A novel optogenetics platform based on microscopic arrays of organic LEDs is used to control cells with light.

Keywords: OLED, optogenetics, microdisplay, organic electronics, neuroscience, channelrhodopsin

Abstract

Optogenetics is a paradigm-changing new method to study and manipulate the behavior of cells with light. Following major advances of the used genetic constructs over the last decade, the light sources required for optogenetic control are now receiving increased attention. We report a novel optogenetic illumination platform based on high-density arrays of microscopic organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs). Because of the small dimensions of each array element (6 × 9 μm2) and the use of ultrathin device encapsulation, these arrays enable illumination of cells with unprecedented spatiotemporal resolution. We show that adherent eukaryotic cells readily proliferate on these arrays, and we demonstrate specific light-induced control of the ionic current across the membrane of individual live cells expressing different optogenetic constructs. Our work paves the way for the use of OLEDs for cell-specific optogenetic control in cultured neuronal networks and for acute brain slices, or as implants in vivo.

INTRODUCTION

Optogenetics is an emerging technology based on introducing transgenes that code for light-sensitive proteins into cells, and then using light to control cellular behavior (1, 2). These light-sensitive proteins typically contain or host a chromophore that changes conformation when absorbing light of a certain wavelength. Depending on the function of the light-activated protein, this enables manipulation of cell migration, metabolism, or electrical activity. Optogenetics has been particularly successful in neuroscience, where light-activated ion-channel proteins are now widely used to control the behavior of neuronal cells.

In addition to appropriate gene constructs, precise optogenetic control of cells requires light sources that are spectrally matched to the activation spectrum of the protein of interest and that provide appropriate temporal and spatial control. So far, most optogenetic experiments have used standard arc lamps (3, 4), lasers (5), or light-emitting diodes (LEDs) (6, 7). For cells in culture, light is typically delivered through a microscope, whereas in vivo experiments use optical fibers to deliver light to the target cells (8, 9). For multiple-site stimulation, multiple-point emitting optical fibers have been used (10). Other developments are based on optrodes (hybrids of light sources and electrophysiological recording electrodes) (11) and arrays of μLEDs (12–15). Although these developments are very promising, the spatial resolution of the currently pursued approaches remains limited to dimensions larger than the size of typical cells, and it is unclear whether true cellular or subcellular resolution can be achieved with existing technology. In addition, so far, the number of illumination spots that can be controlled independently is limited.

A potential alternative light source is the organic LED (OLED), a novel type of LED based on π-conjugated, “plastic-type” organic materials. Although most current research on OLEDs is aimed at information displays and solid-state illumination (16–18), OLEDs offer a range of highly attractive characteristics for applications in biotechnology and biomedicine. These include simple spectral tuning (19, 20), mechanical flexibility and low weight (21, 22), sub-microsecond switching, high brightness, low heating, homogeneous emission, low toxicity, and—most importantly in the context of optogenetics—the potential to provide extremely high spatial resolution (23, 24). However, bringing OLEDs into contact with an aqueous biological environment requires highly efficient device encapsulation because exposure of the organic materials to as little as a few milligrams of water per square meter of device area leads to catastrophic device failure (25). Device encapsulation is typically achieved by laminating the OLED between sheets of glass (typical thickness, >100 μm). In this fully enclosed format, OLEDs have been used successfully as light sources for biomedical (26) and sensing (27–29) applications. However, because of divergence of light, even a micrometer-sized OLED would illuminate a millimeter-scale area at the surface of the encapsulation glass. To date, this issue has prevented researchers from harnessing the high-resolution advantage of OLEDs for lens-free delivery of light to individual cells.

Here, we demonstrate that arrays of microscopic OLEDs can be used as an optogenetic platform to specifically activate the light-sensitive ion channels of individual cells in real time. Using high-performance thin-film encapsulation (30, 31), we succeeded in culturing eukaryotic cells within less than 2 μm from these arrays without loss of cell viability or damage to the OLED array. The OLEDs allow for lens-free illumination of the individual cells with much higher spatial resolution than existing methods. The light intensity provided by the OLED arrays is sufficient to specifically stimulate electrical activity in light-sensitive, genetically modified human embryonic kidney (HEK)–293 cells, and the achievable shifts in membrane potential are compatible with the levels required to induce action potential firing in neuronal cells.

RESULTS

Structure, optical power, and stability of OLED microarrays

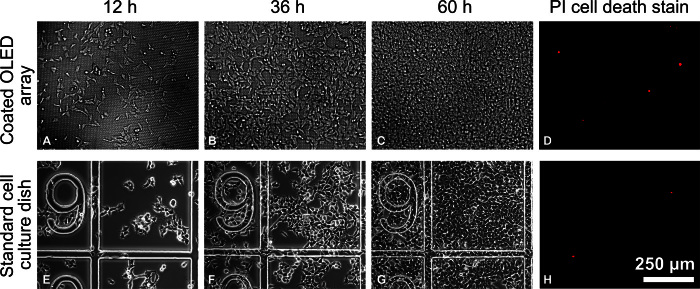

Figure 1A shows a schematic illustration of the OLED array with a blue-emitting fluorescent p-i-n (p-type, intrinsic, n-type) OLED stack deposited directly on top of a CMOS (complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor) backplane circuit and covered with a common cathode. Aluminum anode pads with a pitch smaller than a typical adhered cell (area, 6 × 9 μm2) are integrated with the backplane to define the OLED pixels. In total, the arrays comprise 230,000 pixels across an area of ~20 mm2. The current for each pixel can be controlled in real time (up to 120 Hz) by the CMOS backplane. This allows switching each pixel on and off individually and thus generating dynamic patterns of light. In addition, the voltage supplied to the common cathode can be adjusted to change the overall optical power density provided by the OLED array, allowing optical power densities of up to 25 W m−2 (Fig. 1B, Materials and Methods).

Fig. 1. Illustration of optogenetic cell stimulation with OLED microarrays.

(A) Schematic of OLED microarray with cells adhered on top of the array (not drawn to scale). The microarray is connected to a high-definition multimedia interface (HDMI) driver with a flexible connector. Each pixel of the array can be turned on and off by the driver and the CMOS backplane, thus providing controlled light exposure of individual cells. Light-induced changes in cell membrane current are measured with a patch clamp electrode (voltage clamp mode, whole-cell configuration). The cross section on the right shows the layer structure of the OLED array. (B) Optical power density at the surface of the OLED microarray versus applied cathode voltage. (C) Picture of the experimental setup with an upright microscope equipped with water immersion objective used to direct positioning of the patch electrode housed in a glass pipette. The microarray and the ground electrode are placed in a petri dish filled with salt solution. The flexible connector links the array to the driver located outside the field of view. A flow system constantly renews the salt solution.

To harness the high resolution of the OLED microarrays and the unrestricted simultaneous switching of pixels for pattern generation, cells have to be in close proximity to the OLEDs; ideally, the separation is less than the pixel size. To enable close contact while still protecting the water-sensitive OLED materials from the aqueous cell culture environment, OLED arrays were protected by a thin-film encapsulation barrier consisting of alternating layers of Al2O3 and an organic Barix polymer (three layers of Al2O3 and two layers of polymer; total thickness, 1.5 μm; Vitex Systems) (31). This barrier system achieves water transition rates as low as 10−6 g m−2 day−1, and we have previously found that OLEDs protected in this way can be fully immersed into a salt buffer solution for 72 hours without compromising device performance (32). As discussed below, the barrier also provides sufficient protection to allow adhesion of cells to the barrier surface without damaging the OLEDs underneath.

Adherence and viability of HEK-293 cells on OLED microarrays

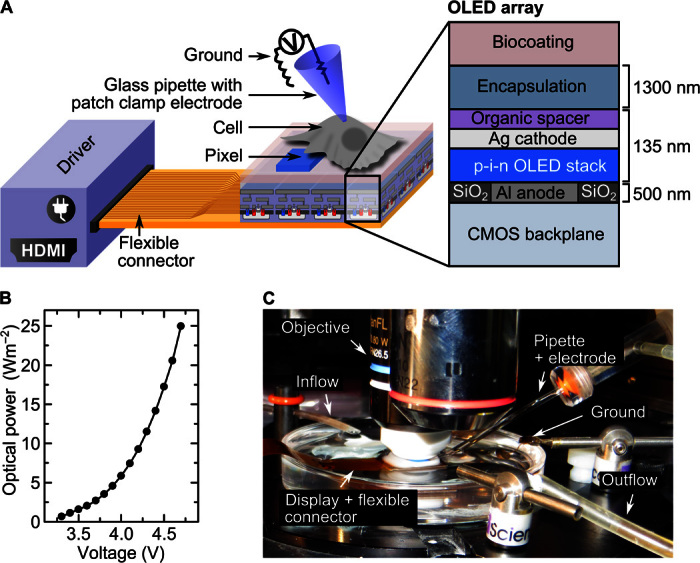

Good adherence and viability of cells on a given substrate are essential for long-term investigations of cell behavior. To promote cell adherence, we coated the thin-film encapsulation covering the OLED array with a thin layer of poly-l-lysine and a thin layer of the extracellular matrix protein fibronectin. When following this procedure, HEK-293 cells readily attached and proliferated on the array (Fig. 2). The morphology of cells on the OLED arrays was very similar to the morphology of control cells on a standard culture dish (see 12 hours in Fig. 2). Within 60 hours of seeding, cells proliferated to confluence on both the OLED array and the culture dish, confirming that growth rates and cell viability are not affected by using the OLED array as substrate. Propidium iodide staining was performed 60 hours after cell seeding and showed that the fraction of dead cells on the OLED arrays was negligible (Fig. 2, D and H), again confirming the absence of any cytotoxic effect.

Fig. 2. Viability of HEK-293 cells on OLED microarrays.

(A to C) Microscopic images (epi-illumination) of wild-type HEK-293 cells (HEK-293wt) adhered on poly-l-lysine/fibronectin–coated OLED microarray surface at 12, 36, and 60 hours after cell seeding. (E to G) Microscopic images (phase contrast) of HEK-293wt cells adhered to standard cell culture dishes (with grid) at 12, 36, and 60 hours after cell seeding. Cell density at seeding was equal for the OLED array and culture dish. (D and H) Epifluorescence images of propidium iodide (PI) cell death staining performed after 60 hours of culture on OLED arrays and standard culture dishes, respectively.

Optogenetic stimulation of HEK-293 cells with OLED microarrays

We tested the suitability of our OLED array for optogenetic activation with HEK-293 cells that were genetically modified to produce a photoswitchable channelrhodopsin-2 ion channel (ChR2). Photoswitching of ChR2s is based on an all-trans-retinal chromophore that is bound to the protein. Upon exposure to blue light, the retinal chromophore changes to the 13-cis conformation, which causes the ion channel to open. The resulting influx of positively charged ions (Ca2+, Na+, H+) into the cell then shifts the membrane potential from its resting state (typically between −40 and −80 mV in eukaryotic cells) in a positive direction. In neurons and other cells expressing voltage-gated ion channels, this shift triggers a further rapid change of membrane potential (known as spiking or “firing” in neurons) if the initial light-induced shift has taken the membrane potential above a critical threshold level.

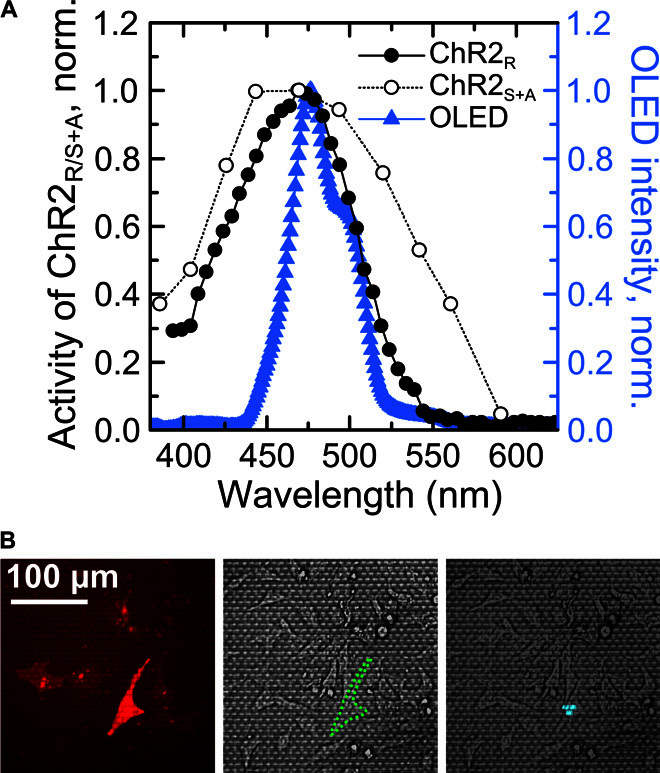

We tested two mutants of ChR2 with different channel activation and deactivation kinetics: ChR2-H134R-EYFP (enhanced yellow fluorescent protein) shows fast switching behavior (1 ms for activation and 21 ms for deactivation) (33); by contrast, ChR2-C128S/D156A-mCherry is a double mutant of the wild-type ChR2 and shows bistable switching characteristics, that is, once activated with light, the ion channel remains open in the dark (deactivation time constant, 29 min) and can be closed again by exposure to green or red light (8). Both ChR2s are most effectively opened by light of around 470-nm wavelength. The emission spectrum of the OLEDs used here was tuned to match the spectral response of the ChR2s (peak wavelength, 477 nm; full width at half maximum, 44 nm; Fig. 3A). Both channel proteins are tagged with a fluorescent protein marker (EYFP and mCherry, respectively) to visualize their expression level and location within cells.

Fig. 3. Spectral characteristics of OLED arrays and identification of light-sensitive HEK-293 cells.

(A) Left axis: Activity spectrum of the channelrhodopsin-2-H134R mutant (ChR2R, full circles) and channelrhodopsin-2-C128S/D156A mutant (ChR2S+A, open circles) (8). Right axis: Emission spectrum of blue OLED microarray (blue triangles). Lines serve as a guide to the eye. (B) Cells expressing ChR are identified through the fluorescent protein tag fused to the ion channel. Left: Epifluorescence microscopy image of a cell expressing ChR2S+A-mCherry. Middle: Reflected light microscopic image showing the same field of view as on the left; outline of target cell marked by green dashed line. Right: Overlay of reflected light microscopic image and image of the blue emission from the OLED array. Three pixels are switched on underneath the target cell to stimulate the ChR2S+A ion channels in the cell membrane.

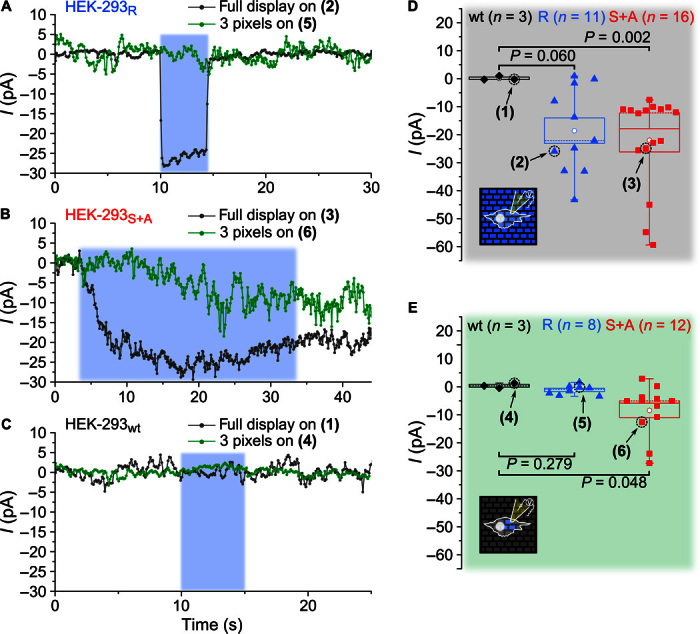

To investigate whether illumination by the OLED microarrays can open a significant number of ChR2s, we integrated the OLED arrays with a patch clamp setup (Fig. 1, A and C). ChR2-expressing HEK cells were identified on the OLED array by live-cell fluorescence imaging of their fluorescent protein tag (Fig. 3B, left); whole-cell patch clamp recordings were obtained using a fine-glass capillary electrode. The current across the cell membrane was continuously monitored in voltage clamp mode while cells were stimulated with blue light from the OLED array (Fig. 3B, right). Upon stimulation, the measured membrane current changed significantly, both for a cell expressing ChR2-H134R-EYFP (HEK-293R; Fig. 4A) and for a cell with ChR2-C128S/D156A-mCherry (HEK-293S+A; Fig. 4B), but did not change for a cell from a nontransfected control population (HEK-293wt; Fig. 4C). During illumination, the measured current in the ChR2-expressing cells was negative, consistent with the opening of ChR2s in the cell membrane and an associated influx of cations. The effect is most pronounced, if all pixels of the OLED array are switched on simultaneously. For the HEK-293S+A cell, we also measured a substantial current if only three pixels directly underneath the cell were turned on, whereas for the HEK-293R cell, no significant change in current was visible with this more limited stimulation.

Fig. 4. Specific optogenetic activation of ChR-expressing HEK-293 cells with OLED microarrays confirmed by whole-cell patch clamp measurements.

(A to C) Examples of patch clamp current (I) recordings for a HEK-293 cell expressing the ChR2-H134R ion channel (HEK-293R), a cell expressing the ChR2-C128S/D156A channel (HEK-293S+A), and a wild-type cell (HEK-293wt). Cells are stimulated by blue light from the OLEDs for a controlled period of time (blue-shaded area). Stimulation is applied by light either from all pixels of the array (dark gray traces) or from just three pixels directly underneath the target cell (green traces). (D and E) OLED-induced change in current for multiple cells (n, number of cells tested) with the full array on (D) and just three pixels on (E). The mean current change is indicated by a white circle, the SEM by the range of the box, the median by a dashed line, and the data range between minimum and maximum by the range of the whiskers. Numbers (1) to (6) indicate the measurements shown in (A) to (C). P values are according to Mann-Whitney U test.

To substantiate our finding, we repeated the above measurements for multiple cells. When all pixels on the OLED array were turned on, the mean current change (±SEM; see Materials and Methods) was −18.6 ± 4.6 pA for HEK-293R cells (n = 11) and −21.7 ± 4.0 pA for HEK293S+A cells (n = 16) (Fig. 4D). The HEK-293wt cells without light-sensitive ion channels did not show a significant change in current upon light exposure (0.1 ± 0.4 pA; n = 3). In addition to providing a control to confirm that the current change measured in HEK-293R and HEK293S+A was indeed induced by light from the OLEDs, this also shows that there were no adverse thermal effects due to OLED operation in direct vicinity of the cells. When repeating these current recordings with only three pixels turned on directly underneath the target cell (Fig. 4E), the mean change of inward current for HEK-293S+A cells was again significant (−8.4 ± 2.6 pA; n = 12) compared to the wild-type cells (0.4 ± 0.5 pA; n = 3). However, for the HEK-293R cells with the fast ChR2 mutant, no significant change in current was observed (−1.1 ± 0.6 pA; n = 8), suggesting that these cells were less light-sensitive than cells with the double mutant ChR2.

The bistable behavior of the double mutant ChR2 in HEK-293S+A cells can be clearly seen when comparing the HEK-293S+A recordings (Fig. 4B) to the HEK-293R recordings (Fig. 4A): For the former, the current remained at a negative value after turning the light off, whereas for the latter, it returned to zero within milliseconds. The HEK-293S+A cells thus effectively act as photon integrators (4); under continuous illumination, more and more ion channel proteins open, which leads to an asymptotic increase in the current across the membrane. By contrast, the HEK-293R cells quickly reach an equilibrium state in which the rate at which channels are opened by light exposure is equal to the rate of spontaneous channel closure. The higher light sensitivity of the HEK-293S+A cells compared to the HEK-293R cells is most likely associated with this difference in channel behavior.

The fact that a larger current is generally induced when activating all pixels on the OLED array instead of just three pixels underneath the investigated cell can be explained by considering that, for most cells, the illumination spot provided by the three pixels did not cover the full area of the cell. Scattering of light from regions of the OLED array that are far away from the cell may also contribute to the larger currents.

Spatial control of optogenetic stimulation of HEK-293 with OLED microarrays

To test whether OLED microarrays provide spatial control over cell activation, we next compared the photocurrents that are induced when pixels were turned on at different positions relative to a patched cell.

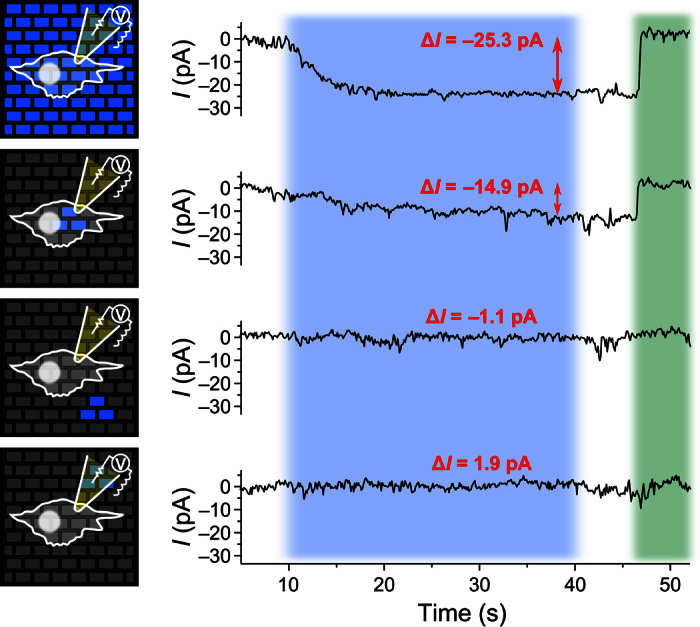

Figure 5 shows current recordings of a representative HEK-293S+A cell that was exposed to different illumination patterns. (After applying each of the illumination patterns, green epi-illumination through the microscope was used to homogeneously close the channels in all cells on the array and thus stop the ion current influx.) When the entire OLED array was turned on, the change in current was −25.3 pA. As before, for three pixels turned on underneath the cell, the induced current was somewhat smaller but still significant (−14.9 pA). When three pixels just next to the cell were switched on instead (distance of the center of the three pixels to the cell center, <30 μm), the current change was negligible (−1.1 pA). This confirms that, because of the close contact between cells and OLED pixels, there is no issue with divergence of light and, thus, only cells directly on top of active pixels are activated.

Fig. 5. Spatial resolution of the optogenetic activation achieved with OLED microarrays.

A HEK-293S+A cell attached to an OLED microarray is stimulated with different patterns of blue light from the array for 30 s (blue-shaded area) and subsequently deactivated with green light after switching off the OLED array (green-shaded area). The current (I) across the cell membrane is monitored using the whole-cell patch clamp recording technique during different stimulation patterns, as indicated by the schematic representations on the left. First row, full array switched on; second row, three pixels switched on underneath the cell; third row, three pixels switched on directly next to the cell but not underneath; and fourth row, three pixels switched on next to cell and underneath the patch pipette. The mean current change (ΔI) during light stimulation is indicated in red for each recording.

To rule out that the recorded signals are a measurement artifact, for example, from light-induced current in the patch clamp electrode itself, we also checked the response for three pixels underneath the electrode but not underneath the cell itself. Again, no significant change in current was observed (1.9 pA).

DISCUSSION

One of the main practical challenges to the commercialization of OLED technology has been the extreme sensitivity of the used materials to water and oxygen. This has necessitated intricate and often bulky device encapsulation strategies. However, we find that, by using state-of-the-art thin-film encapsulation, one can use OLEDs immersed in cell culture medium over the course of several days without losing device functionality. In the future, there may be interest in using OLED light sources in in vivo settings, for example, as implantable and flexible light sources for optogenetics or for biosensing; this may require further improvements in encapsulation performance. A particularly promising approach in this context is atomic layer deposition (ALD), a method for growing conformal and dense nanolaminates of oxides at temperatures <100°C (25). Using low-temperature ALD, water permeation rates down to 5 × 10−7 g m−2 day−1 have been demonstrated (34).

The OLED-induced membrane currents observed for HEK-293S+A cells in this work are in the range of −15 to −25 pA (depending on the area of illumination). Using Ohm’s law and the average resistance of the cell membrane (700 megohms in our case), these currents translate into increases in membrane potential of 10 to 20 mV. This is within the range of the depolarization required to evoke action potential firing in neuronal cells (typically 5 to 20 mV) (35, 36) and implies that, even in their present form, our OLED microarrays should be suitable to control activity in cultures of primary neurons. To use OLEDs in conjunction with faster and less light-sensitive ChR mutants, such as ChR2-H134R, and to ensure robust control over action potential firing, higher OLED brightness will be favorable. At present, the maximum achievable brightness of our OLED arrays is limited by the CMOS driver electronics. In principle, OLEDs can achieve substantially higher brightness, in particular because pulsed operation and small active areas can be used for optogenetic control. At very high brightness, OLED efficiency typically decreases because of bimolecular annihilation processes and Joule heating, an effect known as roll-off or droop (37). However, there are various strategies for mitigating roll-off, and OLEDs have been operated at currents of tens of amperes per square centimeter without drastic loss in efficiency (38).

The most appealing feature of OLEDs in the context of optogenetics is their ability to provide fine spatial control over the area of illumination in a lens-free configuration. In previous work, we demonstrated the use of OLED arrays to control the phototaxis of freely swimming single-cell freshwater algae (32). However, the algae cells were not attached to the OLED array, and in addition, they were naturally light-sensitive. Here, we have demonstrated that OLED microarrays can be used for optogenetic manipulation of individual live cells from the HEK cell line that express the light-sensitive ChR mutant C128S/D156A. In contrast to earlier work, these cells adhered to the array, were genetically modified to be sensitive to light, and showed subtle changes in physiology. This paves the way for using OLEDs to investigate the function and operation of neuronal networks. Compared to other light sources, such as arc lamps, lasers, or LEDs, OLED arrays combine high spatial resolution and close contact between cells and light source with the ability for complex light-pattern generation. In the future, the light pattern provided by OLED arrays can be configured to achieve optimal illumination of the cell (or cells) of interest while minimizing light delivery to neighboring cells. Complex patterned illumination will also facilitate activation of multiple specific cells of interest within a complex network while leaving other cells unaffected. Alternatively, subcellular components (for example, axon, soma, and dendrites) may be addressed. Because of their fast dynamic reconfigurability, OLED arrays provide an ideal platform to perform optogenetic experiments that require high spatiotemporal resolution, for example, to study signaling processes in networks of cultured neurons. In the present configuration, the maximum speed at which the illumination pattern can be reconfigured (120 Hz, 8 ms) is given by the CMOS driver electronics. Although this may already be sufficient in many cases, the fundamental limit to switching time is the exciton lifetime of organic emitters, which is in the nanosecond range, that is, much shorter than the neuronal processes that one would study with optogenetic tools.

Finally, chemical tuning of organic semiconductors allows one to adjust their physical properties over a wide range. For instance, the emission spectrum of OLEDs could be readily matched to the action spectrum of any future ChR mutants. By using stacked devices with two separately controllable OLEDs emitting light of different colors (20, 39), one may even be able to simultaneously control two or more colocated light-sensitive targets.

Considering these unique advantages of OLED microarrays and the rate at which the OLED technology has advanced in the past, we believe that OLEDs are ideally positioned to develop into a useful platform technology for investigating and controlling biological processes in single cells or whole organisms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

OLED microarrays

OLED microarrays were obtained from Fraunhofer FEP. They are based on a CMOS backplane with an active area of approximately 20 mm2 and 230,000 individually addressable pixels, each defined by a 6 × 9 μm2–sized aluminum anode. Each microarray is bonded to a flexible flat cable that connects to a custom HDMI driver interface. The brightness of all OLEDs in the array can be adjusted by tuning the voltage supplied to the common cathode. However, at large negative cathode bias, pixels in the off state also begin to emit light. To prevent this, for all results presented here, the cathode voltage was set to 3 V, which yielded an optical power density of 1 W m−2. The arrays were operated at a frame rate of 60 Hz, and the digital brightness level was set to 255.

Electrical and optical characterization of OLED microarrays

The optical power density was measured with a calibrated power meter (Gentec-EO) for a range of cathode voltages. The emission spectrum was recorded with a charge-coupled device spectrometer (Andor).

Cell proliferation and viability on OLED microarrays

Wild-type HEK cells (HEK-293wt) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. HEK-293 cells stably expressing ChR2-H134R-EYFP (a ChR2 mutant fused to enhanced yellow fluorescent protein; HEK-293R) were provided by M. Antkowiak and F. J. Gunn-Moore (both University of St Andrews). All cell lines were cultured on standard tissue culture flasks and dishes (Greiner Bio-One) in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (high glucose, with GlutaMAX; Life Technologies) with 10 volume % fetal calf serum (Biochrom) and 1 volume % penicillin-streptomycin (10,000 U/ml; Life Technologies). Cells were maintained at 37°C, 5% CO2, and 95% humidity. OLED arrays were successively coated with poly-l-lysine [0.1 mg/ml in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS); Biochrom] for at least 30 min at room temperature and with fibronectin (1 mg/ml in PBS; Life Technologies) for at least 1 hour at 37°C. Seeding density for the cells was 700/cm2 for the proliferation and cell survival experiments, and 125,000 cells/cm2 for the optogenetics experiments. The OLED arrays were fully immersed into the medium during cell culture. Imaging of cells on standard culture dishes was performed with an inverted microscope under dia-illumination (phase contrast), whereas images of the cells on OLED arrays were taken with an upright microscope under epi-illumination with a mercury arc lamp and either a beam splitter or a set of fluorescence filters.

Transient cell transfection

The plasmid pAAV-CaMKIIα-hChR2(C128S/D156A)-mCherry (Addgene, 35502, K. Deisseroth) was amplified using E.Z.N.A. Plasmid Mini Kit II (Omega Bio-tek) and stored at −80°C. For transfection, the Lipofectamine 3000 kit (Life Technologies) was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Final concentrations of Lipofectamine 3000 (3 μl/ml), P3000 reagent (2 μl/ml), and plasmid DNA (1 μg/ml) were applied. Cells were transferred from the culture dish onto the OLED arrays 48 hours after transfection using Trypsin-EDTA (0.25%; Life Technologies) and kept on the arrays in culture medium containing 1 μM all-trans retinal (Sigma-Aldrich) for 24 hours before electrophysiological measurements.

Optical stimulation

For optical stimulation, the appropriate video signals (with either the entire array on or three selected pixels on) were sent to the OLED microarrays via the HDMI controller. HEK-293S+A cells were deactivated with green light (560/40-nm band-pass filter; Chroma) from a 120-W mercury arc lamp (X-Cite series 120Q; Lumen Dynamics).

Electrophysiological measurements

Whole-cell patch clamp recordings were performed on HEK-293wt (wild-type), HEK-293R (H134R mutant), and HEK-293S+A (C128S/D156A mutant) cells. During the measurement, cells were kept at room temperature and perfused with oxygenated (95% oxygen, 5% CO2) artificial cerebral spinal fluid (127 mM NaCl, 1.25 mM KCl3, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, 26 mM NaHCO3, and 10 mM glucose). Imaging of the cells was done under epi-illumination with an upright microscope and light from a 120-W mercury arc lamp filtered with a 600-nm long-pass filter. Patch clamp capillaries (approximately 6-megohm resistance) were pulled on a horizontal puller (Sutter Instrument) from borosilicate glass (World Precision Instruments) and filled with an internal solution containing 140 mM KMeSO4, 10 mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 10 mM Hepes, 1 mM EGTA, and 3 mM Mg-ATP (adenosine triphosphate). For whole-cell patch clamp recordings, the patch capillary was pressed against the cell membrane. A small piece of membrane was pulled into the pipette via suction, creating a tight seal between the membrane and pipette. Stronger suction broke the patch of membrane so that the electrode within the pipette was in contact with the intracellular space. The holding potential, that is, the potential difference between the inside of the cell and the outside (measured with the patch electrode relative to the ground electrode), was fixed to −60 mV and the resulting membrane current was measured (voltage clamp mode). Signals were amplified and filtered (4-kHz low-pass Bessel filter) with a MultiClamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices) and acquired at 50 kHz using a Digidata 1440A A/D board and pCLAMP software (Molecular Devices).

Analysis of the patch clamp recordings

Data were analyzed using Clampfit software (Molecular Devices). The mean current changes quoted in the text corresponded to the difference between the current during light stimulation and the current before/after light stimulation. To improve the signal-to-noise ratio, the current was averaged over 5 s in each case. To account for possible baseline shifts, the mean of the current before and after light stimulation was used. Statistical significance was tested for via Mann-Whitney U test for the sample groups HEK-293wt/HEK-293R and HEK-293wt/HEK-293S+A (Fig. 4, D and E). For the representative patch clamp recordings in Figs. 4 and 5, data were reduced to 10 Hz and filtered with an eight-pole Bessel filter (cutoff, 100 Hz). For the data shown in Fig. 5, the current change is calculated by temporal averaging over a 5-s time window as above.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Morton and C. Murawski (both University of St Andrews) and B.Richter (Fraunhofer FEP, Dresden) for fruitful discussions. HEK-293 cells that were stably transfected with ChR2-H134R-EYFP DNA were provided by M. Antkowiak and F. J. Gunn-Moore (both University of St Andrews). Funding: This work was supported by the Scottish Funding Council (via Scottish Universities Physics Alliance), the Human Frontier Science Program (RGY0074/2013), and the RS Macdonald Charitable Trust. Author contributions: A.S. performed the optogenetics experiments and data analysis. E.C.W. and G.B.M. carried out the patch clamp measurements. M.C.G. conceived and supervised the project. A.S. and M.C.G. jointly wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper. The research data supporting this publication can be accessed at DOI 10.17630/d758df2c-78ee-482c-ae7f-af37b00fdb52. Additional data related to this paper are available upon request from M.C.G. (mcg6@st-andrews.ac.uk).

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Miller G., Shining new light on neural circuits. Science 314, 1674–1676 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deisseroth K., Optogenetics: 10 years of microbial opsins in neuroscience. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 1213–1225 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyden E. S., Zhang F., Bamberg E., Nagel G., Deisseroth K., Millisecond-timescale, genetically targeted optical control of neural activity. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 1263–1268 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berndt A., Yizhar O., Gunaydin L. A., Hegemann P., Deisseroth K., Bi-stable neural state switches. Nat. Neurosci. 12, 229–234 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hochbaum D. R., Zhao Y., Farhi S. L., Klapoetke N., Werley C. A., Kapoor V., Zou P., Kralj J. M., Maclaurin D., Smedemark-Margulies N., Saulnier J. L., Boulting G. L., Straub C., Cho Y. K., Melkonian M., Wong G. K.-S., Harrison D. J., Murthy V. N., Sabatini B. L., Boyden E. S., Campbell R. E., Cohen A. E., All-optical electrophysiology in mammalian neurons using engineered microbial rhodopsins. Nat. Methods 11, 825–833 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klapoetke N. C., Murata Y., Kim S. S., Pulver S. R., Birdsey-Benson A., Cho Y. K., Morimoto T. K., Chuong A. S., Carpenter E. J., Tian Z., Wang J., Xie Y., Yan Z., Zhang Y., Chow B. Y., Surek B., Melkonian M., Jayaraman V., Constantine-Paton M., Wong G. K.-S., Boyden E. S., Independent optical excitation of distinct neural populations. Nat. Methods 11, 338–346 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antkowiak M., Torres-Mapa M. L., Witts E. C., Miles G. B., Dholakia K., Gunn-Moore F. J., Fast targeted gene transfection and optogenetic modification of single neurons using femtosecond laser irradiation. Sci. Rep. 3, 3281 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yizhar O., Fenno L. E., Prigge M., Schneider F., Davidson T. J., O’Shea D. J., Sohal V. S., Goshen I., Finkelstein J., Paz J. T., Stehfest K., Fudim R., Ramakrishnan C., Huguenard J. R., Hegemann P., Deisseroth K., Neocortical excitation/inhibition balance in information processing and social dysfunction. Nature 477, 171–178 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chuong A. S., Miri M. L., Busskamp V., Matthews G. A. C., Acker L. C., Sørensen A. T., Young A., Klapoetke N. C., Henninger M. A., Kodandaramaiah S. B., Ogawa M., Ramanlal S. B., Bandler R. C., Allen B. D., Forest C. R., Chow B. Y., Han X., Lin Y., Tye K. M., Roska B., Cardin J. A., Boyden E. S., Noninvasive optical inhibition with a red-shifted microbial rhodopsin. Nat. Neurosci. 17, 1123–1129 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pisanello F., Sileo L., Oldenburg I. A., Pisanello M., Martiradonna L., Assad J. A., Sabatini B. L., De Vittorio M., Multipoint-emitting optical fibers for spatially addressable in vivo optogenetics. Neuron 82, 1245–1254 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abaya T. V. F., Diwekar M., Blair S., Tathireddy P., Rieth L., Clark G. A., Solzbacher F., Characterization of a 3D optrode array for infrared neural stimulation. Biomed. Opt. Express 3, 2200–2219 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grossman N., Poher V., Grubb M. S., Kennedy G. T., Nikolic K., McGovern B., Berlinguer Palmini R., Gong Z., Drakakis E. M., Neil M. A. A., Dawson M. D., Burrone J., Degenaar P., Multi-site optical excitation using ChR2 and micro-LED array. J. Neural. Eng. 7, 016004 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McAlinden N., Gu E., Dawson M. D., Sakata S., Mathieson K., Optogenetic activation of neocortical neurons in vivo with a sapphire-based micro-scale LED probe. Front. Neural Circuits 9, 25 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim T.-i., McCall J. G., Jung Y. H., Huang X., Siuda E. R., Li Y., Song J., Song Y. M., Pao H. A., Kim R.-H., Lu C., Lee S. D., Song I.-S., Shin G., Al-Hasani R., Kim S., Tan M. P., Huang Y., Omenetto F. G., Rogers J. A., Bruchas M. R., Injectable, cellular-scale optoelectronics with applications for wireless optogenetics. Science 340, 211–216 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park S. I., Brenner D. S., Shin G., Morgan C. D., Copits B. A., Chung H. U., Pullen M. Y., Noh K. N., Davidson S., Oh S. J., Yoon J., Jang K.-I., Samineni V. K., Norman M., Grajales-Reyes J. G., Vogt S. K., Sundaram S. S., Wilson K. M., Ha J. S., Xu R., Pan T., Kim T.-i., Huang Y., Montana M. C., Golden J. P., Bruchas M. R., Gereau R. W. IV, Rogers J. A., Soft, stretchable, fully implantable miniaturized optoelectronic systems for wireless optogenetics. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 1280–1286 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reineke S., Lindner F., Schwartz G., Seidler N., Walzer K., Lüssem B., Leo K., White organic light-emitting diodes with fluorescent tube efficiency. Nature 459, 234–238 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uoyama H., Goushi K., Shizu K., Nomura H., Adachi C., Highly efficient organic light-emitting diodes from delayed fluorescence. Nature 492, 234–238 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCarthy M. A., Liu B., Donoghue E. P., Kravchenko I., Kim D. Y., So F., Rinzler A. G., Low-voltage, low-power, organic light-emitting transistors for active matrix displays. Science 332, 570–573 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiao L., Chen Z., Qu B., Luo J., Kong S., Gong Q., Kido J., Recent progresses on materials for electrophosphorescent organic light-emitting devices. Adv. Mater. 23, 926–952 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fröbel M., Schwab T., Kliem M., Hofmann S., Leo K., Gather M. C., Get it white: Color-tunable AC/DC OLEDs. Light Sci. Appl. 4, e247 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Z. B., Helander M. G., Qiu J., Puzzo D. P., Greiner M. T., Hudson Z. M., Wang S., Liu Z. W., Lu Z. H., Unlocking the full potential of organic light-emitting diodes on flexible plastic. Nat. Photonics 5, 753–757 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han T.-H., Lee Y., Choi M.-R., Woo S.-H., Bae S.-H., Hong B. H., Ahn J.-H., Lee T.-W., Extremely efficient flexible organic light-emitting diodes with modified graphene anode. Nat. Photonics 6, 105–110 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krotkus S., Ventsch F., Kasemann D., Zakhidov A. A., Hofmann S., Leo K., Gather M. C., Photo-patterning of highly efficient state-of-the-art phosphorescent OLEDs using orthogonal hydrofluoroethers. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2, 1043–1048 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vogel U., Wartenberg P., Richter B., Brenner S., Thomschke M., Fehse K., Baumgarten J., Paper No S16.1: SVGA bidirectional OLED microdisplay for near-to-eye projection. Dig. Tech. Pap. Soc. Inf. Disp. Int. Symp. 46, 66 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park J.-S., Chae H., Chung H. K., Lee S. I., Thin film encapsulation for flexible AM-OLED: A review. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 26, 034001 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Attili S. K., Lesar A., McNeill A., Camacho-Lopez M., Moseley H., Ibbotson S., Samuel I. D. W., Ferguson J., An open pilot study of ambulatory photodynamic therapy using a wearable low-irradiance organic light-emitting diode light source in the treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Br. J. Dermatol. 161, 170–173 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang C., Hwang D., Yu Z., Takei K., Park J., Chen T., Ma B., Javey A., User-interactive electronic skin for instantaneous pressure visualization. Nat. Mater. 12, 899–904 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lefèvre F., Chalifour A., Yu L., Chodavarapu V., Juneau P., Izquierdo R., Algal fluorescence sensor integrated into a microfluidic chip for water pollutant detection. Lab Chip 12, 787–793 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gather M. C., Kronenberg N. M., Meerholz K., Monolithic integration of multi-color organic LEDs by grayscale lithography. Adv. Mater. 22, 4634–4638 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park J., Noh Y.-Y., Huh J. W., Lee J., Chu H., Optical and barrier properties of thin-film encapsulations for transparent OLEDs. Org. Electron. 13, 1956–1961 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 31.L. Moro, D. Boesch, X. Zeng, in OLED Fundamentals, Materials, Devices, and Processing of Organic Light-Emitting Diodes, D. J. Gaspar, E. Polikarpov, Eds. (CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, 2015), pp. 25–66. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steude A., Jahnel M., Thomschke M., Schober M., Gather M. C., Controlling the behavior of single live cells with high density arrays of microscopic OLEDs. Adv. Mater. 27, 7657–7661 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagel G., Brauner M., Liewald J. F., Adeishvili N., Bamberg E., Gottschalk A., Light activation of channelrhodopsin-2 in excitable cells of Caenorhabditis elegans triggers rapid behavioral responses. Curr. Biol. 15, 2279–2284 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meyer J., Görrn P., Bertram F., Hamwi S., Winkler T., Johannes H.-H., Weimann T., Hinze P., Riedl T., Kowalsky W., Al2O3/ZrO2 nanolaminates as ultrahigh gas-diffusion barriers—A strategy for reliable encapsulation of organic electronics. Adv. Mater. 21, 1845–1849 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 35.E. G. Jones, A. Peters, P. S. Ulinski, Cerebral Cortex: Models of Cortical Circuits, (Springer, Boston, MA, 1999). [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Leary T., van Rossum M. C. W., Wyllie D. J. A., Homeostasis of intrinsic excitability in hippocampal neurones: Dynamics and mechanism of the response to chronic depolarization. J. Physiol. 588, 157–170 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murawski C., Leo K., Gather M. C., Efficiency roll-off in organic light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 25, 6801–6827 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hayashi K., Nakanotani H., Inoue M., Yoshida K., Mikhnenko O., Nguyen T.-Q., Adachi C., Suppression of roll-off characteristics of organic light-emitting diodes by narrowing current injection/transport area to 50 nm. Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 093301 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shen Z., Burrows P. E., Bulović V., Forrest S. R., Thompson M. E., Three-color, tunable, organic light-emitting devices. Science 276, 2009–2011 (1997). [Google Scholar]