Abstract

The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of crankcase oil on the cellular and functional integrity of rat skin. Thirty (30) rats were randomly grouped into six viz groups A-F. Group A (base-line control) received 2 ml of distilled water. 2.5 %, 5.0 %, 7.5 %, and 10.0 % v/v of the crankcase oil were prepared using unused oil as solvent and 2 ml of the concentrations were topically administered to groups C-F respectively for seven consecutive days. Group B served as positive control and received 2 ml of the unused oil. The rats were sacrificed 24 hours after the last administration, and blood and part of the skin were collected. Alkaline phosphatase (ALP), acid phosphatase (ACP), superoxide dismutase (SOD) and malondialdehyde level in the blood and skin samples collected were evaluated. Elemental analysis of the crankcase oil was also carried out. The result revealed high lead, iron and chromium levels. Blood lead concentration of rats was significantly (P<0.05) high after seven days of administration. ALP level in skin and serum increased significantly (P<0.05) with the concentration of crankcase oil. There was a significant decrease (P<0.05) in skin ACP activity while it increased significantly (P<0.05) in the serum. Similar results were observed in the SOD levels of the serum and the skin. The level increased significantly (P<0.05) in groups D-F when compared with controls. The MDA concentration of both serum and skin were significantly (P<0.05) elevated. This suggests toxic potential of used lubricating oil and its potential predisposition to cancer.

Keywords: crankcase oil, malondialdehyde, cancer, superoxide dismutase

Introduction

Spent engine oil, also known as used mineral-base crankcase oil, is a brown-to-black liquid produced when new engine oil is subjected to high temperature and high mechanical strain (ATSDR, 1997[3]). Spent engine oil is a mixture of several different chemicals (Wang et al., 2000[28]). This includes low and high molecular weight (C15-C20) aliphatic hydrocarbons, aromatic hydrocarbons, polychlorinated biphenyls, chlorodibenzofurans, lubrication additives, decomposition products, heavy metal contaminants such as aluminium, chromium, tin, lead, manganese, silicon, and nickel that comes from engine parts as they wear down (ATSDR, 1997[3]).

Spent engine oil is a common and toxic environmental contaminant not naturally found in the environment (Dominguez-Rosado and Pichtel, 2004[9]). Large amount of used engine oil (crankcase oil) is released into the environment when the motor oil is changed and disposed into the gutter, water drains, open vacant plots and farmland, a common practice by motor mechanics, and generator mechanics (Odjegba and Sadiq, 2002[22]). In addition, the oil is released into the environment from the exhaust system during engine use and due to engine leaks (Anoliefo and Edegbai, 2000[2]; Osubor and Anoliefo, 2003[23]).

Due to its physicochemical properties, the dermal route is an important route of exposure (Christopher et al., 2011[6]) though exposure could also be through inhalation of exhaust fumes. It is known to accumulate carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) during engine running (Carmichael et al., 1990[4]). The toxicity and carcinogenecity of several chemicals, including heavy metals, most aromatic hydrocarbons, have been associated to generation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Carmichael et al. (1992[5]) and Lee et al. (2000[19]) reported an increase in DNA adducts in the tissues of rats topically treated with engine oils. Toxic manifestations of metals, some of which are component of crankcase oil are primarily the result of imbalance between pro-oxidant and antioxidant homeostasis which is termed oxidative stress (Flora et al., 2008[11]). Etiology of most ailments have been associated with oxidative stress (Frei, 2004[12]) including, cancer, anemia, inflammation, schizoprenia and several others associated with tissue dysfunction. The carcinogenesis effect of crankcase oil has been attributed to the fraction of the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) containing more than three rings and may account for about 70 % of the total carcinogenicity. This fraction constitutes only up to 1.14 % by weight of the total oil sample. The content of benzo(a)pyrene may account for 18% of the total carcinogenicity of the used oil (Grimmer et al., 1982[16]). Osubor and Anoliefo (2003[23]) demonstrated that spent engine oil at different concentration interfered with both growth and oxygen uptake of Arachis hypogea seedlings. Studies in mice showed that polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons accumulate in tissue of mice to which crankcase oil was applied topically (Granella and Clonfero, 1991[15]). Antiestrogenic activities have also been reported for crankcase oil, which suggested that its presence in the environment may be of concern for reproductive health (Ssempebwa et al., 2004[26]). The effects of used engine oil are manifested in mechanics and other auto workers who are exposed to used mineral-based crankcase oil as skin problems (rashes), blood damage (anemia), and nervous system derangement (headaches and tremors). However, the effects vary depending on the engine source of the oil. Low doses of the oil inhaled, irritate the nose, throat and eye (Hazlett, 2005[17]). The attitude of auto mechanics in many parts of Nigeria towards the use and disposition of spent engine oil prompted this study to evaluate the toxic effects of the oil on the first line of contacting the skin.

Material and Methods

Source of crankcase oil and reagents

Both fresh and used mineral based oil are products of ABRO industries Incorporation, South Bend, USA. All reagents used were of analytical grades.

Source of experimental animals

A total of thirty (30) female albino rats (Rattus norvegicus) were used. They were obtained from the Animal Holding Unit of the Department of Biochemistry, University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Kwara State, Nigeria. Animal husbandry and experimentation were consistent with Guiding Principles in the use of Animals in Toxicology (Derelanko, 2000[8]).

Elemental analysis of crankcase oil

Elemental analysis for the presence of tale wear metals was performed by Induction Coupled Argon Plasma Spectrometry (ICAP). Metals in oil solution get excited when exposed to argon plasma and emit light at a characteristic wavelength. The amount of light emitted and the wavelength was detected, and through the use of standards, the specific metals were quantified (Pots et al., 1984[24]).

Preparation of different concentrations of crankcase oil and administration

The rats were grouped randomly into six (6) viz groups A-F. Group A (base-line control) received 2 ml of distilled water. 2.5 %, 5.0 %, 7.5 %, and 10.0 % v/v of the crankcase oil were prepared using fresh (unused) oil as solvent and 2 ml of the concentrations were topically administered to groups C-F respectively for seven consecutive days. Group B served as positive control and received 2 ml of the unused oil. The rats were sacrificed 24 hours after the last administration.

Preparation of skin homogenate and serum collection

At the end of the administration period, the rats were sacrificed and a known weight of the skin was taken. The fur on the skin was removed and the skin sliced into pieces, kept in ice-cold 0.25 M sucrose solution (1:5 w/v) and homogenized.

Assay of biochemical parameters

Activity of ALP was determined in the serum and tissue (skin) homogenate by the method of Wright et al. (1972[29]). Activity of ACP was determined in the serum and tissue homogenate by the method of Wright and Plummer (1974[30]). The activity of SOD was determined in the serum and tissue homogenate. Measurement of the thiobarbituric acid reacting substance (TBARS) was used to access lipid peroxidation in the rat skin. This was described by the method of Varshney and Kale (1990[27]).

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean+standard error of mean (S.E.M.). Statistical analysis was done using unpaired student's t-test. Difference was considered to be statistically significant at P<0.05 (Montgomery, 1976[20]).

Results

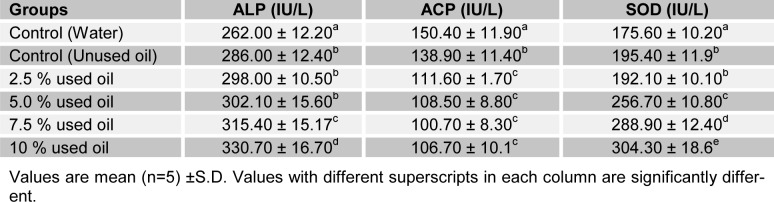

The result of the elemental analysis of crankcase oil is presented in Table 1(Tab. 1). Seven elements were recorded with their concentration ranging from 128.60 µg/ml for lead (Pb) to 32.42 µg/ml for sodium (Na).

Table 1. Elemental composition of crankcase oil.

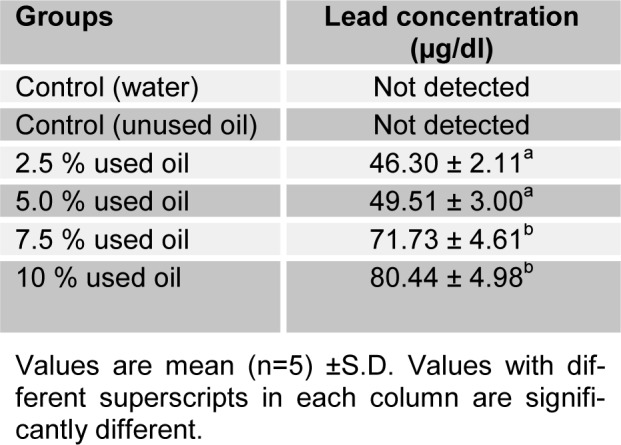

Table 2(Tab. 2) shows the blood lead concentration of the rats after crankcase oil administration on the seventh day. There was significant (P<0.05) increase in blood concentration of lead which is proportional to the administered concentration.

Table 2. Blood lead concentration of rat following the topical administration of crankcase oil for 7 days.

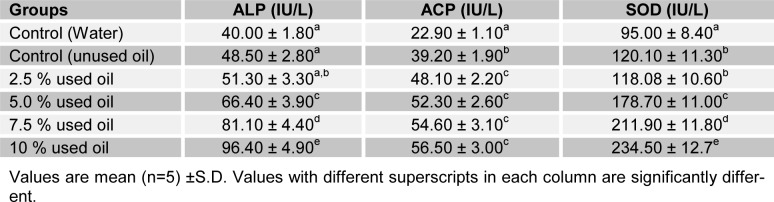

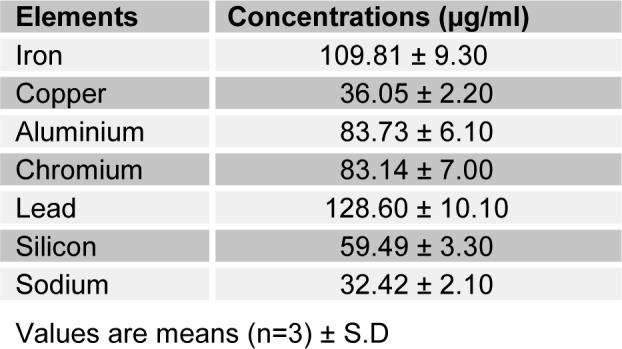

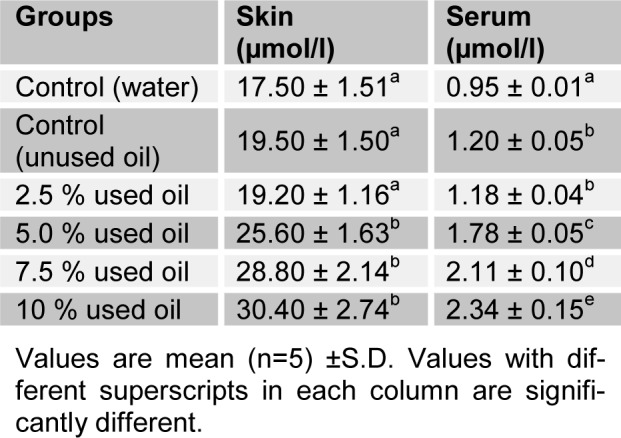

Tables 3(Tab. 3) and 4(Tab. 4) show the effects of the seven-day consecutive administration of crankcase oil on the activities of ALP, ACP and SOD in rat skin and serum. Serum ALP, ACP and SOD activities of test groups were significantly increased (P<0.05) with concentrations when compared with the base-line group. However, there was no significant difference (P>0.05) between serum ALP and SOD at 2.5 % v/v when compared with the positive control. The skin ALP and SOD activities showed a significant increase (P<0.05) in the positive control group when compared with the base-line. However, the activities of the enzymes increased significantly (P<0.05) with increase in concentrations of the mineral based crankcase oil. ACP activity observed in the skin of rats presented an inverse effect of the crankcase oil to skin ALP activity.

Table 3. Selected enzyme activities of rat skin following the topical administration of crankcase oil for 7 days.

Table 4. Selected enzyme activities of rat serum following the topical administration of crankcase oil for 7 days.

The effect of crankcase oil on lipid peroxidation in skin and serum of rats administered varying concentrations of crankcase oil for seven days is presented in Table 5(Tab. 5). The data obtained revealed a significant increase (P<0.05) in MDA concentrations of both tissues studied when compared with the base-line. However, no level of significance was observed at 2.5 % v/v of crankcase oil when compared with the positive control.

Table 5. Effect of crankcase oil on serum and skin malondialdehyde level of rats following 7 days topical administration.

Discussion

The elemental analysis of crankcase oil revealed that it is a rich source of metals (Pots et al., 1984[24]). These metals have various level of toxicity when present above acceptable level in biological systems, although some may serve as cofactor or activators of enzymes (Goyer and Clarkson, 2001[14]). The iron is not of toxicological significance. Lead and chromium have been implicated in carcinogenesis (De Zwart and Slooff, 1987[7]), suggesting that crankcase oil may possess certain degree of deleterious effect. Lead has been recognized as one of the most common and toxic heavy metal contaminants in the environment (Garcia and Corredor, 2004[13]). The skin often absorbs chemical substances on contact and, this could be responsible for the observed increase in blood lead concentration after 7 days of administration of the oil.

Alkaline phosphatase has been employed to assess the integrity of plasma membrane and endoplasmic reticulum (Akanji et al., 1993[1]). Result of ALP activity from this study suggests that the integrity of the membrane system has been compromised by the administration of crankcase oil for seven days. The slight elevation observed in serum ALP activity may be attributed to leakage from tissues into intracellular space due to changes in endothelia permeability, after topical administration for seven days. The significant reduction in skin ACP activity may be due to loss of membrane and cytosolic components including ACP. This was justified by the increase observed in the serum ACP.

The increase in the skin SOD activity observed in groups administered 5.0 %, 7.5 %, and 10.0 % v/v crankcase oil could be as a result of the presence of copper, one of the metallic content of crankcase oil. Copper functions as a cofactor of the enzyme. This is in agreement with the fact that copper alongside zinc, plays a catalytic role in SOD activity (Raha and Robinson, 2000[25]). The increase in serum SOD activity is suggestive of a possible damage to tissue cell plasma membrane due to administration of the crankcase oil thus, leading to the escape of membrane components into extracellular fluid (Akanji et al., 1993[1]). Superoxide dismutase (SOD) constitutes the first line of defence against reactive oxygen species. Superoxide is produced at any location where electron transport is present hence O2 activation occurs in different compartments of the cell including mitochondria, chloroplasts, cytosol, etc. (Elstner, 1991[10]). SOD activity has been reported to increase under oxidative stress, in response to external stimuli. Oxidative stress induced mechanism is thus the likely mode of actions of the toxic components of the crankcase oil. Genetic polymorphism of SOD has been linked to oxidative DNA damage and as a result increases risk of cancer (Khan et al., 2010[18]). Malondialdehyde is a major product of lipid peroxidation. During oxidative stress, MDA and other aldehydes are formed in biological systems. Higher level of MDA in the skin suggests a higher degree of lipid peroxidation. This may have resulted from accumulation of free radicals causing oxidative stress in vivo (Murray et al., 1999[21]). Oxidative stress has been linked to tumorigenesis and carcinogenesis. Also, the elevation observed in the serum MDA concentration may be due to plasma membrane derangement thus leading to leakage from the skin into the extracellular fluid.

In conclusion, this study has provided additional information that crankcase oil could have adverse effects on the skin with repeated exposures. This is because exposure to crankcase oil has been found to be associated with increased lipid peroxidation in rat skin - a consequence of oxidative stress. The observed significant increase in the activities of enzymes studied in the serum further revealed that skin damage might occur when exposed to crankcase oil. Thus revealing that repeated and continuous contact of the skin with the oil may be deleterious to human health.

References

- 1.Akanji MA, Olagoke OA, Oloyede OB. Effect of chronic consumption of metabiosulphate on the integrity of rat kidney cellular system. Toxicology. 1993;81:173–179. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(93)90010-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anoliefo GO, Edegbai BO. Effect of spent engine oil as a soil contaminant on the growth of two eggplant species;Solanum melongena L. and S. incanum. J Agric Forestry Fish. 2000;1:21–25. [Google Scholar]

- 3.ATSDR (Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry) Toxicological Profile for mineral base crankcase oil. Atlanta, GA: Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service Press,; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carmichael PL, Jacob J, Grimmer G, Phillips DH. Analysis of the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon content of petrol and diesel engine lubricating oils and determination of DNA adducts in topically treated mice by 32P-postlabelling. Carcinogenesis. 1990;11:2025–2032. doi: 10.1093/carcin/11.11.2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carmichael PL, Ni Shé M, Hewer A, Jacob J, Grimmer G, Phillips DH. DNA adduct formation in mice following treatment with used engine oil and identification of some of the major adducts by 32P-postlabelling. Cancer Lett. 1992;64:137–144. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(92)90074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christopher Y, Van Tongeren M, Urbanus J, Cherrie JW. An assessment of dermal exposure to heavy fuel oil (HFO) in occupational settings. Ann Occup Hyg. 2011;55:319–328. doi: 10.1093/annhyg/mer002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Zwart D, Slooff WC. Toxicity of mixtures of heavy metals and petrochemicals to Xenopus laevis. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 1987;38:345–351. doi: 10.1007/BF01606685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Derelanko MJ. Guiding principles in the use of animals in toxicology. In: Derelanko MJ, editor. The toxicologist’s pocket handbook. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2000. pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dominguez-Rosado RE, Pichtel J. Phytoremediation of soil contaminated with used motor oil: Enhanced microbial activities from laboratory and growth chamber studies. Environ Eng Sci. 2004;2:157–168. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elstner EF. Mechanisms of oxygen activation in different compartments of plant cells. In: Pell EJ, Steffen KL, editors. Active oxygen/oxidative stress and plant metabolism. Rockeville, MD: American Society of Plant Physiologists; 1991. pp. 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flora SJ, Mittal M, Mehta A. Heavy metal induced oxidative stress and its possible reversal by chelation therapy. Indian J Med Res. 2008;128:501–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frei B. Efficacy of dietary antioxidants to prevent oxidative damage and inhibit chronic disease. J Nutr. 2004;134:3196S–3198S. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.11.3196S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia TA, Corredor L. Biochemical changes in the kidneys after perinatal intoxication with lead and/or cadmium and their antagonistic effects when co-administered. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2004;57:118–189. doi: 10.1016/S0147-6513(03)00063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goyer RA, Clarkson TM. Toxic effects of metals. In: Klaassen CD, editor. Casarett & Doull’s toxicology. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001. pp. 811–868. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Granella M, Clonfero E. The mutagenic activity and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon content of mineral oils. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1991;63:149–153. doi: 10.1007/BF00379080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grimmer G, Dettbarn G, Brune H, Deutsch-Wenzel R, Misfeld J. Quantification of the carcinogenic effect of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in used engine oil by topical application onto the skin of mice. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1982;50:95–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00432496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hazlett JM. Report for the Calumet Air Monitoring Project. Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality, Office of Environmental Assessment; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan MA, Tania M, Zhang D, Chen H. Antioxidant enzymes and cancer. Chin J Cancer Res. 2010;22(2):87–92. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee JH, Roh JH, Burks D, Warshawsky D, Talaska G. Skin cleaning with kerosene facilitates passage of carcinogens to the lungs of animals treated with used gasoline engine oil. Appl Occup Environ Hyg. 2000;15:362–369. doi: 10.1080/104732200301485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montgomery DC. Design and analysis of experiment. New York: Wiley; 1976. pp. 48–50. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murray RK, Granner DK, Mayes PA, Rodwell VW. Enzymes: regulation of activities. In: Murray RK, Granner DK, Mayes PA, Rodwell VW, editors. Harpers’s illustrated biochemistry. 27th. (pp ). New York: McGraw-Hill; 1999. pp. 89–91. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Odjegba VJ, Sadiq AO. Effect of spent engine oil on the growth parameters, chlorophyll and protein levels of Amaranthus hybridus L. The Environmentalist. 2002;22:23–28. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Osubor CC, Anoliefo GO. Inhibitory effect of spent lubrication oil on the growth and respiratory function of Arachis hypogea L. Benin Sci Dig. 2003;1:73–79. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pots PJ, Webb PC, Watson JS. Energy dispersive x-ray fluorescence analysis of silicate rock for major and trace element. X-Ray Spectrom. 1984;13:2–15. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raha S, Robinson BH. Enzyme activity and tissue condition. J Clin Pathol. 2000;24:49–51. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ssempebwa J, Carpenter D, Yilmaz B, DeCaprio A, O'Hehir D, Arcaro K. Waste crankcase oil: an environmental contaminant with potential to modulate estrogenic responses. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2004;67:1081–1094. doi: 10.1080/15287390490452308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Varshney R, Kale RK. Effects of calmodulin antagonist on radiation induced lipid peroxidation in microsome. Int J Radiat Biol. 1990;58:733–743. doi: 10.1080/09553009014552121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J, Jia CR, Wong CK, Wong PK. Characterization of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon created in lubricating oils. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2000;120:381–396. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wright PJ, Leathwood PD, Plummer DT. Enzymes in rat urine. Alkaline phosphatase. Enzymologia. 1972;42:317–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wright PJ, Plummer DT. The use of urinary enzyme measurements to detect renal damage caused by nephrotoxin compounds. Biochem Pharmacol. 1974;23:65–73. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(74)90314-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]