Abstract

Assess whether receipt of tailored printouts generated by the Cancer Risk Intake System (CRIS) – a touch-screen computer program that collects data from patients and generates printouts for patients and physicians – results in more reported patient-provider discussions about colorectal cancer (CRC) risk and screening than receipt of non-tailored information.

Cluster-randomized trial, randomized by physician, with data collected via CRIS prior to visit and 2-week follow-up telephone survey among 623 patients.

Patients aged 25–75 with upcoming primary-care visits and eligible for, but currently non-adherent to CRC screening guidelines.

Patient-reported discussions with providers about CRC risk and testing.

Tailored recipients were more likely to report patient-physician discussions about personal and familial risk, stool testing, and colonoscopy (all p < 0.05). Tailored recipients were more likely to report discussions of: chances of getting cancer (+ 10%); family history (+ 15%); stool testing (+ 9%); and colonoscopy (+ 8%) (all p < 0.05).

CRIS is a promising strategy for facilitating discussions about testing in primary-care settings.

Keywords: Colorectal neoplasms, Mass screening, Physician-patient relations, Health behavior, Tailoring

Highlights

-

•

Cancer Risk Intake System (CRIS) intervention is a touch-screen computer program.

-

•

Patients use CRIS to input CRC risk factor data before primary care appointments.

-

•

CRIS generates tailored printouts with guideline-based screening recommendations.

-

•

Our randomized trial compared receipt of CRIS tailored v. non-tailored printouts.

-

•

CRIS tailored group reported more patient-MD discussion of CRC risk and testing.

1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) testing can prevent mortality (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2008) but participation in testing is too low (Smith et al., 2014, Holden et al., 2010). Patients have limited knowledge about need for and benefits of testing (Guerra et al., 2005, Doubeni et al., 2010, Beydoun and Beydoun, 2008). Physicians' recommendations are strong predictors of testing (Sarfaty and Wender, 2007, Wee et al., 2005, Klabunde et al., 2005, O'Malley et al., 2004) but recommendation rates remain suboptimal.

Providers may have difficulty determining what type and schedule of testing is appropriate for patients' particular risk levels, because family and personal risk factors (e.g., number, size, and histology of polyps or family members' ages at diagnosis) (Winawer et al., 2003) are not routinely documented in patients' charts. This may be especially true for patients whose risk levels warrant screening before age 50. There is little information about how many of these younger individuals would benefit from screening, what type they should have, or prevalence of physician recommendations for screening. However, there is reason to believe that screening among younger at-risk individuals is lower than among those over 50. 2010 National Health Interview data showed colonoscopy rate among first-degree relatives ages 40 to 49 (38.3%) was about half of those 50 and older (69.7%) (Tsai et al., 2015). Collecting and evaluating risk information during an office visit can be too time-consuming and complicated (Burke, 2005, Suther and Goodson, 2003) for routine practice.

We developed the Cancer Risk Intake System (CRIS) — a touch-screen program that collects data prior to office visits and generates printouts for patients and physicians tailored on: personal and familial risk factors; guideline-based recommendations for test modality, age at initiation, and schedule; and patient concerns about testing. By providing an individually tailored intervention at the point of care delivery, CRIS was meant to be a helpful and unobtrusive adjunct to clinical care.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Overview

In this cluster-randomized trial, physicians were randomly assigned to receive CRIS-tailored printouts outlining patients' specific risk factors, guideline-based testing options, and concerns about testing, or a standard chart prompt for patients ≥ 50 and not recently screened. Based on assignment of their physicians, patients used CRIS and received tailored (n = 329) or non-tailored (n = 322) printouts. To mask the purpose of CRIS for the non-tailored comparison group, data collection included questions about multiple cancers, not only CRC. Overall goal of the study was compare screening outcomes between the CRIS tailored and non-tailored groups as well as a third group that did not use CRIS and received no contact. However, as a mechanism for understanding how the CRIS tailored intervention might ultimately increase screening, we also assessed whether it prompted patient-provider discussions. Here we report results from patient telephone surveys conducted with 623 patients from the tailored and non-tailored groups two weeks after the office visit during which they used the CRIS. Data were collected by Research Assistants, blinded to participants' random assignment.

2.2. Setting

The study, approved by the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Institutional Review Board and registered on clinicaltrials.gov, enrolled insured patients seen in the general internal medicine faculty clinic and the family medicine faculty clinic at the University of Texas Southwestern (UTSW) Medical Center. A UTSW electronic medical records system administrator developed a query to identify potentially eligible patients with upcoming appointments.

2.3. Eligibility criteria

We sought to enroll patients who were eligible for, but not adherent to, CRC testing based on national guidelines (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2008, Smith et al., 2014, Levin et al., 2008). We invited patients younger than 50 because CRIS algorithms identify those whose risks warrant early testing due to personal history of polyps or inflammatory bowel diseases, or family history of polyps or cancer. For lower age limit, we selected 25 — the age by which the National Comprehensive Cancer Network at the time of study initiation recommended beginning colonoscopy among carriers of mutations for the Lynch syndrome, the most common hereditary cancer syndrome (Lynch et al., 2004). For patients < 50, research assistants (RAs) conducted screening during recruitment calls to identify potentially eligible participants with CRC family history, personal history of inflammatory bowel disease, or adenomatous polyps. We asked about these risk factors during this phone screening process because they are not reliably collected and entered into patients' electronic medical records. We selected 75 as the upper age for inclusion(U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2002) and excluded those who had no telephone access and were unable to speak or read English.

2.4. Study design

The study has been explained in detail elsewhere (Skinner et al., 2015a) and is summarized here. Physician was the unit of random assignment. We used the SAS PROC Plan (SAS, 2014) procedure to randomly assign physicians either to CRIS-tailored or non-tailored group using permuted-block randomization with varying block sizes; their patients were therefore pre-identified as CRIS-tailored or non-tailored group members before they were invited (Those identified as members of a no-contact control group were, by definition, never contacted and are not included in this report of outcomes from the telephone survey). Identified patients with upcoming appointments (n = 10,216) received letters signed by the clinic medical director saying they “might be invited” for participation in a “study of beliefs and practices about cancer prevention and early detection.” After one week during which 96 opted out of contact, research assistants (RAs) called patients to explain the study, verify eligibility and, if patients agreed, arrange in-person meetings 30 min before appointments. Of 2989 potentially eligible patients reached and invited, 1032 agreed to participate and 935 arrived in time to use CRIS.

Research Assistants (RA) met patients in the clinic waiting room to obtain consent and facilitate use of the CRIS program on a touch-screen tablet computer. After completion, patients gave the tablet back to the RA, who connected it with a printer to generate the printouts. RAs handed the patient's printout directly to the patient and placed the physician's printout with the patient's demographic sheet — the only piece of paper used for the clinic encounter.

CRIS collected demographics, personal history including previous testing, detailed family history, and concerns about testing, then used these data to determine first whether any testing was currently needed. Of the 935 who completed the CRIS, 651 were in need of testing. For these, CRIS determined risk-appropriate testing option(s) and generated the tailored or non-tailored printouts. RAs conducted telephone interviews with 95.7% (623/651) of participants within 2 weeks of the office visit. Participants received a $10 gift card for completing the CRIS and $15 for completing the 2-week telephone interview.

2.5. Interventions and measures

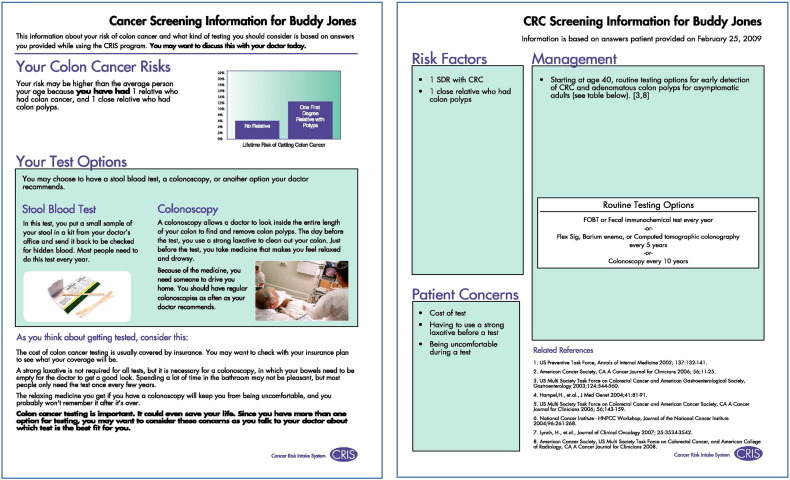

Sample CRIS-tailored printouts appear in Fig. 1. Each includes: summary of patient's CRC risks, appropriate test(s) based on self-reported risk factors, and concerns about testing. Consistent with health behavior theory (Skinner et al., 2015b), the patient's version portrays elevated risk factors with a graphic, includes a statement about testing benefits along with which type of testing is guideline-based, and includes brief messages designed to address concerns. Physicians' printouts list risk factors, guideline-based testing option(s), and the patient's concerns. Because data entered into the program are only as accurate as users' knowledge and memory, a statement explains the information is based on patient report on the specific date.

Fig. 1.

Sample printouts (patient sample on left and physician sample on right).

Patients in the non-tailored group received text from the American Cancer Society brochure (about multiple types of screening) inserted into a format similar to the tailored printouts; their physicians received the UT Southwestern “best practice” electronic prompt for patients 50 and older with no documentation of CRC screening.

To assess topics of discussion during the visit, Research Assistants read: These next questions are about what you and your doctor talked about during your visit. I′ll read a list. You probably didn't talk about all of these, but you may have talked about some. For each please answer yes, no, or you can't remember. They then read the topics shown in Table 2, which lists percentages answering “yes” to each.

Table 2.

Comparison of patient discussions of cancer risk and testing with their provider.

| Discussion topic | Tailored n = 314 % |

Non-tailored n = 309 % |

Odds ratio (95% CI) |

p-Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chances of getting cancer | 27 | 17 | 1.9 (1.2–2.9) | 0.004 |

| Family history of cancer | 40 | 25 | 1.9 (1.1–3.1) | 0.014 |

| Meeting genetic counselor | 5 | 4 | 1.4 (0.6–3.0) | 0.447 |

| Having a stool blood test | 30 | 21 | 1.6 (1.1–2.3) | 0.011 |

| Having a flexible sigmoidoscopy | 18 | 15 | 1.3 (0.8–2.1) | 0.307 |

| Having a colonoscopy | 74 | 66 | 1.5 (1.0–2.2) | 0.025 |

| Having a CT colonography | 9 | 5 | 1.8 (0.9–3.4) | 0.066 |

| Having a barium enema | 6 | 4 | 1.7 (0.8–3.6) | 0.177 |

CI: Confidence interval.

Non-tailored group is the reference group. Clinical provider is included in model as a random cluster effect.

2.6. Statistical analysis

To test differences in reported discussions about cancer risk and testing, baseline variables were analyzed using generalized linear mixed models including physician as a random cluster effect. The final analytical sample was 623 patients (n = 314 tailored and n = 309 non-tailored).

3. Results

In the tailored and non-tailored groups, participants were similarly and primarily non-Hispanic White (62% and 67.7%, respectively), and female (62.3% and 67.1%, respectively). See Table 1. In both groups, just over half had at least four years of college (50.2% and 53.1%, respectively). Mean age in tailored group was slightly younger (57.5 v. 59.1 years; p = 0.038). Numbers of patients under age 50 who, according to their reported risk factors were due for screening, were similarly small in the tailored (n = 35) and non-tailored (n = 22) groups (10.6% v. 6.8%; p = .086) (Skinner et al., 2015a). Unemployment was lower in the tailored group (27.1% v. 40.7%, p = .0003).

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics by tailored and non-tailored groups.

| Tailored n = 329 n (%) |

Non-tailored n = 322 n (%) |

p-Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (± SD) | 57.5 (± 8.6) | 59.1 (± 7.9) | 0.038 |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.529 | ||

| Hispanic | 31 (9.4) | 26 (8.1) | |

| NH White | 205 (62.3) | 218 (67.7) | |

| NH Black | 76 (23.1) | 63 (19.6) | |

| Asian/Indian/PI | 13 (4.0) | 10 (3.1) | |

| Other/Refused | 4 (1.2) | 5 (1.6) | |

| Gender | 0.797 | ||

| Female | 205 (62.3) | 216 (67.1) | |

| Male | 124 (37.7) | 106 (32.9) | |

| Educationb | 0.452 | ||

| < 4 years of college | 163 (49.5) | 151 (46.9) | |

| ≥ 4 years of college | 165 (50.2) | 171 (53.1) | |

| Employmentb | 0.0003 | ||

| Full or part-time | 239 (72.6) | 191 (59.3) | |

| Unemployed | 89 (27.1) | 131 (40.7) |

SD: Standard Deviation; NH: Non-Hispanic; PI: Pacific Islander.

Clinical provider is included as a random cluster effect in the model.

One patient refused education (tailored group); one patient refused employment (tailored group).

As shown in Table 2, there were significant between-group differences in patient-reported discussions with providers. Tailored recipients were more likely to report discussions about getting cancer (p = .004), family history (p = .014), and having a stool test (p = .011) and colonoscopy (p = .025).

4. Conclusions

4.1. Discussion

Patients in the CRIS-tailored group reported more discussion about CRC risk and testing with their physicians during the office visit. The tailored patient printed materials, combined with the tailored physician's version (in contrast to only the electronic “best practice” prompt received by physicians in the non-tailored group) may have provided more guidance about topics to discuss during the visit. Particularly robust increases were noted for discussion of family history of cancer, as well as chances of getting cancer.

Discussion alone does not automatically translate into recommendation for or completion of guideline-based testing, but such discussions have been shown to predict participation in screening (Sohler et al., 2015). Recent studies have shown that that use of a narrative interactive computer program about CRC screening before a visit led to more discussion about screening than receipt of a non-tailored brochure (Christy et al., 2013), and a physician-patient intervention was more effective than a physician-only intervention for increasing rates of CRC screening discussion (Dolan et al., 2015). Findings are also consistent with a previous quasi-experimental (pre-post) pilot test conducted with an earlier version of CRIS (Skinner et al., 2005) in which patient-provider discussions increased after CRIS and its tailored printouts were introduced into the clinic, compared to before. However, because that study did not compare a tailored v. non-tailored printout, it is only now through the randomized trial that we are able to determine that it was the tailored content, rather than the experience of using CRIS and receiving any printed materials, that seem to have facilitated the discussions.

4.2. Limitations

Data reported here are limited to the 623 patients who agreed to participate, arrived in time to use CRIS for data collection prior to their appointments, and completed the 2-week telephone survey. Outcome for those who, for whatever reason, did not participate when invited, may have differed.

Although previous research has demonstrated reasonable accuracy in reporting family history (Murff et al., 2004) and CRC screening (Baier et al., 2000), to the extent that patients were mistaken about CRIS responses, accuracy of the resulting guideline recommendations could have been compromised. Our findings are only applicable to patients and physicians receiving reports based on risk factors reported by patients, just prior to an office visit.

The fact that patient-physician discussions were self-reported is also a limitation of our findings. Self-reports, while often assessed in intervention trials (Skinner et al., 2015b, Christy et al., 2013), do not always equate with observed discussions (Carroll et al., 2008). Therefore, we can only conclude that more patients in the tailored group perceived and reported discussions than those in the non-tailored group. Also, because the items literally measured self-report of topics discussed during the visit, we must note that the reported discussion may or may not have included a screening recommendation.

Finally, data from this trial do not tell us what prompted reported discussions — tailored information to the patient, the physician, or both? We know that the print outs were given to all patients who used CRIS and to physicians in the tailored group but there was likely variation in how much attention each gave to his or her printout. More study is needed to determine the mechanism of action.

5. Conclusion

Patients' use of CRIS and they and their physicians' receipt of tailored printouts led to more reported discussion about CRC risk and screening than patients receiving a non-tailored print out following CRIS use and their physicians getting a standard chart prompt. CRIS is a promising strategy for facilitating discussions about risk-based testing in primary-care settings. Programs like CRIS, with ability to collect risk information and particular patient concerns, may become increasingly important with the advent of more personalized medicine and inherently complex screening decisions.

Role of funding

This study was funded by NCI RO1 CA1223301. The funding source had no involvement in the conduct of the research and/or preparation of the article; in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Conflict of interest

No conflicts of interest have been declared by the authors.

Transparency document

Transparency document.

Acknowledgments

-

1.

There were no contributors to the manuscript other than the authors listed.

-

2.

This paper has not been presented at a conference.

Footnotes

The Transparency document related to this article can be found, in the online version.

References

- Baier M., Calonge N., Cutter G. Validity of self-reported colorectal cancer screening behavior. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2000;9(2):229–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beydoun H.A., Beydoun M.A. Predictors of colorectal cancer screening behaviors among average-risk older adults in the United States. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19(4):339–359. doi: 10.1007/s10552-007-9100-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke W. Taking family history seriously. Ann. Intern. Med. 2005;143(5):388–389. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-5-200509060-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll J.K., Fiscella K., Meldrum S.C. Clinician-patient communication about physical activity in an underserved population. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2008;21(2):118–127. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2008.02.070117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christy S.M., Perkins S.M., Tong Y. Promoting colorectal cancer screening discussion: a randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013;44(4):325–329. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan N.C., Ramirez-Zohfeld V., Rademaker A.W. The effectiveness of a physician-only and physician-patient intervention on colorectal cancer screening discussions between providers and African American and Latino patients. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2015;30(12):1780–1787. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3381-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doubeni C.A., Laiyemo A.O., Young A.C. Primary care, economic barriers to health care, and use of colorectal cancer screening tests among Medicare enrollees over time. Ann. Fam. Med. 2010;8(4):299–307. doi: 10.1370/afm.1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra C.E., Dominguez F., Shea J.A., Guerra C.E., Dominguez F., Shea J.A. Literacy and knowledge, attitudes, and behavior about colorectal cancer screening. J. Health Commun. 2005;10(7):651–663. doi: 10.1080/10810730500267720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden D.J., Jonas D.E., Porterfield D.S., Reuland D., Harris R. Systematic review: enhancing the use and quality of colorectal cancer screening. Ann. Intern. Med. 2010;152(10):668–676. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-10-201005180-00239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klabunde C.N., Vernon S.W., Nadel M.R., Breen N., Seeff L.C., Brown M.L. Barriers to colorectal cancer screening: a comparison of reports from primary care physicians and average risk adults. Med. Care. 2005;43:939–944. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000173599.67470.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin B., Lieberman D.A., McFarland B. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US multi-society task force on colorectal cancer, and the American College of Radiology. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(5):1570–1595. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch H.T., Shaw T.G., Lynch J.F. Inherited predisposition to cancer: a historical overview. Am. J. Med. Genet. C: Semin. Med. Genet. 2004;129C(1):5–22. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murff H.J., Spigel D.R., Syngal S. Does this patient have a family history of cancer? An evidence-based analysis of the accuracy of family cancer history. JAMA. 2004;292(12):1480–1489. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.12.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Malley A.S., Beaton E., Yabroff K.R., Abramson R., Mandelblatt J. Patient and provider barriers to colorectal cancer screening in the primary care safety-net. Prev. Med. 2004;39(1):56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarfaty M., Wender R. How to increase colorectal cancer screening rates in practice. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2007;57(6):354–366. doi: 10.3322/CA.57.6.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS . SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, NC: 2014. Stat User's Guide. Version 9.4. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner C.S., Halm E.A., Bishop W.P. Impact of risk assessment and tailored versus nontailored risk information on colorectal cancer testing in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2015;24(10):1523–1530. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner C.S., Rawl S.M., Moser B.K. Impact of the cancer risk intake system on patient-clinician discussions of tamoxifen, genetic counseling, and colonoscopy. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2005;20(4):360–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40115.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner C.S., Tiro J.A., Champion V.L. The Health Belief Model. In: Glanz K., Rimer B.K., Viswanath K., editors. Health Behavior. Theory, Research, and Practice. fifth ed. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2015. pp. 75–94. [Google Scholar]

- Smith R.A., Manassaram-Baptiste D., Brooks D. Cancer screening in the United States, 2014: a review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and current issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2014;64(1):30–51. doi: 10.3322/caac.21212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohler N.L., Jerant A., Franks P. Socio-psychological factors in the expanded health belief model and subsequent colorectal cancer screening. Patient Educ. Couns. 2015;98(7):901–907. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suther S., Goodson P. Barriers to the provision of genetic services by primary care physicians: a systematic review of the literature. Genetics in Medicine. 2003;5(2):70–76. doi: 10.1097/01.GIM.0000055201.16487.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai M.H., Xirasagar S., Li Y.J., de Groen P.C. Colonoscopy screening among US adults aged 40 or older with a family history of colorectal cancer. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2015;12 doi: 10.5888/pcd12.140533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Screening for colorectal cancer: recommendation and rationale. Ann. Intern. Med. 2002;137(2):129–131. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-2-200207160-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Screening for colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2008;149(9):627–638. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-9-200811040-00243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wee C.C., McCarthy E.P., Phillips R.S. Factors associated with colon cancer screening: the role of patient factors and physician counseling. Prev. Med. 2005;41(1):23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winawer S., Fletcher R., Rex D. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance: clinical guidelines and rationale-update based on new evidence. Gastroenterology. 2003;124(2):544–560. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Transparency document.