Abstract

Purpose

The addition of bisphosphonates to adjuvant therapy improves survival in postmenopausal breast cancer (BC) patients. We report a meta-analysis of four randomised trials of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (CT) +/− zoledronic acid (ZA) in stage II/III BC to investigate the potential for enhancing the pathological response.

Methods

Individual patient data from four prospective randomised clinical trials reporting the effect of the addition of ZA on the pathological response after neoadjuvant CT were pooled. Primary outcomes were pathological complete response in the breast (pCRb) and in the breast and lymph nodes (pCR). Trial-level and individual patient data meta-analyses were done. Predefined subgroup-analyses were performed for postmenopausal women and patients with triple-negative BC.

Results

pCRb and pCR data were available in 735 and 552 patients respectively. In the total study population ZA addition to neoadjuvant CT did not increase pCRb or pCR rates. However, in postmenopausal patients, the addition of ZA resulted in a significant, near doubling of the pCRb rate (10.8% for CT only versus 17.7% with CT+ZA; odds ratio [OR] 2.14, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.01–4.55) and a non-significant benefit of the pCR rate (7.8% for CT only versus 14.6% with CT+ZA; OR 2.62, 95% CI 0.90–7.62). In patients with triple-negative BC a trend was observed favouring CT+ZA.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis shows no impact from the addition of ZA to neoadjuvant CT on pCR. However, as has been seen in the adjuvant setting, the addition of ZA to neoadjuvant CT may augment the effects of CT in postmenopausal patients with BC.

Keywords: Neoadjuvant, Chemotherapy, Breast cancer, Zoledronic acid, Bisphosphonates, Pathological complete response

1. Introduction

The anti-tumour effect of bisphosphonates is still an issue of debate. Recently, the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) meta-analysis in 17,791 patients demonstrated that adjuvant bisphosphonates reduce bone metastases and improve survival in postmenopausal women with early breast cancer (BC) [1].

Several studies have also suggested that the addition of zoledronic acid (ZA) to chemotherapy (CT) in the neoadjuvant setting may be beneficial and result in increased rates of pathological complete response (pCR) [2–4]. However, the body of evidence for this is limited due to the low number of patients and relatively discordant findings [2–5]. In the neoadjuvant subset of the AZURE study, consisting of 205 patients with cT3 or cT4 disease or biopsy-proven lymph node involvement, the pCR rate nearly doubled in the cohort of patients who received ZA (4 mg q3–4 weeks, six doses) as an adjunct to neoadjuvant CT. Aft et al. reported that ZA administration resulted in a significant decrease in detectable disseminated tumour cells in patients with clinical stage II/III BC treated with four cycles of neoadjuvant epirubicin plus docetaxel, in comparison to patients who were treated with CT only [3]. In contrast, the two comparative phase III trials which were prospectively designed to evaluate pCR rates following neoadjuvant CT with or without ZA 4 mg intravenously at the beginning of each cycle failed to show a beneficial effect in their stage II/III early BC population [4,5]. However, in both of these studies a numerical benefit was observed in postmenopausal women specifically, seemingly concordant with the data from the neoadjuvant AZURE subgroup analysis and the adjuvant meta-analysis.

Together, study results support the hypothesis that ZA may have an anti-tumour effect and that synergism may occur with CT[6]. We report a meta-analysis of individual patients data from all randomised studies that have compared the use of ZA (4 mg, 4–6 doses, q3–4 weeks) combined with neoadjuvant CT versus no bisphosphonate in patients with early BC.

2. Methods

2.1. Included studies

Patients from four prospective randomised studies were included in this meta-analysis. The NEOZOTAC trial analysed 246 patients which received six three-weekly cycles of TAC CT (docetaxel, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide with pegylated G-CSF within 24 h) with or without ZA (4 mg intravenous [i.v.]). The JONIE1 trial randomised 180 patients to receive neoadjuvant CT (four three-weekly cycles FEC [5-fluorouracil, epirubicin, cyclophosphamide] followed by 12 weekly cycles paclitaxel) with or without seven infusions of ZA 4 mg. In the neoadjuvant subset of the AZURE study, 205 patients received neoadjuvant CT following local guidelines, with or without ZA 4 mg, every 3–4 weeks, for six doses. In the study by Aft et al. 119 patients (one patient withdrew consent) received four cycles of intravenous neoadjuvant epirubicin plus docetaxel every 3 weeks, with granulocyte-stimulating factor support, with or without ZA (4 mg i.v.). Time of zoledronate infusion was after CT infusion in all of the studies. As the timing of infusion was not specified no analysis was done regarding the exact timing of infusion.

2.2. Variables collected from each study

Participating study groups were asked to provide patient data on the following variables: oestrogen receptor (ER)-status, progesterone receptor-status, cT-status, cN-status, menopausal status, age, pathological complete response in the breast (pCRb)-status, pathological complete response in the breast and lymph nodes (pCR)-status and allocated treatment. pCRb was defined as absence of invasive tumour cells in the breast.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics in treatment arms were compared with the Pearsons’s chi-square test, or if applicable Fisher’s exact test, in case of categorical variables or the Manne–Whitney-U test in case of continuous variables. Homogeneity of the treatment effect among studies was tested using the Q statistic and by calculating the I2-value. Data were analysed on a trial-level as well as on individual patient level. Due to the homogeneity of study effect sizes fixed-effects models were used. For the trial-level approach, odds ratios (OR) of each separate study were calculated, correcting for the classical predictors ER-status and cT-status (cN-status was not completely collected in some studies). Pooling of ORs was performed using inverse variance weighting.

As for individual patient data analyses multivariate logistic regression correcting for ER-status and cT-status was used to calculate the OR. Subgroup analyses based on menopausal status (pre/perimenopausal versus postmenopausal as defined per trial and by age) and hormone-receptor status (triple-negative tumours which are more likely to achieve pCR versus all other tumours with known receptor status) were pre-specified.[7] The null hypothesis that the effect sizes of the intervention (ZA) did not differ significantly between subgroups was tested by adding an interaction between subgroup characteristics and treatment (neoadjuvant CT+ZA versus neoadjuvant CT alone) in the logistic regression analyses. Statistical analyses were done using SPSS (version 20.0 for Windows, IBM SPSS Statistics) and R (package ‘meta’, version 2.15.0, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

3. Results

3.1. Patients

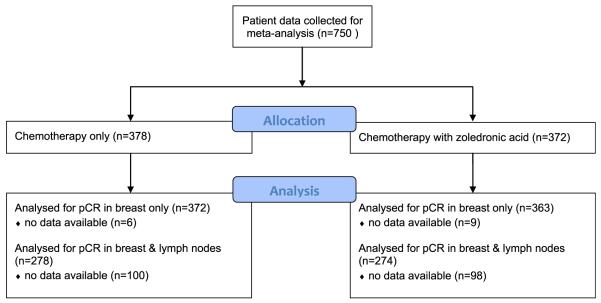

Demographics and tumour characteristics of the pooled population are summarised in Table 1. A total of 735 and 552 patients were included for the pCRb and pCR analysis respectively. pCRb data were available from 735 patients (CONSORT diagram: Fig. 1). The median age of our pooled population was 48 (range 25–75). Thirty seven percent of the included women were postmenopausal (Supplementary file: definitions of postmenopausal status in included studies). Seventy three percent of the tumours were ER-positive and 8% were Human Epidermal growth factor Receptor 2 (HER2)-positive. Nineteen percent of the tumours were triple-negative (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient and tumour characteristics of the pooled population.

| Pooled population | ||

|---|---|---|

| N | 750 | |

| Median age(range) | 48 (25–75) | |

| T-status | T1/T2 | 374 (49.9) |

| T3/T4 | 375 (50.0) | |

| Unknown | 1 (0.1) | |

| N statusa | N– | 223 (29.7) |

| N+ | 333 (44.4) | |

| Unknown | 194 (25.9) | |

| ER-status | ER– | 201 (26.8) |

| ER+ | 548 (73.1) | |

| Unknown | 1 (0.1) | |

| PR status | PR– | 239 (39.1) |

| PR+ | 397 (52.2) | |

| Unknown | 60 (8.0) | |

| HER2-status | HER2– | 623 (83.1) |

| HER2+ | 58 (7.7) | |

| Unknown | 69 (9.2) | |

| Triple-negative tumour | Yes | 141 (18.8) |

| No | 514 (68.5) | |

| Unknown | 95 (17.7) | |

| Postmenopausal | Yes | 277 (36.9) |

| No | 455 (60.7) | |

| Unknown | 18 (2.4) |

ER, oestrogen receptor; PR, progesterone receptor.

High number of missings as nodal status was not prospectively collected in each study.

Fig. 1.

CONSORT diagram. pCR, pathological complete response.

3.2. Trial-level analysis

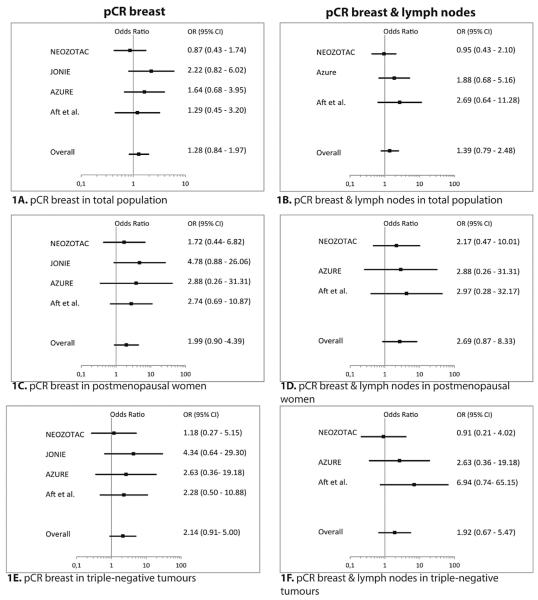

Study effects among trials were homogeneous (I2 = 0%, p = 0.44), and for this reason a fixed-effects model was used for analysis. In the total pooled population of patients with early BC, the addition of ZA to neoadjuvant CT did not increase pCRb (OR = 1.28, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.84–1.97) or pCR (OR = 1.39, 95% CI 0.79–2.48) (Fig. 2A, B). pCR and pCRb were next investigated separately in pre/perimenopausal and postmenopausal women. A non-significant benefit of the addition of ZA with regards to pCR and pCRb was observed in postmenopausal patients (pCR: OR = 2.69, 95% CI 0.87–8.33; pCRb: OR 1.99, 95% CI 0.90–4.39), but not in pre/perimenopausal patients (pCR: OR = 0.93, 95% CI 0.46–1.90; pCRb: OR = 1.07, 95% CI 0.62–1.86) (Fig. 2C, D).

Fig. 2.

Forest plots of the effects of zoledronic acid on pCR (1A, 1C, 1E) and pCRb (1B, 1D, 1F). Odds ratios are adjusted for T-status and ER-status. ER, oestrogen receptor; pCR, pathological complete response; pCRb, pathological complete response in the breast; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

3.3. Individual patient-data analysis

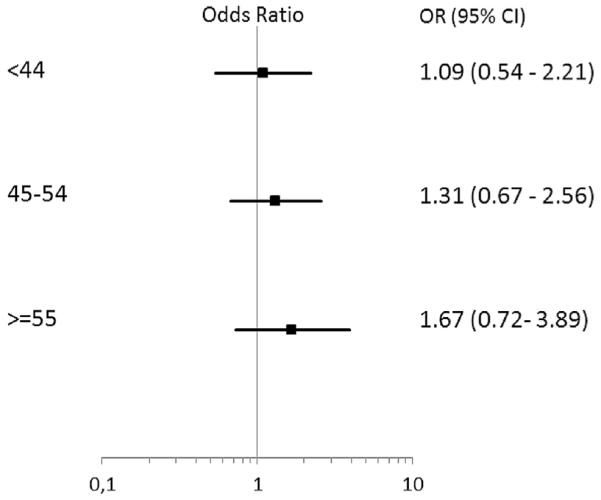

In the individual patient-data analysis, no difference in pCRb or pCR rates with the addition of ZA was observed in the total study population (Table 2). However, a significantly greater proportion of postmenopausal patients attained pCRb if treated with the addition of ZA (10.8% versus 17.7%, OR 2.14, 95% CI 1.01–4.55, p = 0.048). For pCR, a tendency towards better response after zoledronic administration (7.8% versus 14.6%, OR –2.62, 95% CI 0.90–7.62, p = 0.076) was observed. However, the data were not sufficient to show a significant interaction between the intervention (ZA) and postmenopausal status as regards treatment effect. (p-value for interaction = 0.17). A post hoc exploratory analysis based on age as a surrogate for menopausal status suggested that the benefit of ZA addition increases with age (Fig. 3). However, this should be considered as highly exploratory as no significant interaction was observed between the age categories and ZA treatment (p-value for interaction 0.46).

Table 2.

pCRb and pCR in the total population and subgroups of interest.

| Chemotherapy only |

Chemotherapy + ZA |

Odd’s ratio | 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pCRb/total | Percentage | pCRb/total | Percentage | |||

| pCR in breast | ||||||

| Total population | 50/372 | 13.4% | 60/363 | 16.5% | 1.31 | 0.86–1.99 |

| Postmenopausal patients | 14/130 | 10.8% | 25/141 | 17.7% | 2.14 | 1.01–4.55a |

| Pre/peri menopausal patients | 34/232 | 14.7% | 34/214 | 15.9% | 1.09 | 0.64–1.84 |

| Triple-negative breast cancer | 13/70 | 18.6% | 22/67 | 32.8% | 2.16 | 0.97–4.84 |

| pCR | ||||||

| Total population | 27/278 | 9.7% | 36/274 | 13.1% | 1.43 | 0.82–2.49 |

| Postmenopausal patients | 7/90 | 7.8% | 15/103 | 14.6% | 2.62 | 0.90–7.62 |

| Pre/peri menopausal patients | 19/178 | 10.7% | 20/163 | 12.3% | 1.13 | 0.57–2.25 |

| Triple-negative breast cancer | 9/52 | 17.3% | 16/51 | 31.4% | 2.00 | 0.78–5.17 |

pCRb, pathological complete response in the breast; ZA, zoledronic acid; pCR, pathological complete response; CI, confidence interval.

Data from the individual patient data analysis.

Statistically significant.

Fig. 3.

pCRb on the basis on age in the individual patient data analysis. P-value for interaction = 0.46. pCRb, pathological complete response in the breast; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

4. Discussion

In our meta-analysis we did not observe a benefit in the pCR or pCRb rate in the overall patient population when ZA was added to neoadjuvant CT in women with clinical stage II/III BC. Our study provides the first data indicating a statistically significant benefit of the addition of ZA to neoadjuvant CT on pCR in postmenopausal patients with early BC. Our findings are in concordance with observations in the adjuvant setting, where the addition of ZA to systemic therapy has shown survival benefit in postmenopausal patients with low levels of reproductive hormones [1,8,9].

The precise biological mechanism that enables a specific anti-tumour effect of ZA in patients with low reproductive hormone levels is still unknown. Postmenopausal women are known to have an increased receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa β ligand (RANKL) to osteoprotegerin ratio, thereby promoting osteoclastogenesis and accelerating bone turnover [10]. During bone resorption, growth factors and cytokines, such as insulin-like growth factors and transforming growth factor β, are released from the bone which may stimulate proliferation and attract tumour cells [11]. Since, the main effect of ZA is inhibition of bone resorption, this might explain why postmenopausal women, with an increased bone turnover, benefit from ZA therapy. Another explanation might be related to an immunomodulatory effect of ZA. Low oestrogen levels induce an inflammatory response with an increase in immune cells such as macrophages and T-cells [12]. Tumour associated macrophages (TAM) or M2 macrophages assist tumour progression [13,14]. Bisphosphonates reverse the TAM phenotype from pro-tumoural M2 to tumouricidal M1 and help deplete these M2 macrophages [15]. In addition to this, in a preclinical model it was observed that ZA was more toxic to human macrophages rather than to BC cells [16]. A study by Junankar et al. showed, using two-photon microscopy, that outside of the skeleton bisphosphonates are likely to be taken up by TAMs. They found that bisphosphonates initially binds to areas of micro-calcifications and can be engulfed by TAMs [17]. This might be a mechanism through which ZA could affect primary breast tumour growth. Furthermore, stimulated T-cells may interact with antigen presenting cells, attack tumour cells and express and secrete RANKL, which can contribute to the anti-tumour effect of ZA. Consequently, the combination of a tumour microenvironment with increased immune cells, RANKL and bone turnover, caused by oestrogen deprivation, might explain why ZA has an anti-tumour effect when administered as an adjunct to neoadjuvant CT that appears restricted to postmenopausal patients. Several other mechanisms have been proposed as explanation for direct anti-tumour effects of ZA, such as direct cytotoxic and pro-apoptotic effects [18]. Also, preclinical studies have suggested that bisphosphonates may inhibit tumour angiogenesis [19–22]. Clearly, more research is warranted elucidating the potential direct anti-tumour effects of ZA. In addition, it may also be possible that ZA exerts indirect anti-tumour effects, via its impact on the bone microenvironment. However, it is unclear how changes in the bone microenvironment can affect tumour decrease in the more distal breast. Bone acts a reservoir for paracrine tumour suppressors such as activin. Activin is inhibited by follistatin and inhibin, which is decreased in postmenopausal women. Winter et al. published exploratory data showing that the activin inhibitor follistatin is decreased after short term ZA treatment [23].

Another point of potential interest for further investigation is the exact timing of ZA. The preclinical mice study by Ottewell et al. showed that infusion of ZA 24 h after doxorubicin infusion resulted in enhanced abolishment of tumour growth, suggesting that ‘priming’ with doxorubicin made cells more sensitive to anti-tumoural effects of ZA [8]. In three of the four studies included in our meta-analysis (JONIE, AZURE, Aft et al.) ZA was infused directly after CT. In the NEOZOTAC study ZA was infused directly after CT during hospital admission or within 24 h by homecare. In the latter study no significant difference was observed between the direct infusion and infusion 1 d later within 24 h [5]. In future studies it would be interesting to also investigate if ZA administration after 24 h is more effective than when given directly after CT infusion.

There are some limitations to our study. Our meta-analysis relied on slightly differing definitions of menopausal status as defined by each of the included studies. As confirmation of our findings, we performed an analysis based on individual patient age as a surrogate for menopausal status which showed similar results to the analyses using trial-defined menopausal status. Although our study represents the largest population to date, the sample size of our meta-analysis was not sufficient to prove a significant effect of ZA on pCR in breast and lymph nodes, as this end-point was not collected in one of the included studies. In addition, our data were not sufficient to show statistical interaction between postmenopausal status and ZA intervention as regards pCR, although clear differences, consistent with findings in the adjuvant setting, were found in favour of the postmenopausal subset of patients. Therefore, based on the data presented in our study, it cannot yet be conclusively stated that ZA has a direct anti-tumour effect in the neoadjuvant setting and survival analyses of the studies have to be awaited.

Further translational research is necessary and ongoing in order to elucidate the specific anti-tumour mechanism of ZA, especially concerning the alleged immunomodulatory role, in order to select those patients that would benefit most from including ZA in their treatment regimen. The NEOZOL study for example, aims to evaluate changes in vascular endothelial growth factor and gamma-delta T-cell activity (NCT01367288) [24].

Another important remaining question is whether the beneficial effect in postmenopausal women during neoadjuvant treatment will translate into improved survival, especially in cases with triple-negative BC. Reduction of dissemination in the bone microenvironment may provide survival benefit. As the data mature over the next few years, an update of this meta-analysis with long term follow up results will hopefully provide a conclusive answer to this.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are greatly indebted to all the patients and their physicians and supporting staff for participation in these clinical trials.

Funding

For details of study funding we refer to the original manuscripts of the four participating studies. No additional funding was received for this meta-analysis.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Dr. J.R. Kroep received a grant of Novartis for the NEOZOTAC trial. Prof. Dr. R.E. Coleman received payment from Novartis for expert testimony. Dr. S. Hinsley received grant support for the Azure trial.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2015.10.011

References

- [1].Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group Adjuvant bisphosphonate treatment in early breast cancer: meta-analyses of individual patient data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2015 Oct 3;386(10001):1353–61. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60908-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Coleman RE, Winter MC, Cameron D, Bell R, Dodwell D, Keane MM, et al. The effects of adding zoledronic acid to neoadjuvant chemotherapy on tumour response: exploratory evidence for direct anti-tumour activity in breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2010 Mar 30;102(7):1099–105. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Aft R, Naughton M, Trinkaus K, Watson M, Ylagan L, Chavez-MacGregor M, et al. Effect of zoledronic acid on disseminated tumour cells in women with locally advanced breast cancer: an open label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010 May;11(5):421–8. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70054-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Horiguchi J, Hasegawa Y, Miura D, Ishikawa T, Mitsuhiro H, Hayashi M, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing zoledronic acid plus chemotherapy with chemotherapy alone as a neoadjuvant treatment in patients with HER2-negative primary breast cancer. Abstract 1029 ASCO Annual Meeting; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Charehbili A, van de Ven S, Smit VT, Meershoek-Klein-Kranenbarg EM, Hamdy NA, Putter H, et al. Addition of zoledronic acid to neoadjuvant chemotherapy does not enhance tumor response in patients with HER2 negative stage II/III breast cancer: the NEOZOTAC trial (BOOG 2010-01) Ann Oncol. 2014 Feb 27; doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ottewell PD, Brown HK, Jones M, Rogers TL, Cross SS, Brown NJ, et al. Combination therapy inhibits development and progression of mammary tumours in immunocompetent mice. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012 Jun;133(2):523–36. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1782-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].von Minckwitz G, Untch M, Blohmer JU, Costa SD, Eidtmann H, Fasching PA, et al. Definition and impact of pathologic complete response on prognosis after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in various intrinsic breast cancer subtypes. J Clin Oncol. 2012 May 20;30(15):1796–804. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.8595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Gnant M, Mlineritsch B, Stoeger H, Luschin-Ebengreuth G, Heck D, Menzel C, et al. Adjuvant endocrine therapy plus zoledronic acid in premenopausal women with early-stage breast cancer: 62-month follow-up from the ABCSG-12 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011 Jul;12(7):631–41. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70122-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Coleman RE, Marshall H, Cameron D, Dodwell D, Burkinshaw R, Keane M, et al. Breast-cancer adjuvant therapy with zoledronic acid. N Engl J Med. 2011 Oct 13;365(15):1396–405. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hadji P, Coleman R, Gnant M, Green J. The impact of meno-pause on bone, zoledronic acid, and implications for breast cancer growth and metastasis. Ann Oncol. 2012 Nov;23(11):2782–90. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Winter MC, Holen I, Coleman RE. Exploring the anti-tumour activity of bisphosphonates in early breast cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008 Aug;34(5):453–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Weitzmann MN, Pacifici R. Estrogen deficiency and bone loss: an inflammatory tale. J Clin Invest. 2006 May;116(5):1186–94. doi: 10.1172/JCI28550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Allavena P, Mantovani A. Immunology in the clinic review series; focus on cancer: tumour-associated macrophages: undisputed stars of the inflammatory tumour microenvironment. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012 Feb;167(2):195–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04515.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Dijkgraaf EM, Heusinkveld M, Tummers B, Vogelpoel LT, Goedemans R, Jha V, et al. Chemotherapy alters monocyte differentiation to favor generation of cancer-supporting M2 macrophages in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2013 Apr 15;73(8):2480–92. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Rogers TL, Holen I. Tumour macrophages as potential targets of bisphosphonates. J Transl Med. 2011;9:177. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Rietkotter E, Menck K, Bleckmann A, Farhat K, Schaffrinski M, Schulz M, et al. Zoledronic acid inhibits macrophage/microglia-assisted breast cancer cell invasion. Oncotarget. 2013 Sep;4(9):1449–60. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Junankar S, Shay G, Jurczyluk J, Ali N, Down J, Pocock N, et al. Real-time intravital imaging establishes tumor-associated macrophages as the extraskeletal target of bisphosphonate action in cancer. Cancer Discov. 2014 Oct 13; doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ottewell PD, Monkkonen H, Jones M, Lefley DV, Coleman RE, Holen I. Antitumor effects of doxorubicin followed by zoledronic acid in a mouse model of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008 Aug 20;100(16):1167–78. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Fournier P, Boissier S, Filleur S, Guglielmi J, Cabon F, Colombel M, et al. Bisphosphonates inhibit angiogenesis in vitro and testosterone-stimulated vascular regrowth in the ventral prostate in castrated rats. Cancer Res. 2002 Nov 15;62(22):6538–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Stresing V, Fournier PG, Bellahcene A, Benzaid I, Monkkonen H, Colombel M, et al. Nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates can inhibit angiogenesis in vivo without the involvement of farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase. Bone. 2011 Feb;48(2):259–66. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Santini D, Vincenzi B, Galluzzo S, Battistoni F, Rocci L, Venditti O, et al. Repeated intermittent low-dose therapy with zoledronic acid induces an early, sustained, and long-lasting decrease of peripheral vascular endothelial growth factor levels in cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2007 Aug 1;13(15 Pt 1):4482–6. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Santini D, Vincenzi B, Dicuonzo G, Avvisati G, Massacesi C, Battistoni F, et al. Zoledronic acid induces significant and long-lasting modifications of circulating angiogenic factors in cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2003 Aug 1;9(8):2893–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Winter MC, Wilson C, Syddall SP, Cross SS, Evans A, Ingram CE, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with or without zoledronic acid in early breast cancer—a randomized biomarker pilot study. Clin Cancer Res. 2013 May 15;19(10):2755–65. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24]. [accessed 20.11.14];Website. Clinicaltrials.gov.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.