Abstract

The NFκB transcription factor family facilitates the activation of dendritic cells (DCs) and CD4+ T helper (Th) cells, which are important for protective adaptive immunity. Inappropriate activation of these immune cells may cause inflammatory disease, and NFκB inhibitors are promising anti–inflammatory drug candidates. Here, we investigated whether inhibiting the NFκB–inducing kinase IKK2 can attenuate crescentic GN, a severe DC– and Th cell–dependent kidney inflammatory disease. Prophylactic pharmacologic IKK2 inhibition reduced DC and Th cell activation and ameliorated nephrotoxic serum–induced GN in mice. However, therapeutic IKK2 inhibition during ongoing disease aggravated the nephritogenic immune response and disease symptoms. This effect resulted from the renal loss of regulatory T cells, which have been shown to protect against crescentic GN and which require IKK2. In conclusion, although IKK2 inhibition can suppress the induction of nephritogenic immune responses in vivo, it may aggravate such responses in clinically relevant situations, because it also impairs regulatory T cells and thereby, unleashes preexisting nephritogenic responses. Our findings argue against using IKK2 inhibitors in chronic GN and perhaps, other immune–mediated diseases.

Keywords: glomerulonephritis, chronic kidney disease, immunology, immunosuppression, lymphocytes, progression of chronic renal failure

Inhibitor of NFκB kinase subunit 2 (IKK2; also known as IKKβ) triggers the classic NFκB activation pathway, which is critical for the activation of dendritic cells (DCs) and CD4+ T helper (Th) cells during adaptive immune responses.1,2 NFκB–dependent DC activation (for example, in response to microbial molecular patterns) results in the upregulation of costimulatory molecules, such as CD80, CD86, or CD40, which promote immunogenic Th cell activation.3 IKK2 deletion in T cells prevented their activation and effector function.1,4 Thus, the NFκB pathway is widely considered to promote inflammation, and various NFκB inhibitors are currently being tested for the treatment of immune-mediated and inflammatory diseases.5 Some IKK2 inhibitors have shown anti-inflammatory effects in preclinical studies on arthritis and pulmonary disease.6,7

By contrast, the targeted genetic deletion of IKK2 in nonimmune cells, such as keratinocytes or hepatocytes, caused inflammatory disease of skin and liver, respectively.8,9 Targeted IKK2 deletion in DCs suppressed not only their activation but also, their migration into draining lymph nodes and their ability to induce differentiation of regulatory T (Treg) cells.10 Such Treg cells are important to maintain immunologic self-tolerance by inhibiting autoreactive T and B cells and require the forkhead/winged–helix box P3 transcription factor.11–13 They also require classic NFκB pathway components, including IKK2, for their development in the thymus.4,14–16 Furthermore, recent studies described distinct NFκB components with anti-inflammatory properties.17,18 Thus, there are both pro- and anti-inflammatory functions of the NFκB pathway, but their interplay and regulation in the in vivo situation are unclear.4,19

NFκB activation has also been observed in patients20 and experimental models of GN.21 Crescentic GN (cGN) is a severe inflammatory kidney disease, which is mediated by Th cells specific for glomerular antigens and may rapidly progress to terminal kidney failure.22,23 It can be mimicked by the passive nephrotoxic nephritis (pNTN) model, which is induced by injecting a nephrotoxic sheep antiserum specific for murine glomerular components into mice. In the immune activation phase of this model, which lasts until days 4–5 after serum injection, DCs in lymphatic organs capture sheep Ig and activate specific Th cells. In the effector phase starting at days 3–4, these Th cells enter the kidney, where the antiserum is deposited because of its specificity, and produce effector cytokines, like IFNγ, that activate macrophages.22,23 During their effector phase, Th cells can be regulated by kidney-resident DCs, whose activation state determines whether they stimulate or inhibit the Th cells and thus, whether nephritis progresses or heals.24

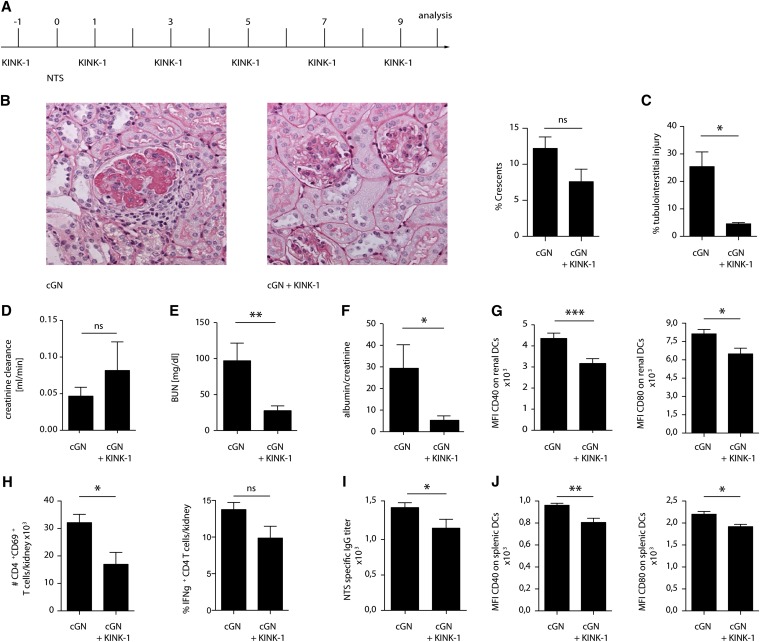

Here, we hypothesized that inhibiting DC and Th cell activation with an NFκB inhibitor should attenuate GN. We tested this hypothesis by treating mice every other day with the IKK2 inhibitor kinase inhibitor of NFκB-1 (KINK-1)7,25 starting 1 day before administration of the nephrotoxic serum (experimental plan is in Figure 1A). This drug reduced NFκB nuclear translocation in vivo (Supplemental Figure 1) and attenuated pNTN, which was evidenced by fewer crescents in histologic sections (Figure 1B), lower tubulointerstitial injury (Figure 1C), higher creatinine clearance (Figure 1D), lower BUN (Figure 1E), and lower proteinuria (Figure 1F). Renal DCs (flow cytometric gating strategy is in Supplemental Figure 2) showed a less activated phenotype (Figure 1G), and intrarenal activated Th cells producing IFNγ were less frequent (Figure 1H). Thus, IKK2 inhibition starting before pNTN induction attenuated the nephritogenic Th cell response and disease symptoms.

Figure 1.

Prophylactic IKK2 inhibition blocks the induction of pNTN. Prophylactic IKK2 inhibition in pNTN. (A) Experimental plan, (B) representative periodic acid–Schiff–stained glomeruli and percentage of crescentic glomeruli, (C) tubulointerstitial injury, (D) creatinine clearance, (E) BUN, (F) albumin-to-creatinine ratio, (G) expression of the DC activation markers CD40 and CD80, (H) numbers of activated and percentages of IFNγ–producing Th cells, (I) IgG titers of anti–sheep Ig antibodies, and (J) DC activation markers on splenic cells in nephritic mice prophylactically treated with KINK-1 or vehicle. Data are representative of three independent experiments (n=5; Kruskal–Wallis test with post hoc analysis by Mann–Whitney test). cGN, crescentic glomerulonephritis; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; NTS, nephrotoxic serum nephritis. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

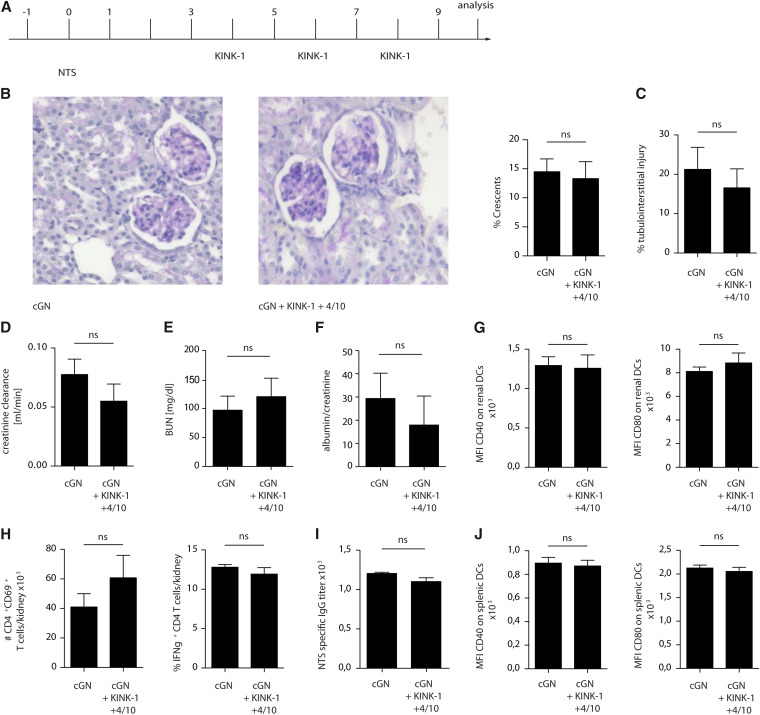

We noted that anti–sheep Ig titers, which can be considered a parameter for the nephritogenic Th cell response, were systemically reduced after IKK2 inhibition (Figure 1I). Furthermore, DCs in the spleen appeared less mature (Figure 1J). This indicated that the induction of the pNTN model had been compromised; in other words, prophylactic IKK2 inhibition before pNTN induction (Figure 1A) had suppressed the induction of this disease model rather than preventing its progression. Because prophylactic IKK2 inhibition does not mimic the clinically relevant situation of a patient presenting with ongoing disease, we modified our protocol and applied the IKK2 inhibitor on days 4, 6, and 8 after disease induction (experimental plan is in Figure 2A). However, under these conditions, pNTN was no longer attenuated (Figure 2, B–F), and neither renal inflammation (Figure 2, G and H) nor systemic antirenal immune response (Figure 2, I and J) were decreased. This might indicate that IKK2 inhibition cannot attenuate ongoing pNTN. Alternatively, the duration of IKK2 inhibition (on days 4, 6, and 8 compared with six times treatment in Figure 1) may have been too short to affect disease.

Figure 2.

Short–term therapeutic IKK2 inhibition fails to attenuate pNTN. (A) Experimental plan, (B) representative periodic acid–Schiff–stained glomeruli and percentage of crescentic glomeruli, (C) tubulointerstitial injury, (D) creatinine clearance, (E) BUN, (F) albumin-to-creatinine ratio, (G) expression of the DC activation markers CD40 and CD80, (H) numbers of activated and percentages of IFNγ–producing Th cells, (I) IgG titers of anti–sheep Ig antibodies, and (J) DC activation markers on splenic cells in nephritic mice treated therapeutically (starting day +4 after the induction of nephrotoxic nephritis) with KINK-1 or vehicle. Data are representative of three independent experiments (n=4; Kruskal–Wallis test with post hoc analysis by Mann–Whitney test). cGN, crescentic glomerulonephritis; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; NTS, nephrotoxic serum nephritis.

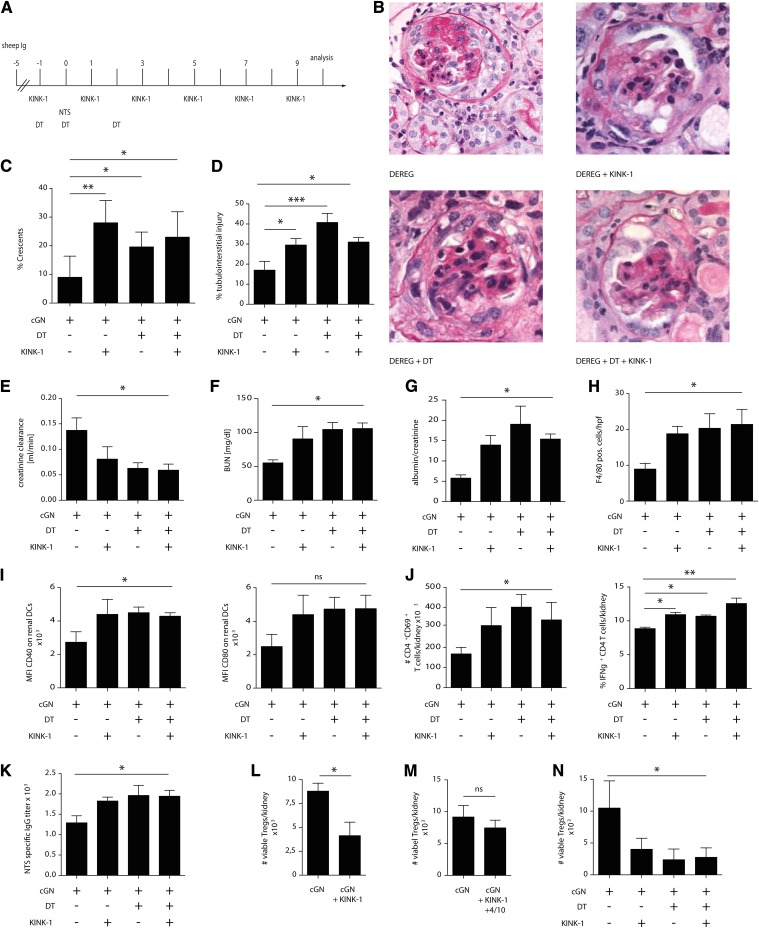

To distinguish between these possibilities, we decided to use a protocol that allows prolonged IKK2 inhibition selectively in the Th cell effector phase. Because these phases overlap between days 3 and 5 in pNTN,23 we switched to the accelerated nephrotoxic nephritis (aNTN) model, where mice are first immunized with sheep Ig to allow for the activation of specific Th cells without a nephritogenic effector phase; 5 days later, we injected a lower dose of nephrotoxic sheep serum to target these Th cells to the kidney and applied KINK-1 selectively in the effector phase (experimental plan is in Figure 3A). Surprisingly, in this setting, aNTN was markedly and consistently aggravated, which was evident by more severe histologic kidney damage (Figure 3, B–D, compare the first two experimental groups), lower creatinine clearance, more elevated BUN, and higher proteinuria (Figure 3, E–G). There were more F4/80+ immune cells (Figure 3H), intrarenal DCs were more activated (Figure 3I), and more activated IFNγ+ Th cells were detected (Figure 3J). Anti–sheep Ig titers as a parameter for the nephritogenic Th1 cell response were increased as well (Figure 3K).

Figure 3.

IKK2 inhibition aggravates aNTN by reducing intrarenal Treg cells. (A–K) Therapeutic IKK2 inhibition was performed in the effector phase of accelerated cGN. (A) When indicated, Treg cells were depleted using DT in DEREG mice as shown in the experimental plan. (B) Representative periodic acid–Schiff–stained glomeruli, (C) percentage of crescentic glomeruli, (D) tubulointerstitial injury, (E) creatinine clearance, (F) BUN, (G) albumin-to-creatinine ratio, (H) number of F4/80+ immune cells counted on sections per high-power field (hpf), (I) expression of the DC activation markers CD40 and CD80, (J) numbers of activated and percentages of IFNγ–producing Th cells, and (K) serum anti–sheep IgG titers. (L–N) Number of intrarenal Treg cells in the experiments shown in Figures 1 and 2 and A–K, respectively. Data are representative of four independent experiments (n=5; post hoc analysis by ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test). cGN, crescentic glomerulonephritis; DT, diphtheria toxin; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; NTS, nephrotoxic serum. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

Importantly, we noted that intrarenal Treg cells (gating strategy is in Supplemental Figure 2) were less frequent in both pNTN and aNTN when the KINK-1 was given six times (Figure 3, L and N) but that only a slight and nonsignificant reduction was seen in the therapeutic pNTN setting with only three applications (Figures 2 and 3M). Because Treg cells are well documented to suppress pNTN and aNTN26–29 and because the thymic generation of Treg cells requires IKK2,4,14–16 we hypothesized that KINK-1 might have targeted these cells.

We tested this hypothesis by treating DEREG mice, in which Treg cells can be conditionally depleted, with KINK-1 (experimental setting is in Figure 3A, all four groups). Both Treg depletion and IKK2 inhibition aggravated aNTN, but no additive aggravation was seen when these procedures were combined (Figure 3, B–G, all four groups). Likewise, the parameters for intrarenal inflammation (Figure 3, H–J) and anti–sheep Ig titers (Figure 3K) were increased by Treg depletion and IKK2 inhibition, but no synergy between these maneuvers was evident. Thus, therapeutic IKK2 inhibition aggravated aNTN but was unable to further increase damage when Treg cells were absent, indicating that KINK-1 aggravated aNTN by reducing Treg numbers.

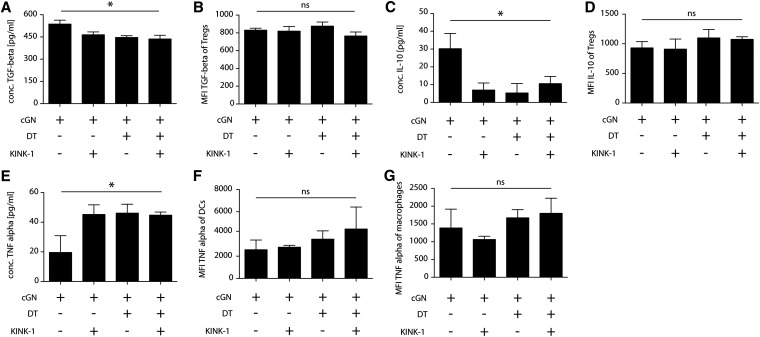

Finally, we examined the mechanisms by which Treg cells can suppress immune responses. After KINK-1 application and after Treg depletion, less TGF-β and less IL-10 was detectable in kidney digests, but no additive effect of these measures was noted (Figure 4, A and C, Supplemental Figure 3). As a control, we measured the NFκB–dependent inflammatory cytokine TNFα and found that it was increased after both maneuvers but again, not synergistically (Figure 4E, Supplemental Figure 3). Intracellular levels of neither TGF-β or IL-10 in Treg cells (Figure 4, B and D) nor TNFα in DCs or macrophages (Figure 4, F and G) were significantly changed, indicating that KINK-1 acted by reducing either the numbers of cytokine–producing immune cells or hypothetic cytokine production by nonimmune cells.

Figure 4.

Intrarenal cytokine milieu after IKK2 inhibition in aNTN. (A and B) TGF-β, (C and D) IL-10, and (E–G) TNFα levels in (A, C, and E) whole-kidney digests measured by ELISA or Luminex and (B and D) Treg cells, (F) DCs, and (G) macrophages measured by intracellular flow cytometry. Data are representative of two independent experiments (n=4; post hoc analysis by ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test). cGN, crescentic glomerulonephritis; DT, diphtheria toxin; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity. *P<0.05.

In summary, our study shows diametrical consequences of prophylactic and therapeutic in vivo inhibition of IKK2: prophylactic inhibition prevented DC and Th cell activation, consistent with the widely accepted view that the NFκB pathway is proinflammatory.2,3,19 Prophylactic inhibition over at least 1 week suppressed Treg cells as well, but this was inconsequential; there was no nephritogenic immune response that Treg cells would have to regulate, because the Th effector cells had not been properly activated. However, when we applied the IKK2 inhibitor in a realistic disease situation (i.e., after Th cell activation), which mimics the situation of patients presenting with ongoing crescentic GN, the suppression of Treg cells was able to unleash the preexisting nephritogenic Th cell response, and disease was aggravated.

We conclude that IKK2 inhibition is anti-inflammatory only when initiated before disease onset, which is impractical for clinical use. Therapeutic IKK2 inhibition has potential proinflammatory consequences, because it compromises the regulation of pathogenic immune responses through Treg cells, and this function prevails over the anti-inflammatory effect resulting from inhibiting DC maturation. These findings highlight the need for in vivo studies in which a complex pathway, such as NFκB, can exert antagonistic functions in different cell types or at different time points. Our findings imply that great care is necessary in clinical studies aiming to treat chronic kidney inflammation by NFκB inhibition, at least when IKK2 inhibitors are used, because these might aggravate rather than ameliorate disease. Our findings may apply to immune-mediated diseases affecting other organs as well.

Concise Methods

Mice and Reagents

Mice were bred at the animal facilities of the University Hospital Bonn and University Hospital Hamburg Eppendorf under specific pathogen–free conditions. Animal experiments were performed according to national and institutional animal care and ethical guidelines and had been approved by government committees (Behörde für Gesundheit und Verbraucherschutz BGV der Freien und Hansestadt Hamburg and Landesamt für Natur and Umwelt und Verbraucherschutz Nordrhein-Westfalen). Treg cells were depleted in nephritic DEREG mice by injecting 15 ng/g body wt diphtheria toxin.27,28 KINK-1 is an ATP–competitive selective IKK2 kinase inhibitor.7 KINK-1 was dissolved in 10% cremophor (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) diluted with PBS. A KINK-1 dose of 5 mg/kg body wt subcutaneously every second day inhibited IKK2 in mice.

pNTN and aNTN Models

pNTN was induced in 8- to 10-week-old age– and sex–matched male mice (20–25 g body wt; Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) on the C57BL/6J background by intraperitoneal injection of 2.5 mg/kg body wt sheep anti–mouse glomerular basement membrane antiserum (nephrotoxic nephritis serum) as described.24 Controls received an equal amount of nonspecific sheep IgG. In aNTN, mice were injected on day −5 with 2.5 mg/kg body wt sheep IgG in incomplete Freund's adjuvant subcutaneously and day 0 with 2 mg/kg body wt nephrotoxic nephritis serum intraperitoneally. This dose caused intermediate disease severity, and doses ≥2.5 mg/kg body wt caused complete renal failure after 2 weeks. Urine was collected in metabolic cages for 24 hours, and serum was derived from whole blood after cardiac puncture. Urinary creatinine, serum creatinine, and BUN were measured using standard methods in the central laboratory of Bonn University Hospital.24 Albuminuria (Mice Albumin Kit; Bethyl) and serum IgG (Dianova) were determined by ELISA.

Histology

Renal tissue injury was assessed in 2-µm paraformaldehyde (4%)–fixed paraffin tissue sections stained by periodic acid–Schiff reaction. A semiquantitative score for acute glomerular injury was assessed in 30 glomeruli per mouse by a double-blinded observer as described before.28 Kidney damage was histologically scored by an observer blinded to the identity of samples. For determining the proportion of crescentic glomeruli, ≥80 glomeruli per section were examined. F4/80+ cells were stained using rabbit antibody to F4/80 (MCA497B; Serotec) diluted 1:50. F4/80+ cell infiltration was then quantified using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). Light microscopic evaluation was performed under an Axioskop (Carl Zeiss GmbH, Jena, Germany) and photographed with an Axiocam HRc (Carl Zeiss GmbH) using the Axiostar software (Carl Zeiss GmbH). F4/80+ cells in 30 tubulointerstitial high–power fields per kidney were counted by light microscopy.

Flow Cytometry

Complete kidneys and spleens were digested with collagenase (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) and DNAse-I as previously described.30 Single-cell suspensions were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies in PBS containing 10% FCS. The following antibodies from BD Pharmingen or eBioscience (San Diego, CA) were used: CD4 (GK1.5), anti-CD45 (30F11), CD8 (53–6.7), B220 (RA3–6B2), CD25 (PC61.5), forkhead/winged–helix box P3 (FJK-16S), CD11c (HL3), MHC-II (M5/114.15.2), F4/80 (BM8), Gr1 (RB6–8C5), CD40 (3/23), CD69 (1H.2F3), CD80 (16–10A1), and anti-IFNγ (XMG1.2). Dead cells were excluded by staining with the LIVE/DEAD Fixable Violet Dead Cell Stain Kit. Viable CD11c+ MHC II+ cells were considered DCs. Intracellular staining was performed as recently described.13 Cells were analyzed with a BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA) LSRII using Diva and FlowJo software. Kidney single–cell suspensions were overnight restimulated with 25 µg/ml sheep Ig, and then, concentrations of TGF-β, IL-10, and TNFα were measured by ELISA or Luminex according to the manufacturer’s instructions (eBioscience).

Nuclear Fractionation and Gel Shift Experiment

Kidneys were perfused with 50 ml sterile PBS per animal before harvesting. Nuclear miniature extracts were prepared, and gel shift assays were carried out using an NFκB oligonucleotide probe (Promega, Heidelberg, Germany) end labeled with 32P-γ-ATP (3000 Ci/mmol; GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI). Afterward, 30 µg nuclear protein was incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature with 100,000 cpm probe in 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 0.3 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM EGTA, 80 mM NaCl, and 2 µg poly(dI-dC)poly(Di-dC) (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) in a total volume of 20 µl. Where indicated, competition experiments were performed by adding unlabeled consensus oligonucleotides in a 100-fold molar excess to the binding reaction. The DNA-protein complexes were separated by electrophoresis and autoradiographed at −80°C for 1 week. Exposed films were quantified using a phosphoimager Bio-Rad GS-363 (multianalyst software; Hercules, CA) and corrected to the density of the probe.

Statistical Analyses

Results are expressed as means±SEM. Differences between experimental groups were compared by either the Kruskal–Wallis test with post hoc analysis using the Mann–Whitney test or one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni test of selected groups (GraphPad Prism Software; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Paired t test was used to compare mean values within one experimental series. No randomization or exclusion of data points was used. Statistical significance was defined as P<0.05. Experiments yielding insufficient data for statistical analysis because of the experimental setup were repeated at least three times. Tests were reported only where data met assumptions of tests. On the basis of preliminary experimental data, a power analysis of 0.8 with P<0.05 indicates a minimum number of three samples/purifications per group, but in some cases, four samples/purifications per group were used.

Disclosures

K.Z. is a full-time employee and stockholder of Bayer AG (Berlin, Germany). The other authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Chrystel Flores and Anna Kaffke for excellent technical assistance and Tim Sparwasser for DEREG mice. C.K. is a member of the Excellence Cluster ImmunoSensation.

We acknowledge technical support from the Central Animal Facilities and the Flow Cytometry Core Facilities of the Medical Faculties both in Bonn and in Hamburg. This work was funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grants KFO228 and SFBTR57, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Price (to C.K.), and the European Union Consortia INTRICATE and RELENT.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2015060699/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Oh H, Ghosh S: NF-κB: Roles and regulation in different CD4(+) T-cell subsets. Immunol Rev 252: 41–51, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vallabhapurapu S, Karin M: Regulation and function of NF-kappaB transcription factors in the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol 27: 693–733, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinman RM, Bonifaz L, Fujii S, Liu K, Bonnyay D, Yamazaki S, Pack M, Hawiger D, Iyoda T, Inaba K, Nussenzweig MC: The innate functions of dendritic cells in peripheral lymphoid tissues. Adv Exp Med Biol 560: 83–97, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerondakis S, Fulford TS, Messina NL, Grumont RJ: NF-κB control of T cell development. Nat Immunol 15: 15–25, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gasparini C, Feldmann M: NF-κB as a target for modulating inflammatory responses. Curr Pharm Des 18: 5735–5745, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McIntyre KW, Shuster DJ, Gillooly KM, Dambach DM, Pattoli MA, Lu P, Zhou XD, Qiu Y, Zusi FC, Burke JR: A highly selective inhibitor of I kappa B kinase, BMS-345541, blocks both joint inflammation and destruction in collagen-induced arthritis in mice. Arthritis Rheum 48: 2652–2659, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ziegelbauer K, Gantner F, Lukacs NW, Berlin A, Fuchikami K, Niki T, Sakai K, Inbe H, Takeshita K, Ishimori M, Komura H, Murata T, Lowinger T, Bacon KB: A selective novel low-molecular-weight inhibitor of IkappaB kinase-beta (IKK-beta) prevents pulmonary inflammation and shows broad anti-inflammatory activity. Br J Pharmacol 145: 178–192, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pasparakis M, Haase I, Nestle FO: Mechanisms regulating skin immunity and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 14: 289–301, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malato Y, Sander LE, Liedtke C, Al-Masaoudi M, Tacke F, Trautwein C, Beraza N: Hepatocyte-specific inhibitor-of-kappaB-kinase deletion triggers the innate immune response and promotes earlier cell proliferation during liver regeneration. Hepatology 47: 2036–2050, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baratin M, Foray C, Demaria O, Habbeddine M, Pollet E, Maurizio J, Verthuy C, Davanture S, Azukizawa H, Flores-Langarica A, Dalod M, Lawrence T: Homeostatic NF-κB signaling in steady-state migratory dendritic cells regulates immune homeostasis and tolerance. Immunity 42: 627–639, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gavin MA, Rasmussen JP, Fontenot JD, Vasta V, Manganiello VC, Beavo JA, Rudensky AY: Foxp3-dependent programme of regulatory T-cell differentiation. Nature 445: 771–775, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sakaguchi S, Yamaguchi T, Nomura T, Ono M: Regulatory T cells and immune tolerance. Cell 133: 775–787, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gotot J, Gottschalk C, Leopold S, Knolle PA, Yagita H, Kurts C, Ludwig-Portugall I: Regulatory T cells use programmed death 1 ligands to directly suppress autoreactive B cells in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109: 10468–10473, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt-Supprian M, Tian J, Grant EP, Pasparakis M, Maehr R, Ovaa H, Ploegh HL, Coyle AJ, Rajewsky K: Differential dependence of CD4+CD25+ regulatory and natural killer-like T cells on signals leading to NF-kappaB activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101: 4566–4571, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Long M, Park SG, Strickland I, Hayden MS, Ghosh S: Nuclear factor-kappaB modulates regulatory T cell development by directly regulating expression of Foxp3 transcription factor. Immunity 31: 921–931, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gückel E, Frey S, Zaiss MM, Schett G, Ghosh S, Voll RE: Cell-intrinsic NF-κB activation is critical for the development of natural regulatory T cells in mice. PLoS One 6: e20003, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dissanayake D, Hall H, Berg-Brown N, Elford AR, Hamilton SR, Murakami K, Deluca LS, Gommerman JL, Ohashi PS: Nuclear factor-κB1 controls the functional maturation of dendritic cells and prevents the activation of autoreactive T cells. Nat Med 17: 1663–1667, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brüstle A, Brenner D, Knobbe CB, Lang PA, Virtanen C, Hershenfield BM, Reardon C, Lacher SM, Ruland J, Ohashi PS, Mak TW: The NF-κB regulator MALT1 determines the encephalitogenic potential of Th17 cells. J Clin Invest 122: 4698–4709, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayden MS, Ghosh S: NF-κB, the first quarter-century: Remarkable progress and outstanding questions. Genes Dev 26: 203–234, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silva GE, Costa RS, Ravinal RC, Ramalho LZ, Dos Reis MA, Coimbra TM, Dantas M: NF-kB expression in IgA nephropathy outcome. Dis Markers 31: 9–15, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brähler S, Ising C, Hagmann H, Rasmus M, Hoehne M, Kurschat C, Kisner T, Goebel H, Shankland S, Addicks K, Thaiss F, Schermer B, Pasparakis M, Benzing T, Brinkkoetter PT: Intrinsic proinflammatory signaling in podocytes contributes to podocyte damage and prolonged proteinuria. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 303: F1473–F1485, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tipping PG, Holdsworth SR: T cells in crescentic glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 1253–1263, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kurts C, Panzer U, Anders HJ, Rees AJ: The immune system and kidney disease: Basic concepts and clinical implications. Nat Rev Immunol 13: 738–753, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hochheiser K, Heuser C, Krause TA, Teteris S, Ilias A, Weisheit C, Hoss F, Tittel AP, Knolle PA, Panzer U, Engel DR, Tharaux PL, Kurts C: Exclusive CX3CR1 dependence of kidney DCs impacts glomerulonephritis progression. J Clin Invest 123: 4242–4254, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schön M, Wienrich BG, Kneitz S, Sennefelder H, Amschler K, Vöhringer V, Weber O, Stiewe T, Ziegelbauer K, Schön MP: KINK-1, a novel small-molecule inhibitor of IKKbeta, and the susceptibility of melanoma cells to antitumoral treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst 100: 862–875, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolf D, Hochegger K, Wolf AM, Rumpold HF, Gastl G, Tilg H, Mayer G, Gunsilius E, Rosenkranz AR: CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells inhibit experimental anti-glomerular basement membrane glomerulonephritis in mice. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 1360–1370, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ooi JD, Snelgrove SL, Engel DR, Hochheiser K, Ludwig-Portugall I, Nozaki Y, O’Sullivan KM, Hickey MJ, Holdsworth SR, Kurts C, Kitching AR: Endogenous foxp3(+) T-regulatory cells suppress anti-glomerular basement membrane nephritis. Kidney Int 79: 977–986, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paust HJ, Ostmann A, Erhardt A, Turner JE, Velden J, Mittrücker HW, Sparwasser T, Panzer U, Tiegs G: Regulatory T cells control the Th1 immune response in murine crescentic glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int 80: 154–164, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ostmann A, Paust HJ, Panzer U, Wegscheid C, Kapffer S, Huber S, Flavell RA, Erhardt A, Tiegs G: Regulatory T cell-derived IL-10 ameliorates crescentic GN. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 930–942, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krüger T, Benke D, Eitner F, Lang A, Wirtz M, Hamilton-Williams EE, Engel D, Giese B, Müller-Newen G, Floege J, Kurts C: Identification and functional characterization of dendritic cells in the healthy murine kidney and in experimental glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 613–621, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.