Abstract

Recent HIV research suggested assessing adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) as contributing factors of HIV risk behaviors. However, studies often focused on a single type of adverse experience and very few utilized population-based data. This population study examined the associations between ACE (individual and cumulative ACE score) and HIV risk behaviors. We analyzed the 2012 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey (BRFSS) from 5 states. The sample consisted of 39,434 adults. Eight types of ACEs that included different types of child abuse and household dysfunctions before the age of 18 were measured. A cumulative score of ACEs was also computed. Logistic regression estimated of the association between ACEs and HIV risk behaviors using odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for males and females separately. We found that ACEs were positively associated with HIV risk behaviors overall, but the associations differed between males and females in a few instances. While the cumulative ACE score was associated with HIV risk behaviors in a stepwise manner, the pattern varied by gender. For males, the odds of HIV risk increased at a significant level as long as they experienced one ACE, whereas for females, the odds did not increase until they experienced three or more ACEs. Future research should further investigate the gender-specific associations between ACEs and HIV risk behaviors. As childhood adversities are prevalent among general population, and such experiences are associated with increased risk behaviors for HIV transmission, service providers can benefit from the principles of trauma-informed practice.

Abbreviations: ACE, adverse childhood experience; BRFSS, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey; OR, Odds ratio; CI, confidence intervals

Keywords: Adverse childhood experience, Childhood trauma, HIV risk behaviors, Gender-specific, Sexual health

Highlights

-

•

Two in three U.S. adults experienced one or more adversities in childhood.

-

•

Strong associations between ACEs and HIV risk behaviors are found.

-

•

The associations between ACEs and HIV risk behaviors vary by gender.

-

•

Males with childhood adversities are more vulnerable to risk behaviors than females.

-

•

Prevention programs should examine childhood adversities and be gender-specific.

1. Introduction

We have entered the fourth decade of HIV/AIDS pandemic. In the United States, an approximate of 1.2 million people is living with HIV/AIDS, while 50,000 individuals are getting infected each year (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014). Risk behaviors for HIV infection and transmission include the sharing of needles and syringes, the conduct of unprotected anal intercourse, the exchange of sex for drug or money, and the contraction of other sexual transmitted diseases (McGowan et al., 2004, Patrick et al., 2012). These behaviors are associated with a range of psychosocial problems such as depression and suicidal ideation (Pettes et al., 2015, Hallfors et al., 2004, Brown et al., 2006), psychological distress (Brown et al., 2006, DiClemente et al., 2001, Elkington et al., 2010), alcohol and marijuana use (Patrick et al., 2012, Elkington et al., 2010), disrupted social support (St. Lawrence et al., 1994, Diaz et al., 2004, DiClemente et al., 2008), and interpersonal violent experience (Salas-Wright et al., 2015, Kouyoumdjian et al., 2013).

Despite the rich literature concerning HIV risk behaviors, new perspectives continue to emerge in recent years. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), including abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction (Anda et al., 2008), have acquired attention in HIV research. Large-scale cohort studies from countries such as Finland, the United States, and the Philippines demonstrate that the majority of general public (52%–74%) have experienced at least one form of ACEs before they reached 18 years old (Anda et al., 2006, Felitti et al., 1998, Haatainen et al., 2003, Hillis et al., 2000, Ramiro et al., 2010, Schussler-Fiorenza Rose et al., 2014). ACEs have been linked to alteration of the neurobiological stress–response systems (Anda et al., 2006), resulting in negative physical health outcome, such as cancers (Brown et al., 2010, van der Meer et al., 2012), asthma (Remigio-Baker et al., 2015), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Anda et al., 2008), and premature mortality (Brown et al., 2009). Childhood adversities are also linked with poor mental health and substance use outcomes (Schilling et al., 2007).

1.1. ACEs and gender

Studies have shown that females are more likely to experience childhood sexual abuse (Cavanaugh et al., 2015, Afifi et al., 2008) and witness domestic violence (Afifi et al., 2008), while males are more likely to report childhood physical abuse (Haatainen et al., 2003, Afifi et al., 2008) and familial substance abuse (Messina et al., 2008). Whether the manifestation of ACE differs by gender remains inconclusive. Some studies suggest that there is no gender difference between childhood sexual abuse and long-term physical health (Dube et al., 2005) and mental health outcomes (Schilling et al., 2007, Mersky et al., 2013). However, others indicate that compared to their male counterparts, females who experienced ACEs are more likely to feel hopelessness (Haatainen et al., 2003), smoke cigarettes (Fuller-Thomson et al., 2013), and have depression and anxiety disorder in adulthood (Cavanaugh et al., 2015, Afifi et al., 2008), while males are more likely to report alcohol abuse or misuse (Dube et al., 2002) and antisocial behavior in young adulthood (Schilling et al., 2007).

1.2. ACEs, gender difference, and HIV risk behaviors

Empirical studies have investigated the relationship between ACEs, gender, and HIV risk behaviors. However, they often focus on a single type of adverse experience (e.g., childhood sexual abuse), or a specific population (e.g. men who have sex with men). For example, a systematic literature review of childhood sexual abuse and subsequent sexual risk behavior has documented that childhood sexual abuse is linked with increased HIV risk behaviors among both females and males (Senn et al., 2008). Studies using convenience samples also suggest that childhood sexual abuse was associated with multiple sexual partners and unprotected sex among heterosexual males, compared to homosexual males and heterosexual females (Whetten et al., 2012). Among gay and bisexual men, those who had a history of childhood sexual abuse are at an increased risk to have multiple sexual partners and use recreational drugs before sex (Brennan et al., 2007). A large-scale study suggests that females who had experienced more ACEs were likely to report greater sexual risk behaviors (Hillis et al., 2001). In a separate study, the same group of authors also found that sexually transmitted diseases increased as the number of ACE exposure elevated for both males and females (Hillis et al., 2000). Notably, the two studies were based on a landmark study whose data were collected in 1995–1996 and consisted of responses from managed care company members who predominately collected from a middle- or upper-middle-class background (Cronholm et al., 2015).

The purpose of this study is to build on previous literature on ACE and HIV risk behaviors. There is a need for more HIV prevention research that examines a more comprehensive measure of ACE, understands the role of gender, and employs current, population-based data. Using the 2012 Brief Risk Factor Surveillance Survey (BRFSS) data, the present study conducts gender-specific analyses to understand the relationship between a range of childhood adversities and HIV risk behaviors. We also examined the cumulative impact of multiple ACEs because different forms of ACEs are likely to co-occur (Dube et al., 2009). The study tested two hypotheses: 1) each individual form of ACE is positively associated with HIV risk behaviors; and 2) the number of ACEs is positively linked to HIV risks.

2. Methods

2.1. Data and study sample

The 2012 BRFSS dataset is a nationally representative, cross-sectional telephone (both landline and cellular) survey developed in collaborations between the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and each state's public health departments. Using standardized questionnaires, BRFSS asks adults who are 18 years of age and older living in households questions concerning their risk behaviors about chronic health conditions as well as their preventive health practices (Centers for Disease and Prevention, 2013a). To ensure that the BRFSS is a uniform and yet state-specific survey, each year the questionnaire consists of core questions that all states must use and optional modules that each state can select. Five states – Iowa, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Wisconsin – included ACE modules in their 2012 BRFSS (Centers for Disease and Prevention, 2013a). Detailed information about the study design and methodology is available from the CDC's website: http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/. As BRFSS datasets are publicly accessible and the data do not contain personally identifiable information, the study is exempted from the university's ethics review.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Adverse childhood experiences

We assessed eight ACEs that happened before the participants were 18 years old. They included: 1) living with someone who had mental health issues (“Did you live with anyone who was depressed, mentally ill, or suicidal?”); 2) living with someone who abused alcohol or drugs (“Did you live with anyone who was a problem drinker or alcoholic?”); 3) living with someone who was incarcerated (“Did you live with anyone who served time or was sentenced to serve time in a prison, jail, or other correctional experiences?”); 4) parents separated or divorced (“Were your parents separated or divorced?”); 5) witnessing physical violence at home (“How often did your parents or adults in your home ever slap, hit, kick, punch, or beat each other up?”); 6) experiencing physical abuse “How often did a parent or adult in your home ever hit, beat, kick, or physically hurt you in any way? Do not include spanking.”); 7) experiencing verbal abuse (“How often did a parent or adult in your home ever swear at you, insult you, or put you down?”); 8) sexual abuse (if participant answers “once” or “more than once” to one of the following three items: “How often did anyone at least 5 years older than you or an adult ever touch you sexually?”, “How often did anyone at least 5 years older than you or an adult try to make you touch them sexually?”, and “How often did anyone at least 5 years older than you or an adult force you to have sex?”). All responses were dichotomized into “yes” or “no”.

2.2.2. Depression

Participants were asked one question, “Has a doctor, nurse, or other health professional ever told you that you have a depressive disorder, including depression, major depression, dysthymia, or minor depression?” (0 = “No″, 1 = “Yes”).

2.2.3. Alcohol and tobacco use

Participants reported their drinking behavior on this question, “During the past 30 days, how many days per week or per month did you have at least one drink of any alcoholic beverage such as beer, wine, a malt beverage or liquor?”. Their responses were coded as: 0 = “Abstinence” (0 drink per day), 1 = “Moderate” (1 drink per day for females; 1 or 2 drinks per day for males), and 2 = “Heavy” (2 or more drinks per day for females; 3 or more drinks per day for males). They also self-reported their smoking on one question, “Do you now smoke cigarettes every day, some days, or not at all?” Their smoking status was categorized into 0 = “Not current smoker” and 1 = “Current smoker”.

2.2.4. HIV risk behaviors

Participants endorsed on a single question if any of the following four situations happened to them in the past year: “You have used intravenous drugs”, “You have been treated for a sexually transmitted or venereal disease”, “You have given or received money or drugs in exchange for sex”, and “You had anal sex without a condom” (0 = “No”, 1 = “Yes”).

2.2.5. Demographic variables

Participants reported their age (0 = “18–24 years”, 1 = “25–34 years”, 2 = “35–44 years”; 3 = “45–54 years”, 4 = “55–64 years”, 5 = “65–99 years”), sex (0 = “Male”, 1 = “Female”), race (0 = “Non-Hispanic White”, 1 = “White”), marital status (0 = “Not married”, 1 = “Married or common law”), educational attainment (0 = “Not high school”, 1 = “High school or GED”, “Some college”, or “College graduate and above”), and annual income (0 = “<$15,000”, 1 = “15,000–24,999”, 2 = “$25,000–$49,999”, 3 = “$50,000–$74,999”, 4 = “≥$75,000”).

2.3. Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 23 (IBM SPSS Inc., 2015). Data were weighted based on the population weights and sampling units provided by Centers for Disease and Prevention (Centers for Disease and Prevention, 2013b). We conducted two sets of hierarchical logistic regression analysis to answer study questions, the first set examining the association between each of eight ACEs and HIV risk behaviors (hypothesis 1), and the second assessing the association between accumulative ACE scores and HIV risk behaviors (hypothesis 2). In each set of analyses, we controlled for demographic variables, substance use (alcohol and tobacco use), and depression. Given that multiple comparisons are conducted, Bonferroni correction (Bland and Altman, 1995) was used to correct for multiple testing, where the critical p value was set at 0.05/9 = 0.0056 for the study.

3. Results

Study sample consists of a total of 39,434 individuals (19,110 males and 20,324 females). Information about participants' background characteristics, adverse childhood experiences, and HIV risk behaviors are reported in Table 1. Except for race, males and females are different in all background variables. Statistically significant differences were found between females and males in that females are older, and more females are married, have completed some college, have lower income, and have had a depressive disorder. More females than males had in their childhood lived with someone depressed, mentally ill, or suicidal, lived with a substance abuser, witnessed interpersonal violence, experienced sexual abuse, and experienced four or more ACEs. Compared to females, more males drink moderately or heavily, and currently smoke cigarettes, and have engaged in HIV risk behaviors in the past year.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics, ACEs, and adult HIV risk behaviors by gender of the 2012 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey (BRFSS) data from Iowa, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Wisconsin.

| Male |

Female |

p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Demographics | |||||

| Age (years) | < 0.0001 | ||||

| 18–24 | 2615 | 13.7 | 2480 | 12.3 | |

| 25–34 | 3295 | 17.3 | 3263 | 16.2 | |

| 35–44 | 3244 | 17.0 | 3265 | 16.2 | |

| 45–54 | 3546 | 18.6 | 3662 | 18.2 | |

| 55–64 | 3115 | 16.4 | 3267 | 16.2 | |

| 65–99 | 3219 | 16.9 | 4229 | 21.0 | |

| Race | 0.43 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 14,390 | 75.9 | 15,412 | 76.2 | |

| Hispanic or non-White | 4570 | 24.1 | 4803 | 23.8 | |

| Marital status | < 0.0001 | ||||

| Not married | 8025 | 42.1 | 9200 | 45.4 | |

| Married or common law | 11,024 | 57.9 | 11,067 | 54.6 | |

| Education | < 0.0001 | ||||

| Less than high school | 2896 | 15.2 | 2739 | 13.5 | |

| High school or GED diploma | 6219 | 32.7 | 6133 | 30.2 | |

| Some college | 5644 | 29.6 | 6719 | 33.1 | |

| College or graduate degree | 4286 | 22.5 | 4695 | 23.1 | |

| Income (US$) | < 0.0001 | ||||

| < 15,000 | 1837 | 11.1 | 2336 | 14.1 | |

| 15,000–24,999 | 3107 | 18.8 | 3548 | 21.4 | |

| 25,000–49,999 | 4685 | 28.3 | 4550 | 27.4 | |

| 50,000–74,999 | 2606 | 15.8 | 2529 | 15.2 | |

| ≥ 75,000 | 4299 | 26.0 | 3642 | 21.9 | |

| Mental health and substance use status | |||||

| Depressive disorder | < 0.0001 | ||||

| No | 16,320 | 85.7 | 15,760 | 77.8 | |

| Yes | 2721 | 14.3 | 4491 | 22.2 | |

| Alcohol use | < 0.0001 | ||||

| Abstainer | 8131 | 44.3 | 11,415 | 57.9 | |

| Moderate | 7247 | 39.5 | 5667 | 28.8 | |

| Heavy | 2988 | 16.3 | 2626 | 13.3 | |

| Cigarette use | < 0.0001 | ||||

| No | 14,320 | 76.7 | 15,910 | 79.8 | |

| Yes | 4351 | 23.3 | 4021 | 20.2 | |

| Types of ACE | |||||

| Lived with someone depressed, mentally ill, or suicidal | < 0.0001 | ||||

| No | 13,279 | 86.5 | 13,623 | 80.9 | |

| Yes | 2071 | 13.5 | 3220 | 19.1 | |

| Lived with substance abuser | < 0.0001 | ||||

| No | 11,462 | 74.2 | 12,061 | 71.3 | |

| Yes | 3988 | 25.8 | 4854 | 28.7 | |

| Family member incarceration | 0.028 | ||||

| No | 14,067 | 91.2 | 15,503 | 91.9 | |

| Yes | 1357 | 8.8 | 1369 | 8.1 | |

| Parents divorced | 0.465 | ||||

| No | 11,019 | 72.7 | 11,947 | 72.3 | |

| Yes | 4148 | 27.3 | 4581 | 27.7 | |

| Interpersonal violence | < 0.0001 | ||||

| No | 12,804 | 84.4 | 13,632 | 82.0 | |

| Yes | 2365 | 15.6 | 2991 | 18.0 | |

| Physical abuse | 0.732 | ||||

| No | 12,953 | 84.8 | 14,201 | 84.7 | |

| Yes | 2320 | 15.2 | 2571 | 15.3 | |

| Verbal abuse | 0.421 | ||||

| No | 10,346 | 68.1 | 11,291 | 67.7 | |

| Yes | 4845 | 31.9 | 5392 | 32.3 | |

| Sexual abuse | < 0.0001 | ||||

| No | 14,286 | 93.4 | 14,176 | 84.8 | |

| Yes | 1011 | 6.6 | 2550 | 15.2 | |

| Number of ACEs | < 0.0001 | ||||

| 0 | 5893 | 40.7 | 6274 | 39.6 | |

| 1 | 3616 | 24.9 | 3558 | 22.4 | |

| 2 | 1895 | 13.1 | 1905 | 12.0 | |

| 3 | 1213 | 8.4 | 1449 | 9.1 | |

| 4 + | 1878 | 13.0 | 2670 | 16.8 | |

| HIV risk behaviors | < 0.0001 | ||||

| No | 17,166 | 95.8 | 18,643 | 96.8 | |

| Yes | 750 | 4.2 | 610 | 3.2 | |

Table 2 shows the bivariate relationships between study variables and HIV risk behaviors by gender. For both males and females, HIV risk behaviors tend to occur among those who are younger, are non-white, are not married, have less income, have a depressive disorder, drink alcohol, and smoke cigarettes.

Table 2.

Bivariate relationships between study variables and adult HIV risk behaviors. The 2012 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey (BRFSS) from Iowa, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Wisconsin.

| Male |

Female |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV risk behavior presence |

HIV risk behavior presence |

|||||||||

| No |

Yes |

p | No |

Yes |

p | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Demographics | ||||||||||

| Age (years) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||

| 18–24 | 2185 | 12.8 | 253 | 33.8 | 2118 | 11.4 | 208 | 34.2 | ||

| 25–34 | 2817 | 16.5 | 255 | 34.1 | 2908 | 15.7 | 197 | 32.3 | ||

| 35–44 | 2989 | 17.5 | 90 | 12.0 | 3019 | 16.3 | 110 | 18.1 | ||

| 45–54 | 3265 | 19.1 | 69 | 9.2 | 3429 | 18.5 | 56 | 9.2 | ||

| 55–64 | 2884 | 16.8 | 51 | 6.8 | 3093 | 16.7 | 27 | 4.4 | ||

| 65–99 | 2977 | 17.4 | 30 | 4.0 | 3948 | 21.3 | 11 | 1.8 | ||

| Race | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 13,118 | 76.9 | 459 | 61.9 | 14,315 | 77.1 | 361 | 59.7 | ||

| Hispanic or non-White | 3933 | 23.1 | 283 | 38.1 | 4240 | 22.9 | 244 | 40.3 | ||

| Marital status | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||

| Not married | 6924 | 40.4 | 538 | 71.9 | 8189 | 44.0 | 420 | 69.2 | ||

| Married or common law | 10,204 | 59.6 | 210 | 28.1 | 10,415 | 56.0 | 187 | 30.8 | ||

| Education | < 0.0001 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Less than high school | 2491 | 14.5 | 167 | 22.3 | 2431 | 13.1 | 103 | 16.9 | ||

| High school or GED diploma | 5522 | 32.2 | 247 | 32.9 | 5577 | 30.0 | 178 | 29.2 | ||

| Some college | 5135 | 30.0 | 225 | 30.0 | 6190 | 33.2 | 219 | 36.0 | ||

| College or graduate degree | 3982 | 23.2 | 111 | 14.8 | 4421 | 23.7 | 109 | 17.9 | ||

| Income (US$) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||

| < 15,000 | 1592 | 10.6 | 101 | 16.1 | 2060 | 13.4 | 110 | 22.5 | ||

| 15,000–24,999 | 2742 | 18.2 | 164 | 26.1 | 3228 | 21.0 | 135 | 27.6 | ||

| 25,000–49,999 | 4243 | 28.2 | 211 | 33.6 | 4263 | 27.7 | 126 | 25.8 | ||

| 50,000–74,999 | 2440 | 16.2 | 68 | 10.8 | 2397 | 15.6 | 56 | 11.5 | ||

| ≥ 75,000 | 4044 | 26.9 | 84 | 13.4 | 3452 | 22.4 | 62 | 12.7 | ||

| Mental health and substance use status | ||||||||||

| Depressive disorder | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||

| No | 14,755 | 86.3 | 578 | 77.2 | 14,532 | 78.2 | 363 | 59.7 | ||

| Yes | 2350 | 13.7 | 171 | 22.8 | 4049 | 21.8 | 245 | 40.3 | ||

| Alcohol use | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||

| Abstainer | 7587 | 44.9 | 235 | 32.0 | 10,788 | 58.5 | 234 | 38.9 | ||

| Moderate | 6579 | 38.9 | 379 | 51.6 | 5219 | 28.3 | 245 | 40.7 | ||

| Heavy | 2745 | 16.2 | 120 | 16.3 | 2421 | 13.1 | 123 | 20.4 | ||

| Cigarette use | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||

| No | 13,320 | 77.9 | 399 | 53.5 | 14,987 | 80.7 | 381 | 62.5 | ||

| Yes | 3772 | 22.1 | 347 | 46.5 | 3592 | 19.3 | 229 | 37.5 | ||

| Types of ACE | ||||||||||

| Lived with someone depressed, mentally ill, or suicidal | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||

| No | 12,729 | 87.0 | 475 | 73.9 | 13,242 | 81.6 | 304 | 59.5 | ||

| Yes | 1900 | 13.0 | 168 | 26.1 | 2995 | 18.4 | 207 | 40.5 | ||

| Lived with substance abuser | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||

| No | 11,069 | 75.2 | 334 | 51.2 | 11,774 | 72.2 | 218 | 42.0 | ||

| Yes | 3651 | 24.8 | 318 | 48.8 | 4525 | 27.8 | 301 | 58.0 | ||

| Family member incarceration | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||

| No | 13,479 | 91.7 | 519 | 79.7 | 15,043 | 92.5 | 365 | 71.2 | ||

| Yes | 1216 | 8.3 | 132 | 20.3 | 1218 | 7.5 | 148 | 28.8 | ||

| Parents divorced | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||

| No | 10,635 | 73.5 | 333 | 53.3 | 11,626 | 73.0 | 261 | 52.3 | ||

| Yes | 3831 | 26.5 | 292 | 46.7 | 4307 | 27.0 | 238 | 47.7 | ||

| Interpersonal violence | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||

| No | 12,287 | 85.0 | 456 | 71.1 | 13,219 | 82.5 | 342 | 67.5 | ||

| Yes | 2167 | 15.0 | 185 | 28.9 | 2809 | 17.5 | 165 | 32.5 | ||

| Physical abuse | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||

| No | 12,426 | 85.4 | 464 | 72.2 | 13,788 | 85.3 | 334 | 65.0 | ||

| Yes | 2132 | 14.6 | 179 | 27.7 | 2376 | 14.7 | 180 | 35.0 | ||

| Verbal abuse | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||

| No | 9978 | 68.9 | 310 | 48.4 | 11,044 | 68.7 | 193 | 37.5 | ||

| Yes | 4496 | 31.1 | 330 | 51.6 | 5038 | 31.3 | 321 | 62.5 | ||

| Sexual abuse | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||

| No | 13,680 | 93.8 | 537 | 83.3 | 13,799 | 85.6 | 297 | 58.0 | ||

| Yes | 900 | 6.2 | 108 | 16.7 | 2325 | 14.4 | 215 | 42.0 | ||

| Number of ACEs | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||

| 0 | 5777 | 41.8 | 88 | 14.6 | 6178 | 40.3 | 67 | 14.2 | ||

| 1 | 3480 | 25.2 | 124 | 20.6 | 3494 | 22.8 | 54 | 11.5 | ||

| 2 | 1784 | 12.9 | 100 | 16.6 | 1833 | 12.0 | 63 | 13.4 | ||

| 3 | 1104 | 8.0 | 104 | 17.2 | 1372 | 9.0 | 66 | 14.0 | ||

| 4 + | 1686 | 12.2 | 187 | 31.0 | 2437 | 15.9 | 221 | 46.9 | ||

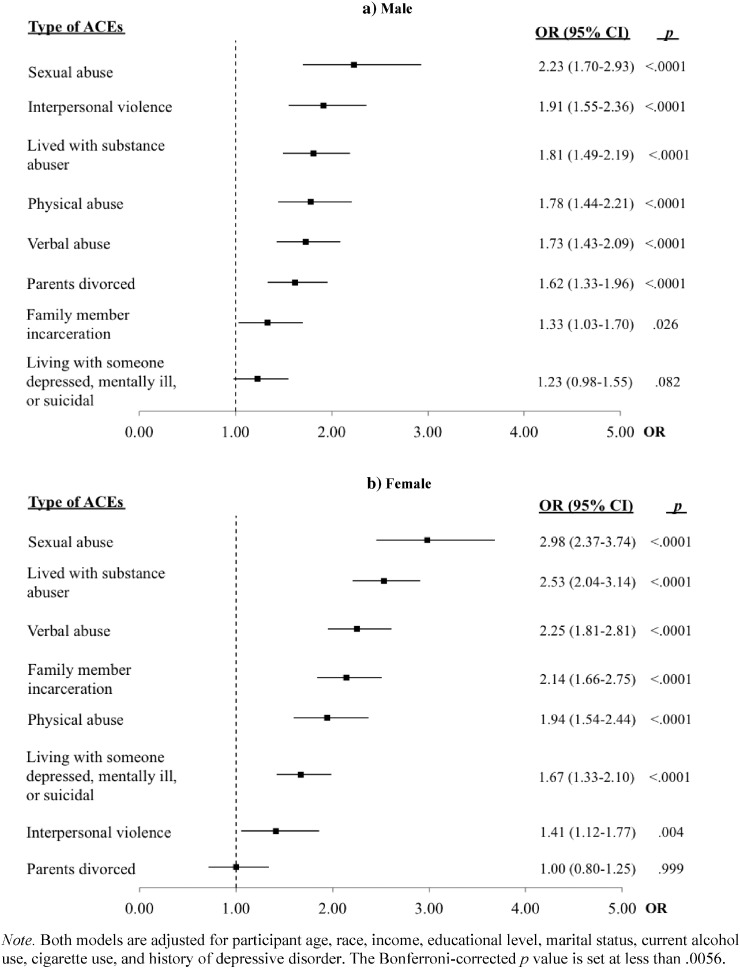

The associations between exposure to different types of ACEs and engaging in HIV risk behaviors between males and females are shown in Fig. 1. After adjusting for socio-demographic characteristics, adult alcohol and cigarette use, and mental health status, the odds of engaging in HIV risk behavior for males are the highest among those who experienced childhood sexual abuse (OR = 2.23), followed by childhood exposure to interpersonal violence (OR = 1.91), substance abuse family members (OR = 1.81), physical abuse (OR = 1.78), verbal abuse (OR = 1.73), and parental divorce (OR = 1.62). Household mental illness and incarceration are not significantly associated with HIV risk behaviors among males according to the Bonferroni corrected significance values (p < 0.0056). For females, those who experienced childhood sexual abuse also have the highest odds of reporting HIV risk behaviors (OR = 2.98), followed by childhood exposure to living with a family member who abused substances (OR = 2.53), verbal abuse (OR = 2.25), family member incarceration (OR = 2.14), physical abuse (OR = 1.94), and living with someone with mental illness (OR = 1.67), and interpersonal violence (OR = 1.41). Parental separation or divorce is not associated with increased HIV risk behaviors among females.

Fig. 1.

Logistic regression models of different types of ACE as a function of adult HIV risk behaviors by gender

The associations between the number of ACEs and HIV risk behaviors are presented in Table 3. A graded relationship between ACE score and HIV risk behaviors is found, although the relationship varies by gender. Among males, compared to those who never experienced ACE, those with one ACE have 1.94 times the odds of engaging in HIV risk behaviors, those with two ACEs have 2.29 times the odds, those with three ACEs have 3.30 times the odds, and those with four or more ACEs have close to 4 times the odds. Among females, relative to those without a history of ACE, the odds of engaging HIV risk behaviors do not significantly elevate until the individual experienced three or more ACEs — females who experienced three ACEs have 2.26 times the odds, and four or more ACEs have 3.27 times the odds.

Table 3.

Adult HIV risk behaviors by exposure to number of ACEs by gender.

| Male |

Female |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | |

| 0 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | ||

| 1 | 1.94 | 1.42–2.63 | < 0.0001 | 0.88 | 0.59–1.32 | 0.534 |

| 2 | 2.29 | 1.64–3.19 | < 0.0001 | 1.62 | 1.08–2.44 | 0.021 |

| 3 | 3.30 | 2.32–4.69 | < 0.0001 | 2.26 | 1.52–3.35 | < 0.0001 |

| 4 + | 3.95 | 2.91–5.35 | < 0.0001 | 3.27 | 2.36–4.51 | < 0.0001 |

Note. Both models are adjusted for participant age, race, income, educational level, marital status, current alcohol use, cigarette use, and history of depressive disorder. The Bonferroni-corrected p value is set at less than 0.0056.

4. Discussion

Based on a retrospective population data, the study provides timely evidence on the relationships between childhood adversities and adult HIV risk behaviors. Moreover, the study also identifies a few gender-specific patterns. Consistent with epidemiology studies that examine the prevalence of ACEs (Anda et al., 2006, Schussler-Fiorenza Rose et al., 2014), approximately 60% of study participants had experienced at least one ACE and over 10% had experience four or more ACEs. As expected, most of the adverse events tested in the study are associated with increased odds of HIV risk behaviors for both males and females, and the odds elevate in a stepwise manner as the number of ACEs rises, suggesting that growing up in a family environment tainted by abuses and distressing events may predispose individuals to HIV risk behaviors.

Gender differences are observed in few instances. Similar to the findings of a previous study (Hillis et al., 2000), growing up with a family member who has mental illness and having a family member who was incarcerated are linked with increased odds of HIV risk behaviors for females, but not for males. Studies have documented intergenerational trauma (Hancock et al., 2013). More research should be conducted to tease out a possible gender effect in the intergenerational transmission of trauma and HIV risks. If the histories of family mental illness and incarceration are more likely to act as an initiator or promotor of poor sexual health outcomes for females, more attention should be given to childhood adversities and family dysfunction when treating female service users.

In contrast, parental divorce or separation raises the likelihood of HIV risk behaviors for males, but it bears no relationship to females after other demographic variables and personal mental health and substance abuse histories are controlled. The negative, long-term consequences of divorce on children have been documented (Kim, 2011, Amato, 2001, Strohschein, 2005). While some studies indicate that the adverse effects of parental divorce are greater for male children than for female children (Morrison and Cherlin, 1995), others suggest the impacts of parental divorce are similar for both (Strohschein, 2005). Future research is needed to unpack the differential behavioral patterns according to gender.

Previous studies detected a mechanism by which ACEs might impact STD and HIV-related risk behaviors in later life. Some researchers have found that self-efficacy (Sales et al., 2008, Raiford et al., 2007, Brown et al., 2014), balanced power relationship (Raiford et al., 2007, Brown et al., 2014), and risky romantic relationships (Wilson and Widom, 2011) can mediate the relationship between ACEs and HIV risk behaviors, but drug use (Wilson and Widom, 2011) and affective symptoms (Wilson and Widom, 2011) do not exert the same mediation effect. Notably, while some studies focus on females only (Sales et al., 2008, Raiford et al., 2007, Brown et al., 2014), others (Wilson and Widom, 2011) focus on the entire population without providing gender specific results. Future studies need to further understand the mechanisms through which ACEs have an impact on later health behaviors by gender. Such knowledge can facilitate the development of gender-specific interventions that help negate the hurtful long-term impact of childhood trauma.

Results from the cumulative ACE models suggested that the odds of HIV risk behaviors increased for males as long as they had one ACE. However, for females, the odds did not increase until they had experienced three or more ACEs. Several explanations may be relevant to the different results between genders observed in the study. First, for women, it is possible that certain combinations of adverse experiences, rather than individual form of ACE, are driving increased odds of HIV risks. Second, there may be a gendered, coping strategy that comes into play. Previous research has discussed that stress coping is linked with traditional gender roles (Al-Bahrani et al., 2013, Matud, 2004). Traditional gender perspectives prescribe females as dependent and emotional, and males as independent and rational (Green and Diaz, 2008). Such perception may affect coping strategies where females use emotion-focused strategies more than males to cope with stressful family events, while males focused on rational and detachment strategies to tackle stressful family events. The differential coping strategies between males and females may mediate the relationships between childhood exposure to adverse events and adult HIV risk behaviors where emotion-focused coping results in more positive adaptation over time than the detachment strategy (Green and Diaz, 2008).

Moreover, receiving support from friends, family, and community is a key protective mechanism against psychological distress (Risser et al., 2010) and sexual risk (Ramiro et al., 2013). Females may have more resources and social support than males to deal with their psychological distress (Dalgard et al., 2006, Shumaker and Hill, 1991). In our study, we found that females have significantly greater odds of engaging in HIV risk behaviors only when they experienced three or more ACEs. It is possible that females have more social support and resources than males, and such support functions as a deterrent in the experiences of childhood adversities.

5. Study limitations

The study has several limitations. First, study findings are drawn from five states that are predominately rural and are in the Midwest or South, which may potentially limit the study's generalizability. Second, underreporting might happen as participants self-reported their exposure to adverse events and HIV risk behaviors. Third, BRFSS does not ask questions concerning participant's sexual orientation. As such, it is not possible to study gender differences beyond that female and male dichotomy. Fourth, the HIV risk behavior variable was measured by one question that combined four types of distinct behaviors (i.e. used intravenous drugs, treated for a STD, received money for sex, and had anal sex without a condom). We were unable to conduct separate analysis that examines the association between ACE and individual risk behavior. Lastly, the information about when the HIV risk behaviors occurred was not available. Therefore, we could not determine if such behaviors took place before, overlapped with, or after the onset of the ACEs. However, given that all of these adverse events took place during childhood, it is probable that the engagement of HIV risk behaviors happened following the occurrence of ACEs (Hillis et al., 2000).

6. Conclusions

The study contributes to the emerging literature on childhood traumatic experiences and HIV risk behaviors. Child abuse and family dysfunctions are shown to be strongly associated with HIV risk behaviors in adulthood. Most of the HIV/AIDS prevention programs focus on reducing these risk behaviors through early testing, behavioral interventions, and community education and outreach (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013). Interventions have not yet focused on psychological risks such as childhood adversities. Building on previous literature on childhood trauma and adult health behaviors (Ramiro et al., 2010, Mersky et al., 2013, Fuller-Thomson et al., 2013, Brennan et al., 2007), our study demonstrates a strong association between ACEs and HIV risk behaviors. We argue that at minimum, service providers and agencies should adopt a trauma-informed lens, understand the prevalence of trauma and its longstanding detrimental effects on an individual's physical, psychological and emotional wellbeing, and provide responsive care accordingly. Trauma-informed care cultivates safety at all levels, and promotes an environment where service users can regain a sense of control and empowerment (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014). Such a service philosophy, together with evidence-based HIV/AIDS prevention strategies, can potentially offer sensitive and effective programs that help curb the HIV endemic.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Afifi T.O., Enns M.W., Cox B.J., Asmundson G.J., Stein M.B., Sareen J. Population attributable fractions of psychiatric disorders and suicide ideation and attempts associated with adverse childhood experiences. Am. J. Public Health. 2008;98(5):946–952. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.120253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Bahrani M., Aldhafri S., Alkharusi H., Kazem A., Alzubiadi A. Age and gender differences in coping style across various problems: Omani adolescents' perspective. J. Adolesc. 2013;36(2):303–309. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato P.R. Children of divorce in the 1990s: an update of the Amato and Keith (1991) meta-analysis. J. Fam. Psychol. 2001;15(3):355–370. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anda R.F., Felitti V.J., Bremner J.D. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2006;256(3):174–186. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anda R.F., Brown D.W., Dube S.R., Bremner J.D., Felitti V.J., Giles W.H. Adverse childhood experiences and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008;34(5):396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland J.M., Altman D.G. Multiple significance tests: the Bonferroni method. BMJ. 1995;310(6973):170. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6973.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan D.J., Hellerstedt W.L., Ross M.W., Welles S.L. History of childhood sexual abuse and HIV risk behaviors in homosexual and bisexual men. Am. J. Public Health. 2007;97(6):1107–1112. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.071423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown L.K., Tolou-Shams M., Lescano C. Depressive symptoms as a predictor of sexual risk among African American adolescents and young adults. J. Adolesc. Health. 2006;39(3):e1–e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.01.015. (444) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D.W., Anda R.F., Tiemeier H. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of premature mortality. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009;37(5):389–396. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D., Anda R., Felitti V. Adverse childhood experiences are associated with the risk of lung cancer: a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J.L., Young A.M., Sales J.M., DiClemente R.J., Rose E.S., Wingood G.M. Impact of abuse history on adolescent African American women's current HIV/STD-associated behaviors and psychosocial mediators of HIV/STD risk. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma. 2014;23(2):151–167. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2014.873511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh C.E., Petras H., Martins S.S. Gender-specific profiles of adverse childhood experiences, past year mental and substance use disorders, and their associations among a national sample of adults in the United States. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2015;50(8):1257–1266. doi: 10.1007/s00127-015-1024-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease and Prevention . Overview: BRFSS 2012. Centers for Disease and Prevention; Washington, DC: 2013. Behavioral risk factor surveillance system. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease and Prevention . Centers for Disease and Prevention; Washington, DC: 2013. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System: Module Data for Analysis for 2012 BRFSS. (July 15, 2013) [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, Sexual Transmitted Diseases and Tuberculosis Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013. Effective behavioral interventions. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data—United States and 6 dependent areas—2012. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report 2014 2014;19(3).

- Cronholm P.F., Forke C.M., Wade R. Adverse childhood experiences: expanding the concept of adversity. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2015;49(3):354–361. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgard O.S., Dowrick C., Lehtinen V. Negative life events, social support and gender difference in depression. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2006;41(6):444–451. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz R.M., Ayala G., Bein E. Sexual risk as an outcome of social oppression: data from a probability sample of Latino gay men in three U.S. cities. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2004;10(3):255–267. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.10.3.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente R.J., Wingood G.M., Crosby R.A. A prospective study of psychological distress and sexual risk behavior among black adolescent females. Pediatrics. 2001;108(5) doi: 10.1542/peds.108.5.e85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente R.J., Crittenden C.P., Rose E. Psychosocial predictors of HIV-associated sexual behaviors and the efficacy of prevention interventions in adolescents at-risk for HIV infection: what works and what doesn't work? Psychosom. Med. 2008;70(5):598–605. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181775edb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube S.R., Anda R.F., Felitti V.J., Edwards V.J., Croft J.B. Adverse childhood experiences and personal alcohol abuse as an adult. Addict. Behav. 2002;27(5):713–725. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube S.R., Anda R.F., Whitfield C.L. Long-term consequences of childhood sexual abuse by gender of victim. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005;28(5):430–438. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube S.R., Fairweather D., Pearson W.S., Felitti V.J., Anda R.F., Croft J.B. Cumulative childhood stress and autoimmune diseases in adults. Psychosom. Med. 2009;71(2):243–250. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181907888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkington K., Bauermeister J., Zimmerman M. Psychological distress, substance use, and HIV/STI risk behaviors among youth. J. Youth Adolesc. 2010;39(5):514–527. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9524-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti V.J., Anda R.F., Nordenberg D. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998;14(4):245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Thomson E., Filippelli J., Lue-Crisostomo C.A. Gender-specific association between childhood adversities and smoking in adulthood: findings from a population-based study. Public Health. 2013;127(5):449–460. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green D.L., Diaz N. Gender differences in coping with victimization. Brief. Treat. Crisis Interv. 2008;8(2):195–203. [Google Scholar]

- Haatainen K.M., Tanskanen A., Kylma J. Gender differences in the association of adult hopelessness with adverse childhood experiences. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2003;38(1):12–17. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0598-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallfors D.D., Waller M.W., Ford C.A., Halpern C.T., Brodish P.H., Iritani B. Adolescent depression and suicide risk: association with sex and drug behavior. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2004;27(3):224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock K., Mitrou F., Shipley M., Lawrence D., Zubrick S. A three generation study of the mental health relationships between grandparents, parents and children. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13(1):299. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis S.D., Anda R.F., Felitti V.J., Nordenberg D., Marchbanks P.A. Adverse childhood experiences and sexually transmitted diseases in men and women: a retrospective study. Pediatrics. 2000;106(1) doi: 10.1542/peds.106.1.e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis S.D., Anda R.F., Felitti V.J., Marchbanks P.A. Adverse childhood experiences and sexual risk behaviors in women: a retrospective cohort study. Fam. Plan. Perspect. 2001;33(5):206–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM SPSS Inc. SPSS, Inc.; Chicago, IL: 2015. SPSS 23.0 for Windows. [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.S. Consequences of parental divorce for child development. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2011;76(3):487–511. [Google Scholar]

- Kouyoumdjian F.G., Findlay N., Schwandt M., Calzavara L.M. A systematic review of the relationships between intimate partner violence and HIV/AIDS. PLoS One. 2013;8(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matud M.P. Gender differences in stress and coping styles. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2004;37(7):1401–1415. [Google Scholar]

- McGowan J.P., Shah S.S., Ganea C.E. Risk behavior for transmission of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) among HIV-seropositive individuals in an urban setting. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004;38(1):122–127. doi: 10.1086/380128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mersky J.P., Topitzes J., Reynolds A.J. Impacts of adverse childhood experiences on health, mental health, and substance use in early adulthood: a cohort study of an urban, minority sample in the U.S. Child Abuse Negl. 2013;37(11):917–925. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messina N., Marinelli-Casey P., Hillhouse M., Rawson R., Hunter J., Ang A. Childhood adverse events and methamphetamine use among men and women. J. Psychoactive Drugs. 2008;(Suppl. 5):399–409. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2008.10400667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison D.R., Cherlin A.J. The divorce process and young children's well-being: a prospective analysis. J. Marriage Fam. 1995;57(3):800–812. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick M., O'Malley P., Johnston L., Terry-McElrath Y., Schulenberg J. HIV/AIDS risk behaviors and substance use by young adults in the United States. Prev. Sci. 2012;13(5):532–538. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0279-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettes T., Kerr T., Voon P., Nguyen P., Wood E., Hayashi K. Depression and sexual risk behaviours among people who inject drugs: a gender-based analysis. Sex. Health. 2015 doi: 10.1071/SH14200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiford J.L., Wingood G.M., DiClemente R.J. Correlates of consistent condom use among HIV-positive African American women. Women Health. 2007;46(2–3):41–58. doi: 10.1300/J013v46n02_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramiro L.S., Madrid B.J., Brown D.W. Adverse childhood experiences (ACE) and health-risk behaviors among adults in a developing country setting. Child Abuse Negl. 2010;34(11):842–855. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramiro M.T., Teva I., Bermúdez M.P., Buela-Casal G. Social support, self-esteem and depression: relationship with risk for sexually transmitted infections/HIV transmission. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2013;13(3):181–188. [Google Scholar]

- Remigio-Baker R., Hayes D., Reyes-Salvail F. Adverse childhood events are related to the prevalence of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder among adult women in Hawaii. Lung. 2015;1-7 doi: 10.1007/s00408-015-9777-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risser J., Cates A., Rehman H., Risser W. Gender differences in social support and depression among injection drug users in Houston, Texas. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36(1):18–24. doi: 10.3109/00952990903544802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Wright C.P., Olate R., Vaughn M.G. Substance use, violence, and HIV risk behavior in El Salvador and the United States: cross-national profiles of the SAVA syndemic. Vict. Offenders. 2015;10(1):95–116. [Google Scholar]

- Sales J., Salazar L.F., Wingood G.M., DiClemente R.J., Rose E., Crosby R.A. The mediating role of partner communication skills on HIV/STD–associated risk behaviors in young African American females with a history of sexual violence. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2008;162(5):432–438. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.5.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling E.A., Aseltine R.H., Gore S. Adverse childhood experiences and mental health in young adults: a longitudinal survey. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schussler-Fiorenza Rose S.M., Xie D., Stineman M. Adverse childhood experiences and disability in U.S. adults. Pm r. 2014;6(8):670–680. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senn T.E., Carey M.P., Vanable P.A. Childhood and adolescent sexual abuse and subsequent sexual risk behavior: evidence from controlled studies, methodological critique, and suggestions for research. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2008;28(5):711–735. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumaker S.A., Hill D.R. Gender differences in social support and physical health. Health Psychol. 1991;10(2):102–111. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.10.2.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St. Lawrence J., Brasfield T., Jefferson K., Allyene E., Shirley A. Social support as a factor in African-American adolescents' sexual risk behavior. J. Adolesc. Res. 1994;9(3):292–310. [Google Scholar]

- Strohschein L. Parental divorce and child mental health trajectories. J. Marriage Fam. 2005;67(5):1286–1300. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse, Mental Health Services Administration . Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2014. SAMHSA's Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. [Google Scholar]

- van der Meer L.B., van Duijn E., Wolterbeek R., Tibben A. Adverse childhood experiences of persons at risk for Huntington's disease or BRCA1/2 hereditary breast/ovarian cancer. Clin. Genet. 2012;81(1):18–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whetten K., Reif S., Toth M., Jain E., Leserman J., Pence B.W. Relationship between trauma and high-risk behavior among HIV-positive men who do not have sex with men (MDSM) AIDS Care. 2012;24(11):1453–1460. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.712665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson H.W., Widom C.S. Pathways from childhood abuse and neglect to HIV-risk sexual behavior in middle adulthood. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2011;79(2):236–246. doi: 10.1037/a0022915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]