Abstract

Studies related to ethnomedicines investigate the way people manage illness and diseases because of their cultural perspective. Fields like ecology, epidemiology, and medical history jointly contribute to the broad field of ethnomedical study. The knowledge gathered by traditional healers in the villages and tribal communities on natural medicines remains unfamiliar to the majority of scientists and the general population. The study of ethnomedicine principally involves the compilation of empirical data, particularly the patterns of illness and treatments from folklore. Due to deforestation, and urbanization of the desert jungles, many valuable medicinal plants present in the study areas appear to be facing extinction in the near future if no proper conservation plans are carried out. This survey documented 33 different herbs used by the natives of Oman for various ailments. Parts of a particular plant, fresh or dried, might be crushed and drunk as an infusion or used externally as a poultice, ground into a paste, or inhaled as smoke. The survey identified 22 plant families, and 18 traditional treatment groups.

Keywords: Oman; Medicine, Traditional

Introduction

In Oman, the information on traditional ethnomedicine practice is not transferred from generation to generation in written form but is verbally inherited from the elder members of the family. Traditional medicine is still widely used to treat minor illnesses like colds, fevers, stomach problems, and headaches, even with the availability of primary and secondary healthcare. The elders or trained traditional healers have the right to administer traditional medicines in the society.

The Unani tibb is the base of traditional Islamic medicine and depends on the humoral system, a Graeco-Arab style of medicine.1,2 It is believed to be derived from the ancient Greek medicinal system where the four elements (earth, water, air, and fire) correspond to blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile in the body. A healthy body is considered to have an equilibrium between the four humors and any imbalance may result in sickness. The Greek physician Hippocrates linked the four humors to four basic temperaments and evolved the ancient medical concept of humorism.3,4 These temperaments were sanguine (element: air, people: social type), choleric (element: fire, people: short tempered and extroverts), melancholic (element: earth, people: serious and introverts), and phlegmatic (element: water, people: relaxed and peaceful)

In some Omani villages, when doctors are rare, a hakim (wiseman) dispenses herbal and other forms of medication. The practice is based on practical, common-sense cures derived from some empiric knowledge. Traditional Omani healers base their diagnosis and treatment on the ancient Greek ideas of health and illness as described by Aristotle5 and adapted by medieval Arab medical practitioners. The West used the Greek model for centuries too.

The Oman Animal and Plant Genetic Resource Center (OAPGRC)6 was established in 2012 and has been involved in making action plans for the conservation and maintenance of Oman’s genetic resources like animals, medicinal plants, marine species, and microorganisms. The first Indian Ocean Rim Association’s meeting on medicinal plants was conducted in July 2014, during which the participating countries signed the Salalah Declaration on Applied Research, Technology Transfer and Commercialization of Medicinal Plants and Traditional Medicine.

The hilly ranges at Jebel Akdhar and Dhofar are rich with remarkable flora and fauna and comprise of migratory birds and valuable medicinal plants. The Jebel Akdhar area in Oman, from which medicinal plant data was gathered, is situated at latitude 23.3o 19.8' N and longitude 57.88 ° 52.8' E and 2000 m above sea level. It is one of the highest points in Oman and surrounded by the Al-Hajar mountain range. Dhofar occupies the southernmost province of Oman, famous for its frankincense (luban) trade. Salalah is the capital of Dhofar governorate. Dhofar is situated at latitude 18o, 23.8 ' N and longitude 54o, 26.1' E and 1200 m above sea level.

Survey methodology

We conducted this review between September 2013 and August 2014. Relevant information6-9 was collected through a literature survey of the published ethnobotanical and biodiversity books, monographs or papers on herbal medicines found in the Jebel Akdhar and Dhofar regions of Oman

Additionally, interviews were conducted in villages with the traditional medicine people, folklore groups, and native informants to gather information on the inherited knowledge and empiric experiences about the healing properties of local plants. Each herbal traditional use/evidence was considered authentic only after validation through three or more informants from village localities and cross checking the information at different times. Samples of all medicinal plants were identified and authenticated by experts on plants’ taxonomy at the Department of Science, Higher College of Technology, Muscat.

The mode of preparation of the crude drugs and the methods of their administration were recorded. Most plants are used as infusions, decoctions, pastes, or inhalants.

The Dhofar plains form a wide coastal belt between the mountain ridges and the Arabian sea and stretches around 20–25 km. They are composed of marine and aeolian sand and alluvial limestone gravels and are navigated by a network of several wadis that drain out from the mountains. The soils in such areas are shallow and support vegetation of xerophytic shrubs. The genus, species, and families of the identified herbs are arranged in alphabetical order [Table 1].

Table 1. Traditional medicines of Oman.

| Name of the herb | Local name (Arabic) | Botanical name (family name) | Major chemical constituents | Uses | Reference | Herbarium accession number | Extraction methods/decoctions used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rose water | Ward |

Rosa damascena (Rosaceae) |

Citronellal, geraniol, methyl euginol, linalool, vitamin C, kaempferol, and quercetin | Astringent, cardiac and cephalic tonic. Used as eye drops. | 10 | DCHM/23 | Aqueous water distillate. |

| Garlic | Thom, kurath |

Allium sativum (Lilliaceae) |

Aliin, allicin, diallyl trisulfide, S-allyl cysteine, ajoene S-allyl mercapto cysteine |

Fever, pulmonary infections, rheumatism, hypoglycemic, purgative. | 11 | DC/HM/24 | Water distillation. |

| Thyme | Zaater |

Thymus vulgaris (Labiatae) |

α -pinene, camphene, β-pinene, α-terpinene, thymol |

Carminative, spasmolytic. | 12 | DC/HM/25 | Extracted from the fresh or partly dried flowering tops and leaves of the plant by water distillation. |

| Acridocarpus | Qafas |

Acridocarpus orientalis (Malpighiaceae) |

Flavonoids morin, polyphenols, phenolics | Headaches and muscle pain. | 13 | DC/HM/26 | Decoction made from crushed seeds. |

| Cinnamon | Qurfa |

Cinnamomum zeylanicum (Laraceae) |

eugenol, eugenol acetate, cinnamic aldehyde and benzyl benzoate | Infection of the respiratory tract, rheumatism, arthritis, general pains. | 14 | DC/HM/27 | The water distillate/decoctions of the leaves and twigs or inner dried bark. |

| Clove | Qurnfel |

Eugenia caryophyllus (Myrtaceae) |

euginol, euginol acetate, iso-eugenol and caryophyllene |

Acne, bruises, burns and cuts, for toothache, mouth sores. | 15 | DC/HM/28 | Water distillate of clove buds. |

| Hemp | Al-keef |

Cannabis sativa (Cannabinaceae) |

Leaf: tetra hydro cannabinol Oil: rich in proteins and vitamins |

Retentive, anesthetic, astringent, sedative. |

16 | DC/HM/29 | The oil is expressed by applying pressure. |

| True myrtle | Yas |

Myrtus communis (Myrtaceae) |

myrtenyl acetate, 1, 8-cineole, limonene, linalool, methyl eugenol, terpineole, trans-carveole, geraniol |

Used in scorpion sting, burns, sores and ulcers. Antiseptic, antirheumatic. |

17 | DC/HM/30 | Myrtle oil is extracted from the leaves, branches, fruits and flowers through water distillation. |

| Senna leaves | Sana makki |

Cassia acutifolia (Leguminosae) |

Sennocides A,B,C,D | Laxative. | 18 | DC/HM/31 | Leaf and root decoction. |

| Juniper | Arar |

Juniper excelsa (Cupressaceae) |

α-pinene, camphene, β pinene, 1,4-cineole limonene, camphor, linalool | Aromatic, stimulant, digestive, diuretic. | 19 | DC/HM/32 | Juniper oil is extracted from dried, crushed or slightly dried ripe fruit or leaves by water distillation. |

| Frankincense | Mohor, Sheehaz mogar |

Boswellia carteri or B.sacra (Burseraceae) |

Limonene, verbenone, incensol | Asthma, wounds, ulcers, bronchitis, diuretic, tonic for cleansing the digestive system and for deodorizing the mouth. |

20 | DC/HM/33 | Oleoresin is collected from cut made in the bark of the tree. |

| Mountain/felty germander or Cat thyme |

Kalpooreh, qasba |

Teucrium mascatense (Lamiaceae) |

Flavonoids | Antibacterial, antinociceptive, antinflammatory, bitter tonic febrifuge. |

21,22 | DC/HM/34 | Water extract of the leaves and stem. |

| Bitter apple | Sharinjiban, mazi |

Solanum incanum (Solanaceae) |

Steroid alkaloid, solanin, solasonine |

Hemorrhoids, earache. | 23 | DC/HM/35 | Water extract of the roots. |

| St Joseph’s wort, sweet basil | Theemran zawab |

Ocimum basilicum (Lamiaceae) |

Thymol, euginol, 1,8 cineole | Colds and eye problems, insect bites. | 24 | DC/HM/36 | Leaf extract. |

| Jacobeastrum arabicum | Kabouv |

Euryops arabicus (Compositae) |

Volatile oil, secoeurabicanal | Analgesic. | 25 | DC/HM/37 | Aqueous Leaf extract. |

| Cumin | Kimoon or Sanoot |

Cuminum cyminum (Umbelliferae) |

Cuminaldehyde, cymene | Enhancing appetite, boiling the ground seeds with lime and then drunk as a colic. | 26 | DC/HM/38 | Decoction of the seeds. |

| Papaya fruits | Pawpaw or fifay |

Carica papaya (Caricaceae) |

Papain enzyme, lycopene, polyphenols | Diarrhea. | 27 | DC/HM/39 | Leaves and seeds. |

| Walnuts | Joz or nakash |

Juglans cinerea (Juglandaceae) |

Nutrient-dense | Eczema. | 28,29 | DC/HM/40 | Leaf juice. |

| Rhazya | Harmal |

Rhazya stricta (Apocynaceae) |

Alkaloids | Smoke from its dried leaves is inhaled from a pipe for chest ailments. | 30 | DC/HM/41 | Dried leaf smoke, leaf juice. |

| Miracle tree | Shu |

Moringa peregrina (Moringaceae) |

Flavonoids rutin, quercetin β-sitosterol, β-amyrin |

Seed oil is used for bone setting. | 31 | DC/HM /42 | Crushed seed oil. |

| Aloe plant | Isqal,sabbar |

Aloe barbedensis A.dhofarensis, A.innermis (Lilliaceae) |

Anthracene glycosides | Purgative, eye infections, wound healing. | 32 | DC/HM/43 | Dried or fresh leaf juice. |

| Lycium | gharqad |

Lycium shawii (Solanaceae |

Alkaloids, steroids, flavonoids | Detoxification, anti-inflammatory, for sore eyes | 33 | DC/HM/44 | Decoction of stem. |

| Bitter apple | handal |

Citrullus colocynthis (Cucurbitaceae) |

Flavonoids, unsaturated fatty acids, alkaloids | Dog and insect bites. | 34,35 | DC/HM/45 | Decoction of the berries, whole plant. |

| Spurge tree | Labna |

Euphorbia larica (Euphorbiaceae) |

Flavonoids | Bites, boils, burns. | 36 | DC/HM/46 | Latex from the tree stem. |

| Rubber bush Camel weed |

shakr |

Calotropis procera (Asclepidaceae) |

Cardiac glycosides | Arthritis. | 37 | DC/HM/47 | Plant milky sap extract. |

| Thorn apple/ Night shade |

Mazi |

Solanum incanum (Solanaceae) |

Steroidal glycosides, steroidal alkaloids | Hemorrhoids, eye and ear infections. | 38 | DC/HM/48 | Leaves, whole plant. |

| Ginger | Zanjabil |

Zingiber officinale (Zingiberaceae) |

Oleoresins | Stomach ailments. | 39 | DC/HM/49 | Rhizomes. |

| Angels trumpet | Tatorah |

Datura metel (Solanaceae) |

Tropane alkaloids | Sedative, used to treat asthma. | 40,41 | DC/HM/50 | Decoction of seeds. |

| Namaqua fig | Tha’ab |

Ficus cordata (Moraceae) |

Polyphenols, flavonoids | Bites, boils, burns. | 42 | DC/HM/51 | Tree sap. |

| Red thorn | Thbeean |

Acacia gerardii (Fabaceae) |

Polyphenols, catechins | Bites, boils, burns. | 43 | DC/HM/52 | Plant resins. |

| Khejri | Ghaf |

Prosopis cineraria (Fabaceae) |

Polyphenols, catechins, Flavonoids, 5HT |

Astringent, demulcent. | 44 | DC/HM/53 | Gum and resins. |

| Dates | Nakhleh |

Phoenix dactylifera (Arecaceae) |

Flavonoids, tannins, vitamins, minerals, sterols | General tonic, cooling, aphrodisiac, bronchitis. | 45,46 | DC/HM/54 | Fruits, leaves, seeds. |

| Caralluma | Qahr al-luhum |

Caralluma flava (Asclepidaceae) |

Pregnane glycosides, flavone glycosides | Tonic, stomach ailments, suppress hunger. | 47 | DC/HM/55 | Aerial part, whole plant. |

The majority of Omani traditional treatments include lime, honey, and garlic10 as herbal additives for treating wounds, the common cold, throat infections, diabetes, and obesity.

Aqueous decoctions of the herbs like cinnamon bark,11 cloves,12 true myrtles,13 frankincense,14 and ginger15 are used to treat infections of the respiratory tract and stomach disorders. Leaf and stem decoctions of the plant Teucrium mascatense are used in traditional Omani medicine as a febrifuge [Figure 1].16,17

Figure 1.

Teucrium mascatense found in the Jebel Akdhar region. The water extract of the leaves and stem is useful as a febrifuge and antibacterial.

The traditional wisdom accumulated over generations of trial and error may result in fatal errors due to ignorance of the toxicities of plant chemical compounds. For example, certain plant chemical compounds are more concentrated at particular times of day, due to diurnal variations, so preparing the correct concentration or dilution of natural herbal treatment is essential.

Rose water18 is used in folk medicine mainly for eye disorders as well as an astringent and cardiac and cephalic tonic. Thyme19 and juniper20 are utilized for their carminative, digestive, diuretic, and spasmolytic properties. Hemp21 or al keef is used in traditional medicine as an astringent, sedative, anesthetic, and retentive. Solanum incarnum22 or bitter apple is used for earache and hemorrhoids. Myrtle or Myrtus communis,23 which is called yas in Arabic, grows on the banks of the wadis (valleys that are dry except following rains), and is used for the cure of ulcers, burns, and scorpion stings. Senna leaves (Sana makki)24 are used widely as a laxative. Ocimum basilicum,25 otherwise known as sweet basil, is an important plant rich in its thymol content. The sweet basil is used widely in Oman by local healers as a cure for the common cold, eye infections, and sore throat. The oil is made by boiling the leaves of juniper and wild olives with fixed oils are used effectively by the local hakims for the treatment of pain from mountain climbing. The aqueous leaf extract of Euryops arabicus26 or kabouv is used as an analgesic.

Cumin seeds (kimoon) are used to improve the appetite.27 Papaya fruit juice is used to treat diarrhea and walnut leaf juice is applied topically for calm skin conditions like eczema. The leaves and seeds of papaya are used to treat diarrhea.28

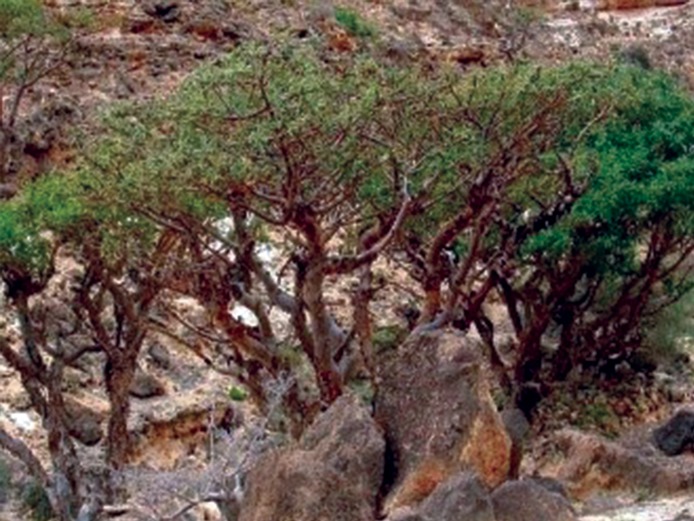

Frankincense, otherwise known as Boswellia carteri14 [Figure 2] is a useful Omani traditional remedy for bronchitis, and can be used as a tonic for cleansing the digestive system, a mouth cleanser, for asthma and ulcers, and as a diuretic. The plant is found largely in the Dhofar region. Solanum incanum29,30 is known as sharinjiban or mazi and used to treat hemorrhoids and eye and ear infections.

Figure 2.

Boswellia carteri found in the Jebel Akdhar region. Oleoresin is collected from the bark of the tree and is used in asthma and for healing wounds and ulcers.

A decoction made from ginger roots15 is used mainly to relieve stomach ailments in the traditional practices. Datura seed decoction31,32 is used as a sedative or sometimes to treat asthma and the tree sap of Ficus cordata (Tha’ab)36 is used in bites, boils, and burns.

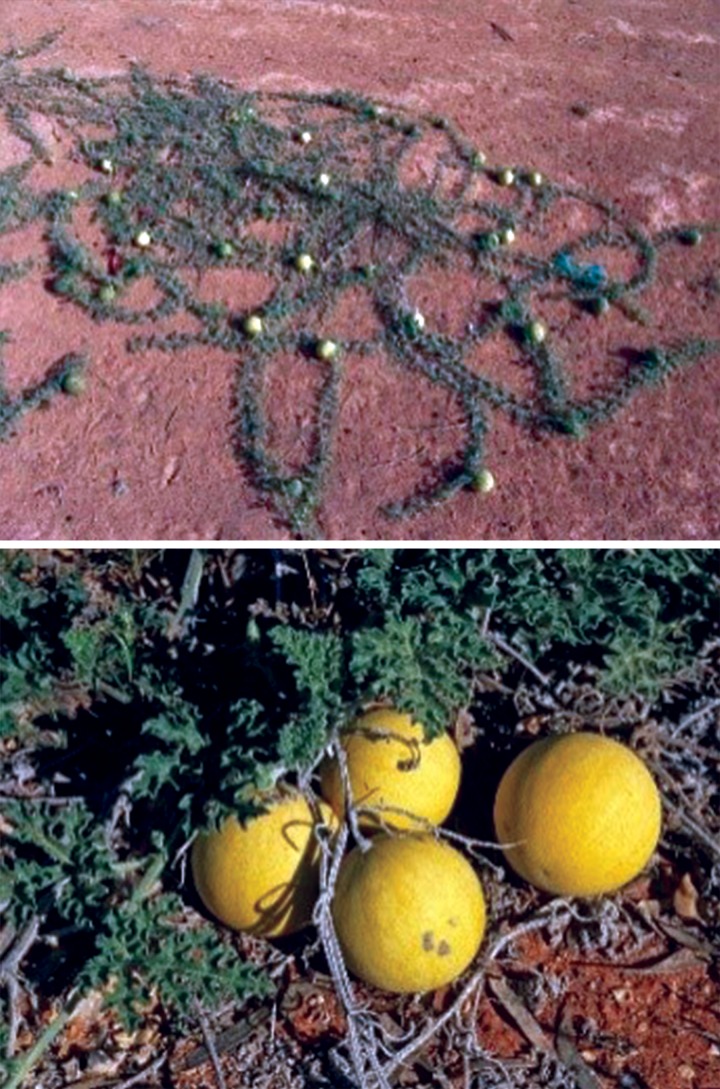

Acridocarpus orientalis23 is used by the locals of the Jebel Akdhar mountain range and also in the sandy plains of western Gulf countries like Oman, Yemen, and the UAE, for headaches. A poultice or paste is made from the crushed seeds and applied to the forehead to relieve headache. In Oman, villagers use the seeds of this plant as a source of yellow dye. Citrullus colocynth22,34 is found scattered in the sandy soil of desert plains bearing green and yellow round gourd included in Cucurbitaceae family. The fruits have astringent and laxative properties. Traditional healers used the fruit juice as a remedy for insect and dog bites. The leaf juice of the walnut plant (Joz or nakash)35,36 is used to treat skin infections and eczema.

In traditional practices, the smoke from the dried leaves of harmal (Rhazya stricta)37 are inhaled to treat bronchial infections. Harmal is also used for treating eye infections, skin rashes, worm infestations, and in diabetes.

Moringa peregrina,38 otherwise known as miracle tree or shu, is mainly used for nutrition, and the crushed seeds are used to cure constipation and other stomach ailments. The shu oil is used traditionally for bone setting by applying it to the skin. The milky sap extract from the Calotropis procera plant is used in folk medicine for arthritis [Figure 3].39

Figure 3.

Calotropis procera found in the Jebel Akdhar region. The milky sap extract of this plant is used in the treatment of arthritis.

The dried Isqal juice obtained from the common garden aloe plants (Aloe barbedensis)40 is used for its cleansing, antimicrobial and wound healing properties. The fresh juice obtained from the plant is useful for eye infections. A decoction of the stem of the plant Lycium shawii,41 known as gharqad, is used to purify and detoxify the digestive and circulatory systems.

The folk medicine men of Oman frequently use resins, latex, and tree saps to dress wounds arising from burns, bites, and boils. The commonly used plants are Acacia gerardii [Figure 4],42 Euphorbia larica [Figure 5]43 and Ficus cordata.36

Figure 4.

Acacia gerardii found in the Dhofar region. The plant resins are used in the treatment of bites, boils, and burns.

Figure 5.

Euphorbia larica found in the Dhofar region. Latex from the tree stem is used for the treatment of bites, boils, burns.

Prosopis cineraria44 is a very popular plant, the gum and resins of which are useful as an astringent and demulcent. Also, date palms (Phoenix dactylifera)45,46 are considered a general tonic, rejuvenator, and cooling agent in traditional medicine practice. A xerophytic plant which can be found abundantly in the Al Fazayeh region of Dhofar is Caralluma flava.47 Natives use these cactus varieties to suppress hunger, stomach ailments and as a general tonic.

Summary

This review focused on the folklore information available on medicinal plants in Oman. We identified 33 medicinal plants routinely used in the folk medicine practice. These plants are included in 22 plant families and 18 traditional treatment groups. Most of the plants are used as infusions, pastes, or inhalants.

Aloes and Senna are the most common laxatives used to relieve constipation in folklore medicine. Rose water, clove, Teucrium plants, and Ocimum herbs and shrubs are the major antimicrobial agents. Plants like garlic, cat thyme, arabicum, and Lycium are used for their antipyretic and antiinflammatory properties. Acidocarpus, Euryops and Teucrium are utilized for their analgesic activity, and the plant Teucrium is a good bitter tonic. Datura seeds, Boswellia, cinnamon, and garlic are utilized for respiratory tract infections. Plants like Calotropis, cinnamon, garlic and true myrtle are used as antiarthritic and antirheumatic agents.

Acacia gerardii, Ficus cordata [Figure 6], Euphorbia larica, and Ocimum basillicum, are used for bites, boils, and burns, and Juglans cinerea (walnut) for skin infections and eczema. Datura seeds and cannabis are used as sedatives. The smoke from the dried leaves of Rhazya stricta [Figure 7] is inhaled from a pipe for chest ailments. Citrullus colocynthis [Figure 8] are used for dog and insect bites, while Myrtus communis is used for scorpion stings. Solanum incanum [Figure 9] is utilized for its antihemorrhagic activity, and Lycium shawii is a traditional detoxifying agent.

Figure 6.

Ficus cordata found in the Jebel Akdhar region. The tree sap is used for relieving and treating bites, boils, and burns.

Figure 7.

Rhazya stricta found in the Dhofar region. Smoke from the dried leaves is inhaled from a pipe for chest ailments.

Figure 8.

Citrulus colocynth found in the Dhofar region. A decoction made from the berries and whole plant is used to treat dog and insect bites.

Figure 9.

Solanum incanum (Mazi) found in the Jebel Akdhar region. Water extract of the roots is useful for the treatment of colds, eye problems, and insect bites.

Conclusions

The paper provides a report on ethnomedicinal uses of some important plants locally available for curing various ailments found in the Jebel Akdhar and Dhofar regions of Oman. The medicinal plants present in these areas are still not fully explored. The curative and palliative effects of some herbs, minerals, and animal parts are well acknowledged among the rural or tribal populations throughout the world, and this information is typically passed on from one generation to another in the folklore community.

In most instances, the traditional medicine acts as the basic level of contact for rural people when they require medical attention. It is important for governments to take urgent steps to introduce the use of traditional medicine to supplement primary health care. Deforestation at the scrub jungles may result in an added damage to the vegetation of the hilly areas and the valleys along with other environmental hazards. The valuable endangered medicinal plants present over these areas will be extinct in the near future if they are not conserved.

Ethnomedicine is considered the origin of all traditional and complementary systems of medicine and even for modern medicine. Ethnomedicine surveys are considered to be useful for the scientific community to provide basic evidence for the therapeutic value and safety of herbal medication.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest. No funding was received for this study.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to all the native medicine men who provided valuable information on herbs and their use.

References

- 1.Saad, Bashar, Azaizeh, Hassan, Said, Omar. Tradition and perspectives of Arab Herbal Medicine: A Review. Advance Acess Publication. eCAM2005; 2 (4), 475-479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Ghazanfar SA, Al-Sabahi MA. Medicinal plants of northern and central Oman. Econ Bot 1993;47:89-98 . 10.1007/BF02862209 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lundin RW. Alfred-Adler's Basic Concepts and Implications. Taylor and Francis. 1998. p. 54. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robert M. Stelmack, Anastasios Stalks. Galen and the humor theory of temperament. Person. Invalid Diff 1991;12(3):255-263 . 10.1016/0191-8869(91)90111-N [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghazanfar SA, Fisher M, eds. Vegetation of the Arabian Peninsula. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oman Animal & Plant Genetic Resources Center. [cited 2015 December 24]. Available from: https://oapgrc.gov.om/plants/SitePages/Plants.aspx.

- 7.Amal Sabra and Sven Walter. Non-Wood Forest Products in the Near East: A Regional and National Overview. Country reports. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, September 2001, p.53.

- 8.Ghazanfar SA. An annotated catalogue of the vascular plants of Oman and their vernacular names. Vol. 2. National Botanic Garden of Belgium, Meise. 1992. p 101. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller AJ, Morris M. Plants of Dhofar (The southern regions of Oman; traditional, economic and medicinal uses) .The office of the adviser for conservation of the environment, Diwan of Royal Court, Sultanate of Oman 1988.

- 10.Douiri LF, Boughdad A, Assobhei O, Moumni M. Chemical composition and biological activity of Allium sativum essential oils against Callosobruchus maculates. IOSR Journal of Environmental Science. Toxicology and Food Technology 2013;3(1):30-36 . 10.9790/2402-0313036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Upali M. Senanayake, Terence H. Lee, Ronald B. H. Wills. Volatile constituents of cinnamon (Cinnamomum zeylanicum) oils. J Agric Food Chem 1978;26(4):822-824 . 10.1021/jf60218a031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaieb K, Hajlaoui H, Zmantar T, Kahla-Nakbi AB, Rouabhia M, Mahdouani K, et al. The chemical composition and biological activity of clove essential oil, Eugenia caryophyllata (Syzigium aromaticum L. Myrtaceae): a short review. Phytother Res 2007. Jun;21(6):501-506. 10.1002/ptr.2124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mimica-Dukić N, Bugarin D, Grbović S, Mitić-Culafić D, Vuković-Gacić B, Orcić D, et al. Essential oil of Myrtus communis L. as a potential antioxidant and antimutagenic agents. Molecules 2010. Apr;15(4):2759-2770. 10.3390/molecules15042759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Camarda L, Dayton T, Di Stefano V, Pitonzo R, Schillaci D. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of some oleogum resin essential oils from Boswellia spp. (Burseraceae). Ann Chim 2007. Sep;97(9):837-844. 10.1002/adic.200790068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shirin Adel P. R and Jamuna Prakash. Chemical composition and antioxidant properties of ginger root (Zingiber officinale). Journal of Medicinal Plants Research 2010;4(24):2674-2679. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Syed Muhammad, Mukarram Shah, Farhat Ullah, Syed Muhammad, Hassan Shah, Mohammad, Zahoor and Abdul Sadiq .Analysis of chemical constituents and antinociceptive potential of essential oil of Teucrium Stocksianum bioss collected from the North West of Pakistan. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine BMC series 2012; 12:244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Ahmadi L, Mirza M, Shahmir F. Essential Oil of Teucrium melissoides Boiss. et Hausskn. ex Boiss. J Essent Oil Res 2002;14(5):355-356 . 10.1080/10412905.2002.9699882 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koksall N, Aslancan H, Sadighazadi S, Kafkas E. Chemical Investigation on Rose damascena Mill. Volatiles; Effects of Storage and Drying Conditions. Acta Sci Pol Hortorum Cultus 2015;14(1):105-114. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grigore A, Ina Paraschiv S. Colceru-Mihul, C. Bubueanu, E. Draghici, M. Ichim. Chemical composition and antioxidant activity of Thymus vulgaris L. volatile oil obtained by two different methods. Rom Biotechnol Lett 2010;15(4):5436-5443. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Afaf M. Weli, Sabha R.K. Al-Hinai, Mohammad M. Hossain, Jamal N. Al-Sabahi. Composition of essential oil of Omani Juniperus excelsa fruit and antimicrobial activity against food borne pathogenic bacteria. Journal of Taibah University for Science 2014;8:225-230 . 10.1016/j.jtusci.2014.04.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turner CE, Elsohly MA, Boeren EG. Constituents of Cannabis sativa L. XVII. A review of the natural constituents. J Nat Prod 1980. Mar-Apr;43(2):169-234. 10.1021/np50008a001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El-Ghonemy AA. Encyclopedia of Medicinal Plants of the United Emirates.1993, 1st Edition, University of UAE. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hussain J, Ali L, Khan AL, Rehman NU, Jabeen F, Kim J-S, et al. Isolation and bioactivities of the flavonoids morin and morin-3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside from Acridocarpus orientalis-A wild Arabian medicinal plant. Molecules 2014;19(11):17763-17772. 10.3390/molecules191117763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vladimir A. Kurkin and Anna A. Shmygareva. The development of new approaches to standardization of Cassia acutifolia leaves. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry 2014;3(3):163-167. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar A, Shukla R, Singh P, Prakash B, Dubey NK. Chemical composition of Ocimum basilicum L. essential oil and its efficacy as a preservative against fungal and aflatoxin contamination of dry fruits. Int J Food Sci Technol 2011;46(9):1840-1846 . 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2011.02690.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mothana RA, Alsaid MS, Al-Musayeib NM. Phytochemical analysis and in vitro antimicrobial and free-radical-scavenging activities of the essential oils from Euryops arabicus and Laggera decurrens. Molecules 2011;16(6):5149-5158. 10.3390/molecules16065149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmad Reza Gohari Soodabeh Saeidnia. A Review on Phytochemistry of Cuminum cyminum seeds and its Standards from Field to Market. Pharmacognosy Journal 2011;3(25):1-5 . 10.5530/pj.2011.25.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aravind. G, Debjit Bhowmik, Duraivel. S, Harish. G. Traditional and Medicinal Uses of Carica papaya. Journal of Medicinal Plants Studies 2013;1(1):7-15. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abebe H, Gebre T, Haile A. Phytochemical Investigation on the Roots of Solanum incanum, Hadiya Zone, Ethiopia. Journal of Medicinal Plants Studies 2014;2(2):83-93. [Google Scholar]

- 30.John K. Mwonjoria, Joseph J. Ngeranwa, Helen N. Kariuki, Charles G. Githinji, Micah N. Sagini, Stanley N. Wambugu. Ethno medicinal, phytochemical and pharmacological aspects of Solanum incanum (Lin.). International Journal of Pharmacology and Toxicology 2014;2(2):17-20. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khaton M. Monira, Shaik M Munan. Review on Datura metel: A Potential Medicinal Plant. Global Journal of Research on Medicinal Plants & Indigenous Medicine 2012;1(4):123-132. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neeraj O. Maheshwari, Ayesha Khan and Balu A. Chopade. Rediscovering the medicinal properties of Datura sp.: A review. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research 2013;7(39):2885-2897. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Herve MP. Poumalea. B, Rodrigue T. Kengapa, Jean Claude Tchouankeua, Felix Keumedjioa, Hartmut Laatschb, and Bonaventure T. Ngadjuia. Pentacyclic Triterpenes and Other Constituents from Ficus cordata (Moraceae). Z. Naturforsch 2008;63b:1335-1338. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Selvaraj G, Kaliamurthy S, Ramkanathan T. Bitter Apple (Citrullus colocynthis): An Overview of Chemical Composition and Biomedical Potentials. Asian J Plant Sci 2010;9(7):394-401 . 10.3923/ajps.2010.394.401 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cosmulescu IT, Achim G, Botu M, Baciu A, Gruia M. Phenolics of Green Husk in Mature Walnut Fruits. Sina Not. Bot. Hort. Agrobot. Cluj 2010;38(1):53-56. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hosseini S, Huseini HF, Larijani B, Mohammad K, Najmizadeh A, Nourijelyani K, et al. The hypoglycemic effect of Juglans regia leaves aqueous extract in diabetic patients: A first human trial. Daru 2014;22(1):19. 10.1186/2008-2231-22-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gilani SA, Kikuchi A, Shinwari ZK, Khattak ZI, Watanabe KN. Phytochemical, pharmacological and ethnobotanical studies of Rhazya stricta Decne. Phytother Res 2007. Apr;21(4):301-307. 10.1002/ptr.2064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Somali MA, Bajneid MA, Al Faimani SS. Chemical composition and characteristics of Moringa peregrina seeds and seed oil. J Am Oil Chem Soc 1984;61(1):85-86 . 10.1007/BF02672051 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moustafa AM, Ahmed SH, Nabil ZI, Hussein AA, Omran MA. Extraction and phytochemical investigation of Calotropis procera: effect of plant extracts on the activity of diverse muscles. Pharm Biol 2010. Oct;48(10):1080-1190. 10.3109/13880200903490513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhong J, Huang Y, Ding W, Wu X, Wan J, Luo H. Chemical constituents of Aloe barbadensis Miller and their inhibitory effects on phosphodiesterase-4D. Fitoterapia 2013. Dec;91:159-165. 10.1016/j.fitote.2013.08.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yao X, Peng Y, Xu LJ, Li L, Wu QL, Xiao PG. Phytochemical and biological studies of Lycium medicinal plants. Chem Biodivers 2011. Jun;8(6):976-1010. 10.1002/cbdv.201000018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shahina A. Ghazanfar. Quantitative and Biogeographic Analysis of the Flora of the Sultanate of Oman. Glob Ecol Biogeogr Lett 1992;2(6):189-195 . 10.2307/2997660 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ulubelen A, Öksüz S, Halfon B, Aynehchi Y, Mabry TJ. Flavonoids from Euphorbia larica, E. virgata, E. chamaesyce and E. magalanta. J Nat Prod 1983;46(4):598-598 . 10.1021/np50028a037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khan ST, Riaz N, Afza N, et al. Studies on the chemical constituents of Prosopis cineraria. J Chem Soc Pak 2006;28(6):619-622. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Al Harthi SS, Mavazhe A, Al Mahroqi H, Khan SA. Quantification of phenolic compounds, evaluation of physicochemical properties and antioxidant activity of four date (Phoenix dactylifera L.) varieties of Oman. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences 2015;10(3):346-352 . 10.1016/j.jtumed.2014.12.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ghazanfar SA. Handbook of Arabian Medicinal Plants CRC Press London 1994, p 144. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Raees MA. Hidayat Hussain, Ahmed Al-Rawahi, Ghulam Abbas, Desmiflavasides A and B: Two new bioactive pregnane glycosides from the sap of Desmidorchis flava. Phytochem Lett 2015;12:153-157 . 10.1016/j.phytol.2015.03.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]