Abstract

The number of phonological neighbors to a word (PND) can affect its lexical planning and pronunciation. Similar parallel effects on planning and articulation have been observed for other lexical variables, such as a word’s contextual predictability. Such parallelism is frequently taken to indicate that effects on articulation are mediated by effects on the time course of lexical planning. We test this mediation assumption for PND and find it unsupported. In a picture naming experiment, we measure speech onset latencies (planning), word durations, and vowel dispersion (articulation). We find that PND predicts both latencies and durations. Further, latencies predict durations. However, the effects of PND and latency on duration are independent: parallel effects do not imply mediation. We discuss the consequences for accounts of lexical planning, articulation, and the link between them. In particular, our results suggest that ease of planning does not explain effects of PND on articulation.

Keywords: language production, lexical planning, articulation, neighborhood density, confusability

Introduction

The link between the lexical planning of speech and articulation continues to play an important theoretical role in our understanding of speech production. Yet, its nature remains poorly understood. A priori, three aspects of speech production can be distinguished: the process of planning (e.g. lexical and phonological retrieval processes), the articulatory plan generated by planning processes (which depends not only on the process, but also the representations that it operates over), and the execution of the plan (i.e. articulation). Research in language production has largely focused on the relation between the first and the last aspect. An increasingly common theoretical position is that the process of planning is directly reflected in the articulatory plan and consequently in articulation and thus pronunciation (cf. Arnold & Watson, 2015; Goldrick, Vaughn, & Murphy, 2013; Kahn & Arnold, 2015; Kello, 2004; Kirov & Wilson, 2013; Watson, Buxó-Lugo, & Simmons, 2015). We will refer to this as the planning-drives-articulation hypothesis. Some accounts go further and propose that any systematic variation in articulation stems exclusively from variation in the course of planning and retrieving a word’s representation. For example, Kahn and Arnold (2012), aiming to account for effects of givenness on acoustic realization, propose that

[…] acoustic reduction […] emerges from facilitation of the mechanisms of production. We hypothesize that reduction results from some combination of (1) activation of the conceptual and linguistic representations associated with a word, and (2) facilitation of any of the processes associated with generating an articulatory plan from a concept. Kahn and Arnold, 2012, p. 313

According to this view, changes in a word’s pronunciation due to contextual givenness are thus assumed to wholly originate in facilitation of any of the representations or encoding processes involved in planning (see also Bard et al., 2000). Similar accounts have been proposed for changes in pronunciation due to priming (Balota, Boland, & Shields, 1989; Bell, Brenier, Gregory, Girand, & Jurafsky, 2009; Kello, 2004) and Stroop tasks (Kawamoto, Kello, Higareda, & Vu, 1999; Kello, 2004; Kello, Plaut, & MacWhinney, 2000). Similar assumptions about the link between lexical planning and articulation are increasingly accepted in psycholinguistic research (for citations, see Arnold, 2008; Balota et al., 1989; Bard et al., 2000; Bell et al., 2009; Kahn & Arnold, 2012, 2015; Lam & Watson, 2010; MacDonald, 2013; Watson et al., 2015).

Yet, despite the central role of the planning-drives-articulation hypothesis, direct tests of the hypothesis have largely been lacking. Previous evaluations of the planning-drives-articulation hypothesis have relied on indirect evidence. Specifically, one common argument is based on evidence that some lexical or task properties affect both production planning and articulation in similar ways (e.g., Balota et al., 1989; Fox, Reilly, & Blumstein, 2015; Gahl, Yao, & Johnson, 2012; Kahn & Arnold, 2012; Kello, 2004; Kello et al., 2000). However, such parallel effects are insufficient to argue that effects on articulation are mediated through lexical planning (the central claim of the production-drives-articulation view). Indeed, as we show below, parallel effects can arise in the absence of mediation. It is thus necessary to test the central prediction made by the planning-drives-production view: differences in lexical planning should be reflected in similar differences in articulation (and thus pronunciation), and possibly, all systematic variation in articulation should be mediated by, and reducible to, lexical planning.

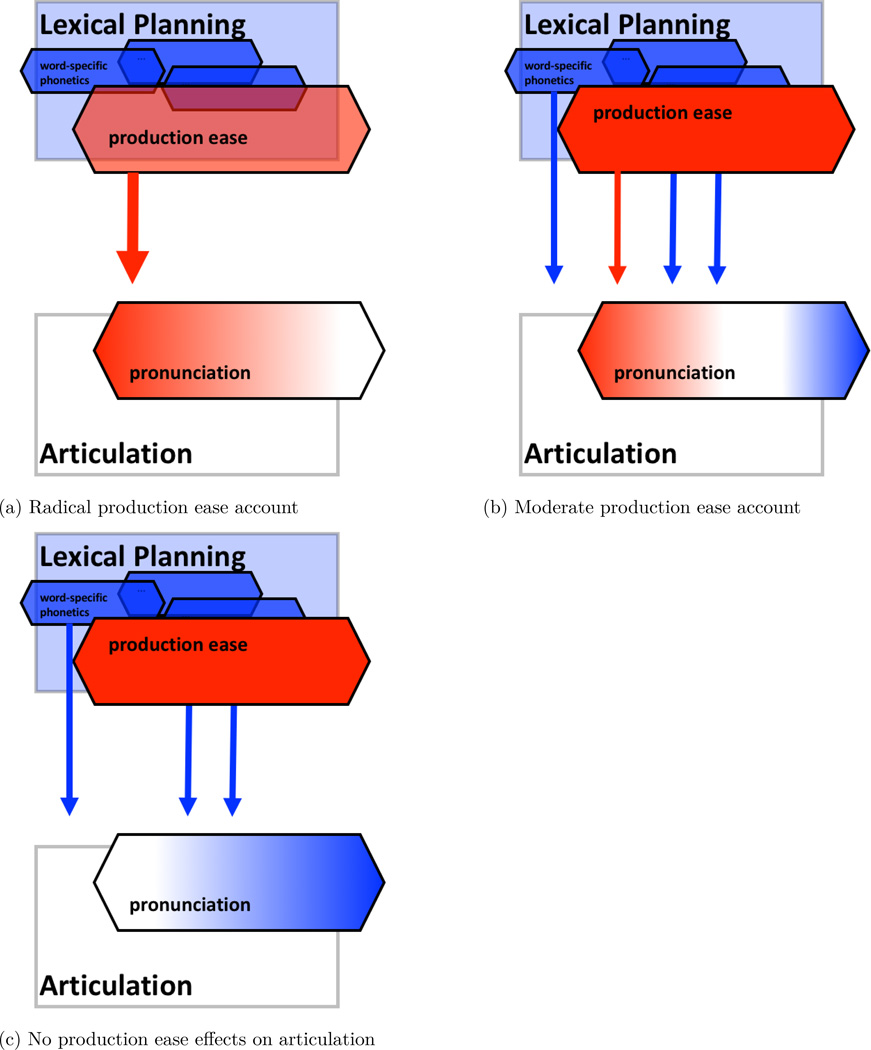

The present work contributes to recent attempts to address this gap in the literature (Heller & Goldrick, 2014; Munson, 2007; Watson et al., 2015). We focus on a lexical property that has received much attention in the lexical planning and articulation literature, phonological neighborhood density (PND). Before we introduce the relevant literature on PND, we briefly elaborate on the type of account we aim to test and how we aim to test it. Specifically, there are two broad classes of accounts inspired by the planning-drives-articulation perspective. Competition accounts hold that increased competition during lexical planning leads to increased articulatory detail (Fox et al., 2015; Goldrick et al., 2013; Kirov & Wilson, 2013; see also Kello et al., 2000, for a cascading activation approach). Since competition is not a directly observable quantity, these accounts require further specification before they begin to make testable predictions about the planning-articulation link (for a more detailed critique of these accounts, see Jaeger & Buz, 2016). For example, it is sometimes argued that planning latencies are not necessarily a measure of the competition experienced during lexical planning (Damian, 2003; Mahon, Costa, Peterson, Vargas, & Caramazza, 2007, also Goldrick, p.c.). We thus postpone any further treatment of competition accounts to the Discussion. The second class of accounts holds that reduced production difficulty results in reduced pronunciations (Arnold & Watson, 2015; Bard et al., 2000; Bell et al., 2009; Kahn & Arnold, 2012; Watson et al., 2015). Such production ease accounts predict that (1) faster planning will result in less articulatory detail (Kahn & Arnold, 2015; see also Kirov & Wilson, 2013). A radical production ease account further predicts that (2) only production ease should systematically affect pronunciation. Figure 1 illustrates radical and moderate production ease accounts (Panel a and b) and contrasts them with the absence of production ease effects on articulation (Panel c). With these clarifications in mind we now turn to the literature on PND.

Figure 1.

Possible relations between production ease and articulation. Panel (a): Radical production ease predicts that any systematic (i.e., non-random) variation in articulation is caused by production ease. Panel (b): Moderate production ease accounts predict that production ease is one of several factors that cause systematic variation in articulation. Panel (c): It is also possible that articulation is not affected by production ease.

PND has received considerable attention in psycholinguistic research on both comprehension and production (for recent overviews, see, Chen & Mirman, 2012; Sadat, Martin, Costa, & Alario, 2014). Of interest here is that PND has been found to affect both the planning (Chen & Mirman, 2012; Heller & Goldrick, 2014; Sadat et al., 2014; Vitevitch, 2002; Vitevitch & Luce, 1999; Vitevitch & Sommers, 2003; Vitevitch & Stamer, 2006) and pronunciation of spoken words (Fox et al., 2015; Gahl et al., 2012; Munson, 2007; Munson & Solomon, 2004; see also Scarborough, 2010, 2012, 2013; Scarborough & Zellou, 2013; Wright, 2004; for a critique of some of these latter studies, see Gahl, 2015).1 For instance, one line of studies presented in Sadat et al. (2014) found that words with few phonological neighbors (low PND words) are planned more quickly than words with many phonological neighbors (high PND words; see also Vitevitch & Stamer, 2006). A separate line of studies found that low PND words are articulated with less detail than high PND words (Fox et al., 2015; Munson, 2007; Munson & Solomon, 2004; Scarborough, 2010, 2012, 2013; Scarborough & Zellou, 2013; Wright, 2004). This would seem to suggest a positive correlation between the amount of time required for lexical planning and the amount of detail provided during articulation, with faster planning resulting in less articulatory detail. Such a positive correlation has been taken as evidence for production ease accounts (Gahl et al., 2012; for similar arguments for the reduction of predictable or repeated instances of words, see, Arnold, 2008; Bard et al., 2000; Bell et al., 2009).

However, there are at least two problems with this argument. First, parallel effects of PND on planning and articulation are at best indirect evidence in favor of the planning-drives-production view. At worst, parallel effects can arise in the complete absence of mediation. Second, the empirical landscape is less clear than the above paragraph suggests. For example, some studies have found the converse relationship between PND and planning, that low PND words are planned more slowly (Munson, 2007; Vitevitch, 2002; Vitevitch & Luce, 1999). Other work has found the converse relationship between PND and pronunciation, that low PND words are pronounced with more detail (Gahl et al., 2012). An arguably bigger problem, however, is that almost all existing studies have focused on the role of PND in either planning or articulation. This means that arguments for or against specific claims about the planning-articulation link have relied on comparisons across studies that differ along many dimensions (e.g., some studies employed picture description, others employed reading tasks, some involve distinct languages, yet others were based on data from conversational speech).

In fact, we are aware of only a single study that investigated effect(s) of PND on planning and articulation under the same conditions (Munson, 2007; for related work, see Heller & Goldrick, 2014, who investigate noun density rather than PND). In a word reading study, Munson had speakers read aloud words either immediately upon presentation or with some delay. Munson also manipulated the lexical frequency and (frequency-weighted) PND of target words. Munson argued that any effect on articulation that is mediated through planning should be reduced in the delayed speech condition. This reduction was indeed observed for the effects of frequency on articulation, but not for the effects of PND on articulation: PND effects on articulation did not differ between the immediate and the delayed condition. Munson took this to argue that frequency, but not PND, effects on articulation are mediated through planning.

Munson further presented a regression analysis meant to directly test whether the effect of PND on articulation is mediated through lexical planning. Munson found that PND explained variation in pronunciation, even while effects of planning latency were simultaneously controlled for. These results are compatible with a link between production planning and articulation (prediction (1) above), but reject the radical production ease account (prediction (2) above). In particular, these results suggest that PND effects on articulation are not fully mediated through lexical planning but may stem from some other source.

However, since its publication, several potential problems have been identified with Munson’s study. First, the regression analysis Munson conducted collapsed over data from both the immediate and the delayed condition. It is possible that planning latencies in the delayed condition do not provide a good measure of the actual time course of lexical planning (the delay was always 1000 ms and thus predictable, potentially allowing advance planning). Thus collapsing over the immediate and delayed condition under estimates the effect of planning latencies on articulation, biasing Munson’s test against production ease accounts.

Second, as has recently been discussed (Gahl, p.c.; Munson, p.c.), the stimuli used in Munson (2007) confounded PND with other phonological properties known to affect articulation (for a discussion, see Gahl, 2015). Third and finally, Munson’s analysis leaves open whether the effects of PND on articulation are at least partially mediated through lexical planning.

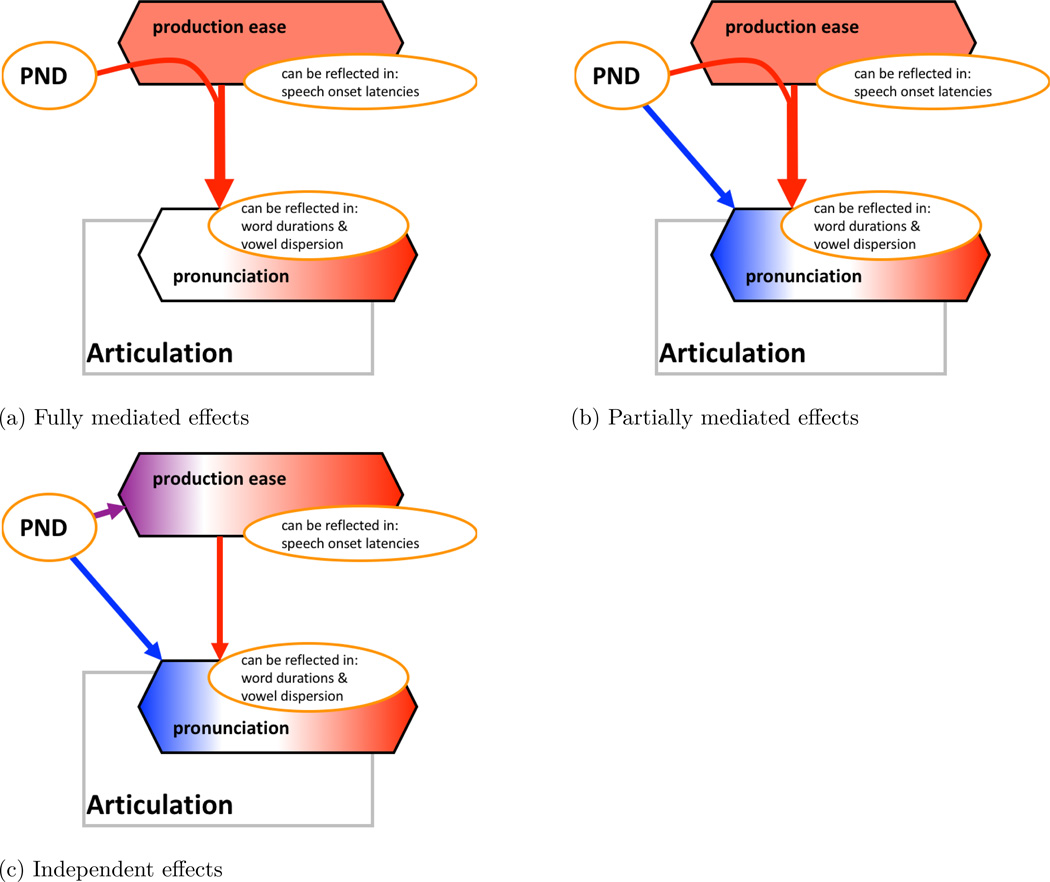

Consider Figure 2, which illustrates possible links between PND, lexical planning, and articulation under production ease accounts. (Note that Figure 2 is a simplification; in particular, different aspects of planning and articulation—reflected in different behavioral measures—might exhibit different dependencies.) Figure 2a illustrates the prediction under radical production ease accounts, where the influence of PND on articulation is fully mediated through lexical planning (i.e. if PND reduces lexical planning time, it also reduces pronunciation detail). The findings of Munson (2007), if confirmed, would argue against this account. Even if these findings are confirmed, however, this leaves open whether the influence of PND on articulation is completely independent of planning (see Figure 2c) or partially mediated through planning (as argued under moderate production ease accounts, see Figure 2b). The former case would describe a moderate production ease account of PND effects on articulation. The latter possibility, too, is compatible with moderate production ease accounts, but would imply that production ease does not contribute to PND effects on articulation.

Figure 2.

Some possible influences of PND on lexical planning and articulation under production ease accounts. In all of (a)-(c), production ease affects articulation. The panels differ, however, in the extent to which production ease explains effects of PND on articulation. Panel (a) shows the prediction of radical production ease accounts: the effect of PND on articulation is fully mediated by its effect on planning (e.g. if PND reduces lexical planning time it also reduces pronunciation detail). Panels (b) and (c) show the predictions of two different types of moderate production ease accounts. In (b), production ease explains some of the effect of PND on articulation: there are both an independent and mediated effects of PND on articulation. In (c), production ease affects articulation, but the effect of PND is independent of that.

In summary, while the study reported in Munson (2007) is of central importance to our understanding of the link between planning and articulation, it leaves open important questions. This motivates the current work. We investigate the effect of PND on lexical planning and articulation, as well as the link between them, while addressing the confounds that have been identified since the publication of Munson’s study. We use minimal pair stimuli that allow us to test for differences in PND while controlling, as much as possible, for differences in phonological form. Unlike in Munson (2007), all our data comes from non-delayed productions. Additionally, we balance or control for additional variables that have been identified to affect planning or articulation since Munson (2007). We present trial-level analysis to directly assess the link between planning and articulation (see Sadat et al., 2014, for a similar analysis of PND effects on planning).

The current study also extends Munson’s in two other aspects that facilitate comparison with other work on planning or articulation. First, Munson used a word reading task, whereas most work on the role of PND in lexical planning has relied on picture naming (see Sadat et al., 2014, and references therein). We thus employ a picture naming paradigm. Second, Munson measured vowel dispersion and vowel duration. This contrasts with the majority of studies on the planning-articulation link in other domains, which have focused on word durations (e.g., Arnold, 2008; Bard et al., 2000; Bell et al., 2009; Kahn & Arnold, 2015). We thus measure both vowel dispersion and word duration to facilitate comparison with both Munson (2007) and other work.

To anticipate the outcome of the current study, we find that effects of PND on articulation do not seem to be mediated through effects of PND on planning. This will lead us to discuss alternative explanations for the effect of PND on articulation, including explanations in terms of representational accounts (and, specifically, the production-perception loop of exemplar-based models, e.g., Pierrehumbert, 2002; Wedel, 2006) and accounts that allow articulation to be affected by communicative goals (e.g., Galati & Brennan, 2010; Lindblom, 1990; Schertz, 2013; Stent, Huffman, & Brennan, 2008).

Experiment

In a picture naming experiment, we investigate the effect of log-frequency-weighted PND on the lexical planning and articulation of the same words. Critical items consisted of minimal pairs (car-jar) which differed in log-frequency-weighted PND. This allows us to investigate PND effects when all but one segment of a word is held constant, thereby reducing the a priori expected differences in planning and articulatory measures due to differences in the phonological form.

Methods

Participants

36 University of Rochester undergraduates participated in the experiment. All were self-reported monolingual native English speakers. Participants were compensated $10.

Procedure

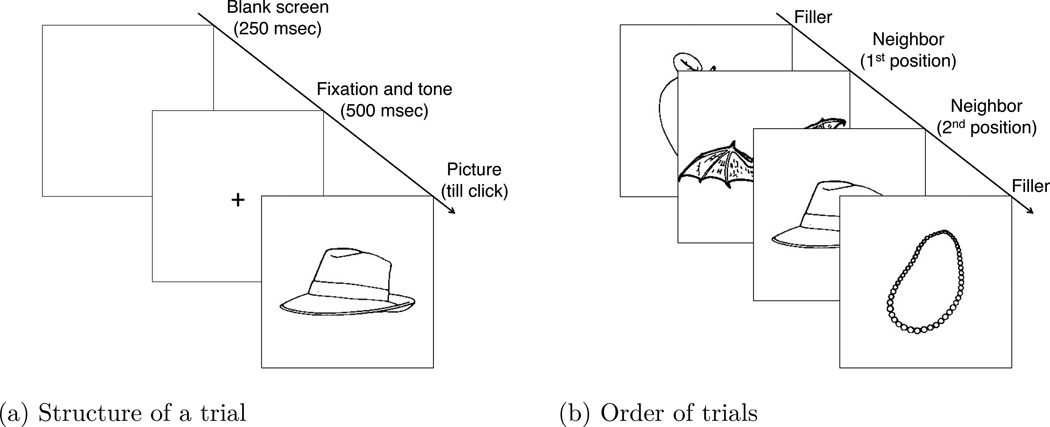

On each trial, participants were presented a picture and had to name it. We instructed participants to name the pictures as quickly as possible. Figure 3a shows a schematic of a trial. Participants initiated each trial with a mouse click. Starting 250 ms later, a fixation cross was displayed at the center of the screen for 500 ms, and a beep tone was played for the first 250 ms. After the 500 ms had passed, the picture appeared centered in the screen. All pictures were 420 by 420 pixels large and displayed on a screen with a resolution of 1680 by 1050 pixels, about 60 cm away from the participant. Participants ended the trial by clicking a mouse button. The experiment lasted no longer than 40 minutes.

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of trial structure (a) and trial ordering within a minimal pair (b) for the picture naming experiment.

Materials

Stimuli to the experiment consisted of 108 line drawings taken from the International Picture Naming Project (IPNP) database (Bates et al., 2003). For all pictures, IPNP norms identified the word we intended participants to produce as the dominant label (> 80% naming accuracy).

Following Munson (2007) and Scarborough (2010, 2012), we binned targets into low vs. high log-frequency-weighted PND. The dominant labels for forty of these targets formed twenty monosyllabic minimal pairs (e.g., car-jar), such that one of the targets had greater log frequency-weighted PND (e.g., car with a log-frequency-weighted PND of 51.08) and the other had lower log-frequency-weighted PND (e.g., jar with log-frequency-weighted PND of 31.08).

Each minimal pair consisted of CVC, CCVC, or CVCC words. To control for possible compression effects, pairs shared a vowel and onset and coda complexity (i.e. targets in a pair either both had single segment codas or both had two-segment codas, following Scarborough, 2010). One pair was CCVC, three were CVCC, and the remainder (36) were CVC. Three pairs differed in the coda and the remainder (37) differed in the onset. Vowels were in the set (/ɑ, æ, ɔ, aƱ, ε, eI, I, oƱ, Ʊ/). These minimal pairs constitute the target items for our study. A complete list of items is provided in Appendix B (Table B1).

Our minimal pair design holds constant syllable, coda, and onset complexity, all of which could influence word durations and vowel dispersion. However, differences in consonant contexts are known to affect vowel duration, specifically voicing and manner (House, 1961). Chi-squared tests of independence show that, across the density groups, our stimuli pairs did not significantly differ in manner (plosive, nasal, fricative, lateral), place (bilabial, labial, labio-dental, alveolar, velar), or voicing (p’s> 0.1). In addition we balanced (log-transformed) frequency, average biphone log probability, number of alternative picture labels for paired pictures, and proportion of usage of the dominant label (no difference assessed by paired t-tests). The mean (and standard deviation) of these measures by high vs. low log-frequency-weighted PND condition are provided in Table 1. We report log-frequency-weighted PND based on IPhOD2, a lexical database of 54,000 tokens of English from the SUBTLEXus corpus (Brysbaert & New, 2009). All results reported below replicated robustly when log-frequency-weighted PND was calculated based on CELEX (Baayen, Piepenbrock, & van Rijn, 1993), as in, for example, Scarborough (2010, 2012).

Table 1.

Mean values and standard deviation (SD) of control variables by high vs. low log-frequency-weighted PND. High and low PND words did not differ in these values (paired t-test, p > 0.1).

| PND |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High |

Low |

|||

| mean | SD | mean | SD | |

| (log) Frequency | 1.6 | 0.68 | 1.54 | 0.59 |

| (log) Average biphone probability | 0.0038 | 0.0041 | 0.0032 | 0.0034 |

| IPNP label count | 2.05 | 1.23 | 2.45 | 1.73 |

| Dominance of intended label | 0.95 | 0.06 | 0.95 | 0.06 |

In addition to the 40 minimal pair pictures, there were 60 filler pictures. Fillers were pictures whose dominant labels were mono (9), bi-syllabic (42), tri-syllabic (7), or quadri-syllabic (2). Finally, eight pictures served as practice trials, following instructions and preceding the main session. Fillers and practice labels were chosen as to not be phonological neighbors with any of the critical or filler items.

Two lists were created by pseudo-randomly distributing the 20 minimal pairs across the 100 trials. Each participant saw both target words of a minimal pair item with at least one, but no more than four, fillers appearing between pairs (fillers did not occur between a pair). The order of the two targets within a pair was counter-balanced across the two lists. Each list was seen by 18 participants. Every 25 trials, participants were prompted to take a break (breaks never intervened between neighbor-target pairs). Trials were automatically recorded from mouse click to mouse click. The experimenter sat silently in the recording booth with the participant.

Scoring

The first author transcribed all 100 target and filler pictures for each participant. One participant was removed because of low picture naming accuracy (72%). Naming accuracy of the remaining participants was high (88%). This left 35 participants for the analysis.

We then checked whether participants’ productions corresponded to the intended picture labels. For two minimal pairs, one of the targets had very low intended label usage across participants (bark and rain, <28% intended label usage). Both of these minimal pairs (bark-shark and rain-chain) were removed from the analysis. For the remaining 18 minimal pairs, intended label usage was high (92%).

The remaining 1283 productions were annotated for disfluencies, recording issues, speech onset latencies, and speech rate. We excluded all disfluent target trials and trials in which participants did not produce the intended label (9.7%). We excluded trials with recording issues (e.g., truncation of end of speech, 1.6% data loss). We also removed all target words with (log-transformed) speech onset latencies and (log-transformed) durations that fell outside the mean duration of all words ±2.5 standards deviations, 2.3% data loss). Since we were interested in the difference in duration between minimal pairs, we always removed both targets of a minimal pair if at least one target was removed through the above criteria (11.4% data loss). This left 964 target trials (75.1% of total) from 18 minimal pairs and 35 participants.

The transcriptions created by the experimenter were used as input to forced alignment (Prosodylab-Aligner Gorman, Howell, & Wagner, 2011). The aligner was trained by Kyle Gorman, Jonathan Howell, and Michael Wagner for forced alignment of lab-based speech (as opposed to conversational speech) and has been shown to produce reliable results (Gorman et al., 2011). These alignments were then hand-corrected by an RA trained by the first author. Durations and vowel dispersion were extracted from the corrected alignments. Durations were log-transformed (results hold without this transformation). First and second formant measures were taken at the midpoint of the vowel in each target word. Formant frequencies were converted to the Bark scale with the following formula: B = 26.81/(1 + (1960/f)) – 0.53 where B is bark and f is frequency in Hertz (Traunmüller, 1990). Vowel dispersion for each vowel was calculated as the Euclidean distance from the center of the vowel space (the average first and second formant value for all targets for each speaker) (following Munson, 2007; Munson & Solomon, 2004; Scarborough, 2010, 2012; Scarborough & Zellou, 2013).

Predictions

Production ease accounts predict that differences in lexical planning should be reflected in articulation (and thus in pronunciation). This means that speech onset latencies should correlate with word durations and vowel dispersion (to the extent that either of these articulatory measures exhibit systematic variation). Radical production ease accounts further predict that any systematic pronunciation variation (including effects of PND) is mediated through effects of production planning. Finally, since planning ease is assumed to correlate with reduced pronunciations (or planning difficulty with enhanced pronunciations), production ease accounts of PND predict that PND affects speech onset latencies and articulation in the same way (see Figures 2a,b).

Results

All analyses reported below were conducted using linear mixed regression analyses, with by-subject and by-pair random intercepts and slopes for the PND effect (Baayen, Davidson, & Bates, 2008). Factors were sum-coded, and continuous predictors were centered. P-values are based on the χ2 test over the change in deviance between the models with and without the predictor.

We first analyze the effect of PND on production planning—as assessed by log-transformed speech onset latencies.2 Then we analyze the effect of PND on articulation—as assessed by log-transformed word durations and Bark-transformed vowel dispersion. We then assess directly the relation between production planning (latencies) on articulation (duration and dispersion) and the extent to which whatever effects we observe on articulation can be reduced to production planning. In all of these analyses, we analyze effects of PND by treating it as a binary contrast (high vs. low log-frequency-weighted PND). This follows our experimental design and increases comparability with the majority of previous work (e.g. Baese-Berk & Goldrick, 2009; Kirov & Wilson, 2012; Munson, 2007; Munson & Solomon, 2004; Scarborough, 2010, 2012; Wright, 2004).

Neighborhood density effects on lexical planning

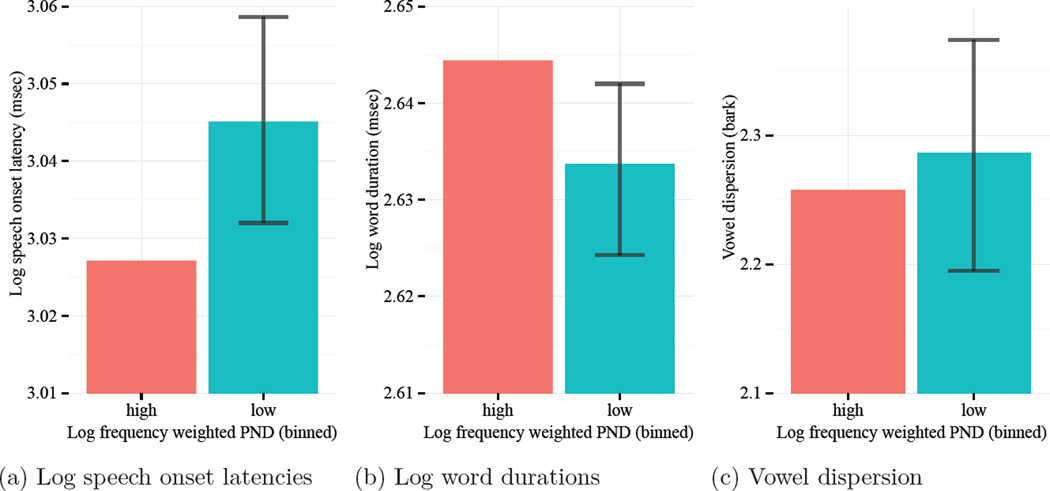

Table 2, Column 1 summarizes the analysis of speech onset latencies. Speakers initiated articulation for high log-frequency-weighted PND targets on average 52.1 ms earlier compared to targets with low log-frequency-weighted PND, as illustrated in Figure 4a. This difference was significant (β̂ = −0.01, t = −2.69, pχ(1)=Δ(−2Λ) = 0.01).

Table 2.

PND models for (log-transformed) speech onset latencies, (log-transformed) word duration, and vowel dispersion.

| Dependent measures |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Log latency | Log duration | Dispersion | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Intercept | −0.001 (0.018) |

−0.002 (0.015) |

0.016 (0.168) |

| high density word | −0.009*** (0.003) |

0.005** (0.002) |

−0.014 (0.023) |

| Log Likelihood | 741.249 | 1,106.728 | −1,098.323 |

| Bayesian Inf. Crit. | −1,434.401 | −2,165.357 | 2,244.744 |

Note: * p<0.1; ** p<0.05; *** p<0.01

Figure 4.

Model estimates of influence of log frequency weighted PND on planning and articulatory measures. Error bar represents 95% bootstrapped confidence interval of group difference.

Neighborhood density effects on articulation

Table 2, Columns 2 and 3, summarizes the analysis of word durations and vowel dispersion. Targets with high log-frequency-weighted PND were on average articulated with 12.7 ms longer duration compared to targets with low log-frequency-weighted PND, as illustrated in Figure 4b. This difference was significant (β̂ = 0.01, t = 2.35, pχ(1)=Δ(−2Λ) = 0.02). Vowels in targets with high log-frequency-weighted PND were on average articulated with 0.03 less dispersion compared to targets with low PND, as illustrated in Figure 4c. This difference was not significant (β̂ = −0.01, t = −0.63, pχ(1)=Δ(−2Λ) = 0.53).

Assessing the (in-)dependence of planning and neighborhood density effects on articulation

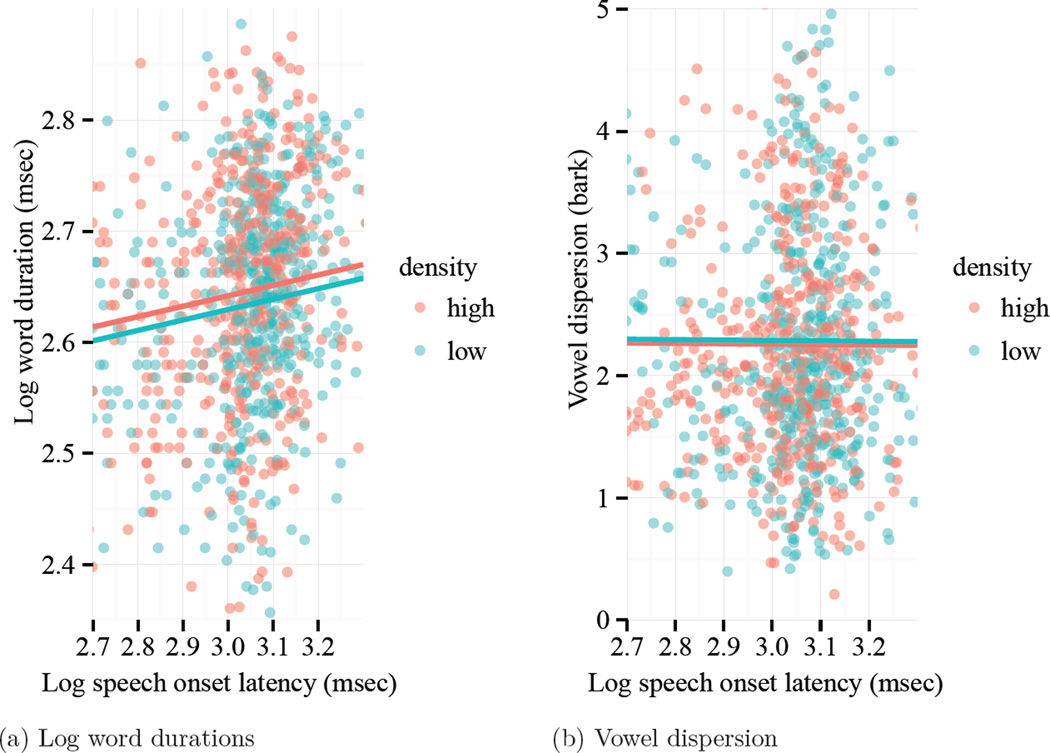

We repeated the analyses of (log-transformed) word durations and (Bark-transformed) vowel dispersion while including (log-transformed) speech onset latencies as a covariate.

The results are summarized in Table 4 and Table visualized in Figure 5. Speech onset latencies had a significant positive effect on word durations (β̂ = 0.09, t = 4.3, pχ(1)=Δ(−2Λ) = 10−4), but did not significantly affect changes in vowel dispersion (β̂ = −0.03, t = −0.15, pχ(1)=Δ(−2Λ) = 0.93). These results did not change if only speech onset latencies were regressed against the articulatory measures (i.e., excluding PND from the analysis).

Table 4.

Effect of (log) speech onset latencies and PND on (log) word durations.

| Dependent measures |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log word duration | Vowel dispersion | |||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Intercept | −0.007 (0.015) |

−0.002 (0.015) |

0.014 (0.168) |

0.016 (0.168) |

| (log) speech onset latency | 0.089*** (0.022) |

0.094*** (0.022) |

−0.020 (0.213) |

−0.033 (0.213) |

| high density word | 0.006*** (0.002) |

−0.015 (0.023) |

||

| Log Likelihood | 1,114.423 | 1,112.930 | −1,096.289 | −1,098.938 |

| Bayesian Inf. Crit. | −2,180.749 | −2,170.890 | 2,240.676 | 2,252.845 |

Note: * p<0.1; ** p<0.05; *** p<0.01

Figure 5.

Raw data and model estimates of influence of log-transformed speech onset latency and log frequency weighted PND on articulatory measures.

Targets with high log-frequency-weighted PND words were still articulated with significantly longer word durations after controlling for speech onset latency (β̂ = 0.01, t = 2.73, pχ(1)=Δ(−2Λ) = 0.01). The effect of log-frequency-weighted PND on vowel dispersion remained non-significant (β̂ = −0.01, t = −0.64, pχ(1)=Δ(−2Λ) = 0.52).

A comparison of the effects of PND on word duration and vowel dispersion, depending on whether speech onset latencies were included in the model (Table 4) or not (Table 2, Columns 2 and 3), further shows that the effects of PND on articulation are orthogonal to the correlation between speech onset latencies and articulation (both the estimated effect sizes of PND and their standard errors remained virtually unchanged). Indeed, the fixed effect correlations between speech onset latency and both word duration and vowel dispersion were very low (fixed effect r < 0.084 and r < 0.086, respectively). This is unexpected under any form of partial or full mediation.

Discussion

We find that higher log-frequency-weighted PND facilitates production planning as reflected in shorter speech onset latencies. We also find that words with greater PND are articulated with more detail, although this is reflected only in longer word durations but not vowel dispersion. Of most relevance for the current purpose is the extent to which planning latencies predict articulatory detail.

We thus begin our discussion with the questions raised in the introduction about the link between lexical planning and articulation. We first address the radical production ease account, according to which all systematic pronunciation variation is determined by production planning. We then turn to the broader claim that production planning is one of several factors that drives articulation. To anticipate the outcome of this discussion, our results provide support for the broader claim (although with some important caveats), but argue against radical production ease accounts. Specifically, our results suggest that the effect of PND on articulation is orthogonal to whatever effect lexical planning has on articulation (supporting the architecture illustrated in Figure 2c).

Following this discussion, we discuss the separate literatures on PND effects on articulation and lexical planning. We begin with the literature on PND effects on articulation. We summarize findings on the relation between PND and pronunciation variation and discuss our results in this context. This leads us to review alternative explanations for the effect of PND on pronunciation in terms of representational accounts (specifically, exemplar-based accounts, Pierrehumbert, 2002) and accounts that allow articulation to be affected by communicative goals (Galati & Brennan, 2010; Lindblom, 1990; Schertz, 2013; Stent et al., 2008). In this context, we also revisit the null result we obtain for vowel dispersion.

Finally, we turn to the role of PND in lexical planning. We review related findings and briefly discuss a potential conflict between our results and previous work.

Is all systematic pronunciation variation determined by lexical planning?

Planning-drives-articulation accounts attribute systematic variation in articulation to differences in production planning. An increasingly common account is that most, if not all, of the systematic variation in articulation is attributable to planning (Arnold, 2008; Balota et al., 1989; Bard et al., 2000; Bell et al., 2009; Kahn & Arnold, 2012; Lam & Watson, 2010; MacDonald, 2013; Watson et al., 2015). Radical production ease accounts predict that effects of PND on articulation are fully—or almost fully—mediated through effects of PND on lexical planning (under the assumption that PND affects lexical planning, illustrated in Figures 2a). Our results provide no support for this prediction. We find that PND affects articulation independent of the effect of planning on articulation (see also Heller & Goldrick, 2014; Munson, 2007). In fact, in the current experiment, the effects of PND on articulation were close to completely orthogonal to its effects on speech onset latencies (as evidence by the fixed effect correlations between PND and speech onset latencies in our analysis of word duration, r < 0.1). Further, words with greater PND were associated with significantly longer word durations, but with shorter speech onset latencies.

These results run precisely counter to the predictions of radical production ease accounts (Figures 2a). Our results are also incompatible with more moderate accounts that attribute effects of PND on articulation to production ease (Figures 2b). Instead, our findings are most consistent with the architecture illustrated in Figure 2c, in which the effects of PND on lexical planning and the effects of PND on articulation are independent.

Beyond the specific role of PND in the planning and execution of speech, the results of the current study raise an important caveat about an increasingly common argument. As we outlined in the introduction, research on the source of pronunciation variation often appeals to parallelism: if a variable affects lexical planning (e.g., speech onset latencies, speech errors, or alike) and also affects articulation, then it is tempting to assume that the latter effect is mediated through the former effect (see, e.g., Bard et al., 2000; Bell et al., 2009; Kahn & Arnold, 2012, 2015; Kello et al., 2000). The appeal of such explanations lies in their parsimony. However, as the current results show, this logic is flawed. Parallel effects are insufficient evidence for mediation.

This problem thus potentially extends to other lines of research that have similarly relied on parallel effects in planning and articulation when arguing for production ease accounts of articulation. This includes, for instance, research on the phonetic reduction of repeated mentions of words (Arnold, 2008; Bard et al., 2000; Jacobs, Yiu, Watson, & Dell, 2015; Kahn & Arnold, 2012, 2015; Lam & Watson, 2010) and the phonetic reduction of frequent or contextually predictable words (Bard et al., 2000; Bell et al., 2009; Kahn & Arnold, 2012, 2015). To the best of our knowledge, direct tests of mediation—as conducted in the current study—are lacking for many of these domains. This includes studies that are explicitly framed as testing the planning-articulation link (e.g. Jacobs et al., 2015; Kahn & Arnold, 2012, 2015; Kello, 2004; Kello et al., 2000; Watson et al., 2015). In fact, some of these studies indirectly provide evidence against the radical production ease accounts. For example, Kahn and Arnold (2012) investigate givenness effects on planning and articulation. They find that givenness indeed facilitates planning (leading to shorter speech onset latencies) and leads to reduced pronunciations (shorter word durations), in line with their hypothesis. However, speech onset latencies did not affect word durations when givenness was controlled for, contrary to what would be expected if givenness effects on articulation are partially or fully mediated through production ease (see also Kahn & Arnold, 2015). Results like these are unexpected under the hypothesis of radical production ease.

Parallelism-based arguments have not been limited to research within the planning-drives-articulation view. For example, interpretations of PND effects on articulation in terms of communicative goals have followed a similar logic (including our own arguments in conversations about this topic). As we detail below, there is some evidence that high PND words are harder to comprehend; combined with findings that high PND words are associated with enhanced pronunciations, this is sometimes taken to argue that enhanced articulations are caused by the goal to be understood. As the current results show, such arguments need to be taken with caution. We return to this point below.

This, together with the current results, highlights the need for further mediation studies of the type conducted here. More specifically, our results call for caution in over-attributing variation in articulation to production ease.

Now that we have established the independence of PND effects on articulation from the time course of lexical planning, we turn to the second prediction of the planning-drives-articulation view. After that we address alternative explanations of the effect of PND on articulation.

Is any systematic pronunciation variation determined by lexical planning?

The second, more general, prediction of the planning-drives-articulation view is that lexical planning affects articulation. Our results support this prediction: we find a positive correlation between speech onset latencies and word durations (see Figure 5a). This replicates a similar finding by Munson (2007) who found that speech onset latencies were correlated with pronunciation variation (see also Heller & Goldrick, 2014; Kahn & Arnold, 2015; but see Tables 2, 3, and 5 in Kahn & Arnold, 2012, who do not find this correlation). These findings are consistent with the idea that production difficulty leads to a slow down in speech rate (e.g., Arnold, Kahn, & Pancani, 2012; Bell et al., 2009; Clark & Fox Tree, 2002; Watson et al., 2015). However, this leaves open the question of how production difficulty comes to affect articulation. We explore two accounts that have been put forward in the literature, production ease and competition based accounts (for further discussion and related accounts, see Jaeger & Buz, 2016).

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of speech onset latencies, word durations and vowel dispersion across conditions.

| PND |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High |

Low |

|||

| mean | SE | mean | SE | |

| Latency (ms) | 1115.5 | 14.36 | 1167.6 | 15.79 |

| Word duration (ms) | 456.0 | 4.86 | 443.3 | 4.44 |

| Dispersion (Bark) | 2.2 | 0.04 | 2.3 | 0.05 |

Previous work has provided ample evidence that production difficulty of upcoming words can affect the realization of the current word, including its duration (Baker & Bradlow, 2009; Bard & Aylett, 2005; Bell et al., 2009; Clark & Fox Tree, 2002; Jaeger, Furth, & Hilliard, 2012a; Watson, Arnold, & Tanenhaus, 2008). More generally, delays in the planning of upcoming words have been found to lead to a variety of strategies, such as inserting disfluencies (Fox Tree & Clark, 1997; Jaeger, 2006) and optional function words (Ferreira & Dell, 2000; Ferreira & Griffin, 2003; Jaeger, 2006, 2010), or changing constituent order so as to postpone production of the problematic word (Arnold, Eisenband, Brown-Schmidt, & Trueswell, 2000; Bock, 1987; Branigan, Pickering, & Tanaka, 2008; Ferreira & Yoshita, 2003; Wasow, 1997). That is, production difficulty of upcoming words is well-known to affect the realization of preceding material. These effects are broadly accepted to stem from a production system that is organized to maintain fluency (availability-based accounts, e.g., the principle of immediate mention in Ferreira & Dell, 2000; for recent discussion, see Jaeger, 2013; MacDonald, 2013).

It is, however, less clear how a production ease account would be extended for the current findings. We observe that speech onset latencies are correlated with word durations even when speakers produce words in isolation (see also Munson, 2007). In our experiment, no material followed the target word. If the observed effect (correlation between speech onset latencies and word durations) is to be attributed to incremental planning, this incrementality would thus be situated within a word. This stands in contrast to the gross of previous work on availability, which has focused on incremental planning between words (cf. Clark & Fox Tree, 2002; Fox Tree & Clark, 1997). Recently, Watson et al. (2015) has extended this idea of incrementality to word-internal planning (see also Kello, 2004; Kello et al., 2000). Specifically, Watson and colleagues propose that the lengthening of a single word’s duration may be to allow for the phonological encoding processes to complete. To test this hypothesis, Watson and colleagues simulated the planning latencies of two multi-syllabic words that either shared their first syllable (e.g. “layover layout”) or their second (e.g. “overlay outlay”). Their model predicts less difficulty in planning the phonologically overlapping syllables. The simulated planning difficulty was then used to predict word durations. Consistent with their model, speakers produced phonologically overlapping syllables with shorter duration. At first blush, this account would thus seem to offer an explanation for the positive correlation between speech onset latencies and word durations in the current experiment. However, all target words in the current experiment were mono-syllabic. Standard accounts of lexical production assume that the minimal units at the interface between phonological encoding and articulation are syllables (cf. Dell, 1986; Levelt, Roelofs, & Meyer, 1999; though see Kawamoto et al., 1999; Wheeldon & Lahiri, 1997). If syllables are indeed the units that incremental phonological planning operates over, then there is no upcoming material left after initiation of articulation of a mono-syllabic word. Thus, additional assumptions would be required to explain changes in speech rate on mono-syllabic words.

An alternative, though not mutually exclusive, view to production ease accounts is offered by competition accounts (Baese-Berk & Goldrick, 2009; Goldrick et al., 2013; see also Kello et al., 2000; Kirov & Wilson, 2013). In competition accounts, target lexical and phonological units compete with alternative lexical and phonological units for selection. The number and relative activation of competing alternatives can influence the final activation of target units at selection time. Competition accounts are motivated by research on the articulation of words with minimal contrast neighbors (e.g., pin - bin). Such words have been found to be hyper-articulated, compared to words without such neighbors (e.g., pipe - *bipe, Baese-Berk & Goldrick, 2009; though see, Fox et al., 2015). Competition accounts attribute this hyper-articulation to greater activation of competing words when lexical selection takes place (cf. Dell, 1986; Levelt et al., 1999).

This explanation has been extended to account for the effect of PND on articulation (Fox et al., 2015): more phonological neighbors are assumed to result in more competition (in line with standard competition accounts of lexical planning, e.g., Dell, 1986; O’Seaghdha & Marin, 2000), which results in higher activation of the target word when lexical selection takes place, which in turn is taken to result in enhanced articulations.3 This prediction matches the current results. Note, however, that this account conflicts—at least at first blush—with another aspect of our findings: we find that PND affects planning and articulation differently, with greater PND resulting in shorter speech onset latencies but longer word durations. While independent competition accounts have been proposed for planning latencies (e.g., Chen & Mirman, 2012; O’Seaghdha & Marin, 2000) and articulation (Baese-Berk & Goldrick, 2009; Goldrick et al., 2013), the link between these two aspects of production has remained under-specified (but see, Kello et al., 2000; Kirov & Wilson, 2013). Chen and Mirman (2012) show that competition accounts predict shorter speech onset latencies for words with more, weakly activated, phonological neighbors, consistent with our results. However, this leaves open why competition should lead to enhanced articulations. Indeed, some competition-like accounts of articulation have made the opposite assumption, that greater PND should lead to longer speech onset latencies (Kirov & Wilson, 2013).

In summary, competition accounts enjoy strong empirical support from research on lexical planning (but see Mahon et al., 2007). This makes them a particularly promising venue to pursue in understanding the link between lexical planning and articulation. However, before competition accounts can be said to make predictions about articulation, future work on these accounts will have to flesh out the link between planning and articulation (for further discussion, see Jaeger & Buz, 2016).

Relating back to the bigger picture question we set out to address, we conclude that our findings argue for a close link between the processes underlying the lexical planning of a words and its articulatory realization. Although further work is necessary to understand the precise nature of this link, our finding thus provides support for the planning-drives-articulation view. At the same time, as discussed above, we find that this link only provides an incomplete picture of the factors that determine how speakers articulate words. We thus turn to the question of what other factors might underlie the observed effect of PND on articulation.

Effects of phonological neighborhood density on articulation

We find that words with greater PND are produced with longer durations. This extends similar findings from previous experiments on PND effects on articulation: in lab-based studies, greater PND has consistently been associated with enhanced pronunciations (vowel dispersion, Munson, 2007; Munson & Solomon, 2004; voice onset timing, Fox et al., 2015).4

To the best of our knowledge, the current study is the first experiment to measure word duration (rather than vowel duration or voice onset time) as a function of PND. One other study has investigated the same effects in a corpus of conversational speech (Gahl et al., 2012). Interestingly, Gahl and colleagues observe the opposite of our findings: in their corpus, words with greater PND are produced with shorter duration and less vowel dispersion. Unfortunately, the large number of methodological differences between the current data and those presented by Gahl and colleagues makes it difficult to compare the results.5 We therefore limit the remaining discussion on studies that have employed methodologies similar to ours (Munson, 2007; Munson & Solomon, 2004).

As discussed above, the effect of PND on word durations does not seem to be mediated through lexical planning (see also Munson, 2007). What then is the cause for the enhanced word durations? We discuss two broad classes of (mutually compatible) accounts, explanation in terms of phonology or word-specific phonetic representations (Johnson, 1997, 2006; Pierrehumbert, 2001) and explanations that appeal to communicative goals (Galati & Brennan, 2010; Jaeger, 2013; Lindblom, 1990, 1996; Schertz, 2013; Stent et al., 2008; Wright, 2004). Then we turn to the second measure of articulation employed in the current study, vowel dispersion. We find no effect of PND on vowel dispersion, although similar previous work has found such effects (Munson, 2007; Munson & Solomon, 2004). We close this section by discussion possible reasons for this null effect and why it may be, in fact, expected under some of the alternative accounts discussed in this section.

Incremental production or phonological representations

Up to this point, we have focused our discussion on accounts that attribute pronunciation variation to the processes underlying lexical planning. Exemplar-based accounts (Johnson, 1997, 2006; Pierrehumbert, 2001) offer an alternative explanation: pronunciation variation could originate in word-specific phonetic representations (e.g., Pierrehumbert, 2002). Indeed, there is empirical support for the hypothesis that phonetic representations can be word-specific (Drager, 2011; Hay, 2001; Johnson, 1997, 2006; Pierrehumbert, 2001). These accounts are compatible with the current findings, but they leave open why, at least on average, words with greater PND would also have representations with longer word durations.

One possible reason is that the detrimental effects that PND (or correlated variables, such as onset density Magnuson, Dixon, Tanenhaus, & Aslin, 2007) have on comprehension makes it less likely that reduced variants of words with greater PND are understood, preventing these reduced exemplars from becoming stored (an idea that dates back to at least Lindblom, 1990; Ohala, 1989; see also Guy, 1996). In the exemplar-based literature, this is referred to as the production-perception loop between interlocutors (Pierrehumbert, 2002; Wedel, 2006). Pierrehumbert (2002) shows that the production-perception loop provides a viable account of the inverse relation between a word’s frequency and the length of its phonological form (Zipf, 1949; see also Manin, 2006; Piantadosi, Tily, & Gibson, 2011). The production-perception loop thus could explain how words with many phonological neighbors over historical time (i.e., within the life-time of an individual or over generations) come to have enhanced phonetics, compared to words with fewer neighbors.

Beyond word-specific phonetics, one might also consider differences in the canonical phonological form between our low and high PND target words as the source of the effects we observe (we thank Susanne Gahl for pointing us to this possibility). Based on a reanalysis of one of the early studies on the effect of PND on articulation (Wright, 2004, going back to earlier reports from 1998), Gahl (2015) illustrates how phonological confounds can cause spurious effects of PND. It was partly problems like these that inspired the design of the current study. With the benefit of hindsight, we aimed to balance phonological and lexical properties between our PND conditions. As detailed in the Materials section, our stimuli were balanced with regard to (log-transformed) frequency and biphone probability (as a measure of phonotactics). Our design further held constant the phonological length and all but one phoneme between minimal pairs. Our exclusion criteria and statistical analyses systematically avoided introducing imbalance into this pair-based design. Finally, we balanced both the voicing and manner of articulation of consonants between PND conditions (see Materials sections for χ2-tests), since both features are known to affect the duration of preceding and following vowels (Crystal & House, 1986; House, 1961).

Still, it is possible that other properties associated with the minimal one-phoneme differences (which—by design—were inevitable) confound our results. To address this possibility, we repeated the word duration analysis reported above while simultaneously including three phonological control variables: we coded whether pairs differed in onset vs. coda, the manner of the contrastive phoneme (nasals, stops, fricatives, approximants, or laterals), and the voicing of the contrastive phoneme. These three predictors as well as all their interactions were added to the analyses reported in the Results section (see Appendix A for details). The PND effect on word durations remained unchanged and significant, suggesting that our results are not due to phonological confounds.

We note that our approach to this question differs from that taken by Gahl (2015). In her reanalysis of Wright (2004), Gahl includes a large set of phonological predictors for the effect of different onsets and codas. We do not follow this approach here since it would violate good statistical practice. Specifically, the current data is not large enough to support such an analysis: to fully model our items based on the phonological features of the onsets, codas and vowel would require 36 main effects (not to mention interactions) for 36 items. Such over-parameterized analyses risk spurious effects and null effects (see references in Jaeger, 2011).

In summary, while phonological differences between high and low PND words in our study are unlikely to explain our results, word-specific phonetic representations resulting from the production-perception loop might explain our results. Next, we discuss a related, though subtly different, explanation of this result.

Communicative goals and articulation

An alternative or complementary explanation of our results is provided by accounts that attribute pronunciation variation at least in part to communicative goals (e.g., Galati & Brennan, 2010; Jaeger, 2013; Lindblom, 1990; Lombard, 1911; Schertz, 2013; Stent et al., 2008; Wright, 2004; Zhao & Jurafsky, 2009). A thorough review of these and related accounts is beyond the scope of the current article (but see Jaeger & Buz, 2016). Here we focus on the basic motivation shared between communicative accounts of pronunciation variation. This basic idea is that speakers aim to be understood and as such aim to articulate words in a way that increases the expected probability of successful recognition.

Communicative accounts have been proposed, for example, to account for the phonetic reduction of repeated or otherwise contextually predictable words (Aylett & Turk, 2004, 2006) and hyper-articulation of words produced in the context of a minimally contrasting neighbor (e.g., producing pin when bin is a contextually available alternative, Buz, Jaeger, & Tanenhaus, 2014, 2015; Schertz, 2013; for discussion, see Baese-Berk & Goldrick, 2009; Goldrick et al., 2013; Kang & Guion, 2008; Seyfarth, Buz, & Jaeger, 2015). According to communicative accounts, targets will be hyper-articulated when they would be expected to be otherwise contextually confusable.

Can this argument be extended to account for effects of PND on articulation? Initial research on the relationship between PND and comprehension found that in spoken word recognition, words with greater PND had lower comprehension accuracy and slower recognition times (Luce & Pisoni, 1998; Vitevitch & Luce, 1998, 1999, though this work has been focused on English with similar studies mostly lacking for other languages). However, later work in spoken word recognition suggests that other factors, such as cohort size and viable contextual alternatives, seem to play a larger role in recognition difficulty (Creel, Aslin, & Tanenhaus, 2008; Magnuson et al., 2007). One possible reason for these findings is that PND (as measured here and in most other works) provides at best a coarse-grained approximation of the actual recognition difficulty associated with a word during incremental speech processing (for a similar point, see Gahl, 2015). For example, all standard measures of PND—including the one we have employed here—make the assumption that the addition, deletion, or substitution of any phoneme with any other phoneme all have equivalent impacts on comprehension difficulty. Data from phoneme confusion studies argue against these assumptions. Phonemes are not equally confusable with each other and the mutual confusability of phonemes can differ based on position within a syllable (e.g. Woods, Yund, & Herron, 2010; Woods, Yund, Herron, & Ua Cruadhlaoich, 2010; see also Strand, 2014).

As such, the observed effect of PND on word durations—while compatible with communicative accounts—provides at best weak evidence in favor of these accounts. We further note that parallel effects of PND on production and comprehension—while an important first step—are insufficient to establish a causal relation (see also ongoing work by Susanne Gahl). Studies that directly manipulate the perceptual confusability of words in context to see how this affects pronunciation are more promising in this regard (such as the studies cited above, Baese-Berk & Goldrick, 2009; Buz et al., 2014, 2015; Kang & Guion, 2008; Kirov & Wilson, 2012; Schertz, 2013; Seyfarth et al., 2015). With this important caveat in mind, we discuss one additional piece of evidence that the PND effects on articulation we observe in the current experiment are communicative in nature.

Revisiting vowel dispersion

Regardless of whether communicative goals affect speakers’ decisions during language production or come to affect phonetic representations through the production-perception loop, the fact that words often are used to convey intentions also might also hold an explanation for another aspect of our results: unlike previous work (Munson, 2007; Munson & Solomon, 2004), we did not find PND to affect vowel dispersion.

In this context, it interesting to revisit Munson’s studies. To avoid confounds due to comparing across vowels, Munson avoided vowel contrasts between the different conditions of the same item. Between items, however, the studies presented in Munson and Solomon (2004) and Munson (2007) contain target words that differ only in the vowels (e.g., beat - bit; put - pet - pot, bean - bone). Additionally, a few items form near-minimal pairs with regard to vowels, that—except for the vowel—differed in only one phonological feature (e.g., dot - dad; bag - beak). As a result, vowels were contrastive across items. It is possible that this caused participants to hyper-articulate vowels. This effect might be further exaggerated when the words are produced repeatedly, as was the case in both Munson and Solomon (2004, 3 repetitions of each word) and Munson (2007, 6 repetitions).

This contrasts with the current study, where vowels were never contrastive between items: within and across both items and fillers, all words differed in at least two phonological features in addition to the vowel. Additionally, our study contained no repetition of stimuli (see Table B1 in Appendix B). This difference alone is insufficient to explain why previous studies found vowel dispersion to be correlated with PND compared to the current study. One admittedly speculative explanation is that speakers engage in across-the-board increases of articulatory detail of segments that they perceived to be contrastive in the current context. This would be compatible with the lack of an effect of PND on vowel dispersion in the current study and the presence of an effect in previous work (Munson, 2007; Munson & Solomon, 2004). Although we have to leave further tests of this hypothesis to future work, research on minimal feature contrasts provides some support for this hypothesis (Baese-Berk & Goldrick, 2009; Buz et al., 2014; Kang & Guion, 2008; Kirov & Wilson, 2012; Peramunage, Blumstein, Myers, Goldrick, & Baese-Berk, 2011; Schertz, 2013). We briefly elaborate on this point.

For example, Baese-Berk and Goldrick (2009) had participants read words that began with voiceless stop consonants (/p/, /t/, /k/) to a partner who had to select what word they heard from among three alternatives. On critical trials, the voiceless onset target had its voiced minimal pair (e.g. pin and bin) visually present as an alternative. Baese-Berk and Goldrick found that speakers increased voice onset timing—one of the critical phonetic features differentiating voiced and voiceless stop consonants. In follow up work, Kirov and Wilson (2012) found that this increase in voice onset time occurred when the minimal pair differed only in the first segment and not in a different segment. Taken together this suggests that hyper-articulation may critically depend on how a target differs from contextually and lexically available alternatives.

If this explanation of our null result for vowel dispersion is along the right lines, this would mean that effects of PND on articulation are highly dependent on the specific stimuli lists employed. More generally, how hyper-articulation surfaces in a given experiment (or context) should depend on the contextually available alternatives. This is a testable prediction for future work. In the next and final section of our discussion, we return the role of PND in lexical planning.

Effects of phonological neighborhood density on lexical planning

We find that words with higher frequency-weighted PND are planned more quickly. This replicates previous studies that have investigated PND effects on speech onset latencies in the same type of population (healthy college-aged native speakers of English, e.g. Vitevitch, 2002; Vitevitch and Sommers, 2003). However, at least at first blush, our result is in conflict with some studies on other populations (e.g., native Spanish speakers, Sadat et al., 2014; Vitevitch & Stamer, 2006).

Sadat et al. (2014) present a large-scale picture naming experiment on Spanish (with 533 different target pictures) as well as trial-level reanalyses of several previously published studies on Spanish, French, and Dutch. Based on this work, Sadat and colleagues argue that there are both inhibitory and facilitatory aspects of PND on lexical planning. Specifically, Sadat and colleagues propose that “where speech production is disrupted (e.g. certain aphasic symptoms), the facilitatory component may emerge, but inhibitory processes dominate in efficient naming by healthy speakers” (Sadat et al., 2014, p. 33). This prediction is consistent with their own latency data from healthy college-aged Spanish-speaking adults (see also Vitevitch & Stamer, 2006, 2009), but conflicts with studies on English-speaking populations (Vitevitch, 2002; Vitevitch & Sommers, 2003). The prediction that healthy adults will exhibit inhibitory effects of PND is also at odds with the results obtained here (which were obtained from presumably healthy undergraduates). What then causes the apparently conflicting results? One possible explanation for the observed difference lies in methodological differences. Here, however, we focus on two more specific differences that we take to be particularly critical for future research on the role of PND in lexical planning.

One striking difference between the current study and Sadat et al. (2014) is that the current experiment investigates English, whereas Sadat and colleagues investigated Spanish speakers. It is possible that differences between the languages cause the differing results (an idea also entertained by Sadat et al., 2014, p. 47, 49–50). Consistent with this idea, we know of no study on healthy college-aged English-speaking adults that have found inhibitory effects for PND on speech onset latencies. All previous studies on this population have either found facilitatory effects (current study, Vitevitch, 2002; Vitevitch & Sommers, 2003) or null effects (Gordon & Kurczek, 2014; Munson, 2007; Newman & Bernsetin Ratner, 2007; Vitevitch, Armbrüster, & Chu, 2004). In contrast, the studies conducted by Sadat et al. (2014)—including reanalyses of additional studies on Spanish (Baus, Costa, & Carreiras, 2008; Pérez, 2007)—either returned inhibitory effects of PND on healthy college-aged Spanish-speaking adults (see also Vitevitch & Stamer, 2006) or null results. One possible explanation for this cross-linguistic difference lies in the morphological system of Spanish, compared to English (as originally proposed by Vitevitch & Stamer, 2006). Sadat et al. (2014, p. 50) propose that, due to the inflectional system of Spanish, phonologically similar words are more likely to also be meaning-related, compared to phonologically similar words in English. Since both phonological and semantic similarity can affect lexical planning (see, e.g., Chen & Mirman, 2012), this difference offers a potential explanation for the different effect of PND on lexical planning.

A second possible source for the difference between our findings and those obtained by Sadat et al. (2014) lies in the types of phonological neighbors that a word has. Research on the effects of phonological overlap between words processed in close temporal proximity suggest that it is critical which parts of words overlap phonologically (Jaeger, Furth, & Hilliard, 2012b; Meyer, 1991; O’Seaghdha & Marin, 2000; Rapp & Goldrick, 2000; Schriefers, Meyer, & Levelt, 1990; Sevald & Dell, 1994). Specifically, inhibition tends to be observed for onset overlap (e.g., cat - can), whereas facilitation tends to be observed for rhyme overlap (e.g., cat - mat; for a recent discussion of this literature, see Jaeger et al., 2012a, pp. 12–13). If this generalization is correct and the effects of phonological neighbors on lexical planning stem from the same source as the effects of phonological overlap (as also proposed in Sadat et al., 2014), this would suggest that onset density (the number of neighbors sharing the same onset as the target) should affect planning differently than, for example, rhyme density. Specifically, we would expect onset neighbors to inhibit planning, while rhyme neighbors should facilitate planning. In this context, it is interesting to consider that Sadat and colleagues found that their data was equally compatible with an inhibitory effect of onset density (Sadat et al., 2014, p. 50). Similarly, Vitevitch et al. (2004) finds that onset density has an inhibitory effect on naming latencies in English, when overall PND is controlled for. We thus consider further investigations of the effects of onset vs. rhyme density a particularly promising venue for future research (see also Sadat et al., 2014, p. 53).

Conclusions

We have examined the link between lexical planning and articulation. We find that lexical planning latencies and phonological neighborhood density have independent influences on word durations. This finding is incompatible with accounts that attribute all variation in articulation to production planning.

Although we have focused here on the role of phonological neighborhood density, our results have more general consequences for theories of the planning-articulation link. It is not uncommon in the literature to take the existence of parallel effects on planning and articulation (e.g., phonological neighborhood density affecting both speech onset latencies and word durations) as evidence that effects on articulation are mediated through effects on lexical planning (similar arguments have been applied to predictability effects Bell et al., 2009; Gahl et al., 2012; and effects of repeated mention Arnold, 2008; Bard et al., 2000). As our results illustrate, the existence of such parallel effects is, however, insufficient to establish mediation. Rather, mediation requires that effects on articulation are at least partially (partial mediation) or fully (complete mediation) explained by effects on planning. This requires analyses of the type we have conducted here that directly assess the effect of, for example, phonological neighborhood density on articulation while controlling for effects of lexical planning (and vice versa). This type of analysis in turn is best conducted at a trial-level, directly correlating measures of planning and articulation that are obtained on the same trial.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for help from the following people: Kyle Gorman, Jonathan Howell and Michael Wagner for providing us with their forced aligner; Andrew Watts, Peter Kremer, and audiences at the 2013 CUNY Sentence Processing Conference and the 2012 International Workshop on Language Production for feedback on earlier presentations of these results. We would also like to thank Susanne Gahl, Cassandra Jacobs, Sebastian Sauppe, Michael Vitevitch, and Andrew Wedel for comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript. Lastly we would like to thank Jasmin Sadat and an anonymous reviewer for initial reviews of earlier drafts of this manuscript. This work was supported by an NSF CAREER award (IIS-1150028) as well as an Alfred P. Sloan Research Fellowship to TFJ and an NRSA pre-doc (F31HD083020) to EB. The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily express the official views of these funding agencies.

Appendix A

Re-analysis of PND effects on word durations controlling for phonological differences

Here we re-analyze the effect of PND on word durations while controlling for the position in which pairs differed, the manner of articulation of contrasting segments, and voicing differences between our pairs which have been argued to affect segment and surrounding vowel durations (Crystal & House, 1986; House, 1961). Our stimuli controlled for differences in frequency, average biphone probability, phonological length, and syllable complexity and did not significantly differ in manner or voicing across high and low PND. However, our selection criteria limited our ability to fully balance position, manner, and voicing differences and thus may still account for word duration differences.

We re-conducted the word duration analyses reported in the Results section while including co-variates for the position of the contrasting segment (onset or coda), the voicing of the contrasting segment, the manner of articulation of the contrasting segment (affricate, approximant, fricative, lateral, nasal, or stop), and the interactions of position and voicing, and position and manner. Contrast position and voicing were sum-coded; manner was treatment coded with affricate as the base level.

Table A1, summarizes the results. Targets with high log-frequency-weighted PND were on average articulated with longer duration compared to targets with low PND. This difference was significant (β̂ = 0.013, t = 3.22, pχ(1)=Δ(−2Λ) < 0.01). This suggests that phonological differences in voicing and manner, and the position in which pairs differed, do not account for the effect of PND on word durations.

Table A1.

PND and phonological models for (log-transformed) word duration.

| Log duration | |

|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.082** (0.036) |

| high density word | 0.013*** (0.004) |

| contrast in coda | 0.014 (0.018) |

| segment unvoiced | 0.005 (0.007) |

| manner: approximant | −0.108*** (0.029) |

| manner: fricative | −0.091** (0.038) |

| manner: lateral | −0.072* (0.038) |

| manner: nasal | −0.075* (0.041) |

| manner: stop | −0.100*** (0.028) |

| coda: unvoiced | −0.032*** (0.005) |

| coda: approximant | −0.069*** (0.012) |

| coda: lateral | −0.073** (0.031) |

| coda: nasal | −0.048 (0.030) |

| Log Likelihood | 1,088.850 |

| Bayesian Inf. Crit. | −2,054.552 |

Note:

p<0.1;

p<0.05;

p<0.01

Appendix B

Table B1.

Stimuli used in the study including log frequency, average biphone probability, average log latency (log ms), average log duration (log ms), and average dispersion (Bark).

| Word |

Log frequency |

Avg biphone prob |

PND |

Avg log latency |

Avg log duration |

Avg dispersion |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PND group |

PND group |

PND group |

PND group |

PND group |

PND group |

PND group |

||||||||||||||

| High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | High |

Low |

High |

Low |

High |

Low |

|||||||

| Pair | mean | SE | mean | SE | mean | SE | mean | SE | mean | SE | mean | SE | ||||||||

| 1 | bark | shark | 0.74 | 1.18 | 0.0030 | 0.0027 | 22.60 | 15.12 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 2 | car | jar | 2.68 | 0.92 | 0.0046 | 0.0031 | 51.08 | 31.08 | 2.9 | 0.033 | 3.0 | 0.032 | 2.7 | 0.011 | 2.7 | 0.013 | 1.9 | 0.090 | 1.7 | 0.096 |

| 3 | bat | hat | 1.31 | 1.81 | 0.0018 | 0.0018 | 66.71 | 61.29 | 3.1 | 0.008 | 3.0 | 0.010 | 2.6 | 0.020 | 2.6 | 0.021 | 1.7 | 0.083 | 2.0 | 0.090 |

| 4 | man | pan | 3.27 | 1.09 | 0.0048 | 0.0045 | 63.43 | 55.67 | 3.0 | 0.040 | 3.0 | 0.040 | 2.7 | 0.014 | 2.7 | 0.016 | 2.0 | 0.075 | 2.2 | 0.107 |

| 5 | door | dog | 2.47 | 2.29 | 0.0042 | 0.0004 | 56.15 | 14.38 | 3.1 | 0.008 | 3.1 | 0.010 | 2.6 | 0.014 | 2.7 | 0.012 | 3.7 | 0.147 | 2.1 | 0.074 |

| 6 | fork | cork | 0.95 | 0.46 | 0.0037 | 0.0037 | 21.79 | 17.68 | 2.9 | 0.051 | 3.2 | 0.053 | 2.6 | 0.040 | 2.6 | 0.021 | 3.9 | 0.242 | 3.5 | 0.202 |

| 7 | mouse | house | 1.28 | 2.71 | 0.0003 | 0.0004 | 19.78 | 9.32 | 3.0 | 0.041 | 2.9 | 0.039 | 2.7 | 0.022 | 2.7 | 0.023 | l.5 | 0.109 | 1.9 | 0.277 |

| 8 | crown | clown | 1.14 | 1.20 | 0.0019 | 0.0015 | 9.57 | 7.24 | 3.1 | 0.016 | 3.1 | 0.008 | 2.7 | 0.019 | 2.7 | 0.020 | 1.4 | 0.100 | 1.4 | 0.090 |

| 9 | net | pet | 1.19 | 1.30 | 0.0015 | 0.0021 | 43.63 | 43.17 | 3.0 | 0.032 | 3.1 | 0.035 | 2.6 | 0.023 | 2.6 | 0.026 | 1.7 | 0.178 | l.5 | 0.165 |

| 10 | bear | hair | 1.76 | 2.19 | 0.0035 | 0.0035 | 63.83 | 59.94 | 3.1 | 0.013 | 3.2 | 0.014 | 2.6 | 0.019 | 2.7 | 0.018 | 2.0 | 0.121 | 1.9 | 0.117 |

| 11 | rain | chain | 1.69 | 1.33 | 0.0033 | 0.0014 | 57.87 | 32.53 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 12 | sock | rock | 0.95 | 1.94 | 0.0011 | 0.0018 | 39.11 | 38.34 | 3.0 | 0.008 | 3.1 | 0.012 | 2.7 | 0.013 | 2.7 | 0.013 | 1.9 | 0.064 | 2.0 | 0.085 |

| 13 | wig | Pig | 0.92 | 1.59 | 0.0022 | 0.0020 | 36.63 | 23.96 | 3.0 | 0.026 | 2.9 | 0.033 | 2.6 | 0.016 | 2.6 | 0.016 | 2.6 | 0.097 | 2.6 | 0.087 |

| 14 | ring | king | 1.97 | 2.11 | 0.0120 | 0.0089 | 39.13 | 36.10 | 3.1 | 0.010 | 3.1 | 0.008 | 2.7 | 0.017 | 2.6 | 0.014 | 2.3 | 0.091 | 2.7 | 0.111 |

| 15 | bone | bowl | 1.42 | 1.33 | 0.0010 | 0.0013 | 47.15 | 46.09 | 3.1 | 0.009 | 3.1 | 0.010 | 2.7 | 0.013 | 2.6 | 0.014 | 2.5 | 0.116 | 3.8 | 0.096 |

| 16 | road | rope | 2.05 | 1.36 | 0.0018 | 0.0017 | 42.37 | 34.89 | 3.0 | 0.028 | 2.9 | 0.029 | 2.7 | 0.017 | 2.6 | 0.015 | 2.3 | 0.167 | 3.2 | 0.229 |

| 17 | heel | wheel | 0.87 | 1.43 | 0.0010 | 0.0013 | 50.05 | 48.77 | 3.0 | 0.027 | 2.9 | 0.037 | 2.6 | 0.021 | 2.6 | 0.018 | 3.6 | 0.105 | 3.3 | 0.131 |

| 18 | book | cook | 2.25 | 1.66 | 0.0006 | 0.0004 | 29.40 | 26.50 | 2.9 | 0.034 | 3.1 | 0.029 | 2.6 | 0.019 | 2.6 | 0.018 | 2.1 | 0.216 | 1.8 | 0.295 |

| 19 | sun | gun | 1.84 | 2.33 | 0.0170 | 0.0144 | 69.82 | 54.54 | 3.0 | 0.010 | 3.1 | 0.011 | 2.7 | 0.013 | 2.6 | 0.016 | 1.4 | 0.081 | 1.1 | 0.075 |

| 20 | sink | wink | 1.23 | 0.55 | 0.0076 | 0.0067 | 23.17 | 18.11 | 3.0 | 0.030 | 3.1 | 0.021 | 2.7 | 0.027 | 2.6 | 0.021 | 2.2 | 0.229 | 2.4 | 0.156 |

Footnotes

Studies differ in how they calculate PND. Some calculate PND as the number of phonological neighbors that differ in only one segment from the target. Others sum the frequency of all neighbors (frequency-weighted PND, cf. Luce & Pisoni, 1998). Studies further differ in how edit distance is calculated (e.g., which operations of substitution, insertion, and deletion are considered) and in whether words that are morphologically related to the target are excluded when counting neighbors. We group these studies together and simply refer to their findings as PND effects.

The probability of a disfluency would be another measure of production difficulty (Shriberg, 1996). However, disfluent naming trials were rare in our experiment (5% of all trials). This left only 58 cases with disfluencies (out of 1139, prior to exclusions).

It is worth noting that recent work suggests that competition from additional neighbors only results in a net facilitation of lexical planning if the neighbors are only weakly activated (Chen & Mirman, 2012). Strongly activated neighbors, however, can result in inhibition of lexical planning. To the best of our knowledge, the predicted effect of weakly versus strongly activated neighbors on articulation has yet to be tested (though Baese-Berk & Goldrick, 2009; Kang & Guion, 2008; Kirov & Wilson, 2012; Seyfarth et al., 2015, might be taken as initial evidence in support of this prediction).

Enhanced pronunciations of high PND words compared to low PND words were also found in a number of other studies (Scarborough, 2010, 2012, 2013; Scarborough & Zellou, 2013; Wright, 2004). However, these studies were targeted at a different research question, for which they confounded PND and word frequency. Since word frequency has been shown to affect vowel duration and dispersion (Munson, 2007), we do not consider these studies further (see also a recent reanalysis of Wright (2004) by Gahl, 2015).

One source for differences between the studies could be differences in the amount of onset- vs. rhyme neighbors (see below). Other differences include the much faster speech rates in conversational speech (see Gahl et al., 2012) and the presence of context in conversational speech, which might modulate which phonological neighbors affect articulation (for related discussion, see Heller & Goldrick, 2014).

Contributor Information