Abstract

Roughly one-third of individuals living with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are coinfected with the hepatitis C virus (HCV) due to shared routes of transmission. HIV accelerates the progression of HCV disease; thus, coinfected individuals are at high priority for HCV treatment. Several new HCV therapies, called direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs), are available that achieve cure rates of >90% in many patient populations including individuals with HIV. The primary consideration in treating HCV in HIV-infected persons is the potential for drug interactions. We describe the clinical pharmacology and drug interaction potential of the DAAs, review the interaction data with DAAs and antiretroviral agents, and identify the knowledge gaps in the pharmacologic aspects of treating HCV in individuals with HIV coinfection. This review will focus on DAAs that have received regulatory approval in the United States and Europe and agents in late stages of clinical development.

Keywords: hepatitis C virus, human immunodeficiency virus, coinfection, drug interactions, direct-acting antivirals

Roughly one-third of individuals living with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are coinfected with the hepatitis C virus (HCV) due to shared routes of transmission [1, 2]. HIV accelerates the progression of HCV disease. Individuals with HIV coinfection have higher HCV RNA, a more rapid progression of fibrosis, and an increased frequency of liver decompensation and death [3–6]. Due to the increased risks associated with HIV coinfection, treatment guidelines consider this patient population a “high priority” for HCV treatment [7, 8].

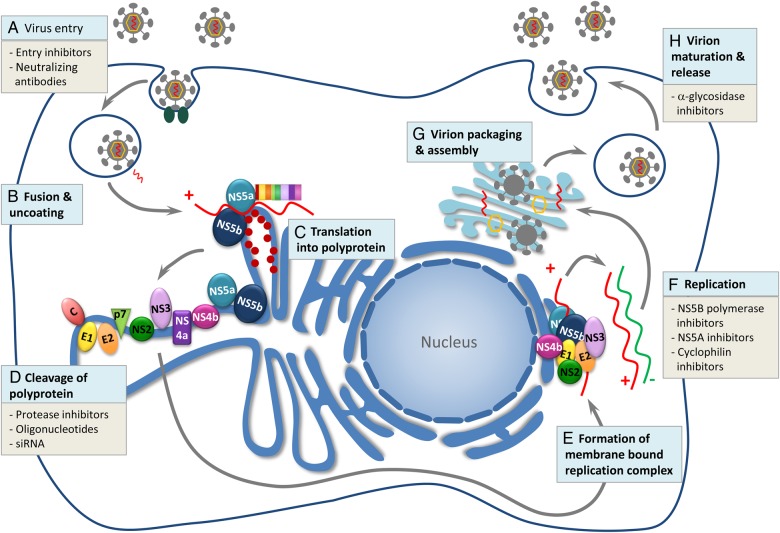

There have been significant advances in the treatment of HCV in recent years. Pegylated interferon alfa (PEG) and ribavirin (RBV) were the standard of care for this disease for decades, but several agents that directly target specific steps in the HCV lifecycle (Figure 1) have recently received regulatory approval [9]. The approved direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) inhibit 3 specific steps in the HCV lifecycle including the NS3/4A protease enzyme, NS5A protein, and the NS5B polymerase. Inhibition of the NS3 protease prevents the cleavage of the replication complex responsible for formation of viral RNA. The NS5B enzyme is essential for HCV replication as it catalyzes the synthesis of the complementary minus-strand RNA and subsequent genomic plus-strand RNA. There are 2 types of NS5B RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitors: nucleotide and nonnucleoside inhibitors. The nucleotide inhibitors are active site inhibitors, whereas the nonnucleoside inhibitors are allosteric inhibitors. Another target, NS5A, encodes a protein that appears to be essential to the replication machinery of HCV and critical in the assembly of new infectious viral particles. However, the specific functions of this protein have not been established.

Figure 1.

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) life cycle. Reprinted with permission from [9]. A, The virus gains entry by receptor-mediated endocytosis. B, Fusion and uncoating occur and the HCV genomic RNA is released from the nucleocapsid into the cytoplasm. C, Translation into a single large polyprotein occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum. D, This polyprotein is then cleaved by viral and host proteases into 10 mature HCV proteins, including structural proteins (HCV core protein and envelope proteins E1 and E2) and nonstructural proteins (P7, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A, and NS5B). E, These viral and host proteins form a membrane-bound replication complex. F, Transcription takes place, dependent upon the RNA helicase (RNA-dependent RNA polymerase or NS5B polymerase) where the positive-strand RNA serves as a template for transcription. G, Virion assembly occurs in the Golgi apparatus when viral glycoproteins combine with newly produced RNA. H, Virion maturation, budding, and release from the hepatocyte occurs. The site of action of current direct-acting antiviral agents are listed at each step in the HCV life cycle. Abbreviation: siRNA, small interfering RNA.

Relative to PEG plus RBV, DAAs are well tolerated, administered for shorter treatment durations (eg, 8–24 weeks), and ultimately achieve high rates of cure (>90%), otherwise known as a sustained virologic response (SVR), in many patient populations. While RBV is still used in combination with DAAs in certain clinical scenarios, PEG is seldom used.

HIV-coinfected individuals were less likely to achieve SVR with PEG plus RBV compared with HCV-monoinfected individuals [10]; however, this is not the case with newer DAAs. Multiple studies indicate similar SVR rates in trials of HIV-coinfected individuals to those observed in trials of HCV-monoinfected individuals [11]. Thus, the primary consideration in treating HCV in individuals with HIV coinfection is the potential for drug interactions between DAAs and antiretroviral (ARV) agents.

The purpose of this manuscript is to describe the clinical pharmacology and drug interaction potential of the DAAs, review the interaction data with DAAs and ARV agents, and to identify the knowledge gaps in the pharmacologic aspects of treating HCV in individuals with HIV coinfection. This review will focus on DAAs that have received regulatory approval in the United States and Europe and those in late stages of clinical development. The epidemiology of HCV infection and reinfection, disease progression, and the efficacy of emerging HCV treatment strategies in persons coinfected with HIV/HCV are reviewed in a companion article in this issue [12].

SOFOSBUVIR

Sofosbuvir (SOF) is an NS5B polymerase inhibitor. SOF is used in combination with RBV and/or with other DAAs for the treatment of HCV. SOF is administered as a phosphoramidate prodrug of the uridine nucleotide analogue GS-331007 monophosphate [13]. Once inside cells, SOF is hydrolyzed by cathepsin A and/or carboxyesterase 1 to GS-331007 monophosphate [13, 14]. GS-331007 monophosphate is then phosphorylated by uridine monophosphate-cytidine monophosphate kinase to the GS-331007 diphosphate form, which is then phosphorylated by nucleotide diphosphate kinase to the triphosphate moiety (GS-461203) [13, 14]. GS-461203 is the active form of SOF. When GS-461203 is incorporated into HCV RNA by the NS5B polymerase rather than the endogenous base, HCV replication is halted. The primary drug-related material circulating in plasma is GS-331007. GS-331007 has no antiviral activity.

The absolute bioavailability of SOF has not been determined, but is estimated to be at least 80% based on recovery of SOF and its primary metabolite, GS-331007, following administration of a radiolabeled dose [14]. A high-fat meal increases SOF area under the concentration time curve (AUC) by 67%–91%, but the increase is not thought to increase the likelihood of toxicities based on the wide therapeutic index of the drug [14]. SOF is 61%–65% protein bound, and is primarily renally excreted [15]. For the pharmacokinetic properties of SOF, refer to Table 1. SOF is not a substrate, nor does it inhibit or induce any cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes, and therefore it has a low potential for drug interactions. However, SOF is a substrate for the efflux transporters P-glycoprotein (P-gp) and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) [16]. The SOF AUC is increased 2.3-fold and 2.5-fold in patients with moderate and severe hepatic impairment (ie, Child-Pugh class B and C), respectively, but GS-331007 AUC is unchanged, and no dose adjustment is needed for this population. In fact, SOF, in combination with other agents such as RBV and the NS5A inhibitors ledipasvir (LDV) or daclatasvir (DCV), is the preferred treatment for individuals with decompensated cirrhosis. In contrast, SOF and GS-331007 pharmacokinetics are affected by renal impairment, and use of this drug is limited in this population. SOF AUC is 61%, 107%, and 171% higher in mild (glomerular filtration rate [GFR] ≥ 50/minute/1.73 m2 and <80 mL/minute/1.73 m2), moderate (GFR ≥ 30/minute/1.73 m2 and <50 mL/minute/1.73 m2), and severe (GFR < 30 mL/minute/1.73 m2) renal impairment, respectively, whereas GS-331007 AUC is increased 55%, 88% and 451% in mild, moderate, and severe renal impairment, respectively [14, 16]. Studies are ongoing to evaluate the safety and appropriate dosing of SOF in individuals with renal impairment.

Table 1.

Pharmacokinetic Properties of Direct-Acting Antiviral Agents

| Property | Sofosbuvir | Ledipasvir | Daclatasvir | Simeprevir | Velpatasvir | Paritaprevir | Ombitasvir | Dasabuvir | Grazoprevir | Elbasvir |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral bioavailability | Not established | Not established | 67% | Not established | No data | Not established | Not established | 70% | 10%–40% | 30% |

| Plasma T1/2 | Parent compound: 0.4 h GS-331007: 27 h | 47 h | 12–15 h | 10–13 h | ∼15 h | 5.5 h | 21–25 h | 5.5–6 h | 30 h | 23 h |

| Plasma protein binding | 61%–65% | >99.8% | 99% | 99.9% | No data | 97%–98.6% | 99.9% | >99.5% | 98% | >99% |

| Hepatically metabolized | 14% | 86% | 88% | 91% | No data | 88% | 90.2% | 94.4% | >90% | >90% |

| Renal excretion | 80% | 1% | 7% | <1% | <1% | 8.8% | 1.91% | 2% | <1% | <1% |

| Route of metabolism | Phosphorylated by host enzymes, eliminated renally | Slow oxidative metabolism via an unknown mechanism | Primarily hepatic via CYP3A | Hepatic via CYP3A | Hepatic via CYP3A4, 2C8, and 2B6 | Hepatic via CYP3A4 and to a lesser extent by CYP3A5 | Amide hydrolysis followed by oxidative metabolism | Hepatic via CYP2C8, and to a lesser extent by CYP3A | Hepatic via CYP3A4 | Hepatic via CYP3A4 |

| Transporter substrate | P-gp and BCRP | P-gp | P-gp | P-gp | P-gp | P-gp, OATP1B1, BCRP | P-gp | P-gp | P-gp and OATP1B1 | P-gp |

| Enzyme inhibition | None | None | CYP3A4 | Inhibits intestinal CYP3A | None | CYP2C8, UGT1A1 (ritonavir inhibits CYP3A) | CYP2C8, UGT1A1 | UGT1A1 | CYP3A4 | None |

| Enzyme induction | None | None | None | None | None | None | None | None | None | None |

| Transporter inhibition | None | P-gp, BCRP | P-gp, BCRP, OATP1B1/3 | P-gp and OATP1B1 | P-gp, BCRP, OATP1B1/1B3 | P-gp, OATP1B1/3, BCRP | BCRP | UGT1A1 and BCRP | BCRP and P-gp |

Abbreviations: BCRP, breast cancer resistance protein; CYP, cytochrome P450; P-gp, P-glycoprotein; T1/2, half-life.

Given that SOF is not a substrate, inhibitor, or inducer of CYP enzymes, it has a low potential for drug interactions. However, potent inducers of P-gp or BCRP (eg, carbamazepine, rifampin, or St John's wort) should not be used with SOF. When combined with amiodarone, patients receiving SOF with other various DAAs have had serious symptomatic bradycardia. Whether this represents an unexpected drug interaction is unclear [17], but the combination should be avoided if possible.

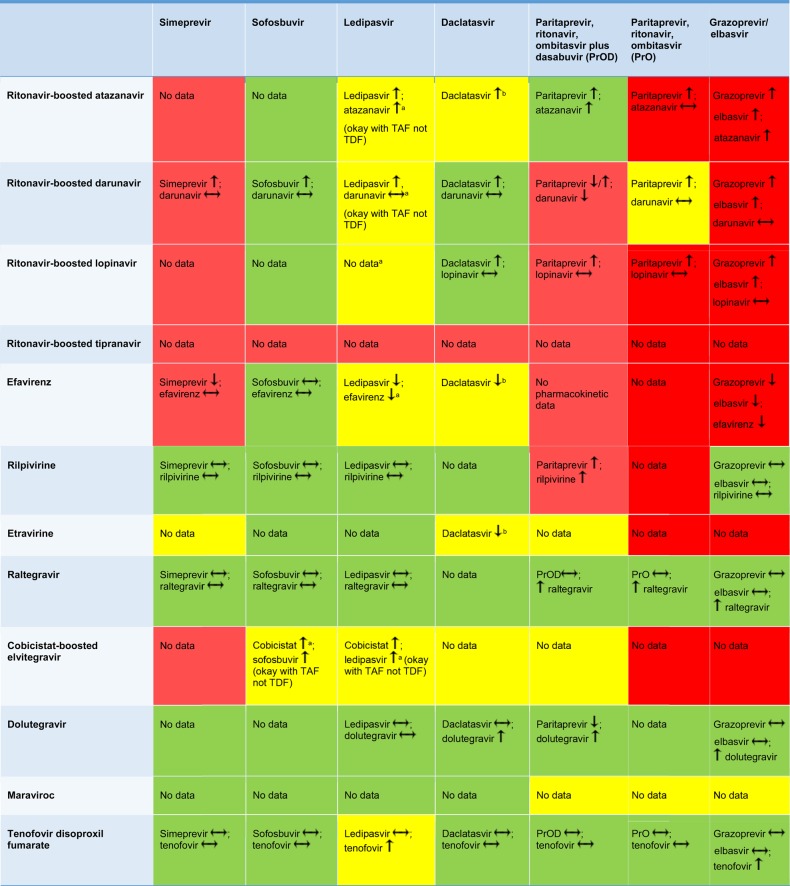

SOF has been studied with several ARV agents (the fixed-dose combination of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate [TDF]/emtricitabine/efavirenz, ritonavir-boosted darunavir, raltegravir, and rilpivirine) in healthy volunteers [18]. There were minimal changes in the pharmacokinetics of the ARVs, SOF, and GS-331007. Raltegravir AUC was reduced by 17% and tenofovir maximum serum concentration (Cmax) was increased by 25% with no change in the tenofovir AUC. SOF and GS-331007 AUC were increased 37% and 19%, respectively, with ritonavir-boosted darunavir, while GS-331007 AUC and Cmax were reduced 17%–23% with the fixed-dose combination of TDF/emtricitabine/efavirenz. These changes are unlikely to have clinical relevance, but interactions must be considered with the DAAs given with SOF. Of note, ritonavir-boosted tipranavir has not been studied with SOF, but because this protease inhibitor is a potent P-gp inducer, it is likely to reduce SOF exposures and is thus not recommended [18]. Figure 2 provides a summary of drug interactions with SOF and ARVs. This table is updated regularly and is available through the “Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C” guidance at www.hcvguidelines.org [7].

Figure 2.

Drug interactions between direct-acting antivirals and antiretroviral drugs. Red, combination should not be used; yellow, use with caution or increased monitoring; and green, suitable for coadministration [7]. aWatch renal function, tenofovir levels increased; bDecrease daclatasvir (DCV) dose to 30 mg QD, increase DCV dose to 90 mg QD. Up arrow is an increase in the concentration, down arrow is a decrease in the concentration, and a horizontal arrow means no change in the concentration. Abbreviations: TAF, tenofovir alafenamide; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate.

A summary of the efficacy and safety of SOF, in combination with RBV, in HIV-coinfected individuals follows. The efficacy and safety of SOF when combined with DAAs is reviewed in subsequent sections. The PHOTON-1 study evaluated the use of SOF and weight-based RBV (1000 mg or 1200 mg in divided doses) in treatment-naive genotype 1, 2, and 3 patients as well as treatment-experienced genotype 2 and 3 patients with HIV coinfection. This study enrolled 223 patients into 3 treatment arms: 114 treatment-naive patients with genotype 1 treated for 24 weeks, 68 treatment-naive patients with genotypes 2 and 3 treated for 12 weeks, and 41 treatment-experienced patients with genotypes 2 and 3 treated for 24 weeks. Of the 223 patients, 212 (95%) were receiving ARV with TDF/emtricitabine plus one of the following: efavirenz, ritonavir-boosted atazanavir, ritonavir-boosted darunavir, raltegravir, or rilpivirine. Roughly 10% of patients had cirrhosis. In the treatment-naive participants, the SVR rates were 76%, 88%, and 67% for genotypes 1, 2 and 3, respectively. Among treatment-experienced participants who were treated for 24 weeks, 92% and 94% of individuals with genotypes 2 and 3, respectively, achieved SVR. Overall this regimen was well tolerated, with the most common adverse events being fatigue (37%), insomnia (17%), headache (13%), and nausea (16%). The most common abnormal laboratory values were declines in hemoglobin and elevations in direct bilirubin. Thirty-four patients (15%) had decreases in hemoglobin <10 mg/dL, with 3 patients experiencing decreases in hemoglobin to <8.5 mg/dL. Forty-three patients (19%) required dose reduction of RBV [19]. The PHOTON-2 study also evaluated SOF and RBV in HIV-coinfected treatment-naive patients with genotypes 1–4 and treatment-experienced patients with genotypes 2 and 3. Of the 275 patients enrolled, 265 (96%) were receiving ARV with the same ARVs as in PHOTON-1. In this study, 19.6% had cirrhosis. In treatment-naive patients, SVR rates were 85%, 89%, 91%, and 84% for genotypes 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively; in treatment-experienced genotype 2 and 3 patients, SVR rates were 83% and 86%, respectively. Similar to PHOTON-1, the participants in PHOTON-2 experienced fatigue, insomnia, asthenia, headache, anemia, and increase in bilirubin. Twenty-six patients (9%) experienced a hemoglobin level <10 mg/dL, and 1 patient (<1%) had a hemoglobin level <8.5 mg/dL. Among patients who completed treatment, 30 (11%) required reductions in RBV dose [20].

DACLATASVIR

DCV is an HCV NS5A replication complex inhibitor that binds to the N-terminus of NS5A. DCV has been studied in combination with the HCV protease inhibitor asunaprevir and a nonnucleoside NS5B inhibitor, beclabuvir, but these drugs are not available in the United States. DCV has also been studied with the HCV protease inhibitor simeprevir (SIM) [21]. However, the primary use of DCV in the United States is in combination with SOF. DCV/SOF has regulatory approval for genotype 3 disease, in individuals with genotype 1 or 3 who are coinfected with HIV, and with or without RBV in individuals with genotype 1 or 3 infection with advanced liver disease.

The absolute bioavailability of DCV is 67%. A high-fat, high-calorie meal reduces DCV exposures by 23%, but a low-fat meal has no effect. DCV is 99% protein bound and has minimal renal excretion [22]. For the pharmacokinetic properties of DCV, refer to Table 1. DCV is metabolized by CYP3A. However, DCV does not appear to inhibit or induce any CYP enzymes. DCV is a substrate for P-gp and DCV inhibits P-gp, BCRP, and OATP1B1/3 [22]. Total exposures of DCV are 38% and 36% lower in patients with Child-Pugh class B and C decompensated cirrhosis, respectively, but unbound concentrations are unchanged. Thus, no dose adjustment is needed in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. The DCV AUC in patients with end-stage renal disease (estimated GFR [eGFR] <15 mL/minute/1.73 m2 receiving hemodialysis), eGFR 30–59 mL/minute/1.73 m2, and eGFR 15–29 mL/minute/1.73 m2 were 1.27, 2.10, and 1.94-fold higher, respectively, than those with normal renal function, which is more than expected as only 7% of the drug is renally eliminated [22]. The increase is hypothesized to relate to impaired hepatic metabolism as a consequence of uremic toxins or increases in parathyroid hormone, and/or cytokines in those with renal impairment, but given the wide therapeutic index of DCV, this change is unlikely to have clinical relevance.

DCV is primarily a victim of drug interactions rather than a perpetrator, although it does increase digoxin (a P-gp substrate) by 27%, and rosuvastatin (OAT1B1 and BCRP substrate) by 58%. Due to DCV being highly reliant on CYP3A for its metabolism, dose adjustments of DCV are necessary in the presence of strong or moderate CYP3A inhibitors and moderate inducers. Ketoconazole (a potent CYP3A4 inhibitor) increases the AUC of DCV by 200%, and multidose rifampin (a potent CYP3A4 inducer) decreases the AUC of DCV by 79% [22]. Strong inducers are contraindicated with DCV.

In terms of ARVs, DCV was studied with ritonavir-boosted atazanavir, efavirenz, and TDF in healthy volunteers. Ritonavir-boosted atazanavir increased DCV AUC by 2.1-fold, whereas efavirenz reduced DCV AUC by 32%. DCV dose modification from 60 mg to 30 mg with ritonavir-boosted atazanavir and 90 mg with efavirenz were predicted to normalize AUC relative to the target exposure [23, 24]. No interaction was observed with TDF [24]. A DCV dose reduction to 30 mg was assumed to be appropriate for other ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitors given the interaction observed with ritonavir-boosted atazanavir. However, the DCV AUC and Cmax with a 30 mg dose were 33% and 23% lower with ritonavir-boosted lopinavir and darunavir, respectively, vs 60 mg of DCV [25]. Thus, no dose adjustment of DCV is necessary with ritonavir-boosted lopinavir or darunavir. DCV increases dolutegravir AUC and Cmax by approximately 33% and 29%, respectively, but this increase is unlikely to have clinical implications [26]. Figure 2 provides a summary of drug interactions with DCV and ARVs. This table is updated regularly and is available through the “Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C” guidance at www.hcvguidelines.org [7].

The combination of SOF and DCV, administered for 12 weeks, was evaluated in 151 HIV/HCV-coinfected individuals in the ALLY-2 trial [11]. This study included treatment-naive and treatment-experienced patients with genotypes 1–4. Treatment-naive patients received either 8 or 12 weeks of treatment, and the experienced patients received 12 weeks. Patients taking ritonavir-boosted atazanavir, lopinavir, or darunavir received 30 mg once daily of DCV and those taking either efavirenz or nevirapine received 90 mg DCV daily. All others received the standard 60-mg dose of DCV. Approximately 14% of patients in this trial had cirrhosis. The SVR rate for all genotypes was 97% following 12 weeks of treatment and 76% with 8 weeks of treatment. Fifty-one subjects (25% of the study population) were taking ritonavir-boosted darunavir, and slightly lower SVR rates were observed in these patients (93.3% when treated for 12 weeks and 66.4% when treated for 8 weeks). Nine of the 12 patients who experienced viral relapse in this study were receiving ritonavir-boosted darunavir. Patients received the reduced (30 mg) DCV dose prior to the availability of pharmacokinetic data demonstrating the dose was suboptimal with ritonavir-boosted lopinavir and darunavir. Thus, low DCV exposures in those on ritonavir-boosted darunavir may have contributed to viral failure in this study. A higher proportion of patients on ritonavir-boosted darunavir received the 8-week treatment duration, and this group had high baseline HCV RNA values, which also contributed to virologic failure [11, 27]. The most common treatment-related adverse events in this study were fatigue (17%), nausea (13%), and headache (11%).

LEDIPSAVIR

LDV is an inhibitor of NS5A and is only available coformulated with SOF. SOF/LDV is approved for genotypes 1, 4, 5, and 6. SOF/LDV is also approved for genotype 1 and 4 liver transplant recipients as well as genotype 1 infection with decompensated cirrhosis [16].

The bioavailability of LDV in humans is unknown, but ranges from 30% to 50% in rats, monkeys, and dogs. LDV concentrations are similar when given fasted vs with a moderate-fat (600 kcal) or high-fat (1000 kcal) meal. LDV is >99.8% bound to human plasma proteins and is primarily eliminated unchanged in the feces. For the pharmacokinetic properties of LDV, refer to Table 1. Approximately 30% is metabolized, though the precise enzymes involved are uncertain. LDV is a substrate for and also inhibits P-gp and BCRP. LDV pharmacokinetics are not significantly altered by hepatic or renal impairment, but because the drug is coformulated with SOF, the same limitations on use in those with renal impairment apply [16].

LDV relies on an acidic environment for optimal absorption, so gastric acid modifiers should be used with caution. In one large cohort, use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) was found to be an independent predictor of relapse to LDV/SOF treatment [28]. If gastric acid modifiers must be used, temporal separation is necessary with antacids (by 4 hours), and histamine-2 receptor antagonists (eg, famotidine, ranitidine) and PPI (eg, omeprazole, lansoprazole) doses should not exceed the equivalent of 40 mg famotidine twice daily and 20 mg omeprazole once daily, respectively. The PPI must be administered simultaneously with LDV/SOF in the fasted state [29]. Given that LDV inhibits P-gp and BCRP, LDV may increase the concentrations of rosuvastatin (an OATP1B1 and BCRP substrate), so this combination is not recommended. Rosuvastatin AUC was increased by 699% with LDV, GS-9451 (an investigational protease inhibitor), and tegobuvir (an investigational nonnucleoside NS5B inhibitor) [30]. It is unknown whether LDV would cause this effect on rosuvastatin (or an increase of this same magnitude) in the absence of these other DAAs [31].

LDV has been studied with several ARV agents. The CYP3A inducer efavirenz reduces LDV concentrations by 30% and the pharmacokinetic enhancer cobicistat increases LDV concentrations by 2-fold, but given the rather wide therapeutic index of LDV, these changes are not expected to have clinical relevance [32]. LDV increases tenofovir exposures, which may increase the risk of renal toxicity in HIV-infected individuals taking TDF with a ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitor or cobicistat [33]. A new formulation of tenofovir, tenofovir alafenamide (TAF), may be used in place of TDF as the tenofovir concentrations are 5-fold lower than with TDF [34]. Figure 2 provides a summary of drug interactions with LDV and ARVs. This table is updated regularly and is available through the “Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C” guidance at www.hcvguidelines.org [7].

SOF/LDV has been studied in 2 separate trials of HIV/HCV-coinfected individuals. The ERADICATE trial evaluated 50 noncirrhotic HIV/HCV-coinfected individuals with HCV genotype 1. In this study, 49 subjects (98%) achieved SVR12 and 1 patient relapsed 4 weeks after completing treatment [35]. The ION-4 trial evaluated SOF/LDV for 12 weeks in 335 patients with HIV coinfection. Participants were primarily (97.6%) genotype 1 infected. Eight patients had HCV genotype 4. Fifty-five percent of patients were treatment experienced, 34% were black, and 20% had cirrhosis; all patients were receiving ARV comprised of TDF/emtricitabine plus efavirenz, raltegravir, or rilpivirine. Ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitors were excluded. SVR rates were 96% for genotype 1 and 100% for genotype 4. Among the patients who did not achieve SVR, 1 patient died after 4 weeks of treatment, 2 had HCV breakthrough during treatment that was associated with suspected poor adherence, and 10 had an HCV relapse. Of the 10 patients with a virologic relapse, all were black, 6 were treatment experienced, 3 had cirrhosis, 1 was treatment experienced and cirrhotic, 7 had the unfavorable IL28B TT allele, and 8 received efavirenz [36]. LDV exposures (determined through population pharmacokinetic modeling) were similar, however, in the individuals on efavirenz compared with individuals on other ARVs.

SIMEPREVIR

SIM is an inhibitor of the HCV NS3 protease. SIM is indicated in combination with SOF for the treatment of HCV-infected individuals with genotype 1 or 4 infection. This combination represented the first interferon-free treatment with DAAs for individuals with genotype 1 disease, but its use has been largely replaced by less expensive combinations of DAAs.

The mean absolute bioavailability of SIM is 62%. A 533-kcal meal and 928-kcal meal increase SIM AUC by 69% and 61%, respectively. Thus, it is recommended to take with food. SIM is 99.9% protein bound, primarily to albumin, and <1% of SIM is renally cleared [37]. For the pharmacokinetic properties of SIM, refer to Table 1. SIM is metabolized by CYP3A and is a substrate for P-gp, MRP2, BCRP, OATP1B1/3, and OATP2B1. SIM is also a mild inhibitor of CYP1A2 and intestinal CYP3A, OATP1B1, NTCP, P-gp, MRP2, and BSEP. SIM exposures are increased 2.4-fold and 5.2-fold in patients with Child-Pugh class B and C hepatic impairment, respectively. There have been reports of hepatic decompensation, hepatic failure, and death in patients with advanced liver disease receiving SIM; consequently, it should be avoided in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. There is an 82% increase in exposure of SIM in those with eGFR < 30 mL/minute/1.73 m2, presumably due to the same mechanism(s) previously described for DCV [37]. Because SIM is used with SOF, the same limitations on use in those with eGFR <30 mL/minute/1.73 m2 apply.

In terms of SIM's ability to act as a perpetrator in drug interactions, SIM increases the AUC of oral midazolam (a CYP3A substrate) by 45%, digoxin (a P-gp substrate) by 39%, and rosuvastatin (an OATP1B1 and BCRP substrate) by 2.8-fold in healthy volunteers [38]. While these are significant changes in the AUC, coadministration is still appropriate with close monitoring for adverse effects. The rosuvastatin dose should not exceed 5 mg with initiation of SIM. As a victim, SIM is altered by moderate or strong inducers and inhibitors of CYP3A. Multidose rifampin, a potent CYP3A inducer, reduces SIM AUC by 48% and thus coadministration is not recommended. Although no effect of cyclosporine on SIM exposures was apparent in a drug interaction study in healthy volunteers, SIM exposures were 6-fold higher in those on cyclosporine vs historical values in individuals receiving SIM, DCV, and RBV treatment after liver transplant. Given this increase in SIM exposures, coadministration with cyclosporine is not recommended [37]. Cyclosporine inhibits OATP1B1, P-gp, and CYP3A, so any or all of these mechanisms may have contributed to the interaction observed.

Due to the effects of potent CYP3A inhibitors and inducers, ARV options are more limited with SIM. Efavirenz reduces SIM AUC by 71% [38]. SIM exposures are increased 2.6-fold by ritonavir-boosted darunavir, even after an empiric dose reduction of SIM from 150 mg to 50 mg. Thus, ritonavir- or cobicistat-boosted ARVs and efavirenz are not recommended with SIM. Rilpivirine, raltegravir, and TDF can be safely used with SIM. Figure 2 provides a summary of drug interactions with SIM and ARVs. This table is updated regularly and is available through the “Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C” guidance at www.hcvguidelines.org [7].

To date there are no formal studies of SIM/SOF in HIV-coinfected individuals. In 310 noncirrhotic HCV-monoinfected individuals receiving 12 weeks of SIM/SOF, SVR was achieved in 97% of treatment-naive and -experienced patients [39]. The SVR rate was 83% for 103 cirrhotic HCV-monoinfected individuals receiving 12 weeks of SIM/SOF; thus, extending treatment duration to 24 weeks is necessary for patients with cirrhosis [40].

VELPATASVIR

Velpatasvir (VEL) is an investigational NS5A inhibitor [41]. This drug is being developed as a fixed-dose combination tablet with SOF. It is expected to receive regulatory approval in June 2016.

VEL absorption is pH dependent, and gastric acid modifiers are problematic with this agent. If a PPI is required with VEL, it is recommended to take these agents 4 hours before with food and not to exceed a 20 mg equivalent of omeprazole [42]. There does not appear to be an appreciable food effect with VEL [43]. VEL is predominantly excreted in feces as parent and metabolite and <1% of the dose is excreted in urine. For the pharmacokinetic properties of VEL, refer to Table 1. VEL is metabolized by CYP3A4, CYP2C8, and CYP2B6, but has not been shown to inhibit any CYP enzymes. VEL is a substrate for P-gp, a weak inhibitor of P-gp, BCRP, and OATP1B1/1B3 but does not induce any transporters [44]. VEL AUC is 17% lower in patients with moderate hepatic impairment, but this is likely a protein-binding affect and unbound levels are unchanged. VEL AUC is increased 14% in those with severe hepatic impairment [45]. In patients with severe renal impairment (eGFR <30 mL/minute/1.73 m2), the AUC of VEL was increased by 50% [46]. Because VEL is used with SOF, the same limitations on use in those with eGFR <30 mL/minute/1.73 m2 apply.

In terms of VEL's ability to act as a perpetrator in interactions, pravastatin (an OATP1B1 substrate) AUC increased 35% and rosuvastatin (an OATP1B1 and BCRP substrate) AUC increased approximately 170% when coadministered with VEL in healthy volunteers. While no pravastatin dose adjustment is needed, the rosuvastatin dose should not exceed 10 mg with VEL. Digoxin (a P-gp substrate) AUC is increased 34%. Digoxin concentrations should be monitored during VEL treatment and doses adjusted as needed. In terms of its ability to act a victim in interactions, single-dose rifampin (an OATP1B1 inhibitor) increased VEL AUC by 47%. VEL AUC increased 103% with a single dose of cyclosporine (a mixed OATP/P-gp/MRP2 inhibitor). Ketoconazole (CYP3A inhibitor) increased VEL AUC by 70%. When coadministered with multiple doses of rifampin (a potent CYP3A inducer), VEL AUC was reduced by approximately 82% [44]. Rifampin, cyclosporine, and ketoconazole should be avoided with VEL.

Drug interaction studies with SOF/VEL and the following ARV regimens have been performed in healthy volunteers: TDF/emtricitabine/efavirenz; TDF/emtricitabine/rilpivirine; dolutegravir; raltegravir; elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/TAF; TDF/emtricitabine/ritonavir boosted atazanavir; TDF/emtricitabine/ritonavir boosted darunavir; and emtricitabine/TDF/ritonavir boosted lopinavir. VEL AUC was reduced 50% with TDF/emtricitabine/efavirenz. SOF/VEL increased tenofovir exposures by 40%–81% [47]. VEL AUC was increased by 2.4 fold with ritonavir-boosted atazanavir, and was also increased 20%–30% in the presence of cobicistat-containing regimens. When TDF was administered with SOF/VEL, there was a 20%–40% increase in tenofovir AUC [47]. As with LDV, this could be problematic in individuals receiving TDF with other agents that raise tenofovir exposures, but TAF is an alternative to TDF in this scenario.

A study of SOF/VEL in HCV/HIV-coinfected patients is currently under way (NCT02480712). SOF/VEL for 12 weeks was studied in 740 HCV-monoinfected individuals with genotypes 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6. Nineteen percent of the study participants had cirrhosis and 32% had failed prior HCV treatment. The overall SVR rate was 99%, with rates of 98%, 100%, 100%, 97%, and 100% for genotypes 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6, respectively [48]. The ASTRAL-2 study compared SOF/VEL for 12 weeks with SOF/RBV (the current standard of care for genotype 2) for 12 weeks in 266 HCV-monoinfected individuals with genotype 2. SVR was significantly higher (P = .018) with SOF/VEL relative to SOF/RBV [49]. ASTRAL-3 compared 12 weeks of SOF/VEL to 24 weeks of SOF plus RBV in 552 HCV-monoinfected individuals with HCV genotype 3. Approximately 30% of participants had cirrhosis and 26% were treatment experienced in each arm. SVR in the SOF/VEL group was 95% vs 80% in participants who received SOF and RBV [50]. SOF/VEL with and without RBV was evaluated in 267 HCV genotype 1–6–infected individuals with Child-Pugh class B decompensated cirrhosis [51]. SVR rates were 83% for SOF/VEL for 12 weeks, 94% with SOF/VEL plus RBV for 12 weeks, and 86% SOF/VEL for 24 weeks.

GRAZOPREVIR/ELBASVIR

Grazoprevir and elbasvir (GZR/EBR) are inhibitors of the NS3 and NS5A viral enzymes, respectively. GZR/EBR is available as a once-daily coformulated tablet that is approved for treatment of HCV genotype 1 or 4 infection in adults [52]. The typical treatment duration is 12 weeks. However, individuals with genotype 1a infection and preexisting NS5A viral variants receive GZR/EBR in combination with RBV for 16 weeks.

The bioavailability of EBR is 30%. GZR bioavailability ranges from 10% to 40%. Administration of GZR/EBR with a high-fat (900 kcal, 500 kcal from fat) meal to healthy subjects results in decreases in EBR AUC and Cmax of approximately 11% and 15%, respectively, and increases in GZR AUC and Cmax of approximately 1.5-fold and 2.8-fold, respectively [52]. GZR is at least 98% protein bound and EBR is >99% bound [52]. GZR and EBR are hepatically metabolized and <1% of GZR and EBR are renally eliminated. For the pharmacokinetic properties of GZR/EBR, refer to Table 1. GZR is a substrate for CYP3A4, P-gp, and OATP1B. GZR is also known to be an inhibitor of CYP3A4, UGT1A1, and BCRP. EBR is a substrate for CYP3A4 and P-gp and an inhibitor of BCRP and P-gp. GZR exposures are increased 62% in those with mild (Child-Pugh class A) and 388% in those with moderate (Child-Pugh class B) hepatic impairment relative to those with no hepatic impairment. GZR/EBR is contraindicated in Child-Pugh class B or C decompensated cirrhosis. Of note, EBR with a reduced dose of GZR (50 mg) was evaluated in a study of 30 individuals with decompensated cirrhosis with good efficacy and tolerability [53], but a 50-mg GZR formulation is not available commercially. Total concentrations of EBR are 24% and 14% lower in patients with mild and moderate hepatic insufficiency, respectively. As with some of the other hepatically metabolized DAAs, GZR/EBR AUCs are increased by 65% and 86%, respectively, in those with eGFR < 30 mL/minute/1.73 m2 not receiving dialysis. This increase is not expected to have clinical relevance, however, and in fact this regimen has demonstrated good efficacy and tolerability in 226 HCV-infected individuals with renal impairment [54]. GZR and EBR pharmacokinetics in individuals with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis are comparable to individuals without hepatic impairment, presumably because dialysis clears the uremia, parathyroid hormone, or cytokines, which contribute to impaired hepatic metabolism.

In terms of being perpetrators in drug interactions, pravastatin (OATP1B1 substrate) and rosuvastatin (OATP1B1 and BCRP substrate) exposures are increased 33% and 126%, respectively, by GZR/EBR [52]. No adjustment of pravastatin is necessary, but the rosuvastatin dose should not exceed 10 mg daily with GZR/EBR. In terms of being victims of drug interactions, OATP1B1 inhibitors significantly raise GZR exposures. Single-dose rifampin (OATP1B1 inhibitor) raises GZR AUC by 8- to 10-fold and cyclosporine (OATP/P-gp/MRP2 inhibitor) raises the GZR AUC by 15-fold. Thus, coadministration of GZR/EBR with rifampin or cyclosporine is not recommended. GZR is also susceptible to potent CYP3A inhibitors. Ketoconazole (CYP3A4 inhibitor) increases GZR AUC by 3-fold [55, 56]. EBR is also a victim of drug interactions; when administered with ketoconazole (CYP3A4 inhibitor), the EBR AUC increases by 80% [52]. Coadministration of GZR/EBR with ketoconazole is not recommended.

Given the propensity for OATP1B1- and CYP3A-mediated interactions, ritonavir- or cobicistat-boosted protease inhibitors and efavirenz cannot be used with GZR/EBR. In healthy volunteers, GZR and EBR are increased 10.6-fold and 4.76-fold, respectively, by ritonavir-boosted atazanavir; 7.5-fold and 1.66-fold, respectively, by ritonavir-boosted darunavir; and 12.86-fold and 3.71-fold, respectively, by ritonavir-boosted lopinavir. GZR and EBR are reduced 83% and 54%, respectively, with efavirenz [52, 57]. Tenofovir is increased 34% by EBR. Integrase inhibitors and rilpivirine do not interact with GZR/EBR. Figure 2 provides a summary of drug interactions with GZR/EBR and ARVs. This table is updated regularly and is available through the “Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C” guidance at www.hcvguidelines.org [7].

GZR/EBR was evaluated in 218 treatment-naive patients with chronic HCV genotype 1, 4, or 6 infection and HIV coinfection. This was a nonrandomized, phase 3, open-label, single-arm trial, and 16% of participants had cirrhosis. All patients in this study received GZR 100 mg plus EBR 50 mg in a fixed-dose combination for 12 weeks. In this study, 211 of the 218 patients were receiving ARV consisting of abacavir/lamivudine or TDF/emtricitabine with either raltegravir, dolutegravir, or rilpivirine. SVR was achieved by 96% of patients in this study [58]. The C-WORTHY trial included 59 treatment-naive, noncirrhotic individuals with genotype 1 HCV and HIV coinfection. These patients received GZR 100 mg plus EBR 50 mg for 12 weeks with or without RBV, while continuing on their ARV regimen with dual nucleoside or nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors and raltegravir. SVR rates were 97% and 87% with and without RBV, respectively [59].

PARITAPREVIR, RITONAVIR, OMBITASVIR, AND DASABUVIR (PrOD)/RITONAVIR-BOOSTED PARITAPREVIR AND OMBITASVIR (PrO)

Ombitasvir is a potent NS5A inhibitor, paritaprevir is a potent NS3 protease inhibitor, and dasabuvir is a nonnucleoside NS5B polymerase inhibitor [60]. This combination (PrOD) is used for the treatment of HCV genotype 1. PrOD is administered for 12 weeks to patients with genotype 1b regardless of cirrhosis status. However, in individuals with genotype 1a, RBV is used with PrOD. Noncirrhotic individuals with genotype 1a receive 12 weeks of treatment and cirrhotic individuals receive 24 weeks of PrOD plus RBV. PrO is used with RBV, but without dasabuvir, for 12 weeks for the treatment of individuals with genotype 4 disease [60, 61]. Ritonavir is used in this combination to pharmacokinetically enhance or “boost” the exposures of paritaprevir via inhibition of CYP3A. Ritonavir has no HCV activity. Ritonavir, paritaprevir, and ombitasvir are coformulated [60].

The absolute bioavailability of ombitasvir, paritaprevir, and ritonavir is unknown. The absolute bioavailability of dasabuvir is approximately 70%. Moderate- and high-fat meals increase exposures of all 4 components, and the treatment is approved for administration with a meal. Protein binding is high for all 4 drugs: ombitasvir 99.9%, paritaprevir 97%–98.6%, ritonavir >99%, and dasabuvir >99.5% [60]. See Table 1 for additional information on the pharmacokinetic properties of these agents. Paritaprevir is a substrate for CYP3A4 and, to a lesser extent, CYP3A5; it also inhibits CYP2C8. Paritaprevir is also a substrate for the transporters P-gp, OATP1B1, and BCRP and inhibits P-gp, OATP1B1/1B3, and BCRP. Ombitasvir is not a substrate for any CYP enzymes but is a substrate for P-gp. Ombitasvir inhibits CYP2C8 and UGT1A1, but does not induce or inhibit any transporters. Dasabuvir is metabolized by CYP2C8 and CYP3A and inhibits UGT1A1. Dasabuvir is a substrate for P-gp and has also been shown to inhibit BCRP [61]. Paritaprevir exposures are increased 62% and 945% in individuals with Child-Pugh B and C cirrhosis, respectively. There were reports of hepatic decompensation, hepatic failure, and death in patients with advanced liver disease receiving PrOD. Thus, it should be avoided in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Ombitasvir pharmacokinetics are not significantly altered in renal impairment, but paritaprevir, dasabuvir, and ritonavir exposures are increased with worsening renal function. This is presumed to be due to impairment of hepatic metabolism with poor renal function. PrOD has been studied in noncirrhotic HCV-infected individuals with eGFR < 30 mL/minute/1.73 m2, with good efficacy [62]. PrOD is a potential treatment option for individuals with genotype 1b disease and renal impairment, but RBV is difficult to tolerate, so PrOD may not be ideal for individuals with genotype 1a infection.

In terms of acting as perpetrators of interactions, omeprazole (a CYP2C19 substrate) AUC is reduced 38% by PrOD. Rosuvastatin (substrate for OATP1B1 and BCRP) and pravastatin (substrate for OATP1B1) exposures are increased 159% and 82%, respectively [63]. Low doses of pravastatin and rosuvastatin should be used while on PrOD. PrOD increases ketoconazole AUC by 2-fold and this combination is contraindicated. Ethinyl estradiol–containing oral contraceptives should be avoided with PrOD or PrO because liver enzyme elevations were noted in a drug–drug interaction study of this combination in healthy volunteers. Progestin-containing oral contraceptives may be used [63]. PrOD and PrO are contraindicated with drugs that are highly dependent on CYP3A for clearance, moderate or strong inducers of CYP3A, and strong inducers or inhibitors of CYP2C8. In terms of acting as victims of interactions, ketoconazole (a CYP3A inhibitor) increases ombitasvir, paritaprevir, and dasabuvir by 17%, 98%, and 42%, respectively. Gemfibrozil (a potent CYP2C8 inhibitor) increases dasabuvir exposures by 11-fold. Carbamazepine (CYP3A and P-gp inducer) reduces ombitasvir, paritaprevir, and dasabuvir by 31%, 70%, and 70%, respectively. Many interactions are similar with PrO and PrOD [64], but not all. Refer to the product labeling and www.hep-druginteractions.org for up-to-date information on drug interactions with PrOD and PrO.

PrOD has been studied with several ARV agents. Atazanavir (300 mg once daily) can be given with PrOD, but it should be administered simultaneously with the PrO. The separate ritonavir booster is not needed as PrOD contains a booster. In healthy volunteers, PrOD reduced darunavir trough concentrations by 48% with once-daily ritonavir-boosted darunavir and 43% with twice daily ritonavir-boosted darunavir. An ongoing study (NCT01939197) is evaluating the efficacy of PrOD with ritonavir-boosted darunavir. Until these data are available, this combination should be avoided. Without dasabuvir, however (ie, PrO), the decrease in darunavir troughs is not as pronounced. Because lopinavir is already coformulated with ritonavir, it cannot be used with PrOD, which also contains ritonavir. Rilpivirine AUC is increased 225% by PrOD [60]. This is concerning due to potential QTc prolongation with increased rilpivirine exposures; thus, the combination should be avoided. A study of efavirenz and PrOD in healthy volunteers was prematurely discontinued due to toxicities. Dolutegravir can be used with PrOD. The dolutegravir exposures are increased, but are still within the therapeutic range for the drug [65]. Figure 2 provides a summary of drug interactions with PrOD and PrO and ARVs. This table is updated regularly and is available through the “Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C” guidance at www.hcvguidelines.org [7].

Part 1a of the TURQUOISE-I trial included 63 treatment-naive patients (19% with cirrhosis) with HIV coinfection who received either 12 or 24 weeks of PrOD plus RBV [66]. All patients received dual nucleos(t)ide therapy with raltegravir or ritonavir-boosted atazanavir. SVR rates were 94% and 91% with 12 and 24 weeks of treatment, respectively [66].

RIBAVIRIN

RBV is a purine nucleoside analogue. Oral RBV is used in combination with DAAs for the treatment of chronic HCV infection in certain scenarios including in combination with SOF for genotype 2 disease, with SOF/LDV or SOF/DCV in the setting of decompensated cirrhosis, with PrO or PrOD in patients with genotype 1a or 4 disease, or in combination with GZR/EBR in individuals with baseline NS5A resistance mutations. RBV dosing is typically weight based. Individuals weighing <75 kg receive 1000 mg daily and those weighing at least 75 kg receive 1200 mg daily. The dose is often divided and given twice daily. The efficacy and safety of RBV when combined with various DAAs was summarized in prior sections. Host cell enzymes phosphorylate RBV to mono-, di-, and triphosphate derivatives. The exact mechanism(s) of action of RBV and/or its phosphorylated derivatives in vivo are unknown, but several immunomodulatory and antiviral effects have been observed in vitro including (1) inhibiting the HCV RNA–dependent RNA polymerase, (2) depleting guanosine triphosphate (and thus nucleic acid synthesis in general) through inhibition of inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase, (3) enhancing viral mutagenesis, (4) converting the T-helper cell phenotype from 2 to 1, (4) inducing interferon-stimulated genes, and (5) modulating natural killer cell response [67, 68].

The absolute bioavailability of RBV is 64%. RBV concentrations are increased with a high-fat meal and decreased with purine-rich foods such as margarine, tuna, ham, or whole milk [69, 70]. RBV is not protein bound, and 61% is recovered in the urine. RBV is a substrate for the nucleoside uptake transporters (ENT1, CNT2, and CNT3) and thus is widely distributed throughout the body. RBV is not dose-adjusted for hepatic impairment, but for renal impairment the dose of RBV must be reduced. RBV is given in alternating daily doses of 200 mg and 400 mg in individuals with an eGFR of 30–50 mL/minute/1.73 m2, and 200 mg orally once daily for individuals with an eGFR <30 mL/minute/1.73 m2 or receiving hemodialysis [70]. Despite these dose reductions, many individuals with renal impairment develop hemolytic anemia.

RBV has minimal drug interactions, but should not be used with the HIV nucleoside analogue didanosine. RBV increases formation of the triphosphorylated form of didanosine, which raises the risk of mitochondrial toxicity [71]. Zidovudine and RBV both cause anemia, so this combination should also be avoided.

CONCLUSIONS

As with HCV-monoinfected persons, the vast majority of individuals with HIV/HCV coinfection can achieve SVR with all oral DAAs. The primary consideration in treating this population is identification and management of drug interactions. In general, current therapies have well-characterized pharmacology and manageable drug interaction profiles, but opportunities remain to determine optimal doses and combinations of the DAAs in individuals with HIV coinfection. A comprehensive understanding of the pharmacology and interaction potential of DAAs allows for informed and improved use of these agents.

Notes

Financial support. This activity is accredited by the University of Cincinnati, provided by the Chronic Liver Disease Foundation, and supported by an educational grant from Merck & Co. J. J. K. has received financial support from the National Institutes of Health (grant number R01 DA040499).

Supplement sponsorship. This article appears as part of the supplement “Management of Hepatitis C/HIV Coinfection in the Era of Highly Effective HCV Direct-Acting Antiviral Therapy.” This supplement is sponsored through an educational grant from Merck & Co. The activity is accredited by the University of Cincinnati and provided by the Chronic Liver Disease Foundation.

Potential conflict of interest. J. J. K. has received grants from Janssen, ViiV Healthcare, Merck, and other from Gilead Sciences. C. E. M. and J. J. K. have received honoraria from the Chronic Liver Disease Foundation. Both authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Rockstroh JK, Mocroft A, Soriano V et al. Influence of hepatitis C virus infection on HIV-1 disease progression and response to highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis 2005; 192:992–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alter MJ. Hepatitis C virus infection in the United States. J Hepatol 1999; 31(suppl 1):88–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinez-Sierra C, Arizcorreta A, Diaz F et al. Progression of chronic hepatitis C to liver fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients coinfected with hepatitis C virus and human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis 2003; 36:491–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen JY, Feeney ER, Chung RT. HCV and HIV co-infection: mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 11:362–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benhamou Y, Bochet M, Di Martino V et al. Liver fibrosis progression in human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus coinfected patients. The Multivirc Group. Hepatology 1999; 30:1054–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lo Re V III, Kallan MJ, Tate JP et al. Hepatic decompensation in antiretroviral-treated patients co-infected with HIV and hepatitis C virus compared with hepatitis C virus-monoinfected patients: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2014; 160:369–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.AASLD/IDSA HCV Guidance Panel. Hepatitis C guidance: AASLD-IDSA recommendations for testing, managing, and treating adults infected with hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 2015; 62:932–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.European Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol 2014; 60:392–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holmes JA, Thompson AJ. Interferon-free combination therapies for the treatment of hepatitis C: current insights. Hepat Med 2015; 7:51–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perez-Olmeda M, Nunez M, Romero M et al. Pegylated IFN-alpha2b plus ribavirin as therapy for chronic hepatitis C in HIV-infected patients. AIDS 2003; 17:1023–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wyles DL, Ruane PJ, Sulkowski MS et al. Daclatasvir plus sofosbuvir for HCV in patients coinfected with HIV-1. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:714–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wyles DL, Sulkowski MS, Dieterich D. Management of hepatitis C/HIV coinfection in the era of highly effective hepatitis C virus direct-acting antiviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 63(suppl 1):3–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denning J, Cornpropst M, Flach SD, Berrey MM, Symonds WT. Pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of GS-9851, a nucleotide analog polymerase inhibitor for hepatitis C virus, following single ascending doses in healthy subjects. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013; 57:1201–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirby BJ, Symonds WT, Kearney BP, Mathias AA. Pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, and drug-interaction profile of the hepatitis C virus NS5B polymerase inhibitor sofosbuvir. Clin Pharmacokinet 2015; 54:677–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sovaldi (sofosbuvir). Prescribing information. Foster City, CA: Gilead Sciences, 2015.

- 16.Harvoni (ledipasvir and sofosbuvir). Prescribing information. Foster City, CA: Gilead Sciences, 2015.

- 17.Back DJ, Burger DM. Interaction between amiodarone and sofosbuvir-based treatment for hepatitis C virus infection: potential mechanisms and lessons to be learned. Gastroenterology 2015; 149:1315–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirby B, Mathias A, Rossi S, Moyer C, Shen G, Kearney B. No clinically significant pharmacokinetic interactions between sofosbuvir (GS-7977) and HIV antiretrovirals Atripla, rilpivirine, darunavir/ritonavir, or raltegravir in healthy volunteers. In: 63rd Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, Boston, MA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sulkowski MS, Naggie S, Lalezari J et al. Sofosbuvir and ribavirin for hepatitis C in patients with HIV coinfection. JAMA 2014; 312:353–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Molina JM, Orkin C, Iser DM et al. Sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for treatment of hepatitis C virus in patients co-infected with HIV (PHOTON-2): a multicentre, open-label, non-randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet 2015; 385:1098–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeuzem S, Hezode C, Bronowicki JP et al. Daclatasvir plus simeprevir with or without ribavirin for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection. J Hepatol 2016; 64:292–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daklinza (daclatasvir). Prescribing information. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb, 2015.

- 23.Eley T, You X, Wang R et al. Daclatasvir: overview of drug–drug interactions with antiretroviral agents and other common concomitant drugs. In: HIV DART, Miami, FL, 9–12 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bifano M, Hwang C, Oosterhuis B et al. Assessment of pharmacokinetic interactions of the HCV NS5A replication complex inhibitor daclatasvir with antiretroviral agents: ritonavir-boosted atazanavir, efavirenz and tenofovir. Antivir Ther 2013; 18:931–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gandhi Y, Adamczyk R, Wang R et al. Assessment of drug–drug interactions between daclatasvir and darunavir/ritonavir or lopinavir/ritonavir [abstract 80] In: 16th International Workshop on Clinical Pharmacology of HIV and Hepatitis Therapy, Washington, DC, 26–28 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song I, Jerva F, Zong J et al. Evaluation and drug interactions between dolutegravir and daclatasvir in healthy volunteers [abstract 79]. In: 16th International Workshop on Clinical Pharmacology of HIV and Hepatitis Therapy, Washington, DC, 26–28 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garimella T, Gandhi Y, Wang R et al. Daclatasvir exposure alone does not explain HCV relapse in HIV-HCV coinfected patients receiving daclatasvir plus sofosbuvir with ritonavir-boosted darunavir in the ALLY-2 study [ abstract 728] In: AASLD LiverLearning, 14 November 2015; 109972. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Terrault N, Zeuzem S, Di Bisceglie A et al. Treatment outcomes with 8, 12 and 24 week regimens of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir for the treatment of hepatitis C infection: analysis of a multicenter prospective, observational study. In: Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, San Francisco, CA, 13–17 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mascolini M. Impact of food and antacids on levels of ledipasvir and sofosbuvir. In: 15th International Workshop on Clinical Pharmacology of HIV and Hepatitis Therapy, Washington, DC, 19–21 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30.German P, Pang PS, Fang L et al. Drug–drug interaction profile of the fixed dose combination tablet ledipasvir/sofosbuvir. In: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, Boston, MA, 7–11 November 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kirby B. Transporters: role in clinical development of HCV compounds. In: Presentation at the 15th International Workshop on Clinical Pharmacology of HIV and Hepatitis Therapy, Washington, DC, 19–21 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 32.German P, Pang PS, West S et al. Drug interaction between direct acting anti-HCV antivirals sofosbuvir and ledipasvir and HIV antiretrovirals [abstract 06] In: 15th International Workshop on Clinical Pharmacology of HIV and Hepatitis Therapy Washington, DC, 19–21 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 33.German P, Garrison K, Pang PS et al. Drug interactions between the anti-HCV regimen ledipasvir/sofosbuvir and ritonavir boosted protease inhibitors plus emtricitabine/tenofovir DF. In: 22nd Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Seattle, WA, 23–26 February 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garrison KL, Custodi J, Pang PS et al. Drug interactions between anti-HCV antivirals ledipasvir/sofosbuvir and integrase strand transfer inhibitor-based regimens [abstract 71]. In: 16th International Workshop on Clinical Pharmacology of HIV and Hepatitis Therapy, Washington, DC, 26–28 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Osinusi A, Townsend K, Kohli A et al. Virologic response following combined ledipasvir and sofosbuvir administration in patients with HCV genotype 1 and HIV co-infection. JAMA 2015; 313:1232–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naggie S, Cooper C, Saag M et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for HCV in patients coinfected with HIV-1. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:705–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olysio (simeprevir). Prescribing information. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Therapeutics, 2015.

- 38.Ouwerkerk-Mahadevan S, Alexandru S, Peeters M et al. Summary of pharmacokinetic drug-drug interactions for simeprevir (TMC435), a hepatitis C virus Ns3/4A protease inhibitor. In: 14th European AIDS Conference, Brussels, Belgium, 16–19 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kwo P, Gitlin N, Nahass R et al. A phase 3, randomised, open-label study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of 12 and 8 weeks of simeprevir (SMV) plus sofosbuvir (SOF) in treatment-naive and -experienced patients with chronic HCV genotype 1 infection without cirrhosis: OPTIMIST-1. In: European Association for the Study of the Liver, Vienna, Austria, 22–26 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lawitz E, Matusow G, DeJesus E et al. A phase 3, open-label, single-arm study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of 12 weeks of simeprevir (SMV) plus sofosbuvir (SOF) in treatment-naive or -experienced patients with chronic HCV genotype 1 infection and cirrhosis: OPTIMIST-2. In: European Association for the Study of the Liver, Vienna, Austria, 22–26 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pianko S, Flamm SL, Shiffman ML et al. Sofosbuvir plus velpatasvir combination therapy for treatment-experienced patients with genotype 1 or 3 hepatitis C virus infection: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2015; 163:809–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mogalian E, Lutz J, Osinusi A et al. Effect of food and acid reducing agents on the relative bioavailability and pharmacokinetics of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir fixed dose combination tablet. In: American Society for Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, San Diego, CA, 8–12 March 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mathias A. Clinical pharmacology of DAAs for HCV: what's new and what's in the pipeline. In: 14th International Workshop on Clinical Pharmacology of HIV Therapy, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 24 April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mogalian E, German P, Kearney BP et al. Use of multiple probes to assess transporter- and cytochrome P450-mediated drug-drug interaction potential of the pangenotypic HCV NS5A inhibitor velpatasvir. Clin Pharmacokinet 2015; 55:605–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mogalian E, Mathias A, Brainard D et al. The pharmacokinetics of GS-5816, a pan-genotypic HCV NS5A inhibitor, in HCV-uninfected subjects with moderate and severe hepatic impairment. J Hepatol 2014; 60:S317. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mogalian E, Mathias A, Brainard D et al. The pharmacokinetics of GS-5816, a pangenotypic HCV-specific NS5A inhibitor, in HCV-uninfected subjects with severe renal impairment. EASL–the International Liver Congress 2015. In: 50th annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of the Liver, Vienna, Austria, 22–26 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mogalian E, Stamm L, Osinusi A et al. Drug-drug interaction studies between hepatitis C virus antivirals sofosbuvir and velpatasvir (GS-5816) and HIV antiretroviral therapies. In: 66th Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, San Francisco, CA, 13–17 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Feld JJ, Jacobson IM, Hezode C et al. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for HCV genotype 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 infection. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:2599–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sulkowski M, Brau N, Lawitz E et al. A randomized controlled trial of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir fixed-dose combination for 12 weeks compared to sofosbuvir with ribavirin for 12 weeks in genotype 2 HCV-infected patients: the phase 3 ASTRAL-2 study. In: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, San Francisco, 13–17 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Foster GR, Afdhal N, Roberts SK et al. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for HCV genotype 2 and 3 infection. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:2608–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Curry MP, O'Leary JG, Bzowej N et al. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for HCV in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:2618–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zepatier (elbasvir/grazoprevir). Prescribing information Merck; and Co, Inc, NJ: Whitehouse Station, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jacobson IM, Poordad F, Firpi-Morell R et al. Efficacy and safety of grazoprevir and elbasvir in hepatitis C genotype 1–infected patients with Child-Pugh class B cirrhosis (C-SALT part A). In: 50th Annual Meeting of the European Association for the Study of the Liver, Vienna, Austria, 22–26 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roth D, Nelson DR, Bruchfeld A et al. Grazoprevir plus elbasvir in treatment-naive and treatment-experienced patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection and stage 4–5 chronic kidney disease (the C-SURFER study): a combination phase 3 study. Lancet 2015; 386:1537–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yeh W, Marshall W, Caro L et al. Pharmacokinetic interaction of HCV NS5A inhibitor MK-8742 and ketoconazole in healthy subjects. In: 15th International Workshop on Clinical Pharmacology of HIV and Hepatitis Therapy, Washington, DC, 19–21 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Caro L, Talaty J, Guo Z et al. Pharmacokinetic interaction between the HCV protease inhibitor MK-5172 and midazolam, pitavastatin, and atorvastatin in healthy volunteers [abstract 477]. Hepatology 2013;58(4 [suppl] AASLD Abstracts):437A. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yeh W. Drug-drug interactions with grazoprevir/elbasvir: practical considerations for the care of HIV/HCV co-infected patients. In: 16th International Workshop on Clinical Pharmacology of HIV and Hepatitis Therapy, Washington, DC, 28 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rockstroh JK, Nelson M, Katlama C et al. Efficacy and safety of grazoprevir (MK-5172) and elbasvir (MK-8742) in patients with hepatitis C virus and HIV co-infection (C-EDGE CO-INFECTION): a non-randomised, open-label trial. Lancet HIV 2015; 2:e319–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sulkowski M, Hezode C, Gerstoft J et al. Efficacy and safety of 8 weeks versus 12 weeks of treatment with grazoprevir (MK-5172) and elbasvir (MK-8742) with or without ribavirin in patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 mono-infection and HIV/hepatitis C virus co-infection (C-WORTHY): a randomised, open-label phase 2 trial. Lancet 2015; 385:1087–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Viekira Pak (ombitasvir, paritaprevir, and ritonavir tablets; dasabuvir tablets). Prescribing information. North Chicago, IL: Abbvie, Inc, 2015. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Technivie (ombitasvir, paritaprevir, and ritonavir tablets). Prescribing information. North Chicago, IL: Abbvie, Inc, 2015.

- 62.Pockros PJ, Reddy KR, Mantry PS et al. Safety of ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir plus dasabuvir for treating HCV GT1 infection in patients with severe renal impairment or end-stage renal disease: the Ruby-I study. In: European Association for the Study of the Liver, Vienna, Austria, 22–26 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Menon RM, Badri PS, Wang T et al. Drug-drug interaction profile of the all-oral anti-hepatitis C virus regimen of paritaprevir/ritonavir, ombitasvir, and dasabuvir. J Hepatol 2015; 63:20–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Badri PS, Dutta S, Wang H et al. Drug interactions with the direct-acting antiviral combination of ombitasvir and paritaprevir/ritonavir (2D regimen). Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 60:105–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Khatri A, Wang T, Wang H et al. Drug-drug interactions of the direct-acting antiviral regimen of ABT-450/r, ombitasvir, and dasabuvir with emtricitabine + tenofovir, raltegravir, rilpivirine, and efavirenz [abstract 483]. In: 54th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy (ICAAC) Washington, DC, 5–9 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sulkowski MS, Eron JJ, Wyles D et al. Ombitasvir, paritaprevir co-dosed with ritonavir, dasabuvir, and ribavirin for hepatitis C in patients co-infected with HIV-1:a randomized trial. JAMA 2015; 313:1223–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Werner JM, Serti E, Chepa-Lotrea X et al. Ribavirin improves the IFN-gamma response of natural killer cells to IFN-based therapy of hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology 2014; 60:1160–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thomas E, Ghany MG, Liang TJ. The application and mechanism of action of ribavirin in therapy of hepatitis C. Antivir Chem Chemother 2013; 23:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li L, Koo SH, Limenta LM et al. Effect of dietary purines on the pharmacokinetics of orally administered ribavirin. J Clin Pharmacol 2009; 49:661–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Copegus (ribavirin). Prescribing information. South San Francisco, CA: Genentech, Inc, 2015.

- 71.Salmon-Ceron D, Chauvelot-Moachon L, Abad S, Silbermann B, Sogni P. Mitochondrial toxic effects and ribavirin. Lancet 2001; 357:1803–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]