Abstract

Purpose

The care of cancer patients involves collaboration among health care professionals, patients, and family caregivers. As health care has evolved, more complex and challenging care is provided in the home, usually with the support of family members or friends. The aim of the study was to examine perceived needs regarding the psychosocial tasks of caregiving as reported by patients and caregivers. We also evaluated the association of demographic and clinical variables with self-reported caregiving needs.

Methods

Convenience samples of 100 cancer patients and 100 family caregivers were recruited in outpatient medical and radiation oncology waiting areas - the patients and caregivers were not matched dyads. Both groups completed a survey about their perceptions of caregiving tasks, including how difficult the tasks were for them to do. Demographic information was also provided by participants.

Results

Caregivers reported providing more help in dealing with feelings than patients endorsed needing. Caregivers were also more likely than patients to report the psychosocial aspects of caregiving were more difficult for them. Lastly, caregivers were more likely to report helping with logistical issues in comparison with patients expressing this need. Race, length of time since diagnosis, and age were associated with patients’ expressed needs, while only number of hours spent providing care was associated with the caregivers’ reporting of care activities.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that patients may underestimate how difficult caregivers perceive the psychosocial aspects of caregiving to be. Also, it seems that caregivers tend to take on the psychosocial aspects of caregiving, although patients don’t tend to report this need. Caregiving needs were only minimally associated with demographic variables, as was participation in caregiving tasks.

Keywords: Cancer, Family Caregiving, Psychosocial Needs, Patients’ Perceptions, Caregivers’ Perceptions

The care of cancer patients involves multiple providers that include health care professionals and family caregivers. Of the estimated 1,479,350 cancer patients newly diagnosed each year, most will rely on informal or family caregivers to assist them [1]. Family caregivers are defined as those persons who provide uncompensated care to the patient. They tend to be female, younger than the patient, employed, and often not living in the same household as the patient [2]. The most common relationship of the caregiver to the care receiver is an adult child assisting an elderly parent, followed by a spouse, most often an elderly wife or husband [3, 4]. In a survey of over 600 caregivers, the average amount of time spent providing care was 8.3 hours per day, with 25% of caregivers providing care for more than 16 hours per day [5].

Tasks usually performed by caregivers of cancer patients include assisting with activities of daily living, watching for side effects of treatment, managing symptoms (pain, nausea, fatigue), and administering medication [6]. Besides the provision of direct care, caregiving tasks include indirect care, such as comfort care, transportation support, and assistance with information-seeking [7]. In the previously cited survey of caregivers, 52% reported providing emotional support as part of their caregiving, while 46% reported providing logistical or tangible support [5]. Logistical tasks, including coordination of care, often fall to the family caregiver, and these tasks have been identified as the most time-consuming and most difficult to perform [8].

The financial impact on the patient and family caregiver is multifaceted and may vary by country. Caregivers are likely to report lost hours from work, especially at the time of diagnosis, which can affect their income [9]. The tasks of managing insurance paperwork and bills are borne by both patients and their caregivers. A significant portion of the 1.5 million adults in the U.S. who declare bankruptcy annually attribute their financial difficulties to medical bills [10]. Predictors of financial burden and diminished quality of life for caregivers include the caregiver’s limited income or poor health, extended time in the caregiver role, and the care recipient’s poor performance status [11].

Addressing the emotional and non-medical needs of both the cancer patient and the caregiver is an essential part of preparing families for the caregiving experience. Mastering the tasks required of a family caregiver is a challenge. The perceived burden of cancer and degree of distress are indicators of how well or how poorly caregivers have been prepared to take on their role [12, 13]. Caregivers feeling ill-prepared for their roles and responsibilities have reported increased mood disturbance, such as higher levels of depression, anxiety, and guilt [14, 15, 16]. Family caregivers experiencing role overload in providing cancer care report that the stress of caregiving leads to an exacerbation of multiple secondary stressors, including poor family support and increased financial stress [17]. Factors that improve the caregiving experience include increased social support and a better caregiver-patient relationship [18].

The experience of family caregiving gives rise to psychosocial needs that can vary by the patient’s stage of survival, defined as acute survival, extended survival, and permanent survival [19]. Throughout survivorship or at cancer recurrence, opportunities arise for healthcare providers to reassess the need for further psychosocial education and support for both the patient and caregiver. The informational needs of cancer survivors and caregivers are varied. Beyond information about their physical health, including side effects of treatment and strategies for health promotion, survivors have been found to need information about interpersonal and emotional issues [20]. A minority of caregivers report that their practical and informational needs are met [21], while caregivers who are younger, of minority race/ethnicity, and those with more comorbid health problems have reported greater informational needs [20].

Potter et al. [22] previously published data from the study described here concerning the care activities cancer patients and family caregivers perform in the home, their perceptions of the difficulty of caregiving tasks, and their need for information. Findings from the study indicated that cancer caregivers need more nursing support, specifically to learn caregiving skills. Differences in the type of activities patients and caregivers perform, the perceived difficulty of caregiving tasks, and the expressed needs for assistance strongly suggest the need for a thorough learning needs assessment and tailored educational interventions. The study also revealed important differences in the desire for information and support. Younger patients, recently diagnosed patients (12 months or less), and caregivers who spent less than 40 hours per week in this role all reported a greater desire for information or assistance.

In this paper, we focus on the emotional and psychosocial tasks of caregiving – particularly dealing with feelings about having cancer, dealing with insurance and bills, and helping with nonmedical problems - as endorsed by patients and family caregivers in the study described above [22]. This focus was chosen given the interesting qualitative feedback received from both patients and caregivers in the larger study and the lack of existing literature addressing this aspect of caregiving. The specific aims were to examine and compare the responses of family caregivers and cancer patients to questions about the above noted aspects of caregiving. We also examined the association of demographic and clinical variables with self-reported needs relevant to caregiving.

Methods

This survey study comparing perceptions of caregiving needs was conducted at a large National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer center in the midwestern United States using convenience samples of cancer patients and family caregivers of cancer patients. The Human Research Protection Office of the associated university approved the study and all subjects gave informed consent before participating.

Potential participants were recruited while visiting the cancer center’s outpatient medical oncology and radiation oncology clinic waiting areas. Members of the research team manned a display table in the waiting areas where informational fliers were posted explaining the study. Interested participants were self-selected and received the study materials at the display table. Participants were recruited over a 3 month period between October 2007 and January 2008. Eligible patients had been diagnosed with cancer and were currently receiving chemotherapy, biotherapy, or radiation therapy; were age 18 or older; and spoke English as their primary language. Eligible caregivers identified themselves as friends or family members who provided a cancer patient routine care and support in the home. In addition, caregivers were also aged 18 or older and spoke English as their primary language. A convenience sample of 100 cancer patients and 100 family caregivers was recruited. Patients who participated in this study did not necessarily have their own caregivers participate, and vice versa for participating caregivers; this was not a study of patient-caregiver dyads.

Instruments

There were no established tools designed to measure cancer patients’ or caregivers’ perceptions of their learning needs (desire for information and support) with respect to the tasks of caregiving. The research team (nurses, social worker, and psychologist) used clinical experience and review of the research literature to develop an instrument of 16 common physical and psychosocial caregiving activities. The surveys were designed for a 7th grade reading level. Because of the interest in assessing learning needs, a specific question was included regarding whether more information was needed about each task. Both patient and caregiver versions of the instrument were developed, with slight variations in wording (see Table 1). Patients were asked to identify activities they do independently, activities for which they need assistance, and activities they would like to know more about. Caregivers were asked to identify those activities they do for the person with cancer, activities that are difficult for them to accomplish, and activities they would like to know more about. Participants could check any or all three options for each activity. The instrument also included open-ended questions to determine patients’ perceptions of activities that were most difficult to do for themselves and caregivers’ perceptions of activities that were most difficult to do for the person with cancer. Each group also had the opportunity to identify nonmedical problems that were a challenge for them, as well as the chance to endorse whether or not they wanted information about how to cope with their own needs and feelings.

Table 1.

Relevant Items from Assessment Tool

| Caregiving Domains | Patient Version | Caregiver Version |

|---|---|---|

| Feelings about Having Cancer | Deal with feelings about having cancer | Help the person deal with feelings about having cancer |

| Insurance and Medical Bills | Deal with insurance and medical bills | Deal with insurance and medical bills |

| Non-Medical Problems | Deal with other non-medical problems | Help with other non-medical problems |

| Response Options | ||

| Check all activities that you do on your own. | Check all activities that you do for the person with cancer. | |

| Check all activities that you need help to perform. | Check activities that are difficult for you to do or perform. | |

| Check all activities that you would like to know more about. | Check all activities that you would like to know more about. | |

| Open-Ended Questions | ||

| What activity is the hardest for you to do for yourself? | What activity is the hardest for you to do for your loved one? | |

| What activity do you think is the hardest for those who take care of you? | What activity do you think is the hardest for your loved one to do for himself or herself? | |

| Would you like information to help with your own needs and feelings? | Would you like information to help with your own needs and feelings? | |

| If you have comments or other needs not on this survey, please write them below. | If you have comments or other needs not on this survey, please write them below. |

An earlier article [22] described the general learning needs identified with this survey, while the present article focuses specifically on psychosocial aspects of caregiving. Three of the activities listed in the assessment tool are the focus of this paper - coping with feelings about having cancer, helping with insurance and medical bills, and dealing with other non-medical problems.

Patients completed a demographics form that asked their type of cancer, stage, and length of time since their cancer diagnosis. Caregivers were asked to identify what type of cancer affected the person they cared for, the number of hours per week they provided care, and the length of time for which they had been caregivers. Both patients and caregivers were asked to rate their own level of health on a 5-point Likert scale, with 1 representing “poor” health and 5 representing “excellent” health.

In the analysis of data, patient and caregiver demographics were examined independently since the subjects were not matched, and means or percentages were tabulated. Responses to the questions relating to caregiving activities were calculated as frequencies and plotted to describe activities perceived as difficult to perform or requiring assistance, and activities for which patients and caregivers desired further information. Chi square, Fisher’s exact test or ANOVA were computed to examine relationships between demographic characteristics and the caregiving activities perceived as difficult (caregivers) or for which they needed help (patients) or for which they needed more information (caregivers and patients). For the purpose of analysis, some variables were re-categorized based on clinical significance and data properties in order to maximize power. For example, rather than reporting each grade of cancer, grades 1 through 3 were combined as “lower grade” and compared with grade 4 and with “unsure”. Age was classified into two groups: 1) younger than 65 years old and 2) older than 65 years old. All the tests were two-sided and significance level was set at 0.05. SAS 9.1.3 was used for major statistical calculations (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Qualitative responses were reviewed by the first two authors using thematic content analysis, a method for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns or themes within data (23). Thematic analysis was applied inductively in this study to identify common themes among the responses.

Results

Participants’ demographics are presented in Table 2 (patients’ information) and Table 3 (caregivers’ information). Because of our sample size, numbers and percentages are identical; therefore only percentages are reported in the text. Our samples of patients and caregivers were predominantly female and Caucasian. The majority of caregivers were spouses and about half of the caregivers were working full- or part-time. The distribution of types of cancer was different for the patient and caregiver groups, consistent with the two groups not being related. Time since diagnosis was divided into 3 groups, roughly approximating stages of survivorship: 1–12 months (which would include most treatment activity), 13–36 months (representing early survivorship), and 37 months or more (representing later survivorship). While the median length of time since diagnosis was 12.0 months, most cancer patients (57%) fell into the first group. Likewise, duration of caregiving was divided into the same time frames. The median duration of caregiving was 8.5 months, and most caregivers (67%) fell into the first group (1–12 months).

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics of Patients

| Characteristic | N (with sample size, N approximates % unless noted) |

|---|---|

| Age (range = 18–85 years) | Mean = 57.2, SD= 14.3 |

| Time since Diagnosis1 (range = 2–348 months) | Median = 12.0 mos. |

| 1–12 months | 51 (57%) |

| 13–36 months | 20 (22%) |

| 37 months or more | 19 (21%) |

| Sex2: | |

| Female | 65 |

| Male | 34 |

| Race: | |

| White | 80 |

| Other | 20 |

| Education: | |

| Some College | 73 |

| No College | 27 |

| Employment: | |

| Full or Part-Time Work | 20 |

| Retired | 39 |

| Disabled, Unemployed | 26 |

| Other | 15 |

| Insurance Status: | |

| Yes | 83 |

| No | 3 |

| Missing data | 14 |

| Type of Cancer: | |

| Hematologic | 19 |

| Breast | 18 |

| Colorectal | 11 |

| Lung | 11 |

| Other | 41 |

| Stage of Cancer3: | |

| 1, 2, or 3 | 26 (28%) |

| 4 | 21 (23%) |

| Unsure | 46 (49%) |

| Type of Treatment: | |

| Chemotherapy | 49 |

| Radiation | 10 |

| Combined Chemo & Radiation | 25 |

| Other | 16 |

| Relationship of Caregiver: | |

| Spouse | 46 |

| Parent | 33 |

| Child | 9 |

| Other | 12 |

missing data n=10

missing data n=l

missing data n=7

Table 3.

Demographic Characteristics of Caregivers

| Characteristic | N (with sample size, N approximates % unless otherwise noted) |

|---|---|

| Age (range = 18–76) | Mean = 53.513, SD = 13.43 |

| Duration of Caregiving1 (range = 1 – 348 months) | Median = 8.5 |

| 1–12 months | 62 (67%) |

| 13–36 months | 17 (18%) |

| 37 months or more | 13 (14%) |

| Hours per Week Spent Caregiving (0 – 168) | Mean = 54.6 hrs., SD = 62.4 |

| Sex: | |

| Female | 69 |

| Male | 31 |

| Race2: | |

| White | 86 |

| Other | 13 |

| Education3: | |

| Some College | 79 (81%) |

| No College | 19 (19%) |

| Employment: | |

| Full or Part-Time Work | 33 |

| Retired | 16 |

| Disabled, Unemployed | 26 |

| Other | 25 |

| Insurance2: | |

| Yes | 87 |

| No | 12 |

| Patient’s Type of Cancer: | |

| Hematologic | 32 |

| Colorectal | 14 |

| Upper GI | 13 |

| Other | 41 |

| Type of Treatment: | |

| Chemotherapy | 49 |

| Radiation | 10 |

| Combined Chemo & Radiation | 25 |

| Other | 16 |

| Relationship to Patient: | |

| Spouse | 64 |

| Child | 15 |

| Parent | 7 |

| Other | 14 |

missing data n=8

missing data n=l

missing data n=2

While 58% of patients identified “dealing with feelings” as an activity they do on their own, 33% of patients reported needing help with this and 7% indicated they needed more information about “dealing with feelings.” When asked to identify the most difficult tasks for them to do independently, patients indicated physical activities (7%), specifically household activities and meal preparation (11%). Very few patients (3%) identified emotional tasks as most difficult for them. On the other hand, 19% perceived the psychosocial aspects of caregiving as the most difficult for their caregivers. Three patients (3%) commented that “putting up with me” is the most difficult part of caregiving for their loved ones.

Family caregivers frequently reported helping cancer patients manage the psychological impact of their cancer, with most caregivers (81%) reporting they help their loved one deal with their feelings about cancer. A small portion of caregivers (13%) found this difficult to do and a quarter (25%) indicated they wanted more information about how to help their loved one deal with their feelings about cancer. About a third of the caregivers (36%) reported the hardest part of caregiving was the psychosocial aspect, with most of these (20%) stating that providing emotional support for their loved one was the most difficult. Caregivers described what they found to be difficult in providing emotional support: “talk[ing] with her and helping her deal with it, especially when bad news is given,” and “know[ing] what to say to console her when she is low in spirits.” Other caregivers reported the greatest difficulty to be managing their own coping (8%). These challenges were described as “keeping my feeling of worry to myself,” and “offer[ing] support when I am having a hard time also.” A number of caregivers (13%) reported their perception that dealing with the emotional aspects of cancer was the hardest part for their loved one with cancer. Specific comments in this area tended to focus on coping with cancer, e.g. “deal[ing] with feelings about cancer,” or on accepting limitations, e.g. “to accept that his routine/eating habits, etc are altered....”

A small number of caregivers (8%) described “watch[ing] their suffering” as the most difficult aspect of caregiving for them, with several noting the challenges of watching a loved one decline. Patients were also aware that this was a challenge for their loved ones, and 5% of patients reported their belief that watching their suffering was the most difficult aspect for their caregivers. One patient described the greatest difficulty for his caregiver to be “watching the troubles I go through.”

When asked specifically about their educational needs, 19% of patients indicated they would like more information about how to deal with their feelings. In comparison, 31% of caregivers responded they would like more information to help with their emotional coping. Many added comments to expand on their responses to the question. Some spoke of difficulty adjusting to the caregiving role, such as: “It seems it all falls on your shoulders as the caregiver - other family members aren’t always there for support. It seems like cancer can break apart a family too.” While others focused on the emotional impact of dealing with cancer in the context of the family, such as this concern: “Would like more information as to how to cope as a family and as a caregiver.” Another expressed concern for “not showing my worry around him or kids, [I] need ways to help me cope.”

In describing the non-medical problems that challenge them, some patients’ responses (16%) indicated these areas of concern: dealing with emotional issues, managing the household, caring for others, and dealing with financial concerns. One patient noted her nonmedical concerns to be “stress, anxiety, depression, childcare, would like to be able to pay the person taking care of my children, would like help paying my hospital bills.”

A particular area in which caregivers help cancer patients is in handling the logistical aspects of receiving cancer care, with most (69%) reporting that they help their loved one with insurance problems (in comparison, 54% of patients indicated they needed help managing their insurance and medical bills). While 5% of caregivers listed emotional support as the most difficult nonmedical aspect of caregiving for them, 6% identified logistical or financial tasks as the most difficult nonmedical task.

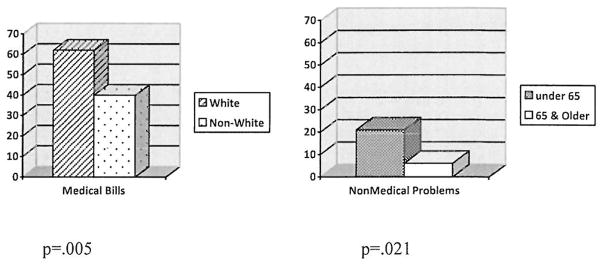

We examined the association of demographic variables with patients’ and caregivers’ stated needs. For patients, the association of race and medical bills/insurance was significant, with white patients being more likely to state that they needed help managing their medical bills and health insurance compared with minority patients (63% versus 40%, p = .005) (see Figure 1). Also, among all patients, those furthest from their diagnosis reported needing more help dealing with insurance and medical bills (F = 4.59, p = .035). In addition, the association between age and dealing with feelings approached significance, suggesting that younger patients (under age 65) may be more likely than older patients to need help dealing with feelings (41% versus 18%, p = .053). Finally, age was associated with needing help with nonmedical problems, with younger patients reporting greater need for this type of help than older patients (21% vs. 6%, p = .021) (see Figure 1). This need was reflected in specific comments from 8% of patients about needing help with childcare.

Figure 1.

Percentage of Patients Reporting Needing Help

There was only one significant association between demographics and psychosocial needs for caregivers. The overall number of hours spent providing care was positively associated with the likelihood of helping with managing feelings (F = 4.25, p=0.04). Another association approached significance, specifically difficulty providing assistance with nonmedical problems and the overall number of hours spent helping. Those caregivers reporting greater difficulty helping with nonmedical problems tended to be those spending more time at caregiving (X = 106 hours versus X = 52 hours, F = 3.72, p = .057).

Discussion

Half of the patient participants reported their spouse to be their primary caregiver, while more than half of the caregivers defined their relationship as spouse to their loved one with cancer. Others have indicated that adult children are the most common caregivers, followed by spouses [2, 4]; therefore our sample may be slightly different from the norm. Our family caregivers spent an average of 7.8 hours per day at caregiving, only slightly lower than the 8.3 hours reported previously [5], but higher than the 20 hours per week reported by the National Alliance for Caregiving [4]. The U.S. Census Bureau reported that 46.3 million people were without health insurance in 2008, representing 15.4% of the population [24]. Among our patients, 83% reported having insurance, which is slightly less than the national average. Despite the majority of our sample having health insurance, slightly more than half of the patients reported needing help dealing with insurance and medical bills and most of the caregivers indicated that they provide assistance with managing insurance and medical bills.

Several discrepancies were identified in patients’ and caregivers’ perceptions of caregiving. First, a slight majority of patients indicated they manage their emotions on their own, but almost half reported they needed help managing their emotions. In comparison, more than 80% of caregivers reported they help their loved one with cancer deal with their emotions. This result suggests cancer caregivers may be particularly vulnerable given previous research [25] which has indicated that providing emotional support is more burdensome than providing personal care. Second, while only about 20% of patients thought the psychosocial aspects of caregiving were the most difficult for their caregivers, about a third of caregivers considered this aspect to be the most difficult. This result suggests patients may underestimate how difficult this component of caregiving can be. Third, in describing their educational needs, about 20% of patients reported they would like more information about how to deal with feelings, while almost a third of caregivers indicated they would like this type of information.

Surprisingly, the demographic and clinical variables were minimally associated with patients’ and caregivers’ psychosocial needs related to caregiving. The most noteworthy associations concerned needing help with management of patients’ medical bills and health insurance. More white patients (versus non-white) indicated they needed help managing their medical bills and health insurance. Also, patients who had been dealing with their cancer longer reported needing more help managing their medical bills and insurance than newly diagnosed patients, perhaps reflecting the accumulation of medical bills over time. This result may also suggest that patients get “worn down” when their illness fails to resolve, requiring more assistance.

The examination of the three specific psychosocial tasks of caregiving in cancer patients highlighted in this study indicates that, although these tasks are frequently performed by both patients and their caregivers, both groups have reported needing more information and assistance in performing these tasks. Taking these needs into account, an important next step would be to develop an intervention to address these learning needs. Options to consider include psycho-educational programs, skill building classes, and therapeutic counseling, all of which are interventions that have demonstrated small to medium effect in reducing caregiver burden, improving ability to cope, increasing sense of self-efficacy, and improving quality of life (26). Another possibility includes problem-solving interventions, which not only deliver information but are also tied to skill building, and which can help caregivers to feel more prepared and less stressed (27).

The results of this study are limited by our use of unrelated patients and caregivers, rather than using dyads. This leaves the possibility that discrepancies between patients’ and caregivers’ perceptions may be due in part to different illness situations, rather than solely due to differences in role (patient or caregiver). For example, no caregiver reported that their loved one had breast cancer or lung cancer, although these cancers were represented in the patient group. It would be helpful to examine whether the differences observed in caregivers’ and patients’ psychosocial needs in this study are representative of patient and caregiver dyads.

Another limitation is the homogeneity of our samples. Both are predominantly white and fairly well-educated. While over 80% of both our patient and caregiver samples reported having health insurance, this is comparable with U.S. Census Bureau reports of the percentage of uninsured Americans [24]. A final limitation is our use of a convenience sample, which relied on passive recruitment of participants. While this form of recruitment was utilized because of the exploratory nature of this study, it may have limited the generalizability of our results due to the use of a nonrandom sample.

The results of this study suggest that patients and family caregivers are acutely aware of the psychosocial aspects of caregiving, with a noteworthy minority of patients endorsing their need for assistance in managing the emotional aspects of their cancer and a strong majority of caregivers reporting they provide this type of assistance. There were some discrepancies in how psychosocial aspects of caregiving were perceived by patients and by caregivers. These results suggest that attention to psychosocial needs is an important topic to be addressed in educational programs designed for caregivers about providing care to cancer patients. Future research is needed to determine the best way to address the psychosocial needs of cancer patients and family caregivers in the context of informal caregiving.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the support of the Biostatistics Core, Siteman Comprehensive Cancer Center and NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA091842.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors note that this research was funded by the Siteman Cancer Center and Barnes-Jewish Hospital, the employer for Dr. Deshields, Dr. Potter, Dr. M. Kuhrik, Dr. N. Kuhrik, and Ms. O’Neill. Otherwise, there is no financial relationship that compromises the integrity of the data reported here. The authors have full control of the data and agree to make the data available to the journal to review, if needed.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegal R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun M. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robison J, Fortinsky R, Kleppinger A, Shugrue N, Porter M. A broader view of family caregiving: Effects of caregiving and caregiver conditions on depressive symptoms, health, work and social isolation. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64:788–798. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Department of Health and Human Services. Informal caregiving: Compassion in action. Washington, DC: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Alliance for Caregiving. [Accessed August 2010];Caregiving in the United States: Executive summary, National Alliance for Caregiving in association with the American Association of Retired Persons November 2009. 2010 http://www.caregiving.org/data.

- 5.Yabroff KR, Kim Y. Time costs associated with informal caregiving for cancer survivors. Cancer. 2009;115:4362–4373. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Ryn M, Sanders S, Kahn K, van Houtven C, Griffin J, et al. Objective burden, resources, and other stressors among informal cancer caregivers: a hidden quality issue? Psycho-Oncol. 2010 doi: 10.1002/pon.1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Given B, Given C, Kozachik S. Family support in advanced cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2001;51:213–231. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.51.4.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bakas T, Lewis RR, Parsons JE. Caregiving tasks among family caregivers of patients with lung cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2001;28:847–854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sherwood P, Donovan H, Given C, Lu X, et al. Predictors of employment and lost hours from work in cancer caregivers. Psycho-Oncol. 2008;17:598–605. doi: 10.1002/pon.1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Himmelstein DU, Thorne D, Warren E, Woolhandler S. Medical bankruptcy in the United States, 2007: Results of a national study. Am J Med. 2009;122:741–746. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yun Y, Rhee Y, Kang I, Lee J, Bang S, et al. Economic burdens and quality of life of family caregivers of cancer patients. Oncology. 2005;68:107–114. doi: 10.1159/000085703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schubart J, Kinzie M, Farace E. Caring for the brain tumor patient: Family caregiver burden and unmet needs. Neuro Oncol. 2008;10:61–72. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2007-040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yabroff KR, Lawrence W, Clauser S, Davis W, Brown M. Burden of illness in cancer survivors: Findings from a population-based national sample. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1322–1330. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braun M, Mikulincer M, Rydall A, Walsh A, Rodin G. Hidden morbidity in cancer: Spouse caregivers. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4829–4834. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schumacher K, Stewart B, Archbold P, Capparro M, et al. Effects of caregiving demand, mutuality, and preparedness on family caregiver outcomes during cancer treatment. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35:49–56. doi: 10.1188/08.ONF.49-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spillers RL, Wellisch DK, Kim Y, Matthews BA, Baker F. Family caregivers and guilt in the context of cancer care. Psychosomatics. 2008;49:511–519. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.49.6.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaugler J, Linder J, Given C, Kataria R, et al. The proliferation of primary cancer caregiving stress to secondary stress. Cancer Nurs. 2008;31:116–123. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000305700.05250.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schumacher K, Stewart B, Archbold P. Mutuality and preparedness moderate the effects of caregiving demand on cancer family caregiver outcomes. Nurs Res. 2007;56:425–433. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000299852.75300.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bloom J. Surviving and thriving? Psycho-Oncol. 2002;11:89–92. doi: 10.1002/pon.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beckjord E, Arora N, McLaughlin W, Oakley-Girvan I, et al. Health-related information needs in a large and diverse sample of adult cancer survivors: Implications for cancer care. J Cancer Surviv. 2008;2:179–189. doi: 10.1007/s11764-008-0055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ross S, Mosher C, Ronis-Robin V, Hermele S, Ostroff J. Psychosocial adjustment of family caregivers of head and neck cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:171–178. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0641-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Potter P, Deshields T, Kuhrik M, Kuhrik N, et al. An analysis of educational and learning needs of cancer patients and unrelated family caregivers. J Cancer Educ. 2010 doi: 10.1007/sl3187-010-0076-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 24.U.S. Census Bureau. [Accessed June 2010];Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2008. 2009 http://www.census.gov/prod/2009pubs/p60-236.pdf.

- 25.Oberst MT, Thomas SE, Gass KA, Ward SE. Caregiving demands and appraisal of stress among family caregivers. Cancer Nurs. 1989;12:209–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Northouse L, Katapodi M, Song L, Zhang L, Mood D. Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:317–339. doi: 10.3322/caac.20081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bucher J, Loscalzo M, Zabora J, Houts P, et al. Problem-solving cancer care education for patients and caregivers. Cancer Practice. 2001;9:66–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2001.009002066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]