Abstract

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common malignancy in males and the second most common in females worldwide. Distant metastases have a strong negative impact on the prognosis of CRC patients. The most common site of CRC metastases is the liver. Both disease progression and metastasis have been related to the patient’s peripheral blood monocyte count. We therefore performed a case-control study to assess the relationship between the preoperative peripheral blood monocyte count and colorectal liver metastases (CRLM).

Methods

Clinical data from 117 patients with colon cancer and 93 with rectal cancer who were admitted to the Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital (Beijing, China) between December 2003 and May 2015 were analysed retrospectively, with the permission of both the patients and the hospital.

Results

Preoperative peripheral blood monocyte counts, the T and N classifications of the primary tumour and its primary site differed significantly between the two groups (P < 0.001, P < 0.001, P = 0.002, P < 0.001), whereas there were no differences in the sex, age, degree of tumour differentiation or largest tumour diameter. Lymph node metastasis and a high preoperative peripheral blood monocyte count were independent risk factors for liver metastasis (OR: 2.178, 95%CI: 1.148~4.134, P = 0.017; OR: 12.422, 95%CI: 5.076~30.398, P < 0.001), although the risk was lower in patients with rectal versus colon cancer (OR: 0.078, 95%CI: 0.020~0.309, P < 0.001). Primary tumour site (P<0.001), degree of tumour differentiation (P = 0.009), T, N and M classifications, TNM staging and preoperative monocyte counts (P<0.001) were associated with the 5-year overall survival (OS) of CRC patients. A preoperative peripheral blood monocyte count > 0.505 × 109 cells/L, high T classification and liver metastasis were independent risk factors for 5-year OS (RR: 2.737, 95% CI: 1.573~ 4.764, P <0.001; RR: 2.687, 95%CI: 1.498~4.820, P = 0.001; RR: 4.928, 95%CI: 2.871~8.457, P < 0.001).

Conclusions

The demonstrated association between preoperative peripheral blood monocyte count and liver metastasis in patients with CRC recommends the former as a useful predictor of postoperative prognosis in CRC patients.

Introduction

According to the latest data from GLOBOCAN cancer statistics, colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common malignancy in males and the second most common in females, responsible for an estimated 693,900 deaths in 2012 worldwide [1]. Colorectal liver metastases (CRLM) are detected in 20–25% of patients at initial presentation but will develop in another 40–50% following primary tumour removal. The most common site for CRC metastases is the liver[2,3]. The 5-year overall survival (OS) of patients with resectable CRLM is > 40% but < 10% in those with unresectable CRLM[4]. There are currently no criteria allowing clinicians to identify the patients most likely to develop CRLM, such that approximately 90% of patients are unable to undergo curative surgery at the time of diagnosis[5]. Therefore, the identification of predictors of CRLM would be of immense benefit, enabling early treatment tailored to the individual risk of developing metastases.

Previous studies have identified a relationship between the peripheral blood monocyte count and the immune status of cancer patients. The peripheral blood monocyte count includes the number of regulatory dendritic cells (DCs), which contribute to immune suppression in cancer patients by activating and promoting the differentiation of regulatory CD4+CD25+ T cells. Thus, cancer patients with abnormally high peripheral blood monocyte counts have a poor prognosis, [6,7] and both tumour progression and metastasis have been linked to the degree of immune suppression[8]. However, the relationship between preoperative peripheral blood monocyte counts and CRLM was not clear. Therefore, in this retrospective study we analysed the clinical data of patients with CRC and CRLM to determine whether the preoperative peripheral blood monocyte count is related to the development of CRLM and/or the prognosis of patients with CRC.

Methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were (1) hospitalization at the Chinese PLA General Hospital and radical surgery performed by surgeons above deputy chief physician status; (2) diagnosis of CRC based on the postoperative pathology and the guidelines published in the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual and (3) no previous radiotherapy or chemotherapy as confirmed by medical history when obtaining preoperative peripheral blood monocyte count. Patients with acute or chronic infection, immune system diseases, or multiple primary malignancies or those who were undergoing emergency surgery were excluded. All enrolled CRC patients were staged according to the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) classification system.

Clinical data

From December 2003 to May 2015, clinical data were collected from 238 patients with CRC who underwent radical surgery and were diagnosed by postoperative pathology at the Department of Surgery, Chinese People's Liberation Army General Hospital (Beijing, China). 33 patients with initial metastatic disease were selected for operation owning preoperative imaging with resectable metastatic disease (18 patients achieved R0 resection). A final cohort of 210 patients was analyzed after the exclusion of 28 patients with missing preoperative peripheral blood monocyte count (n = 19), or missing integrated medical records (n = 6), or having immune system diseases (n = 3). The mean (±SD) age of the 137 male and 73 female patients was 56.1 (±12.9) years (range: 24–87 years). Colon cancer was diagnosed in 117 patients and rectal cancer in 93 patients. Within this group, there were 27 patients with well-differentiated, 124 with moderately differentiated and 59 with poorly differentiated cancer. The largest tumour diameter ranged from 0.8 to 18.0 cm (4.9±2.3 cm). Four patients had stage T1, 26 had stage T2, 104 stage T3 and 76 stage T4 disease. N0 was determined in 108 patients, N1 in 62 patients and N2 in 40 patients. A status of M0 was confirmed in 177 patients and M1 in 33 synchronous CRLM patients (including one with both liver and lung metastases). TNM stage 1 was diagnosed in 22 patients, stage 2 in 72 patients, stage 3 in 83 patients and stage 4 in 33 patients. The mean preoperative peripheral blood monocyte count was 0.53 (±0.21) × 109/L (range 0.14–1.98 × 109/L). Liver metastases were diagnosed based on preoperative imaging findings and postoperative pathology. Whole blood was collected into ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid containing blood collection tubes. Preoperative peripheral blood monocyte counts were performed at the clinical laboratory, Chinese People's Liberation Army General Hospital, using standard procedures on a Sysmex XS-1000i automated haematology analyser. The preoperative peripheral blood monocyte count was acquired from blood tests performed routinely before surgery. There were 127 patients received adjuvant radiochemo- or chemotherapy including: 18 TNM stage 2 patients with poorly differentiated cancer, 83 TNM stage 3 patients, 26 patients of 33 TNM stage 4 patients (5 TNM stage 4 patients could not receive adjuvant radiochemo- or chemotherapy and 2 TNM stage 4 patients refused to accept adjuvant radiochemo- or chemotherapy). Any additional information obtained from medical records. The patients were then divided according to the presence (CRLM) or absence (CRC) of liver metastasis. All patients provided written informed consent to participate in the study, which was approved by the ethics committees of the Chinese People's Liberation Army General Hospital, Beijing, China.

Follow-up

Patient follow-up was conducted by a combination of phone calls and letters. The follow-up period ended on July 1, 2015. OS was defined as the time from the completion of surgery to the follow-up date or the death of the patient. The median follow-up period was 28 months.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago IL, USA). Quantitative variables are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Measurement data with a normal distribution and homogeneity of variance were analysed for statistical differences using Student’s t test; otherwise, the Wilcoxon rank test was used. A χ2 test was used to assess differences in the numerical data and the Wilcoxon rank test for differences in relative levels. The influence of the preoperative peripheral blood monocyte count and other clinicopathological factors on the development of liver metastases from CRC was determined using multivariate logistic regression models. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were plotted to calculate the area under the ROC curve (AUC). The optimal cut-off value for the monocyte count as a prognostic indicator was calculated using the Youden index (YI). The influence of clinical and pathological factors on survival was evaluated using the Kaplan-Meier method followed by a log-rank test of the statistical differences found. A Cox regression model was used in the multivariate prognostic analysis. P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

The relationship between the clinicopathological characteristics of the patients and liver metastasis

In a univariate analysis (Table 1), there were no statistically significant differences between patients with (CRLM group) and without (CRC group) metastases with respect to sex, age, degree of tumour differentiation and the largest tumour diameter. By contrast, the preoperative peripheral blood monocyte count, T classification, N classification and primary site of the tumour significantly differed between the two groups (P < 0.05).

Table 1. Relationship between colorectal cancer liver metastases and clinicopathological characteristics.

| Clinicopathological Characteristics | Without liver metastasis n = 177 | Liver metastasis n = 33 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 55.53±12.89 | 59.21±12.63 | 0.13 |

| Gender | 0.83 | ||

| Male | 116 | 21 | |

| Female | 61 | 12 | |

| Monocyte (109/L) | 0.48±0.15 | 0.80±0.29 | <0.001 |

| Primary site | <0.001 | ||

| Colon | 88 | 29 | |

| Rectum | 89 | 4 | |

| Tumor diameter (cm) | 4.924±2.383 | 4.485±1.779 | 0.41 |

| Differentiation | 0.54 | ||

| Well | 22 | 5 | |

| Moderately | 104 | 20 | |

| Poorly | 51 | 8 | |

| T classification | 0.002 | ||

| T1 | 4 | 0 | |

| T2 | 24 | 2 | |

| T3 | 93 | 11 | |

| T4 | 56 | 20 | |

| N classification | <0.001 | ||

| N0 | 100 | 8 | |

| N1 | 50 | 12 | |

| N2 | 27 | 13 |

Logistic regression analysis of risk factors for liver metastases in CRC

Multivariate logistic regression analysis (Table 2) showed that positive lymph nodes and a high preoperative peripheral blood monocyte count were independent risk factors for liver metastasis in patients with CRC (OR: 2.178, 95%CI: 1.148~4.134, P = 0.02; OR: 12.422, 95%CI: 5.076~30.398, P < 0.001).The risk of liver metastases was significantly lower in patients with rectal cancer than in those with colon cancer (OR: 0.078, 95%CI: 0.020~0.309, P < 0.001).

Table 2. Logistic regression analysis of risk factors for liver metastases.

| Variable | B | S.E. | Wald | df | Exp(B) (95%CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N classfication N0 vs. N1/N2 | 0.778 | 0.327 | 5.670 | 1 | 2.178 (1.148–4.134) | 0.02 |

| Monocytea | 2.519 | 0.457 | 30.448 | 1 | 12.422 (5.076–30.398) | < 0.001 |

| Primary site Colon vs. Rectum | -2.550 | 0.702 | 13.179 | 1 | 0.078 (1.148–4.134) | < 0.001 |

| Constant | -6.600 | 1.497 | 19.439 | 0.001 | < 0.001 |

a Patients were divided into four groups according to the preoperative peripheral blood monocyte counts: < 0.30×109/L, 0.30< <0.50×109/L, <0.70×109/L, >0.70×109/L.

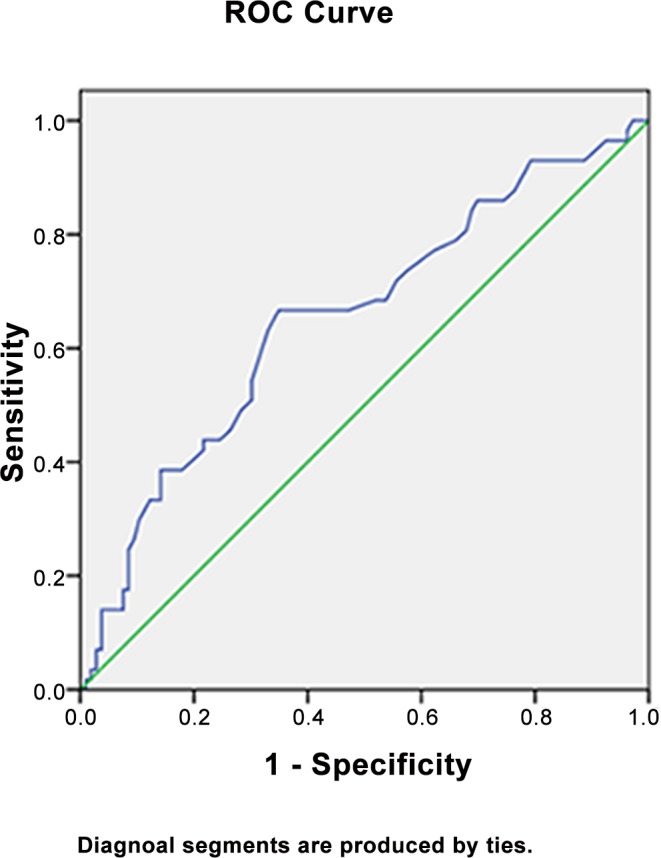

ROC curve for the optimal cut-off value and AUC

A monocyte count 0.505 ≥ 109/L, and thus a maximum YI = 0.318, resulted in an optimal cut-off value of 0.505 × 109 cells/L. The AUC was 0.653. The patients were therefore divided into those with low (< 0.505 × 109/L) and high (≥ 0.505 × 109/L) monocyte counts (Fig 1).

Fig 1. ROC curve for preoperative monocyte count.

The ROC curve for preoperative monocyte count is represented by the line chart with an AUC of 0.653 (95% CI: 0.563~0.742, P = .001).

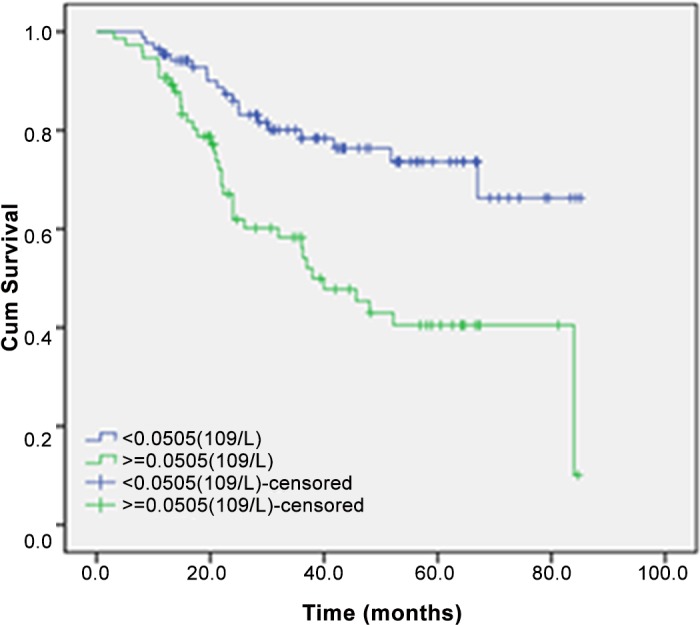

Association of the clinicopathological characteristics with 5-year OS

Univariate analyses showed that primary tumour site (P < 0.001), degree of tumour differentiation (P = 0.009), T, N and M classifications, TNM staging and preoperative peripheral blood monocyte count (P < 0.001) were associated with the 5-year OS rate (Table 3). Besides, patients with a high preoperative peripheral blood monocyte count, as defined above, had a significantly poorer 5-year OS than those with a low preoperative peripheral blood monocyte count (40.3% vs. 73.6%; P < 0.001) (Fig 2).

Table 3. Univariate analysis for prognosis in 210 patients with colorectal cancer.

| Clinicopathological Characteristics | N | 5-years OS rate(%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.12 | ||

| < 60 | 133 | 64.0 | |

| ≥ 60 | 77 | 47.3 | |

| Gender | 0.32 | ||

| Male | 137 | 62.3 | |

| Female | 73 | 44.1 | |

| Monocyte | < 0.001 | ||

| < 0.505(109/L) | 111 | 73.6 | |

| ≥ 0.505(109/L) | 99 | 40.3 | |

| Primary site | < 0.001 | ||

| Colon | 117 | 47.2 | |

| Rectum | 93 | 72.4 | |

| Size of largest tumor diameter | 0.65 | ||

| < 50mm | 108 | 53.7 | |

| ≥ 50mm | 102 | 60.9 | |

| Differentiation | 0.009 | ||

| Well | 27 | 68.3 | |

| Moderately | 124 | 61.3 | |

| Poorly | 59 | 37.0 | |

| T classification | < 0.001 | ||

| T1+T2 | 30 | 85.6 | |

| T3 | 104 | 77.2 | |

| T4 | 76 | 23.9 | |

| N classification | < 0.001 | ||

| N0 | 108 | 77.0 | |

| N1 | 62 | 52.2 | |

| N2 | 40 | 17.0 | |

| M classification | < 0.001 | ||

| M0 | 177 | 70.2 | |

| M1 | 33 | 9.3 | |

| TNM staging | < 0.001 | ||

| I | 22 | 88.9 | |

| II | 72 | 87.5 | |

| III | 83 | 52.7 | |

| IV | 33 | 9.3 |

Fig 2. OS curve grouped by preoperative monocyte count.

Patients with high preoperative monocyte count (≥ 0.505) had a significantly poorer OS than those with low preoperative monocyte count (< 0.505) (P < .001).

Multivariate analyses of prognostic factors

Using the prognostic factors from the univariate analyses and the clinically significant factors, we performed a Cox regression analysis. The preoperative peripheral blood monocyte count, primary tumour site, degree of tumour differentiation, T, N and M classifications and TNM staging were included. The results showed that the preoperative peripheral blood monocyte count (≥ 0.505 × 109/L), high T classification and liver metastasis were independent risk factors for the 5-year OS of CRC patients (RR: 2.737, 95% CI: 1.573~4.764, P < 0.001; RR: 2.687, 95%CI: 1.498~4.820, P = 0.001; RR: 4.928, 95%CI: 2.871~8.457, P < 0.001) (Table 4).

Table 4. Cox regression analysis for prognosis in 210 patients with colorectal cancer.

| Clinicopathological Characteristics | Relative risk (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Monocyte | 2.737 (1.573–4.764) | < 0.001 |

| Primary site | 0.590 (0.284–1.222) | 0.16 |

| Differentiation | 1.279 (0.793~2.064) | 0.31 |

| T classification | 2.687 (1.498~4.820) | 0.001 |

| N classification | 1.335 (0.875~2.037) | 0.18 |

| M classification | 4.928 (2.871~8.457) | < 0.001 |

| TNM staging | 2.368 (0.946~5.929) | 0.07 |

Discussion

The presence of liver metastases had a strong negative impact on the prognosis of CRC patients. Currently, there are no effective early predictors of CRLM, and the mechanism of CRLM development is unclear. The risk factors that favour CRLM have been evaluated in several studies. Hur et al. measured low expression levels of let-7i microRNA (miR) and high expression levels of miR-10b in the primary tumour tissue of CRLM patients[9]. A high level of miR-885-5p expression in serum was associated with an increased likelihood of developing CRLM [odds ratio (OR): 5.5, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.1–26.8, P = 0.03; OR: 4.9, 95% CI: 1.2–19.7, P = 0.02; OR: 3.1, 95% CI: 1.0–10.0, P = 0.05], while, the discovery was based on tissue and serum through intensive validation[9]. Wang et al. showed that the high level of serum miR-29a expression was a risk factor for liver metastases in patients with CRC[10]. Cheng et al. suggested that the increased plasma expression of miR-141 favoured metastasis and poor survival in colon cancer patients, morever, the study was conducted in two independent cohorts consisting of two different ethnic populations providing compelling evidence, while, detecting small RNA was difficult and cost highly[11]. Recent studies have demonstrated the close relationship between tumour metastasis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Several transcription factors, including zeb1, zeb2, slug, twist, snail and members of the miR-200 family, promote EMT by altering the expression of downstream genes, including β-catenin, placental cadherin (P-cad), epithelial cadherin (E-cad) and matrix metalloproteinase[12]. In the study of Chen et al., the decreased expression of E-cad contributed to CRLM[13]. Sun et al. reported that patients with colon cancer characterised by high P-cad expression were at an increased risk of developing liver metastases. The proposed mechanism was based on the suppression of E-cad expression by P-cad, which also promoted β-catenin expression[14].

The immunosuppressive environment established by the tumour allows its further growth and metastasis. A previous study showed a close relationship between the peripheral blood monocyte count, including DCs, and the immune response to the tumour[15]. In peripheral tissues, DCs exist as immature cells; their eventual maturation requires stimulation by cytokines and antigens. These activated DCs play an important role in antigen presentation and in the anti-tumour immune response of antigen-specific cytotoxic lymphocytes[16,17]. Other researchers have reported that regulatory DCs may suppress the proliferation and activation of CD4+CD25- and CD8+CD25- T cells, resulting in immune suppression and thus inhibition of an immune attack on tumour cells[7]. Wilcox et al. proposed that haematopoietic and inflammatory cytokines within the tumour microenvironment promote monocyte proliferation, which might not only drive the suppression of host anti-tumour immunity but also promote tumour angiogenesis and perhaps even tumour growth[18]. In our study, CRLM patients had a significantly higher preoperative peripheral blood monocyte count than that of CRC patients (0.80±0.29 ×109/L vs. 0.48±0.15 ×109/L, P<0.001) while, there were no statistically significant differences in sex, age, degree of tumour differentiation and the largest tumour diameter. Logistic regression analysis showed that the preoperative peripheral blood monocyte count was an independent risk factor for the development of liver metastases in CRC. There were a close relationship between CRLM and preoperative monocyte count. Taken together, these observations suggest that the high counts in CRC patients are due to an increase in regulatory DCs, leading to an immunosuppressive state that favours metastasis of the primary tumour.

There is increasing evidence of an association between the peripheral blood monocyte count and prognosis in cancer patients. Sasaki et al. retrospectively analysed the relationship between the preoperative peripheral blood monocyte count and clinicopathological factors or long-term prognosis in 198 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated by curative resection. They demonstrated a significantly worse 5-year disease-free survival in patients with a preoperative peripheral blood monocyte count > 300/mm3 (14.8%) than in those with a count ≤ 300 cells/mm3 (14.8% vs. 29.2%). A preoperative peripheral blood monocyte count > 300 cells/mm3 was identified as an independent risk factor for a disease-free survival of < 5 years[19]. Gustafson et al. examined changes in the peripheral blood of 373 patients with clear renal cell carcinoma. They found that the level of CD14+HLA-DRlo/neg monocytes in the peripheral blood of these patients correlated with the intensity of CD14 staining in tumours and adversely affected survival[20]. Marcheselli et al. analysed data from 428 patients with follicular lymphoma who were enrolled in a randomized clinical trial (FOLL05). They showed that patients with a peripheral blood absolute monocyte count (AMC) > 0.63 × 109/L had a poorer 5-year progression-free survival (PFS) than that of patients with a peripheral blood AMC ≤0.63 × 109/L (44% vs. 61%, P = 0.001)[21]. In the study of Tadmor et al. of 1450 patients with classical Hodgkinֹ’s lymphoma (cHL), those with an AMC > 750/mm3 had poorer 10-year PFS and 10-year OS than those of cHL patients with an AMC ≤ 750/mm3 (65% vs. 81%, P < 0.001 and 78% vs. 88%, P = 0.01, respectively). In a multivariate analysis, the AMC was determined to be of prognostic significance for PFS [hazard ratio (HR), 1.54, P = 0.006] and OS in patients with nodular sclerosis diagnosed by histology (HR, 1.54, P = 0.006; HR, 1.56; P = 0.04) [22]. In the present study, 5-year OS was significantly poorer in patients with a high (≥ 0.505 × 109/L) versus low (< 0.505 × 109/L) preoperative peripheral blood monocyte count. In fact, a preoperative peripheral blood monocyte count (≥ 0.505 × 109/L) was identified as an independent risk factor for 5-year OS in CRC patients. An elevated preoperative peripheral blood monocyte count might reflect a high degree of immune suppression and high levels of inflammatory cytokines. The latter are important in many cellular processes, including the development of malignancies, and thus may further augment the inflammatory response[23]. Immune suppression together with the nonspecific inflammatory response could have a negative impact on the 5-year OS of CRC patients.

In conclusion, our study was able to demonstrate an association between the preoperative peripheral blood monocyte count and the presence of liver metastasis in patients with CRC. Thus, the preoperative peripheral blood monocyte count may be an inexpensive and feasible approach to predict the postoperative prognosis of these patients. However, the limitations of this study were the single-centre retrospective design and the small sample size. Larger prospective studies are needed to confirm our results and to identify the exact mechanisms linking an increase in the preoperative peripheral blood monocyte count with CRLM before it can be used as a prognostic indicator in CRC patients.

Supporting Information

(DOCX)

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof. Xinyuan Tong for assistance with the statistical analyses. All of the authors offered critical comments on the manuscript and participated in its revision.

Abbreviations

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- CRLM

colorectal liver metastases

- DCs

dendritic cells

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- AUC

area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

- YI

Youden index

- EMT

epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- CRCC

clear renal cell carcinoma

- FL

follicular lymphoma

- PFS

progression-free survival

- OS

overall survival

- cHL

classical Hodgkin Lymphoma

- AMC

absolute monocyte count

- CI

confidence interval

- HR

hazard ratio

- OR

odds ratio

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 61170123) (URL: http://www.nsfc.gov.cn/).

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87–108. Epub 2015/02/06. 10.3322/caac.21262 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kemeny NE. Treatment of metastatic colon cancer: "the times they are A-changing". J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(16):1913–6. 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.4500 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmoll HJ, Van Cutsem E, Stein A, Valentini V, Glimelius B, Haustermans K, et al. ESMO Consensus Guidelines for management of patients with colon and rectal cancer. a personalized approach to clinical decision making. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(10):2479–516. 10.1093/annonc/mds236 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ye LC, Liu TS, Ren L, Wei Y, Zhu DX, Zai SY, et al. Randomized controlled trial of cetuximab plus chemotherapy for patients with KRAS wild-type unresectable colorectal liver-limited metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(16):1931–8. 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.8308 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adam R, Vinet E. Regional treatment of metastasis: surgery of colorectal liver metastases. Ann Oncol. 2004;15 Suppl 4:iv103–6. 10.1093/annonc/mdh912 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen MH, Chang PM, Chen PM, Tzeng CH, Chu PY, Chang SY, et al. Prognostic significance of a pretreatment hematologic profile in patients with head and neck cancer. Journal of cancer research and clinical oncology. 2009;135(12):1783–90. Epub 2009/06/25. 10.1007/s00432-009-0625-1 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takahashi T, Kuniyasu Y, Toda M, Sakaguchi N, Itoh M, Iwata M, et al. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by CD25+CD4+ naturally anergic and suppressive T cells: induction of autoimmune disease by breaking their anergic/suppressive state. Int Immunol. 1998;10(12):1969–80. Epub 1999/01/14. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heeren AM, Kenter GG, Jordanova ES, de Gruijl TD. CD14 macrophage-like cells as the linchpin of cervical cancer perpetrated immune suppression and early metastatic spread: A new therapeutic lead? Oncoimmunology. 2015;4(6):e1009296 Epub 2015/07/15. 10.1080/2162402x.2015.1009296 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc4485785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hur K, Toiyama Y, Schetter AJ, Okugawa Y, Harris CC, Boland CR, et al. Identification of a metastasis-specific MicroRNA signature in human colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(3). Epub 2015/02/11. 10.1093/jnci/dju492 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc4334826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang LG, Gu J. Serum microRNA-29a is a promising novel marker for early detection of colorectal liver metastasis. Cancer Epidemiol. 2012;36(1):e61–7. Epub 2011/10/25. 10.1016/j.canep.2011.05.002 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng H, Zhang L, Cogdell DE, Zheng H, Schetter AJ, Nykter M, et al. Circulating plasma MiR-141 is a novel biomarker for metastatic colon cancer and predicts poor prognosis. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e17745 Epub 2011/03/30. 10.1371/journal.pone.0017745 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc3060165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RY, Nieto MA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009;139(5):871–90. Epub 2009/12/01. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.007 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen X, Wang Y, Xia H, Wang Q, Jiang X, Lin Z, et al. Loss of E-cadherin promotes the growth, invasion and drug resistance of colorectal cancer cells and is associated with liver metastasis. Molecular biology reports. 2012;39(6):6707–14. Epub 2012/02/09. 10.1007/s11033-012-1494-2 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun L, Hu H, Peng L, Zhou Z, Zhao X, Pan J, et al. P-cadherin promotes liver metastasis and is associated with poor prognosis in colon cancer. The American journal of pathology. 2011;179(1):380–90. Epub 2011/06/28. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.03.046 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc3123784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ganti SN, Albershardt TC, Iritani BM, Ruddell A. Regulatory B cells preferentially accumulate in tumor-draining lymph nodes and promote tumor growth. Sci Rep. 2015;5:12255 Epub 2015/07/21. 10.1038/srep12255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steinman RM. The dendritic cell system and its role in immunogenicity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1991;9:271–96. Epub 1991/01/01. 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.001415 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bie Y, Xu Q, Zhang Z. Isolation of dendritic cells from umbilical cord blood using magnetic activated cell sorting or adherence. Oncol Lett. 2015;10(1):67–70. Epub 2015/07/15. 10.3892/ol.2015.3198 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc4487079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilcox RA, Ristow K, Habermann TM, Inwards DJ, Micallef IN, Johnston PB, et al. The absolute monocyte count is associated with overall survival in patients newly diagnosed with follicular lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53(4):575–80. Epub 2011/11/22. 10.3109/10428194.2011.637211 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sasaki A, Iwashita Y, Shibata K, Matsumoto T, Ohta M, Kitano S. Prognostic value of preoperative peripheral blood monocyte count in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Surgery. 2006;139(6):755–64. Epub 2006/06/20. 10.1016/j.surg.2005.10.009 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gustafson MP, Lin Y, Bleeker JS, Warad D, Tollefson MK, Crispen PL, et al. Intratumoral CD14+ Cells and Circulating CD14+HLA-DRlo/neg Monocytes Correlate with Decreased Survival in Patients with Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2015. Epub 2015/05/23. 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-15-0260 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marcheselli L, Bari A, Anastasia A, Botto B, Puccini B, Dondi A, et al. Prognostic roles of absolute monocyte and absolute lymphocyte counts in patients with advanced-stage follicular lymphoma in the rituximab era: an analysis from the FOLL05 trial of the Fondazione Italiana Linfomi. Br J Haematol. 2015;169(4):544–51. Epub 2015/03/31. 10.1111/bjh.13332 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tadmor T, Bari A, Marcheselli L, Sacchi S, Aviv A, Baldini L, et al. Absolute Monocyte Count and Lymphocyte-Monocyte Ratio Predict Outcome in Nodular Sclerosis Hodgkin Lymphoma: Evaluation Based on Data From 1450 Patients. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(6):756–64. Epub 2015/06/06. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.03.025 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao W, Li J, Zhang Y, Gao P, Zhang J, Guo F, et al. Screening and identification of apolipoprotein A-I as a potential hepatoblastoma biomarker in children, excluding inflammatory factors. Oncol Lett. 2015;10(1):233–9. Epub 2015/07/15. 10.3892/ol.2015.3207 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc4487141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.