Abstract

Linguatula serrata, one of the parasitic zoonoses, inhabits the canid and felid respiratory system. The parasite is tongue-shaped, lightly convex dorsally and flattened ventrally. Males measure 1.8–2 cm, while females measure 8–13 cm in length. Disease due to infection with this parasite in humans is more likely to cause pharyngitis, nausea and vomiting, sore and itchy throat, cough, phlegm and runny nose. Present study aimed to determine linguatula’s larva somatic antigens in lymph nodes of infected goats and also reveal the major component of antigenic protein. To determine the electrophoretic pattern of L. serrata’s larvae, 50 samples were taken from goat’s referred to the slaughter house of Amol, Mazandaran, Iran. After performing SDS-PAGE on somatic antigens, 6 bands (19, 20, 36, 48, 75,100 KDa) were seen in which the 36, 48 and 75 KDa bands were more prominent. In conclusion, it is recommended to determine the most important antigenic protein of this parasite could be used an experimental model in infection up to determine the most significant component of this parasite’s antigen and use of that in immunogenicity and detection of infection.

Keywords: Linguatula serrata, Protein, SDS-PAGE, Goat, Iran

Introduction

Linguatula serrata, one of the parasitic zoonoses, inhabits the canid and felid respiratory system (final hosts). The eggs are expelled from the respiratory passages of the final host and, when swallowed by a suitable herbivorous animal (intermediate host), the larva reaches the mesenteric lymph nodes, liver, lung, etc. in which it develops to the infective nymphal stage after six to nine moulting. It usually lies in a small cyst surrounded by a viscid turbid fluid. The final host becomes infected by eating the infected viscera (Anaraki Mohammadi et al. 2008). The parasite is tongue-shaped, lightly convex dorsally and flattened ventrally. Males measure 1.8–2 cm, while females measure 8–13 cm in length (Bahrami et al. 2011). Humans may be infected with linguatula either by ingestion of nymphs of L. serrata resulting in a condition called nasopharyngeal linguatulosis or Halzoun syndrome or by ingestion of infective eggs which develop in internal organs resulting in visceral linguatulosis (Dincer 1992). Human infection via consumption of raw or under-cooked liver and lymph nodes has been reported from Africa, South-East Asia and the Middle East (Koehsler et al. 2011). The clinical signs of Halzoun syndrome include pharyngitis, salivation, dysphagia and coughing. In the case of visceral linguatulosis, the infection generally remains asymptomatic (Koehsler et al. 2011).

Disease due to infection with this parasite in humans is more likely to cause pharyngitis, nausea and vomiting, sore and itchy throat, cough, phlegm and runny nose (Koehsler et al. 2011). Diagnosis in final host will be done by clinical signs and separating of the parasite eggs in feces, nasal secretions and animal’s saliva. The diagnosis in intermediate hosts will be done by biopsy (Rasouli et al. 2011).

Several studies have been conducted on the prevalence rate of L. serrata in Iran in dogs (Rasouli et al. 2011), camels (Gharedaghi et al. 2010), buffaloes (Sivakumar et al. 2005; Nematollahi et al. 2005), sheep (Gharedaghi et al. 2010; Kafi Ahmadi et al. 2005) and goats (Nourollahi Fard et al. 2010; Razavi et al. 2004; Tavassoli et al. 2007; Youssefi et al. 2012). Due to broad prevalence and distribution of L. serrata in Iran, present study aimed to determine linguatula’s larva somatic antigens in lymph nodes of infected goats and also reveal the major component of antigenic protein.

Materials and methods

Preparation of the samples

To determine the electrophoretic pattern of L. serrata’s larvae, 50 samples were taken from goats referred to the slaughter house of Amol city, Amol, Mazandaran, Iran. For each case 10 cc of blood were taken from the jugular vein of goats and after slaughter five mesenteric lymph nodes was isolated from carcasses and all samples were transferred to the Laboratory of Veterinary parasitology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Islamic Azad University, Babol branch. In laboratory the lymph nodes were cut and incubated in PBS for 30 min, after this period of time the lymph nodes were removed and contents of plate were examined under a stereoscope. Positive samples were identified and larvae were collected in a sterile container and washed for three times by PBS. Blood samples were centrifuged at 2,000g for 5 min, afterward; the sera were recovered and stored in −70 °C. The larvae were sonicated on ice with ultrasonicator (Hielscher, Germany). By using a refrigerator centrifuge (Ependorf, Germany), the sonication contents were centrifuged for 10 min at 5,000g at 4 °C. Then, the supernatant was collected and protein assay was done by the Bradford method.

SDS-PAGE

The prepared antigens were run on SDS–polyacrylamide gels, composed of 4 % resolving gel and 10 % stacking gel, under reducing conditions using the discontinuous buffer system. For size estimation in SDS-PAGE, a pre-stained protein marker at a range of 11-180KDa molecular weight (PS10 plus) was used.

Results

The study was conducted on slaughtered goats of Amol city, Mazandaran province in 1392. During this study, 50 goats of mixed gender were studied, that 35 (70 %) were female and 15 (30 %) were male. From 50 goats, 20 goats were L. serrata positive that 13 (65 %) of them were female and 7 (35 %) of them were male.

Protein assay

After the protein assay, by Bradford method, the somatic antigens protein measured was 220 nanograms per milliliter in volume unit.

SDS-PAGE

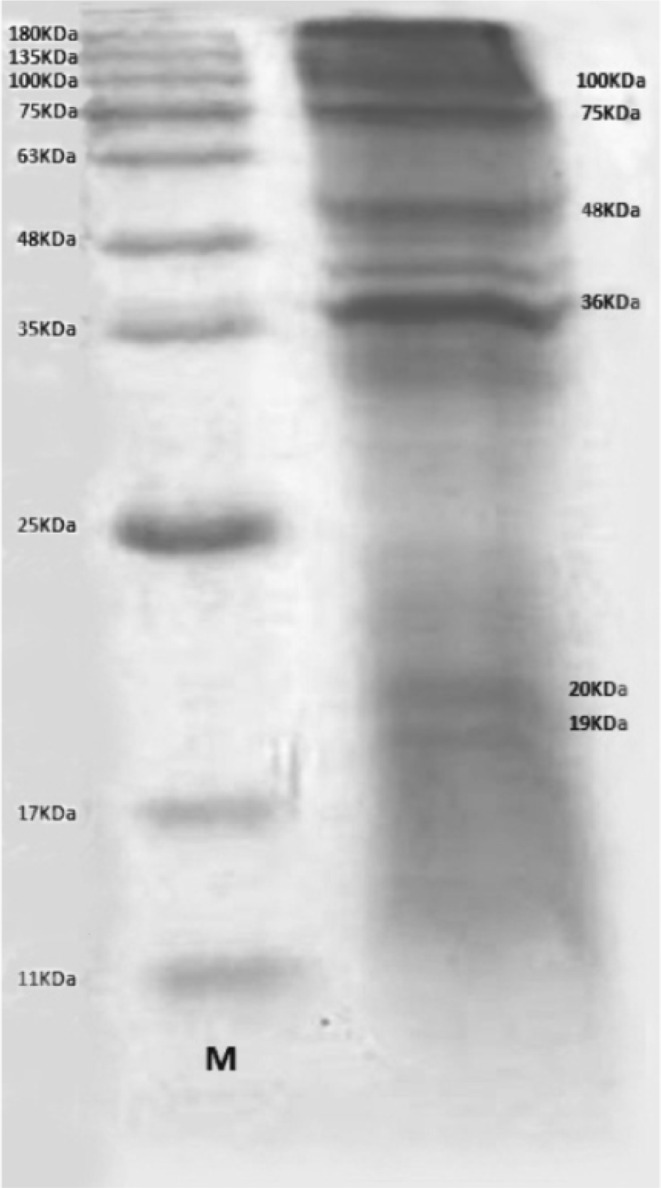

After performing SDS-PAGE on somatic antigens, 6 bands (19, 20, 36, 48, 75,100 KDa) were seen in which the 36, 48 and 75 KDa bands were more prominent (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Protein bands recovered from Linguatula serrata’s larva (right) and marker (left)

Discussion

The prevalence of Linguatulosis is important in ruminants because without any specific clinical symptoms, it leads to reduction of animal productions and hidden economic loss, as well as public health hazards. There are several reports of contamination to L. serrata’s nymph in ruminants and infection to adult forms of this parasite in dogs and human from all around the world (Nematollahi et al. 2005). The prevalence of linguatulosis in goats has been reported from different regions in Iran and other countries (Razavi et al. 2004; Yakhchali et al. 2009). For example, Nourollahi Fard et al. (2010) reported L. serrata infection in 49.1 % of examined goats in Kerman, Iran. Razavi et al. (2004) and Tavassoli reported the infection rate of the goats slaughtered at a slaughterhouse in Shiraz and Urmia, as 29.9 and 68 %, respectively (Tavassoli et al. 2007). Dincer reported that 37 % of examined slaughtered goats in Turkey were diagnosed to be infected by L. serrata (Dincer 1992). Rezaei reported that 409 out of 770 (55.27 %) goats were infected with nymph stages of L. serrata (Razavi et al. 2004). Furthermore, Youssefi reported among 107 goats, 73 (68 %) were infected with L. serrata larvae (Youssefi et al. 2012). L. serrata nymphs in the current study were less (40 %). At present study 7 out of 15 males (35 %) and 13 out of 35 females (65 %) were found to be infected and Rezaei also reported 138 out of 305 males (45.24 %) and 271 out of 435 females (62.29 %) were found to be infected. The prevalence of L. serrata nymphs in females was significantly greater than that of males. The cause of this difference may have been due to the higher mean age of females than that of males (Razavi et al. 2004). In the present study, in electrophoresis of L. serrata larvae’s antigens, six bands (19, 20, 36, 48, 75,100 KDa) were seen on somatic antigens in which the 36, 48 and 75 KDa bands were more prominent. In the study conducted by Jones and Riley, on L. serrata larvae using Western blotting method, they revealed that only two protein bands were more prominent, the 48 and 150 KDa. In conclusion, it is recommended to determine the most important antigenic protein of this parasite could be used an experimental model in infection up to determine the most significant component of this parasite’s antigen and use of that in immunogenicity and detection of infection (Jones and Riley 1991).

References

- Anaraki Mohammadi G, Mobedi I, Ariaiepour M, Pourmohammadi Z. Iran and characterization of the isolated Linguatula serrata. Iran J Parasitol. 2008;3(1):53–55. [Google Scholar]

- Bahrami AM, Yousefizadeh SH, Kermanjani A. The contamination of infestation to Linguatula serrata in stray dogs and cattle in Ilam. J Ilam Univ Med Sci. 2011;19(2):60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Dincer S. Prevalence of L. serrata in stray dogs and animal slaughtered at Yurkey. Vet Fak Derg Ankara Univ. 1992;29:324–330. [Google Scholar]

- Jones DA, Riley J. An ELISA for the detection of pentatomid infections in the rat. Parasitilogy. 1991;3:331–337. doi: 10.1017/S0031182000059849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabirian Gharedaghi Y, Bajestani A, Changizi N. Report infectivity camel to Linguatula serrata’s nymph Khorasan Razavi Province. J Vet Med. 2010;4(4):87–90. [Google Scholar]

- Kafi Ahmadi A, Dalirnaghadeh B, Tavassoli M. Use of allergic skin test in the diagnosis of mesenteric lymph nodes infected sheep to Linguatula serrata’s nymph. J Vet Fac Tehran Univ. 2005;60(4):375–378. [Google Scholar]

- Koehsler M, Walochnik J, Georgopoulos M, Pruente C, Boeckeler W, Auer H, Barisani T. Linguatula serrata tongue worm in human eye, Austria. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17(5):870–872. doi: 10.3201/eid1705.100790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nematollahi A, Karimi H, Niazpour F. Prevalence of infection and histopathological lesions of liver and lung at slaughter cattle in slaughterhouse of East Azerbaijan province for the infection of Linguatula serrata nymphs in different seasons. J Vet Med Tehran Univ. 2005;60(2):161–165. [Google Scholar]

- Nourollahi Fard SR, Kheirandish R, Asl EN, Fathi S. The prevalence of Linguatula serrata nymphs in goats slaughtered in Kerman slaughterhouse, Kerman, Iran. Vet Parasitol. 2010;171:176–178. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasouli S, Amniat Talab A, Sedghian M, Haji Karimlo B, Azizpour Sarijeh A, Jafari K. Prevalence of mature Linguatula serrata in stray dogs in the city of Urmia. J Vet Med. 2010;4(1):765–771. [Google Scholar]

- Ravindran R, Lakshmanan B, Ravishankar C, Subramanian H. Prevalence of Linguatula serrata in domestic ruminants in south India. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2008;39(5):808–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razavi SM, Shekarforoush SS, Izadi M. Prevalence of Linguatula serrata nymphs in goats in Shiraz, Iran. Small Rumin Res. 2004;54(3):213–217. doi: 10.1016/j.smallrumres.2003.11.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sivakumar P, Sankar M, Nambi PA, Praveena PE, Singh N. The occurrence of nymphal stage of Linguatula serrata in water buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis). Nymphal morphometry and lymph node pathology. J Physiol Pathol Clin Med. 2005;52:506–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0442.2005.00774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajik H, Tavassoli M, Dalirnaghadeh B, Danehloipour M. Mesenteric lymph nodes infection with Linguatula serrata nymphs in cattle. Iran J Vet Res Univ Shiraz. 2006;7(4):82–85. [Google Scholar]

- Tavassoli M, Tajik H, Dalirnaghadeh B, Lotfi H. Contamination of mesenteric lymph nodes to Linguatula serrata in Uramia slaughter. Iran J Vet Med. 2007;3(3):85–89. [Google Scholar]

- Yakhchali MA, Hji Mohammadi B, Raeisi M. The prevalence of Linguatula serrata in slaughtered ruminants in the city of Urmia slaughterhouse. J Vet Res. 2009;4(4):322–329. [Google Scholar]

- Youssefi MR, Fallah Omrani V, Alizadeh A, Moradbeigi M, Darvishi MM, Rahimi MT. The prevalence of Linguatula serrata nymph in mesenteric lymph nodes of domestic ruminants in Iran, 2011. World J Zool. 2012;7(3):171–173. [Google Scholar]