Abstract

-

➤

It is important to carefully select the most appropriate combination of scaffold, signals, and cell types when designing tissue engineering approaches for an orthopaedic pathology.

-

➤

Although clinical studies in which the tissue engineering paradigm has been applied in the treatment of orthopaedic diseases are limited in number, examining them can yield important lessons.

-

➤

While there is a rapid rate of new discoveries in the basic sciences, substantial regulatory, economic, and clinical issues must be overcome with more consistency to translate a greater number of technologies from the laboratory to the operating room.

The field of orthopaedics has a long history of embracing new technologies. From total joint replacement to the use of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 (rhBMP-2), orthopaedic surgeons and biomedical engineers have worked together to create novel strategies to repair and/or replace damaged tissues. Tissue engineering, the science of generating living tissues, holds promise for treating human disease. Specific to the field of orthopaedics, tissue engineering strategies are being investigated for a number of challenging musculoskeletal pathologies, including fracture nonunion, osteonecrosis, and osteochondral defects.

While exciting developments are being investigated in the laboratory and in preclinical animal models1,2, the majority of tissue engineering-based therapies may not be translated into the clinic3-5. The primary goals of this review were (1) to provide an overview of tissue engineering as relevant to orthopaedic surgery; (2) to review how these principles are being applied to treat orthopaedic diseases today, with examples from current studies; and (3) to discuss future directions and challenges for continuing to translate tissue engineering strategies from the laboratory to the operating room.

Principles of Orthopaedic Tissue Engineering

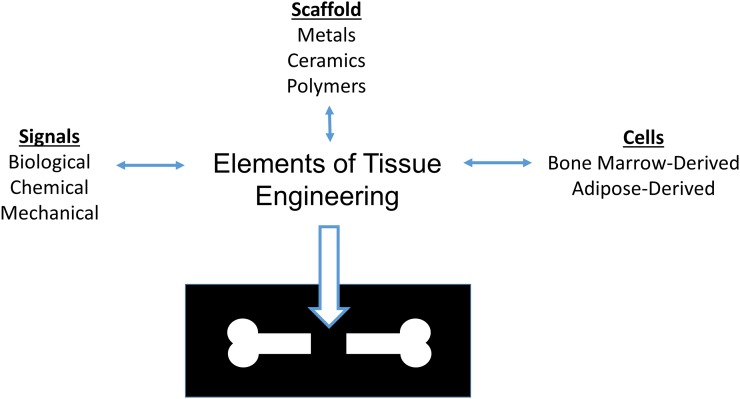

Fundamentally, the tissue engineering paradigm consists of scaffolds, signals, and cells (Fig. 1). These 3 elements can be combined or used independently to attempt to generate tissues in a limitless number of arrangements. However, with an increasing complexity of design, there are greater challenges to translation6. For example, receiving regulatory approval for an acellular scaffold requires substantially less time and fewer resources than does a drug-eluting scaffold that has been pre-seeded with stem cells. In this section, these 3 fundamental elements of orthopaedic tissue engineering are reviewed.

Fig. 1.

The orthopaedic tissue engineering paradigm.

Scaffolds

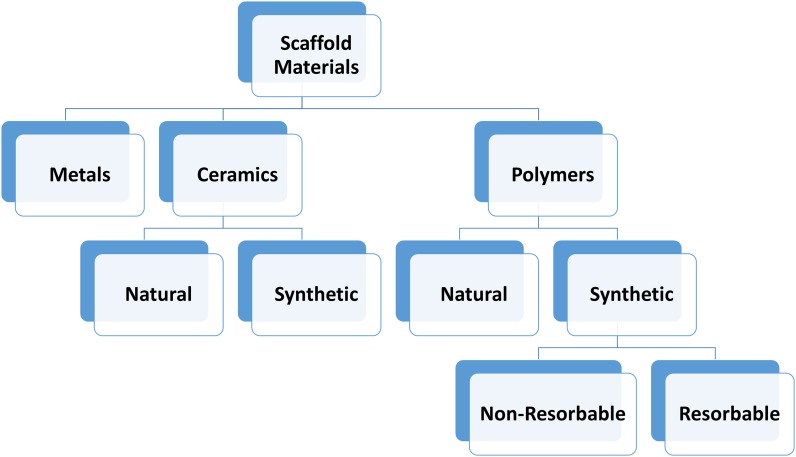

Tissue engineering scaffolds are cytocompatible biomaterials that cells can adhere to and/or replace with extracellular matrix to produce native tissues. Scaffolds can be as simple as morselized autologous bone or as complex as injectable, thermally responsive synthetic hydrogels capable of mineralizing in situ7. On the basis of material composition, scaffolds can be divided into 3 basic classes: metals, ceramics, and polymers (Fig. 2). Scaffolds can be further divided by their source (naturally derived versus synthetically fabricated) and ability to degrade (nonresorbable versus resorbable). Although they are stable, nonresorbable scaffolds and delivery systems cannot be replaced by native tissues and may elicit a chronic foreign-body reaction detrimental to tissue healing. Naturally derived scaffolds (such as those made from collagen, chitosan, and hyaluronan) are generally all resorbable in situ and often already possess adhesion ligands for cellular attachment. However, naturally derived scaffolds typically have a narrow range of available physical properties, such as mechanical strength and degradation rate. Synthetic scaffolds can be tuned to have a wide variety of properties by altering synthesis components and parameters. Not all synthetic scaffolds are biodegradable, and cell adhesion motifs may need to be added in order to promote biocompatibility. Different scaffold materials can also be combined to create composite scaffolds that have novel properties not observed in either material used alone8.

Fig. 2.

Overview of the classes of scaffolds.

Many considerations are important in selecting a scaffold. For orthopaedics, mechanical properties and durability are paramount to a successful device. While a ceramic scaffold may have appropriate compressive strength in a femoral nonunion defect, its high stiffness and weak tensile properties would be inappropriate for use in a cartilage defect or repairing a rotator cuff. Another important factor to consider is the compatibility of the rate of scaffold resorption with the rate of native tissue replacement. If a scaffold resorbs too rapidly, it may not be able to support the growth of new tissues. If a scaffold resorbs too slowly, it may not fully integrate with surrounding tissues and may pose risks associated with chronic foreign bodies. The effect of the scaffold on native cells may also be important in choosing a material. Scaffolds may be osteoconductive (i.e., permit the growth of bone, such as the calcium sulfates9) or osteoinductive (i.e., actively promote bone growth in a defect that otherwise would not heal, such as demineralized bone matrix9). As scaffolds with carefully selected properties can recruit native stem cells and direct their differentiation into the proper tissue of choice, implantation of acellular scaffolds may become the gold standard in tissue engineering-based orthopaedic products10. Last, depending on the intended application, scaffolds may require gradient-based rather than isotropic properties, such as in the functional repair of osteochondral defects and tendon or ligament-to-bone insertions11,12.

Signals

In the tissue engineering paradigm, signals are internally or externally derived environmental factors that can influence the regeneration of tissues. As in the case of scaffolds, these signals can be further broken down into subcategories including biological, chemical, mechanical, and electrical cues. In orthopaedics, the most commonly utilized biological signal is rhBMP-2, a potent osteogenic growth factor. Clinical products containing rhBMP-2 have been approved for specific applications by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Table I)13. However, it appears that rhBMP-2 is associated with both a substantially greater risk of adverse events as well as a higher severity of adverse events than originally reported14, and there remain concerns about the use of growth factors in light of their association with malignancies such as osteosarcoma15,16. Another common source of biological signals used in tissue engineering strategies is platelet rich plasma (PRP) and its different variants17. PRP is a combination of blood components that are isolated and concentrated (typically by centrifugation). While use of PRP is appealing because of the ease of autologous obtainment, its actual efficacy in the regeneration of musculoskeletal tissues currently remains uncertain18. In addition to exogenous delivery, biological factors can also be delivered by cells through genetic engineering techniques, although there is some controversy over safety for in situ approaches19,20. Finally, co-delivery of combinations of biological cues, such as osteogenic and angiogenic growth factors21,22, has resulted in enhanced tissue regeneration in animal models but has not been translated to clinical trials, perhaps because of concerns of carcinogenicity associated with the upregulation of angiogenic factors23,24.

TABLE I.

Approved Indications for rhBMP-2-Based Devices

| Application | Disease and/or Procedure | Device |

| Oral maxillofacial | Sinus augmentations | rhBMP-2 in a resorbable collagen sponge |

| Oral maxillofacial | Localized alveolar ridge augmentations for defects associated with extraction sockets | rhBMP-2 in a resorbable collagen sponge |

| Spine | Degenerative disc disease (at 1 level from L2 to S1) | rhBMP-2 in a resorbable collagen sponge within a metallic spinal fusion cage |

| Trauma | Acute open tibial fractures (stabilized by intramedullary nail fixation) | rhBMP-2 in a resorbable collagen sponge |

Chemical cues may promote healing by influencing the inflammatory pathway (such as statins25) or by directly acting on cells (such as site-specific bisphosphonate therapy26). Locally delivered small molecules for bone tissue engineering is a growing area of interest in the regenerative medicine community27. Antibiotics are another example of chemical cues often delivered in conjunction with tissue engineering strategies. In an infected orthopaedic defect, encapsulating antibiotics for local drug delivery into the scaffold may be required to stimulate healing28.

Mechanical cues have long been used to stimulate bone formation, such as in distraction osteogenesis. Recent studies have demonstrated that passive mechanical signals provided by scaffolds (such as substrate stiffness, roughness, and porosity) can influence the differentiation of stem cells toward specific lineages29,30. Electrical cues have been demonstrated to be important in generating functional skeletal muscle tissue as well as innervation of neotissues31,32, but have not been explored as thoroughly relative to other cellular signals for orthopaedic tissue engineering applications.

Cells

In order to create living tissues, as well as integrate living engineered tissue with native host tissues, cells must be present. Cells can be recruited into an implanted scaffold by methods such as the release of chemokines33, attachment of cell ligands to the scaffold34, or osteoconduction or osteoinduction, or scaffolds containing cells can be implanted into a defect. Unlike in other tissue engineering fields, there is little controversy regarding stem cell type in orthopaedic tissue engineering. By far, the most commonly utilized cell type is the mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) (Table II)35. Depending on their environment, MSCs have the ability to differentiate into osteoblasts, chondroblasts, myoblasts, and tenocytes as well as other adult cells36. Compared with other stem cell populations, such as neural progenitor cells, MSCs are relatively easy to harvest from an autologous host. However, the optimal source for MSCs is controversial at this time. The current gold standard is MSCs harvested from bone marrow aspirate; however, adipose-derived MSCs are gaining more traction in the field because of their increased availability, lower harvesting costs, and ease of expansion37. Amniotic fluid-derived MSCs are another intriguing source that has recently been shown to be capable of osteogenesis and chondrogenesis in small animal models38,39. Other sources of MSCs include skin40, periosteum41, and umbilical cord blood42. However, ease of collection should not be the only consideration in MSC harvesting. MSCs from different sources have different potential for differentiation36,43,44 and may affect the quality of tissue repair45.

TABLE II.

Criteria for Defining a Cell Population as MSCs According to the International Society for Cellular Therapy35*

| Criteria | Definition |

| Culture conditions | MSCs must be expandable as well as plastic-adherent under normal culture conditions |

| Trilineage potential | MSCs must be able to differentiate into osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes in vitro as demonstrated by histological staining |

| Positive surface markers | MSCs must possess CD73, CD90, and CD105 surface markers (≥95% positive) |

| Negative surface markers | MSCs must lack CD14 or CD11b, CD19 or CD79α, CD34, CD45, and HLA-DR surface markers (<2% positive) |

Cell populations not meeting these rigorous criteria but capable of differentiating into musculoskeletal cells should be referred to as “connective tissue progenitor” cells. HLA = human leukocyte antigen.

Initially, it was believed that the primary mechanism of action of implanted MSCs within an orthopaedic defect was structural. It was assumed that the implanted MSCs themselves would proliferate, differentiate, and generate the extracellular matrix required to repair the defect. However, recent studies have revealed the tremendous pleiotropic effects of MSCs. Beyond their ability to terminally differentiate into adult musculoskeletal cells, MSCs secrete a variety of cytokines and modulate inflammatory and immune response pathways46. Because of these immunomodulatory effects, implantation of allogeneic MSCs carries minimal risk of rejection by the host and commercially available MSCs are being explored in a number of clinical trials for a multitude of autoimmune diseases46-48. Despite all of these positive attributes, there is still concern over potential long-term side effects from MSC transplantation and the lack of comparability in demonstrating efficacy between clinical trials49. Patients enrolled in clinical trials are carefully monitored; a recent report has demonstrated that no infection or tumor had developed in patients treated with MSCs for osteoarthritis at 11 years of follow-up50.

The need to implant living cells into an orthopaedic defect for repair is situational. From a product development and regulatory standpoint, acellular strategies present advantages over cell-containing products10, which carry a potential risk of rejection or disease transmission, have heterogeneous cell populations, etc. For example, it is clear that rhBMP-2 combined with a collagen scaffold has ample regenerative capacity for spinal fusion without the addition of any exogenous MSCs51. However, for complex diseases such as osteonecrosis, the pleiotropic and immunomodulatory capacities of MSCs may be required for treatment52.

Orthopaedic Tissue Engineering Elements Applied in Recent Clinical Experiences

While it is outside the scope of this work to review all of the exciting developments in the field, a series of recent clinical studies (2011 to the present) have been chosen arbitrarily to highlight how the previously discussed elements of tissue engineering have been applied to treat orthopaedic diseases53-63. Examples were chosen from the following areas: fracture nonunion, osteonecrosis, and chondral and osteochondral defects. For easy reference, these examples have been compiled in Table III. We recommend several excellent recent reviews on these topics by Panteli et al., Mont et al., and Nicolini et al. for a more complete discussion on disease pathophysiology64-66.

TABLE III.

Recent Examples of Orthopaedic Tissue Engineering Strategies Applied in Human Disease (2011-Present) and Corresponding Elements of the Tissue Engineering Paradigm

| Study | No. of Patients | Elements | Summary |

| Nonunion | |||

| Kuroda et al.53 (2014) | 7 | Scaffold and cells | Bone marrow-derived hematopoietic stem cells were delivered on atelocollagen in femoral and tibial nonunion defects |

| Calori et al.54 (2013) | 52 | Scaffold, signals, and cells | Retrospective review of patients treated at a single center; patients were divided into monotherapy (treated with scaffold, cells, or signals) or polytherapy (treated with all 3) |

| Desai et al.55 (2015) | 49 | Scaffold, signals, and cells | Bone marrow aspirate MSCs were delivered with demineralized bone matrix or rhBMP-2 |

| Osteonecrosis | |||

| Hwang et al.56 (2011) | 43 | Cells | Autologous bone marrow-derived MSCs implanted alone |

| Aarvold et al.57 (2013) | 4 | Scaffold and cells | Autologous bone marrow-derived MSCs implanted with morselized allograft |

| Aoyama et al.58 (2014) | 10 | Scaffold and cells | Autologous bone marrow-derived MSCs implanted with β-tricalcium phosphate scaffold in combination with vascularized bone graft |

| Chondral and osteochondral defects | |||

| Jo et al.59 (2014) | 9 | Cells | Autologous adipose-derived MSCs injected into osteoarthritic knees at different dosages |

| Ha et al.60 (2015) | 27 | Signals and cells | Injection of allogeneic chondrocytes engineered to express TGF-β1 |

| Delcogliano et al.61 (2014) | 19 | Scaffold | Acellular collagen-hydroxyapatite scaffold |

| Kon et al.62,63 (2011 and 2014) | 27 | Scaffold | Acellular gradient-based collagen-hydroxyapatite scaffold |

Fracture Nonunion

While there is currently no standardized definition, fracture nonunion has been defined by the FDA and others as incomplete healing at 9 months after injury and the absence of healing progression over the following 3 consecutive months64. Despite advances in surgical techniques, fracture nonunions continue to present clinical challenges67. As disrupted vascularity is one of the major contributors to nonunion68, strategies to enhance angiogenesis, including delivery of hematopoietic stem cells, are being explored. In one study, autologous bone marrow-derived hematopoietic stem cells were delivered on an atelocollagen scaffold into tibial and femoral nonunion defects in 7 patients53. This combination of cells and scaffold resulted in fracture-healing in 5 (71%) of 7 patients at 12 weeks. While there was no control arm, the threshold of healing achieved in the historical outcome of the standard of care was 18% (2 of 11 patients).

In a retrospective review of 52 patients treated for forearm nonunion defects at a single center, patients were categorized as being treated with a single tissue engineering element (MSCs, a scaffold, or BMP, i.e., “monotherapy”) or with all 3 elements of the tissue engineering paradigm (“polytherapy”)54. It is not clear if a standard concentration of MSCs was used among the patients. With a minimum follow-up time of 1 year, patients receiving all 3 elements had significantly improved radiographic healing, clinical success criteria, and rapidity of healing compared with patients treated with monotherapy. While that study lends support to the synergistic nature of combining cells, scaffolds, and signals to treat severe orthopaedic defects, a randomized prospective study would have provided stronger evidence by minimizing bias.

To better compare combinations of cells, scaffolds, and signals in treating nonunion defects, a nonrandomized retrospective-prospective cohort study with 46 patients compared patients treated with bone marrow-derived stem cells with a scaffold (demineralized bone matrix) or rhBMP-255. A third group of 3 patients was treated with both scaffold and signal but was underpowered for statistical analysis. In that study, a greater percentage of patients treated with cells and scaffolds demonstrated healing compared with those who had treatment with cells and rhBMP-2 (86.4% versus 70.8%; p = 0.033). The authors postulated that because the demineralized bone matrix scaffold is osteoconductive and can recruit osteoprogenitor cells, it may be more effective than a single growth factor. Interestingly, all 3 patients treated with polytherapy (cells, signals, and scaffold) in that study demonstrated healing.

Osteonecrosis

Given their necrotic nature, the lesions associated with osteonecrosis have poor innate regenerative capacity with few or no viable MSCs. In addition, it has been reported that, in corticosteroid-induced osteonecrosis, there is a global decrease in available MSCs52. In theory, MSC therapy may be promising, given the immunomodulatory properties of MSCs as well as their ability to secrete angiogenic growth factors and recruit local vasculature52. Therefore, the delivery of MSCs (alone or in a scaffold) has been the goal of at least 18 published reports, according to Mont et al., in 201565. Examples of clinical successes with MSC therapy alone were reported in recent meta-analyses, but it was noted that comparisons between studies were difficult because of variations in the numbers of MSCs delivered52,65.

As implantation with scaffolds has been demonstrated to improve MSC viability in animal models69, a logical application of the tissue engineering paradigm is to pair implanted MSCs with a scaffold to ensure consistent MSC dosage as well as to support proliferation. In a recent clinical study of 5 femoral heads in 4 patients, autologous bone marrow-derived MSCs were seeded onto morselized allogeneic bone as scaffold and were implanted in the defect after core decompression57. Unfortunately, in the patient who received treatment bilaterally, disease progressed in both femoral heads, leading to bilateral total hip replacement (after 13 and 19 months, respectively). However, this presented an opportunity to harvest the bone to analyze the treatment with radiographic, histological, and mechanical testing. Microcomputed tomography revealed that the treated zone was greater in opacity than trabecular bone. The tissue in the treated zone was histologically and mechanically indistinguishable from the patient’s healthy trabecular bone. The other 3 patients had no more disease progression after treatment (22 to 44 months of follow-up). As the authors noted, “Further clinical trials are necessary, including comparison to concurrent therapies,” before the full efficacy of the treatment compared with the current state of the art can be determined. However, the study as it stands represents a unique opportunity in which repair by tissue engineering elements could be evaluated with precision, including by mechanical testing, in treated human tissues.

In a similar study in which cells and scaffolds were utilized in disease treatment, 10 patients with osteonecrosis were treated with vascularized bone grafts augmented with autologous bone marrow-derived MSCs seeded on a β-tricalcium phosphate scaffold58. At 2 years of follow-up, 9 patients had completed the protocol and 7 had no further disease progression. (One patient had been excluded because hip surgery had been performed bilaterally before the end of the follow-up period.) In the 2 patients who had disease progression, the authors postulated that “an imbalance between bone resorption and formation” may have contributed to the cystic lesions observed in their femoral heads 1 year after surgery. Given the degradation rate of β-tricalcium phosphate (weeks to months) and the low innate regenerative potential of the femoral head in osteonecrosis, a mismatch in the rate of scaffold degradation and native tissue regeneration may have resulted in collapse of the lesion. While a prospective randomized study is required for conclusive evidence on treatment superiority, these studies in sum demonstrate how selection of scaffold properties may impact the clinical outcome.

Chondral and Osteochondral Defects

Perhaps because of the tremendous clinical need for new therapies, there have been many recent studies involving tissue engineering strategies for the treatment of cartilage-based defects. Cell monotherapy for the treatment of cartilage defects is more common than in other orthopaedic pathologies. In fact, autologous expanded chondrocytes are part of a product regulated by the FDA and approved for the repair of symptomatic cartilage defects (Carticel; Vericel)70. Despite the popularity of these monotherapies, the optimal amount of MSCs required for efficacy is unclear. In a recent study, autologous adipose-derived MSCs in 3 different doses were injected without scaffold or exogenous signals into osteoarthritic knees in 18 patients59. While no patient experienced treatment-related adverse events, the effects of dose are more difficult to ascertain as the low and medium dosage groups had only 3 patients each. However, patients in the high dosage group demonstrated significantly improved clinical, radiographic, and arthroscopic measurements compared with baseline, and these improvements were not reflected in the low and medium dosage groups.

Increasing in complexity, allogeneic chondrocytes that have been genetically modified to express transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-β1) by retroviral modification ex vivo were injected at 2 different concentrations in 27 patients with osteoarthritis60. While the 2 groups did not show significant differences in healing compared with one another, both groups demonstrated significantly improved clinical scores (including reduced pain and stiffness and increased physical function) compared with baseline values. Given the public perception of genetic engineering20, perhaps the most important findings of the study were the absence of serious adverse events and no evidence of global changes in TGF-β1 expression in patients or the appearance of the retroviral vector DNA in patient samples. This recent work demonstrates that cells can be programmed to deliver signals themselves to mitigate disease in human patients, rather than requiring exogenous delivery of the signals through non-living vehicles such as collagen sponges or microparticles.

Acellular scaffolds for the repair of cartilage defects have also been investigated in the past 5 years61-63,71. For osteochondral defects, acellular composite scaffolds consisting of both bone-like and cartilage-like layers have recently been investigated in human patients. In one of these studies, a commercially available acellular scaffold consisting of a top layer of equine-derived type-I collagen and a bottom layer consisting of magnesium-enriched hydroxyapatite was used to treat osteochondral defects in 19 patients with 2 years of follow-up61. Patients exhibited a significantly improved subjective score at the 1-year follow-up; the score improved further, but not significantly, at the 2-year follow-up. While treatment was satisfactory in these patients, as a nonrandomized study with no control group, it is difficult to comment on efficacy. Another similar composite scaffold, constructed using collagen and hydroxyapatite nanoparticles in a gradient-based fashion, was implemented in 27 patients62,63. Again, patients showed significant improvement compared with baseline values at both 2 and 5 years following treatment, which is historically not the case with osteochondral defects. While this improvement could be due to the gradient-based nature of the acellular scaffold, without a nongradient-based control, it is difficult to draw any definitive conclusions regarding the effects of acellular gradient-based scaffolds on the treatment of osteochondral defects in human disease.

Future Directions and Challenges

Although the future for orthopaedic tissue engineering is bright, there is much work to be done. While the small number of clinical studies reviewed in the present work may not necessarily be a representative sample of the field as a whole, they demonstrate that small patient numbers, lack of randomization, and absence of control groups consisting of current clinical treatment standards can make it difficult to determine the efficacy of the various elements of the tissue engineering paradigm in orthopaedics. In addition, a dearth of standardization in clinical protocols makes it difficult to compare results across existing studies. Even in cases of excellent clinical results, regulatory hurdles and the need for large amounts of capital for product translation contribute to the considerable barriers in guiding more tissue engineering-based technologies into the operating room3,4.

Our understanding of the interactions between materials and biological tissues continues to grow. New manufacturing techniques, such as the advent of high-resolution bioprinting72,73, are allowing for the rapid creation of personalized devices to an extent that was not previously possible. Infections, which often plagued implantation of foreign materials like scaffolds, are being mitigated by advances in anti-infective strategies such as biofilm-repulsing surfaces and antibiotic-delivering materials74. Synthetic biology and genetic engineering techniques are being utilized to reprogram cells to optimize healing60. Ultimately, products such as INFUSE (Medtronic) and Carticel have demonstrated that the field of orthopaedics is willing to adopt tissue engineering strategies into clinical practice. Hopefully, product development will catch up with these breakthroughs in fundamental knowledge as tissue engineers and clinicians alike better understand how to tackle the hurdles surrounding translation.

In conclusion, the goals of this work were to introduce the basic tenets of orthopaedic tissue engineering and to use current examples in the field to discuss how these elements can aid in treating human disease. While the field is advancing at an exponential rate and new discoveries are constantly being made, these fundamental principles will remain relevant. When designing a tissue engineering-based approach to an orthopaedic pathology, one must consider the appropriate scaffold, cell type, and source, and whether the inclusion of exogenous signals is necessary. In the past, the benchmark for successful treatment of conditions such as osteoarthritis was lack of disease progression. With the new therapies inspired by tissue engineering, the new benchmark may be the absence of disease.

Footnotes

Investigation performed at the Department of Bioengineering, Rice University, Houston, Texas

Disclosure: This work was supported by the Army, Navy, National Institutes of Health, Air Force, Veterans Affairs, and Health Affairs to support the AFIRM II effort, under Award No. W81XWH-14-2-0004. This work was also supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH R01 AR068073). The Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest forms are provided with the online version of the article.

Disclaimer: Opinions, interpretations, conclusions and recommendations are those of the authors and are not necessarily endorsed by the Department of Defense.

References

- 1.Henkel J, Woodruff MA, Epari DR, Steck R, Glatt V, Dickinson IC, Choong PF, Schuetz MA, Hutmacher DW. Bone regeneration based on tissue engineering conceptions—a 21st century perspective. Bone Res. 2013. September;1(3):216-48. Epub 2013 Sep 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hogan MV, Walker GN, Cui LR, Fu FH, Huard J. The role of stem cells and tissue engineering in orthopaedic sports medicine: current evidence and future directions. Arthroscopy. 2015. May;31(5):1017-21. Epub 2015 Feb 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davies BM, Rikabi S, French A, Pinedo-Villanueva R, Morrey ME, Wartolowska K, Judge A, MacLaren RE, Mathur A, Williams DJ, Wall I, Birchall M, Reeve B, Atala A, Barker RW, Cui Z, Furniss D, Bure K, Snyder EY, Karp JM, Price A, Carr A, Brindley DA. Quantitative assessment of barriers to the clinical development and adoption of cellular therapies: a pilot study. J Tissue Eng. 2014;5:2041731414551764. Epub 2014 Sep 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Madry H, Alini M, Stoddart MJ, Evans C, Miclau T, Steiner S. Barriers and strategies for the clinical translation of advanced orthopaedic tissue engineering protocols. Eur Cell Mater. 2014;27:17-21; discussion 21. Epub 2014 May 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niemansburg SL, van Delden JJ, Oner FC, Dhert WJ, Bredenoord AL. Ethical implications of regenerative medicine in orthopedics: an empirical study with surgeons and scientists in the field. Spine J. 2014. June 1;14(6):1029-35. Epub 2013 Nov 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atala A, Kasper FK, Mikos AG. Engineering complex tissues. Sci Transl Med. 2012. November 14;4(160):60rv12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vo TN, Shah SR, Lu S, Tatara AM, Lee EJ, Roh TT, Tabata Y, Mikos AG. Injectable dual-gelling cell-laden composite hydrogels for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2016. March;83:1-11. Epub 2015 Dec 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santoro M, Tatara AM, Mikos AG. Gelatin carriers for drug and cell delivery in tissue engineering. J Control Release. 2014. September 28;190:210-8. Epub 2014 Apr 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenwald AS, Boden SD, Goldberg VM, Khan Y, Laurencin CT, Rosier RN; American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. The Committee on Biological Implants. Bone-graft substitutes: facts, fictions, and applications. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(Suppl 2 Pt 2):98-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schüttler KF, Efe T. Tissue regeneration in orthopedic surgery—do we need cells? Technol Health Care. 2015;23(4):403-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohan N, Dormer NH, Caldwell KL, Key VH, Berkland CJ, Detamore MS. Continuous gradients of material composition and growth factors for effective regeneration of the osteochondral interface. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011. November;17(21-22):2845-55. Epub 2011 Aug 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith L, Xia Y, Galatz LM, Genin GM, Thomopoulos S. Tissue-engineering strategies for the tendon/ligament-to-bone insertion. Connect Tissue Res. 2012;53(2):95-105. Epub 2011 Dec 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Medtronic. INFUSE(R) bone graft. 2016. http://www.infusebonegraft.com. Accessed 2016 Mar 24.

- 14.Carragee EJ, Hurwitz EL, Weiner BK. A critical review of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 trials in spinal surgery: emerging safety concerns and lessons learned. Spine J. 2011. June;11(6):471-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weiss KR. “To B(MP-2) or not to B(MP-2)” or “much ado about nothing”: are orthobiologics in tumor surgery worth the risks? Clin Cancer Res. 2015. July 1;21(13):2889-91. Epub 2015 Jan 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skovrlj B, Koehler SM, Anderson PA, Qureshi SA, Hecht AC, Iatridis JC, Cho SK. Association between BMP-2 and carcinogenicity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2015. December;40(23):1862-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dohan Ehrenfest DM, Andia I, Zumstein MA, Zhang CQ, Pinto NR, Bielecki T. Classification of platelet concentrates (platelet-rich plasma-PRP, platelet-rich fibrin-PRF) for topical and infiltrative use in orthopedic and sports medicine: current consensus, clinical implications and perspectives. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2014. January;4(1):3-9. Epub 2014 May 8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheth U, Simunovic N, Klein G, Fu F, Einhorn TA, Schemitsch E, Ayeni OR, Bhandari M. Efficacy of autologous platelet-rich plasma use for orthopaedic indications: a meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012. February 15;94(4):298-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu CH, Chang YH, Lin SY, Li KC, Hu YC. Recent progresses in gene delivery-based bone tissue engineering. Biotechnol Adv. 2013. December;31(8):1695-706. Epub 2013 Aug 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evans CH, Ghivizzani SC, Robbins PD. Orthopedic gene therapy—lost in translation? J Cell Physiol. 2012. February;227(2):416-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kempen DH, Lu L, Heijink A, Hefferan TE, Creemers LB, Maran A, Yaszemski MJ, Dhert WJ. Effect of local sequential VEGF and BMP-2 delivery on ectopic and orthotopic bone regeneration. Biomaterials. 2009. May;30(14):2816-25. Epub 2009 Feb 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel ZS, Young S, Tabata Y, Jansen JA, Wong ME, Mikos AG. Dual delivery of an angiogenic and an osteogenic growth factor for bone regeneration in a critical size defect model. Bone. 2008. November;43(5):931-40. Epub 2008 Jul 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skobe M, Hawighorst T, Jackson DG, Prevo R, Janes L, Velasco P, Riccardi L, Alitalo K, Claffey K, Detmar M. Induction of tumor lymphangiogenesis by VEGF-C promotes breast cancer metastasis. Nat Med. 2001. February;7(2):192-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jain RK, Duda DG, Clark JW, Loeffler JS. Lessons from phase III clinical trials on anti-VEGF therapy for cancer. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2006. January;3(1):24-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shah SR, Werlang CA, Kasper FK, Mikos AG. Novel applications of statins for bone regeneration. Natl Sci Rev. 2015. March 1;2(1):85-99. Epub 2014 Aug 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bobyn JD, McKenzie K, Karabasz D, Krygier JJ, Tanzer M. Locally delivered bisphosphonate for enhancement of bone formation and implant fixation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009. November;91(Suppl 6):23-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laurencin CT, Ashe KM, Henry N, Kan HM, Lo KW. Delivery of small molecules for bone regenerative engineering: preclinical studies and potential clinical applications. Drug Discov Today. 2014. June;19(6):794-800. Epub 2014 Feb 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shah SR, Kasper FK, Mikos AG. Perspectives on the prevention and treatment of infection for orthopaedic tissue engineering applications. Chin Sci Bull. 2013;58(35):4342-8. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, Discher DE. Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell. 2006. August 25;126(4):677-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Banks JM, Mozdzen LC, Harley BA, Bailey RC. The combined effects of matrix stiffness and growth factor immobilization on the bioactivity and differentiation capabilities of adipose-derived stem cells. Biomaterials. 2014. October;35(32):8951-9. Epub 2014 Jul 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen MC, Sun YC, Chen YH. Electrically conductive nanofibers with highly oriented structures and their potential application in skeletal muscle tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2013. March;9(3):5562-72. Epub 2012 Oct 23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qazi TH, Mooney DJ, Pumberger M, Geissler S, Duda GN. Biomaterials based strategies for skeletal muscle tissue engineering: existing technologies and future trends. Biomaterials. 2015;53:502-21. Epub 2015 Mar 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ito H. Chemokines in mesenchymal stem cell therapy for bone repair: a novel concept of recruiting mesenchymal stem cells and the possible cell sources. Mod Rheumatol. 2011. April;21(2):113-21. Epub 2010 Sep 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siebers MC, ter Brugge PJ, Walboomers XF, Jansen JA. Integrins as linker proteins between osteoblasts and bone replacing materials. A critical review. Biomaterials. 2005. January;26(2):137-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, Slaper-Cortenbach I, Marini F, Krause D, Deans R, Keating A, Prockop Dj, Horwitz E. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8(4):315-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Al-Nbaheen M, Vishnubalaji R, Ali D, Bouslimi A, Al-Jassir F, Megges M, Prigione A, Adjaye J, Kassem M, Aldahmash A. Human stromal (mesenchymal) stem cells from bone marrow, adipose tissue and skin exhibit differences in molecular phenotype and differentiation potential. Stem Cell Rev. 2013. February;9(1):32-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Veronesi F, Maglio M, Tschon M, Aldini NN, Fini M. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells for cartilage tissue engineering: state-of-the-art in in vivo studies. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2014. July;102(7):2448-66. Epub 2013 Aug 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Coppi P, Bartsch G Jr, Siddiqui MM, Xu T, Santos CC, Perin L, Mostoslavsky G, Serre AC, Snyder EY, Yoo JJ, Furth ME, Soker S, Atala A. Isolation of amniotic stem cell lines with potential for therapy. Nat Biotechnol. 2007. January;25(1):100-6. Epub 2007 Jan 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nogami M, Tsuno H, Koike C, Okabe M, Yoshida T, Seki S, Matsui Y, Kimura T, Nikaido T. Isolation and characterization of human amniotic mesenchymal stem cells and their chondrogenic differentiation. Transplantation. 2012. June 27;93(12):1221-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Riekstina U, Muceniece R, Cakstina I, Muiznieks I, Ancans J. Characterization of human skin-derived mesenchymal stem cell proliferation rate in different growth conditions. Cytotechnology. 2008. November;58(3):153-62. Epub 2009 Feb 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ball MD, Bonzani IC, Bovis MJ, Williams A, Stevens MM. Human periosteum is a source of cells for orthopaedic tissue engineering: a pilot study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011. November;469(11):3085-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bieback K, Kern S, Klüter H, Eichler H. Critical parameters for the isolation of mesenchymal stem cells from umbilical cord blood. Stem Cells. 2004;22(4):625-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tan Q, Lui PP, Rui YF, Wong YM. Comparison of potentials of stem cells isolated from tendon and bone marrow for musculoskeletal tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012. April;18(7-8):840-51. Epub 2011 Dec 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wen Y, Jiang B, Cui J, Li G, Yu M, Wang F, Zhang G, Nan X, Yue W, Xu X, Pei X. Superior osteogenic capacity of different mesenchymal stem cells for bone tissue engineering. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2013. November;116(5):e324-32. Epub 2012 Jul 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Giuliani A, Manescu A, Langer M, Rustichelli F, Desiderio V, Paino F, De Rosa A, Laino L, d’Aquino R, Tirino V, Papaccio G. Three years after transplants in human mandibles, histological and in-line holotomography revealed that stem cells regenerated a compact rather than a spongy bone: biological and clinical implications. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2013. April;2(4):316-24. Epub 2013 Mar 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Caplan AI, Correa D. The MSC: an injury drugstore. Cell Stem Cell. 2011. July 8;9(1):11-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shi M, Liu ZW, Wang FS. Immunomodulatory properties and therapeutic application of mesenchymal stem cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2011. April;164(1):1-8. Epub 2011 Feb 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lalu MM, McIntyre L, Pugliese C, Fergusson D, Winston BW, Marshall JC, Granton J, Stewart DJ; Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. Safety of cell therapy with mesenchymal stromal cells (SafeCell): a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e47559 Epub 2012 Oct 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Si YL, Zhao YL, Hao HJ, Fu XB, Han WD. MSCs: Biological characteristics, clinical applications and their outstanding concerns. Ageing Res Rev. 2011. January;10(1):93-103. Epub 2010 Aug 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wakitani S, Okabe T, Horibe S, Mitsuoka T, Saito M, Koyama T, Nawata M, Tensho K, Kato H, Uematsu K, Kuroda R, Kurosaka M, Yoshiya S, Hattori K, Ohgushi H. Safety of autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell transplantation for cartilage repair in 41 patients with 45 joints followed for up to 11 years and 5 months. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2011. February;5(2):146-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Burkus JK, Heim SE, Gornet MF, Zdeblick TA. Is INFUSE bone graft superior to autograft bone? An integrated analysis of clinical trials using the LT-CAGE lumbar tapered fusion device. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2003. April;16(2):113-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hernigou P, Flouzat-Lachaniette CH, Delambre J, Poignard A, Allain J, Chevallier N, Rouard H. Osteonecrosis repair with bone marrow cell therapies: state of the clinical art. Bone. 2015. January;70:102-9. Epub 2014 Jul 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kuroda R, Matsumoto T, Niikura T, Kawakami Y, Fukui T, Lee SY, Mifune Y, Kawamata S, Fukushima M, Asahara T, Kawamoto A, Kurosaka M. Local transplantation of granulocyte colony stimulating factor-mobilized CD34+ cells for patients with femoral and tibial nonunion: pilot clinical trial. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2014. January;3(1):128-34. Epub 2013 Dec 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Calori GM, Colombo M, Mazza E, Ripamonti C, Mazzola S, Marelli N, Mineo GV. Monotherapy vs. polytherapy in the treatment of forearm non-unions and bone defects. Injury. 2013. January;44(Suppl 1):S63-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Desai P, Hasan SM, Zambrana L, Hegde V, Saleh A, Cohn MR, Lane JM. Bone mesenchymal stem cells with growth factors successfully treat nonunions and delayed unions. HSS J. 2015. July;11(2):104-11. Epub 2015 Mar 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hwang JH, Lee SH, Park HY, Kim MJ. Autologous bone marrow transplantation in osteonecrosis of the femoral head. J Tissue Sci Eng. 2011. February;2:103 Epub 2011 Feb 14. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aarvold A, Smith JO, Tayton ER, Jones AM, Dawson JI, Lanham S, Briscoe A, Dunlop DG, Oreffo RO. A tissue engineering strategy for the treatment of avascular necrosis of the femoral head. Surgeon. 2013. December;11(6):319-25. Epub 2013 Mar 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aoyama T, Goto K, Kakinoki R, Ikeguchi R, Ueda M, Kasai Y, Maekawa T, Tada H, Teramukai S, Nakamura T, Toguchida J. An exploratory clinical trial for idiopathic osteonecrosis of femoral head by cultured autologous multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells augmented with vascularized bone grafts. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2014. August;20(4):233-42. Epub 2014 Apr 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jo CH, Lee YG, Shin WH, Kim H, Chai JW, Jeong EC, Kim JE, Shim H, Shin JS, Shin IS, Ra JC, Oh S, Yoon KS. Intra-articular injection of mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a proof-of-concept clinical trial. Stem Cells. 2014. May;32(5):1254-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ha CW, Cho JJ, Elmallah RK, Cherian JJ, Kim TW, Lee MC, Mont MA. A multicenter, single-blind, Phase IIa clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a cell-mediated gene therapy in degenerative knee arthritis patients. Hum Gene Ther Clin Dev. 2015. June;26(2):125-30. Epub 2015 Apr 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Delcogliano M, de Caro F, Scaravella E, Ziveri G, De Biase CF, Marotta D, Marenghi P, Delcogliano A. Use of innovative biomimetic scaffold in the treatment for large osteochondral lesions of the knee. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014. June;22(6):1260-9. Epub 2013 Oct 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kon E, Delcogliano M, Filardo G, Busacca M, Di Martino A, Marcacci M. Novel nano-composite multilayered biomaterial for osteochondral regeneration: a pilot clinical trial. Am J Sports Med. 2011. June;39(6):1180-90. Epub 2011 Feb 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kon E, Filardo G, Di Martino A, Busacca M, Moio A, Perdisa F, Marcacci M. Clinical results and MRI evolution of a nano-composite multilayered biomaterial for osteochondral regeneration at 5 years. Am J Sports Med. 2014. January;42(1):158-65. Epub 2013 Oct 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Panteli M, Pountos I, Jones E, Giannoudis PV. Biological and molecular profile of fracture non-union tissue: current insights. J Cell Mol Med. 2015. April;19(4):685-713. Epub 2015 Mar 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mont MA, Cherian JJ, Sierra RJ, Jones LC, Lieberman JR. Nontraumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head: where do we stand today? A ten-year update. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015. October 7;97(19):1604-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nicolini AP, Carvalho RT, Dragone B, Lenza M, Cohen M, Ferretti M. Updates in biological therapies for knee injuries: full thickness cartilage defect. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2014. September;7(3):256-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Homma Y, Zimmermann G, Hernigou P. Cellular therapies for the treatment of non-union: the past, present and future. Injury. 2013. January;44(Suppl 1):S46-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Megas P. Classification of non-union. Injury. 2005. November;36(Suppl 4):S30-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hwang do W, Jang SJ, Kim YH, Kim HJ, Shim IK, Jeong JM, Chung JK, Lee MC, Lee SJ, Kim SU, Kim S, Lee DS. Real-time in vivo monitoring of viable stem cells implanted on biocompatible scaffolds. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008. October;35(10):1887-98. Epub 2008 Apr 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wood JJ, Malek MA, Frassica FJ, Polder JA, Mohan AK, Bloom ET, Braun MM, Coté TR. Autologous cultured chondrocytes: adverse events reported to the United States Food and Drug Administration. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006. March;88(3):503-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Adachi N, Ochi M, Deie M, Nakamae A, Kamei G, Uchio Y, Iwasa J. Implantation of tissue-engineered cartilage-like tissue for the treatment for full-thickness cartilage defects of the knee. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014. June;22(6):1241-8. Epub 2013 May 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Di Bella C, Fosang A, Donati DM, Wallace GG, Choong PF. 3D Bioprinting of cartilage for orthopedic surgeons: reading between the lines. Front Surg. 2015;2:39 Epub 2015 Aug 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kang HW, Lee SJ, Ko IK, Kengla C, Yoo JJ, Atala A. A 3D bioprinting system to produce human-scale tissue constructs with structural integrity. Nat Biotechnol. 2016. March;34(3):312-9. Epub 2016 Feb 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shah SR, Tatara AM, D'Souza RN, Mikos AG, Kasper FK. Evolving strategies for preventing biofilm on implantable materials. Mater Today. 2013;16:177-82. [Google Scholar]