Abstract

Background

The enhanced sensitivity of cardiac troponin T (cTnT) assays calls for its use as a prognostic marker in chronic heart failure, as an accurate and early marker of myocyte damage, and as a sensitive indicator of acute episodes in chronic disease. To facilitate these applications and inform required benchmarks, we estimated the variability in cTnT measurements, the sources of this variability, and the stability of cTnT using samples stored at −70 °C.

Methods and Results

Stored samples from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study (ARIC) study (1996–1998) and ARIC Carotid MRI study participants (2005–06) were assayed in 2009–10 to examine variability in cTnT attributable to laboratory (replicates after freeze thaw, n=29), processing (blind replicates from same blood draw, n = 87), short- (n = 40) and long-term biological variation (repeat visit, n = 38), and degradation in frozen storage (n = 10,870). The Elecsys Troponin T (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) was used to assay cTnT on an automated Cobas e411 analyzer. The lower limit of detection was 3 ng/L. Approximately 1/4th to 1/3rd of the participants had values below the detection limit. The paired correlation for all other comparisons exceeded 0.93 (except for samples drawn 8 years apart = 0.36). The coefficients of variation for individual sources of variation in cTnT were as follows: laboratory 2.1% in those with heart failure (HF) and 11.2% in those without HF; processing 18.3%; biological at six weeks 16.6%, and at eight years 48.4%. The reference change value at 6 weeks was 68.5% and would require 4 samples to determine homeostatic set point within ± 25%. Only modest degradation was detected in stored frozen samples for an average of 8 years.

Conclusions

cTnT is detectable in approximately 70% of community-dwelling men and women aged 53 to 75 years. The laboratory reliability was high: the reliability coefficient (r) was 0.99 in those with heart failure and 0.94 in those without heart failure. The intra-individual (biologic) variability was low on repeat testing after 6 weeks (r=0.94), and increased for measurements taken 8 years apart (R=0.36). Troponin T is stable in storage at −70° C and the variability in cTnT values attributable to one freeze-thaw cycle is of small magnitude.

Keywords: highly sensitive Troponin T, hsTnT, cTnT, variability, measurement error, laboratory variability, intra-individual variation

Introduction

Cardiac troponins are markers of myocardial injury commonly used in the diagnosis of acute coronary events [1–4]. Increased concentrations of circulating troponins are also detectable in patients with both acute decompensated and chronic heart failure (HF) and have been associated with poor patient outcomes [5–12]. Troponin concentrations are generally lower in chronic HF patients than those seen in acute coronary syndromes [13], and therefore necessitate sensitive troponin assays. For example, the highly sensitivity cardiac troponin T (cTnT) assay can detect troponin T concentrations more than 10-fold lower than with traditional assays [14]

There is limited information on the variability of cTnT in individuals not examined in an acute care context, although a 1999 report from the National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry Standards of Laboratory Practice emphasized a need for such studies [15]. Such information is important to determine cutoffs to suggest an acute event in individuals with chronic troponin T elevation. The variability of cTnT was recently reported to be higher than that of the commonly used Troponin I [16].

We examined the variability of cTnT in Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) participants and quantified the components of variability attributed to laboratory, processing, and biological variation. We also estimated the impact of specimen storage at −70 degrees Celsius over three years on levels of cTnT.

Methods

Study Sample

The ARIC Study cohort of middle aged African American and Caucasian males and females was enrolled in 1987–89, sampled from four US communities. The baseline examination (1987–89) was followed by three triennial field center visits. Subsequently, novel cellular, metabolic and genomic correlates of carotid atherosclerosis and early pathologic changes in the carotid artery walls were measured in 2,066 cohort members by the ARIC Carotid MRI Study (2005–06). The present study assayed stored samples from the visit 4 (1996–98) to study stability of cTnT over three years of sample collection. To study the components of variability, stored samples from Carotid MRI study were used. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the four participating centers.

Blood Sampling and Processing

Participants were requested to report after an overnight fast. Venipuncture and specimen processing were performed by centrally trained technicians, using standard protocols at the four field centers. The samples from visit 4 were stored at the field center in a sytrofoam boxes in freezer at −70 ° C, and were shipped every Monday to the central lab by overnight courier. The samples from Car MRI study were shipped on the day of blood draw in insulated styrofoam containers with temperature-stabilizing packages (approximate specimen temperature 10–15 °C) by overnight courier to the ARIC central laboratory [17], and stored at −70 ° C until assayed for this study. The stored samples were assayed in 2009–10.

Biomarker Assays

Plasma samples were stored centrally at –70°C and used for measurement of the biomarkers. cTnT levels were measured with a novel pre-commercial highly sensitive assay, Elecsys Troponin T (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN), on an automated Cobas e411 analyzer with a lower limit of detection of 3 ng/L. The 99th percentile value for the cTnT measured by the new assay in a healthy subpopulation is 14 ng/L (Roche Diagnostics, data on file). The between-assay coefficients of variation were 2.6% and 6.9% for control materials with mean cTnT concentrations of 238 ng/L and 29 ng/L, respectively.

Study Design

A total of five sub-studies (I to V) were conducted – four of them to estimate the components of variability i.e., laboratory, processing, short term biological and long term biological, and the fifth to estimate degradation over 3 years. In sub-study I examining laboratory variability, 30 samples (15 each from individuals with and without HF) from the ARIC Carotid MRI study were split into 2 aliquots, and values obtained from the paired assays were compared and measure of variation estimated. One participant without HF had cTnT below limit of detection (LOD) in split assay; thus information from 14 participants was available for estimation. Measurement variation estimated from these data cannot be attributed to variation in blood drawing, local processing, shipment procedures, laboratory handling and analysis, or within-subject variation over time. A schematic diagram showing various components of variability in the measurement of an assay is shown in supplementary figure 1.

In sub-study II involving 119 Carotid MRI study participants, each field center drew duplicate blood tubes using a single venipuncture during the same visit but were processed (shipping and other details) separately. These duplicate samples were sent to the central laboratory under a blinded quality control (QC) ID that was not distinguishable from how other IDs were labeled and then stored. After the laboratory had analyzed the paired samples the results were compared to estimate the processing variability (i.e., variability in blood processing, shipping, and laboratory handling and analysis) for samples above LOD in replicate samples (n = 87).

In sub-study III involving 60 Carotid MRI study participants, each field center was asked to recruit 15 volunteers to repeat the entire clinic visit within 4–8 weeks of their original visit. Volunteers generally reflected the age, sex, and racial composition of the overall study [18]. Again, duplicate samples were submitted to the central laboratory and stored under a blinded QC ID. Results from the paired samples were compared to give an estimate of short term biologic variability when assays were above LOD at both times (n = 40). It is to be noted that in this and all similar studies paired samples from participants over time will also include variability due to laboratory and processing error too.

In sub-study IV with 161 participants, samples from Carotid MRI study visit (sub-study I through III) and corresponding assays from samples stored during visit 4 (about 8 years before) were used and measures of long term biological variability were assessed after excluding those with CHD, HF, or stroke during the Carotid MRI visit.

In sub-study V, stored samples from all the participants who participated in the ARIC cohort field center visit 4 (n = 10,870) and had cTnT above LOD (n=7,677) were used. There were differences in storage period since collection was spread over an average 3 years, enabling an estimation of degradation during frozen storage.

Covariates

Smoking status, race, and gender, were self reported. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula [19]. Prevalent coronary heart disease (CHD) was defined as either self-reported history of CHD at the baseline visit or an adjudicated CHD event before the fourth exam visit (for the visit 4 analyses) or 12/31/2004, the last date of adjudication (for Carotid MRI study visit). Participants with hospitalizations listing the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) discharge code = 428 in any position were classified with prevalent heart failure.

Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics are presented for participants in each of the sub-studies (I through V) and participants of ARIC Carotid MRI study. By treating paired measurements as a random effect in a linear mixed effects model, we partitioned the total variance () into a between-pair (or between-person, ) and within-pair component of variance. The within-pair component of variance derived from within-visit reliability sub-study II, in which duplicate samples were obtained from participants on the same day, corresponds to an estimate of variation due to blood collection, processing and laboratory analysis (). In contrast, the within-pair component of variance derived from between-visit reliability sub-study III and sub-study IV, in which duplicate samples were obtained from participants at two separate visits, corresponds to an estimate of the within-person (biologic) variation over time plus method variation (). The within-pair variance derived from the split-samples after one freeze-thaw cycle (sub-study I) corresponds to the laboratory variability plus analyte stability. The proportion of the total variance attributable to between-person variability, or the reliability coefficient () can be interpreted as the correlation between paired measurements. The following benchmarks were used for characterization of the adequacy of reliability [20]: slight reliability, 0–0.2; fair reliability, 0.21–0.4; moderate reliability, 0.41–0.6; substantial reliability, 0.61–0.8; almost perfect reliability, 0.81–1.0. Based on our sample sizes of 87 and 40 for the two sub-studies, the 95% confidence interval assuming a moderate reliability of 0.60 will have lower limits of 0.45 and 0.38, respectively.

Coefficient of variation (CV) was derived as the standard deviation of the within-pair differences divided by the mean of the paired observations multiplied by 100. CV values greater than 10% for laboratory or processing variability were considered as a cause for concern.

Reference change values (RCV) were defined as that difference between two consecutive test results in an individual that is statistically significant in a given proportion of all similar persons [21]. For estimating RCV, those below limit of detection were not included. Reference change values (RCV) were calculated as , where Z is the number of standard deviates required for a stated probability under the normal curve. The number of specimens required to produce a precise homeostatic set point estimate is given as: , where D is the desired percentage closeness to the homeostatic set point [22]. Bland-Altman plots (sub-study III and IV) were used to assess the degree of disagreement (including systematic differences) and identify outliers and trends between the two repeat measures at 4–8 weeks apart [23].

Although our study design precluded performing cTnT assays at pre-specified time intervals to evaluate sample degradation at −70° C storage over time, the timing of the cohort examination visits in ARIC was assigned at random, resulting in a uniform distribution of participants by study month. Degradation in stored frozen storage was therefore examined by regressing analyte concentration on time since specimen collection. A roughly flat slope would suggest little degradation, whereas a negative slope would provide evidence of sample decay.

Analysis were done using SAS software version 9.2, Cary, NC.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of study participants for sub-studies I through V are shown in table 1. Median age at sample collection was 63 years at visit 4 (long term variability and degradation study) and over 70 years for sub-studies I through III using only Car-MRI visit data. The average prevalence of co-morbidities in sub-studies during visit 4 and Car-MRI visit was CHD (6 to 8% vs. 15 to 18%), and heart failure (2.4 to 2.5% vs. 5.0 to 6.0%) respectively.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of ARIC participants who contributed to the within-visit and between-visit replicate samples.*

| Sub-study I | Sub-study II | Sub-study III | Sub-study IV | Sub-study V | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lab variability, heart failure |

Lab variability , no heart failure |

Processing variability |

Six-week intra-individual variability |

Eight-year intra-individual variability† |

Long-term degradation |

|

| N | 15 | 15 | 119 | 60 | 161 | 10,870 |

| Study years | 2005–2006 | 2005–2006 | 2005–2006 | 2005–2006 | 1996–2006 | 1996–1998 |

| Median age (range) | 77 (69, 81) | 73 (69, 81) | 71 (60, 82) | 71 (61, 82) | 63 (53, 75) | 63 (53, 75) |

| Male, % | 53.3 | 46.7 | 47.9 | 57.4 | 50.3 | 43.1 |

| African American, % | 26.7 | 33.3 | 21.0 | 29.5 | 23.0 | 21.3 |

| Median BMI (range) | 31.0 (23.7, 43.3) | 27.6 (21.8, 45.5) | 28.6 (19.7, 57.1) | 26.5 (19.8, 46.2) | 27.3 (16.8, 56.4) | 27.9 (13.5, 59.2) |

| Median eGFR (range) | 59.4 (35.3, 86.9) | 80.6 (65.9, 143.1) | 78.2 (29.6, 189.5) | 82.0 (29.6, 228.8) | 104.4 (57.4, 239.6) | 106.0 (3.2, 875.5) |

| Prevalent CHD, % | 66.7 | 0 | 14.4 | 18.0 | 6.3 | 8.8 |

| Prevalent heart failure, % | 100 | 0 | 5.9 | 4.9 | 2.5 | 2.4 |

| Current smokers, % | 7.1 | 0 | 6.0 | 3.3 | 11.8 | 14.8 |

Presented as percentages for dichotomous variables and medians (range) for continuous variables.

Calculated during the 4th ARIC clinic visit. ARIC, Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study; BMI, body mass index; CHD, coronary heart disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; IMT, intima medial thickness

Estimates of the 95th and 99th percentiles of cTnT in the ARIC visit 4 cohort (n=10,870) were 18 ng/L and 40 ng/L with inter-quartile range of 3 to 8 ng/L. Also, 31.6% of visit 4 samples and 26.9 % of Car MRI samples were below detection limits.

cTnT measures after a single freeze thaw cycle (sub-study I), different processing after collection from a single venous stick (processing reliability, sub-study II), repeat visit within 4–8 weeks (sub-study III), demonstrated very high reliability with r>0.93 (table 2). However, reliability after 8 years duration (sub-study IV) was low, r = 0.36 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sample means, standard deviations, reliability coefficients (R), and coefficients of variation for cTnT replicate samples, the ARIC (1996–1998) and ARIC Carotid MRI (2005–2006) Studies

| Sub-study (number) | N QC Pairs | Mean (ng/L) | SD* | R† | CV‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory reliability (I) | |||||

| With heart failure | 15 | 24.5 | 0.51 | 0.99 | 2.1 |

| Without heart failure | 14 | 8.6 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 11.2 |

| Processing reliability (II) | 87 | 9.4 | 1.7 | 0.93 | 18.3 |

| Intra-individual variability (III and IV) | |||||

| Six weeks | 40 | 9.7 | 1.6 | 0.94 | 16.6 |

| Eight years | 38 | 9.0 | 4.3 | 0.36 | 48.4 |

Standard deviation = square root (within-subject variance);

Estimate of correlation between repeated measurements;

Lab SD expressed as a percent of the mean of QC pairs; CV, coefficient of variation; cTnT, cardiac Troponin T; N, number; QC, quality control; SD, standard deviation; (1) for estimation of analyte freeze-thaw variability; (3) for estimation of processing variability; (3) for estimation of short- and long-term intraindividual variability; Observations with values < LOD were removed from all analyses.

After removing observations below the LOD, the mean of cTnT were 24.5 ng/L in those with HF vs. 8.6 ng/L in those without. The CVs in paired replicate after a freeze-thaw cycle in those with and without HF in were 2.1% and 11.2%, respectively. There was high processing variability with CV of 18.3% (though reliability was high, r = 0.93).

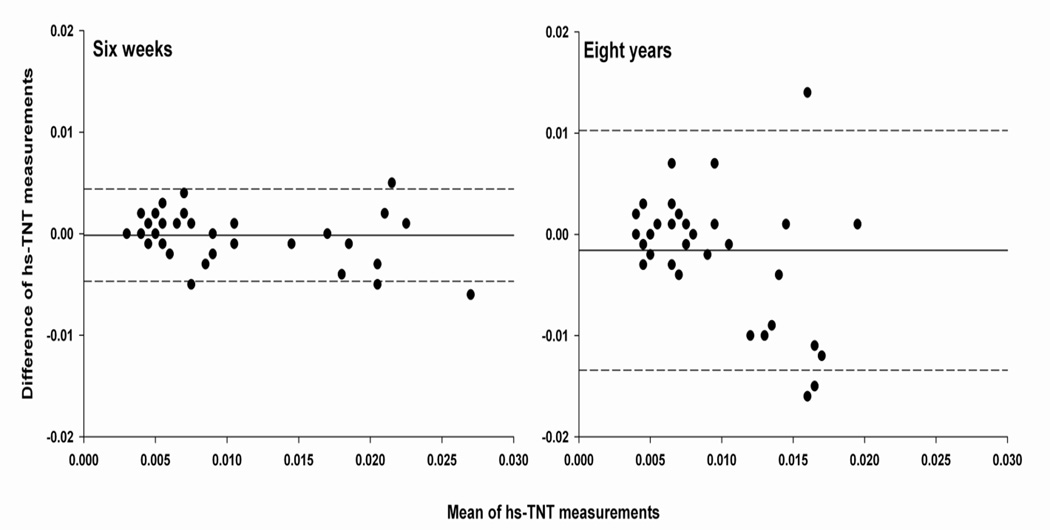

The variability between repeated visits 4–8 weeks apart was not large (CV = 16.6%). The mean of the differences between these repeat visits was 0 ng/L with a range from −5 to 6 ng/L and inter-quartile range (IQR) from - 1 ng/L to 1 ng/L. Bland-Altman plots (figure 1) did not support a relationship between differences in cTnT measures and the mean cTnT level. The RCV, calculated using repeat visits spaced approximately six weeks apart, was 68.5%, suggesting that cTnT changes over a six week interval must be greater than 67% of the baseline value to be considered biologically significant (table 3). Correspondingly, for a six-week interval, 23 and 4 samples would be needed to identify an individuals’ cTnT (i.e. homeostatic set point) level within ±10% and ±25% with 95% confidence, respectively (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Bland-Altman plot showing bias against the mean of cTnT measurements obtained six weeks and eight years apart with 95% levels of agreement (broken lines). The differences and means are expressed in microgram/L.

Table 3.

Reference change values and number of samples needed to determine homeostatic set point for cTnT over 6 week measurement intervals. The ARIC Carotid MRI Study, 2005–2006

| RCV, % | 68.5 |

| No. samples | |

| (±10; CI 95%) | 23 |

| (±25; CI 95%) | 4 |

| (±50; CI 95%) | 1 |

CI, confidence interval; cTnT, high sensitivity troponin T; RCV, reference change value

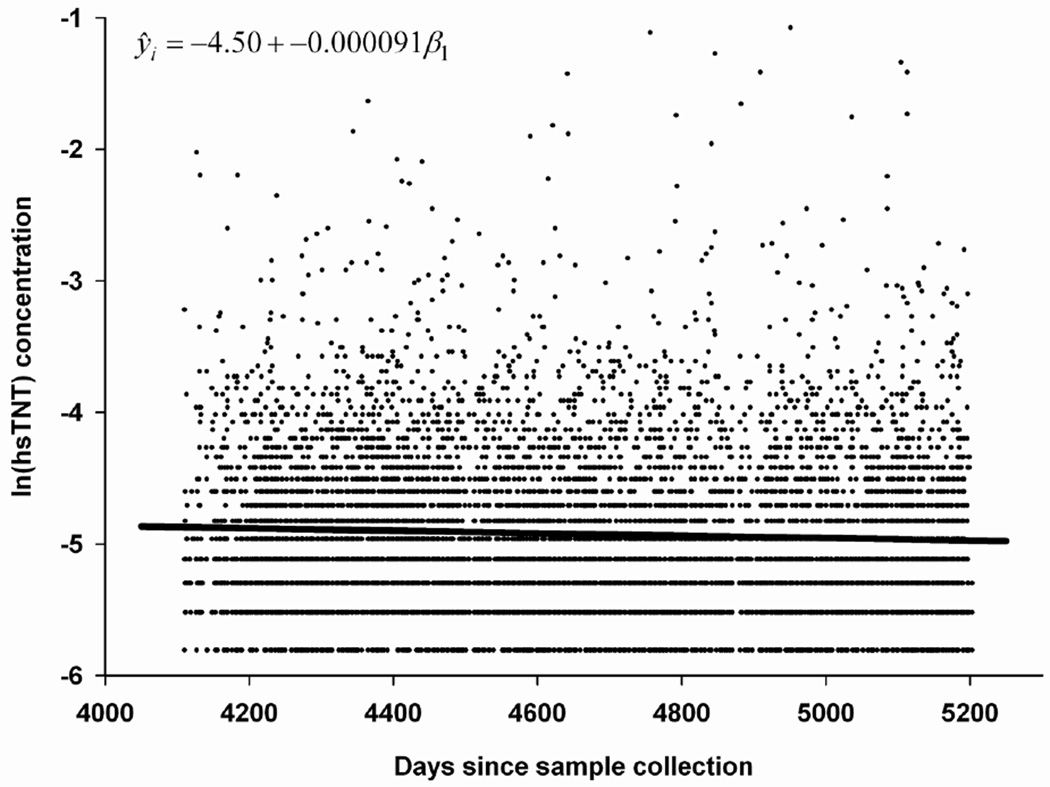

Examination of long term (i.e. 8-year) biological variability suggests a SD of 4.3 at a mean value of 9 ng/L (CV = 48.4%). The mean of differences between these visits 8 years apart was 1.6 ng/L with range from −16 to 14 ng/L and IQR from - 4 ng/L to 1 ng/L. There was evidence of late degradation when stored sample collected over a period of 36 months was regressed on time since collection. A mean degradation of 0.36 (95% CI: 0.19 to 0.53) ng/L in cTnT per year was seen (figure 2). This degradation was not evident when we examined proportions of samples below detection limit collected during a quarter year with varying duration of storage since collection during visit 4 to measurement in 2009–10 (supplementary figure 2).

Figure 2.

Influence of time since collection on cTnT concentration in n=7,677 samples collected over 1,093 days in 1996–98 and stored at −70 °C till measurement in 2009–2010 i.e. freezer time varying from 11 to 14 years.

Discussion

This study comprehensively reports on various components of variability in the measurement of high sensitivity Troponin T and on the stability of troponin T in samples stored at −70 °C. The laboratory reliability of the cTnT assay was high: the reliability coefficient (R) was 0.99 in those with heart failure and 0.94 in those without heart failure. The intra-individual (biologic) variability was similarly high after 6 weeks (R=0.94), but was lower t after 8 years (R=0.36). After excluding those with events (CHD, HF, and stroke) between the repeat visits, R changed to 0.28 and CV was 54.9% (as compared to 48.4% in the complete sample).

In another study using the pre-commercial electrochemiluminescense assay (ECLIA; Elecsys 2010 analyzer, Roche Diagnositics, Germany) the limit of detection was 1 ng/L [14]. A significant correlation was reported between highly sensitive cTnT assay and traditional cTnT assay in those with detectable limit (r=0.84). The intra-assay coefficient of variation was 5% at 10 ng/L and 1% at 100 ng/L [14].

In a recent study examining components of variability in 20 healthy and young volunteers (age range 25–56 years), very short term (0–4 hrs) and short term (0–8 weeks) intra-individual CV were 48% and 85%, respectively [16]. The CV at short term (85%) was higher than that seen in the study reported here (16.6%) – possibly a function of lower mean value of cTnT in a study of healthy young volunteers. In our study there were no appreciable changes in the intra-individual CV (18.5%) after excluding those without CHD or HF or AF.

We are not aware of published studies of the stability of cTnT in stored specimens. Using an indirect approach this study indicates that there is little late phase degradation, however, degradation in the early period of storage could not be ruled out. There was no indication of an increase in proportion of the population below the lower limit of detection with longer freezer storage time (Supplementary figure 2), although the study power for detecting such a change is limited.

It has been reported that the use of a sensitive assay for troponin I improves the early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and aids in risk stratification, regardless of the time of chest-pain onset [27] whereas cTnT did not have higher diagnostic accuracy for AMI [24]. In general, the use of high sensitivity troponin assays improves the information at the lower tail of distribution of cardiac troponin levels, which is usually left-censored and assumed to be either, zero or set at the lower limit of detection. As shown by several studies [5–12] such lower range of values when detectable helps in prognostication .Whether a change in such low range can help in early detection and prevention of myocardial injury such as in drug induced cardiomyopathy or ischemia not amounting to infarction requires additional study. Given the favorable measurement properties of cTnT reported here and elsewhere [14] the ability to detect very low levels of plasma cTnT should allow for a wider range of applications in the clinical context and in research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study is carried out as a collaborative study supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute contracts N01-HC-55015, N01-HC-55016, N01-HC-55018, N01-HC-55019, N01-HC-55020, N01-HC-55021, and N01-HC-55022. The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions. Roche Diagnostics provided reagents and the loan of an instrument to conduct the high sensitivity assays of cTnT.

Abbreviations in the order of their use

- ARIC study

Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study

- HF

Heart Failure

- cTnT

cardiac Troponin T

- Car MRI study

Carotid Magnetic Resonance Imaging study

- CHD

Coronary Heart Disease

- CV

Coefficient of Variation

- RCV

Reference Change Value

- IQR

Inter Quartile Range

References

- 1.Antman EM, et al. Cardiac-specific troponin I levels to predict the risk of mortality in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(18):1342–1349. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610313351802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apple FS, et al. Future biomarkers for detection of ischemia and risk stratification in acute coronary syndrome. Clin Chem. 2005;51(5):810–824. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.046292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donnelly R, Millar-Craig MW. Cardiac troponins: IT upgrade for the heart. Lancet. 1998;351(9102):537–539. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)78549-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindahl B, et al. Markers of myocardial damage and inflammation in relation to long-term mortality in unstable coronary artery disease. FRISC Study Group. Fragmin during Instability in Coronary Artery Disease. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(16):1139–1147. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200010193431602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Del Carlo CH, et al. Serial measure of cardiac troponin T levels for prediction of clinical events in decompensated heart failure. J Card Fail. 2004;10(1):43–48. doi: 10.1016/s1071-9164(03)00594-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horwich TB, et al. Cardiac troponin I is associated with impaired hemodynamics, progressive left ventricular dysfunction, and increased mortality rates in advanced heart failure. Circulation. 2003;108(7):833–838. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000084543.79097.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishii J, et al. Prognostic value of combination of cardiac troponin T and B-type natriuretic peptide after initiation of treatment in patients with chronic heart failure. Clin Chem. 2003;49(12):2020–2026. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.021311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishii J, et al. Risk stratification using a combination of cardiac troponin T and brain natriuretic peptide in patients hospitalized for worsening chronic heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89(6):691–695. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)02341-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sato Y, et al. Serum cardiac troponin T and plasma brain natriuretic peptide in patients with cardiac decompensation. Heart. 2002;88(6):647–648. doi: 10.1136/heart.88.6.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sato Y, et al. Persistently increased serum concentrations of cardiac troponin t in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy are predictive of adverse outcomes. Circulation. 2001;103(3):369–374. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Setsuta K, et al. Use of cytosolic and myofibril markers in the detection of ongoing myocardial damage in patients with chronic heart failure. Am J Med. 2002;113(9):717–722. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01394-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Setsuta K, et al. Clinical significance of elevated levels of cardiac troponin T in patients with chronic heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84(5):608–611. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00391-4. A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aviles RJ, et al. Troponin T levels in patients with acute coronary syndromes, with or without renal dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(26):2047–2052. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Latini R, et al. Prognostic value of very low plasma concentrations of troponin T in patients with stable chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2007;116(11):1242–1249. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.655076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu AH, et al. National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry Standards of Laboratory Practice: recommendations for the use of cardiac markers in coronary artery diseases. Clin Chem. 1999;45(7):1104–1121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vasile VC, et al. Biological and Analytical Variability of a Novel High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin T Assay. Clin Chem. 2010 doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.140616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.ARIC Carotid MRI Study Investigators. Manual 2: Field Center Procedures: Biospecimen Collection and Processing. ARIC Carotid MRI Study manuals. 2006 [cited 2010 July 14th] Available from: http://www.cscc.unc.edu/carmri.

- 18.Catellier DJ, et al. Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Carotid MRI flow cytometry study of monocyte and platelet markers: intraindividual variability and reliability. Clin Chem. 2008;54(8):1363–1371. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.102202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levey AS, et al. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(6):461–470. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fleiss J. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. 2nd. New York: John Wiley; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harris EK, Yasaka T. On the calculation of a "reference change" for comparing two consecutive measurements. Clin Chem. 1983;29(1):25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fraser CG, Harris EK. Generation and application of data on biological variation in clinical chemistry. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 1989;27(5):409–437. doi: 10.3109/10408368909106595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1(8476):307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keller T, et al. Sensitive troponin I assay in early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(9):868–877. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0903515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.