Abstract

Background & objectives:

There is a paucity of data available on genetic biodiversity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from central India. The present study was carried out on isolates of M. tuberculosis cultured from diagnostic clinical samples of patients from Bhopal, central India, using spoligotyping as a method of molecular typing.

Methods:

DNA was extracted from 340 isolates of M. tuberculosis from culture, confirmed as M. tuberculosis by molecular and biochemical methods and subjected to spoligotyping. The results were compared with the international SITVIT2 database.

Results:

Sixty five different spoligo international type (SIT) patterns were observed. A total of 239 (70.3%) isolates could be clustered into 25 SITs. The Central Asian (CAS) and East African Indian (EAI) families were found to be the two major circulating families in this region. SIT26/CAS1_DEL was identified as the most predominant type, followed by SIT11/EAI3_IND and SIT288/CAS2. Forty (11.8%) unique (non-clustered) and 61 (17.9%) orphan isolates were identified in the study. There was no significant association of clustering with clinical and demographic characteristics of patients.

Interpretation & conclusions:

Well established SITs were found to be predominant in our study. SIT26/CAS1_DEL was the most predominant type. However, the occurrence of a substantial number of orphan isolates may indicate the presence of active spatial and temporal evolutionary dynamics within the isolates of M. tuberculosis.

Keywords: Genetic diversity, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, polymorphism, spoligotyping

The global annual incidence of tuberculosis (TB) is 9.6 million cases, of which 2.2 million cases (one fifth of the global incidence) are from India1,2. The propagation success of this disease is directly linked to the infectivity of the organism, which is spread rapidly through aerosols produced by TB patients with active pulmonary disease. Molecular typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates provides a method for studying the transmission dynamics and the spatial and temporal evolutionary genetics of M. tuberculosis strains in different geographical areas. Data collected using these methods can provide valuable information that could eventually impact TB control measures.A pilot study to identify the genetic biodiversity of isolates of M. tuberculosis using spoligotyping as a method of molecular typing, found several unique and previously uncharacterized types of M. tuberculosis, in addition to well established ancestral clones3. The present study was undertaken to examine a much larger number of M. tuberculosis isolates from Bhopal (Madhya Pradesh, India), and its neighbourhood to identify the predominant as well as unique spoligotype patterns of the circulating isolates of M. tuberculosis.

Material & Methods

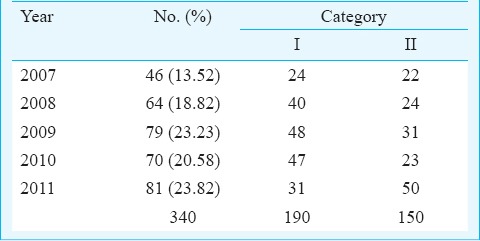

Sampling and specimens: A convenience sample of 340 isolates of M. tuberculosis cultured from diagnostic clinical samples of patients who attended the clinics of the Bhopal Memorial Hospital and Research Centre (BMHRC), Bhopal, and district microscopy centres of various districts of Madhya Pradesh from March 2007 to November 2011, was included in the study. Among these patients, 241 were male and 99 were female patients. Three hundred and twenty clinical samples were from pulmonary samples [251 sputa, 46 bronchial aspirates, 18 bronchoalveolar lavage fluids (BAL), 3 bronchial washings, 1 bronchial brushing in saline and 1 secretion collected through an endotracheal tube]. There were 20 extrapulmonary specimens (7 pleural fluids, 6 pus, 2 fine needle aspirates from lymph nodes, 1 CSF, 1 urine, and 3 granulation tissue materials). One hundred and ninety patients belonged to Category I (new treatment group) with new pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis. The remaining 150 belonged to Category II (previously treated group) with treatment failure (Table I) as per Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme (RNTCP) guidelines.

Table I.

Distribution of isolates by year and category of treatment received

Culture and identification: At BMHRC, all specimens were processed for culture by standard sodium hydroxide-N-acetyl-L-cystein (NaOH-NALC) method for digestion and decontamination4. Sediments were inoculated on two Lowenstein-Jensen slants (L-J slants) and incubated at 37° C till growth appeared on the slants or till two months, whichever was earlier. The organisms were identified as M. tuberculosis using rRNA directed DNA hybridization assay (GenProbe, bioMérieux, France) after demonstration of absence of growth on L-J slants incorporated with P-nitrobenzoic acid, a positive niacin accumulation test, a positive nitrate reduction test and a negative catalase test.

DNA extraction and spoligotyping: DNA from M. tuberculosis isolates was extracted using QIAamp® DNA Mini kit (QIAGEN®, Germany) following manufacturer's instructions. Spoligotyping was carried out by using a commercial kit (Ocimum Biosolutions, Hyderabad) at the National JALMA Institute for Leprosy and Other Mycobacterial Diseases, Agra. As per the manufacturer's protocol, the extracted DNA was subjected to PCR (initial denaturation at 96°C for 3 min, followed by 25 cycles of 1 min each at 96°C, 1 min at 55°C and 30 seconds at 72°C, and final cycle of extension at 96°C for 5 min) to amplify the direct repeat region and interspersed known spacers region using specific biotinylated primers. PCR products were hybridized using streptavidine-conjugate with 43 known spacer oligonucleotides that were covalently bound to an activated membrane. Hybridization signals were recorded by enhanced chemiluminescence detection system and blotted in reverse on an X-ray film. Distilled water was used as negative control and H37Rv obtained from National JALMA Institute for Leprosy and Other Mycobacterial Diseases was used as positive control. Absence and presence of spacer oligonucleoides were documented in the form of binary code that was converted into octal code. The results were analyzed using the SITVIT2 database of Institute Pasteur de Guadeloupe5 to locate families of spoligotypes. When more than one isolate was found to have the same SIT, it was referred to as a cluster, and if only one isolate was found to have a specific SIT, it was referred to as unique, as per the common usage of the term as used earlier6-9. At the time of comparison, the database consisted of a total of 7105 spoligotype patterns (corresponding to 58,180 clinical isolates) – grouped into 2740 shared-types or spoligotype international types (SIT) containing 53,816 clinical isolates and 4364 orphan patterns. Only 7 per cent of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex isolates worldwide were orphans whereas more than half of SIT clustered isolates (n = 27,059) were restricted to only 24 most prevalent SITs5. An attempt was made to understand the genetic polymorphism of 61 (17.9%) orphan isolates using SpotClust analysis tool10 (http://tbinsight.cs.rpi.edu/run_spotclust.html).

Statistical analysis: Association between demographic characteristics of the individuals (whose samples have been used here) with occurrence of clustered and non-clustered M. tuberculosis Complex isolates was examined using univariate odds ratio. Proportions were compared using Chi-square test and Fisher's exact tests wherever appropriate.

Results

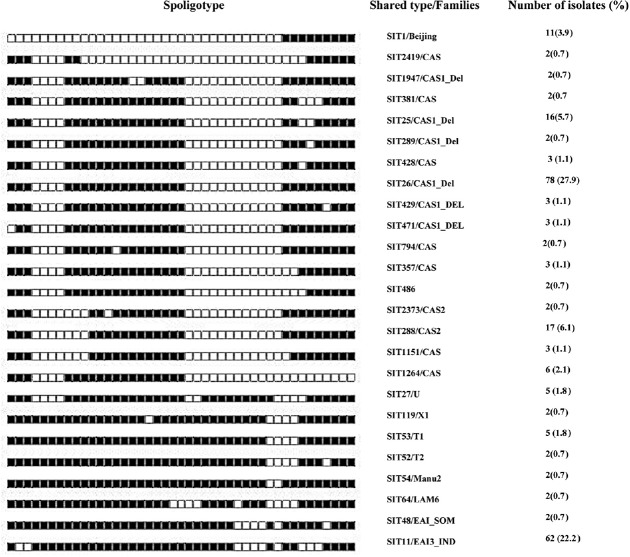

Clinical and demographic characteristics of patients are given in Table II. Of the 340 isolates, 279 (82%) could be identified as belonging to 65 SITs by matching with the SITVIT2 database. However, 61 (17.9%) isolates did not match the database and were referred to as orphan isolates. Two hundred and thirty nine isolates (70.3%) could be clustered into 25 SITs, whereas 40 (11.8%) unique (non-clustered) isolates were detected. The clustered isolates predominantly belonged to Central Asian and East African Indian families. Both these families (including clustered and non-clustered) together accounted for 239 (85.7%) isolates of the total number of families identified. Of the total 239 clustered isolates, there were 169 (70.71%) isolates that belonged to the Central Asian family alone, and the East African Indian family alone had 72 (30.12%) isolates out of the total number of isolates with identified SITs. SIT26/CAS1_DEL was identified as the most predominant type, with 78 isolates (27.9%). The second most predominant type was recognized as SIT11/EAI3_IND, with 62 (22.2%) isolates. SIT288/CAS2 with 17 isolates (6.1%) was the third most predominant SIT. The other clustered SITs were SIT25/CAS1_Del with 16 (5.7%) isolates, SIT1/Beijing with 11 (3.9%) isolates, SIT1264/CAS with six (2.1%) isolates, SIT27/U and SIT53/T1 with five (1.8%) isolates each, SIT1151/CAS, SIT357/CAS, SIT428/CAS, SIT429/CAS1_DEL, SIT471/CAS1_DEL with three (1.1%) isolates each and SIT119/X1, SIT289/CAS1_DEL, SIT381/CAS, SIT48/EAI_SOM, SIT486/CAS, 2SIT52/T2, SIT54/Manu2, SIT64/LAM6, SIT794/CAS, SIT1947/CAS_DEL, SIT2373/CAS2 and SIT2419/CAS with two (0.7%) isolates each (Fig. 1).

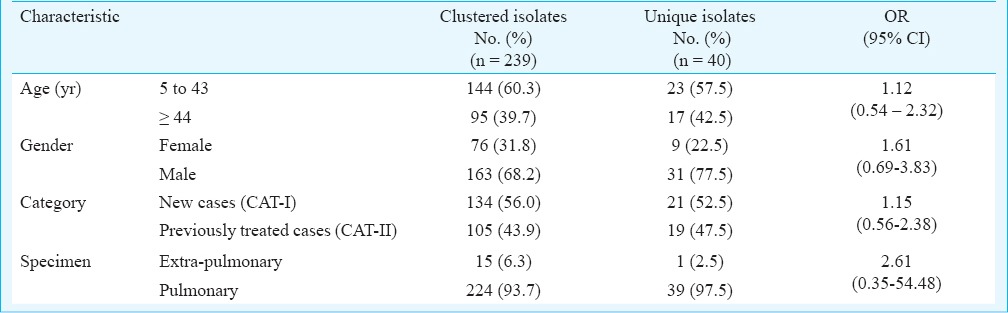

Table II.

Clinical and demographic characteristics in relation to clustering of M. tuberculosis isolates

Fig. 1.

Spoligotype patterns of 239 clustered M. tuberculosis isolates identified by matching with the SITVIT2 database in the study. SIT, spoligotype international type; filled boxes represent positive hybridization while empty boxes represent absence of spacers. Percentages calculated out of 279 typed isolates.

Of the 20 extrapulmonary isolates, 15 (75%) showed clustering. The largest cluster belonged to East African Indian (EAI) lineage. One isolate was unique. On the other hand, of the 320 pulmonary isolates, 224 (70%) showed clustering, while 39 (12.18%) isolates were unique. The largest cluster of isolates from pulmonary samples belonged to the Central Asian (CAS) lineage.

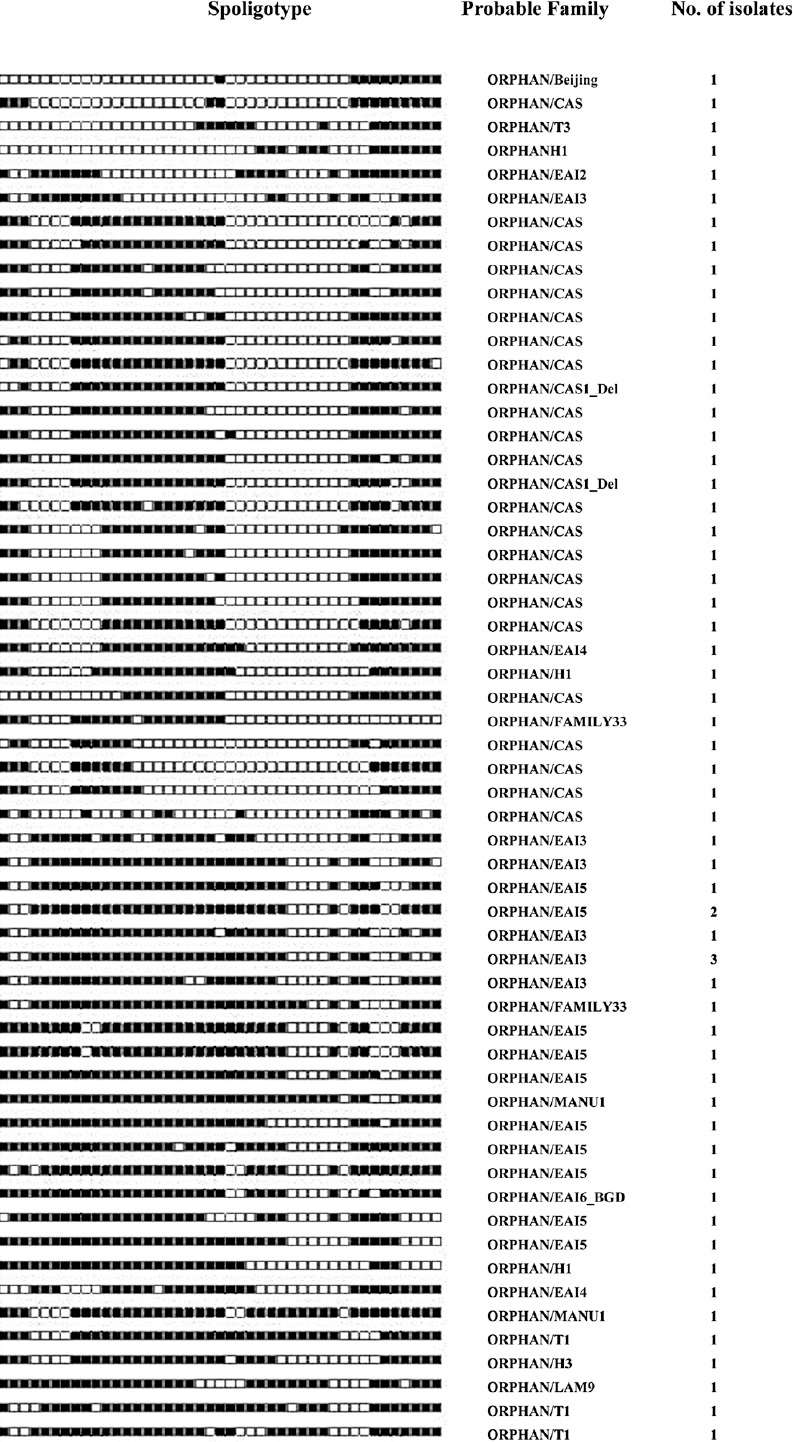

Sixty one isolates with orphan patterns were further analyzed using the SpotClust tool to assign their most probable families. Sixteen most probable families were recognized that included CAS with 24 (39.3%) isolates, EAI5 with 11 (18%), EAI3 with eight (13.1%), T1 with three (4.9%) isolates, EAI4, H1 and FAMILY-33 with two (3.3%) isolates each, Manu 1, T3, H3, Family34, Family36, LAM9, Beijing, EAI2, and EAI6 with one isolate each (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Spoligotypes of 61 orphan isolates not identified in SITVIT2 database by a SIT number and analysed by SpotClust tool.

Discussion

Madhya Pradesh is a large State in the centre of India, with a population of approximately 72.6 million, as per the 2011 census11. There were 52,451 smear positive cases diagnosed in the State between the 4thquarter of 2009 to the 3rd quarter of 20101. This underscores the need to characterize the genetic biodiversity of isolates of M. tuberculosis in this part of the country. The most predominant SIT in our study was found to be SIT26/CAS1_DEL. The predominance of this SIT has been reported from various studies in India, particularly in north India6-9. The second most predominant type was recognized as SIT11/EAI3_IND. This SIT has been reported predominantly from south India12. A study from Kerala reported that majority of the isolates (64.28%) belonged to the ancestral EAI lineage12. The third most predominant type, SIT288/CAS2, has also been reported earlier from northern India5,6,9 and from various other parts of the world including Australia, Belgium, Bangladesh, Germany, U.K., Netherlands, Pakistan Saudi Arabia, Tanzania, USA and South Africa5. Of the other types, SIT27/U, SIT794/CAS, SIT2373/CAS2 and 2419/CAS have not been reported from India in the SITVIT2 database5. However, SIT27/U has been reported earlier from Australia, Germany, U.K., Kenya, Pakistan and USA, SIT794/CAS from Bangladesh, USA, U.K., and Pakistan, SIT2373/CAS2 from Belgium and USA; and SIT2419/CAS from Pakistan and USA5. Forty unique SITs were identified, of which 10 types have not been reported from India in the SITVIT2 database. These include SIT1120/CAS, SIT1401/CAS1_Del, SIT1878/CAS1_Del, SIT247/CAS1_DEL, SIT294/CAS, SIT612/T1, SIT749/CAS_DEL, SIT763/EAI5, SIT95/LAM6 and SIT2151/T4.

When analyzed with SpotClust tool10, 61 (17.9%) orphan isolates demonstrated clustering as well. The high number of isolates designated as “orphan” may be due to the likelihood that these isolates were not typed earlier; or, were typed, but not reported to the SITVIT2 database. On the other hand, this may indicate the possible presence of hitherto unidentified evolutionary forces driving the dynamics of the endemic state of tuberculosis infection in this area.

The occurrence of clustered isolates was not associated with any of the demographic variables like age and gender. Further, it was also seen that previous history of anti-TB treatment and the type of tuberculosis (pulmonary or extra-pulmonary) also were not associated with occurrence of clustered isolates. This was further strengthened by the non-significant odds ratios for the above variables.

This study provides an insight into the genetic biodiversity of isolates of M. tuberculosis circulating in this area. A few SITs were found to be well conserved and ubiquitous. This was in consonance with the finding from a study from south India that revealed that 85.2 per cent of isolates belonged to the ancestral lineage of M. tuberculosis13. This finding, and ours, conforms to the perception that most of the tuberculosis burden in India is due to a few well established clones of M. tuberculosis9,14. Virulence and dissemination potentials of these ancestral isolates are speculated to be ‘low’ as compared to the other ‘aggressive’ ones such as Beijing and LAM, which are expected to be more widespread in future, also in synergy with HIV and diabetes epidemics15.

A study from Mumbai on drug resistant isolates found seven closely related clusters, a cluster with two Beijing-like isolates, and unique spoligotypes (43%). Of the clusters, one with 29 per cent of all the isolates suggested transmission of a dominant resistant clone16. Hence, further studies focusing on polymorphism related to drug resistance would be the next logical step for this study group.

Well established SITs were predominant in our study. SIT26/CAS1_DEL was identified as the most predominant type. A significant number of orphan isolates may indicate the presence of active spatial and temporal evolutionary dynamics within the population of M. tuberculosis isolates studied.

Our study provided preliminary, but essential, information about M. tuberculosis isolates circulating in this region. These results could be used as a reference point to understand the dynamics and changes in the genetic profile of M. tuberculosis isolates in this area following different interventions carried out through the Revised National TB Control Programme (RNTCP). These may also be used as baseline data to assess the success of TB control measures.

Further studies on a larger number of isolates in this region are needed to understand the clinical, genetic and social correlates of the evolution of M. tuberculosis in this geographical area.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the Indian Council of Medical Research for providing financial support.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- 1.TB India 2016, Revised National TB Control Programme, Annual Status Report. New Delhi: Central TB Division, Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Global Tuberculosis Control 2015. 20th ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Desikan P, Chauhan DS, Sharma P, Panwalkar N, Gautam S, Katoch VM. A pilot study to determine genetic polymorphism in Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates in Central India. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2012;30:470–3. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.103774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.New Delhi, India: Central TB Division, Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2009. Apr, Revised National TB Control Programme. Training manual for Mycobacterium tuberculosis culture & drug susceptibility testing. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Demaya C, Liensa B, Burguièrea T, Hilla V, Couvina D, Milleta J, et al. SITVITWEB - A publicly available international multimarker database for studying Mycobacterium tuberculosis genetic diversity and molecular epidemiology. Infect Genet Evol. 2012;12:755–66. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varma-Basil M, Kumar S, Arora J, Angrup A, Zozio T, Banavaliker JN, et al. Comparison of spoligotyping, Mycobacterial interspersed repetitive units typing and IS6110-RFLP in a study of genotypic diversity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Delhi, North India. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2011;106:524–35. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762011000500002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma P, Chauhan DS, Upadhyay P, Faujdar J, Lavania M, Sachan S, et al. Molecular typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from rural area of Kanpur by spoligotyping and Mycobacterial interspersed repetitive units (MIRUs) typing. Infect Genet Evol. 2008;8:621–6. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh UB, Suresh N, Bhanu NV, Arora J, Pant H, Sinha S, et al. Predominant Tuberculosis spoligotypes, Delhi, India. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1138–42. doi: 10.3201/eid1006.030575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh UB, Arora J, Suresh N, Pant H, Rana T, Sola C, et al. Genetic biodiversity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from patients from pulmonary tuberculosis in India. Infect Genet Evol. 2007;7:441–8. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vitol I, Driscoll J, Kreiswirth B, Kurepina N, Bennett KP. Identifying Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strain families using spoligotypes. Infect Genet Evol. 2006;6:491–4. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.New Delhi: National Informatics Centre (NIC), Department of Electronics and Information Technology (DeitY), Ministry of Communications and Information Technology (MoCIT), Government of India; 2011. Census of India, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joseph BV, Soman S, Radhakrishnan I, Hill V, Dhanasooraj D, Kumar RA, et al. Molecular epidemiology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from Kerala, India using IS6110-RFLP, spoligotyping and MIRU-VNTRs. Infect Genet Evol. 2013;16:157–64. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Narayanan N, Gagneux S, Hari L, Tsolaki AG, Rajasekhar S, Narayanan PR, et al. Genomic interrogation of ancestral Mycobacterium tuberculosis from south India. Infect. Genet Evol. 2008;8:474–83. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gutierrez CM, Ahmed N, Willery E, Narayanan S, Hasnain SE, Chauhan DS, et al. Predominance of ancestral lineages of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in India. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1367–74. doi: 10.3201/eid1209.050017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmed N, Ehtesham NZ, Hasnain SE. Ancestral Mycobacterium tuberculosis genotypes in India: Implications for TB control programmes. Infect. Genet Evol. 2009;9:142–6. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mistry NF, Iyer AM, D’souza DTB, Taylor GM, Young DB, Antia NH. Spoligotyping of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Isolates from multiple-drug-resistant tuberculosis patients from Bombay, India. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:2677–80. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.7.2677-2680.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]