Abstract

Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) is a methyltransferase that induces histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K27me3) and functions as an oncogenic factor in many cancer types. However, the role of EZH2 in renal fibrogenesis remains unexplored. In this study, we found high expression of EZH2 and H3K27me3 in cultured renal fibroblasts and fibrotic kidneys from mice with unilateral ureteral obstruction and humans with CKD. Pharmacologic inhibition of EZH2 with 3-deazaneplanocin A (3-DZNeP) or GSK126 or siRNA-mediated silencing of EZH2 inhibited serum- and TGFβ1-induced activation of renal interstitial fibroblasts in vitro, and 3-DZNeP administration abrogated deposition of extracellular matrix proteins and expression of α-smooth muscle actin in the obstructed kidney. Injury to the kidney enhanced Smad7 degradation, Smad3 phosphorylation, and TGFβ receptor 1 expression, and 3-DZNeP administration prevented these effects. 3-DZNeP also suppressed phosphorylation of the renal EGF and PDGFβ receptors and downstream signaling molecules signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 and extracellular signal–regulated kinase 1/2 after injury. Moreover, EZH2 inhibition increased the expression of phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), a protein previously associated with dephosphorylation of tyrosine kinase receptors in the injured kidney and serum–stimulated renal interstitial fibroblasts. Finally, blocking PTEN with SF1670 largely diminished the inhibitory effect of 3-DZNeP on renal myofibroblast activation. These results uncovered the important role of EZH2 in mediating the development of renal fibrosis by downregulating expression of Smad7 and PTEN, thus activating profibrotic signaling pathways. Targeted inhibition of EZH2, therefore, could be a novel therapy for treating CKD.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, fibrosis, obstructive nephropathy, fibroblast, signaling

CKD is characterized by the activation of renal interstitial fibroblasts and deposition of excessive amounts of extracellular matrix (ECM) components. This leads to distortion of the renal architecture, progressive loss of renal function, and ultimately, renal failure. Differentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts is characterized by expression of a high level of both α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and fibronectin.1–4 A wide variety of growth factors and cytokine receptors, such as TGFβ receptor, PDGF receptor (PDGFR),5 and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR),6,7 can activate renal fibroblasts and promote the development and progression of renal fibrosis. TGFβ receptor activation leads to initiation of several intracellular signaling pathways, including mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 3 (Smad3),8 signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3),9 and extracellular signal–regulated kinase 1 and 2 (ERK1/2).10,11 Stimulation of PDGFR and EGFR also induces activation of STAT3 and ERK1/2 signaling pathways.12,13 In contrast, induction of phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) and/or peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor-γ can interfere with activation of multiple profibrotic signaling pathways, leading to tissue fibrosis inhibition.14

Epigenetics, which refers to the modulation of gene expression through post-translational modification of protein complexes associated with DNA without changing the DNA sequence, have been shown to play a role in the expression of profibrotic genes and the regulation of renal fibrogenesis.15,16 These modifications can alter and influence the accessibility for transcription factor binding, thereby regulating gene transcription and cellular functions.17–20 There are several protein/histone modifications, including acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and sumoylation. Studies from our group and others have shown that histone acetylation and DNA methylation contribute to the activation of renal interstitial fibroblasts and the development and progression of renal fibrosis.21,22 The role of other histone modifications, in particular histone methylation, in the regulation of these processes remains unknown.

Unlike acetylation, histone methylation does not change the lysine charge but alters transcription by providing docking sites for chromatin modifiers. Lysine residues of histone proteins can be mono-, di-, and trimethylated. This process is regulated by both histone lysine methyltransferases and histone demethylases. The histone methyltransferase enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) mediates trimethylation of histone H3 at lysine27 (H3K27me3).23 EZH2 is the functional component of the polycomb repressive complex 2, which contains multiple proteins for its optimal function.24 In this complex, EZH2 is responsible for the methylation activity of polycomb repressive complex 2.25 H3K27me3 is a transcriptionally repressive epigenetic marker that has been associated with suppression of multiple tumor suppressor genes,26,27 and EZH2 overexpression is observed in many aggressive tumors with poor outcomes.28–30 Its downregulation reduces growth of invasive breast carcinoma31 and inhibits tumor angiogenesis.32 In addition, depletion of cellular levels of EZH2 by treatment with 3-deazaneplanocin A (3-DZNeP), a carbocyclic analog of adenosine, also inhibits H3K27me3.33 Currently, this compound is widely used in preclinical and in vitro studies to investigate the function of EZH2 in cancer and has been shown to effectively inhibit cell proliferation, reverse epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, and prevent tumor progression.34 However, it remains unclear whether targeting suppression of EZH2 can also interfere with renal interstitial fibroblast activation and renal fibrosis development.

In this study, we examined the effect of pharmacologic EZH2 inhibition on the activation of cultured renal interstitial fibroblasts and the development and progression of renal fibrosis in a mouse model of unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO). Our results indicated that EZH2 is highly expressed in the activated renal interstitial fibroblasts (myofibroblasts) and fibrotic kidneys. Downregulation of EZH2 resulted in suppression of myofibroblast activation and attenuation of renal fibrogenesis by blocking multiple profibrotic signaling pathways.

Results

3-DZNeP Inhibits Serum–Induced Renal Interstitial Fibroblast Activation

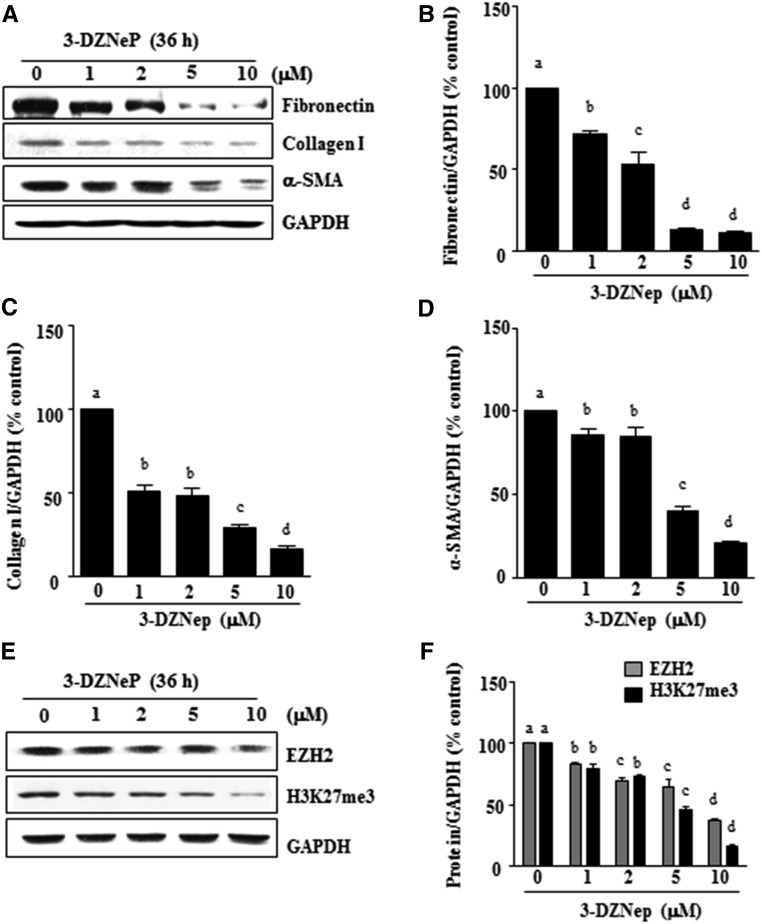

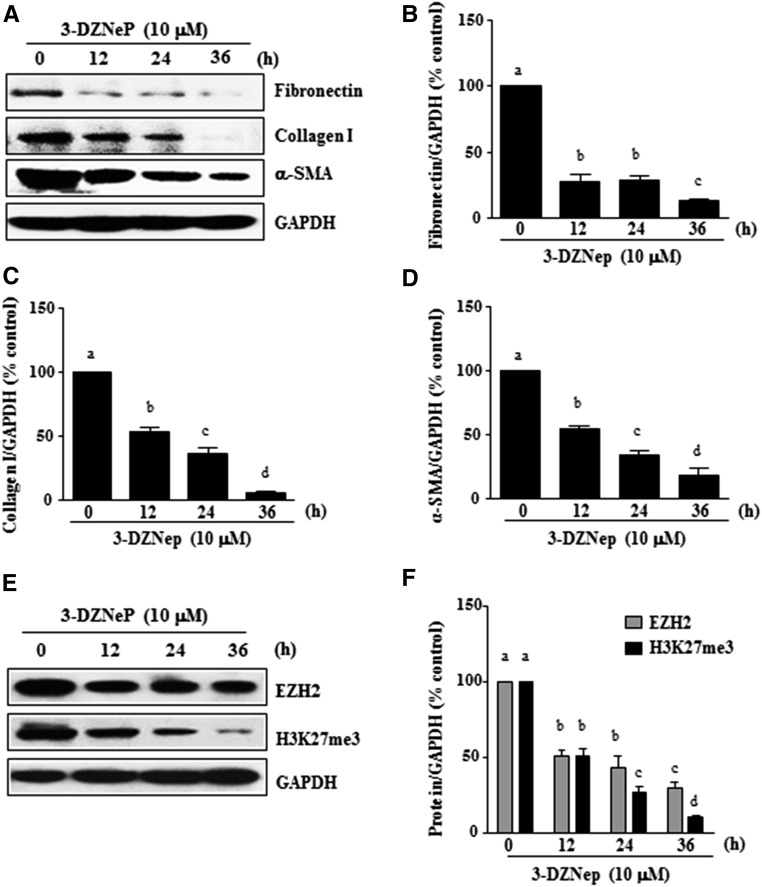

Development and progression of renal fibrosis depend predominantly on activation of renal fibroblasts and subsequent deposition of ECM.35,36 To examine whether EZH2 is involved in renal fibroblast activation, normally cultured rat renal interstitial fibroblast cells (NRK-49F) were exposed to various concentrations of 3-DZNeP, a selective inhibitor for EZH2 that induces EZH2 degradation.33 As shown in Figure 1, 3-DZNeP dose dependently inhibited the expression of α-SMA, the hallmark of fibroblast activation, as well as collagen I and fibronectin, two major ECM proteins. Densitometry analysis of the immunoblot results showed that 3-DZNeP reduced expressions of α-SMA, fibronectin, and collagen I by approximately 60%, 70%, and 70%, respectively, at a dose of 10 μM (Figure 1, A–D). The time course study with 10 μM of 3-DZNeP showed a significant decrease in the expression level of α-SMA at 12 hours; it was further decreased by more than twofold at 36 hours. Similarly, 3-DZNeP time dependently suppressed the expression of fibronectin and collagen I, with a complete inhibition at 36 hours (Figure 2, A–D).

Figure 1.

3-DZNeP inhibits renal fibroblast activation in a dose-dependent manner. (A and E) Normally cultured NRK-49F cells were treated with 3-DZNeP (0–10 μM) for 36 hours. Then, cell lysates were prepared and subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies against (A) α-SMA, collagen I, fibronectin, or GAPDH or (E) EZH2, H3K27me3, or GAPDH. The levels of (B) fibronectin, (C) type 1 collagen, (D) α-SMA, or (F) EZH2 and H3K27me3 were quantified by densitometry and normalized with GAPDH. Values are the means±SDs of at least three independent experiments. Bars with different letters (a–d) for each molecule are significantly different from one another (P<0.05).

Figure 2.

3-DZNeP inhibits renal fibroblast activation in a time-dependent manner. (A and E) Normally cultured NRK-49F cells were treated with 10 μM 3-DZNeP for the indicated time. Then, cell lysates were prepared and subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies against (A) α-SMA, collagen I, fibronectin, or GAPDH or (E) EZH2, H3K27me3, or GAPDH. The levels of (B) fibronectin, (C) type 1 collagen, (D) α-SMA, or (F) EZH2 and H3K27me3 were quantified by densitometry and normalized with GAPDH. Values are the means±SDs of at least three independent experiments. Bars with different letters (a–d) for each molecule are significantly different from one another (P<0.05).

To ensure that 3-DZNeP–elicited reduction of those fibrotic marker proteins is caused by the inhibition of EZH2 expression and its methyltransferase activity, we examined the effect of 3-DZNeP on the expression of EZH2 and H3K27me3, the major form of methylated histone H3 lysine 27. 3-DZNeP treatment decreased the level of H3K27me3 in a dose- (Figure 1, E and F) and time-dependent manner (Figure 2, E and F). As expected, 3-DZNeP dose and time dependently induced degradation of EZH2 (Figures 1, E and F and 2, E and F). Notably, 3-DZNeP treatment at 10 μM did not cause cleavage of caspase-3, a hallmark of apoptosis, suggesting that it does not induce apoptosis at the highest concentration used in this study. As a positive control, exposure to 1 mM hydrogen peroxide for 4 hours resulted in the expression of the active caspase-3 form in the same culture (Supplemental Figure 1).

Taken together, these results indicate that EZH2 activity is necessary for activation of renal interstitial fibroblasts and that 3-DZNeP, a potent inhibitor of EZH2, attenuates activation of cultured renal interstitial fibroblasts in a time- and dose-dependent manner.

EZH2 Mediates TGFβ1-Induced Activation of Renal Interstitial Fibroblasts

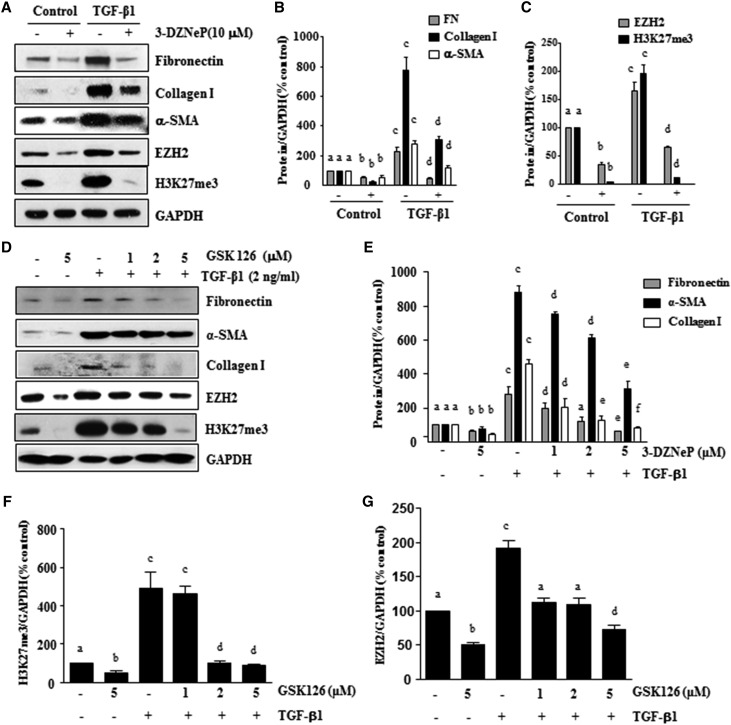

In light of the fact that the cytokine TGFβ1 induces transformation of quiescent renal fibroblasts to myofibroblasts,37 we also examined the effect of EZH2 inhibition on TGFβ1–induced renal fibroblast activation. NRK-49F cells were serum starved for 24 hours and then, exposed to 2 ng/ml TGFβ1 in the absence or presence of 3-DZNeP or GSK126, a highly selective S-adenosyl-methionine–competitive small molecule inhibitor of EZH2.38 As shown in Figure 3, A and B, basal levels of α-SMA, collagen I, and fibronectin were detected in the starved NRK-49F, whereas TGFβ1 treatment remarkably increased expression of those proteins, indicating enhanced fibroblast activation. Treatment of NRK49F with 3-DZNeP inhibited both basal level and TGFβ1-induced expressions of α-SMA, collagen I, and fibronectin. Similar to this observation, treatment with GSK126 also dose dependently reduced TGFβ1-induced expressions of α-SMA, collagen 1, and fibronectin (Figure 3, D and E). Interestingly, TGFβ1 exposure increased the levels of EZH2 and H3K27me3, which were abolished by 3-DZNeP (Figure 3, A and C). GSK126 treatment also reduced the levels of EZH2 and H3K27me3 in a dose-dependent fashion (Figure 3, D, F, and G). In addition, we examined the effect of EZH2 inhibition on the activation of renal fibroblasts induced by PDGF or EGF, two important profibrotic factors, and found that 3-DZNeP and GSK126 had similar inhibitory effects on the expressions of α-SMA, collagen I, and fibronectin in NRK-49F cells (data not shown). These data illustrate that EZH2 inhibitors can suppress activation of renal fibroblast induced by TGFβ1 and other growth factors.

Figure 3.

Treatment with 3-DZNeP or GSK126 inhibits TGFβ1–induced renal fibroblast activation. Serum–starved NRK-49F cells were pretreated with (A–C) 3-DZNeP (10 μM) or (D–G) GSK126 (0–5 μM) for 1 hour and then exposed to TGFβ1 (2 ng/ml) for an additional 24 hours. (A and D) Cell lysates were prepared and subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies against fibronectin, collagen I, α-SMA, EZH2, H3K27me3, or GAPDH. Expression levels of (B and E) fibronectin, collagen I, and α-SMA or (C, F, and G) EZH2 and H3K27me3 were quantified by densitometry and normalized with GAPDH. Values are the means±SDs of at least three independent experiments. Bars with different letters (a–f) are significantly different from one another (P<0.05).

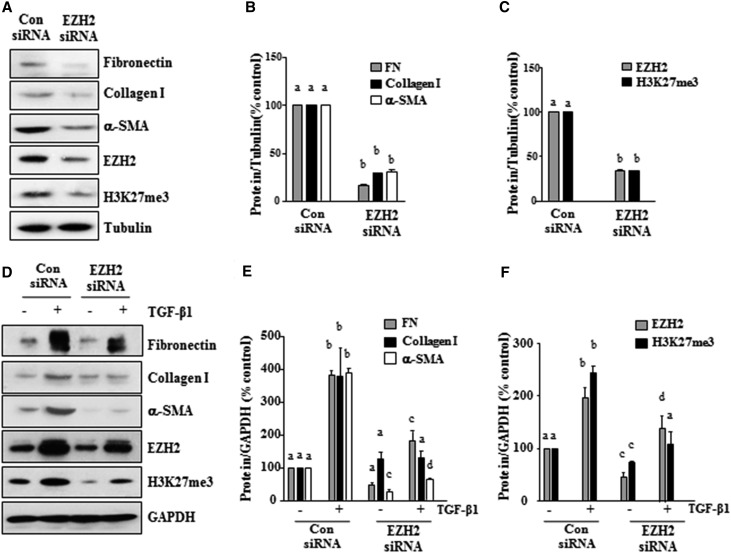

Knockdown of EZH2 Reduces Serum– and TGFβ1–Induced Renal Fibroblast Activation

To confirm the role of EZH2 in renal fibroblast activation, we examined the effect of EZH2 silencing on the expressions of α-SMA, collagen I, and fibronectin in NRK-49F cells. Transfection of NRK-49F cells with specific small interfering RNA (siRNA) for EZH2 resulted in downregulation of EZH2 by approximately 75% (Figure 4, A and C). The EZH2 knockdown significantly decreased the level of H3K27me3 and reduced the serum-induced expressions of α-SMA, collagen I, and fibronectin by three- to fourfold compared with cells transfected with control siRNA (Figure 4, A–C). Interestingly, TGFβ1 increased the levels of EZH2 and H3K27me3 in NRK-49F cells (Figure 4, D and F). Silencing of EZH2 also inhibited the TGFβ1-stimulated expressions of α-SMA, collagen I, and fibronectin (Figure 4, D and E). These results are consistent with the inhibitory effect of 3-DZNeP on renal interstitial fibroblasts and further suggest that EZH2 is involved in the regulation of renal fibroblast activation and the production of ECM proteins.

Figure 4.

Knockdown of EZH2 with siRNA inhibits renal fibroblast activation. Serum–starved NRK-49F cells were transfected with siRNA targeting EZH2 or scrambled siRNA and then, incubated in (A–C) 5% FBS or (D–F) TGFβ1 (2 ng/ml) for an additional 24 hours. (A and D) Cell lysates were prepared for immunoblot analysis with antibodies against fibronectin, collagen I, α-SMA, EZH2, H3K27me3, tubulin or GAPDH. (B, C, E, and F) Expression levels of α-SMA, collagen I, fibronectin, EZH2, or H3K27me3 were quantified by densitometry and normalized with tubulin or GAPDH. Values are the means±SDs of at least three independent experiments. Bars with different letters (a–d) for each molecule are significantly different from one another (P<0.05). FN, fibronectin.

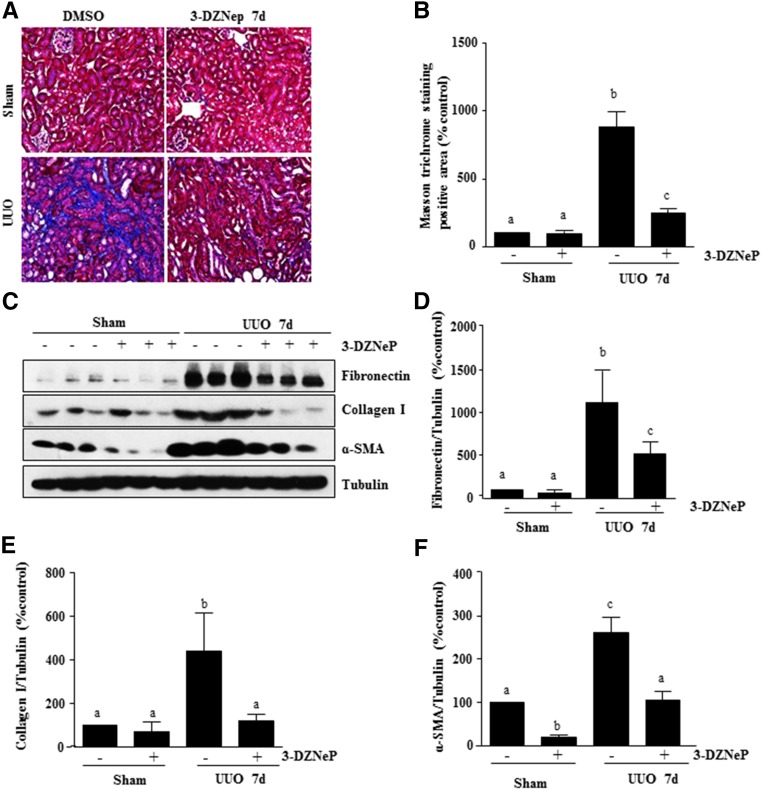

EZH2 Inhibition Attenuates Development of Renal Fibrosis after Obstructed Injury

To assess the role of EZH2 in the development of renal fibrosis, we examined the effect of 3-DZNeP in a murine model of renal fibrosis induced by unilateral ureteric obstruction (UUO). At day 7 after ureteral ureter ligation with or without administration of 3-DZNeP, kidneys were collected and then, subjected to Masson trichrome staining and immunoblots to analyze expression of ECM proteins. As shown in Figure 5, A and B, collagen fibrils are extensively deposited within the interstitial space as a consequence of myofibroblast activation after UUO injury. This was shown by an increase in positive areas of Masson trichrome staining. Semiquantitative analysis of Masson trichrome–positive areas revealed about a threefold increase in deposition of ECM components in the obstructed kidney compared with control kidneys, whereas administration of 3-DZNeP significantly reduced ECM deposition by 80% (Figure 5B). Similar results were also observed in the kidney collected 14 days after ureteral obstruction and treated with 3-DZNeP (Supplemental Figure 2, A and B).

Figure 5.

Administration of 3-DZNeP attenuates development of renal fibrosis and deposition of ECM in obstructed kidneys. (A) Photomicrographs illustrating Masson trichrome staining of kidney tissue (magnification ×200). (B) The Masson trichrome–positive tubulointerstitial area (blue in A) relative to the whole area from ten random cortical fields was analyzed. Data are represented as the means±SDs (n=6). (C) Kidney tissue lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies against α-SMA, collagen 1, fibronectin, or tubulin. Expression levels of fibronectin, collagen 1, α-SMA, or tubulin were quantified by densitometry, and the levels of (D) fibronectin, (E) collagen 1, and (F) α-SMA were normalized with tubulin. Values are the means±SDs (n=6). Means with different letters (a–c) are significantly different from one another (P<0.05).

Activation of renal interstitial fibroblasts and overproduction of ECM proteins are considered central events in the pathogenesis of chronic renal fibrosis.39 To confirm the antifibrotic effect of 3-DZNeP, we further examined the effect of 3-DZNeP on the expression of α-SMA and deposition of fibronectin and collagen type 1 in obstructed kidneys. Immunoblot analysis of whole–kidney tissue lysate indicated that there was a dramatic increase in the expressions of α-SMA, collagen I, and fibronectin in the kidney after 7 days of UUO injury. Administration of 3-DZNeP remarkably decreased the levels of α-SMA (approximately 60%), fibronectin (approximately 60%), and collagen I (approximately 70%) (Figure 5, C–F). Consistent with these results, 3-DZNeP administration was also effective in attenuating expression of these proteins in the kidney collected at 14 days after UUO injury (Supplemental Figure 2, C–F). Taken together, these data indicate that inhibition of EZH2 by 3-DZNeP attenuates development of renal fibrosis after UUO injury.

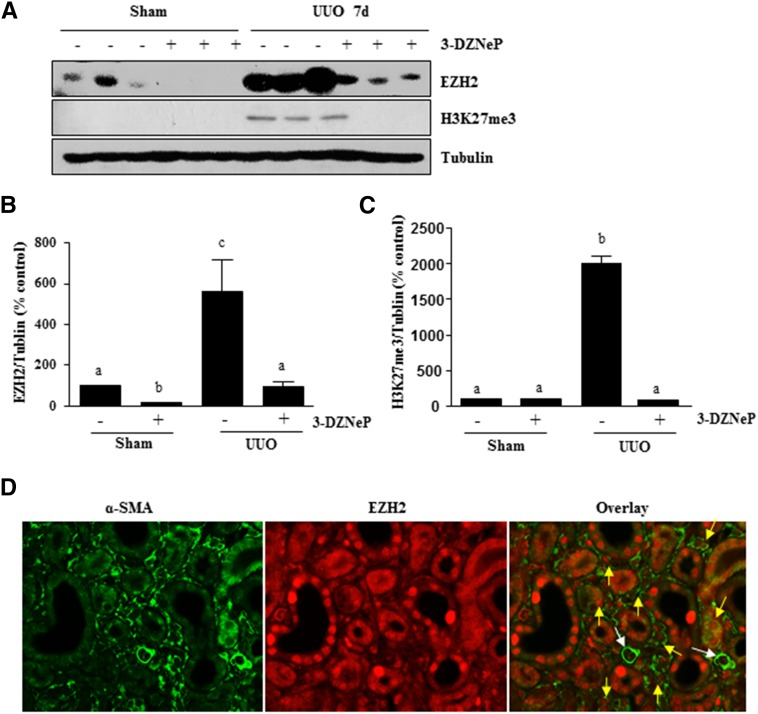

3-DZNeP Inhibits Histone Methylation in the Kidney after Obstructed Injury

To show whether renal fibrosis reduction would be caused by the inhibition of EZH2 activity, we used immunoblot analysis to examine the effect of 3-DZNeP on the expressions of EZH2 and H3K27me3 in the murine kidney collected at 7 and 14 days after UUO. As shown in Figure 6 and Supplemental Figure 3, EZH2 was detectable in the kidney of sham-operated mice, but H3K27me3 was not, suggesting that EZH2 is minimally expressed but not activated in the normal kidney. UUO injury induced a dramatic increase in the expression of renal EZH2, which was accompanied by an increased level of H3K27me3. Administration of 3-DZNeP reduced the expression of EZH2 to the basal level and also, significantly inhibited the increase of H3K27me3 in the kidney of UUO-injured mice. Immunofluorescence staining also showed increased expression of EZH2 in the kidney after UUO injury, and 3-DZNeP treatment reduced its expression. Furthermore, EZH2 is expressed in both renal tubular cells and interstitial myofibroblasts in the injured kidney (Supplemental Figure 4). Expression of EZH2 in myofibroblasts was further shown by its containing with α-SMA (indicated yellow arrows in Figure 6D), but no containing was observed in small blood vessels (indicated by white arrows in Figure 6D). Notably, EZH2 was clearly expressed in both the nucleus and the cytosol of renal tubules and myofibroblasts, whereas only a weak signal of EZH2 was seen in the cytosol of tubules in normal kidneys (Figure 6D, Supplemental Figure 4). These data suggest that EZH2 may be involved in the regulation of profibrotic machinery, at least in both renal fibroblasts and renal tubular cells.

Figure 6.

3-DZNeP effectively inhibits histone methylation in obstructed kidneys. (A) The prepared tissue lysates from sham-operated or obstructed kidneys of mice administered with or without 3-DZNeP were subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies against EZH2, H3K27me3, or tubulin. (B and C) The levels of EZH2, H3K27me3, and tubulin were quantified by densitometry, and EZH2 and H3K27me3 levels were normalized to tubulin. Values are the means±SDs (n=6). Bars with different letters (a–c) are significantly different from one another (P<0.05). (D) Photomicrographs illustrate containing of EZH2 and α-SMA in the tissue section of the obstructed kidney (magnification ×600). Yellow arrows indicate EZH2-positive myofibroblasts, and white arrows indicate small blood vessels.

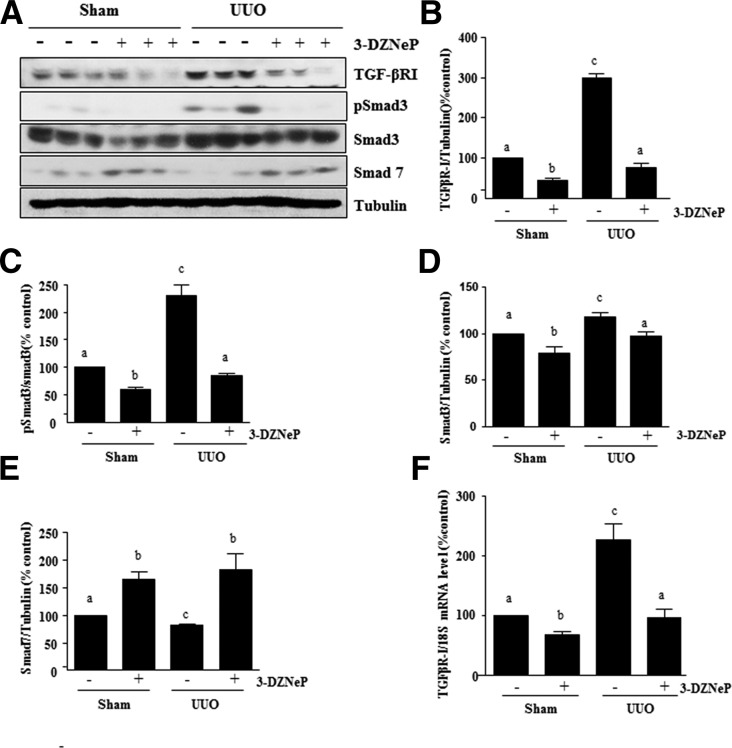

3-DZNeP Inhibits Activation of TGFβ1 Signaling in the Obstructed Kidney

Activation of TGFβ1 signaling is central to the development of renal fibrosis in various models by activation of the Smad3 signaling pathway. In this pathway, TGFβ1 transduces its fibrotic signal through activation of TGFβ-RI followed by recruitment and phosphorylation of Smad3, whereas Smad7 is a well documented key antagonist of TGFβ signaling.40–42 As such, we examined the effect of EZH2 inhibition on the phosphorylation of Smad3 and expressions of TGFβ-RI and Smad7 in the kidney after ureteral obstruction. As shown in Figure 7, A–D, UUO injury resulted in increased protein expression of TGFβ-RI and Smad3 as well as phosphorylation of Smad3 in the kidney. 3-DZNeP treatment significantly reduced these responses. In contrast, the expression level of Smad7 was decreased in the kidney after UUO injury, and 3-DZNeP treatment restored its expression level to the level seen in the sham-operated kidney (Figure 7, A and E). In addition, we also verified the mRNA expression of TGFβ-RI by real-time PCR and showed that UUO injury resulted in a significant increase in the mRNA levels of TGFβ-RI, whereas 3-DZNeP treatment reduced this response (Figure 7F). Because Smad7 protects against renal fibrosis through regulation of TGFβ1 signaling by negative feedback loops, EZH2 inhibition–elicited preservation of Smad7 may, in part, contribute to the inactivation of TGFβ1 signaling and attenuation of renal fibrogenesis in the kidney subjected to UUO injury and treated with 3-DZNeP.

Figure 7.

3-DZNep treatment inhibits activation of the TGFβ/Smad signaling in obstructed kidneys. (A) Kidney tissue lysates were prepared and subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies to TGFβ-RІ, phospho-Smad3, Smad3, Smad7, or tubulin. Expression levels of all of those proteins were quantified by densitometry, and (B) TGFβ-RІ, (D) Smad3, and (E) Smad7 levels were normalized to tubulin; (C) phospho-Smad3 was normalized to its total protein level. (F) mRNA levels of TGFβ-RІ were measured by real-time PCR. The values are the means±SDs (n=6). Bars with different letters (a–c) are significantly different from one another (P<0.05).

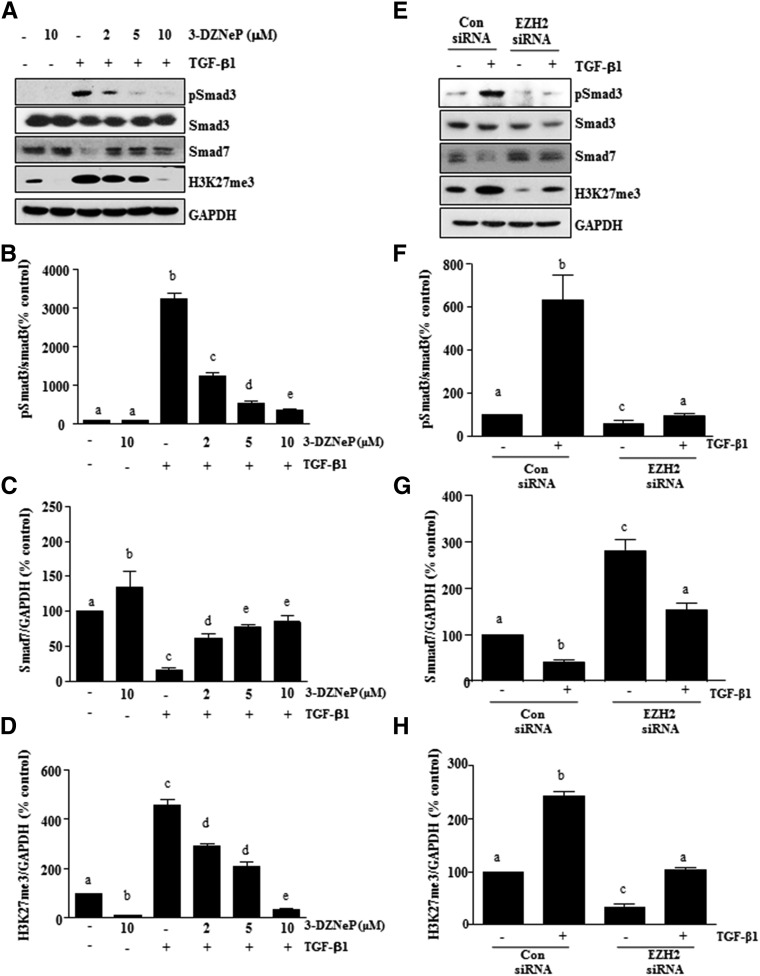

3-DZNeP Reduces the Activation of TGFβ Signaling in Renal Fibroblasts

To specifically show the role of EZH2 in regulation of the TGFβ signaling pathway in renal interstitial fibroblasts, the levels of phospho-Smad3 and total Smad3 were examined in cultured renal fibroblasts stimulated with TGFβ1. As shown in Figure 8A, total Smad3 was expressed in renal interstitial fibroblasts, and TGFβ1 exposure induced its phosphorylation. Treatment with 3-DZNeP decreased the ratio of phospho-Smad3 to Smad3 in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 8, A and B). EZH2 knockdown by siRNA also reduced the level of phospho-Smad3 (Figure 8, E and F). In contrast, depletion of EZH2 with 3-DZNeP or siRNA-antagonized TGFβ1 triggered downregulation of Smad7 expression (Figure 8, A, C, E, and G). As expected, TGFβ1 exposure increased the level of H3K27me3, which was inhibited by either 3-DZNeP treatment or EZH2 downregulation (Figure 8, A, D, E, and H). Thus, these data show that EZH2 plays a critical role in the activation of the TGFβ1 signaling pathway in renal fibroblasts.

Figure 8.

Inhibition of EZH2 suppresses the TGFβ/Smad signaling in renal interstitial fibroblasts. NRK-49F cells were serum starved for 24 hours and then, (A) treated with 3-DZNeP (0–10 μM) for 1 hour or (E) transfected with EZH2 siRNA or scrambled siRNA for 24 hours followed by exposure of cells to TGFβ1 (2 ng/ml) for an additional 24 hours. (A and E) Cell lysates were prepared for immunoblot analysis with antibodies against TGFβ-RІ, phospho-Smad3, Smad3, Smad7, H3K27me3, and GAPDH. (B and F) All of those proteins were quantified by densitometry, and phospho-Smad3 was normalized to its total protein level. The levels of (C and G) Smad7 and (D and H) H3K27me3 were normalized to GAPDH. The values are the means±SDs (n=6). Bars with different letters (a–e) are significantly different from one another (P<0.05).

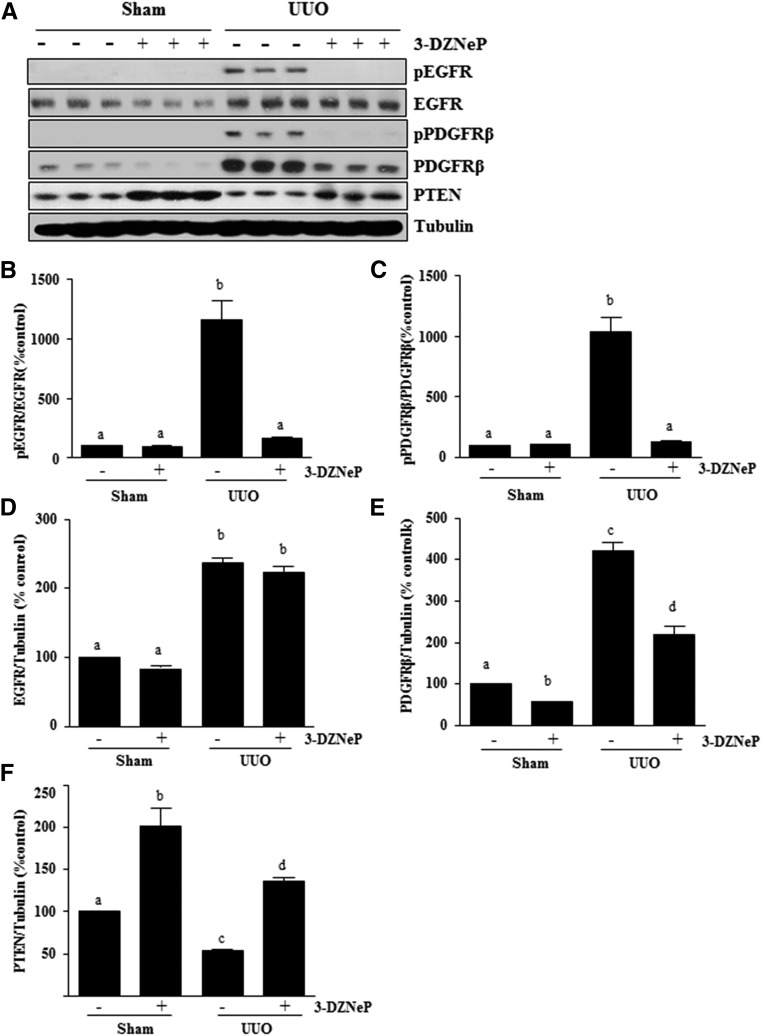

3-DZNeP Inhibits UUO Injury–Induced EGFR and PDGFRβ Phosphorylation and Increases PTEN Expression

EGFR and PDGFRβ are cell surface receptors involved in renal fibroblast activation and proliferation.5,6,43 To determine the effect of 3-DZNeP on EGFR and PDGFRβ activation in the kidney, we examined phosphorylation/expression levels of EGFR and PDGFRβ by immunoblot analysis. The phosphorylated EGFR at Tyr1068 and the phosphorylated PDGFRβ at Tyr751 were barely detectable in the sham-operated kidneys. After UUO injury, their phosphorylation levels were greatly increased in the kidney, whereas administration of 3-DZNeP blocked their phosphorylation (Figure 9, A–C). UUO injury also increased total EGFR and PDGFRβ levels, whereas 3-DZNeP treatment significantly decreased PDGFRβ receptor expression (Figure 9, A, D, and E). However, it should be noted that EGFR phosphorylation was decreased in the injured kidney treated with 3-DZNeP without significant alteration of total EGFR levels (Figure 9, A and D). This suggests that EZH2 plays different regulatory roles on these two tyrosine kinase receptors.

Figure 9.

Blockade of EZH2 inhibits phosphorylation of EGFR and PDGFRβ and upregulation of PTEN in obstructed kidneys. (A) Kidney tissue lysates were prepared and subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies against phospho-EGFR (Tyr1068), phospho-PDGFRβ (Tyr751), EGFR, PDGFRβ, PTEN, or tubulin. All of those proteins were quantified by densitometry, and (B and C) phospho-EGFR and PDGFRβ were normalized to their total protein levels; (D) EGFR, (E) PDGFRβ, and (F) PTEN were normalized to tubulin. Values are the means±SDs (n=6). Bars with different letters (a–d) are significantly different from one another (P<0.05).

A recent report showed that blocking EZH2 with 3-DZNeP increases expression of PTEN, a protein tyrosine phosphatase.44 Because PTEN is associated with the dephosphorylation of multiple tyrosine kinases, including PDGFR and EGFR,45 we examined the effect of EZH2 inhibition on the expression of PTEN in the obstructed kidney. An abundance of PTEN was detected in the sham-operated kidney, but its expression level was significantly downregulated in the UUO-injured kidney. Treatment with 3-DZNeP resulted in a dramatic increase of PTEN expression in the sham-operated kidney and preserved its level in the kidney subjected to UUO injury (Figure 9, A and F). These data suggest that EZH2-mediated silencing of PTEN may contribute to activation of PDGFR and EGFR.

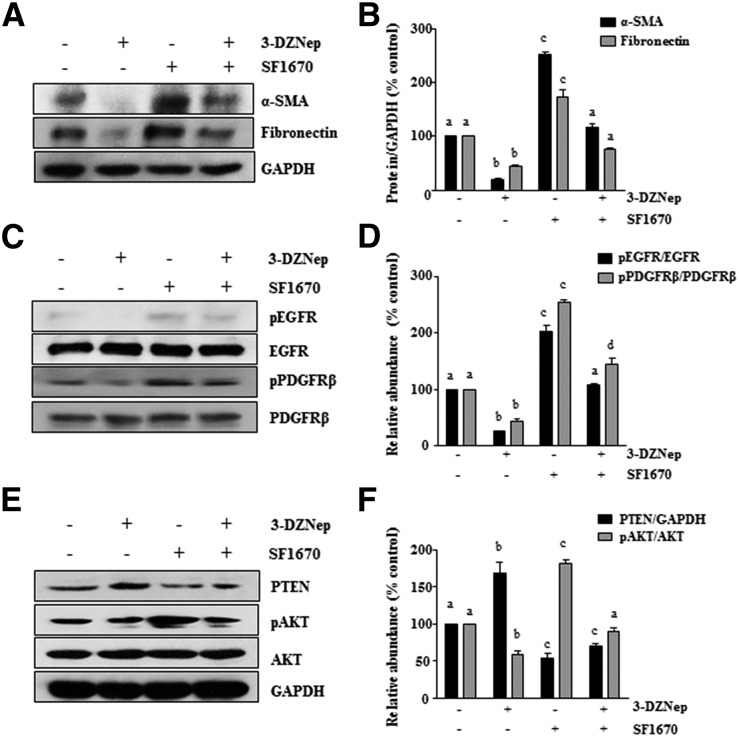

Inhibition of PTEN Reverses the Inhibitory Effect of 3-DZNeP on Phosphorylation of EGFR and PDGFR as well as Activation of Renal Interstitial Fibroblasts In Vitro

To understand how much PTEN induction contributes to the 3-DZNeP–elicited antifibrotic effect, we examined the effect of PTEN inhibition on the activation of renal interstitial fibroblasts by using SF1670, a recently developed specific PTEN inhibitor that binds to the active site of PTEN and increases cellular PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 levels and phosphorylation of Akt46 in vitro. For this purpose, normally cultured NRK-49F cells were pretreated with SF1670 for 1 hour and then, incubated with the vehicle or 3-DZNep for an additional 24 hours. Consistent with our in vivo results shown in Figure 5C, 3-DZNep treatment resulted in decreased expression of α-SMA and fibronectin as well as increased expression of PTEN and the dephosphorylation of EGFR and PDGFR. Interestingly, all of these inhibitory effects of 3-DZNep were largely diminished by pretreatment with SF1670. Notably, incubation with SF1670 alone also slightly increased expression of these proteins, implying that the basal PTEN in normally cultured renal fibroblasts plays a role in limiting their activation to become myofibroblasts. The effectiveness of SF1670 was shown by increased phosphorylation of AKT, one of the downstream targets of PTEN, in cells exposed to this inhibitor alone (Figure 10). Taken together, these data suggest that PTEN plays a critical role in mediating EZH2-regulated activation of diverse profibrotic signaling pathways and subsequent transformation of renal fibroblasts into myofibroblasts.

Figure 10.

Treatment with SF1670, a specific PTEN inhibitor, abolishes the inhibitory effect of 3-DZNep on renal interstitial fibroblast activation in NRK-49F cells. Normally cultured NRK-49F cells were pretreated with 2 μM SF1670 for 1 hour, and then exposed to 10 μM 3-DZNeP for 24 hours. Cell lysates were prepared and subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies against (A) α-SMA and fibronectin; (C) phospho-EGFR, EGFR, phospho-PDGFRβ, and PDGFRβ; (E) PTEN, phospho-AKT, and AKT; or (A and E) GAPDH. (B, D, and F) The levels of α-SMA, fibronectin, phospho-EGFR, EGFR, phospho-PDGFRβ, PDGFRβ, PTEN, phospho-AKT, and AKT were quantified by densitometry and normalized with GAPDH, EGFR, PDGFR, or AKT as indicated. Values are the means±SDs of at least three independent experiments. Bars with different letters (a–d) for each molecule are significantly different from one another (P<0.05).

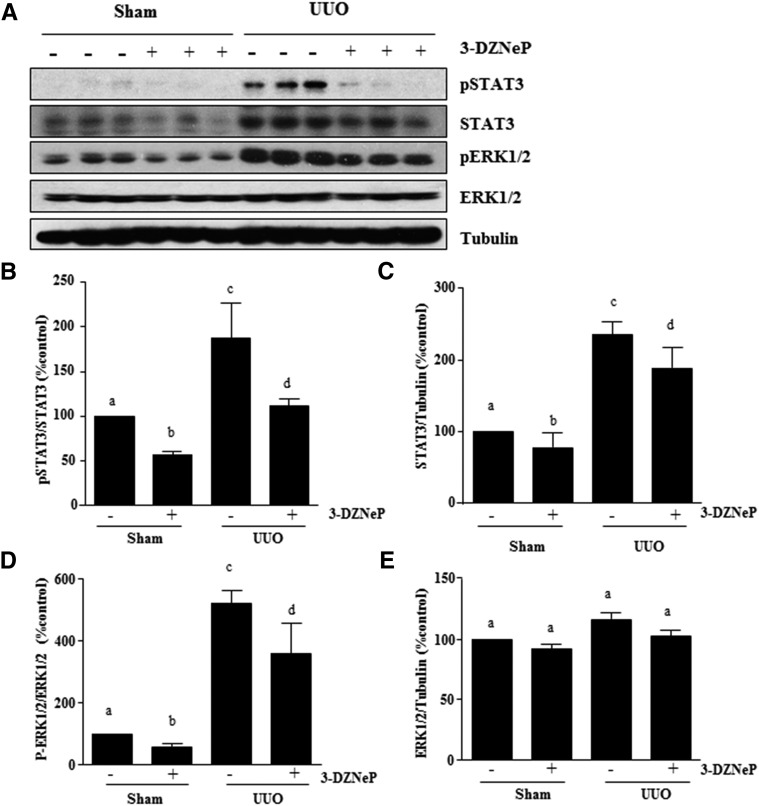

3-DZNeP Inhibits Increased Phosphorylation of STAT3 and ERK1/2 in the Kidney after Obstructed Injury

It has been reported that STAT3 and ERK1/2 signaling pathways are activated in the obstructive kidney and involved in renal interstitial cell proliferation47 and progression of renal fibrosis21 in the murine model of UUO. We, thus, sought to determine whether EZH2 mediates the phosphorylation of these two signaling molecules. As shown in Figure 11, phosphorylation of STAT3 (Tyr705) and ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) was detected in the sham-treated kidney, and their levels were dramatically increased in the kidney after obstructive injury. Inhibition of EZH2 with 3-DZNeP reduced phosphorylation of STAT3 and ERK1/2 in the injured kidney (Figure 11, A, B, and D). Expressions of total STAT3 and ERK1/2 were also increased in mice kidneys after UUO injury compared with normal kidneys. EZH2 inhibition reduced the level of STAT3 but not total ERK1/2 (Figure 11, A, C, and E). Together, our data suggest that EZH2 positively regulates STAT3 signaling by not only promoting its phosphorylation but also, modulating its expression and/or stability.

Figure 11.

3-DZNeP reduces phosphorylation of STAT3 and ERK1/2 in obstructed kidneys. (A) Kidney tissue lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies against phospho-STAT3 (Tyr705), phospho-ERK1/2, STAT3, ERK1/2, or tubulin. Those proteins were quantified by densitometry. (B and D) Phospho-STAT3 and phospho-ERK1/2 levels were normalized with their total protein levels. (C and E) Total STAT3 and ERK1/2 levels were normalized with tubulin. Values are the means±SDs (n=6). Bars with different letters (a–d) are significantly different from one another (P<0.05).

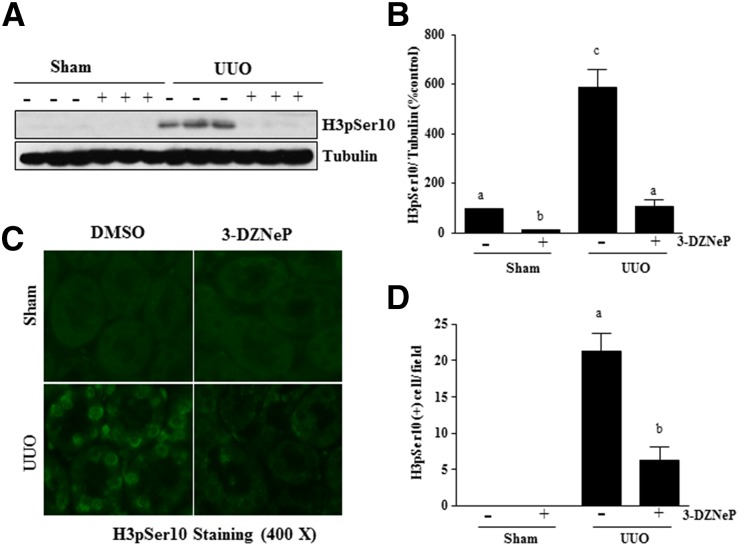

3-DZNeP Inhibits Renal Tubular Cells Arrested at the G2/M of Cell Cycle, Injury, and Apoptosis in the Kidney after Obstructed Injury

Renal epithelial cells arrested at G2/M in the cell cycle resulted in a prominent profibrotic phenotype that produces profibrotic growth factors/cytokines, such as TGFβ1, in the kidney after chronic injury.48 We hypothesized that EZH2 would play an essential role in mediating this process in the injured kidney. To test this hypothesis, we investigated the effect of 3-DZNeP on phosphorylation of histone H3 (p-H3) at serine 10 expression in the obstructed kidney by immunoblot analysis, because p-H3 is a hallmark of cells arrested at the G2/M stage.48 Renal p-H3 was minimally detectable in sham-operated animals but significantly increased after UUO injury. Treatment with 3-DZNeP completely blocked UUO-induced increase of p-H3 in the kidney (Figure 12, A and B). Immunofluorescence staining also showed an increase in the number of renal tubular cells with expression of p-H3 at serine 10 in the kidney after UUO injury, and 3-DZNeP treatment reduced its expression (Figure 12, C and D).

Figure 12.

3-DZNeP inhibits epithelial cells arrested in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle in obstructed kidneys. (A) Kidney tissue lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies against phosphorylation of histone H3 at serine 10 (H3pSer10). (B) H3pSer10 level was quantified by densitometry and normalized with tubulin. (C) Photomicrographs illustrate staining of H3pSer10 in the tissue section of the kidney after treatments as indicated (magnification ×400). (D) The tubular cells with positive staining of H3pSer10 were calculated in ten high-power fields and expressed as means±SDs. Bars with different letters (a–c) are significantly different from one another (P<0.05).

Because development of renal fibrosis is associated with renal tubular cell injury and apoptosis,49 we further examined whether EZH2 mediates these processes. Our results showed that 3-DZNeP treatment also reduced UUO-induced expression of NGAL, a well known marker expressed in renal tubular cells by immunoblot analysis. Additional fluorescence staining showed that this compound reduced the number of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated digoxigenin-deoxyuridine nick–end labeling–positive cells in the UUO-injured kidney (Supplemental Figure 5).

Therefore, our data indicate that EZH2 inhibition may attenuate renal fibrosis by reducing the number of renal epithelial cells arrested at G2/M of the cell cycle and subsequently, decrease the production of some profibrotic factors. Furthermore, EZH2 may play a role in regulating renal tubular injury and apoptosis.

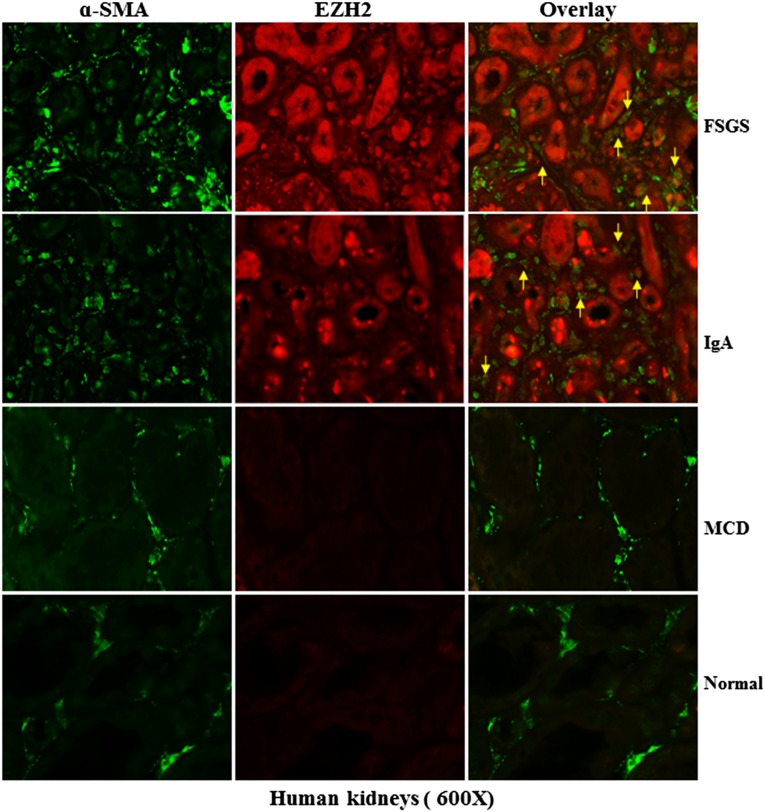

Expression of EZH2 in Human Kidneys with Chronic Disorders

To evaluate the relevance of these findings to human disease, we conducted immunostaining to address whether EZH2 is upregulated in the kidney from subjects with different diseases. As control, normal tissue in dissected kidney from renal cancer was also used. In normal human kidney tissue, very few tubular epithelial cells but not interstitial myofibroblasts (α-SMA positive) stained positive for EZH2. This is consistent with a previous report indicating that nontumorous kidney tissue was mainly negative for EZH2 expression and that only sporadic tubular epithelial cells, if present in the tissue sample, stained positive for EZH2.27 Interestingly, we observed an intense EZH2 labeling in both the cytosol and the nucleus of tubular cells but only in the cytosol of interstitial myofibroblasts in the kidney from patients diagnosed with FSGS. A similar pattern of EZH2 was also observed in kidney samples with IgA nephropathy (Figure 13). Notably, EZH2 was expressed in a portion of but not all myofibroblasts. As in the normal renal tissue, there was little epithelial expression of EZH2 in tubules and no expression in renal interstitial fibroblasts from subjects diagnosed with minimal change disease. Thus, in line with what we had observed in the murine kidney after UUO injury, EZH2 expression is increased in the diseased kidney associated with renal fibrosis in humans. Furthermore, EZH2 is expressed in both renal tubular cells and interstitial fibroblasts under those disease conditions.

Figure 13.

EZH2 is induced specifically in renal tubular cells and interstitial fibroblasts in human CKD. Representative images of double immunofluorescence staining for EZH2 and α-SMA in sections of kidney biopsies from three random subjects diagnosed with FSGS, IgA nephropathy, or minimal change disease (MCD). Nontumor kidney tissue from patients who had renal cell carcinoma and underwent nephropathy was used as a normal control. Arrows indicate EZH2-positive myofibroblasts.

Discussion

Numerous studies have implicated EZH2 as an important mediator of tumor genesis, and its overexpression is associated with poorer patient outcomes in various cancers, including kidney cancer.26 EZH2 activation has also been associated with chronic fibrotic disorders in different organs. For example, EZH2 levels are elevated in the fibrotic liver, and genetic or pharmacologic disruption of this molecule can attenuate liver fibrogenesis by inhibiting fibrotic characteristics of myofibroblasts.50 EZH2–mediated histone hypermethylation is also found to be involved in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.51 However, its role in the activation of renal fibroblasts and development of renal interstitial fibrosis has not yet been explored. Here, we have shown that pharmacologic inhibition and siRNA-mediated downregulation of EZH2 inhibit the activation of cultured renal interstitial fibroblasts. Blockage of EZH2 with 3-DZNeP also attenuates progression of renal fibrosis by reducing deposition of ECM components in a murine model of renal fibrosis induced by UUO. Furthermore, EZH2 inhibition suppressed expression/phosphorylation of multiple membrane receptors and signaling molecules associated with renal fibrogenesis. Thus, we have identified EZH2 as an important epigenetic regulator of renal fibrosis and suggested that it could be a new target for therapeutic interference in CKD.

EZH2 is ubiquitously expressed during early embryogenesis and becomes restricted to the central and peripheral nervous systems and sites of fetal hematopoiesis during later development.52 Although EZH2 is abundantly expressed in the developing kidney, its expression level is quickly decreased after birth. By 3 months of age, only a low level of EZH2 is detectable in the mouse kidney.53 Along with this observation, we detected only a small amount of EZH2 in the sham-operated kidney of mice ages 6–8 weeks old. Interestingly, a dramatic increase in the expression of EZH2 was found in the injured kidney of mice after UUO in both renal tubular cells and interstitial fibroblasts. Similarly, EZH2 is abundantly expressed in the cultured renal interstitial fibroblasts. In line with these observations, we found that EZH2 was induced in human renal tissue from kidney biopsies of patients with CKD caused by varied causes, suggesting that there is clinical relevance of EZH2 induction in the development and progression of human kidney disease. Given that the functional consequence of increased EZH2 is correlated with metastasis and increased aggressiveness of most cancers,54 a high level of EZH2 expression in the injured kidney and renal interstitial fibroblasts may be associated with the pathogenesis of renal fibrosis. Indeed, blocking EZH2 with 3-DZNep suppresses renal myofibroblast activation and development of renal fibrosis. 3-DZNep was also effectively suppressed renal tubular cells arresting at G2/M phase, a profibrotic phenotype that produces profibrotic factors, such as TGFβ1 and connective tissue growth factor, during fibrosis.48 Furthermore, EZH2 inhibition attenuated expression of NGAL and reduced apoptotic renal tubular cells in the UUO-injured kidney, suggesting that EZH2 degradation–elicited renal protection is also associated with reduction of transformation of renal tubular cells from a differentiated phenotype to a less differentiated/profibrotic phenotype as well as alleviation of tubular injury and apoptosis.

Our data indicate that EZH2 inhibition–elicited inactivation of renal myofibroblasts and suppression of renal fibrosis are associated with blockage of TGFβ signaling. TGFβ1 is known to be the critical player in renal fibrogenesis, and it exerts its biologic functions through interaction with TGFβ-R. TGFβ-R is composed of types 1 (TGFβ-RI) and 2 (TGFβ-RII) receptors.39,55 The activated TGFβ-RI recruits Smad3 and then, induces its phosphorylation and translocation to nuclei. In the nucleus, Smad3 drives expression of TGFβ target genes, such as collagens.39,55 In contrast, Smad7 blocks TGFβ1 signaling by inhibiting Smad2/Smad3 phosphorylation and enhancing the degradation of TGFβ-RI.56,57 In this study, we observed that injury to the kidney increased expression of TGFβ-RI and phosphorylation of Smad3 and decreased expression of Smad7, whereas treatment with the EZH2 inhibitor preserved Smad7 expression, which is accompanied by reduced Smad3 phosphorylation and TGFβ-RI expression. These data strongly suggest that maintaining Smad7 stability is a critical mechanism by which EZH2 inhibition suppresses TGFβ/Smad3 signaling. Although there is the possibility that TGFβ-RI expression may also be subject to the epigenetic regulation, it seems less likely that EZH2-mediated H3K27me3 directly binds to TGFβ-RI and promotes its expression, because H3K27me3 forms a repressive chromatin structure, leading to suppression rather than increment of gene expression.26,27 In support of this statement, our Chip assay showed that H3K27m3 is unable to bind to the promoter of TGFβ-RI (data not shown). Nevertheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that EZH2 may also regulate the gene expression through a histone methyltransferase–independent mechanism or silencing of an antifibrotic gene(s). In this regard, it was reported that depletion of EZH2 with siRNA or 3-DZNep increases mRNA levels of PPARγ,58 a negative regulator of myofibroblast activation,59,60 in hepatic stellate cells. Because activation of PPARγ is able to suppress TGFβ signaling events, such as TGFβ1 gene expression and Smad3 phosphorylation, in the fibrotic kidney,61,62 it will be interesting to further investigate whether PPARγ is involved in mediating EZH2 inhibition–elicited inactivation of the TGFβ signaling in the kidney after chronic injury.

Our data also show that EZH2 inhibition resulted in dephosphorylation of EGFR and PDGFR. Because these two growth factor receptors are critically involved in renal fibrogenesis,21,43,63 and inhibition of these two receptors may account, at least in part, for the antifibrotic effect of 3-DZNeP observed in UUO–induced renal fibrosis. Currently, it remains unclear how EZH2 is coupled to these two receptors and regulates their phosphorylation and activation. One possibility is that EZH2 regulates their phosphorylation through modulation of cytosolic tyrosine phosphatase(s) associated with inactivation of those receptors. In support of this notion, Benoit et al.44 have recently reported that blocking EZH2 with 3-DZNeP leads to increased expression of PTEN, a protein tyrosine phosphatase44 that dephosphorylates many tyrosine kinases, including PDGFR and EGFR.45 As we observed, fibrotic injury to the kidney results in downregulation of PTEN, administration of 3-DZNeP restores its expression to the basal level, and PTEN blockage largely reversed the inhibitory effect of 3-DZNeP on EGFR phosphorylation and renal fibroblast activation in cultured renal fibroblasts. This suggests that EZH2-mediated downregulation of PTEN plays a critical role in aberrant activation of renal PDGFR and EGFR after UUO injury.

The interaction of cytokines/growth factors with their receptors initiates different cytosolic signaling pathways that regulate various genes related to the activation of renal fibroblasts and expression of inflammation-associated proteins.64 Our study indicates that EZH2 activity is required for phosphorylation/activation of STAT3 and ERK1/2. This was shown by our in vitro and in vivo studies by using a pharmacologic inhibitor or silencing EZH2 with siRNA. The reduction of STAT3 and ERK1/2 phosphorylation on EZH2 inhibition might also be secondary to its suppression on their upstream receptor tyrosine kinases, such as EGFR. However, recent studies have shown that EZH2 can also bind to and methylate STAT3, leading to enhanced STAT3 activity by increasing tyrosine phosphorylation in stem–like GBM cells.65 This suggests that EZH2 can also regulate STAT3 activation through inducing its methylation directly. Although it remains unclear how STAT3 methylation enhances its phosphorylation, there is the possibility that methylation may protect STAT3 from dephosphorylation. This notion was supported by an observation that STAT3 acetylation can prevent its dephosphorylation.66

Significant research efforts have been aimed at determining the role of EZH2 in a variety of diseases, and therapeutic agents targeted at EZH2 have also been developed. 3-DZNeP has been widely used in vitro and in preclinical studies to investigate the function of EZH2 in cancer and been shown to effectively inhibit cell proliferation, tumor growth, and aggressiveness of various cancers.67–70 Other EZH2 inhibitors, such as GSK126, EI-1, EPZ005687, and EPZ-6438, have also been reported to suppress proliferation of cancer cells, such as lymphomas cells,38,71–73 and GSK126 has been shown to inhibit the growth of EZH2 mutant DLBCL xenografts in mice.38 Currently, EPZ-6438 is under clinical trial to treat patients with B cell lymphoma and advanced solid tumors. Although 3-DZNeP is a potential epigenetic drug, it has been long in the preclinical phase because of the lack of information about its pharmacokinetic properties. A recent detailed pharmacokinetic study in rats showed that intravenous administration of 3-DZNeP to rats at a dose of ≤10 mg/kg body wt did not cause any obvious signs of toxicity, and the kidney was the major organ for its clearance.74 Additionally, a stimulated human whole–body, physiologically based pharmacokinetic model identified that the intravenous administration of 3-DZNeP could be developed for human cancer therapy.74 Because it is predominantly cleared by the kidney, 3-DZNeP at 2 mg/kg was selected for assessing its therapeutic effect on renal fibrosis in our UUO model. With this low-dose regiment, 3-DZNeP showed a strong inhibitory effect on renal myofibroblast activation and renal fibrogenesis, suggesting the perspective for development of it as an antifibrosis drug. As such, additional experiments in other models of renal fibrosis will be required to further determine the efficacy, metabolism, and toxicity of 3-DZNeP before moving it to clinical trials for treating renal fibrosis and other CKDs.

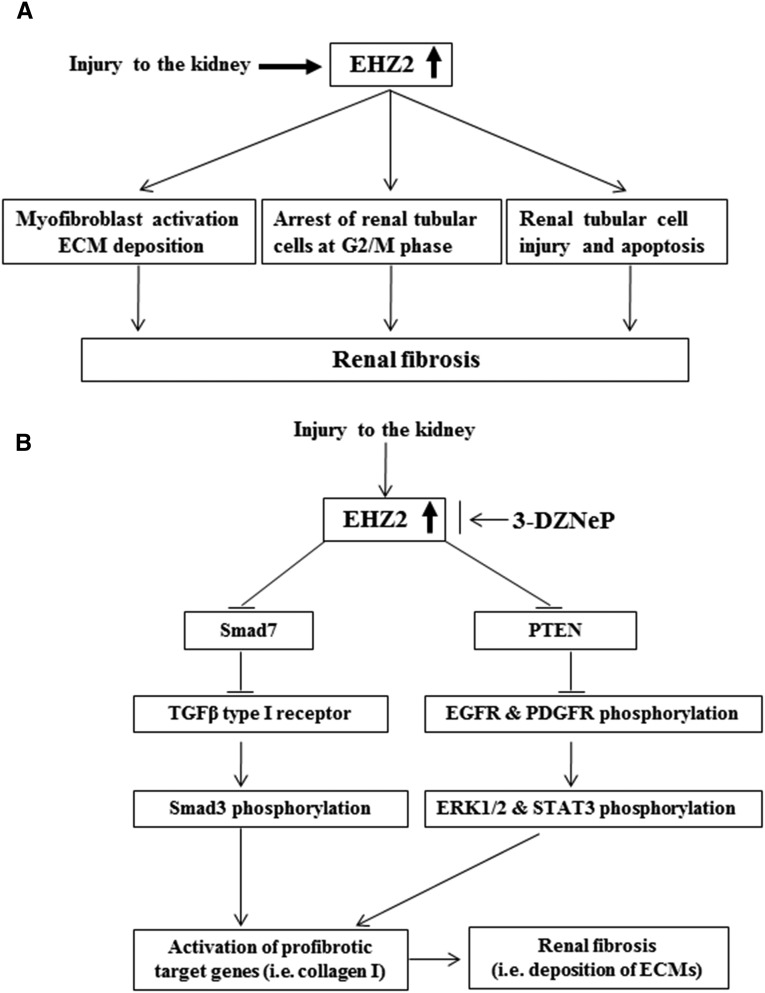

In summary, this is the first study to show that EZH2 is a pivotal regulator of renal fibrogenesis. The downregulation of EZH2 by inhibitors or siRNA reduces the activation of renal interstitial fibroblasts in vitro, and treatment with an EZH2 inhibitor, 3-DZNeP, also attenuates UUO-induced fibrosis in an animal model. The antifibrotic actions of EZH2 blockade are associated with inhibition of expression and/or activation of multiple profibrotic receptors and intracellular signaling pathways (Figure 14). Given that progression of renal fibrosis is a process associated with the interaction of a variety of cellular and molecular mediators,2,3 inhibition of activation and expression of multiple signaling pathways involved in fibrogenesis by targeting EZH2 would have therapeutic potential for treatment of CKD.

Figure 14.

Mechanisms of EZH2–mediated renal fibrosis. (A) Injury to the kidney results in increased expression of EZH2 in renal interstitial fibroblasts and renal tubular cells and subsequently, leads to activation of renal interstitial fibroblasts and arrest of renal tubular cells at the G2/M phase as well as induction of renal tubular cell injury and apoptosis. (B) Increased EZH2 in the kidney after injury causes downregulation of Smad7, a TGFβ type receptor 1 antagonist, and PTEN, a receptor tyrosine kinase–dependent signaling inhibitor. As a result, the TGFβ/Smad3 signaling and EGFR and PDGFR signaling pathways are activated, leading to upregulation of some profibrotic genes, such as collagen 1, and deposition of ECM proteins, a key event in the pathogenesis of chronic renal fibrosis. Blocking EZH2 with 3-DZNeP inhibits activation of these profibrotic signaling pathways and subsequent renal fibrosis through increasing expression of Smad7 and PTEN.

Concise Methods

Chemicals and Antibodies

Antibodies to fibronectin, collagen I (A2), EGFR, TGFβ-RI, Smad7, and GAPDH were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). αVβ6, phospho-Smad3, and Smad3 antibodies were purchased from Abcam, Inc. (Cambridge, MA). NOTCH3 antibody and human TGFβ1 were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). GSK126 and 3-DZNeP were purchased from Active Biochem (Maplewood, NJ) and Selleckchem (Houston, TX), respectively. α-SMA, α-tubulin, and all other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). siRNA specific for rat EZH2 was obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). All other antibodies used in this study were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA).

Cell Culture and Treatment

Rat renal interstitial fibroblasts (NRK-49F) were cultured in DMEM with F12 containing 5% FBS and 0.5% penicillin and streptomycin in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air at 37°C. To determine the effect of 3-DZNeP and GSK126 on fibroblast activation, different doses of were directly added to the subconfluent NRK-49F cells, and then, they were incubated for the indicated time as described in the figures. To determine the effect of EZH2 inhibition on TGFβ1–induced renal fibroblast activation, NRK-49F cells were starved for 24 hours with DMEM containing 0.5% FBS and then, exposed to TGFβ1 for the indicated time in the presence or absence of EZH2 inhibitors.

Transfection of siRNA into Cells

The siRNA oligonucleotides targeted specifically to rat EZH2 were used to downregulate EZH2. In a six-well plate, NRK-49F cells were seeded to 50%–60% confluence in antibiotic-free medium and grown for 24 hours. Then, cells in each well were transfected with siRNA (100 pmol) specific for EZH2 using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In parallel, scrambled siRNA (100 pmol) was used as a control for off-target changes in NRK-49F; 24 hours after transfection, the medium was changed, and cells were incubated for an additional 24 hours before being harvested for analysis.

Animals and Experimental Design

The UUO model was established in male C57 black mice that weighed 20–25 g (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) as described in our previous studies.21,64 In brief, the abdominal cavity was exposed by a midline incision, and the left ureter was isolated and ligated. The contralateral kidney was used as a control. To examine the role of EZH2 in renal fibrosis, 3-DZNeP (2 mg/kg) in 50 μl DMSO was immediately administered intraperitoneally after ureteral ligation and then, given daily for 6 days. The dose of 3-DZNeP was selected according to a previous report.75 For the UUO alone group, mice were injected with an equivalent amount of DMSO. The animals were euthanized, and the kidneys were collected at day 7 after UUO for protein analysis and histologic examination. All experimental procedures were performed according to the US Guidelines on the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Lifespan Animal Welfare Committee.

Immunoblot Analyses

To prepare protein samples for Western blotting, the kidney tissue samples were homogenized with cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology) and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). After various treatments, cells were washed once with ice-cold PBS and harvested in a cell lysis buffer mixed with a protease inhibitor cocktail. Proteins (25 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. After incubation with 5% nonfat milk for 1 hour at room temperature, membranes were incubated with a primary antibody overnight at 4°C and then, appropriate horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature. Bound antibodies were visualized by chemiluminescence detection.

Quantitative Real–Time RT-PCR

The mRNA expression of TGFβ-RI was measured using quantitative real–time PCR analysis. The primers and detailed methods are described in Supplemental Figures 1–5.

Histochemical and Immunofluorescence Staining

Immunofluorescence staining was carried out according to the procedure described in our previous studies.21 Masson trichrome staining was performed according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer (Sigma-Aldrich). For assessment of renal fibrosis quantitatively, the collagen tissue area was measured using Image Pro-Plus Software (Media-Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD) by drawing a line around the perimeter of the positive staining area, and the average ratio to each microscopic field (magnification ×200) was calculated and graphed. For immunofluorescence staining, rabbit anti–p-H3 at serine 10 (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA), rabbit anti-EZH2 (Cell Signaling Technology), and mouse anti–α-SMA (Sigma-Aldrich) antibodies were used. Renal tubular cell apoptosis was analyzed by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated digoxigenin-deoxyuridine nick–end labeling on the basis of the protocol provided by the manufacturer (Roche Diagnostics).

Densitometry Analyses

The semiquantitative analysis of different proteins was carried out using ImageJ software developed at the National Institutes of Health. The quantification is on the basis of the intensity (density) of the band, which is calculated by the area and pixel value of the band. The quantification data are given as a ratio between target protein and loading control (housekeeping protein).

Statistical Analyses

Data are presented as means±SDs and were subjected to one-way ANOVA. Multiple means were compared using Tukey test, and differences between two groups were determined by t test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by US National Institutes of Health Grant 5R01DK085065 (to S.Z.), National Nature Science Foundation of China Grants 81270778 (to S.Z.) and 81470920 (to S.Z.), and Key Discipline Construction Project of Pudong Health Bureau of Shanghai PWZx2014-06 (to S.Z.).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2015040457/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Liu Y: Epithelial to mesenchymal transition in renal fibrogenesis: Pathologic significance, molecular mechanism, and therapeutic intervention. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 1–12, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neilson EG: Mechanisms of disease: Fibroblasts--a new look at an old problem. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol 2: 101–108, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wynn TA: Cellular and molecular mechanisms of fibrosis. J Pathol 214: 199–210, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meran S, Steadman R: Fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in renal fibrosis. Int J Exp Pathol 92: 158–167, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonner JC: Regulation of PDGF and its receptors in fibrotic diseases. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 15: 255–273, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Terzi F, Burtin M, Hekmati M, Federici P, Grimber G, Briand P, Friedlander G: Targeted expression of a dominant-negative EGF-R in the kidney reduces tubulo-interstitial lesions after renal injury. J Clin Invest 106: 225–234, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lautrette A, Li S, Alili R, Sunnarborg SW, Burtin M, Lee DC, Friedlander G, Terzi F: Angiotensin II and EGF receptor cross-talk in chronic kidney diseases: A new therapeutic approach. Nat Med 11: 867–874, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang W, Koka V, Lan HY: Transforming growth factor-beta and Smad signalling in kidney diseases. Nephrology (Carlton) 10: 48–56, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qin H, Wang L, Feng T, Elson CO, Niyongere SA, Lee SJ, Reynolds SL, Weaver CT, Roarty K, Serra R, Benveniste EN, Cong Y: TGF-beta promotes Th17 cell development through inhibition of SOCS3. J Immunol 183: 97–105, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song CY, Kim BC, Hong HK, Lee HS: TGF-beta type II receptor deficiency prevents renal injury via decrease in ERK activity in crescentic glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int 71: 882–888, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki K, Wilkes MC, Garamszegi N, Edens M, Leof EB: Transforming growth factor beta signaling via Ras in mesenchymal cells requires p21-activated kinase 2 for extracellular signal-regulated kinase-dependent transcriptional responses. Cancer Res 67: 3673–3682, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vignais ML, Sadowski HB, Watling D, Rogers NC, Gilman M: Platelet-derived growth factor induces phosphorylation of multiple JAK family kinases and STAT proteins. Mol Cell Biol 16: 1759–1769, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lo HW, Hsu SC, Xia W, Cao X, Shih JY, Wei Y, Abbruzzese JL, Hortobagyi GN, Hung MC: Epidermal growth factor receptor cooperates with signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 to induce epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer cells via up-regulation of TWIST gene expression. Cancer Res 67: 9066–9076, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trojanowska M: Noncanonical transforming growth factor beta signaling in scleroderma fibrosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 21: 623–629, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tampe B, Zeisberg M: Evidence for the involvement of epigenetics in the progression of renal fibrogenesis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 29[Suppl 1]: i1–i8, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wing MR, Ramezani A, Gill HS, Devaney JM, Raj DS: Epigenetics of progression of chronic kidney disease: Fact or fantasy? Semin Nephrol 33: 363–374, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hassler MR, Egger G: Epigenomics of cancer - emerging new concepts. Biochimie 94: 2219–2230, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ledford H: Epigenetics: Marked for success. Nature 483: 637–639, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maher ER: Genomics and epigenomics of renal cell carcinoma. Semin Cancer Biol 23: 10–17, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sandoval J, Esteller M: Cancer epigenomics: Beyond genomics. Curr Opin Genet Dev 22: 50–55, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pang M, Kothapally J, Mao H, Tolbert E, Ponnusamy M, Chin YE, Zhuang S: Inhibition of histone deacetylase activity attenuates renal fibroblast activation and interstitial fibrosis in obstructive nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F996–F1005, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bechtel W, McGoohan S, Zeisberg EM, Müller GA, Kalbacher H, Salant DJ, Müller CA, Kalluri R, Zeisberg M: Methylation determines fibroblast activation and fibrogenesis in the kidney. Nat Med 16: 544–550, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cao R, Zhang Y: The functions of E(Z)/EZH2-mediated methylation of lysine 27 in histone H3. Curr Opin Genet Dev 14: 155–164, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morey L, Helin K: Polycomb group protein-mediated repression of transcription. Trends Biochem Sci 35: 323–332, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Margueron R, Reinberg D: The Polycomb complex PRC2 and its mark in life. Nature 469: 343–349, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shen H, Laird PW: Interplay between the cancer genome and epigenome. Cell 153: 38–55, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wagener N, Macher-Goeppinger S, Pritsch M, Hüsing J, Hoppe-Seyler K, Schirmacher P, Pfitzenmaier J, Haferkamp A, Hoppe-Seyler F, Hohenfellner M: Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) expression is an independent prognostic factor in renal cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer 10: 524, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Varambally S, Dhanasekaran SM, Zhou M, Barrette TR, Kumar-Sinha C, Sanda MG, Ghosh D, Pienta KJ, Sewalt RG, Otte AP, Rubin MA, Chinnaiyan AM: The polycomb group protein EZH2 is involved in progression of prostate cancer. Nature 419: 624–629, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kleer CG, Cao Q, Varambally S, Shen R, Ota I, Tomlins SA, Ghosh D, Sewalt RG, Otte AP, Hayes DF, Sabel MS, Livant D, Weiss SJ, Rubin MA, Chinnaiyan AM: EZH2 is a marker of aggressive breast cancer and promotes neoplastic transformation of breast epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100: 11606–11611, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu J, Yu J, Rhodes DR, Tomlins SA, Cao X, Chen G, Mehra R, Wang X, Ghosh D, Shah RB, Varambally S, Pienta KJ, Chinnaiyan AM: A polycomb repression signature in metastatic prostate cancer predicts cancer outcome. Cancer Res 67: 10657–10663, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gonzalez ME, Li X, Toy K, DuPrie M, Ventura AC, Banerjee M, Ljungman M, Merajver SD, Kleer CG: Downregulation of EZH2 decreases growth of estrogen receptor-negative invasive breast carcinoma and requires BRCA1. Oncogene 28: 843–853, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu C, Han HD, Mangala LS, Ali-Fehmi R, Newton CS, Ozbun L, Armaiz-Pena GN, Hu W, Stone RL, Munkarah A, Ravoori MK, Shahzad MM, Lee JW, Mora E, Langley RR, Carroll AR, Matsuo K, Spannuth WA, Schmandt R, Jennings NB, Goodman BW, Jaffe RB, Nick AM, Kim HS, Guven EO, Chen YH, Li LY, Hsu MC, Coleman RL, Calin GA, Denkbas EB, Lim JY, Lee JS, Kundra V, Birrer MJ, Hung MC, Lopez-Berestein G, Sood AK: Regulation of tumor angiogenesis by EZH2. Cancer Cell 18: 185–197, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tan J, Yang X, Zhuang L, Jiang X, Chen W, Lee PL, Karuturi RK, Tan PB, Liu ET, Yu Q: Pharmacologic disruption of Polycomb-repressive complex 2-mediated gene repression selectively induces apoptosis in cancer cells. Genes Dev 21: 1050–1063, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hibino S, Saito Y, Muramatsu T, Otani A, Kasai Y, Kimura M, Saito H: Inhibitors of enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) activate tumor-suppressor microRNAs in human cancer cells. Oncogenesis 3: e104, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mack M, Yanagita M: Origin of myofibroblasts and cellular events triggering fibrosis. Kidney Int 87: 297–307, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duffield JS: Cellular and molecular mechanisms in kidney fibrosis. J Clin Invest 124: 2299–2306, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Loeffler I, Wolf G: Transforming growth factor-β and the progression of renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 29[Suppl 1]: i37–i45, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCabe MT, Ott HM, Ganji G, Korenchuk S, Thompson C, Van Aller GS, Liu Y, Graves AP, Della Pietra A 3rd, Diaz E, LaFrance LV, Mellinger M, Duquenne C, Tian X, Kruger RG, McHugh CF, Brandt M, Miller WH, Dhanak D, Verma SK, Tummino PJ, Creasy CL: EZH2 inhibition as a therapeutic strategy for lymphoma with EZH2-activating mutations. Nature 492: 108–112, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu Y: Renal fibrosis: New insights into the pathogenesis and therapeutics. Kidney Int 69: 213–217, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schnaper HW, Jandeska S, Runyan CE, Hubchak SC, Basu RK, Curley JF, Smith RD, Hayashida T: TGF-beta signal transduction in chronic kidney disease. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 14: 2448–2465, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abbate M, Zoja C, Rottoli D, Corna D, Tomasoni S, Remuzzi G: Proximal tubular cells promote fibrogenesis by TGF-beta1-mediated induction of peritubular myofibroblasts. Kidney Int 61: 2066–2077, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coimbra TM, Carvalho J, Fattori A, Da Silva CG, Lachat JJ: Transforming growth factor-beta production during the development of renal fibrosis in rats with subtotal renal ablation. Int J Exp Pathol 77: 167–173, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ludewig D, Kosmehl H, Sommer M, Böhmer FD, Stein G: PDGF receptor kinase blocker AG1295 attenuates interstitial fibrosis in rat kidney after unilateral obstruction. Cell Tissue Res 299: 97–103, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Benoit YD, Witherspoon MS, Laursen KB, Guezguez A, Beauséjour M, Beaulieu JF, Lipkin SM, Gudas LJ: Pharmacological inhibition of polycomb repressive complex-2 activity induces apoptosis in human colon cancer stem cells. Exp Cell Res 319: 1463–1470, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abouantoun TJ, Castellino RC, MacDonald TJ: Sunitinib induces PTEN expression and inhibits PDGFR signaling and migration of medulloblastoma cells. J Neurooncol 101: 215–226, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosivatz E, Matthews JG, McDonald NQ, Mulet X, Ho KK, Lossi N, Schmid AC, Mirabelli M, Pomeranz KM, Erneux C, Lam EW, Vilar R, Woscholski R: A small molecule inhibitor for phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN). ACS Chem Biol 1: 780–790, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Han Y, Masaki T, Hurst LA, Ikezumi Y, Trzaskos JM, Atkins RC, Nikolic-Paterson DJ: Extracellular signal-regulated kinase-dependent interstitial macrophage proliferation in the obstructed mouse kidney. Nephrology (Carlton) 13: 411–418, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang L, Besschetnova TY, Brooks CR, Shah JV, Bonventre JV: Epithelial cell cycle arrest in G2/M mediates kidney fibrosis after injury. Nat Med 16: 535–543, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bonventre JV: Primary proximal tubule injury leads to epithelial cell cycle arrest, fibrosis, vascular rarefaction, and glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 4: 39–44, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Atta H, El-Rehany M, Hammam O, Abdel-Ghany H, Ramzy M, Roderfeld M, Roeb E, Al-Hendy A, Raheim SA, Allam H, Marey H: Mutant MMP-9 and HGF gene transfer enhance resolution of CCl4-induced liver fibrosis in rats: Role of ASH1 and EZH2 methyltransferases repression. PLoS One 9: e112384, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Coward WR, Feghali-Bostwick CA, Jenkins G, Knox AJ, Pang L: A central role for G9a and EZH2 in the epigenetic silencing of cyclooxygenase-2 in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. FASEB J 28: 3183–3196, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hobert O, Sures I, Ciossek T, Fuchs M, Ullrich A: Isolation and developmental expression analysis of Enx-1, a novel mouse Polycomb group gene. Mech Dev 55: 171–184, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Margueron R, Li G, Sarma K, Blais A, Zavadil J, Woodcock CL, Dynlacht BD, Reinberg D: Ezh1 and Ezh2 maintain repressive chromatin through different mechanisms. Mol Cell 32: 503–518, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Deb G, Singh AK, Gupta S: EZH2: Not EZHY (easy) to deal. Mol Cancer Res 12: 639–653, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Böttinger EP: TGF-beta in renal injury and disease. Semin Nephrol 27: 309–320, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lan HY, Chung AC: TGF-β/Smad signaling in kidney disease. Semin Nephrol 32: 236–243, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tian Y, Liao F, Wu G, Chang D, Yang Y, Dong X, Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Wu G: Ubiquitination and regulation of Smad7 in the TGF-β1/Smad signaling of aristolochic acid nephropathy. Toxicol Mech Methods 25: 645–652, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mann J, Chu DC, Maxwell A, Oakley F, Zhu NL, Tsukamoto H, Mann DA: MeCP2 controls an epigenetic pathway that promotes myofibroblast transdifferentiation and fibrosis. Gastroenterology 138: 705–714, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hazra S, Xiong S, Wang J, Rippe RA, Krishna V, Chatterjee K, Tsukamoto H: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma induces a phenotypic switch from activated to quiescent hepatic stellate cells. J Biol Chem 279: 11392–11401, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miyahara T, Schrum L, Rippe R, Xiong S, Yee HF Jr., Motomura K, Anania FA, Willson TM, Tsukamoto H: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and hepatic stellate cell activation. J Biol Chem 275: 35715–35722, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kawai T, Masaki T, Doi S, Arakawa T, Yokoyama Y, Doi T, Kohno N, Yorioka N: PPAR-gamma agonist attenuates renal interstitial fibrosis and inflammation through reduction of TGF-beta. Lab Invest 89: 47–58, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang W, Liu F, Chen N: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPAR-gamma) agonists attenuate the profibrotic response induced by TGF-beta1 in renal interstitial fibroblasts. Mediators Inflamm 2007: 62641, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu N, Tolbert E, Pang M, Ponnusamy M, Yan H, Zhuang S: Suramin inhibits renal fibrosis in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 1064–1075, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pang M, Ma L, Gong R, Tolbert E, Mao H, Ponnusamy M, Chin YE, Yan H, Dworkin LD, Zhuang S: A novel STAT3 inhibitor, S3I-201, attenuates renal interstitial fibroblast activation and interstitial fibrosis in obstructive nephropathy. Kidney Int 78: 257–268, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kim E, Kim M, Woo DH, Shin Y, Shin J, Chang N, Oh YT, Kim H, Rheey J, Nakano I, Lee C, Joo KM, Rich JN, Nam DH, Lee J: Phosphorylation of EZH2 activates STAT3 signaling via STAT3 methylation and promotes tumorigenicity of glioblastoma stem-like cells. Cancer Cell 23: 839–852, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Krämer OH, Heinzel T: Phosphorylation-acetylation switch in the regulation of STAT1 signaling. Mol Cell Endocrinol 315: 40–48, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Alimova I, Venkataraman S, Harris P, Marquez VE, Northcott PA, Dubuc A, Taylor MD, Foreman NK, Vibhakar R: Targeting the enhancer of zeste homologue 2 in medulloblastoma. Int J Cancer 131: 1800–1809, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kemp CD, Rao M, Xi S, Inchauste S, Mani H, Fetsch P, Filie A, Zhang M, Hong JA, Walker RL, Zhu YJ, Ripley RT, Mathur A, Liu F, Yang M, Meltzer PA, Marquez VE, De Rienzo A, Bueno R, Schrump DS: Polycomb repressor complex-2 is a novel target for mesothelioma therapy. Clin Cancer Res 18: 77–90, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kalushkova A, Fryknäs M, Lemaire M, Fristedt C, Agarwal P, Eriksson M, Deleu S, Atadja P, Osterborg A, Nilsson K, Vanderkerken K, Oberg F, Jernberg-Wiklund H: Polycomb target genes are silenced in multiple myeloma. PLoS One 5: e11483, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gannon OM, Merida de Long L, Endo-Munoz L, Hazar-Rethinam M, Saunders NA: Dysregulation of the repressive H3K27 trimethylation mark in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma contributes to dysregulated squamous differentiation. Clin Cancer Res 19: 428–441, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Qi W, Chan H, Teng L, Li L, Chuai S, Zhang R, Zeng J, Li M, Fan H, Lin Y, Gu J, Ardayfio O, Zhang JH, Yan X, Fang J, Mi Y, Zhang M, Zhou T, Feng G, Chen Z, Li G, Yang T, Zhao K, Liu X, Yu Z, Lu CX, Atadja P, Li E: Selective inhibition of Ezh2 by a small molecule inhibitor blocks tumor cells proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109: 21360–21365, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Knutson SK, Wigle TJ, Warholic NM, Sneeringer CJ, Allain CJ, Klaus CR, Sacks JD, Raimondi A, Majer CR, Song J, Scott MP, Jin L, Smith JJ, Olhava EJ, Chesworth R, Moyer MP, Richon VM, Copeland RA, Keilhack H, Pollock RM, Kuntz KW: A selective inhibitor of EZH2 blocks H3K27 methylation and kills mutant lymphoma cells. Nat Chem Biol 8: 890–896, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Knutson SK, Kawano S, Minoshima Y, Warholic NM, Huang KC, Xiao Y, Kadowaki T, Uesugi M, Kuznetsov G, Kumar N, Wigle TJ, Klaus CR, Allain CJ, Raimondi A, Waters NJ, Smith JJ, Porter-Scott M, Chesworth R, Moyer MP, Copeland RA, Richon VM, Uenaka T, Pollock RM, Kuntz KW, Yokoi A, Keilhack H: Selective inhibition of EZH2 by EPZ-6438 leads to potent antitumor activity in EZH2-mutant non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Mol Cancer Ther 13: 842–854, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sun F, Lee L, Zhang Z, Wang X, Yu Q, Duan X, Chan E: Preclinical pharmacokinetic studies of 3-deazaneplanocin A, a potent epigenetic anticancer agent, and its human pharmacokinetic prediction using GastroPlus™. Eur J Pharm Sci 77: 290–302, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Krämer M, Dees C, Huang J, Schlottmann I, Palumbo-Zerr K, Zerr P, Gelse K, Beyer C, Distler A, Marquez VE, Distler O, Schett G, Distler JH: Inhibition of H3K27 histone trimethylation activates fibroblasts and induces fibrosis. Ann Rheum Dis 72: 614–620, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.