Abstract

Background: Radical cystectomy (RC) carries a high complication rate, including post-operative ileus. Alvimopan is an FDA approved peripherally acting μ-opioid receptor antagonist that has shown favorable results for improved recovery of gastro-intestinal function resulting in decreased hospital length of stay. Many enhanced recovery pathways (ERP) have been published demonstrating improved outcomes with decreased hospital stay and morbidity.

Objective: We evaluated the addition of alvimopan to an ERP in patients undergoing RC.

Methods: Patients undergoing RC at our institution during the implementation phase of alvimopan to our established ERP were retrospectively reviewed. Effect of alvimopan as it related to the use of nasogastric tubes, time to initiation of regular diet, and length of hospital stay was assessed using Chi-squared and Student’s T-tests. Linear regression was performed for univariate analysis and binary logistic regression was performed as a multivariate assessment of the effect of alvimopan.

Results: Between July 2011 and January 2013, 80 patients were identified who underwent RC under the ERP (34 alvimopan and 46 standard care). Age, sex, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, surgical technique (open vs. robotic), and type of urinary diversion were not different between groups. Alvimopan was associated with a reduction in mean time to regular diet (5.3 vs 4.1 days, p < 0.01) and a reduction in mean length of hospital stay (6.9 vs 5.7 days, p = 0.01). After controlling for other variables, alvimopan usage predicted for shorter time to regular diet and total hospital stay.

Conclusions: Alvimopan may help to improve time to regular diet and decrease hospital stay in patients on an enhanced recovery pathway.

Keywords: Bladder cancer, radical cystectomy, alvimopan, enhanced recovery pathway

INTRODUCTION

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by radical cystectomy (RC) is considered the gold standard for muscle invasive and locally advanced bladder cancer [1, 2]. RC is a major operation with a high rate of post-operative morbidity. In fact, complications and hospital readmission rates are reported as high as 60% in surgical series [3–5]. One of the biggest challenges in management is the treatment of post-operative ileus and the reinitiation of enteral feeding [6]. In addition to the morbidity of nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain, increased hospital length also adds to the total cost of care [7, 8]. Causes of post-operative ileus are likely a comprehensive response to surgical manipulation of tissue, disruption of anatomy, inflammation, neuropathic reflexes and opioid use. Alvimopan is a peripherally acting μ-opioid receptor antagonist that has been shown to improve gastrointestinal function and decrease hospital stay in a randomized controlled trial in patients undergoing RC [9].

Recently, post-operative pathways, known as enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) or enhanced recovery pathways (ERP), have been developed and studied to improve outcomes. These surgical pathways optimize patient care, advance gastrointestinal recovery, and decrease hospital length of stay [10, 11]. While ERPs vary in their implementation, they generally involve the avoidance of bowel preparation prior to surgery, allow a regular diet up to the night before surgery, minimize intraoperative and post-operative fluid administration, avoid routine nasogastric tube placement, encourage early ambulation, initiate early oral feeding, and encourage the judicious use of epidurals and anti-inflammatory medications to avoid narcotic administration. However, the use of promotility agents or other bowel medications has not been standardized and remains variable.

It is clear that an ERP improves patient outcomes following surgery, specifically RC [12]. Furthermore, alvimopan has been demonstrated in clinical trials to decrease time to gastrointestinal recovery and length of hospital stay [9]. Our aim was to evaluate the addition of alvimopan to an established ERP for radical cystectomy in patients with bladder cancer to determine if there is incremental improvement in return of gastrointestinal motility and length of hospital stay. To our knowledge, no studies have addressed this specifically.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

After IRB approval (HSC Study 1328), we performed a retrospective chart review of patients who underwent radical cystectomy, pelvic lymph node dissection, and urinary diversion between July 2011 and January 2013 at the University of Kansas Medical Center. Patients who underwent both robot-assisted procedures and open radical cystectomies were included in this analysis. Patients underwent ileal conduit or orthotopic neobladder urinary diversion at the discretion of the surgeon and patient. All urinary diversions were performed extracorporally. In addition to RC, all patients underwent an extended lymph node dissection as described by Bochner and Herr [13]. Board certified pathologists performed tumor staging according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer’s AJCC Cancer Staging Manual [14].

The RC post-operative pathway during the dates of this analysis was standardized as our institution’s enhanced recovery pathway (ERP) and was adhered to by all physicians performing RC. Specifically,no patients underwent a bowel preparation prior to surgery and were allowed to eat a regular diet up to the night before surgery. Patients were given peri-operative ketorolac on post-operative day one if the renal function was in the normal range. Epidurals were regularly offered and utilized based on a discussion between the patient and anesthesiologist. Epidural medications consisted of bupivacaine and hydromorphone, unless restricted by patient allergies. If an epidural was not placed, then a patient-controlled anesthesia pump (PCA) was used, and fentanyl or morphine was provided as a first option. Both epidural and PCA were offered to patients, regardless of alvimopan use. Nasogastric tubes were not utilized during or following surgery unless indicated by symptoms. Pain was controlled with an epidural or a PCA until resumption of a regular diet at which time they were transitioned to oral pain medications, regardless of alvimopan group. Oral opioids consisted of oxycodone/acetaminophen, unless limited by allergies or adverse side effects, and escalated to higher doses if patients reported poor pain control that limited mobility. Early and aggressive ambulation was encouraged through a directed effort by the nursing staff, the house staff and surgeons. A limited clear liquid diet was initiated post-operatively, unrestricted clear liquids were started on post-operative day 2, and advanced to a regular diet with return of bowel activity (passage of gas or bowel movement). Upon tolerance of a regular diet, ureteral stents and drains were removed and patients were discharged. Patients were offered to be discharged to home with a local home health nursing agency to provide routine in-home visits every 1–3 days. If patients or their families requested, skilled nursing facilities or rehabilitation centers were arranged as well.

Beginning in July 2011, alvimopan was offered to patients undergoing radical cystectomy. Usage of alvimopan was left up to the discretion of the attending surgeon and the patient preference at the time. Patients were informed of a new medication that had shown promise regarding enhanced bowel recovery after cystectomy; however, given that it was not a part of our standard pathway, medication usage was ultimately left up to the patient. Patients were excluded if they had taken therapeutic doses of opioids for more than seven consecutive days prior to surgery, according to manufacturer guidelines. Patients received the first dose orally (12 mg) in the pre-operative bay and continued dosing every 12 hours until return of bowel function. The University of Kansas Medical Center is registered in the Entereg Access Support and Education (EASE) program. This is a program provided by the manufacturer of alvimopan and ensures adequate educational materials are given to patients and providers and that administration guidelines are followed.

We charted baseline demographics including age, sex, race, receipt of chemotherapy, stage, type of surgery (robotic or open), and type of diversion (conduit or neobladder). Patients were grouped based on the receipt of alvimopan, with those not receiving alvimopan serving as controls. Chi-squared analysis and Student’s T-tests were utilized to compare all categorical and continuous variables between groups in order to assess for baseline differences between groups. Additionally, the strength of association of these variables were assessed against the primary outcomes (time to initiation of regular diet and length of stay) using Student’s T-tests and linear regression. An additional sensitivity analysis was performed for the effect of alvimopan excluding patients with narcotics listed on their medical records.

A binary logistic regression analysis of all independent variables versus the primary outcome variables was performed to control for potential confounding interactions. In order to complete this analysis, the primary outcomes of time to regular diet and length of stay were converted into binary outcomes in which the target outcome was defined as less than or equal to the median time to regular diet and length of stay for the Alvimopan group. Statistics were performed using SPSS 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York) with p-values reported for 2-sided analyses.

RESULTS

Eighty patients met inclusion criteria and make up the cohort for our analysis. Of these, 34 (42.5% ) patients were treated with alvimopan peri-operatively and 46 (57.5% ) did not. At baseline (see Table 1), there were no significant differences in age, race, gender, receipt of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, type of surgery (open versus robotic), type of diversion (ileal conduit versus neobladder), or stage. Patients receiving alvimopan had a trend towards a reduced rate of nasogastric tube decompression (15.2% vs 2.9% , p = 0.07).

Table 1.

Baseline features and comparison of outcomes between groups

| Alvimopan | Control | p-value | |

| N | 34 | 46 | – |

| Age (Range) | 68.8 (44–92) | 69.2 (57–84) | 0.84 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 28 (82.4) | 29 (63.0) | |

| Female | 6 (17.6) | 5 (10.9) | 0.07 |

| Race | |||

| White | 33 (97.1) | 45 (97.8) | |

| African American | 1 (2.9) | 1 (2.2) | 0.84 |

| Neoadjuvant | 16 (47.1) | 24 (52.2) | 0.65 |

| Chemotherapy | |||

| Surgery Type | |||

| Open | 16 (47.1) | 25 (54.3) | |

| Robotic | 18 (52.9) | 21 (45.7) | 0.52 |

| Diversion | |||

| Ileal Conduit | 22 (64.7) | 34 (73.9) | |

| Neobladder | 12 (35.3) | 12 (26.1) | 0.37 |

| Stage | |||

| pT0 | 3 (8.8) | 8 (17.4) | |

| pTa/pTis/pT1 | 9 (26.5) | 12 (26.1) | |

| pT2 | 6 (17.6) | 7 (15.2) | |

| pT3 | 11 (32.4) | 10 (21.7) | |

| pT4 | 5 (14.7) | 9 (19.3) | 0.70 |

| pN+ | 6 (17.6) | 10 (21.7) | 0.65 |

| Nasogastric Tube Use | 1 (2.9) | 7 (15.2) | 0.07 |

| Time to Regular | 4.0, 4.05 | 5.0, 5.26 | 0.007 |

| Diet, median, | (3.0–5.0) | (3.75–6.0) | |

| mean (days, IQR) | |||

| LOS, median, | 5.0, 5.65 | 6.0, 6.84 | 0.01 |

| mean (days, IQR) | (5.0–6.0) | (5.0–8.0) |

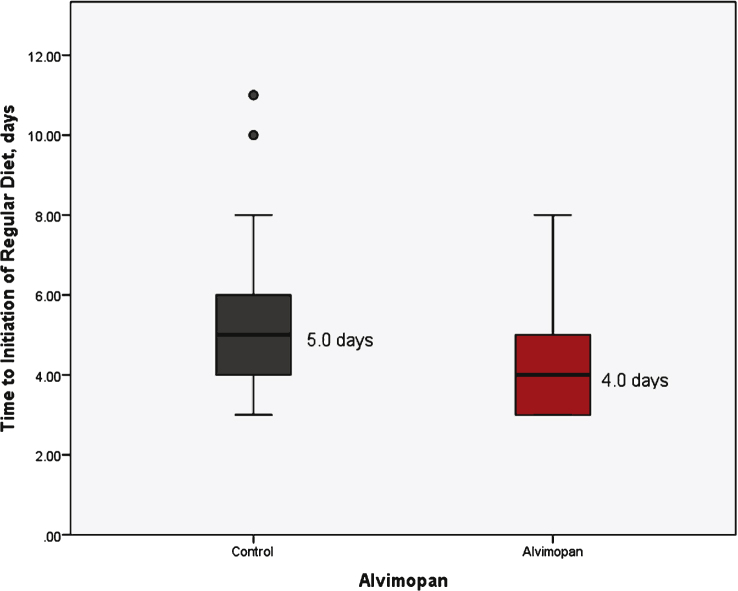

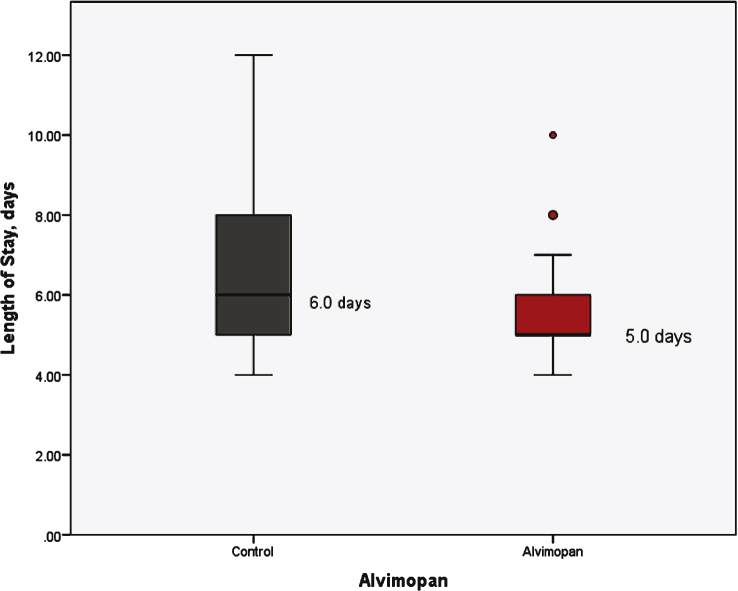

With respect to the primary outcomes measured, the receipt of alvimopan was associated with a reduction in mean time to regular diet (5.3 vs 4.1 day, p < 0.01) and a reduction in mean length of hospital stay (6.9 vs 5.7 days, p = 0.01) (Table 1). Figure 1 demonstrates a box plot narrative of the median and interquartile range of the control and alvimopan group in regards to time to regular diet. Similarly, total length of stay is demonstrated in Fig. 2. Linear regression analysis was used to assess each individual factor against the primary outcome of time to regular diet and length of hospital stay. Only alvimopan usage was statistically significant with a mean decrease of 1.2 days for both endpoints (–1.2 days, 95% CI: –2.7, –0.3, p < 0.01) and (–1.2 days, 95% CI: –2.1, –0.3, p = 0.01), respectively (Table 2). Further, sensitivity analysis was performed after excluding patients with narcotics listed on their medical record (11 patients total). Time to regular diet (4.0 days for alvimopan vs 5.2 days for control, p < 0.01) and length of stay (5.7 days for alvimopan vs 6.9 days for control, p = 0.01) remained significant.

Fig.1.

Time to initiation of regular diet stratified by treatment group.

Fig.2.

Length of stay stratified by treatment group.

Table 2.

Effect of clinical features on time to regular diet and length of stay

| Difference in Time to Regular Diet (95% CI) | p-value | Difference in Length of Stay (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Alvimopan v Control | –1.2 (–2.7, –0.3) | <0.01 | –1.2 (–2.1, –0.3) | 0.01 |

| Age (≥65 v <65) † | 0.3 (–0.7, 1.3) | 0.58 | 0.5 (–1.1, 1.0) | 0.95 |

| Male v Female | 0.1 (–1.0, 1.2) | 0.85 | –0.2 (–1.3, 0.9) | 0.72 |

| White v Black | 0.8 (–2.1, 3.6) | 0.60 | 1.4 (–1.6, 4.3) | 0.36 |

| Robotic v Open | –0.2 (–1.1, 0.7) | 0.72 | –0.3 (–1.2, 0.6) | 0.51 |

| Conduit v Neobladder | 0.1 (–0.9, 1.1) | 0.81 | 0.3 (–0.7, 1.3) | 0.55 |

| Chemotherapy v no Chemotherapy | –0.5 (–1.3, 0.4) | 0.32 | –0.68 (–1.6, 0.2) | 0.15 |

| Pathologic Stage (≤pT2 v >pT2) | 0.7 (–0.2, 1.6) | 0.14 | 0.4 (–0.5, 1.3) | 0.40 |

| Nodal Status (pN0 v pN+) | 0.5 (–0.6, 1.7) | 0.33 | 0.9 (–0.3, 2.0) | 0.13 |

All values are mean. †Bivariate correlation of Age was non-significant (Spearman’s Rho = 0.11, p = 0.34).

The median time to initiation of regular diet (4.0 days) and length of stay (5.0 days) were utilized as the value for each metric in conversion to a binary outcome. Using binary logistic regression analyses, the effect of alvimopan was maintained when controlled for all other measured variables. The receipt of alvimopan was associated with an OR of 3.81 (95% CI: 1.40–10.36, p < 0.01) for initiation of regular diet within 4 days and an OR of 2.98 (95% CI: 1.09–8.20, p = 0.03) for a length of stay less than 5 days when compared to the control. Interestingly, node positivity and female gender was associated with higher odds of increased time to regular diet and overall hospital stay, respectively (Table 3). There were no bowel related hospital readmissions within thirty days in either group (data not shown). Furthermore, no patients required discontinuation of alvimopan due to adverse effects of the drug.

Table 3.

Multivariable † assessment of primary outcomes, significant\\ predictors of outcome

| OR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Time to Regular Diet | |||

| Alvimopan | 3.81 | 1.40–10.36 | <0.01 |

| pN+ | 0.20 | 0.05–0.82 | 0.03 |

| Length of Stay | |||

| Alvimopan | 2.98 | 1.09–8.20 | 0.03 |

| Female Gender | 0.06 | 0.005–0.79 | 0.03 |

†Variables assessed: Age, Receipt of Alvimopan, Gender, Race, Stage, Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy, Surgery Type, and Diversion.

DISCUSSION

Alvimopan has clearly been shown to improve outcomes in the surgical literature, and more specifically, in the radical cystectomy population. Lee et al. conducted a multi-institutional, randomized trial involving twenty-one academic institutions. A total of 277 patients were included, and the alvimopan cohort experienced quicker return of bowel function (5.5 vs 6.8 days; p < 0.0001) and shorter mean length of hospitalization (7.4 vs 10.1 days; p < 0.01) [9]. Similarly, Vora et al reviewed a cohort of eighty patients utilizing alvimopan. They similarly noted a quicker time to hospital discharge (6.1 vs 7.7 days, p = 0.04) [15]. These data clearly demonstrate the advantages of alvimopan in this particular patient population.

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols are evidence-based surgical pathways designed to optimize perioperative outcomes for patients that undergo complex surgery. These ERAS protocols were first introduced for patients undergoing colorectal surgery and included reduced preoperative fasting and early postoperative feeding [16]. Overall, goals of ERAS pathways are to decrease total hospital length of stay, decrease complications, and reduce readmission rates. The key principles of the ERAS protocol include pre-operative counseling, preoperative nutrition, avoidance of perioperative fasting and bowel preparation, standardized anesthetic and analgesic regimens (epidural and non-opioid analgesia), early mobilization, avoidance of NGT, early initiation of diet, and aggressive post-operative bowel regimens [11]. Morbidity after RC can be as high as 30–64% [17], thus RC patients are considered to be ideal candidates for an ERAS pathway. Several recent publications have suggested ERAS protocols for RC patients as especially beneficial [12, 18].

Our goal was to evaluate whether the addition of alvimopan to an established enhanced recovery pathway (ERP) would result in an incremental improvement in usage of nasogastric tubes, time to regular diet, and time to discharge home. Despite many groups using alvimopan as part of their ERP, we are not aware of any analyses to show the benefit as we have in this report. Clearly, postoperative ileus is a common cause of prolonged hospitalization after radical cystectomy and intuitively interventions to decrease the rate would subsequently decrease length of stay. As mentioned, this was demonstrated in the randomized controlled trial of alvimopan in radical cystectomy [9]. Interesting to note, the time to diet in the control group was 6.8 days and the mean length of hospitalization was 10.1 days, both of which were considerably longer than in our population (5.3 and 6.9, respectively). It is obvious that multiple post-operative pathways were utilized in this trial and practice patterns were varied. Despite the fact that our cohort of patients had reduced time to diet and decreased length of stay, we still found an improvement with the usage of alvimopan.

Given the shortening of hospital stay, the usage of the drug also subsequently decreases hospital cost. Kauf et al. determined the decreased hospitalization cost was secondary to decreased post-operative ileus and hospital stay [19]. Other groups have similarly demonstrated improved cost benefit even up to $1515 per hospitalization [15, 20]. Furthermore, the usage of alvimopan has proven to be safe in patients undergoing bowel surgery [21, 22]. This was confirmed in our study as no patients required discontinuation of drug due to adverse effects or events. Also, the thirty-day readmission rates between the two groups did not differ (data not shown).

We acknowledge that there are several limitations to our study. First, the decision to administer alvimopan was influenced by several factors that may not be captured in a retrospective chart review. A selection bias may exist in the patients who receive or did not receive alvimopan. While a matched case-control approach would have reduced this bias, our cohort was not large enough to allow matching. As such, we performed our multivariable analysis with all potential predictors in an attempt to reduce the potential selection bias. The rigor of this approach may be questioned, however the magnitude of the effect of alvimopan on the primary outcomes in the multivariable analysis would suggest that the effect seen on univariate analysis is real.

Furthermore, it is worth noting that only 42.5% of our cohort was in the alvimopan group. Given that we did not provide a pre-treatment questionnaire to assess patient opinions, we are unsure why more patients did not opt for the medication. One possibility is that patients hesitated to be the first to try a new medication at our institution. During pre-operative counseling, patients were informed that the medication was new to our regimen and taking the medication was optional as we began incorporating it into our pathway, thus they may not have been comfortable with this medication that was unknown to our institution. Second, we were unable to objectively quantify post-operative narcotic usage. Certainly, a bias towards more narcotic usage in the non-Alvimopan group is possible, however, all patients were given the choice of epidural or PCA and every patients was initiated on oral narcotic medication when tolerating regular diet regardless of the receipt of Alvimopan. Third, our cohort of patients is small and all underwent surgery at one academic medical center. Therefore, our results may not be representative of the general population of patients undergoing radical cystectomy in other regions of the country or outside of academic medical centers. Fourth, the established ERP at our institution has variations based on unforeseen patient factors; however, we feel that those differences would be similar in both groups. Despite these limitations, we feel that this report does give evidence that alvimopan should be considered as an adjunct to an established ERP.

CONCLUSION

Alvimopan has been demonstrated to improve time to regular diet and time to discharge in patients undergoing radical cystectomy in several studies. In addition, the adoption of an ERP has shown similar benefits throughout the literature. We have demonstrated that the addition of alvimopan to an ERP may result in additional improvements in time to regular diet, time to discharge, and decreased hospital costs without increases in complications or readmissions. Therefore, consideration should be given to adding this to established ERP protocols.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grossman HB, Natale RB, Tangen CM, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus cystectomy compared with cystectomy alone for locally advanced bladder cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:859–866. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Collaboration ABCAM-a: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in invasive bladder cancer: Update of a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data advanced bladder cancer (ABC) meta-analysis collaboration. European Urology 2005;48:202-5. discussion 205-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Lowrance WT, Rumohr JA, Chang SS, et al. Contemporary open radical cystectomy: Analysis of perioperative outcomes. The Journal of Urology. 1313;179:1318–1318. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.11.084. discussion 1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donat SM, Shabsigh A, Savage C, et al. Potential impact of postoperative early complications on the timing of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients undergoing radical cystectomy: A high-volume tertiary cancer center experience. European Urology. 2009;55:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stimson CJ, Chang SS, Barocas DA, et al. Early and late perioperative outcomes following radical cystectomy: 90-day readmissions, morbidity and mortality in a contemporary series. The Journal of Urology. 2010;184:1296–1300. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang SS, Baumgartner RG, Wells N, et al. Causes of increased hospital stay after radical cystectomy in a clinical pathway setting. The Journal of Urology. 2002;167:208–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doorly MG, Senagore AJ. Pathogenesis and clinical and economic consequences of postoperative ileus. The Surgical Clinics of North America. 2012;92:259–272. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2012.01.010. viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kariv Y, Wang W, Senagore AJ, et al. Multivariable analysis of factors associated with hospital readmission after intestinal surgery. American Journal of Surgery. 2006;191:364–371. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee CT, Chang SS, Kamat AM, et al. Alvimopan accelerates gastrointestinal recovery after radical cystectomy: A multicenter randomized placebo-controlled trial. European Urology. 2014;66:265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pruthi RS, Nielsen M, Smith A, et al. Fast track program in patients undergoing radical cystectomy: Results in 362 consecutive patients. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2010;210:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Melnyk M, Casey RG, Black P, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols: Time to change practice?Canadian Urological Association Journal=Journal de l’Association des Urologues du Canada. 2011;5:342–348. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.11002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cerantola Y, Valerio M, Persson B, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care after radical cystectomy for bladder cancer: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS((R))) society recommendations. Clinical Nutrition. 2013;32:879–887. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bochner BH, Herr HW, Reuter VE. Impact of separate versus en bloc pelvic lymph node dissection on the number of lymph nodes retrieved in cystectomy specimens. The Journal of Urology. 2001;166:2295–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: The 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2010;17:1471–1474. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0985-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vora A, Marchalik D, Nissim H, et al. Multi-institutional outcomes and cost effectiveness of using alvimopan to lower gastrointestinal morbidity after cystectomy and urinary diversion. The Canadian Journal of Urology. 2014;21:7222–7227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roulin D, Donadini A, Gander S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of the implementation of an enhanced recovery protocol for colorectal surgery. The British Journal of Surgery. 2013;100:1108–1114. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shabsigh A, Korets R, Vora KC, et al. Defining early morbidity of radical cystectomy for patients with bladder cancer using a standardized reporting methodology. European Urology. 2009;55:164–174. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daneshmand S, Ahmadi H, Schuckman AK, et al. Enhanced recovery protocol after radical cystectomy for bladder cancer. The Journal of urology. 2014;192:50–55. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.01.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kauf TL, Svatek RS, Amiel G, et al. Alvimopan, a peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonist, is associated with reduced costs after radical cystectomy: Economic analysis of a phase 4 randomized, controlled trial. The Journal of Urology. 2014;191:1721–1727. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hilton WM, Lotan Y, Parekh DJ, et al. Alvimopan for prevention of postoperative paralytic ileus in radical cystectomy patients: A cost-effectiveness analysis. BJU International. 2013;111:1054–1060. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kehlet H, Holte K. Review of postoperative ileus. American Journal of Surgery. 2001;182:3S–10S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00781-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buchler MW, Seiler CM, Monson JR, et al. Clinical trial: Alvimopan for the management of post-operative ileus after abdominal surgery: Results of an international randomized, double-blind, multicentre, placebo-controlled clinical study. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2008;28:312–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]