Abstract

Background

Aberrant DNA methylation may promote prostate carcinogenesis. We investigated epigenome-wide DNA methylation profiles in prostate cancer (PCa) compared to adjacent benign tissue to identify differentially methylated CpG sites.

Methods

The study included paired PCa and adjacent benign tissue samples from 20 radical prostatectomy patients. Epigenetic profiling was done using the Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip. Linear models that accounted for the paired study design and False Discovery Rate Q-values were used to evaluate differential CpG methylation. mRNA expression levels of the genes with the most differentially methylated CpG sites were analyzed.

Results

In total, 2,040 differentially methylated CpG sites were identified in PCa versus adjacent benign tissue (Q-value <0.001), the majority of which were hypermethylated (n = 1,946; 95%). DNA methylation profiles accurately distinguished between PCa and benign tissue samples. Twenty-seven top-ranked hypermethylated CpGs had a mean methylation difference of at least 40% between tissue types, which included 25 CpGs in 17 genes. Furthermore, for ten genes over 50% of promoter region CpGs were hypermethylated in PCa versus benign tissue. The top-ranked differentially methylated genes included three genes that were associated with both promoter hypermethylation and reduced gene expression: SCGB3A1, HIF3A, and AOX1. Analysis of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data provided confirmatory evidence for our findings.

Conclusions

This study of PCa versus adjacent benign tissue showed many differentially methylated CpGs and regions in and outside gene promoter regions, which may potentially be used for the development of future epigenetic-based diagnostic tests or as therapeutic targets.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, DNA methylation, mRNA expression, tumor, benign

INTRODUCTION

DNA methylation of CpG sites (CpGs) is a well-known epigenetic mechanism for control of gene expression (1,2). CpGs are commonly found in clusters called CpG islands, which are often in gene promoter regions. While CpGs outside islands are usually methylated, CpGs island promoter regions are typically unmethylated (1). Hypermethylation of gene promoter regions can lead to transcriptional silencing. Both losses and gains of DNA methylation have been associated with cancer, including prostate cancer (PCa) (1,3). Differential DNA methylation outside gene promoter regions (e.g., the gene body) may also play a critical role in gene regulation (4,5).

Several candidate gene studies have investigated gene promoter methylation in relation to PCa (3,6). These studies reported a number of genes that are hypermethylated in PCa compared to adjacent non-cancer tissue, most notably GSTP1 (7). This earlier work led to the development of an epigenetic test that measures the methylation levels of three genes, GSTP1, APC, and RASSF1, for the detection of PCa (8). However, because these previous studies used a candidate gene approach focused on selected genes, other important differentially methylated CpG sites and genes involved in PCa growth may have been missed.

Several studies have taken a more comprehensive approach to investigate DNA methylation in PCa (9–16). These studies used array-based platforms with varying degrees of epigenome-wide coverage including the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation27 (HM27) BeadChip, which only interrogates gene promoter regions, and the more extensive HumanMethylation450 (HM450) BeadChip, which also interrogates regions outside gene promoters such as gene body and intergenic regions (9,11–13,16). Two small studies have used the HM450 platform for epigenome-wide DNA methylation profiling of PCa. The first study included 19 PCa samples and 4 benign samples (matched to 4 of the PCa samples) (11), and the second study included paired PCa and benign samples from 6 patients (9). Both studies identified a large number of differentially methylated CpGs, which were mostly hypermethylated in cancer samples; but these findings have not been replicated in independent datasets.

The goal of the present study was to evaluate DNA methylation profiles in paired PCa and adjacent benign tissue samples. We aimed to find novel differentially methylated CpGs and regions in PCa, and determine if findings from previous smaller studies could be replicated in our larger dataset. Importantly, the potential biological effect of the top-ranked differentially methylated CpGs/genes on mRNA expression was evaluated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Prostate cancer and adjacent benign tissue samples

The study included paired PCa and histologically benign tissue samples from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue blocks. The samples were available from patients enrolled in population-based studies of PCa, who had radical prostatectomy as their primary treatment for clinically localized disease (17,18). Baseline patient data were collected using an in-person interview. Information on clinicopathological parameters (e.g., Gleason score, disease stage, diagnostic prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level) was obtained from the Seattle-Puget Sound Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) cancer registry. All patients signed informed consent and procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

Sample preparation and DNA extraction

The FFPE blocks from radical prostatectomy specimens were used to make hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained slides, which were reviewed by a PCa pathologist to confirm the presence and location of PCa within the blocks. Areas containing ≥75% PCa cells had two 1-mm tumor tissue cores taken for DNA extraction. Adjacent non-tumor (histologically benign) prostate tissue cores were taken using the same procedure. Extraction of cancer and benign DNA from the cores was completed using the RecoverAll Total Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit (Ambion/Applied Biosciences). The standard manufacturer’s protocol was followed, except that the elution step was performed twice to maximize the DNA yield. Purified DNA was quantified (PicoGreen) and stored at −80°C until samples were shipped to Illumina, Inc. (San Diego, CA) for completion of assays.

DNA methylation arrays

Samples were bisulfite-converted using the EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Controls on the array were used to track the bisulfite conversion efficiency. The Infinium HumanMethylation450 (HM450) BeadChip array (Illumina, Inc.) was used to measure epigenome-wide DNA methylation using beads with target-specific probes designed to interrogate individual CpGs (No. of CpGs >480,000) on bisulfite-converted genomic DNA. Our analysis of 20 matched PCa and benign tissue samples was part of a larger project that has been described previously (19).

HM450 methylation data from The Cancer Genome Atlas

Data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) were used to verify the most significant findings from the methylation analysis. HM450 data (level 3) were downloaded from the TCGA data portal (https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/tcga/). Forty-six patients with both a primary PCa and benign (‘solid tissue normal’) tissue sample were available for DNA methylation analysis. Patients with benign tissue taken from the seminal vesicles were excluded (n = 4).

Gene expression arrays

Matched tissue samples from the same patients were used to investigate gene expression of the top-ranked differentially methylated genes. PCa and adjacent histologically benign cores for RNA purification (two 1-mm cores from each site) were sampled as per the approach described above for DNA. RNA was isolated using the RNeasy® FFPE Kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA), quantified using RiboGreen, and stored at −80°C. Expression profiling was done at Illumina using the Whole-Genome cDNA-mediated Annealing, Selection, extension, and Ligation (DASL®) HT Assay (Illumina, Inc.).

Data processing and analysis

The Bioconductor minfi package was used to analyze the HM450 data (20). Failed samples were identified using the detection P-value metric according to the standard protocols (Illumina, Inc.). A sample was excluded if less than 95% of the CpGs on the array for that sample were detected with a detection P-value <0.05; no samples had to be excluded based on this criterion. Next, we filtered out CpGs with an average detection P-value >0.01 (n = 3,715) and non-CpG probes (n = 2,799). Based on this, 478,998 CpGs remained for analysis. The data were normalized using subset-quantile within array normalization (SWAN) (21), and potential batch effects were removed using ComBat (22).

Methylation β-values were calculated, which represent the methylation level at each CpG locus: [intensity of the methylated allele/(intensity of the unmethylated allele + intensity of the methylated allele + 100)]. β-values range from 0 (unmethylated) to 1 (100% methylated) (23). The β-values were used to calculate the percentage methylation difference between cancer and benign tissue. Methylation M-values were calculated by taking the logit transformation of the β-values (23). Linear regression (Bioconductor limma package) with an empirical Bayes approach, and using the methylation M-values was conducted to assess which CpGs were associated with PCa (24). The paired study design (cancer and benign tissue from the same patients) was accounted for by including a variable for study pair in the model, making this approach analogous to the paired t-test (24). The same approach was used to analyze the gene expression data. False Discovery Rate (FDR) Q-values were calculated to control the proportion of false positives, and a Q-value of less than 0.001 was considered statistically significant (25). Genome annotation data for the HM450 array were used (26). A gene promoter was defined as: TSS1500 and TSS200 (1500 base pairs (bp) and 200 bp upstream of the transcription start site), 5’UTR (5’ untranslated region), and exon 1. This definition was used because methylation in any of these regions can result in gene silencing (3). Manhattan and volcano plots were constructed to visualize the data. Unsupervised clustering was used to determine whether DNA methylation profiles separated cancer from benign tissue samples. In addition, the proportion of hyper- and hypo-methylated promoter CpGs per gene was calculated and genes with more than 50% hyper- or hypo-methylated promoter CpGs were identified.

Differentially methylated regions (DMRs) were identified using the Probe Lasso method (Bioconductor ChAMP package) (27). The required minimum number of significant CpGs per region was five and a Q-value threshold of 0.001 was applied. Default values were used for the other settings. All statistical analyses were conducted using the R programming language and Bioconductor packages (http://cran.r-project.org/; http://bioconductor.org/).

RESULTS

The mean age of the 20 patients in the study was 56.6 years (Table 1). Patients were European American (n = 18) or African American (n = 2). Half of the patients had a Gleason score of seven or more, and the majority of patients had localized stage disease based on surgical pathology.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of prostate cancer cases

| Variables | No. patients | % patients | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) at diagnosis | 20 | – | 56.60 (8.05) |

| Race | |||

| African American | 2 | 10 | |

| European American | 18 | 90 | |

| Gleason score | |||

| 5–6 | 10 | 50 | |

| 7(3+4) | 8 | 40 | |

| 8–10 | 2 | 10 | |

| Pathological stage | |||

| Local | 13 | 65 | |

| Regional | 7 | 35 | |

| PSA (ng/mL) at diagnosis | |||

| <4 | 1 | 5 | |

| 4–9.9 | 13 | 65 | |

| 10–19.9 | 4 | 20 | |

| 20+ | 1 | 5 |

Abbreviations: PSA, prostate-specific antigen; SD, standard deviation

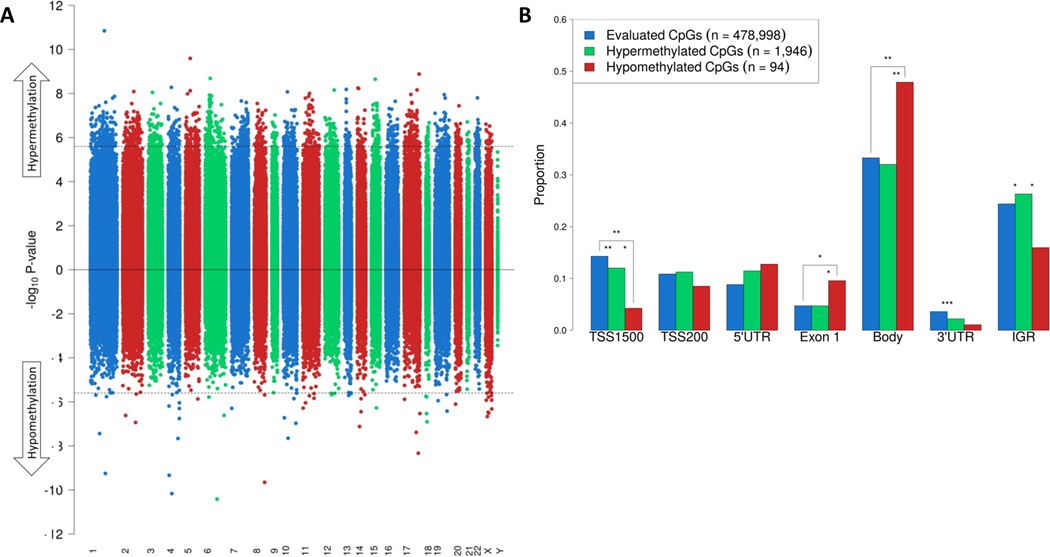

Figure 1 shows a Manhattan plot of PCa versus adjacent benign tissue, illustrating the distribution of differentially methylated CpG sites across the epigenome. In total, 2,040 CpG sites were differentially methylated (Q-value <0.001; Figure 1A). The majority of these CpGs were hypermethylated in PCa versus benign tissue (n = 1,946; 95%). 94 CpGs (5%) were hypomethylated in PCa versus benign tissue. The average methylation difference of the hypermethylated and hypomethylated CpGs was 26% (SD: 7%) and 13% (SD: 8%), respectively. Figure 1B shows the proportion of all evaluated CpG sites and the significantly hyper- and hypo-methylated CpG sites by gene region. Hypomethylated sites were strongly enriched in exon 1 and gene body regions, but were underrepresented in gene promoter (TSS1500) and intergenic regions. Hypermethylated CpGs were underrepresented in the 3’ untranslated regions.

Figure 1.

Differentially methylated CpG sites in PCa versus adjacent benign tissue. A, Manhattan plot of DNA methylation. The horizontal axis shows the chromosomes. Between each chromosome, a 10,000 bp ‘gap’ is shown to aid visualization. The dashed line represents the P-value that corresponds to an FDR Q-value threshold for statistical significance of 0.001. In total, 1,946 hypermethylated and 94 hypomethylated CpGs reached statistical significance. B, the frequencies of all evaluated CpG sites and those that were significantly hyper- and hypo-methylated by gene region. Gene regions are based on Illumina HM450 methylation data. Statistically significant differences are highlighted: P-value <0.05 (*); <0.01 (**); <0.001 (***).

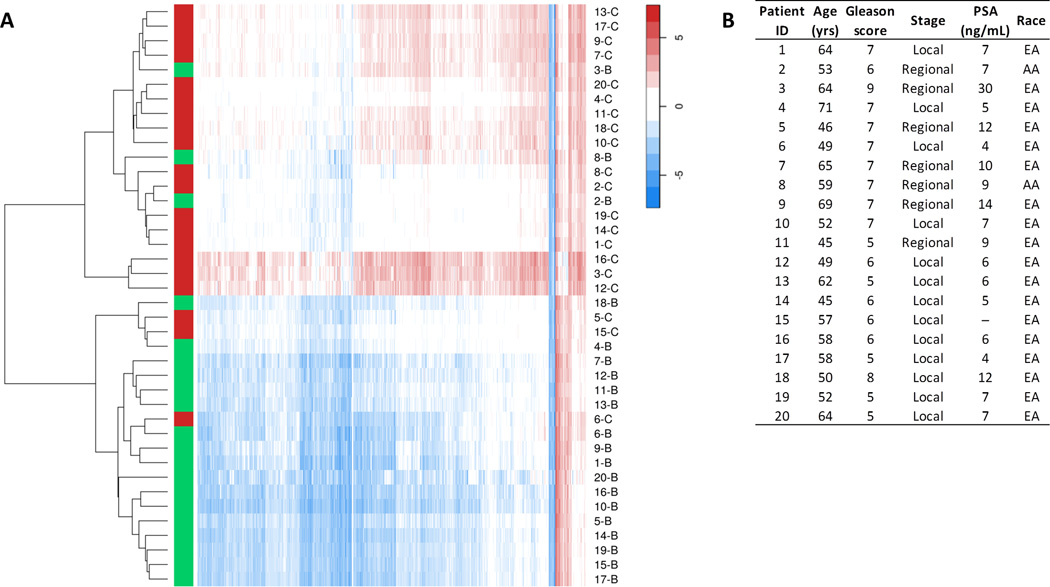

Figure 2A shows a heat map of the 2,040 differentially methylated CpGs by sample. Unsupervised clustering using these CpGs clearly separated PCa from adjacent benign tissue samples. One of the two clusters contained 17 of the 20 PCa samples (85%; Figures 2A and 2B). Interestingly, two of the three benign samples in this cluster of PCa samples were from African-American patients, suggesting that these patients may have different prostate tissue DNA methylation profiles.

Figure 2.

PCa and adjacent benign tissue have distinct DNA methylation profiles. A, heat map of DNA methylation levels in PCa (red) and adjacent benign tissue (green), based on unsupervised clustering. The 2,040 differentially methylated CpGs in PCa versus benign tissue (FDR Q-value <0.001) were used as input. The rows represent the tissue samples and the columns the CpG sites. Each sample is represented by a unique code, which consist of the patient ID (1 to 20) followed by the letter B (benign prostate tissue) or C (PCa tissue). Methylation M-values were used to construct the heat map. B, characteristics of patients in the study. The corresponding patient IDs are shown in the heat map. Abbreviations: PSA, prostate-specific antigen; EA, European-American; AA, African-American.

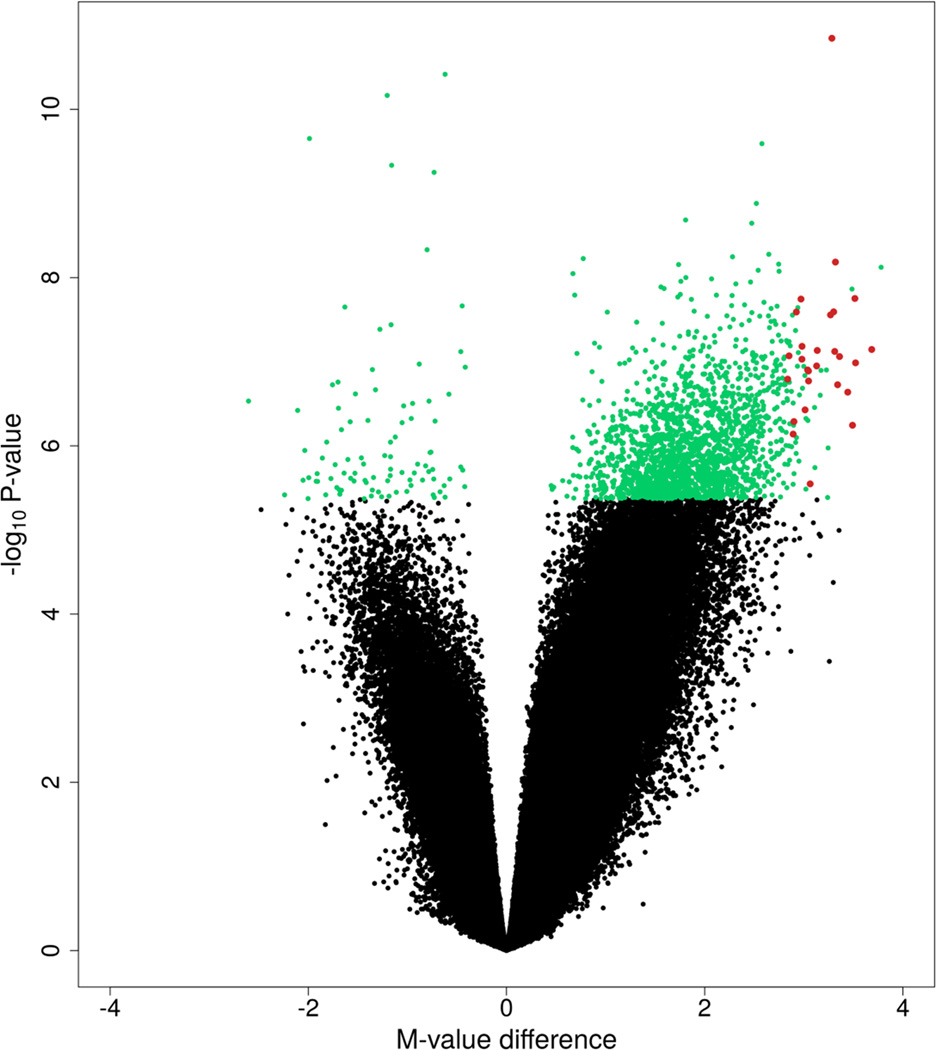

There were 27 top-ranked differentially methylated CpGs that had a mean methylation difference of at least 40% between PCa versus adjacent benign tissue (Figure 3; Table 2). These 27 CpGs were all hypermethylated. While 25 of the CpGs were in genes (No. of genes = 17), two were intergenic. One of the CpGs was in a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) locus (minor allele frequency ≥5%), which was the CpG in the HLA-J gene, and this finding therefore needs to be interpreted with caution. No hypomethylated CpGs were identified when using these same criteria. For comparison, the 27 CpGs were investigated in the PCa and adjacent benign tissue dataset from TCGA. All CpGs were significantly hypermethylated in PCa in TCGA (all P-values ≤8.80E-11), with mean methylation differences in cancer versus benign tissue ranging from 26% to 53% (mean = 40%).

Figure 3.

Volcano plot of DNA methylation in PCa versus adjacent benign tissue. Differentially methylated CpGs (Q <0.001; n = 2,040) are labelled in green or red. The 27 red-labelled CpG sites had a mean methylation difference of at least 40% between cancer and benign tissue and were all hypermethylated.

Table 2.

Top-ranked differentially methylated CpGs in prostate cancer versus adjacent benign tissuea

| CpG ID | Chromosome | Gene | Location | CpG island | Mean β cancer |

Mean β benign |

Mean β difference |

Q-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cg26027669 | 1 | GFI1 | TSS1500 | Yes | 0.61 | 0.16 | 0.45 | 6.84E-06 |

| cg18755783 | 13 | SPG20 | 5'UTR | Yes | 0.64 | 0.20 | 0.43 | 1.97E-04 |

| cg07016276 | 6 | HLA-F | Body | Yes | 0.62 | 0.19 | 0.43 | 2.35E-04 |

| cg01404317 | 13 | SPG20 | 5'UTR | Yes | 0.69 | 0.28 | 0.42 | 2.35E-04 |

| cg19548479 | 17 | TMEM106A | TSS200 | Yes | 0.67 | 0.22 | 0.44 | 2.47E-04 |

| cg15472092 | 7 | KCNH2 | TSS200 | Yes | 0.66 | 0.25 | 0.41 | 2.47E-04 |

| cg03049782 | 17 | TMEM106A | TSS200 | Yes | 0.64 | 0.21 | 0.43 | 2.47E-04 |

| cg24940138 | 17 | TMEM106A | TSS200 | Yes | 0.63 | 0.22 | 0.41 | 3.28E-04 |

| cg08193650 | 2 | ZFP36L2 | Body | Yes | 0.57 | 0.16 | 0.41 | 3.31E-04 |

| cg08952506 | 2 | AOX1 | TSS200 | Yes | 0.62 | 0.21 | 0.41 | 3.31E-04 |

| cg07564962 | 5 | – | – | Yes | 0.59 | 0.19 | 0.40 | 3.31E-04 |

| cg08879910 | 6 | HLA-J | Body | Yes | 0.72 | 0.32 | 0.40 | 3.36E-04 |

| cg14936968 | 3 | IL17RD | Body | Yes | 0.69 | 0.26 | 0.43 | 3.36E-04 |

| cg08498787 | 11 | – | – | Yes | 0.66 | 0.25 | 0.41 | 3.36E-04 |

| cg15026277 | 17 | TMEM106A | TSS200 | Yes | 0.60 | 0.18 | 0.43 | 3.36E-04 |

| cg07519235 | 16 | GPRC5B | 5'UTR | Yes | 0.75 | 0.32 | 0.43 | 3.36E-04 |

| cg26388816 | 12 | B4GALNT3 | Body | Yes | 0.70 | 0.28 | 0.42 | 3.41E-04 |

| cg24033558 | 15 | SHF | Body | Yes | 0.68 | 0.27 | 0.41 | 3.42E-04 |

| cg01030534 | 7 | FAM115A | 5'UTR | No | 0.72 | 0.32 | 0.41 | 3.52E-04 |

| cg18726691 | 15 | RHCG | Exon 1 | Yes | 0.71 | 0.29 | 0.42 | 3.65E-04 |

| cg21211480 | 17 | TMEM106A | TSS200 | Yes | 0.59 | 0.18 | 0.41 | 3.71E-04 |

| cg14142965 | 12 | TXNRD1 | TSS200 | Yes | 0.62 | 0.19 | 0.43 | 3.88E-04 |

| cg14117138 | 19 | HIF3A | TSS1500 | Yes | 0.72 | 0.31 | 0.41 | 4.34E-04 |

| cg03514404 | 7 | FAM115A | 5'UTR | No | 0.70 | 0.29 | 0.41 | 4.67E-04 |

| cg02636041 | 10 | RASGEF1A | Body | Yes | 0.76 | 0.30 | 0.46 | 4.86E-04 |

| cg02245020 | 7 | FAM115A | 5'UTR | No | 0.69 | 0.28 | 0.40 | 5.28E-04 |

| cg16876647 | 2 | ZFP36L2 | Body | Yes | 0.62 | 0.22 | 0.40 | 8.57E-04 |

Abbreviations: TSS1500, 200 to 1500 base pairs upstream of the transcription start site; TSS200, 200 base pairs upstream of the transcription start site; UTR, untranslated region

The table shows differentially methylated CpGs (FDR Q-value <0.001) in PCa versus adjacent benign tissue that have a mean methylation (β-value) difference of at least 40%. All CpGs were hypermethylated in PCa; no hypomethylated CpGs were identified using the same selection criteria.

We then investigated whether the methylation results for the 27 top-ranked CpGs were different in subgroups of patients with high (≥7) versus low (≤6) Gleason grade tumors. Although the numbers of men in these subgroups were limited, the results were similar.

The next analysis focused on DNA methylation in gene promoter regions. For ten genes over 50% of promoter region CpGs were hypermethylated (Q-value <0.001; Table 3). For these genes, the average methylation difference across all promoter region CpGs between cancer and benign tissue was calculated; average promoter region methylation differences ranged from 21% to 39% (mean = 27%). Three genes identified using this approach also contained one or more of the 27 top-ranked CpGs in Table 2: TMEM106A, AOX1, and RHCG. The same approach was used to examine the ten genes in the TCGA dataset, which showed similar results. All ten genes in Table 3 demonstrated promoter hypermethylation in TCGA with average methylation differences (cancer vs. benign) ranging from 21% to 36% (mean = 30%). No genes had more than 50% hypomethylated promoter region CpGs in our study, and the gene with the highest percentage of hypomethylated CpGs in cancer versus benign tissue was MC5R (33%).

Table 3.

Genes with promoter region DNA hypermethylation in prostate cancer compared to adjacent benign tissuea

| Gene | Hypermethylated promoter CpGsb |

Evaluated promoter CpGsb |

Proportion of hypermethylated CpGs in the promoter region |

Mean β difference of promoter CpGsc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HES5 | 6 (6) | 8 (6) | 0.75 | 0.26 |

| TMEM106A | 6 (6) | 8 (8) | 0.75 | 0.39 |

| LOC145663 | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | 0.67 | 0.28 |

| RHCG | 6 (6) | 9 (8) | 0.67 | 0.30 |

| AOX1 | 7 (6) | 11 (9) | 0.64 | 0.32 |

| TAC1 | 7 (6) | 11 (7) | 0.64 | 0.26 |

| OXGR1 | 8 (3) | 13 (3) | 0.62 | 0.23 |

| SALL2 | 3 | 5 | 0.60 | 0.22 |

| TRIP6 | 3 | 5 | 0.60 | 0.21 |

| SCGB3A1 | 4 (4) | 7 (7) | 0.57 | 0.25 |

The genes in the table have more than 50% hypermethylated promoter region CpGs (Q-value <0.001).

The number in parenthesis represents the number of promoter region CpGs that are in a CpG island.

The mean β-value difference was calculated over all CpGs in the promoter region of the gene.

Gene expression levels of the top-ranked differentially methylated genes were analyzed using the same matched tissue samples. To increase the likelihood of finding true positives, the analysis focused on the genes with hypermethylated CpGs shown in Tables 2 and 3. Of the 18 genes that had transcript data available, three genes had reduced mRNA expression (P-value <0.05) in PCa versus adjacent benign tissue: AOX1 (log2 fold change (FC) = −0.57; P-value = 0.011), HIF3A (two significant transcripts; transcript 1: log2 FC = −0.78, P-value = 0.014; transcript 2: log2 FC = −0.62, P-value = 0.033), and SCGB3A1 (log2 FC = −1.21, P-value = 0.0004). All three genes had hypermethylated promoter regions.

A secondary analysis focused on DMRs, which were identified using the Probe Lasso method. Twenty DMRs were identified (Q-value <0.001), and all were hypermethylated in PCa versus adjacent non-cancer tissue (Table 4). Seventeen of these regions were in genes, ten were in gene promoter regions, and three were intergenic. A number of the regions were in or near genes of the HLA gene family on chromosome6.

Table 4.

Differentially methylated regions in prostate cancer compared to adjacent benign tissuea

| DMR No. | Chromosome | Gene | DMR start (bp) | DMR end (bp) | DMR size (bp) | No. CpGsb | Mean β cancer |

Mean β benign |

Mean β difference |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 | HLA-J | 29974174 | 29975231 | 1058 | 35 | 0.55 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 1.11E-76 |

| 2 | 6 | – | 30094969 | 30095358 | 390 | 19 | 0.67 | 0.45 | 0.21 | 2.01E-33 |

| 3 | 6 | HLA-H | 29855329 | 29855567 | 239 | 9 (2) | 0.62 | 0.35 | 0.27 | 2.60E-20 |

| 4 | 6 | HLA-G | 29796293 | 29796516 | 224 | 11 | 0.51 | 0.34 | 0.17 | 9.36E-20 |

| 5 | 17 | SEPT9 | 75315256 | 75315897 | 642 | 8 (8) | 0.49 | 0.19 | 0.29 | 1.59E-19 |

| 6 | 3 | RARB | 25469684 | 25470221 | 538 | 9 (9) | 0.59 | 0.30 | 0.29 | 3.05E-19 |

| 7 | 6 | SLC44A4; NEU1 | 31831160 | 31831553 | 394 | 9 (8) | 0.51 | 0.23 | 0.29 | 1.41E-17 |

| 8 | 6 | IER3 | 30711510 | 30711712 | 203 | 8 | 0.61 | 0.32 | 0.29 | 1.54E-17 |

| 9 | 17 | RARA | 38465280 | 38465740 | 461 | 7 (7) | 0.57 | 0.30 | 0.27 | 1.51E-16 |

| 10 | 10 | PRAP1 | 135160660 | 135161434 | 775 | 8 (7) | 0.56 | 0.33 | 0.23 | 2.13E-16 |

| 11 | 11 | SHANK2 | 70672595 | 70672885 | 291 | 6 | 0.57 | 0.34 | 0.24 | 6.49E-14 |

| 12 | 6 | – | 44528201 | 44529749 | 1549 | 6 | 0.59 | 0.36 | 0.23 | 5.04E-13 |

| 13 | 20 | LOC284798 | 25129479 | 25129570 | 92 | 5 (5) | 0.50 | 0.23 | 0.27 | 1.96E-12 |

| 14 | 2 | CLIP4 | 29338072 | 29338128 | 57 | 5 (5) | 0.56 | 0.24 | 0.32 | 2.08E-12 |

| 15 | 6 | HCG4 | 29759872 | 29760100 | 229 | 7 | 0.47 | 0.29 | 0.18 | 3.03E-12 |

| 16 | 2 | – | 123418130 | 123419685 | 1556 | 5 | 0.64 | 0.35 | 0.29 | 4.80E-12 |

| 17 | 11 | DGKZ | 46382644 | 46383528 | 885 | 5 (1) | 0.57 | 0.31 | 0.26 | 5.04E-12 |

| 18 | 22 | NFAM1 | 42827738 | 42828512 | 775 | 6 (5) | 0.66 | 0.42 | 0.24 | 5.28E-12 |

| 19 | 2 | NRXN1 | 50574924 | 50575243 | 320 | 5 | 0.44 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 6.93E-09 |

| 20 | 6 | HLA-E | 30458022 | 30458224 | 203 | 10 | 0.39 | 0.26 | 0.13 | 1.66E-05 |

Abbreviations: DMR, differentially methylated region; bp, base pairs

All significant DMRs (Q-value <0.001) were hypermethylated in PCa, and no hypomethylated regions were identified.

The number in parenthesis is the number of promoter region CpGs.

DISCUSSION

This study investigated epigenome-wide DNA methylation in paired PCa versus adjacent histologically benign tissue samples from 20 patients with clinically localized disease. Many differentially methylated CpGs and regions, the majority of which were hypermethylated, were found in both gene promoter and non-promoter regions (e.g., gene body and intergenic regions), and for some of the genes promoter hypermethylation correlated with reduced mRNA expression. Some previously reported associations between PCa and aberrantly methylated gene promoter regions were confirmed in our dataset. Analysis of TCGA data provided confirmatory evidence for our findings.

The present study showed promoter region hypermethylation of AOX1. At least four previous studies showed that the promoter region of this gene is hypermethylated in PCa (11,16,28,29). One of these prior studies used the HM450 platform for methylation profiling of 19 PCa and four adjacent benign samples (11). Similar to our study, these investigators reported that most AOX1 promoter region CpG sites were strongly hypermethylated in PCa, with a corresponding reduction in AOX1 mRNA expression. AOX1 encodes an oxidase that metabolizes xenobiotics (30). Taken together these results suggest that aberrant promoter methylation may lead to silencing of AOX1 and thereby contributes to the development of PCa. The relatively large differences observed in promoter region methylation levels between PCa and adjacent benign tissue suggest that AOX1 promoter hypermethylation may be a useful biomarker for PCa diagnosis.

A few of the other top-ranked hypermethylated genes identified in the present study have previously been found to be hypermethylated in PCa, including HIF3A (16), RHCG (16,29), TMEM106A (29), TAC1 (29), and HES5 (31). In the present study, promoter hypermethylation of HIF3A (hypoxia inducible factor 3, alpha subunit) also correlated with lower mRNA expression levels. The other top-ranked methylated genes are involved in different biological processes (e.g., transcriptional repression [GFI1] (32), immune responses [HLA-F] (33)), but evidence from previous studies that these genes play a role in PCa is limited. Promoter region hypermethylation of TAC1 (tachykinin, precursor 1) has previously been associated with a number of other cancers including colorectal and lung cancers (34,35).

The present study also showed gene promoter hypermethylation of SCGB3A1 (HIN1) in PCa, which correlated with lower mRNA expression. SCGB3A1 is part of the secretoglobin family and is suggested to function as a tumor-suppressor (36). Many studies have reported that aberrant promoter methylation of SCGB3A1 is associated with breast cancer (37), and there is some evidence from candidate gene and laboratory studies for a role in other cancers including PCa (36,38–40). Our study is the first epigenome-wide analysis to show that promoter region hypermethylation of SCGB3A1 is associated with PCa, and that such aberrant methylation may repress gene transcription levels.

In a secondary analysis we searched for differentially methylated regions (DMRs) and identified 20 hypermethylated regions that included not only gene promoters but also gene body and intergenic regions. Interestingly, the analyses showed five relatively large regions in the gene body of five genes of the Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) gene family: HLA-J, HLA-H, HLA-G, HCG4, and HLA-E, located on chromosome 6 (33). In addition, there were four other DMRs on chromosome six, some of which were near the HLA gene family. These results are consistent with the notion that the immune system plays a role in PCa (41), and that effects may be mediated through alterations in DNA methylation.

Furthermore, the DMR analysis showed a hypermethylated region in the promoter of RARB. The region included nine CpGs that were near the transcription start site (TSS200 and 5’UTR) but the region did not include promoter CpGs that were further upstream of the transcription start site (TSS1500). RARB is a tumor-suppressor gene and many studies have shown that promoter hypermethylation of RARB is a common event in PCa (42,43). The other top-ranked regions included different genes, but evidence from previous studies that methylation in these genes contributes to cancer is limited. One exception however is SEPT9, which has been shown to be hypermethylated in colorectal cancer, and there is a diagnostic test for colorectal cancer that measures SEPT9 methylation (44–46). Our study provides novel evidence that SEPT9 promoter hypermethylation may also contribute to PCa.

The most thoroughly studied differentially methylated gene in PCa is GSTP1 (glutathione S-transferase Pi 1) (7). Many studies have reported that CpG island promoter hypermethylation of this gene is a frequent event in PCa, and GSTP1 is one of three genes included in a methylation-based diagnostic test for PCa (8,47,48). In this study, five out of 19 evaluated CpGs in GSTP1 were hypermethylated, including three promoter region CpGs close to the transcription start site (TSS200 and exon 1). Promoter CpGs further upstream of the transcription start site (TSS1500) were not differentially methylated, which is confirmed by previous epigenome-wide studies of PCa (11,13). The five significantly differentially methylated CpGs were in a CpG island, and we confirmed in our dataset that mRNA expression of GSTP1 was significantly reduced in PCa versus adjacent benign tissue. In addition to GSTP1, however, our study provides compelling evidence that aberrant methylation in other genes may be more strongly associated with PCa suggesting that these genes may be useful for the development of future methylation-based diagnostic tests or as potential therapeutic targets.

Strengths of this study include the epigenome-wide approach to investigate CpG methylation and the paired (cancer–benign) study design. Study participants had clinical and pathological characteristics that were typical for the larger population-based patient cohort from which this subset of patients was derived. Furthermore, we confirmed associations for our top-ranked differentially methylated CpGs in the TCGA dataset. A limitation of the study is the sample size, but our study is larger than the two previous studies of PCa and adjacent benign tissue that used the HM450 array to interrogate epigenome-wide differentially methylated CpGs (9,11).

In conclusion, this epigenomic study of DNA methylation in PCa versus adjacent benign tissue identified many differentially methylated CpGs and regions, some of which involved genes that have not been previously implicated as playing a role in PCa development or progression. The study also replicated earlier reports of associations between PCa and a few aberrantly methylated genes and highlighted three top-ranked genes with hypermethylated CpG sites in the promoter region that also had reduced mRNA expression levels. Further research is needed to confirm these results and to investigate the potential clinical utility of the findings in relation to the diagnosis and treatment of PCa.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Beatrice Knudson and Antonio Hurado-Coll for their assistance with the pathology. We also thank the men who participated in the study.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA056678, R01 CA092579, and P50 CA097186), with additional support provided by the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and the Prostate Cancer Foundation. Milan Geybels is the recipient of a Dutch Cancer Society Fellowship (BUIT 2014–6645).

REFERENCES

- 1.Herman JG, Baylin SB. Gene silencing in cancer in association with promoter hypermethylation. The New England journal of medicine. 2003;349(21):2042–2054. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra023075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones PA, Baylin SB. The epigenomics of cancer. Cell. 2007;128(4):683–692. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeronimo C, Bastian PJ, Bjartell A, Carbone GM, Catto JW, Clark SJ, Henrique R, Nelson WG, Shariat SF. Epigenetics in prostate cancer: biologic and clinical relevance. European urology. 2011;60(4):753–766. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lou S, Lee HM, Qin H, Li JW, Gao Z, Liu X, Chan LL, Kl Lam V, So WY, Wang Y, Lok S, Wang J, Ma RC, Tsui SK, Chan JC, Chan TF, Yip KY. Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing of multiple individuals reveals complementary roles of promoter and gene body methylation in transcriptional regulation. Genome biology. 2014;15(7):408. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0408-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang X, Han H, De Carvalho DD, Lay FD, Jones PA, Liang G. Gene body methylation can alter gene expression and is a therapeutic target in cancer. Cancer cell. 2014;26(4):577–590. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKee TC, Tricoli JV. Epigenetics of prostate cancer. Methods in molecular biology. 2015;1238:217–234. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-1804-1_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Neste L, Herman JG, Otto G, Bigley JW, Epstein JI, Van Criekinge W. The epigenetic promise for prostate cancer diagnosis. The Prostate. 2012;72(11):1248–1261. doi: 10.1002/pros.22459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Partin AW, Van Neste L, Klein EA, Marks LS, Gee JR, Troyer DA, Rieger-Christ K, Jones JS, Magi-Galluzzi C, Mangold LA, Trock BJ, Lance RS, Bigley JW, Van Criekinge W, Epstein JI. Clinical validation of an epigenetic assay to predict negative histopathological results in repeat prostate biopsies. The Journal of urology. 2014;192(4):1081–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devaney JM, Wang S, Funda S, Long J, Taghipour DJ, Tbaishat R, Furbert-Harris P, Ittmann M, Kwabi-Addo B. Identification of novel DNA-methylated genes that correlate with human prostate cancer and high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Prostate cancer and prostatic diseases. 2013;16(4):292–300. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2013.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim JH, Dhanasekaran SM, Prensner JR, Cao X, Robinson D, Kalyana-Sundaram S, Huang C, Shankar S, Jing X, Iyer M, Hu M, Sam L, Grasso C, Maher CA, Palanisamy N, Mehra R, Kominsky HD, Siddiqui J, Yu J, Qin ZS, Chinnaiyan AM. Deep sequencing reveals distinct patterns of DNA methylation in prostate cancer. Genome research. 2011;21(7):1028–1041. doi: 10.1101/gr.119347.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim JW, Kim ST, Turner AR, Young T, Smith S, Liu W, Lindberg J, Egevad L, Gronberg H, Isaacs WB, Xu J. Identification of new differentially methylated genes that have potential functional consequences in prostate cancer. PloS one. 2012;7(10):e48455. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim SJ, Kelly WK, Fu A, Haines K, Hoffman A, Zheng T, Zhu Y. Genome-wide methylation analysis identifies involvement of TNF-alpha mediated cancer pathways in prostate cancer. Cancer letters. 2011;302(1):47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kobayashi Y, Absher DM, Gulzar ZG, Young SR, McKenney JK, Peehl DM, Brooks JD, Myers RM, Sherlock G. DNA methylation profiling reveals novel biomarkers and important roles for DNA methyltransferases in prostate cancer. Genome research. 2011;21(7):1017–1027. doi: 10.1101/gr.119487.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kron K, Pethe V, Briollais L, Sadikovic B, Ozcelik H, Sunderji A, Venkateswaran V, Pinthus J, Fleshner N, van der Kwast T, Bapat B. Discovery of novel hypermethylated genes in prostate cancer using genomic CpG island microarrays. PloS one. 2009;4(3):e4830. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luo JH, Ding Y, Chen R, Michalopoulos G, Nelson J, Tseng G, Yu YP. Genome-wide methylation analysis of prostate tissues reveals global methylation patterns of prostate cancer. The American journal of pathology. 2013;182(6):2028–2036. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahapatra S, Klee EW, Young CY, Sun Z, Jimenez RE, Klee GG, Tindall DJ, Donkena KV. Global methylation profiling for risk prediction of prostate cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2012;18(10):2882–2895. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agalliu I, Salinas CA, Hansten PD, Ostrander EA, Stanford JL. Statin use and risk of prostate cancer: results from a population-based epidemiologic study. American journal of epidemiology. 2008;168(3):250–260. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stanford JL, Wicklund KG, McKnight B, Daling JR, Brawer MK. Vasectomy and risk of prostate cancer. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 1999;8(10):881–886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stott-Miller M, Zhao S, Wright JL, Kolb S, Bibikova M, Klotzle B, Ostrander EA, Fan JB, Feng Z, Stanford JL. Validation study of genes with hypermethylated promoter regions associated with prostate cancer recurrence. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2014;23(7):1331–1339. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aryee MJ, Jaffe AE, Corrada-Bravo H, Ladd-Acosta C, Feinberg AP, Hansen KD, Irizarry RA. Minfi: a flexible and comprehensive Bioconductor package for the analysis of Infinium DNA methylation microarrays. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(10):1363–1369. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maksimovic J, Gordon L, Oshlack A. SWAN: Subset-quantile within array normalization for illumina infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChips. Genome biology. 2012;13(6):R44. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-6-r44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson WE, Li C, Rabinovic A. Adjusting batch effects in microarray expression data using empirical Bayes methods. Biostatistics. 2007;8(1):118–127. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxj037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Du P, Zhang X, Huang CC, Jafari N, Kibbe WA, Hou L, Lin SM. Comparison of Beta-value and M-value methods for quantifying methylation levels by microarray analysis. BMC bioinformatics. 2010;11:587. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, Smyth GK. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic acids research. :2015. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Storey JD, Tibshirani R. Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(16):9440–9445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1530509100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hansen K. R package version 0.2.1. IlluminaHumanMethylation450kanno.ilmn12.hg19: Annotation for Illumina's 450k methylation arrays. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Butcher LM, Beck S. Probe Lasso: a novel method to rope in differentially methylated regions with 450K DNA methylation data. Methods. 2015;72:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2014.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haldrup C, Mundbjerg K, Vestergaard EM, Lamy P, Wild P, Schulz WA, Arsov C, Visakorpi T, Borre M, Hoyer S, Orntoft TF, Sorensen KD. DNA methylation signatures for prediction of biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy of clinically localized prostate cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31(26):3250–3258. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Borno ST, Fischer A, Kerick M, Falth M, Laible M, Brase JC, Kuner R, Dahl A, Grimm C, Sayanjali B, Isau M, Rohr C, Wunderlich A, Timmermann B, Claus R, Plass C, Graefen M, Simon R, Demichelis F, Rubin MA, Sauter G, Schlomm T, Sultmann H, Lehrach H, Schweiger MR. Genome-wide DNA methylation events in TMPRSS2-ERG fusion-negative prostate cancers implicate an EZH2-dependent mechanism with miR-26a hypermethylation. Cancer discovery. 2012;2(11):1024–1035. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garattini E, Terao M. The role of aldehyde oxidase in drug metabolism. Expert opinion on drug metabolism & toxicology. 2012;8(4):487–503. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2012.663352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Massie CE, Spiteri I, Ross-Adams H, Luxton H, Kay J, Whitaker HC, Dunning MJ, Lamb AD, Ramos-Montoya A, Brewer DS, Cooper CS, Eeles R, Group UKPI, Warren AY, Tavare S, Neal DE, Lynch AG. HES5 silencing is an early and recurrent change in prostate tumourigenesis. Endocrine-related cancer. 2015;22(2):131–144. doi: 10.1530/ERC-14-0454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van der Meer LT, Jansen JH, van der Reijden BA. Gfi1 and Gfi1b: key regulators of hematopoiesis. Leukemia. 2010;24(11):1834–1843. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adams EJ, Luoma AM. The adaptable major histocompatibility complex (MHC) fold: structure and function of nonclassical and MHC class I-like molecules. Annual review of immunology. 2013;31:529–561. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-095912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tham C, Chew M, Soong R, Lim J, Ang M, Tang C, Zhao Y, Ong SY, Liu Y. Postoperative serum methylation levels of TAC1 and SEPT9 are independent predictors of recurrence and survival of patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2014;120(20):3131–3141. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wrangle J, Machida EO, Danilova L, Hulbert A, Franco N, Zhang W, Glockner SC, Tessema M, Van Neste L, Easwaran H, Schuebel KE, Licchesi J, Hooker CM, Ahuja N, Amano J, Belinsky SA, Baylin SB, Herman JG, Brock MV. Functional identification of cancer-specific methylation of CDO1, HOXA9, and TAC1 for the diagnosis of lung cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2014;20(7):1856–1864. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krop I, Player A, Tablante A, Taylor-Parker M, Lahti-Domenici J, Fukuoka J, Batra SK, Papadopoulos N, Richards WG, Sugarbaker DJ, Wright RL, Shim J, Stamey TA, Sellers WR, Loda M, Meyerson M, Hruban R, Jen J, Polyak K. Frequent HIN-1 promoter methylation and lack of expression in multiple human tumor types. Molecular cancer research : MCR. 2004;2(9):489–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dai D, Dong XH, Cheng ST, Zhu G, Guo XL. Aberrant promoter methylation of HIN-1 gene may contribute to the pathogenesis of breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Tumour biology : the journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine. 2014;35(8):8209–8216. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ho CM, Huang CJ, Huang CY, Wu YY, Chang SF, Cheng WF. Promoter methylation status of HIN-1 associated with outcomes of ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma. Molecular cancer. 2012;11:53. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-11-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shigematsu H, Suzuki M, Takahashi T, Miyajima K, Toyooka S, Shivapurkar N, Tomlinson GE, Mastrangelo D, Pass HI, Brambilla E, Sathyanarayana UG, Czerniak B, Fujisawa T, Shimizu N, Gazdar AF. Aberrant methylation of HIN-1 (high in normal-1) is a frequent event in many human malignancies. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2005;113(4):600–604. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu Y, Yin D, Hoque MO, Cao B, Jia Y, Yang Y, Guo M. AKT signaling pathway activated by HIN-1 methylation in non-small cell lung cancer. Tumour biology : the journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine. 2012;33(2):307–314. doi: 10.1007/s13277-011-0266-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Marzo AM, Platz EA, Sutcliffe S, Xu J, Gronberg H, Drake CG, Nakai Y, Isaacs WB, Nelson WG. Inflammation in prostate carcinogenesis. Nature reviews Cancer. 2007;7(4):256–269. doi: 10.1038/nrc2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao T, He B, Pan Y, Li R, Xu Y, Chen L, Nie Z, Gu L, Wang S. The association of retinoic acid receptor beta2(RARbeta2) methylation status and prostate cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one. 2013;8(5):e62950. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jeronimo C, Henrique R, Hoque MO, Ribeiro FR, Oliveira J, Fonseca D, Teixeira MR, Lopes C, Sidransky D. Quantitative RARbeta2 hypermethylation: a promising prostate cancer marker. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2004;10(12 Pt 1):4010–4014. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Church TR, Wandell M, Lofton-Day C, Mongin SJ, Burger M, Payne SR, Castanos-Velez E, Blumenstein BA, Rosch T, Osborn N, Snover D, Day RW, Ransohoff DF, Steering PCS. Prospective evaluation of methylated SEPT9 in plasma for detection of asymptomatic colorectal cancer. Gut. 2014;63(2):317–325. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li Y, Song L, Gong Y, He B. Detection of colorectal cancer by DNA methylation biomarker SEPT9: past, present and future. Biomarkers in medicine. 2014;8(5):755–769. doi: 10.2217/bmm.14.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gyparaki MT, Basdra EK, Papavassiliou AG. DNA methylation biomarkers as diagnostic and prognostic tools in colorectal cancer. Journal of molecular medicine. 2013;91(11):1249–1256. doi: 10.1007/s00109-013-1088-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meiers I, Shanks JH, Bostwick DG. Glutathione S-transferase pi (GSTP1) hypermethylation in prostate cancer: review 2007. Pathology. 2007;39(3):299–304. doi: 10.1080/00313020701329906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Millar DS, Ow KK, Paul CL, Russell PJ, Molloy PL, Clark SJ. Detailed methylation analysis of the glutathione S-transferase pi (GSTP1) gene in prostate cancer. Oncogene. 1999;18(6):1313–1324. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]