Abstract

The complex information-processing capabilities of the central nervous system emerge from intricate patterns of synaptic input-output relationships among various neuronal circuit components. Understanding these capabilities thus requires a precise description of the individual synapses that comprise neural networks. Recent advances in fluorescent protein engineering, along with developments in light-favoring tissue clearing and optical imaging techniques, have rendered light microscopy (LM) a potent candidate for large-scale analyses of synapses, their properties, and their connectivity. Optically imaging newly engineered fluorescent proteins (FPs) tagged to synaptic proteins or microstructures enables the efficient, fine-resolution illumination of synaptic anatomy and function in large neural circuits. Here we review the latest progress in fluorescent protein-based molecular tools for imaging individual synapses and synaptic connectivity. We also identify associated technologies in gene delivery, tissue processing, and computational image analysis that will play a crucial role in bridging the gap between synapse- and system-level neuroscience.

Keywords: fluorescent protein sensors, synaptic connectivity, synapses, gene delivery, mapping and localization, light microscopy

Introduction

The synapse is the primary site for neurons to make functional contacts for exchanging information. The term “synapse”, meaning conjunction in Greek (synapsis = together + to fasten), was coined in 1897 by the eminent physiologist Charles Scott Sherrington (Nobel Laureate 1932). But the idea that synapses play critical roles as dynamically polarized, communication contacts was proposed by Santiago Ramon y Cajal (Nobel Laureate 1906). Since then, the synapse as a structural and functional communication unit has been in the spotlight of neuroscientific inquiry (Cowan et al., 2001). In fact, many studies have demonstrated that synaptic events, such as changes in molecular composition, structure, efficacy, and potentiation, play important roles in brain functions including memory formation, perception, and other complex behaviors (Tsien et al., 1996; Markram et al., 1997; Malinow and Malenka, 2002; Russo et al., 2010; Caroni et al., 2014). An important focus has been to visualize the synapse and to measure its activity. In 1954, DeRobertis and Palay first observed synapses independently by electron microscopy (EM) and George Gray suggested there may be different types of synapses, i.e., excitatory and inhibitory (De Robertis and Bennett, 1955; Palay and Palade, 1955; Palay, 1956; Gray, 1959). EM provides enough resolution for nanometer-scale imaging of the synaptic ultrastructure, something that cannot be achieved by light microscopy (LM) because of its diffraction limit. However, despite recent advances that have reduced the time needed for image acquisition and reconstruction, EM remains inherently time-consuming, labor-intensive, and volume-limited for large neural circuits.

With the recent engineering of fluorescent proteins (FPs) and new developments in light-favoring tissue clearing and advanced optical methods, LM is rising as a potent alternative tool for investigating individual synapses in the context of neural networks (Gray, 1959; Keller et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2012; Tomer et al., 2012; Chung et al., 2013; Richardson and Lichtman, 2015). Imaging the synapse with LM by using newly engineered FPs tagged to synaptic proteins or targeted to synaptic structures enables fine-resolution illumination of synaptic anatomy and function in large neural circuits, possibly in real-time. In this review, we describe recent FP-based molecular tools for imaging individual synapses and synaptic connectivity in the contexts of single- and dual component synaptic detection. We also identify crucial technologies: gene delivery of molecular synapse detector; tissue clearing for whole-brain imaging; and computational analysis, whose parallel development has potential to bridge synaptic sensor engineering and systems neuroscience. We end by proposing a scheme of technological integration for synaptic neuroscience at the systems level.

Single Component Synaptic Detection

The discovery of green fluorescent protein (GFP) and its derivatives revolutionized the visualization of biological phenomena, including the individual synapse and its functions. GFP and other FPs are relatively inert and small (27 kDa) and can be used to tag synaptic proteins while minimally interfering with their normal functions. In fact, the distribution, trafficking, and physiological changes of synaptic proteins caused by neural activity became evident in the last two decades, largely through observations of synaptic proteins, such as synaptophysin (Li and Murthy, 2001) vesicle-associated membrane protein 2 (VAMP2; Ahmari et al., 2000), postsynaptic density protein-95 (PSD-95; Nelson et al., 2013) calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CaMKII; Shen et al., 2000), α-amino-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor (AMPAR; Zamanillo et al., 1999) and so forth, that had been tagged with FPs. Recently, sophisticated molecular engineering has allowed even more precise and detailed visualization of synaptic structure, composition, and physiology (Chen et al., 2014; Fortin et al., 2014; Figure 1, Table 1).

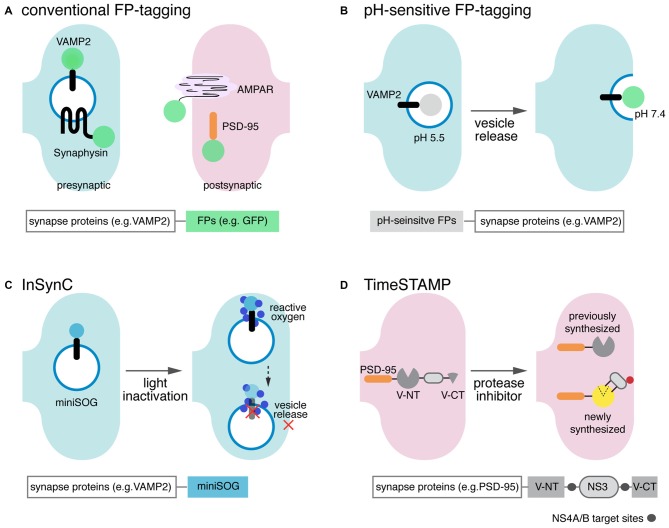

Figure 1.

Scheme of single component synapse detectors. (A) Graphical depiction of the conventional green fluorescent protein (GFP) tagging scheme and summary of the expressed carrier-sensor construct. GFP (green circle) and other fluorescent proteins (FPs) are directly tagged to synaptic proteins in the presynaptic terminal or postsynaptic spines. Major targets for tagging include presynaptic vesicle proteins (e.g., vesicle-associated membrane protein 2 (VAMP2) and synaptophysin), postsynaptic receptors (e.g., α-amino-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor, AMPAR) and postsynaptic density protein-95 (PSD-95). (B) pH-sensitive FP mutants are fused to synaptic vesicle membrane proteins, such as VAMP2, to visualize vesicle secretion/recycling and neurotransmission. A pH-sensitive GFP variant, pHluorin does not fluoresce (gray circle) when inside the acidic chemical environment of the synaptic vesicle, but becomes highly fluorescent (green circle) when the vesicle is released and exposed to the neutral extracellular environment. (C) Inhibition of Synaptic Release with CALI (InSynC): attached to target SNARE proteins, molecular actuators such as mini small singlet oxygen generator (miniSOG; light blue filled-in circle) selectively inactivate specific synaptic proteins that regulate vesicle release and other synaptic events. When illuminated with blue light, miniSOG stimulates generation of reactive oxygen species (small, dark blue filled-in circles), which then oxidizes susceptible amino acid residues in target vesicle proteins and deactivates protein functions. (D) TimeSTAMP effectively tracks spatiotemporally controlled protein synthesis and trafficking in living neurons. In the presence of a membrane-permeable protease inhibitor, NS3 protease (gray oval) activity is inhibited, and Venus C-terminus (Venus CT) and Venus N-terminus (Venus NT) reconstitute as fluorescent Venus (yellow circle). Reconstituted Venus accumulates in the postsynaptic spine, the trafficking destination of the fused PSD-95. When the protease inhibitor is present, however, NS3 protease cleaves the protease target sites (gray circles flanking NS3), preventing Venus reconstitution.

Table 1.

Summarized methods of single and dual component synapse detection.

| Single component | Dual component | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synaptic release-detecting FPs | InSynC | TimeSTAMP | GRASP | mGRASP | Syb:GRASP XRASP | SynView | ID-PRIME | |

| Detection/working module | pH-sensitive FPs: pHluorin, pHTomato | miniSOG-generated reactive oxygen | Reconstitution of VenusNT and VenusCT | Reconstitution of spGFP1-10 and spGFP11 | Reconstitution of spGFP1-10 and spGFP11 | Reconstitution of spXFP1-10 and spXFP11 | Reconstitution of spGFP1-10 and spGFP11 | Enzymatic interaction of LpIA and LAP |

| Synaptic targeting module | Synaptophysin, VAMP2, PSD-95, CaMKII, vGLUT1, mGluRs | Synaptophysin, VAMP2 | PSD-95, CaMKII, Neuroligin | Human CD4, PTP-3A, nlg-1 | Rat neurexin1-β, mouse neuroligin-1 | Synaptobrevin, human CD4 | Rat neurexin-1β, rat neuroligin-1, 2 | Human neurexin-3β, mouse neurexin-1β, rat neuroligin-1 |

| Model Systems | ||||||||

| In vitro | HEK, primary cultured neurons, organotypic slices | Primary cultured neurons, organotypic slices | HEK, primary cultured neurons | N/A | N/A | HEK | HEK, COS-7, primary cultured neurons | HEK, primary cultured neurons |

| In vivo | N/A | N/A | N/A | C.elegans, Drosophila | Mouse | Drosophila | N/A | N/A |

| Remarks | Tracking of presynaptic vesicle release, postsynaptic receptor trafficking | Optically inhibiting synaptic release with good spatial resolution | Optical pulse-chase labeling of synaptic proteins with high spatiotemporal resolution | in vivo synaptic detection in invertebrate circuits | in vivo synaptic detection in vertebrate circuits | Activity-dependent labeling of multiple synaptic inputs | Synapse labeling by direct interaction of neurexin-neuroligin | Enzyme-based visualization of direct interaction of neurexin-neuroligin |

| Lacks in vivo application with quantitative analysis | Lacks physiologically relevant temporal resolutions due to slow recovery | Awaits mammalian in vivo application | Limited to apply mammalian system | Limited to detect functional synaptic connections | Limited to apply mammalian system, limited temporal resolutions | Lacks in vivo verification and application | Requires separate introduction of exogenous ligase and antibody-fluorophore conjugates | |

| References | Miesenböck et al. (1998), Sankaranarayanan and Ryan (2000), Kopec et al. (2006), Voglmaier et al. (2006) and Li and Tsien (2012) | Lin et al. (2013) | Lin et al. (2008) and Butko et al. (2012) | Feinberg et al. (2008), Gordon and Scott (2009), Gong et al. (2010), Park et al. (2011), Yuan et al. (2011), Fan et al. (2013), Pech et al. (2013) and Gorostiza et al. (2014) | Feng et al. (2012), Kim et al. (2012) and Druckmann et al. (2014) | Karuppudurai et al. (2014), Frank et al. (2015), Macpherson et al. (2015) and Li et al. (2016) | Tsetsenis et al. (2014) | Liu et al. (2013) |

pH-Sensitive FPs for Visualizing Vesicle Release: pHluorin, pHTomato, and pHuji

Although previous, straightforward, FP-based detection of synaptic distribution revealed many important details of synaptic physiology, synaptic vesicle release/recycling and neural activity-driven changes in membrane-bound synaptic proteins are difficult to be detected by regular FP-tagging. Special sensors of vesicle secretion and neurotransmission have been developed by linking vesicle membrane proteins with pH-sensitive mutants of GFP called pHlourin (Miesenböck et al., 1998). The fluorescence intensity of pHluorin largely depends on the pH of its biochemical environment: in acidic environments with pH below 6.5, pHluorin is mostly nonfluorescent in 480 nm of light illumination, but becomes highly fluorescent in neutral environments with pH around 7.4. This special feature of pHluorin was achieved by several mutations on residues important for the proton-relay of tyrosine 66 in the chromophore (S147D, N149Q, T161I, S202F, and Q204T). These amino acid substitutions, which set the pKa of pHluorin to around 7.0, can facilitate the pH-dependent switching of the electrostatic environment of the chromophore, allowing the pH-dependent changes in fluorescent intensity (Sankaranarayanan and Ryan, 2000). When pHluorin is fused to presynaptic vesicle proteins such as VAMP2 (Miesenböck et al., 1998), synaptophysin (Zhu et al., 2009), and vesicular glutamate transporter (vGluT; Voglmaier et al., 2006), the release and recycle of synaptic vesicles can be monitored as the pH inside the synaptic vesicles (~5.5) transitions to the pH of the extracellular environment (~7.4). Thus, by tracking changes in pHluorin fluorescence intensity, one can detect real-time presynaptic exocytosis in living, active neurons. Similarly, postsynaptic endo-/exo-cytosis and related receptor dynamics can be visualized by pHluorin-fused mGluRs, for instance (Pelkey et al., 2007).

More recently, red pH-sensitive FPs such as pHTomato (Li and Tsien, 2012) and pHuji (Shen et al., 2014) have been developed, allowing for the simultaneous monitoring of multiple synaptic activities when combined with the green GFP-based sensors (e.g., GCaMP). pHTomato (pKa ~ 7.8) was derived from mStrawberry by introducing six mutations (F41T, F83L, S182K, I194K, V195T, and G196D). Synaptophysin-fused pHTomato (sypHTomato) has been shown to be suitable for simultaneously monitoring the fusion of synaptic vesicles and, when paired with GCaMP3, postsynaptic Ca2+ changes in living neurons. In addition, multiple synaptic events have been successfully measured by using sophisticated combinations of these pH-sensitive FP-fused synaptic proteins and spectrally distinct variants of optogentic stimulators (ChR2-T2A-vGluT-pHlourin and VChR1-T2A-synpHTomato). However, the pH-sensitivity of pHTomato is relatively low (3-fold change in pH 5.5–7.5). Thus, a new red pH-sensitive FP, named pHuji, has been more recently derived from mApple (Shaner et al., 2008) by including a K163Y mutation, resulting in high pH sensitivity (20-fold change in pH 5.5–7.5). The use of different colored pH-sensitive FPs together with a Ca2+ indicator and/or a spectrally distinct optogenetic modulator offers a new promising readout system for complex, coordinated synaptic events.

Inhibition of Synaptic Release with CALI (InSynC)

Beyond merely visualizing the distributions and endo-/exocytosis of synaptic proteins by tagging them with FPs and their pH-sensitive variants, genetically encoded chromophore-assisted light inactivation (CALI) has been developed to selectively inactivate specific synaptic protein functions that regulate synaptic events such as synaptic release (Lin et al., 2013). CALI is based on light-induced generation of reactive oxygen and the consequent inactivation of nearby attached synaptic proteins. Its original agents were synthetic chromophores for example malachite green (Jay, 1988), fluorescein (Beck et al., 2002), FlAsH (Marek and Davis, 2002), ReAsH (Tour et al., 2003), and eosin (Takemoto et al., 2011) and FPs such as KillerRed (Bulina et al., 2006). To precisely inhibit synaptic release with improved target specificity and inactivation efficiency compared to these CALI agents, inhibition of synaptic release with CALI (InSynC) has been recently developed using a newly engineered flavoprotein called mini small singlet oxygen generator (miniSOG), fused with the SNARE proteins VAMP2 and synaptophysin (Lin et al., 2013). miniSOG was originally derived from the light, oxygen, and voltage 2 (LOV2) domain of phototropin, a blue light photoreceptor (Shu et al., 2011). Under blue light illumination, this photoreceptor binds to and excites flavin mononucleotide (FMN), which then functions as an oxygen generator in cells. miniSOG contains the single amino acid substitution of FMN-binding residue Cys426 to Gly on the LOV2 domain, allowing for more efficient energy transfer to FMN, and contains further mutations for enhanced brightness. When illuminated by blue light, synaptic proteins can be selectively inactivated by miniSOG-mediated oxidization of susceptible residues such as tryptophan, tyrosine, histidine, cysteine, and methionine. InSynC by miniSOG can selectively inhibit vesicle release at individual synapses in vitro and in vivo thanks to the high efficiency of its light-induced oxygen generation, independence of exogenous cofactors, and small size (106 residues, 14 kDa; Lin et al., 2013). However, further engineering is required for investigating the functional dynamics of synaptic circuits with physiologically relevant temporal resolutions, as inactivation by InSynC persists relatively long (~1 h) after light stimulation.

Time-Specific Tagging for the Age Measurement of Proteins (TimeSTAMP)

Another new strategy beyond merely visualizing synaptic proteins by tagging with FPs is time-specific tagging for the age measurement of proteins (TimeSTAMP; Lin et al., 2008). As spatiotemporally controlled protein synthesis and trafficking are critical for synaptogenesis, synaptic connectivity, and long-lasting changes in synapses, TimeSTAMP is beneficial for tracking important, newly synthesized synaptic proteins such as PSD-95 and CaMKII in living neurons. TimeSTAMP is a drug-controllable, time-specific tagging strategy based on the hepatitis C virus NS3 protease and its cell-permeable inhibitor BILN-2061. PSD-95-GFP, for example, was fused to NS3 protease flanked by NS4A/B target sites and the C-terminal HA tag (PSD-95-GFP-TS-HA). In the absence of the specific inhibitor BILN-2061, NS3 protease cleaves the NS4A/B target sites allowing the C-terminal HA-tag to be cleaved from PSD-95-GFP and degraded; but drug application will allow the HA-tag to be accumulated. This allows distinguishing between newly and previously synthesized PSD-95 by measuring HA/GFP signals at a time defined by the drug application. For the TimeSTAMP strategy, the NS3 protease domain was chosen because it is small (19 kDa) and monomeric, specific to its substrate, and not cytotoxic, and most of all, NS3 shows high selectivity and efficiency of its cell-permeable inhibitor.

Although the first version of TimeSTAMP has worked successfully in primary hippocampal neurons to track PSD-95 accumulation during synaptic growth, and in Drosophila for whole-brain mapping of newly synthesized CaMKII, it required post hoc immunostaining against epitope tags, limiting the benefits of pulse-chase labeling through time. Thus, TimeSTAMP2 has been introduced, replacing HA-tag with split-fluorescence proteins (e.g., Yellow fluorescent protein, YFP; Orange fluorescent protein, OFP). In fluorescent TimeSTAMP2, for instance, Venus yellow fluorescent protein is separated by an NS3 domain flanked by NS4A/B target sites into VenusNT (1-158 aa) and VenusCT (159-238 aa) for drug-dependent fluorescence. In the absence of BILN-2061, VenusCT is cleaved and degraded by the active NS domain resulting in no yellow fluorescence, while VenusNT and CT are reconstituted as fluorescent forms after drug application. This allows optical pulse labeling of synaptic proteins such as PSD-95 and Neuroligin with a drug-defined temporal resolution. Additionally, photo-oxidizing TimeSTAMP using miniSOG inserted into TS:YFP can be used to visualize new proteins at an EM-based ultrastructural level (Butko et al., 2012).

Dual Component Synaptic Detection

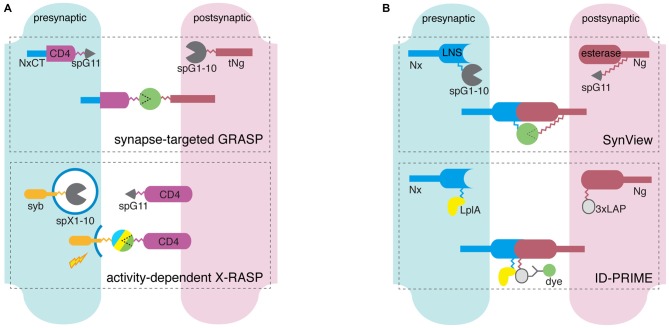

Thus far, we have described methods for detecting synapses by labeling single components, either pre- or post-synaptic. Although these single-component tools allow for detecting, measuring, and manipulating synaptic structures and activities, they do not address the critical fact that synapses are bilateral microstructures involving both presynaptic terminal and postsynaptic density. For reliable synapse detection, therefore, several recent studies introduced new methods for labeling synaptic interactions between pre- and post-synaptic components, such as using split-FPs or enzymes to label neurexin-neuroligin interactions. Here we review dual-component methods using handshaking-like transmembrane molecular interaction across the synaptic cleft, with particular attention to GFP Reconstitution Across Synaptic Partners (GRASP; Figure 2, Table 1).

Figure 2.

Scheme of dual component synapse detectors. (A) GFP reconstitution-dependent molecular tools detect pre- and postsynaptic membrane apposition through the reconstitution of spGFP fragments each attached to the extracellular ends of membrane protein carriers. Synapse-targeted GFP Reconstitution Across Synaptic Partners (GRASP) utilizes a presynaptic component of spGFP11 (spG11, circular wedge) linked to a CD4-neurexin-1β C-terminus (NxCT) fusion through flexible peptide linkers (gray zigzag), and a postsynaptic component of spGFP1-10 (spG1-10) and truncated neuroligin-1 (tNg) connected with a linker. SpG11 and spG1-10 unite at synapses, not random membrane contacts. In activity-dependent X-RASP the presynaptic split-XFP1-10 (spX1-10) is fused to SNARE proteins such as synaptobrevin (syb), and unites with CD4-bound spG11 when presynaptic activity triggers vesicle release. (B) Neurexin (Nx)-neuroligin (Ng) interaction-dependent molecular tools detect individual synapses through fluorescent protein (FP)-based (SynView) and enzymatic reaction-based (Interaction-Dependent Probe Incorporation Mediated by Enzymes, ID-PRIME) direct visualization of Nx-Ng interaction. In SynView, spG11 is inserted between the esterase and proximal extracellular domain of Ng, and spG1-10 in the middle of the LNS domain of Nx. GFP reconstitutes when Nx and Ng unites. ID-PRIME uses the identical set of synaptic protein carriers, but tandem LAP tags (3xLAP) and lipoic acid ligase A (LplA) are attached to C-terminus of Ng esterase domain and Nx LNS domain, respectively. Nx-Ng interaction initiates LplA-mediated lipoic acid tagging to 3xLAP, and signals useful for imaging originate from antibody-fluorophore conjugates.

Mammalian GFP Reconstitution Across Synaptic Partners (mGRASP)

To detect particular synaptic connections with LM, the Mammalian GFP Reconstitution Across Synaptic Partners (mGRASP) technique takes advantage of the complementarity of two non-fluorescent split-GFP fragments, each of which is tethered specifically to the pre- and postsynaptic membrane, respectively (Kim et al., 2012). When two neurons, each expressing one of the fragments, are closely opposed across a synaptic cleft, the split fragments are reconstituted as fluorescent GFP in that location. This dual component synapse detection bypasses the Abbe’s diffraction limit and allows relatively rapid and accurate synapse mapping with LM. This method takes advantage of the fast folding kinetics and stability after maturation of superfolder GFP (Pédelacq et al., 2006), split into two fragments, namely spGFP1-10 (first 214 residues comprising ten β barrels) and spGFP11 (16 residues, 11th β-barrel strand). The GRASP technique was initially implemented in C. elegans (Feinberg et al., 2008; Park et al., 2011) and later in Drosophila (Gordon and Scott, 2009; Fan et al., 2013; Gorostiza et al., 2014). In the original GRASP constructs, membrane carriers (human CD4) for split-GFP fragments were not synapse-specific—fluorescence could arise wherever any membranes expressing fragment pairs were closely apposed. This became a critical issue for mammalian synapse detection because the mammalian nervous system contains much more compactly intermingled neurites than the invertebrate nervous system.

In a previous study, we engineered and successfully applied mGRASP for mapping fine-scale synaptic connectivity in the mouse brain (Kim et al., 2012). The primary features of mGRASP include targeting specific synapses, and matching the approximately 20 nm-wide synaptic cleft without gross changes in endogenous synaptic organization and physiology. Based on published sequences from NCBI, we generated synapse-specific chimeric carriers. Both the pre- and postsynaptic mGRASP components share a common six-subcomponent framework: (1) a signal peptide; (2) a split-GFP fragment; (3) an extracellular domain; (4) a transmembrane domain; (5) an intracellular domain; and (6) a fluorescent protein for neurite and soma visualization. The presynaptic mGRASP component consists of the signal peptide of nematode β-integrin (PAT-3, residues 1–29), GFP β-strand 11 (spGFP11, 16 residues), two flexible GGGGS linkers, the extracellular and transmembrane domains of human CD4-2 (residues 25–242). Rat neurexin-1β (residues 414–468) containing the PDZ-binding motif constitutes the intracellular domain for maintenance of correct localization at the presynaptic site. mCerulean is fused to the intracellular end of the presynaptic mGRASP to visualize axonal expression. The postsynaptic mGRASP component is based primarily on mouse neuroligin-1, which interacts with presynaptic adhesion proteins including β-neurexins, and mediates the formation and maintenance of synapses between neurons. To prevent nonspecific synaptogenesis through interactions with its endogenous partner, neurexin, the extracellular esterase domain of neuroligin is deleted in the main skeleton of the postsynaptic mGRASP. Similar to presynaptic mGRASP, post-mGRASP is composed a signal peptide from the esterase-truncated neuroligin-1 (residues 1–49), GFP β-strand 1-10 (spGFP1-10, 648 residues), the extracellular, transmembrane, and intracellular regions of neuroligin (71, 19, and 127 residues, respectively), followed by the self-cleavable 2A peptide-fused dTomato for visualizing postsynaptic neuronal morphology. This optimized mGRASP enabled the comprehensive synaptic connectivity mapping of hippocampal CA3-CA1 and identified spatially structured patterns of synaptic connectivity (Druckmann et al., 2014). It is important to note that brain-wide synapse detection for comprehensive fine-scale mapping becomes achievable not only by advanced molecular engineering to label the synapse such as mGRASP, but also by appropriately engineered computational analysis (Feng et al., 2012, 2015).

Current GRASP technology has proved to be a tool suitable for rapid and accurate mapping of synaptic connectivity in nematode (Feinberg et al., 2008), fruit fly (Gordon and Scott, 2009), and mouse (Kim et al., 2012; Druckmann et al., 2014). Yet, further improvements to GRASP such as multi-colored FPs for analyzing convergent synaptic inputs, various carriers for neural activities, and tailored computational analyses will provide a clear overview of complex synaptic connectivity and its operation. We next discuss recent efforts in these directions.

Engineering FPs for Multi-Color GRASP

A neuron oftentimes receives multiple inputs from different presynaptic neurons of distinct cell types and/or various brain areas. For comprehensive mapping of complex synaptic circuits, multiple synaptic detection is beneficial, as described earlier in the section describing pH-sensitive FPs. The current version of GRASP restricts convergent synaptic mapping because it relies on only a single pair of spGFP fragments such that spectral overlap of its signals hinders simultaneous imaging with previously well-established GFP-based tools such as GCaMP. Therefore, the multi-color GRASP (XRASP) components have been developed recently (Macpherson et al., 2015; Li et al., 2016). Given that Cyan fluorescent protein (CFP), GFP, and YFP have identical structures except for several residues in the chromophore located in beta barrels of 1-10, C-RASP and Y-RASP were generated by color-shifting mutations in spGFP1-10 (Y66W, S72A, F145A*, N146I, and H148D for C-RASP, *additional mutation in Li et al., 2016, T65G, V68L, S72A and T203Y for Y-RASP) paired with the unaltered spGFP11 (Li et al., 2016). Multi-color GRASP (XRASP) was tested in vivo in several circuits, including the Kenyon cells of the mushroom body, and projection neurons of the thermosensory and olfactory systems in the fruit fly. Reconstructed CFP and YFP signals showed minimal spectral overlap with the GRASP emission and excitation spectra. Extended choices of multi-color GRASP (XRASP) will allow simultaneous imaging of multiple, convergent connectivity and functional activity. However, more red-shifted XRASP is required for in vivo 2-photon imaging together with Ca2+ indicators and for fine-scale synapse labeling from multiple inputs within the single neuron, because it has proved difficult to separate CFP/GFP/YFP signals in the complex mammalian nerve system.

Engineering Carriers for Activity-Dependent GRASP

To understand functional organizations underlying complex brain functions that go beyond structural connectivity patterns, it will be essential to identify active synaptic connectivity at defined times and conditions. For the activity-dependent GRASP system, synaptobrevin (syb), a key constituent of synaptic vesicle membrane, was used as a synaptic carrier instead of constantly membrane-targeted carriers in the previous GRASP systems. The straightforward fusion of syb and spGFP1-10 (syb:spGFP1-10) with the original CD4:spGFP11 can together form activity-dependent GRASP, called the syb:GRASP system. Given activity-dependent interactions of syb with SNARE-SM protein complex triggering synaptic vesicle release, syb:GRASP showed preferential labeling of active synapses as a boost of GRASP fluorescence signals in well-studied thermosensory and olfactory circuits in the fruit fly (Macpherson et al., 2015). This new strategy for mapping active synaptic connectivity might expedite the mapping of functional connectivity at the synapse level in a way previously achieved only by difficult combinations of Ca2+ imaging and exhaustive EM reconstruction (Bock et al., 2011; Briggman et al., 2011). Yet, these new techniques raise basic concerns about possible side effects caused by the overexpression of key synaptic vesicle proteins, and need further optimization before they can be applied to mammalian networks.

FP- and Enzyme-Based Visualization of Neuroligin-Neurexin Interaction

An alternative way to detect synapses has been suggested by imaging neurexin-neuroligin interactions. Presynaptic neurexin and postsynaptic neurolign are transmembrane adhesion proteins and their interaction at the synaptic cleft has been believed to be a key process for synaptic formation, maintenance, and connectivity (Li and Sheng, 2003; Graf et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2010; Krueger et al., 2012). Therefore, it is thought that identifying sites of neurexin-neuroligin interactions could provide selective visualization of synapses. Similar to the GRASP approaches, this method, based on neuroligin-neurexin interactions using splitGFP, is called SynView. It is composed of spGFP1-10-inserted neurexin-1β between residues N275-D276 or A200-G201 for the presynaptic component, and the split-GFP11-inserted neuroligin-1 in the C-terminal end of the extracellular esterase (between Q641-Y642) for the postsynaptic component (Tsetsenis et al., 2014). Another method for visualizing neuroligin-neurexin interactions is based on mutated bacterial lipoic acid ligase (LpIA) and lipoic acid acceptor peptide (LAP) tags (Uttamapinant et al., 2010, 2012), and is called Interaction-Dependent Probe Incorporation Mediated by Enzymes (ID-PRIME; Liu et al., 2013). Using the same principle of SynView, ID-PRIME was designed to detect trans-synaptic contacts of neurexin and neuroligin enzymatically using lipoic acid. These two methods successfully imaged the direct interactions of neurexin-neuroligin synaptic adhesive molecules. However, these methods seem restricted to particular investigations of the dynamics of neurexin-neuroligin, rather general synaptic mapping. In addition, it is known that overexpressing these synaptic adhesion molecules causes substantial structural and physiological perturbations of normal synaptic compartments and cleft structures.

Bridging Tools Between Molecular Synapse Detectors and Brain-Wide Synapse Mapping

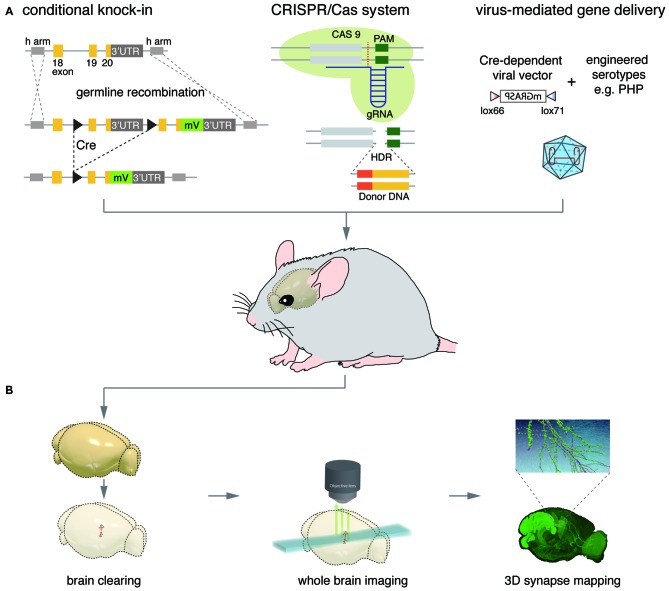

Thus far, we have described methods for detecting synapses focusing on molecular engineering. To exert these genetically encoded synapse detectors to brain-wide synaptic mapping at the system level, there need to be critically partnered technologies such as gene delivery, advanced imaging, and digital representation platform that are appropriate for neural system (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Convergence of technologies for synaptic neuroscience at the systems level. (A) Synapse-detector genes can be delivered to target neural components through germline manipulation-based and viral system-based methods. Exogenous genetic materials can be effectively introduced to the germline with high expression specificity via Cre-mediated conditional knock-in (KI) strategies and the homology directed repair (HDR) pathway of the clustered regularly-interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/Cas system. In a Cre-mediated conditional KI strategy called endogenous labeling via exon duplication (ENABLED), a KI cassette including duplicates of exons 19 and 20 and the 3’UTR of PSD-95 is generated. The first duplicate is flanked by head-to-tail oriented loxP sites (black arrows), while the second duplicate has monovalent Venus (mV) inserted between exon 20 and the 3’UTR. The two duplicate sequences, along with exon 18, are flanked by a set of homology arms (h arm), which mediates KI cassette insertion through homologous recombination. Cre-lox recombination excises the first duplicate containing translation stop signals and polyadenylation sequences, and activates mV expression only in Cre-expressing neurons. Transient expression of sensor genes using viral vectors benefits from efforts to engineer expression through Cre-dependent expression cassettes e.g., Cre-dependent Mammalian GRASP (mGRASP) constructs and newly engineered serotypes that have more selective tropism and transduction efficiency (e.g., AAV-PHP.B). Local tissue or systemic injection of such viral systems can lead to flexible, versatile gene delivery in mature organisms. (B) Combination of light-favoring brain clearing, whole-brain imaging, and computational techniques for three-dimensional synapse mapping enables single-synapse level analysis of synaptic profiles across the whole brain. Further improvements in lipid extraction, refractive index matching, advanced light-sheet microscopy, and large-scale data processing and 3D reference space generation will accelerate systems neuroscience at the synaptic scale.

Gene Delivery System for Synapse Detectors in the Mouse Brain

Improving the targeting specificity for types of cells and scaling up the scope of synaptic sensor delivery are among the crucial initial steps needed to expand single-synapse level analysis to systems level neuroscience. Gene delivery technologies, particularly for the nervous system, have developed at a breathtaking pace over the past decades, establishing methodologies that can be classified into two main categories: germ line manipulation and viral injection.

Genetic Manipulation-Based Gene Delivery

To avoid side effects that can sometimes be caused by the overexpression of FP-tagged synaptic proteins, and to mimic expression patterns of endogenous proteins, gene knock-in (KI) technology has been used to substitute wild-type genes with FP-tagged copies. For synaptic detectors based on universal synaptic proteins such as PSD-95, however, this standard KI method leads to expression of FP-tagged synapse detectors globally, throughout the brain, which makes it difficult to acquire high resolution images of a particular cell type. Therefore, a recent study introduced a conditional KI strategy called endogenous labeling via exon duplication (ENABLED; Fortin et al., 2014). In the ENABLED strategy, a knocked-in gene cassette is composed of the floxed last exon and 3’UTR of PSD-95 followed by its mVenus-tagged duplicated last exon and 3’UTR. The FP-tagged duplicated gene will be selectively expressed only in Cre-expressing neurons because its translation is designed to be blocked by translation stop signals in the endogenous copy in the absence of Cre recombinase. When this PSD-95-ENABLED mouse line is crossed with a dopaminergic cell-type specific DAT-Cre line, for instance, PSD-95mVenus is expressed specifically in dopaminergic neurons. PSD-95-ENABLED was shown to functionally replace wild-type PSD-95 and to sparsely label a particular cell-type, allowing insights into the detailed distribution and dynamics of synapses. In applying this strategy to a wide variety of synaptic proteins, one concern with using the ENABLED strategy is that it is limited to synaptic proteins that are compatible with C-terminal FP-tagging.

Thanks to incredibly fast developments and improvements in genetic manipulation technologies such as clustered regularly-interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) and effector nucleases Cas system (Cong et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2013; Fujii et al., 2014; Aida et al., 2015), the generation of synapse detector KI mouse lines is becoming time- and cost-efficient, and is dramatically facilitating synapse mapping.

Viral System-Based Gene Delivery

Spatially targeted gene delivery into the mature brain can be achieved through stereotactic microinjection of viral vectors expressing FP-tagged proteins. Diverse virus families have been recruited into this effort: Retroviridae (e.g., lentivirus), Parvoviridae (e.g., rAAV), Adenoviridae (e.g., canine adenovirus), and Alphaviridae (e.g., sindbis virus), including some that cross the synapse, such as Rhabdoviridae (e.g., rabies virus) and Herpesviridae (e.g., HSV-1 and pseudorabies virus; Nassi et al., 2015). Because of their low cytotoxicity and stable expression, lentiviruses and rAAVs are the most widely used viral vectors in neuroanatomical tracing studies and human clinical trials testing gene therapy. In fact, spatially restricted injection of Cre-(in)dependent rAAV vectors have been used for mGRASP-assisted synaptic mapping.

In parallel, ongoing efforts include searching for and engineering new types of virus to allow transduction efficiency/specificity and retrograde infection. Canine adenovirus has drawn attention because of its strong retrograde transport capability and relatively large payload size (~30 kb); further, several successful applications of Canine adenovirus in the mouse brain suggest a powerful complement to the lentivirus and rAAV (Bru et al., 2010; Ekstrand et al., 2014; Junyent and Kremer, 2015; Schwarz et al., 2015). Additionally, systemic delivery of viral vectors in animal models has proved to be effective and safe for various serotypes of AAV (Foust et al., 2009; Bevan et al., 2011; Gray et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2014; Deverman et al., 2016).

Advanced Brain-Wide Imaging and Digital Representation of Synaptic Detectors

Once FP-based synaptic detectors are introduced into the brain as described above, appropriate brain-wide imaging and digital representation technologies are necessary to map synaptic connectivity. Happily, there has been remarkable progress in tissue clearing methodology such as BABB (Dodt et al., 2007), CUBIC (Susaki et al., 2014) 3DISCO (Ertürk et al., 2012), immunolabeling-enabled three-dimensional imaging of solvent-cleared organs (iDISCO; Renier et al., 2014), SeeDB (Ke et al., 2013) and CLARITY (Chung et al., 2013; Tomer et al., 2014) that are needed to prepare the intact brain for imaging while avoiding distortions caused by physical sectioning. These new clearing techniques, together with advanced optical methods such as fluorescent selective plane illumination microscopy (fSPIM; Huisken et al., 2004), will allow high-throughput whole brain imaging. Also, once images are acquired, digital representation programs are necessary to reliably extract synaptic wiring information from the images, and to bring data from different sections and animals into register with one another (Johnson et al., 2010; Oh et al., 2014). Improvements in this software will be greatly beneficial.

In our view, new clearing methods, optics, and tailored computational analysis platforms together with advanced synaptic detectors such as mGRASP are very promising developments for the complete mapping of mammalian synaptic connectivity.

Conclusion and Perspective

Here we reviewed new FP-based synapse detection techniques, which are useful for rapidly imaging individual synapses and synaptic connectivity in the whole brain with LM. Recent technical developments have allowed a focus of neuroscience to move from individual synapses to ensemble interactions among neurons of various cell types through multiple synaptic pathways. Comprehensively mapping individual synapses in the whole brain will provide firm grounds for further anatomical and functional studies and such mapping is essential for analyzing large-scale information processing phenomena. We believe that rapid, scalable synaptic cartography with the triad of single-synapse resolution, brain-wide scope, and cell-type-specific connectivity requires a synergistic combination of advanced technologies, and that FP-based neurosensors are the key to this grand integrative project.

Author Contributions

HL, WCO, JS, and JK wrote this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

HL, WCO, JK, and JS are supported by the Korea Institute of Science and Technology (KIST) Institutional Program (2E26190 and 2N41660, respectively) and the Samsung Science and Technology Foundation.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- 3′UTR

3′ untranslated region

- AMPAR

α-amino-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor

- CA3

Cornu Ammonis 3

- CALI

chromophore-assisted light inactivation

- CaMKII

calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II

- CFP

Cyan fluorescent protein

- CD4

cluster of differentiation 4

- ChR

Channelrhodopsin

- CRISPR

clustered regularly-interspaced short palindromic repeats

- ENABLED

endogenous labeling via exon duplication

- EM

electron microscopy

- FMN

flavin mononucleotide

- FP

fluorescent protein

- fSPIM

fluorescent selective plane illumination microscopy

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- HA

hemagglutinin

- HSV-1

Herpes simplex virus-1

- iDISCO

immunolabeling-enabled three-dimensional imaging of solvent-cleared organs

- ID-PRIME

Interaction-Dependent Probe Incorporation Mediated by Enzymes

- InSynC

Inhibition of Synaptic Release with CALI

- KI

knock-in

- LAP

lipoic acid acceptor peptide

- LM

light microscopy

- LOV2

light, oxygen, and voltage 2

- LpIA

lipoic acid ligase

- mGluR

metabotropic glutamate receptors

- mGRASP

Mammalian GFP Reconstitution Across Synaptic Partners

- miniSOG

mini small singlet oxygen generator

- NCBI

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- NS3

Nonstructural protein 3

- OFP

Orange fluorescent protein

- PDZ

PSD-95, Drosophila disc large tumor suppressor (Dlg1), and zonula occludens-1 protein (zo-1)

- PSD-95

postsynaptic density protein-95

- rAAV

recombinant adeno-associated virus

- SM protein

Sec1/Munc18-like protein

- SNARE

SNAP (Soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein) Receptor

- syb

synaptobrevin

- spGFP

split-GFP

- sypHTomato

Synaptophysin-fused pHTomato

- TimeSTAMP

Time-Specific Tagging for the Age Measurement of Proteins

- VAMP2

vesicle-associated membrane protein 2

- VenusNT

Venus N-terminal

- VenusCT

Venus C-terminal

- VGluT

vesicular glutamate transporter

- YFP

Yellow fluorescent protein.

References

- Ahmari S. E., Buchanan J., Smith S. J. (2000). Assembly of presynaptic active zones from cytoplasmic transport packets. Nat. Neurosci. 3, 445–451. 10.1038/74814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aida T., Chiyo K., Usami T., Ishikubo H., Imahashi R., Wada Y., et al. (2015). Cloning-free CRISPR/Cas system facilitates functional cassette knock-in in mice. Genome Biol. 16:87. 10.1186/s13059-015-0653-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck S., Sakurai T., Eustace B. K., Beste G., Schier R., Rudert F., et al. (2002). Fluorophore-assisted light inactivation: a high-throughput tool for direct target validation of proteins. Proteomics 2, 247–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevan A. K., Duque S., Foust K. D., Morales P. R., Braun L., Schmelzer L., et al. (2011). Systemic gene delivery in large species for targeting spinal cord, brain and peripheral tissues for pediatric disorders. Mol. Ther. 19, 1971–1980. 10.1038/mt.2011.157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock D. D., Lee W.-C. A., Kerlin A. M., Andermann M. L., Hood G., Wetzel A. W., et al. (2011). Network anatomy and in vivo physiology of visual cortical neurons. Nature 471, 177–182. 10.1038/nature09802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggman K. L., Helmstaedter M., Denk W. (2011). Wiring specificity in the direction-selectivity circuit of the retina. Nature 471, 183–188. 10.1038/nature09818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bru T., Salinas S., Kremer E. J. (2010). An update on canine adenovirus type 2 and its vectors. Viruses 2, 2134–2153. 10.3390/v2092134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulina M. E., Chudakov D. M., Britanova O. V., Yanushevich Y. G., Staroverov D. B., Chepurnykh T. V., et al. (2006). A genetically encoded photosensitizer. Nat. Biotechnol. 24, 95–99. 10.1038/nbt1175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butko M. T., Yang J., Geng Y., Kim H. J., Jeon N. L., Shu X., et al. (2012). Fluorescent and photo-oxidizing TimeSTAMP tags track protein fates in light and electron microscopy. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 1742–1751. 10.1038/nn.3246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caroni P., Chowdhury A., Lahr M. (2014). Synapse rearrangements upon learning: from divergent-sparse connectivity to dedicated sub-circuits. Trends Neurosci. 37, 604–614. 10.1016/j.tins.2014.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Akin O., Nern A., Tsui C. Y. K., Pecot M. Y., Zipursky S. L. (2014). Cell-type-specific labeling of synapses in vivo through synaptic tagging with recombination. Neuron 81, 280–293. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.12.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S. X., Tari P. K., She K., Haas K. (2010). Neurexin-neuroligin cell adhesion complexes contribute to synaptotropic dendritogenesis via growth stabilization mechanisms in and in vivo. Neuron 67, 967–983. 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung K., Wallace J., Kim S.-Y., Kalyanasundaram S., Andalman A. S., Davidson T. J., et al. (2013). Structural and molecular interrogation of intact biological systems. Nature 497, 332–337. 10.1038/nature12107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong L., Ran F. A., Cox D., Lin S., Barretto R., Habib N., et al. (2013). Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science 339, 819–823. 10.1126/science.1231143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan W. M., Südhof T. C., Stevens C. F. (2001). Synapses. Baltimore: JHU Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Robertis E. D., Bennett H. S. (1955). Some features of the submicroscopic morphology of synapses in frog and earthworm. J. Biophys. Biochem. Cytol. 1, 47–58. 10.1083/jcb.1.1.47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deverman B. E., Pravdo P. L., Simpson B. P., Kumar S. R., Chan K. Y., Banerjee A., et al. (2016). Cre-dependent selection yields AAV variants for widespread gene transfer to the adult brain. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, 204–209. 10.1038/nbt.3440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodt H.-U., Leischner U., Schierloh A., Jährling N., Mauch C. P., Deininger K., et al. (2007). Ultramicroscopy: three-dimensional visualization of neuronal networks in the whole mouse brain. Nat. Methods 4, 331–336. 10.1038/nmeth1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druckmann S., Feng L., Lee B., Yook C., Zhao T., Magee J. C., et al. (2014). Structured synaptic connectivity between hippocampal regions. Neuron 81, 629–640. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.11.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrand M. I., Nectow A. R., Knight Z. A., Latcha K. N., Pomeranz L. E., Friedman J. M. (2014). Molecular profiling of neurons based on connectivity. Cell 157, 1230–1242. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertürk A., Becker K., Jährling N. J. A., Mauch C. P., Hojer C. D., Egen J. G., et al. (2012). Three-dimensional imaging of solvent-cleared organs using 3DISCO. Nat. Protoc. 7, 1983–1995. 10.1038/nprot.2012.119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan P., Manoli D. S., Ahmed O. M., Chen Y., Agarwal N., Kwong S., et al. (2013). Genetic and neural mechanisms that inhibit Drosophila from mating with other species. Cell 154, 89–102. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg E. H., VanHoven M. K., Bendesky A., Wang G., Fetter R. D., Shen K., et al. (2008). GFP reconstitution across synaptic partners (GRASP) defines cell contacts and synapses in living nervous systems. Neuron 57, 353–363. 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.11.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng L., Zhao T., Kim J. (2012). Improved synapse detection for mGRASP-assisted brain connectivity mapping. Bioinformatics 28, i25–i31. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng L., Zhao T., Kim J. (2015). neuTube 1.0: a new design for efficient neuron reconstruction software based on the SWC format. eNeuro 2, 1–10. 10.1523/ENEURO.0049-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortin D. A., Tillo S. E., Yang G., Rah J. C., Melander J. B., Bai S., et al. (2014). Live imaging of endogenous PSD-95 using ENABLED: a conditional strategy to fluorescently label endogenous proteins. J. Neurosci. 34, 16698–16712. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3888-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foust K. D., Nurre E., Montgomery C. L., Hernandez A., Chan C. M., Kaspar B. K. (2009). Intravascular AAV9 preferentially targets neonatal neurons and adult astrocytes. Nat. Biotechnol. 27, 59–65. 10.1038/nbt.1515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii W., Onuma A., Sugiura K., Naito K. (2014). Efficient generation of genome-modified mice via offset-nicking by CRISPR/Cas system. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 445, 791–794. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.01.141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank D. D., Jouandet G. C., Kearney P. J., Macpherson L. J., Gallio M. (2015). Temperature representation in the Drosophila brain. Nature 519, 358–361. 10.1038/nature14284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Z., Liu J., Guo C., Zhou Y., Teng Y., Liu L. (2010). Two pairs of neurons in the central brain control Drosophila innate light preference. Science 330, 499–502. 10.1126/science.1195993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon M. D., Scott K. (2009). Motor control in a Drosophila taste circuit. Neuron 61, 373–384. 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorostiza E. A., Depetris-Chauvin A., Frenkel L., Pírez N., Ceriani M. F. (2014). Circadian pacemaker neurons change synaptic contacts across the day. Curr. Biol. 24, 2161–2167. 10.1016/j.cub.2014.07.063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf E. R., Zhang X., Jin S.-X., Linhoff M. W., Craig A. M. (2004). Neurexins induce differentiation of GABA and glutamate postsynaptic specializations via neuroligins. Cell 119, 1013–1026. 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray E. G. (1959). Axo-somatic and axo-dendritic synapses of the cerebral cortex: an electron microscope study. J. Anat. 93, 420–433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray S. J., Matagne V., Bachaboina L., Yadav S., Ojeda S. R., Samulski R. J. (2011). Preclinical differences of intravascular AAV9 delivery to neurons and glia: a comparative study of adult mice and nonhuman primates. Mol. Ther. 19, 1058–1069. 10.1038/mt.2011.72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huisken J., Swoger J., Del Bene F., Wittbrodt J., Stelzer E. H. K. (2004). Optical sectioning deep inside live embryos by selective plane illumination microscopy. Science 305, 1007–1009. 10.1126/science.1100035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay D. G. (1988). Selective destruction of protein function by chromophore-assisted laser inactivation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 85, 5454–5458. 10.1073/pnas.85.15.5454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson G. A., Badea A., Brandenburg J., Cofer G., Fubara B., Liu S., et al. (2010). Waxholm space: an image-based reference for coordinating mouse brain research. Neuroimage 53, 365–372. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.06.067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junyent F., Kremer E. J. (2015). CAV-2–why a canine virus is a neurobiologist’s best friend. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 24, 86–93. 10.1016/j.coph.2015.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karuppudurai T., Lin T.-Y., Ting C.-Y., Pursley R., Melnattur K. V., Diao F., et al. (2014). A hard-wired glutamatergic circuit pools and relays uv signals to mediate spectral preference in Drosophila. Neuron 81, 603–615. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke M.-T., Fujimoto S., Imai T. (2013). SeeDB: a simple and morphology-preserving optical clearing agent for neuronal circuit reconstruction. Nat. Neurosci. 16, 1154–1161. 10.1038/nn.3447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller P. J., Schmidt A. D., Wittbrodt J., Stelzer E. H. K. (2008). Reconstruction of zebrafish early embryonic development by scanned light sheet microscopy. Science 322, 1065–1069. 10.1126/science.1162493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Zhao T., Petralia R. S., Yu Y., Peng H., Myers E., et al. (2012). mGRASP enables mapping mammalian synaptic connectivity with light microscopy. Nat. Methods 9, 96–102. 10.1038/nmeth.1784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopec C. D., Li B., Wei W., Boehm J., Malinow R. (2006). Glutamate receptor exocytosis and spine enlargement during chemically induced long-term potentiation. J. Neurosci. 26, 2000–2009. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3918-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger D. D., Tuffy L. P., Papadopoulos T., Brose N. (2012). The role of neurexins and neuroligins in the formation, maturation and function of vertebrate synapses. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 22, 412–422. 10.1016/j.conb.2012.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Guo A., Li H. (2016). CRASP: CFP reconstitution across synaptic partners. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 469, 352–356. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Murthy V. N. (2001). Visualizing postendocytic traffic of synaptic vesicles at hippocampal synapses. Neuron 31, 593–605. 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00398-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Sheng M. (2003). Some assembly required: the development of neuronal synapses. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 833–841. 10.1038/nrm1242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Tsien R. W. (2012). pHTomato, a red, genetically encoded indicator that enables multiplex interrogation of synaptic activity. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 1047–1053. 10.1038/nn.3126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M. Z., Glenn J. S., Tsien R. Y. (2008). A drug-controllable tag for visualizing newly synthesized proteins in cells and whole animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 105, 7744–7749. 10.1073/pnas.0803060105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J. Y., Sann S. B., Zhou K., Nabavi S., Proulx C. D., Malinow R., et al. (2013). Optogenetic inhibition of synaptic release with chromophore-assisted light inactivation (CALI). Neuron 79, 241–253. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.05.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D. S., Loh K. H., Lam S. S., White K. A., Ting A. Y. (2013). Imaging trans-cellular neurexin-neuroligin interactions by enzymatic probe ligation. PLoS One 8:e52823. 10.1371/journal.pone.0052823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macpherson L. J., Zaharieva E. E., Kearney P. J., Alpert M. H., Lin T.-Y., Turan Z., et al. (2015). Dynamic labelling of neural connections in multiple colours by trans-synaptic fluorescence complementation. Nat. Commun. 6:10024 10.1038/ncomms10024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinow R., Malenka R. C. (2002). AMPA receptor trafficking and synaptic plasticity. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 25, 103–126. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marek K. W., Davis G. W. (2002). Transgenically encoded protein photoinactivation (FlAsH-FALI): acute inactivation of synaptotagmin I. Neuron 36, 805–813. 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)01068-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markram H., Lübke J., Frotscher M., Sakmann B. (1997). Regulation of synaptic efficacy by coincidence of postsynaptic APs and EPSPs. Science 275, 213–215. 10.1126/science.275.5297.213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miesenböck G., De Angelis D. A., Rothman J. E. (1998). Visualizing secretion and synaptic transmission with pH-sensitive green fluorescent proteins. Nature 394, 192–195. 10.1038/28190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassi J. J., Cepko C. L., Born R. T., Beier K. T. (2015). Neuroanatomy goes viral!. Front. Neuroanat. 9:80. 10.3389/fnana.2015.00080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson C. D., Kim M. J., Hsin H., Chen Y., Sheng M. (2013). Phosphorylation of threonine-19 of PSD-95 by GSK-3β is required for PSD-95 mobilization and long-term depression. J. Neurosci. 33, 12122–12135. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0131-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh S. W., Harris J. A., Ng L., Winslow B., Cain N., Mihalas S., et al. (2014). A mesoscale connectome of the mouse brain. Nature 508, 207–214. 10.1038/nature13186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palay S. L. (1956). Synapses in the central nervous system. J. Biophys. Biochem. Cytol. 2, 193–202. 10.1083/jcb.2.4.193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palay S. L., Palade G. E. (1955). The fine structure of neurons. J. Biophys. Biochem. Cytol. 1, 69–88. 10.1083/jcb.1.1.69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J., Knezevich P. L., Wung W., O’Hanlon S. N., Goyal A., Benedetti K. L., et al. (2011). A conserved juxtacrine signal regulates synaptic partner recognition in Caenorhabditis elegans. Neural Dev. 6:28. 10.1186/1749-8104-6-28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pech U., Pooryasin A., Birman S., Fiala A. (2013). Localization of the contacts between Kenyon cells and aminergic neurons in the Drosophila melanogaster brain using SplitGFP reconstitution. J. Comp. Neurol. 521, 3992–4026. 10.1002/cne.23388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pédelacq J.-D., Cabantous S., Tran T., Terwilliger T. C., Waldo G. S. (2006). Engineering and characterization of a superfolder green fluorescent protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 24, 79–88. 10.1038/nbt1172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelkey K. A., Yuan X., Lavezzari G., Roche K. W., McBain C. J. (2007). mGluR7 undergoes rapid internalization in response to activation by the allosteric agonist AMN082. Neuropharmacology 52, 108–117. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renier N., Wu Z., Simon D. J., Yang J., Ariel P., Tessier-Lavigne M. (2014). iDISCO: a simple, rapid method to immunolabel large tissue samples for volume imaging. Cell 159, 896–910. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson D. S., Lichtman J. W. (2015). Clarifying tissue clearing. Cell 162, 246–257. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo S. J., Dietz D. M., Dumitriu D., Morrison J. H., Malenka R. C., Nestler E. J. (2010). The addicted synapse: mechanisms of synaptic and structural plasticity in nucleus accumbens. Trends Neurosci. 33, 267–276. 10.1016/j.tins.2010.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankaranarayanan S., Ryan T. A. (2000). Real-time measurements of vesicle-SNARE recycling in synapses of the central nervous system. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 197–204. 10.1038/35008615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz L. A., Miyamichi K., Gao X. J., Beier K. T., Weissbourd B., DeLoach K. E., et al. (2015). Viral-genetic tracing of the input-output organization of a central noradrenaline circuit. Nature 524, 88–92. 10.1038/nature14600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaner N. C., Lin M. Z., McKeown M. R., Steinbach P. A., Hazelwood K. L., Davidson M. W., et al. (2008). Improving the photostability of bright monomeric orange and red fluorescent proteins. Nat. Methods 5, 545–551. 10.1038/nmeth.1209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y., Rosendale M., Campbell R. E., Perrais D. (2014). pHuji, a pH-sensitive red fluorescent protein for imaging of exo- and endocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 207, 419–432. 10.1083/jcb.201404107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen K., Teruel M. N., Connor J. H., Shenolikar S., Meyer T. (2000). Molecular memory by reversible translocation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Nat. Neurosci. 3, 881–886. 10.1038/78783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu X., Lev-Ram V., Deerinck T. J., Qi Y., Ramko E. B., Davidson M. W., et al. (2011). A genetically encoded tag for correlated light and electron microscopy of intact cells, tissues and organisms. PLoS Biol. 9:e1001041. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susaki E. A., Tainaka K., Perrin D., Kishino F., Tawara T., Watanabe T. M., et al. (2014). Whole-brain imaging with single-cell resolution using chemical cocktails and computational analysis. Cell 157, 726–739. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takemoto K., Matsuda T., McDougall M., Klaubert D. H., Hasegawa A., Los G. V., et al. (2011). Chromophore-assisted light inactivation of HaloTag fusion proteins labeled with eosin in living cells. ACS Chem. Biol. 6, 401–406. 10.1021/cb100431e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomer R., Khairy K., Amat F., Keller P. J. (2012). Quantitative high-speed imaging of entire developing embryos with simultaneous multiview light-sheet microscopy. Nat. Methods 9, 755–763. 10.1038/nmeth.2062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomer R., Ye L., Hsueh B., Deisseroth K. (2014). Advanced CLARITY for rapid and high-resolution imaging of intact tissues. Nat. Protoc. 9, 1682–1697. 10.1038/nprot.2014.123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tour O., Meijer R. M., Zacharias D. A., Adams S. R., Tsien R. Y. (2003). Genetically targeted chromophore-assisted light inactivation. Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 1505–1508. 10.1038/nbt914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsetsenis T., Boucard A. A., Araç D., Brunger A. T., Südhof T. C. (2014). Direct visualization of trans-synaptic neurexin-neuroligin interactions during synapse formation. J. Neurosci. 34, 15083–15096. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0348-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien J. Z., Huerta P. T., Tonegawa S. (1996). The essential role of hippocampal CA1 NMDA receptor-dependent synaptic plasticity in spatial memory. Cell 87, 1327–1338. 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81827-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uttamapinant C., Tangpeerachaikul A., Grecian S., Clarke S., Singh U., Slade P., et al. (2012). Fast, cell-compatible click chemistry with copper-chelating azides for biomolecular labeling. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed Engl. 51, 5852–5856. 10.1002/anie.201108181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uttamapinant C., White K. A., Baruah H., Thompson S., Fernández-Suárez M., Puthenveetil S., et al. (2010). A fluorophore ligase for site-specific protein labeling inside living cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 107, 10914–10919. 10.1073/pnas.0914067107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voglmaier S. M., Kam K., Yang H., Fortin D. L., Hua Z., Nicoll R. A., et al. (2006). Distinct endocytic pathways control the rate and extent of synaptic vesicle protein recycling. Neuron 51, 71–84. 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.05.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Yang H., Shivalila C. S., Dawlaty M. M., Cheng A. W., Zhang F., et al. (2013). One-step generation of mice carrying mutations in multiple genes by CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome engineering. Cell 153, 910–918. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B., Treweek J. B., Kulkarni R. P., Deverman B. E., Chen C.-K., Lubeck E., et al. (2014). Single-cell phenotyping within transparent intact tissue through whole-body clearing. Cell 158, 945–958. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Q., Xiang Y., Yan Z., Han C., Jan L. Y., Jan Y. N. (2011). Light-induced structural and functional plasticity in Drosophila larval visual system. Science 333, 1458–1462. 10.1126/science.1207121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamanillo D., Sprengel R., Hvalby O., Jensen V., Burnashev N., Rozov A., et al. (1999). Importance of AMPA receptors for hippocampal synaptic plasticity but not for spatial learning. Science 284, 1805–1811. 10.1126/science.284.5421.1805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y., Xu J., Heinemann S. F. (2009). Two pathways of synaptic vesicle retrieval revealed by single-vesicle imaging. Neuron 61, 397–411. 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]