Abstract

Background & objectives:

Limited data are available on prescription patterns of the antidepressants from India. We studied antidepressants’ prescription pattern from five geographically distant tertiary psychiatric care centers of the India.

Method:

In this cross-sectional study, all patients who attended outpatients department or were admitted in the psychiatry wards at Lucknow, Chandigarh, Tiruvalla, Mumbai and Guwahati on a fixed day, who were using or had been prescribed antidepressant medications, were included. The data were collected on a unified research protocol.

Results:

A total of 312 patients were included. Mean age was 39±14.28 yr and 149 (47.76%) were females, 277 (87.5%) were outpatients. Among the patients receiving antidepressants, 150 (48.1%) were of diagnoses other than depression. Diabetes mellitus 18 (5.78%) was the most common co-morbid medical illness. A total of 194 (62.2%) patients were using selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) with escitalopram 114 (36.53%) being the most common antidepressant used. Overall, 272 (87.18%) patients were using newer antidepressants. Thirty (9.62%) were prescribed more than one antidepressant; 159 (50.96%) patients were prescribed hypnotic or sedative medications with clonazepam being the most common (n=116; 37.18%).

Interpretation & conclusions:

About half of the patients with diagnoses other than depression were prescribed antidepressants. SSRIs were the most common group and escitalopram was the most common medication used. Concomitant use of two antidepressants was infrequent. Hypnotic and sedatives were frequently prescribed along with antidepressants.

Keywords: Antidepressants, India, prescription pattern, sedatives, SSRIs

Antidepressants are a group of psychotropic medications developed to treat the symptoms of depression. However, these are also used for the pharmacological treatment of a range of psychiatric disorders including anxiety disorders, obsessive compulsive disorders, adjustment disorders, somatoform disorders, eating disorders, impulse control disorders, chronic pain, neuropathic pain, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, etc. Irrespective of the presence or absence of co-morbid depression in these conditions1. There are only minor differences in efficacy among different antidepressants, at least in major depressive disorders, leaving other factors to influence drug selection2. Selection of a suitable antidepressant for a particular patient is done on the basis of many factors including patient's demographic characteristics, illness profile, side effects of the medication, comorbidities and cost-effectiveness.

Study of prescription patterns can help in identifying prevalent practices of the use of medications in real life. Prescription pattern of the antidepressants has been studied in India3,4,5,6. A multicentre study aiming to identify prescription patterns of antidepressants in depression across India in diverse settings found that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) formed 79.2 per cent of all the prescriptions and escitalopram was the most commonly prescribed antidepressant (40%), followed by sertraline (17.6%) and fluoxetine (16.3%)3. Most of the earlier Indian studies examining antidepressant prescription patterns have evaluated the pattern of antidepressant use in unipolar depression only and examined the first prescription provided to the patients. Studies from Europe7, East Asia8,9 and US10 suggest that newer antidepressants, especially SSRIs are the most commonly prescribed antidepressants.

The current study was planned to assess the pattern of antidepressant use across all the psychiatric disorders in five geographically distant tertiary psychiatric care centers of India.

Material & methods

This was a multicentric investigator initiated research study conducted at five tertiary care psychiatric facilities of India at Lucknow (Uttar Pradesh), Chandigarh, Tiruvalla (Kerala), Mumbai (Maharashtra) and Guwahati (Assam). This survey was a part of Research on East Asia Psychotropic Prescriptions (REAP), an International collaborative study involving 10 countries and areas in Asia. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committees of the respective institutions.

Sample selection: In this cross-sectional study, all those patients who were attending OPDs or were admitted in the Psychiatry wards on a fixed day, who were using or had been prescribed antidepressant medications, were approached. Patients giving written informed consent were included in the study. There were no specific exclusion criteria in terms of age, diagnosis and comorbidity. Eligible patients were enrolled consecutively, and their basic socio-demographic and clinical data were collected using a questionnaire designed for the study. The data were collected using a unified research protocol at every collaborating centre that included details of centres, basic socio-demographic variables of patients, clinical details of psychiatric and medical illness as well as prescriptions. Psychiatric diagnoses were established as per International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10)11. Consensus meeting on data collection and uniform data entry was held before survey. Data collection was completed in March 2013.

Statistical analysis: All statistical analysis was performed using SPSSv19.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Parametric data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Prescription patterns were analyzed to determine correlates between types of medication used and patient factors, including socio-demographic and clinical variables. Independent sample Student t tests and one way-ANOVA were used to identify significant differences for continuous variables; chi-square test was used for categorical variables.

Results

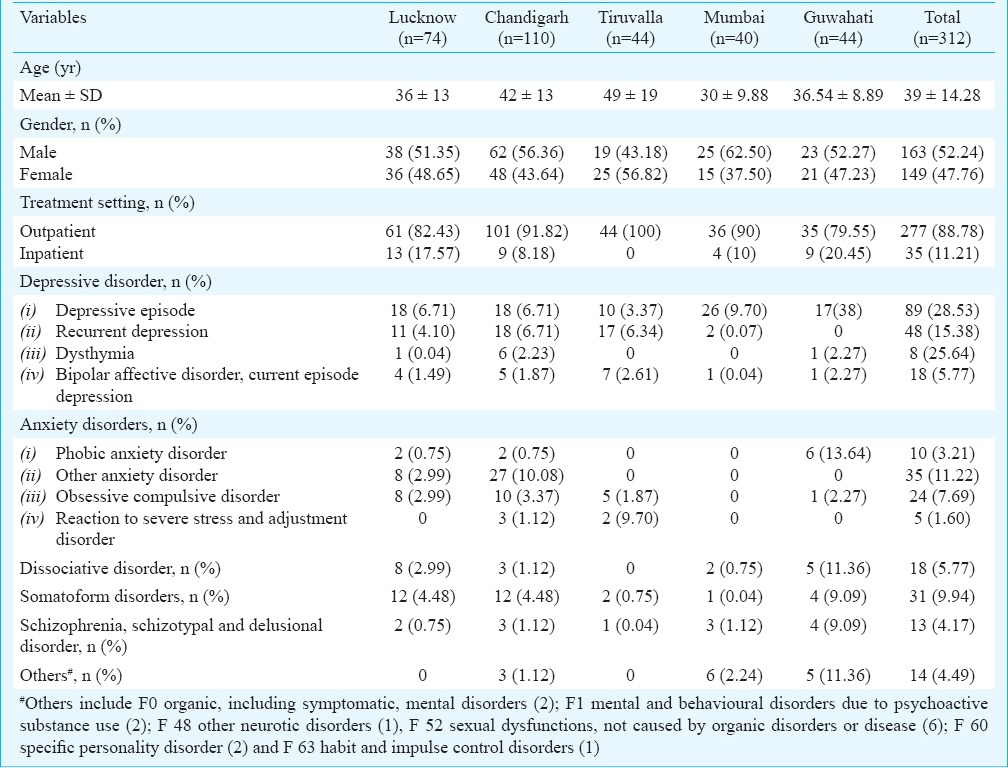

Across the five centres, 312 patients were included (Lucknow-74, Chandigarh-110, Tiruvalla-44, Mumbai-40 and Guwahati-44). The mean age of the patients was 39±14.28 yr and 149 (47.76 %) were females. Of these 312 patients, 35 (11.21%) were inpatients and the remaining were attending outpatient clinics on that day (Table I). This survey focused on gathering data from patients receiving antidepressants due to any reason and any phase of the illness and not just the first prescriptions. Patients with depressive and anxiety disorders receiving antidepressants were 163 (52.2%) and 74 (23.7%), respectively. Other disorders were somatoform disorders, dissociative disorders and psychotic disorders including others which constituted 76 (24.4%) of the prescriptions in this sample.

Table I.

Demographic, clinical and diagnostic details of the patients

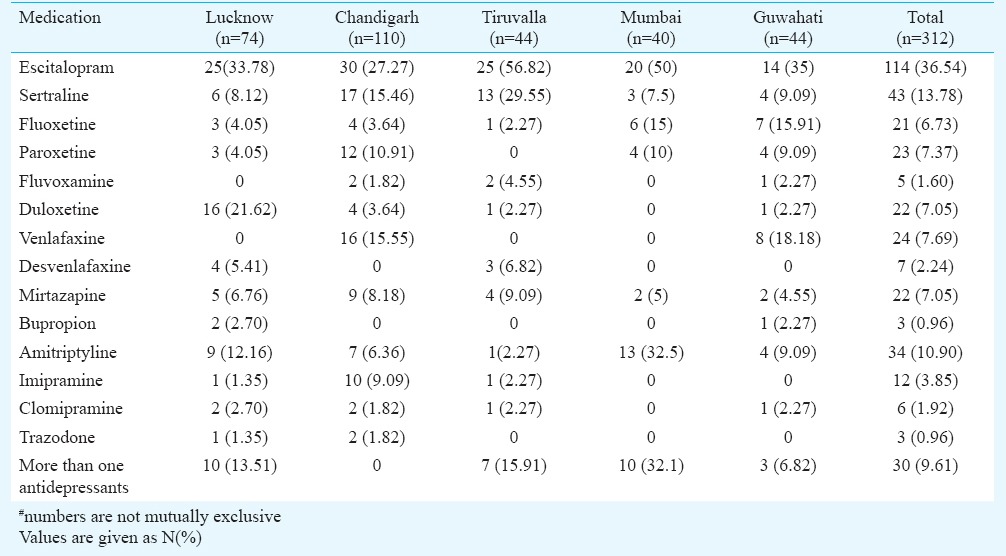

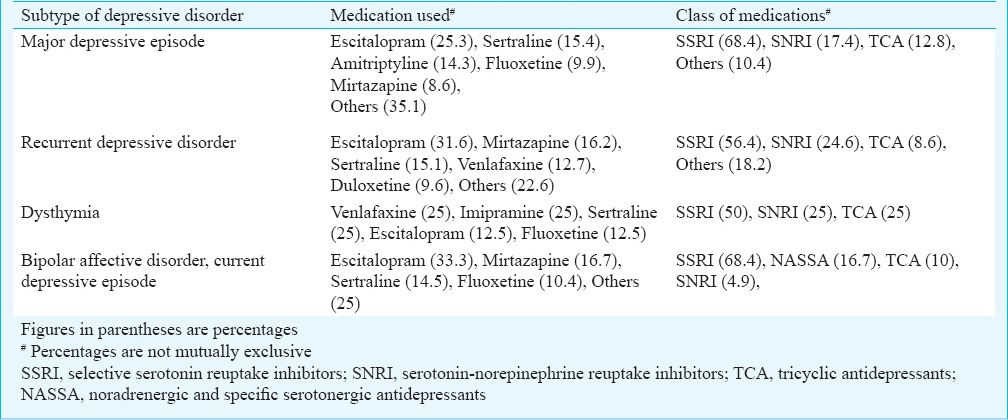

Anti-depressant prescription patterns of the patient are shown in Table II. The most common antidepressant used in depressive disorders was escitalopram followed by sertraline. The most common antidepressant in other anxiety disorders was escitalopram followed by paroxetine. Fluoxetine and escitalopram were the most common antidepressants used in obsessive compulsive disorder. Duloxetine and amitriptyline were most common antidepressants used in somatoform disorders. Escitalopram was also the most used antidepressant in bipolar affective disorder. Amitriptyline was most common antidepressant used in dissociative disorders. Types of antidepressants used in various subtypes of depression are presented in Table III. SSRI was the most common group across all the subtypes constituting around more than half of the prescriptions. Mirtazapine was more commonly used in bipolar affective disorder and current depressive episode patients in comparison to other subtypes of depression. Others medications used included mirtazapine, bupropion and trazodone. One hundred ninety four (62.2%) patients were using SSRIs. Of these, the number of patients receiving escitalopram, sertraline, paroxetine and fluoxetine were 114 (36.54%), 43 (3.78%), 23 (7.37%) and 21 (6.73%), respectively (Table II). Two hundred seventy two (87.18%) patients were using newer antidepressants. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) were the most common older antidepressants used; however, mostly TCAs were used in combination with one newer drug. Thirty three (10.58%) patients were using only older antidepressants. No difference in gender or age was found between patients using new or older types of anti-depressants. Inpatients were significantly more likely to be prescribed TCAs than outpatients (P<0.01). Patients attending public hospitals were more likely to be prescribed TCAs than those attending private hospitals at Tiruvalla, Kerala (23.1 vs 9.1%; P<0.05), while patients in private hospitals were significantly more likely to be prescribed SSRIs (59.7 vs 93.2%; P<0.001).

Table II.

Antidepressant prescription pattern across centers#

Table III.

Antidepressants used (%) in subtypes of depressive disorders

Thirty (9.62%) patients were prescribed more than one antidepressant. SSRIs with TCAs was the most common combination used in half of these cases. SSRIs with mirtazapine or bupropion and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) with mirtazapine were other combinations used. Depressive disorders were the most common diagnosis in the patients using two antidepressants. Other diagnoses were obsessive compulsive disorder and somatoform disorders. All centres except Chandigarh used antidepressants combinations.

Forty seven (15.1%) patients had more than one psychiatric diagnosis. No significant difference in age and sex was found between patients with one psychiatric diagnosis or those with multiple psychiatric diagnoses or additional co-morbidities. Inpatients were more likely to have multiple psychiatric diagnoses than outpatients (25.5 vs 8.7%; P<0.01) while those in a public hospitals were more likely to have multiple psychiatric diagnoses than those in a private hospital (17.5 vs 0%; P<0.001). People with more than one psychiatric diagnosis were more likely to be prescribed sedatives (73.3 vs 53.2%; P<0.05), however, there was no difference in the use of TCAs, SSRIs or SNRIs between patients with one or more than one psychiatric diagnosis.

Seventy (22.44%) patients had one or more physical co-morbidity. Diabetes mellitus (5.78%) was the most common medical illness. No significant differences in medication use were observed in patients with additional physical co-morbidities such as diabetes and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Patients with disturbed sleep were significantly more likely to have been prescribed sedatives (52.3 vs 48.9%; P<0.01) but less likely to have been prescribed SSRIs (57.7 vs 63%; P<0.01). Patients with fatigue were significantly more likely to have been prescribed sedatives than those who did not report fatigue (52.7 vs 49.7%; P<0.001). Poor or increased appetite was associated with use of sedatives (64.6 vs 51.3%; P<0.01) while guilt or self-blame was associated with lower use of antidepressants (83.3 vs 96.8%; P<0.01) and increased use of sedatives (73.3 vs 54.3%; P<0.01).

Average dose of major medications used were for SSRI, escitalopram 11.65 ± 6.4 mg/day (range 5-40), sertraline 83.53± 43.4 mg/day (range 25-200), fluoxetine 33.23 ± 18.3 mg/day (range 10-80) and paroxetine 27.02 ± 11.0 mg/day (range 12.5-50); for TCAs imipramine 78.85 ± 74.2 mg/day (range 25-225) and amitriptyline 41.99 ± 33.7 mg/day (range 10-175). For others, the mean dose for mirtazapine was 20.71± 16.2 mg/day (range 7.5-45) and duloxetine was 53.91± 16.8 mg/day (range 20-80).

About half of the patients (50.96%, n=159) were using hypnotic or sedative medications along with the antidepressants. Clonazepam was the most commonly used hypnotic/sedative medication (37.18%, n=116) followed by lorazepam (8.33%, n=26), alprazolam (3.85%, n=12), zolpidem (3.53%, n=11), etizolam (3.21%, n=10) and chlordiazepoxide (3.21%, n=10). One fifth (19.55%, n=61) were prescribed antipsychotics with antidepressants. Olanzapine (10.26%, n=32) was most commonly prescribed antipsychotic followed by risperidone (2.56%, n=8), trifluperazine (1.92%, n=6), quetiapine (1.60%, n=5), and chlorpromazine (1.60%, n=5). Nineteen (6.1%) patients were using mood stabilizers with lithium carbonate (3.85%, n=12) being most common mood stabilizer prescribed with antidepressants.

Discussion

Studies evaluating the prescription pattern of antidepressants have been conducted at international7-9, primary and specialist care levels12. There is a relative paucity of multicentric Indian studies examining antidepressant prescription patterns. A multicentric Indian study looked into national prescription patterns of antidepressants for patients with diagnoses of major depressive disorder as per Diagnostic and Statistical manual- IV (DSM- IV)3. Our study differed from other previous Indian studies in that it included patients suffering from depression with psychiatric and medical co-morbidities. It included all patients receiving antidepressants for various reasons and not just those suffering from depression and included patients prescribed antidepressants at any phase of treatment and follow up.

Our study suggested that depressive disorders and anxiety disorders were the most common diagnoses where antidepressants were used. This study also confirmed that about half of the patients who were receiving antidepressants had diagnoses other than depression. An earlier international study from East Asia reported that 38.4 per cent of prescriptions of antidepressants were for patients with diagnoses other than depressive disorders8. Several clinical guidelines support the use of antidepressants for a variety of conditions including anxiety disorders13,14 and other conditions15,16. We collected data from tertiary care centres where it was likely that difficult to treat and patients with multiple co-morbidities would cluster. This may be reason for higher numbers of patients with diagnoses other than depression who were receiving antidepressants.

SSRIs were the most commonly prescribed medications among antidepressants in comparison to other groups. Escitalopram was the first choice among SSRIs and was being used in 37.3 per cent cases. This finding was similar to another study from an Indian3 and other national10 and multinational studies6-8. It is also noteworthy that the dosages of the SSRIs and SNRIs used were nearer to their optimal level17. However, other medications, including TCAs, were mostly being used below their recommended dosages.

Clonazepam is the preferred benzodiazepine with antidepressants as evidence from studies has suggested that it has the potential to increase the effects of SSRI and can partially suppress the adverse effects of SSRI18,19. An additional 6.72 per cent of patients were prescribed other sedatives and hypnotics such as zolpidem and etizolam. Patients with more than one psychiatric diagnosis were more likely to be prescribed sedatives than those with a single psychiatric diagnosis. Patients reporting poor sleep, appetite disturbances, guilt/self blame and fatigue were more likely to be prescribed sedatives and hypnotics. Except poor sleep, other symptoms are not indications for using sedatives and hypnotics. Presence of these symptoms simply suggest relatively more severe depression hence use of more medication in this sample. The prescription rate of benzodiazepine remains high in our study but may be less in comparison to other Indian studies evaluating prescription patterns in patients with depressive disorders3,5. Earlier studies have enumerated reasons for benzodiazepine use such as anticipated worsening of anxiety with antidepressants and high co-morbid anxiety in depression. Higher rates of use of benzodiazepines are reported in patients of depression with suicidal intent, anxiety or agitation and it has been found useful in comparison to antidepressants alone18,20,21. However, benzodiazepines should be prescribed with caution. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines suggest that a benzodiazepine may be helpful for up to two weeks early in the treatment particularly in combination with SSRIs and use beyond this time line is discouraged22. These are clearly addictive and many patients may continue to use benzodiazepines for years with unknown benefits and much likely harm. Therefore, this fact needs to be emphasized to the prescribers and attempts to use benzodiazepines for shortest period of time in smallest dose should be made.

Other commonly used psychotropic medications with antidepressants were antipsychotics and about one fifth patient in this study were using this combination. It has been reported that antipsychotic prescriptions have increased with antidepressants in a national prescription pattern study from America10. The reason may be that adjuvant antipsychotics can augment the action of antidepressants. However, this strategy is associated with an increased risk of discontinuation due to adverse events23 and should be used with caution.

Our study included patients with co-morbid physical disorders and, therefore, reflects data from real life prescription practices. Due to the relatively safer side effect profile and decreased risk of drug-drug interactions, SSRIs were the most commonly used medication in patients having co-morbid medical conditions24, although no significant differences were observed in the patterns of medication use between those with co-morbid medical conditions and those without.

It was noted that the choice of antidepressants in this study was as per recommendations of the present treatment guidelines of the psychiatric disorders. However, higher use of benzodiazepines, combined SSRIs and TCAs use are the areas where more awareness of prescribers is needed. Long-term studies with more rigorous methodology and larger sample size may identify reasons for such prescribing practices. Use of appropriate prescribing practices should be encouraged for optimal outcome of patients.

Findings from this study are to be interpreted in the light of the following limitations. Prescription patterns vary greatly according to the clinical setting and clinicians variables7,8. The results of this study are unable to provide sufficient information regarding clinical appropriateness of antidepressants use. This study was cross-sectional in nature, therefore, observations of long term patterns of antidepressant use were not possible. The sample size was small and hence the findings could not be generalized. The study did not include a sufficient number of children, adolescent or elderly to report meaningful data on these subgroups. The study was conducted at tertiary psychiatric care centres at teaching medical institutions; therefore, results may not apply to other settings.

Acknowledgment

Authors thank Shri P.K Sinha for suggestions during statistical analysis and manuscript preparation, and Shri Sanjeev Kumar Singh for assistance in data compilation.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- 1.Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P, editors. Kaplan & Sadock's synospsis of psychiatry. 11th ed. Philadelphia: Wolter Kluver; 2015. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; pp. 3190–205. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson IM. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors versus tricyclic antidepressants: a meta-analysis of efficacy and tolerability. J Affect Disord. 2000;58:19–36. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00092-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grover S, Avasthi A, Kalita K, Dalal PK, Rao GP, Chadda RK, et al. IPS multicentric study: Antidepressant prescription patterns. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55:41–5. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.105503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grover S, Kumar V, Avasthi A, Kulhara P. An audit of first prescription of new patients attending a psychiatry walk-in-clinic in north India. Indian J Pharmacol. 2012;44:319–25. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.96302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trivedi JK, Dhyani M, Sareen H, Yadav VS, Rai SB. Anti-depressant drug prescription pattern for depression at a tertiary health care center of Northern India. Med Pract Rev. 2010;1:16–8. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chakrabarti S, Kulhara P. Patterns of antidepressant prescriptions: I acute phase treatments. Indian J Psychiatry. 2000;42:21–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bauer M, Monz BU, Montejo AL, Quail D, Dantchev N, Demyttenaere K, et al. Prescribing patterns of antidepressants in Europe: Results from the Factors Influencing Depression Endpoints Research (FINDER) study. Eur Psychiatry. 2008;23:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uchida N, Chong MY, Tan CH, Nagai H, Tanaka M, Lee MS, et al. International study on antidepressant prescription pattern at 20 teaching hospitals and major psychiatric institutions in East Asia: Analysis of 1898 cases from China, Japan, Korea, Singapore and Taiwan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;61:522–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2007.01702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sim K, Lee NB, Chua HC, Mahendran R, Fujii S, Yang S, et al. Newer antidepressant drug use in East Asian psychiatric treatment settings: REAP (Research on East Asia Psychotropic Prescriptions) Study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;63:431–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02780.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olfson M, Marcus SC. National patterns in antidepressant medication treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:848–56. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geneva: WHO; 1992. World Health Organization (WHO). The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kjosavik SR, Hunskaar S, Aarsland D, Ruths S. Initial prescription of antipsychotics and antidepressants in general practice and specialist care in Norway. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;123:459–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ballenger JC, Davidson JR, Lecrubier Y, Nutt DJ, Bobes J, Beidel DC, et al. Consensus statement on social anxiety disorder from the International Consensus Group on Depression and Anxiety. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:54–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Psychiatric Association Work Group on Panic Disorder. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldenberg DL, Burckhardt C, Crofford L. Management of fibromyalgia syndrome. JAMA. 2004;292:2388–95. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.19.2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Altshuler LL, Cohen LS, Moline ML, Kahn DA, Carpenter D, Docherty JP. Expert Consensus Panel for Depression in Women. The Expert Consensus Guideline Series: treatment of depression in women. Postgrad Med. 2001:1–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor D, Paton C, Kapoor S. The maudsley prescribing guidelines in psychiatry. 11th ed. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell Publications; 2012. p. 218. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morishita S. Clonazepam as a therapeutic adjunct to improve the management of depression. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2009;24:191–8. doi: 10.1002/hup.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nardi AE, Giampaolo P. Clonazepam in the treatment of psychiatric disorders. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;21:131–42. doi: 10.1097/01.yic.0000194379.65460.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morishita S, Arita S. Possible predictors of response to clonazepam augmentation therapy in patients with protracted depression. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2007;22:27–31. doi: 10.1002/hup.818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furukawa TA, Streiner DL, Young LT. Antidepressant and benzodiazepine for major depression. J Affect Disord. 2001;65:173–7. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00254-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder (with or without agoraphobia) in adults. Clinical Guidelines CG113. 2011. [accessed on September 9, 2013]. Available from: www.nice.org.uk . [PubMed]

- 23.Nelson JC, Papakostas GI. Atypical antipsychotic augmentation in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:980–91. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09030312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kurzthaler I, Hotter A, Miller C, Kemmler G, Halder W, Rhomberg HP, et al. Risk profile of SSRIs in elderly depressive patients with co-morbid physical illness. Psychopharmacology. 2001;34:114–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-14281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]