Researchers find the proton conductivity of jelly found in the Ampullae of Lorenzini of sharks and skates to be unusually high.

Keywords: proton conductors, Ampullae of Lorenzini, Sharks, Skates, electrosensing cells, Elasmobranchii, hydrogels

Abstract

In 1678, Stefano Lorenzini first described a network of organs of unknown function in the torpedo ray—the ampullae of Lorenzini (AoL). An individual ampulla consists of a pore on the skin that is open to the environment, a canal containing a jelly and leading to an alveolus with a series of electrosensing cells. The role of the AoL remained a mystery for almost 300 years until research demonstrated that skates, sharks, and rays detect very weak electric fields produced by a potential prey. The AoL jelly likely contributes to this electrosensing function, yet the exact details of this contribution remain unclear. We measure the proton conductivity of the AoL jelly extracted from skates and sharks. The room-temperature proton conductivity of the AoL jelly is very high at 2 ± 1 mS/cm. This conductivity is only 40-fold lower than the current state-of-the-art proton-conducting polymer Nafion, and it is the highest reported for a biological material so far. We suggest that keratan sulfate, identified previously in the AoL jelly and confirmed here, may contribute to the high proton conductivity of the AoL jelly with its sulfate groups—acid groups and proton donors. We hope that the observed high proton conductivity of the AoL jelly may contribute to future studies of the AoL function.

INTRODUCTION

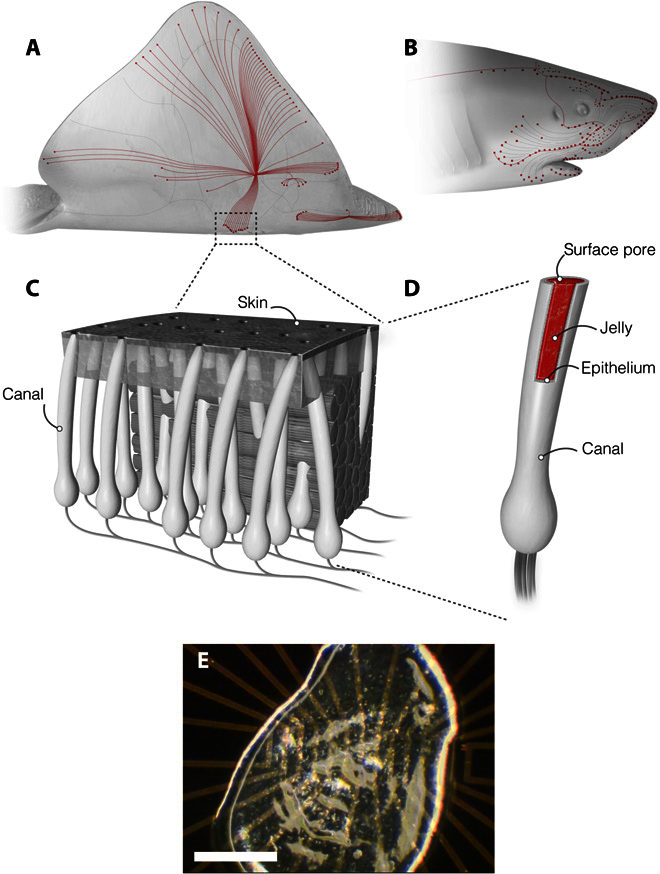

In 1678, Stefano Lorenzini observed long, tubular structures in the torpedo ray (1). Named the ampullae of Lorenzini (AoL) in Lorenzini’s honor, these organs are also present in sharks and skates (Fig. 1, A and B). The function of the AoL remained a mystery for almost 300 years, until Murray (2) inferred their electrosensory function in 1960. The AoL allow sharks, skates, and rays to detect changes in electric fields generated by muscle contractions and the physiology of their potential prey (3). An individual ampulla consists of a pore through the skin that opens to the aquatic environment. This pore is connected to a collagen canal enclosing an epithelium that secretes a jelly-like substance (AoL jelly). This canal runs subdermally to an alveolus that contains electrosensitive cells (Fig. 1C) (4). Within the alveolus, the electrosensitive cells of the ampullae communicate with neurons (4). Remarkably, the integration of signals from many ampullae allows sharks, skates, and rays to detect changes in the electric fields as small as 5 nV/cm (5–7). It is likely that the electrical properties of the AoL jelly play a key role in this mechanism. How such weak electric fields transmit along the AoL canal to electrosensory cells is subject to debate (6, 7). Different electrical properties of the AoL jelly are reported in the literature (8–11). The AoL jelly is reported either as a semiconductor with temperature dependence conductivity and thermoelectric behavior (8, 9) or as a simple ionic conductor with the same electrical properties as the surrounding seawater (10, 11). Here, using proton-conducting devices, we demonstrate that the AoL jelly is a remarkable proton-conducting material, and we speculate that the polyglycans contained in the AoL jelly may contribute to its proton conductivity.

Fig. 1. The AoL.

(A and B) Skates and sharks locate their prey by detecting the weak electric fields naturally generated by biomechanical activity. (C) A network of electrosensory organs called the AoL is responsible for this sense. (D) An individual ampulla consists of a surface pore connected to a set of electrosensory cells by a long jelly-filled canal. Sharks and skate can sense fields as small as 5 nV/cm despite canals traveling through up to 25 cm of noisy biological tissue. (E) A sample of the AoL jelly on an electrical device is presented. Scale bar, 0.5 mm.

RESULTS

Materials observations

We collected samples by squeezing AoL jelly from visible surface pores on the skin of bonnethead shark (Sphyrna tiburo), longnose skate (Raja rhina), and big skate (Raja binoculata) (Fig. 1, A and B, and fig. S1). After storing at −20°C, we deposited the AoL jelly directly onto the sample surface without further processing. For all species, the resulting AoL jelly is thick, viscous, and optically clear (Fig. 1E). We exposed AoL jelly samples to 90% relative humidity (RH) for 30 min and hydrated them to 97% water content as measured by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) (fig. S2). This water content is consistent with previous reports (10, 11). If allowed to dry in air, the volume of the sample decreases by approximately 80%, corroborating the known fact that the jelly is a hydrogel with a high water content.

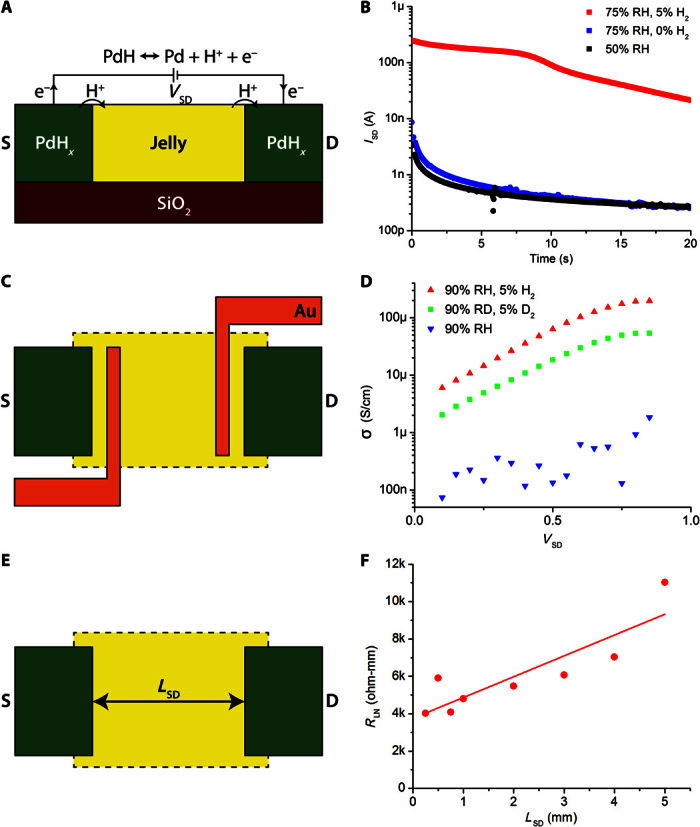

dc electrical measurements with PdHx proton-conducting contacts

We performed initial electrical measurements in a standard two-terminal geometry with palladium (Pd) source and drain contacts (Fig. 2A) (12–15). When Pd is exposed to hydrogen, Pd forms palladium hydride (PdHx) with a stoichiometric ratio x ≤ 0.6. With a source-drain potential difference, VSD, the PdHx source and drain inject and drain protons (H+) into and from the AoL jelly samples, effectively serving as protodes (12–15). For each H+ injected into the AoL jelly, an excess electron is collected by the leads, which complete the circuit and result in a current measured at the drain, ID (Fig. 2A). For an applied VSD = 1 V, we measured ID at room temperature as a function of time (t) in an atmosphere of nitrogen or hydrogen with controlled RH, as we have previously done for the biopolymer melanin (16). For RH = 50%, the AoL jelly samples extracted from R. rhina have very low electrical conductivity with ID ~ 3 nA when measured with electrically conducting and proton-blocking Pd contacts exposed to nitrogen (Fig. 2B, black curve). At low RH, the only contribution to ID is likely from electrons, because ions and protons require a highly hydrated material to conduct (17). For RH = 75%, ID increases with a 10-nA peak when measured with Pd contacts (Fig. 2B, blue curve). The formation of a Debye layer from the ions blocked at the contact–AoL jelly interface causes ID to rapidly decrease to 0.3 nA at t = 20 s. Because Pd contacts block ions and protons, ID = 10 nA is likely the ionic component to the transient current in the AoL jelly, which contains the same ionic species as seawater (table S1) (11). The observed capacitance (22 nF) is consistent with the estimated capacitance for ionic charging of the Pd–AoL jelly interface (26 nF) (table S1). We observed a similar behavior for ionic currents in the biopolymer melanin (16). This ionic component corresponds to an ionic conductivity of the AoL jelly, σion = 100 nS/cm. This σion is rather low compared to the conductivity of seawater (≈40 mS/cm), which was also attributed to the AoL jelly by previous work (11). However, larger ions such as Na+ and Cl− require larger pores in the material to be able to diffuse, and low ionic conductivity of the AoL jelly was also previously observed (18). For proton-conducting PdHx contacts at 75% RH, ID peaks at 250 nA, indicating a strong component of proton conductivity (Fig. 2B, red trace). This proton conductivity is consistent with the activation energy for the conductivity of shark AoL jelly (11). With PdHx contacts, ID drops over time. At first sight, this time dependence may suggest proton-blocking behavior at the contact. However, we observed similar time dependence when measuring highly proton-conducting materials such as Nafion with PdHx contacts (14). This time dependence arises when the diffusion of hydrogen to the PdHx contact surface is slower than the conduction of H+ in the proton-conducting material (14).

Fig. 2. Proton conduction in ampullae jelly.

(A) Palladium hydride (PdHx) protode behavior. Under an applied voltage, PdH contacts split into Pd, H+, and e−. Protons are injected into the skate jelly, whereas electrons travel through external circuitry and are measured. (B) Transient response to a 1-V applied signal in AoL jelly from R. rhina. The proton current (red) is 50 times larger than the ion current (blue). The electron current (black) is slightly smaller than the ion current. (C) Four-point probe geometry. Distinct Au contacts are used to measure voltage within the channel and to correct for any potential drop at the PdH-jelly interface. (D) Four-point probe conductivity results from R. binoculata. Conductivity increases exponentially with voltage up to about 1 V, suggesting that conduction is limited by potential barriers. Deuterium conductivity (green) at 90% D2O humidity (RD) is half as large as proton conductivity (red) for all voltages. Ion conduction in the hydrated state (blue) is minimal. (E) TLM geometry. Varying the distance between source and drain (LSD) distinguishes between the fixed PdH-jelly interface resistance and the varying bulk resistance. (F) RLN as a function of LSD for R. binoculata. A linear fit gives a bulk material proton conductivity of 1.8 ± 0.9 mS/cm.

We also measured the proton conductivity (σH+) of AoL jelly extracted from big skate (R. binoculata) and bonnethead shark (S. tiburo) (fig. S3). The AoL jelly for all species is proton-conducting with a fivefold range in σH+. The AoL jelly from big skate is more conducting than the AoL jelly from bonnethead shark, which is, in turn, more conducting than the AoL jelly from longnose skate. The time dependence of ID is consistent with the differences in σH+ and our previous observations with Nafion (14). Although it is likely that some differences in σH+ across species are intrinsic to the AoL jelly, the small differences in σH+ measured with these devices may also arise because of variance in device geometry. It would be certainly of interest to perform a systematic study of the AoL jelly conductivity across species, as well as age and gender of the subjects.

Four-point probe measurement and kinetic isotope effect

The injection of protons from the contact into the AoL jelly incurs a significant contact resistance, and the depletion of H at the PdHx contacts causes a drop in ID as observed in our previous work (14). To circumvent these issues, we used a modified four-point probe geometry to measure the proton conductivity (σH+) of the AoL jelly independently of the PdHx–AoL jelly contact resistance. In this geometry, we added two thin Au contacts between the Pd source and drain, for a total of four contacts. When we apply VSD to the PdHx source and drain, a current of H+ flows in the AoL jelly, as demonstrated in the standard two-probe geometry. We measured the potential difference between the two Au contacts. This potential difference is proportional to ID and inversely proportional to the conductivity of the AoL jelly (Fig. 2C). Because no current flows across the Au–AoL jelly interface, there is no potential drop and the PdHx contact resistance does not affect the measurement of the conductivity of the AoL jelly. For Pd contacts at 90% RH, we find σion ≈ 100 to 1000 nS/cm depending on VSD (Fig. 2D, blue trace), which is consistent with our observations in the two-probe geometry (Fig. 2B). For PdHx contacts at 90% RH, we find σH+ ≈ 6 to 200 μS/cm, peaking at 200 μS/cm for VSD = 1 V (Fig. 2D, red trace). This conductivity is similar to that of dialyzed AoL jelly from a shark in a dc measurement (800 μS/cm) (11). In our measurements, the proton conductivity of the AoL jelly depends exponentially on VSD, which is similar to the highly proton-conducting polymer Nafion (19). To confirm that the AoL jelly conductivity arises from H+, we repeated the measurements by hydrating the sample with deuterated water and by exposing the Pd to deuterium rather than to hydrogen. Deuterium ions (D+) transport along hydrated materials in a similar fashion as protons, but with lower mobility and associated lower conductivity (20). Hydrating the AoL jelly samples with D2O substitutes D+ for H+ in the material. A subsequent decrease in conductivity for D+ (σD+)—the kinetic isotope effect—is a well-accepted signature for conductivity arising predominantly from protons (20). For the AoL jelly, σD+ = 1/2σH+ for any VSD when measured in the four-point probe geometry (Fig. 2D, green trace). The kinetic isotope effect with this four-point probe measurement unequivocally points to proton conduction in the AoL jelly (20). However, these measurements likely underestimate the AoL jelly conductivity (σH+ = 0.2 mS/cm). In the four-point probe geometry, we find the proton conductivity of Nafion at σH+ = 2 mS/cm, which is lower than the literature value (σH+ = 78 mS/cm) (21). This measured conductivity of the Nafion control sample is smaller than expected. We suspect that non-ideal geometry is the cause of this variation. The calculated conductivity assumes that only the material in the channel is relevant to conduction, because the electric field is highest here. However, if the interface resistance is comparable to the channel resistance, this assumption may not be accurate, skewing the calculated results (22). To address this variation, we measured the proton conductivity of the AoL jelly in a transmission line geometry.

Transmission line measurement

We constructed devices with different lengths between the Pd source and the drain to estimate the proton conductivity of the AoL jelly (Fig. 2E). This varying source-drain length (LSD) geometry is commonly known as a transmission line measurement (TLM) (Fig. 2E) (23). We applied VSD = 1 V on devices with LSD ranging from 0.25 to 5.0 mm, measured ID, and calculated the resistance of each device, RL. Because different devices contained AoL jelly of different thicknesses, we multiplied RL by the AoL jelly thickness to get the normalized resistance RLN and plotted RLN as a function of LSD (Fig. 2F). In this geometry, the resistance of the AoL jelly increases linearly with LSD, but the contact resistance at the source–AoL jelly and drain–AoL jelly interface is constant. To extrapolate the resistivity of the AoL jelly, we plot RLN as a function of LSD. The slope of this plot is proportional to the resistivity of the AoL jelly, and the intercept on the RLN axis for LSD = 0 is the contact resistance. For the AoL jelly, we obtain σH+ = 1.8 ± 0.9 mS/cm, which is only one order of magnitude lower than the proton conductivity of Nafion σH+ = 28 ± 14 mS/cm measured in the same geometry (fig. S4). The proton conductivity of the Nafion control sample (28 ± 14 mS/cm) measured in a TLM geometry is much closer to the reported value of 78 mS/cm (21). Therefore, we conclude that σH+ = 1.8 ± 0.9 mS/cm measured for the AoL jelly in the TLM geometry is our best estimate of the proton conductivity of the AoL jelly.

Materials characterization

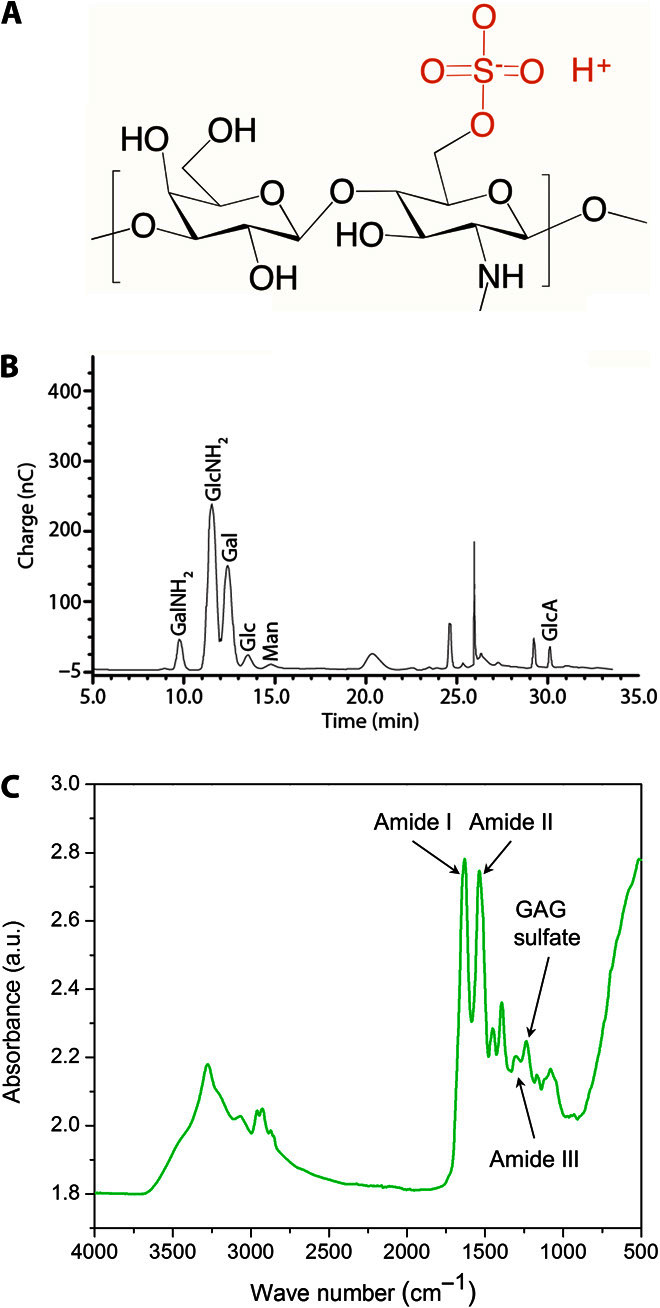

When working with biological materials, characterization is often challenging because many components are present and further processing to separate these components may change the materials properties and function. Here, we chose to perform a preliminary analysis on the as-extracted AoL jelly to look for the components that might provide the high protonic conductivity. Although the AoL jelly likely contains a mixture of proteins and polyglycans, we focus on the sulfated polyglycan keratan sulfate (KS) (Fig. 3A) following an early report by Doyle (24). We characterized the AoL jelly from the skate (R. binoculata) using monosaccharide compositional analysis and Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. In the monosaccharide composition analysis, we find a nearly 1:1 ratio of glucosamine to galactose (Fig. 3B). This ratio is consistent with the presence of KS in the AoL jelly and corroborates Doyle’s analyses (24). However, the presence of other sulfated polyglycans or polysaccharides cannot be completely ruled out at this time. The FTIR spectrum of the AoL skate jelly also contains the signature peaks of KS (Fig. 3C), including the peak at 1238 cm−1 attributed to S=O vibrations of the sulfate group (25). The sulfate group in the KS is an acid [pKa (where Ka is the acid dissociation constant) = 2] (26), which donates the protons that contribute to the proton conductivity of the material (13, 15). By comparison, the sulfonic group in Nafion is a stronger acid, so Nafion has correspondingly higher charge carrier density and proton conductivity (21). However, proton conduction requires both a high carrier density and a high carrier mobility, so creating pathways for proton transport is also essential. KS has several hydrophilic groups that may induce the organization of water in the AoL jelly into hydrogen bond chains, allowing proton conduction according to the Grotthuss mechanism (27). Chitin-derived polysaccharides functionalized with acid and base groups are also good proton conductors and have chemical similarities to KS (12, 13). Charged amino acids in the squid protein reflectin also contribute to its high proton conductivity (28, 29). Further investigations into the composition and microstructure of the AoL jelly and its correlation to the AoL jelly proton conductivity across species are necessary to create a complete picture of the AoL high proton conductivity.

Fig. 3. Chemical characterization of jelly.

(A) Structure of KS, which may be present in the skate (R. binoculata) AoL jelly. Proton conduction in a sulfated polymer is consistent with known conducting materials, such as Nafion or modified chitosan. (B) Compositional analysis of skate jelly from R. binoculata. The peaks denote the presence of different monomers (GalNH2, galactosamine; GlcNH2, glucosamine; Gal, galactose; Glc, glucose; Man, mannose; GlcA, glucuronic acid). Glucosamine and galactose, the two components of KS, are found in highest abundance. An equimolar ratio of glucosamine to galactose would be expected for KS; the slightly higher abundance of glucosamine suggests the presence of other polysaccharides in the jelly. (C) Full-scale FTIR spectrum of the skate jelly showing characteristic peaks of sulfated glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), specifically KS. a.u., arbitrary units.

DISCUSSION

With two and four terminal devices using proton-conducting PdHx contacts, we measured the proton conductivity of the jelly extracted from the AoL of skates and sharks. The proton conductivity of the AoL jelly is as high as σH+ = 2 mS/cm. This value is the highest reported for the proton conductivity of any biological material, and it is only 40 times lower than the proton conductivity for Nafion, the current state-of-the-art polymer proton conductor (table S2). We performed preliminary characterization of the AoL jelly, and we reconfirmed the presence of the polyglycan KS. We propose that the high proton conductivity of the AoL jelly may arise from protons donated by the KS acid groups to the water contained in the hydrated jelly. This high proton conductivity of the AoL jelly is remarkable, and we hope that the observation of this conductivity may contribute to future studies of the AoL electrosensing function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

AoL jelly preparation

We extracted AoL jelly from freshly caught and recently expired R. binoculata (big skate), R. rhina (longnose skate), and S. tiburo (bonnethead shark). AoL jelly was pressed from visible surface pores and collected with a mechanical plunger-style pipette. Samples were stored at −20°C until use. Just before measurement, the AoL jelly was thawed at room temperature and then spun in a centrifuge at 6000 rpm to remove air bubbles. The AoL jelly was then drop-cast onto substrates using a syringe. Because of the thick, viscous nature of the AoL jelly, precise volume control was difficult.

Electrical measurements

Electrical measurements were performed on a Signatone H-100 probe station using a custom atmospheric isolation chamber. Dakota Instruments mass flow controllers were used to set the ratio of dry nitrogen, wet nitrogen, hydrogen, and deuterium controlled by a LabView DAQ. An Agilent 4155C semiconductor parameter analyzer was used for all electrical measurements.

dc transient measurements

Two-terminal measurements were performed on Si substrates with a 100-nm SiO2 layer. Pd contacts were deposited by conventional photolithography and e-beam evaporation. Contacts were 30 μm wide with a 1-μm separation. The Pd contacts were 60 nm thick with a 5-nm Cr adhesion layer. The AoL jelly layer was typically 50 μm thick.

Kinetic isotope effect measurements

Samples were saturated with either water (H2O) and hydrogen gas (H2) or deuterated water (D2O) and deuterium gas (D2). Samples were held for 30 min after switching to allow the diffusive exchange of ions.

Transmission line measurements

Samples consisted of 100-nm Pd contacts with a 5-nm Cr adhesion layer deposited on glass slides. Mylar shadow masks were used to define 5-mm-wide contacts with LSD = 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, and 5.0 mm. The sample thickness was usually around 1 mm. Measurements were performed at VSD = 1 V.

Four-point probe measurements

Samples were fabricated on Si wafers with a 100-nm SiO2 layer. Conventional photolithography was used to separately pattern Pd and Au contacts. Pd contacts were 30 μm wide and 60 nm thick and were separated by a 6-μm gap. Two Au contacts were deposited between the Pd contacts. Au contacts were 50 nm thick and 1 μm wide and were separated by a 1.5-μm gap. Both Pd and Au contacts had a 5-nm Cr adhesion layer. The AoL jelly layer was typically 50 μm thick.

Compositional analysis

An AoL jelly sample was taken from a freshly caught and recently expired skate (R. binoculata). This sample was separated into 0.5-ml aliquots and frozen at −80°C. One of the aliquots was sent to the Biotechnology Core Resources Laboratory in San Diego and used for monosaccharide compositional analysis via high-performance anion exchange chromatography (HPAEC) with pulsed amperometric detection (PAD). The sample (0.1 mg) was treated with 200 μl of 2 M trifluoroacetic acid at 100°C for 4 hours to cleave all glycosidic linkages and processed further for monosaccharide composition and detection. This analysis method breaks down polymers into monomers and, in the process, also breaks down any sulfate and acetyl side chains. Monosaccharide standards were treated in a parallel fashion and used for calibration of HPAEC-PAD.

FTIR spectroscopy

FTIR spectra were recorded with a Bruker VERTEX 70 FTIR spectrophotometer (4000 to 400 cm−1, 4 cm−1 resolution) working in attenuated total reflectance (ATR) mode. One droplet of skate jelly was carefully placed on the ATR crystal and allowed to dry for 30 min. Then, we recorded the FTIR spectrum.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Khan and J. Tang for technical assistance, C. Luer for the AoL jelly sample of the bonnethead shark, and L. Cox for creating the illustrations in Fig. 1. We thank Bornstein Seafoods for allowing us to collect AoL jelly in their packing plants and for donating specimens. J.S. thanks the library staff of the Observatoire Océanographique (Villefranche-sur-mer, France) for their consideration while he was doing background research. Funding: This work was funded by NSF CAREER Award DMR-1150630 (electrical characterization) to M.R., Office of Naval Research Award N00014-14-1-0724 (materials characterization) to M.R., and NIH grant RO1-GM090049 to C.T.A. Part of this work was conducted at the Washington Nanofabrication Facility/Molecular Analysis Facility, a member of the NSF National Nanotechnology Infrastructure Network. Author contributions: E.E.J. designed and performed the electrical measurements and analyzed the data with M.R. P.H. performed the FTIR measurements. Y.D. performed the elemental analysis. J.S., M.J.R., and C.T.A. provided the samples and conducted background research. M.R. coordinated the work. E.E.J., J.S., and M.R. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all the authors. All authors revised the manuscript. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/2/5/e1600112/DC1

fig. S1. Collection of AoL jelly.

fig. S2. TGA of AoL jelly.

fig. S3. Cross-species consistency of results.

fig. S4. Control experiments on Nafion.

table S1. Elemental analysis of AoL jelly as analyzed by Intertek Pharmaceutical.

table S2. Room-temperature proton conductivities of Nafion and known biopolymers.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.S. Lorenzini, Osservazioni Intorno Alle Torpedini (Per l’Onofri, Firenze, 1678). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray R. W., The response of the ampullae of Lorenzini of elasmobranchs to electrical stimulation. J. Exp. Biol. 39, 119–128 (1962). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Camperi M., Tricas T. C., Brown B. R., From morphology to neural information: The electric sense of the skate. PLOS Comput. Biol. 3, e113 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.N. Sperelakis, Cell Physiology Sourcebook: Essentials of Membrane Biophysics (Elsevier/AP, Amsterdam, ed. 4, 2012), p. xxvi, 970 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalmijn A. J., Electric and magnetic field detection in elasmobranch fishes. Science 218, 916–918 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waltman B., Electrical properties and fine structure of the ampullary canals of Lorenzini. Acta Physiol. Scand. Suppl. 264, 1–60 (1966). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fields R. D., The shark’s electric sense. Sci. Am. 297, 74–81 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown B. R., Neurophysiology: Sensing temperature without ion channels. Nature 421, 495 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown B. R., Temperature response in electrosensors and thermal voltages in electrolytes. J. Biol. Phys. 36, 121–134 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fields R. D., Fields K. D., Fields M. C., Semiconductor gel in shark sense organs? Neurosci. Lett. 426, 166–170 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown B. R., Hutchison J. C., Hughes M. E., Kellogg D. R., Murray R. W., Electrical characterization of gel collected from shark electrosensors. Phys. Rev. E 65, 061903 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhong C., Deng Y., Roudsari A. F., Kapetanovic A., Anantram M. P., Rolandi M., A polysaccharide bioprotonic field-effect transistor. Nat. Commun. 2, 476 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deng Y., Josberger E., Jin J., Rousdari A. F., Helms B. A., Zhong C., Anantram M., Rolandi M., H+-type and OH−-type biological protonic semiconductors and complementary devices. Sci. Rep. 3, 2481 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Josberger E. E., Deng Y., Sun W., Kautz R., Rolandi M., Two-terminal protonic devices with synaptic-like short-term depression and device memory. Adv. Mater. 26, 4986–4990 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hemmatian Z., Miyake T., Deng Y., Josberger E. E., Keene S., Kautz R., Zhong C., Jin J., Rolandi M., Taking electrons out of bioelectronics: Bioprotonic memories, transistors, and enzyme logic. J. Mater. Chem. C 3, 6407–6412 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wünsche J., Deng Y., Kumar P., Di Mauro E., Josberger E., Sayago J., Pezzella A., Soavi F., Cicoira F., Rolandi M., Santato C., Protonic and electronic transport in hydrated thin films of the pigment eumelanin. Chem. Mater. 27, 436–442 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bardelmeyer G. H., Electrical conduction in hydrated collagen. I. Conductivity mechanisms. Biopolymers 12, 2289–2302 (1973). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown B. R., Hughes M. E., Russo C., Infrastructure in the electric sense: Admittance data from shark hydrogels. J. Comp. Physiol. A 191, 115–123 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katsaounis A., Balomenou S., Tsiplakides D., Brosda S., Neophytides S., Vayenas C. G., Proton tunneling-induced bistability, oscillations and enhanced performance of PEM fuel cells. Appl. Catal. B 56, 251–258 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rienecker S. B., Mostert A. B., Schenk G., Hanson G. R., Meredith P., Heavy water as a probe of the free radical nature and electrical conductivity of melanin. J. Phys. Chem. B 119, 14994–15000 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sone Y., Ekdunge P., Simonsson D., Proton conductivity of Nafion 117 as measured by a four-electrode AC impedance method. J. Electrochem. Soc. 143, 1254–1259 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 22. S. M. Sze, K. K. Ng, Physics of Semiconductor Devices (John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amdursky N., Wang X., Meredith P., Bradley D. D., Stevens M. M., Long-range proton conduction across free-standing serum albumin mats. Adv. Mater. 28, 2692–2698 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doyle J., The ‘Lorenzan sulphates’. A new group of vertebrate mucopolysaccharides. Biochem. J. 103, 325–330 (1967). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Longas M. O., Breitweiser K. O., Sulfate composition of glycosaminoglycans determined by infrared spectroscopy. Anal. Biochem. 192, 193–196 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y., Go E. P., Jiang H., Desaire H., A novel mass spectrometric method to distinguish isobaric monosaccharides that are phosphorylated or sulfated using ion-pairing reagents. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 16, 1827–1839 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagle J. F., Mille M., Morowitz H. J., Theory of hydrogen bonded chains in bioenergetics. J. Chem. Phys. 72, 3959 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ordinario D. D., Phan L., Walkup W. G. IV, Jocson J.-M., Karshalev E., Hüsken N., Gorodetsky A. A., Bulk protonic conductivity in a cephalopod structural protein. Nat. Chem. 6, 596–602 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rolandi M., Bioelectronics: A positive future for squid proteins. Nat. Chem. 6, 563–564 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/2/5/e1600112/DC1

fig. S1. Collection of AoL jelly.

fig. S2. TGA of AoL jelly.

fig. S3. Cross-species consistency of results.

fig. S4. Control experiments on Nafion.

table S1. Elemental analysis of AoL jelly as analyzed by Intertek Pharmaceutical.

table S2. Room-temperature proton conductivities of Nafion and known biopolymers.