Abstract

Introduction:

Spontaneous vasoconstriction of the extracranial internal carotid artery (SVEICA) is a rare cause of cerebral infarction. Most patients with SVEICA suffer recurrent attacks of vasoconstriction. The standard treatment for this condition has not been established and its long-term prognosis is unclear.

Case Report:

A 25-year-old man with a history of refractory vasospasm angina presented with transient alternating hemiplegia in both the right and left side. Serial carotid ultrasonography examinations showed severe transient stenosis or occlusion of cervical internal carotid arteries on 1 or both sides, with and without neurological symptoms. This condition resolved completely within 1 day to 1 week. The patient did not present any other risk factors for atherosclerosis and was diagnosed with SVEICA. The treatment with calcium antagonists and nitrates did not prevent the attacks. Administration of a corticosteroid substantially reduced the vasospasm attacks.

Conclusions:

SVEICA is intractable and difficult to diagnose. It has been reported that SVEICA sometimes complicates coronary artery disease, as observed in this case. The present case demonstrated the effectiveness of corticosteroid treatment against this disease. Serial ultrasonography examinations helped us to diagnose and follow-up the vasospasm attacks.

Key Words: refractory vasospasms, extracranial internal carotid artery, corticosteroid, ultrasonography, cerebral infarction

Spontaneous vasoconstriction of extracranial internal carotid artery (SVEICA) is known as a rare and refractory cause of cerebral infarction.1–12 However, the etiology and effective treatment for this disease have not been established. We present a case of SVEICA, which had developed over 10 years and was successfully treated using a corticosteroid. Serial carotid ultrasonography (US) examination was effective in the diagnosing the vasospasms and evaluating response to the treatment.

CASE REPORT

A 25-year-old man presented with transient alternating hemiplegia at our hospital. He had frequent chest pains caused by coronary artery spasms. He had suffered an acute anterior myocardial infarction with thrombus 6 years previously and undergone an intensive medical therapy. A coronary artery stent had been placed, but the primary and secondary stent occlusions occurred within 1 year. He was subsequently treated with a calcium channel blocker (CCB) and an anticoagulant drug. He developed right hemiparesis and aphasia 2 years previously. Acute cerebral infarcts in both the frontoparietal lobes were detected by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at that time. Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) revealed severe stenosis in the left extracranial ICA. Three days later, MRA showed no abnormality in the left ICA, but a severe stenosis in the right ICA. The patient experienced no traumatic events and no intramural hematoma could be detected. The results of blood and cerebrospinal fluid analysis were normal. Antiplatelet therapy was added on the basis of the diagnosis of spontaneous vasospasms. Since his first ischemic stroke event, the patient had suffered several attacks of transient hemiparesis in the right or left side and reported of feeling lethargic at least once in a month. He was a nonsmoker and had no family history of neurological or cardiovascular diseases.

On admission to the hospital, the results of blood analysis, including the examination for collagen diseases and coagulopathies, revealed no abnormalities except for a high level of nonspecific immunoglobulin E. The patient was alert and no new neurological abnormalities were observed using MRI and MRA. Carotid and transcranial US examinations were performed once in a day to evaluate the vasospasms of cervical ICA. US results revealed a stenotic portion of the ICA at 2 to 5 cm from its origin and an increased peak flow velocity, in agreement with MRA data. The blood flow in the middle cerebral artery (MCA), evaluated using transcranial color-coded sonography, was maintained despite occurrence of ICA spasms. Several new episodes of ICA spasms in 1 or both sides, with and without any neurological symptoms, were detected. Although the dose of CCB was increased and supplemented by nitrate treatment, the vasospasms continued for the periods of 1 day to 1 week.

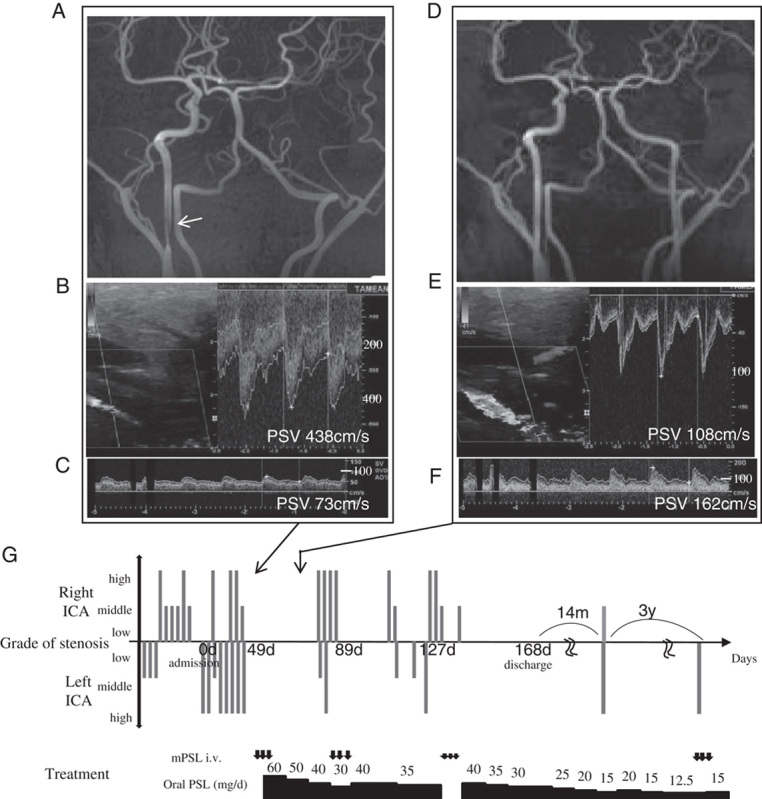

On the 49th day in the hospital, bilateral ICA vasospasms were detected using US and MRA (Figs. 1A, B). Furthermore, transcranial color-coded sonography revealed a reduction in the blood flow velocity in the left MCA, with a poststenotic pattern flow (Fig. 1C). CCB and nitrate treatment (both intravenous and oral administration) did not suppress ICA vasospasms. Then, steroid pulse therapy (methylprednisolone 1000 mg/d for 3 d) and subsequently oral corticosteroid therapy (prednisolone 60 mg/d) was started. Two days later, MRA and US examinations showed the complete resolution of vasospasms (Figs. 1D–F).

FIGURE 1.

A–C, MRA and US images on the 49th day of hospitalization. MRA revealed severe stenosis of bilateral ICAs. Stenosis of the right ICA was about 5 cm above its origin (A, arrow). No flow was detected in the left ICA (using MRA) because of severe stenosis (A). US showed severe bilateral stenosis of ICAs. PSV increased to 438 cm/s in the left ICA (B). TCCS revealed that the flow velocity in the left MCA dropped to 45% (PSV 73 cm/s) with poststenotic flow pattern (C). D–F, MRA and US images after steroid pulse therapy. MRA revealed no abnormality (D). US revealed normal findings in the left ICA (PSV 108 cm/s) (E). The PSV in the left MCA increased (F) to 162 cm/s. G, Time course of the disease (upper: grade of stenosis, lower: treatment). The grade of stenosis was calculated as in North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET) on the basis of MRA or assessed by PSV with US and defined as follows: high-grade stenosis: NASCET≥70% or PSV≥200 cm/s, moderate-grade stenosis: 50%≤NASCET<70% or 150 cm/s<PSV<200 cm/s, and low-grade stenosis: NASCET<50% or PSV<150 cm/s. PSV, peak flow velocity; mPSL, methylprednisolone; IV, intravenous administration of methylprednisolone; PSL, prednisolone.

After we had tapered the corticosteroid dose to 15 mg/d during the next 14 months, the patient returned to the hospital with a right-hand limb shaking signs. MRA examination revealed a severe stenosis of the left ICA. The dosage of the corticosteroid was increased to 20 mg/d and tapered again to 12.5 mg/d. Three years later, the patient was hospitalized again with limb shaking. US revealed the left ICA occlusion due to SVEICA. Intravenous administration of methylprednisolone (250 mg/d for 3 d) completely resolved the left ICA spasms within a day. The patient has been free of complaints and living a normal social life, except for 2 short attacks, for 4 years since the administration of the corticosteroid. He is being treated with an oral corticosteroid (15 mg/d) and is surviving without cervical vasospasms or cardiovascular events.

DISCUSSION

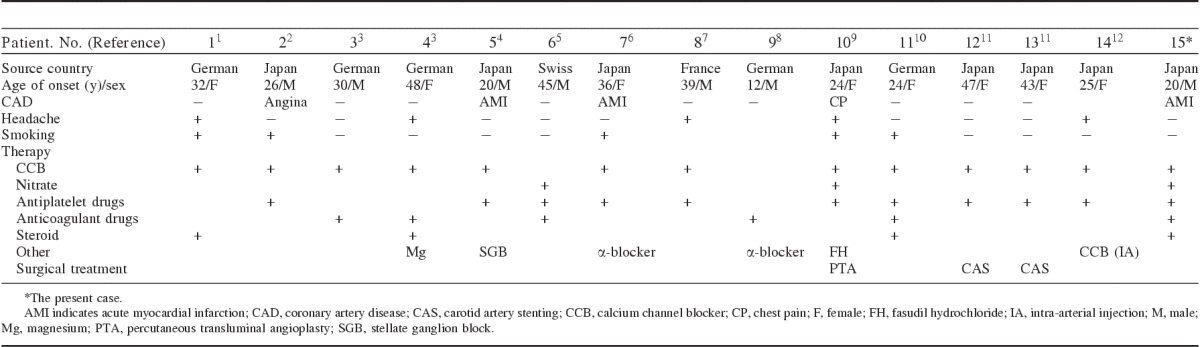

Table 1 summarizes the data from previous reports on SVEICA, including the present case. The unilateral or bilateral ICA vasospasms were resolved within a short time, and there were no other radiologic findings reported. Only a few patients with SVEICA had headaches, which were not associated with vasospasms. Some patients, including our patient, suffered from a coronary artery disease.2,4,6,9 The patient described by Yoshimoto et al6 was diagnosed with vasospastic angina using acetylcholine test.

TABLE 1.

Previous Reports of Spontaneous Vasoconstriction in Extracranial Internal Carotid Arteries Including the Present Case

The mechanism of SVEICA is unclear, although different diagnoses such as aortic dissection, reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome, infections, connective tissue disease, pheochromocytoma, migraine, and coagulopathy were ruled out in most cases. In the patient reported by Kuzumoto et al,2 the disease appeared to be associated with smoking; however, vasospasms recurred after he quit smoking.

All the patients had treatment suitable for the cerebral infarction in the acute stage. Some reports have shown the effectiveness of stellate ganglion block,4 balloon angioplasty,9 carotid artery stenting,11 and intra-arterial injection of CCB.12 However, most patients suffered recurrences of vasospasms despite their chronic phase medication, such as treatment with CCB, antiplatelet, intravenous magnesium, and antiepileptic drugs. In 1 case, administration of α-blocker8 was effective. Steroid therapy was effective in 2 cases1,3 and ineffective in 1.10 Takagi et al reported that, in some patients with an allergic tendency, their recurrent vasospastic angina was completely controlled by corticosteroids administration, and they have suggested that the coronary spasms may be induced by arterial hyperreactivity caused by local inflammation; corticosteroids would suppress the allergic response in the coronary artery.13 Corticosteroids may also be effective in the SVEICA patients for the same reason. A recurrence of vasospasms after a reduction in the dose of oral corticosteroids has been reported1,3; it was also observed in our case, suggesting that autoimmune response may be associated with SVEICA.

We performed daily carotid and transcranial US examination to screen for the spasms and evaluate the response to treatment because vasospasms often occurred asymptomatically and resolved rapidly. Our case suggested that daily US examination of the patients with suspected vasospasms of ICAs could detect the rapid morphologic changes.

Standard treatment and long-term prognosis for SVEICA are yet to be determined. The present case showed that corticosteroids might be effective, particularly for the patients with allergic tendencies. More cases are required to solve the etiology of SVEICA and to elucidate a standard treatment.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arning C, Schrattenholzer A, Lachenmayer L. Cervical carotid artery vasospasms causing cerebral ischemia: detection by immediate vascular ultrasonographic investigation. Stroke. 1998;29:1063–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuzumoto Y, Mitsui Y, Ueda H, et al. Vasospastic cerebral infarction induced by smoking: a case report. No To Shinkei. 2005;57:33–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janzarik WG, Ringleb PA, Reinhard M, et al. Recurrent extracranial carotid artery vasospasms: report of 2 cases. Stroke. 2006;37:2170–2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yokoyama H, Yoneda M, Abe M, et al. Internal carotid artery vasospasm syndrome demonstration by neuroimaging. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:888–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mosso M, Jung HH, Baumgartner RW. Recurrent spontaneous vasospasm of cervival carotid, ophthalmic and retinal arteries causing repeated retinal infarcts: a case report. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007;24:381–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshimoto H, Matsuo S, Umemoto T, et al. Idiopathic carotid and coronary vasospasm: a new syndrome? J Neuroimaging. 2011;21:273–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magnin E, Mouton S, Abouaf L, et al. Idiopathic vasospastic angiopathy of the internal carotid arteries: a rarely recognized cause of ischemic stroke in young individuals. Rev Neurol. 2011;1267:626–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moller S, Hilz MJ, Blinzler C, et al. Extracranial internal carotid artery vasospasm due to sympathetic dysfunction. Neurology. 2012;78:1892–1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dembo T, Tanahashi N. Recurring extracranial internal carotid artery vasospasm detected by intravascular ultrasound. Intern Med. 2012;51:1249–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sigrid W, Andreas K, Markus L, et al. Recurrent strokes due to transient vasospasms of the extracranial internal carotid artery. Case Rep Neurol. 2013;5:143–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujimoto M, Itokawa H, Moriya M, et al. Treatment of idiopathic cervical internal carotid artery vasospasms with carotid artery stenting: a report of 2 cases. JNET. 2013;7:24–31. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimoda Y, Fujimura M, Kimura N, et al. Recurrent extracranial internal carotid artery vasospasm diagnosed by serial magnetic resonance angiography and superselective transarterial injection of a calcium channel blocker. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23:e383–e387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takagi S, Goto Y, Hirose E, et al. Successful treatment of refractory vasospastic angina with corticosteroids: coronary arterial hyperactivity caused by local inflammation? Circ J. 2004;68:17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]