M, Takadate A, Lindup WE, Otagiri M: Renal disposition of a furan dicarboxylic acid and other uremic toxins in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 303: 880–887, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phatchawan A, Chutima S, Varanuj C, Anusorn L: Decreased renal organic anion transporter 3 expression in type 1 diabetic rats. Am J Med Sci 347: 221–227, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poesen R, Viaene L, Verbeke K, Claes K, Bammens B, Sprangers B, Naesens M, Vanrenterghem Y, Kuypers D, Evenepoel P, Meijers B: Renal clearance and intestinal generation of p-cresyl sulfate and indoxyl sulfate in CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 1508–1514, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akiyama Y, Kikuchi K, Saigusa D, Suzuki T, Takeuchi Y, Mishima E, Yamamoto Y, Ishida A, Sugawara D, Jinno D, Shima H, Toyohara T, Suzuki C, Souma T, Moriguchi T, Tomioka Y, Ito S, Abe T: Indoxyl sulfate down-regulates SLCO4C1 transporter through up-regulation of GATA3. PLoS One 8: e66518, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohtsuki S, Asaba H, Takanaga H, Deguchi T, Hosoya K, Otagiri M, Terasaki T: Role of blood-brain barrier organic anion transporter 3 (OAT3) in the efflux of indoxyl sulfate, a uremic toxin: Its involvement in neurotransmitter metabolite clearance from the brain. J Neurochem 83: 57–66, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin CJ, Wu V, Wu PC, Wu CJ: Meta-analysis of the associations of p-cresyl sulfate (PCS) and indoxyl sulfate (IS) with cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in patients with chronic renal failure. PLoS One 10: e0132589, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vanholder R, Schepers E, Pletinck A, Nagler EV, Glorieux G: The uremic toxicity of indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate: A systematic review. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 1897–1907, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robinson-Cohen C, Littman AJ, Duncan GE, Roshanravan B, Ikizler TA, Himmelfarb J, Kestenbaum BR: Assessment of physical activity in chronic kidney disease. J Ren Nutr 23: 123–131, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robinson-Cohen C, Littman AJ, Duncan GE, Weiss NS, Sachs MC, Ruzinski J, Kundzins J, Rock D, de Boer IH, Ikizler TA, Himmelfarb J, Kestenbaum BR: Physical activity and change in estimated GFR among persons with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 399–406, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doolan PD, Alpen EL, Theil GB: A clinical appraisal of the plasma concentration and endogenous clearance of creatinine. Am J Med 32: 65–79, 1962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levey AS: Measurement of renal function in chronic renal disease. Kidney Int 38: 167–184, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fine J, Gray R: A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 94: 496–509, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tangri N, Stevens LA, Griffith J, Tighiouart H, Djurdjev O, Naimark D, Levin A, Levey AS: A predictive model for progression of chronic kidney disease to kidney failure. JAMA 305: 1553–1559, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.