Abstract

Asexual development (conidiation) in the filamentous fungus Aspergillus nidulans is governed by orchestrated gene expression. The three key negative regulators of conidiation SfgA, VosA, and NsdD act at different control point in the developmental genetic cascade. Here, we have revealed that NsdD is a key repressor affecting the quantity of asexual spores in Aspergillus. Moreover, nullifying both nsdD and vosA results in abundant formation of the development specific structure conidiophores even at 12 h of liquid culture, and near constitutive activation of conidiation, indicating that acquisition of developmental competence involves the removal of negative regulation exerted by both NsdD and VosA. NsdD’s role in repressing conidiation is conserved in other aspergilli, as deleting nsdD causes enhanced and precocious activation of conidiation in Aspergillus fumigatus or Aspergillus flavus. In vivo NsdD-DNA interaction analyses identify three NsdD binding regions in the promoter of the essential activator of conidiation brlA, indicating a direct repressive role of NsdD in conidiation. Importantly, loss of flbC or flbD encoding upstream activators of brlA in the absence of nsdD results in delayed activation of brlA, suggesting distinct positive roles of FlbC and FlbD in conidiation. A genetic model depicting regulation of conidiation in A. nidulans is presented.

Asexual development (conidiation) in the fungal class Ascomycetes results in the formation of mitotically derived conidiospores, or conidia1. Despite a great variety in conidial form and function, all conidia represent non-motile asexual propagules that are usually made from the side or tip of specialized sporogenous cells, i.e., phialides in Aspergillus, via asymmetric mitotic cell division1.

The genetic mechanisms of conidiation have been extensively studied in the model fungus Aspergillus nidulans. In a simple way, the A. nidulans asexual reproductive cycle can be divided into four distinct stages, beginning with a growth phase, proceeding through initiation of the developmental pathway, execution of the developmentally regulated events leading to sporogenesis, and concluding with switching off conidiation by feed-back control2. The growth phase involves germination of a conidium and formation of an undifferentiated network of interconnected hyphal cells that form the mycelium. After a certain period of vegetative growth, under appropriate conditions, some of the hyphal cells stop normal growth and begin conidiation by forming complex structures called conidiophores that bear multiple chains of conidia (Fig. 1A; reviewed in ref. 1).

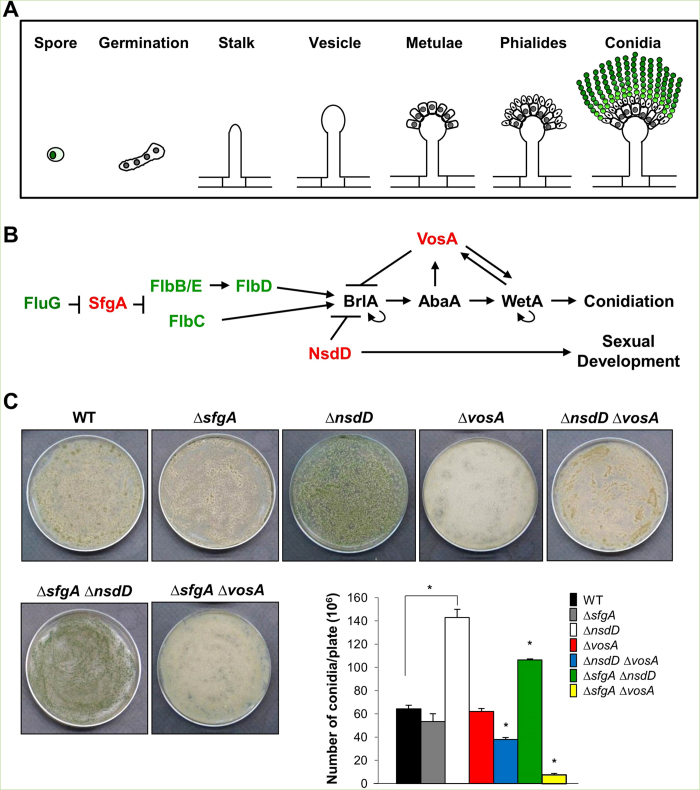

Figure 1. Background information and quantitative analyses of conidiation.

(A) A schematic presentation of development of conidiophore in A. nidulans. (B) A genetic model for developmental regulation. Greens are activators and reds are repressors of brlA. (C) Conidiation levels in WT and various mutants. About 105 conidia of WT (FGSC4), ΔsfgA (TNJ57), ΔnsdD (TNJ108), ΔvosA (THS15), ΔnsdD ΔvosA (TMK11), ΔsfgA ΔnsdD (TMK5), and ΔsfgA Δvos (TMK10) strains were spread on solid MMG and grown for 2 days and the numbers of conidia per plate were counted in triplicates (*P < 0.001).

Conidiation does not usually occur in A. nidulans until cells have gone through a defined period of vegetative growth necessary for cells to acquire the ability to respond to development signals, which is defined as a competence3. Under normal media conditions, A. nidulans can be maintained in the vegetative stage of its life cycle by growing hyphae submerged in liquid medium. In liquid submerged culture, conidiation hardly takes place and sexual fruiting never occurs unless vegetative cells are exposed to air. Previous studies have revealed that A. nidulans cells require approximately 18 h of growth before they are competent to respond to the inductive signal provided by exposure to air3,4.

A key event responding to the developmental inductive signal is activation of brlA, which encodes a C2H2 zinc finger transcription factor (TF) (Fig. 1B)5. Further genetic and biochemical studies have identified the abaA and wetA genes as necessary regulators of conidiation. The abaA gene encodes a putative TF that is activated by brlA during the middle stages of conidiophore development after differentiation of metulae6,7. The wetA gene, activated by AbaA, functions in late phase of conidiation for the synthesis of crucial cell wall components and conidial metabolic remodeling8,9. These three genes have been proposed to define a central regulatory pathway that acts in concert with other genes to control conidiation-specific gene expression and determine the sequence of gene activation during conidiophore development and spore maturation10,11,12 (reviewed in ref. 1).

Subsequent studies have identified various upstream developmental activators (UDAs), fluG, flbA, flbB, flbC, flbD, and flbE that influence brlA expression (Fig. 1B)13,14,15. Mutations in any of these genes result in “fluffy” colonies that are characterized by undifferentiated cotton-like masses of vegetative cells (reviewed in ref. 1). Each of the FlbB, FlbC and FlbD proteins contains a DNA binding domain and they are shown to be direct activators of brlA expression16,17. The two genetic cascades composed of fluG →→ flbE/flbB→ flbD → brlA, and fluG →→ flbC → brlA were proposed, in which fluG functions upstream18.

Our studies to further understand the developmental control mechanisms have identified three key negative regulators of conidiation, SfgA, VosA, and NsdD19,20,21. The fluG suppressor sfgA is predicted to encode a Zn(II)2Cys6 domain protein, and positioned between FluG and FLBs (Fig. 1B)16,22. The velvet domain TF VosA and the GATA-type TF NsdD were isolated via gain-of-function genetic screens as repressors of conidiation19,21. VosA, which is activated by AbaA, governs spore maturation and exerts negative feedback regulation of brlA by binding to the 11 nucleotide VosA responsive element (VRE) in the brlAβ promoter19,23. NsdD, initially identified as a key activator of sexual fruiting24, was found to be also a key repressor of conidiation21. The deletion of nsdD bypasses the needs for FluG and all UDAs, but not brlA, for conidiation, indicating that NsdD acts downstream of UDAs and upstream or at the same level of brlA25.

In the present study, we further investigate negative regulation of conidiation and developmental competence. Through combinatorial genetic studies, we have found that VosA and NsdD are the major factors repressing brlA expression, and thereby influencing the acquisition of developmental competence in A. nidulans. We also report that the repressive role of NsdD in conidiation is conserved in other aspergilli. In A. nidulans conidia, NsdD directly binds to the brlAβ promoter region, which contains a GATAA sequence potentially interacting with NsdD. We also demonstrate that FlbC and FlbD are necessary for full activation of brlA even in the absence of nsdD. A working genetic model depicting the positive and negative regulations of brlA expression and conidiation in A. nidulans is presented.

Results

NsdD is a key factor determining the number of conidia

Previously, we showed that vosA and nsdD play an additive role in repressing conidiation and brlA expression in vegetative cells21. To further expand our understanding on the genetic interactions of the three negative regulators, we generated double mutants: ∆nsdD ∆vosA, ∆sfgA ∆nsdD and ∆sfgA ∆vosA. We then quantified the conidiation levels of FGSC4 (wild type; WT), ∆sfgA, ∆nsdD, ∆vosA, ∆nsdD ∆vosA, ∆sfgA ∆nsdD and ∆sfgA ∆vosA strains by spreading conidia onto solid MMG and incubating for 2 days. As shown in Fig. 1C, the ∆nsdD mutant produced ~2.3 fold more conidia than WT and other mutant strains (p < 0.001). The ∆sfgA ∆nsdD double mutant produced less number of conidia than the ∆nsdD single mutant, but more than WT (p < 0.001). On the contrary, the ∆sfgA ∆vosA mutant produced a highly reduced number of conidia, ~6 fold less than WT and the ∆vosA mutant. The ∆nsdD ∆vosA double mutant produced a similar number of conidia to WT. These results suggest that NsdD is a major determinant of the number of conidia being produced on solid culture condition. The ∆sfgA ∆vosA mutant exhibited a highly reduced number of conidia than each single mutant, suggesting that the ∆sfgA and ∆vosA mutations have synthetic negative effects on conidiogenesis.

NsdD and VosA cooperatively repress brlA expression and conidiation

One approach to investigate elevated or hyper activation of conidiation is to grow the strains in liquid shake culture and check conidiophore development and mRNA levels of brlA. Under this condition, WT hardly ever produces asexual developmental structure. When WT, ∆nsdD, ∆vosA, ∆sfgA, ∆sfgA ∆vosA, ∆sfgA ∆nsdD and ∆nsdD ∆vosA strains were examined at 16 h liquid shake culture, only the ∆nsdD ∆vosA double mutant formed a high number of conidiophores (Fig. 2A). We then examined the mRNA levels of brlA, abaA and wetA in WT and various mutant strains at 16 h of vegetative growth, and found that only the ΔnsdD ΔvosA double mutant showed a high level accumulation of brlA mRNA (Fig. 2B). Accumulation of abaA and wetA mRNA was consistent with the brlA mRNA expression pattern in the ΔnsdD ΔvosA mutant. These led us to determine the levels of brlA mRNA in WT, ΔnsdD, ΔvosA, and ΔnsdD ΔvosA strains in conidia and very early phases of growth (4~16 h of liquid culture). As shown in Fig. 2C, the ΔvosA mutant displayed a high level of brlA mRNA in conidia and somewhat reduced levels of brlA mRNA in vegetative cells, lacking further activation of brlA expression. On the contrary, the ΔnsdD ΔvosA mutant exhibited a high level of brlA mRNA in conidia, and began to show induced activation of brlA expression even at 6 h of liquid culture, and a sudden strong activation of brlA expression at 10 h and thereafter. In fact, the ΔnsdD ΔvosA mutant formed conidiophores as early as 12 h of liquid culture (data now shown). These findings indicate that NsdD and VosA are major negative regulators of brlA expression and conidiation, and that the removal of the repressive effects imposed by NsdD and VosA might be a key factor determining the developmental competence.

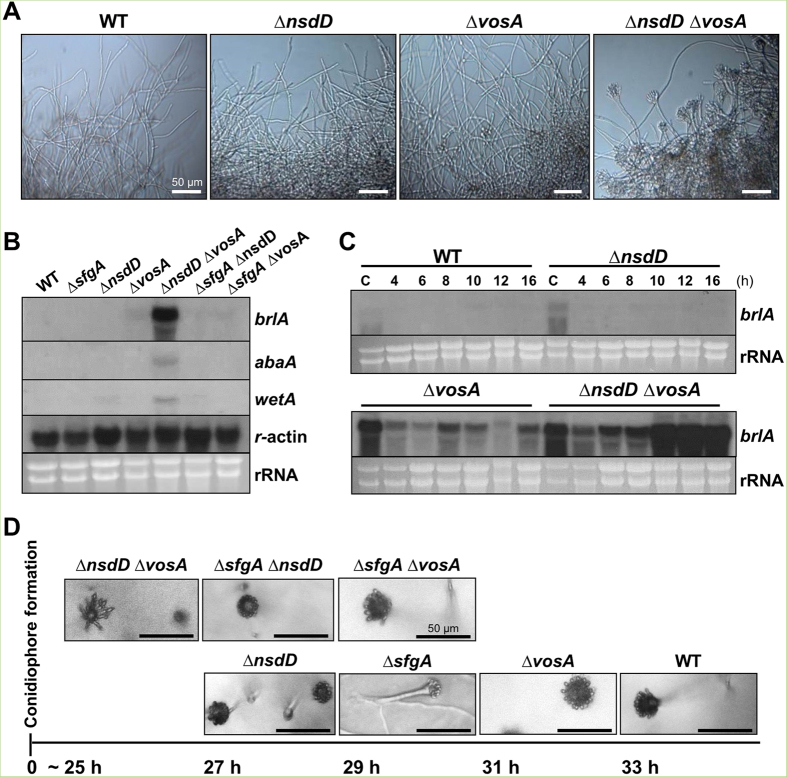

Figure 2. Accelerated conidiation by the lack of vosA and nsdD.

(A) Photographs of WT (FGSC4), ΔnsdD (TNJ108), ΔvosA (THS15) and ΔnsdD ΔvosA (TMK11) hyphae at 16 h in liquid MMG. (Bar = 50 μm). (B) Levels of brlA, abaA, and wetA mRNA in designated strain grown in liquid submerged culture for 16 h. The γ-actin gene was used as a control. (C) Levels of brlA mRNA in WT, Δnsd, ΔvosA and ΔnsdD ΔvosA strains in liquid submerged culture up to 16 h. C = conidia. (D) Time needed for the formation of the first conidiophore in single colonies of WT (FGSC4), ΔnsdD (TNJ108), ΔvosA (THS15), ΔsfgA (TNJ57), ΔsfgA ΔnsdD (TMK5), ΔsfgA ΔvosA (TMK10), and ΔnsdD ΔvosA (TMK11) on solid MMG. Photographs were taken at indicated time when the first conidiophore was visible. Numbers indicate the incubation time (h) after streak on solid MMG.

We also check timing of conidiation on solid air-exposed culture condition. Somewhat consistent with the above findings, the time required for the first conidiophore formation in a colony derived from a single conidium on solid medium was about 25 h in the ΔnsdD ΔvosA mutant (Fig. 2D). The ΔsfgA ΔnsdD and ΔnsdD mutants showed initial conidiophore development at 27 h. The ΔsfgA ΔvosA and ΔsfgA mutants formed the first conidiophore at 29 h. The ΔvosA showed elaboration of conidiophore at ~31 h, whereas WT formed the first conidiophore at 33 h. These results suggest collectively that negative regulation of brlA by both NsdD and VosA is a key attribute determining the developmental competence.

NsdD represses conidiation in A. flavus and A. fumigatus

All Aspergillus species appear to have an ortholog of NsdD (AspGD; http://www.aspgd.org/). The predicted NsdD polypeptide, especially the GATA domain in the C-terminus, is highly conserved in A. flavus and A. fumigatus (Fig. 3A). We hypothesized that NsdD might play a similar repressive role in conidiation in these aspergilli.

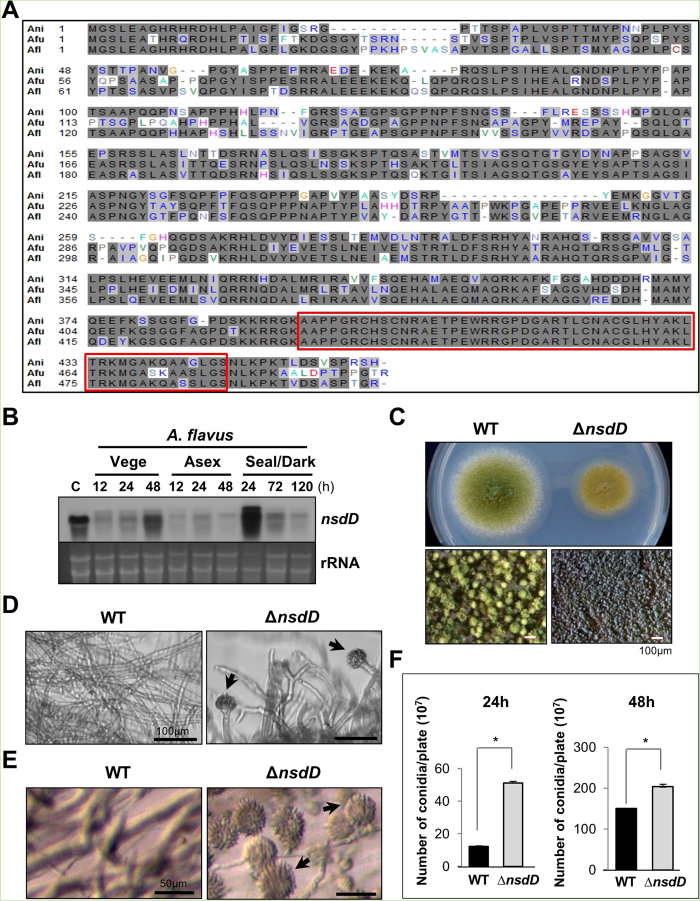

Figure 3. Characterization of nsdD in A. flavus.

(A) Alignment the NsdD proteins of A. fumigatus (Afu3g13870), A. flavus (AFL2T_03635), and A. nidulans (AN3152). The red box indicates the highly conserved region. (B) Levels of nsdD mRNA during the lifecycle of A. flavus WT (NRRL3357). C = Conidia. The time (h) of incubation in liquid submerged culture (Vege), post asexual induction (Asex), and sealed/dark condition (Seal/Dark) is shown. Equal loading of total RNA was confirmed by ethidium bromide staining of rRNA. (C) Phenotypes of A. flavus WT and ΔnsdD (LNJ11) strains point inoculated on solid MMG with 0.1% yeast extract (YE) and incubated at 30 °C for 3 days. Close-up views (lower panel) of the center of individual colonies. (Bar = 100 μm). (D) Cells of A. flavus WT and ΔnsdD strains in liquid submerged culture grown for 28 h. Note the abundant formation of conidiophores in ΔnsdD strain (Bar = 100 μm). Conidiophore is marked by arrowhead. (E) Agar-embedded cells of A. flavus WT and ΔnsdD strains grown on solid MMG for 28 h. Abundant formation of conidiophores in ΔnsdD strain is evident. (Bar = 50 μm). (F) Quantitative analyses of conidiation in A. flavus WT and ΔnsdD strains. About 105 conidia were spread on solid MMG with 0.1% YE, incubated for 24 and 48 h, and the conidia numbers per plate were counted in triplicates (*P < 0.001).

In A. flavus, nsdD mRNA levels are high in conidia, and undulate during the lifecycle (Fig. 3B). The deletion of nsdD in A. flavus by replacing its coding region with the pyrG+ marker from A. fumigatus, caused restricted colony growth coupled with abnormal conidiophores compared to WT (NRRL3357; Fig. 3C). The size of the ∆nsdD conidiophores was averaged 45.81 μm, whereas WT conidiophore size was averaged 125.6 μm (P < 0.005; data not shown). This is consistent with the previous report demonstrating that NsdD is a major determinant of developmental morphogenesis26. We then examined levels of conidiation in varying ways, and found that the absence of nsdD resulted in hyper-active conidiation evidenced by the elaboration of a high number of conidiophores at 28 h of liquid shake culture (Fig. 3D), the formation of abundant conidiophores imbedded in agar at 28 h of solid culture (Fig. 3E), as well as enhanced production of conidia per plate (Fig. 3F). These results indicate that NsdD is a key repressor of conidiation in A. flavus.

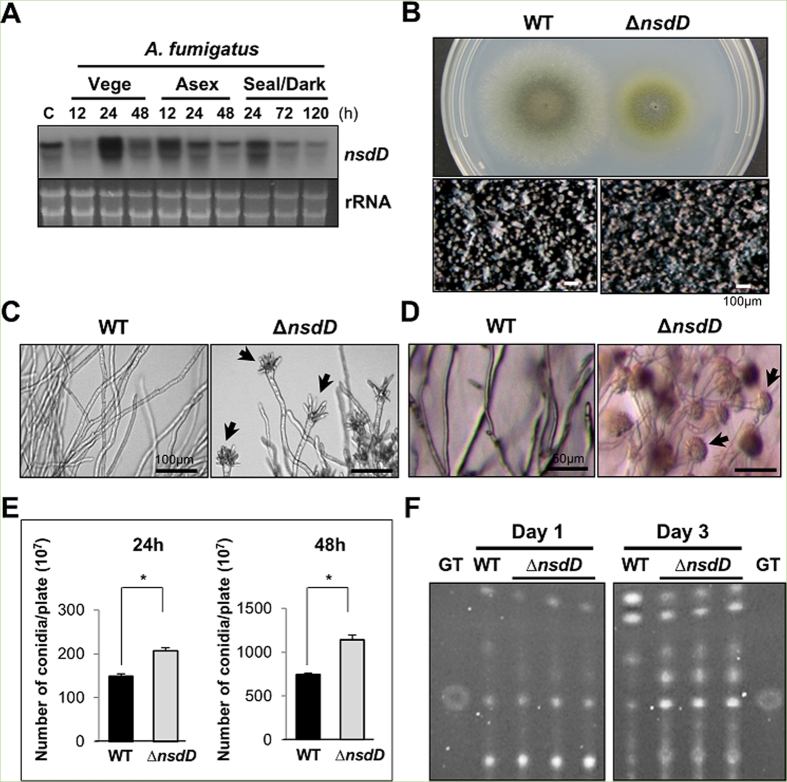

In A. fumigatus, nsdD is somewhat constitutively expressed, and its mRNA levels are high in conidia (Fig. 4A). Similar to A. nidulans and A. flavus, the deletion of nsdD in A. fumigatus caused restricted hyphal growth (Fig. 4B), and early and uncontrolled activation of conidiation leading to the formation of conidiophores at 19 h liquid shake culture (Fig. 4C), and elaboration of a high number of conidiophores imbedded in agar at 28 h of solid culture (Fig. 4D), and enhanced production of conidia per plate (Fig. 4E). As the mycotoxin gliotoxin (GT) biosynthesis is activated by BrlA25,27, the deletion of nsdD resulted in elevated production of GT (Fig. 4F). These results indicate that NsdD functions as a negative regulator of conidiation and GT production in the opportunistic human pathogen A. fumigatus.

Figure 4. Characterization of nsdD in A. fumigatus.

(A) Levels of nsdD mRNA during the life cycle of A. fumigatus WT (AFU293). C = conidia. See Fig. 3B legend for the times. Equal loading of total RNA was confirmed by ethidium bromide staining of rRNA. (B) Phenotypes of A. fumigatus WT and ΔnsdD (FNJ19) strain point inoculated on solid MMG with 0.1% YE and incubated at 37 °C for 3 days. Close-up views (lower panel) of the center of the colonies are shown (Bar = 100 μm). (C) Cells of A. fumigatus WT and ΔnsdD strains grown in liquid submerged culture for 19 h (Bar = 100 μm). Note abundant formation of aberrant conidiophores in the mutant. Conidiophore is marked by arrowhead. (D) Agar-embedded cells of A. fumigatus WT and ΔnsdD strains grown on solid MMG for 27 h (Bar = 50 μm). A high number of conidiophores was evident. (E) Quantitative analysis of conidiation: 105 spores of WT and ΔnsdD strains were spread on solid MMG with 0.1% YE, incubated for 24 and 48 h, and the conidia numbers per plate were counted in triplicates (*P < 0.001). (F) Thin-layer chromatogram of CHCl3 extracts of A. fumigatus WT and ΔnsdD strains grown in liquid MMG with 0.5% YE for 1 and 3 days (stationary culture). Gliotoxin standard (GT) is shown.

NsdD directly binds to the brlAβ promoter region

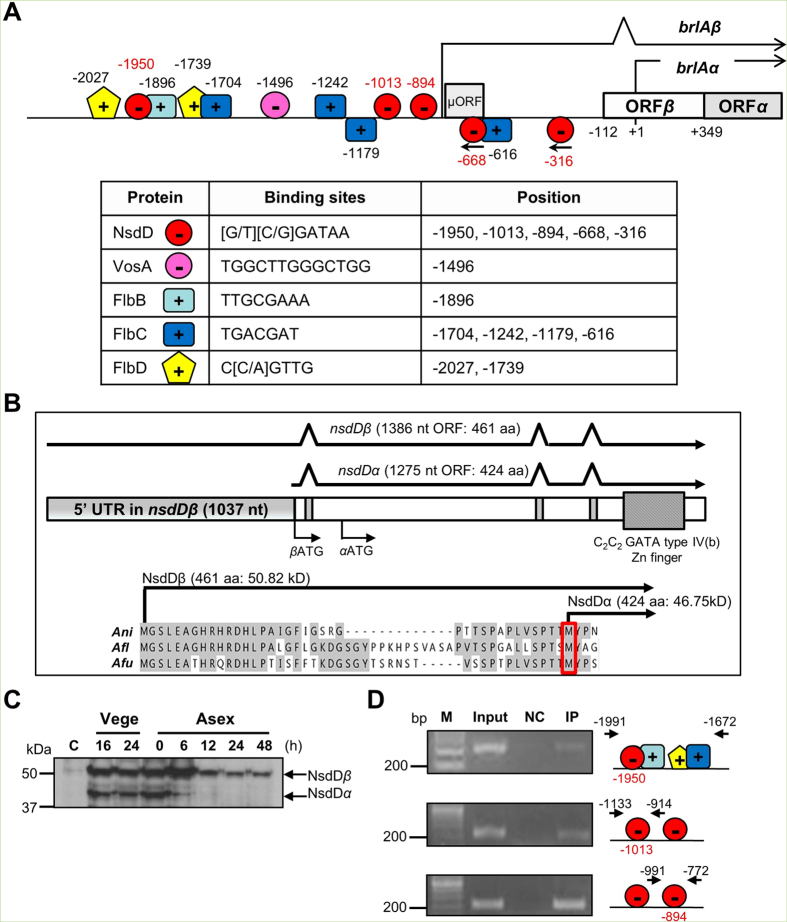

We previously reported that, in the FluG-mediated conidiation pathway, NsdD functions downstream of FlbE/B/D/C and upstream of brlA21. In a simplistic interpretation, we hypothesized that NsdD directly binds to upstream of the brlA coding sequence. To test this hypothesis, we first scanned the brlA promoter region spanning 2 kb with JASPAR CORE database (http://jaspar.genereg.net) to search potential GATA-TF binding sites. NsdD contains a zinc finger GATA binding domain at 394th–446th amino acid at its C-terminus, which may interact with a core [A/T]GATA[A/G] consensus sequence. As shown in Fig. 5A, we identified five core GATA sequences located at the −1950 (+), −1013 (+), −894 (+), −668 (−), and −316 (−) nucleotide, where the transcription initiation site for brlAα is designated as +1 5. Binding sites of VosA, FlbB, FlbC, and FlbD in the brlAβ promoter are also marked in Fig. 5A 16,17,23.

Figure 5. Regulatory elements of brlA and interaction of NsdD with the brlA upstream region.

(A) A schematic diagram showing the binding regions (sequences) of VosA, FlbB, FlbC, and FlbD, and the putative GATA regions for NsdD. The brlAα transcription start site is denoted as “+1”. Hence, the BrlAβ and BrlAα translational start ATGs are at “−112” and “+349”, respectively. (B) Summary of the nsdD locus encoding two polypeptides. Gene structure was verified by sequence analyses of various cDNAs of nsdD. Start codon is assigned as ‘βATG’ and ‘αATG’. The predicted NsdDα polypeptide lacks the first 37 aa present in NsdDβ. (C) Western blot analysis of NsdDβ (~51 kDa) and NsdDα (~46 kDa) using anti-FLAG antibody and the TMK 13 strain. C = Conidia. Numbers indicate the time (h) of incubation in liquid submerged culture (Vege) and post asexual developmental induction (Asex). (D) Verification of NsdD binding to the brlA promoter by ChIP-PCR. The NsdD-ChIP was performed with 2 day-old conidia of TMK13. The PCR amplicons were separated on a 2% agarose gel. The chromatin sample before immuno-precipitation (IP) was used as a positive control (Input). The chromatin sample being incubated with beads alone without anti-FLAG antibody was used as a negative control (NC). Representative results and positions of each primer pair for PCR amplification are shown.

Our previous study revealed that nsdD encodes two distinct transcripts designated as nsdDβ and nsdDα21. The nsdDα transcript specifically accumulates in conidia, whereas the nsdDβ constitutively accumulates throughout the lifecycle. Specific expression of nsdDα in conidia requires activity of both VosA and VelB during the formation of spores23. The nsdDβ and nsdDα transcripts contain 1,037 nt and 150 nt of 5′ untranslated region (UTR), respectively (Fig. 5B). Further analyses of cDNAs by RT-PCR indicate that these transcripts are predicted to encode the NsdDβ (461aa) and NsdDα (424aa) polypeptides, where NsdDα lacks the first 37 aa found in NsdDβ. To check the presence and expression levels of the predicted two NsdD proteins during the lifecycle, we carried out Western blot analysis employing a strain ectopically expressing NsdD::3XFLAG in ΔnsdD (TMK13, Table 1) and anti-FLAG antibody. We found that levels of both the NsdDβ and NsdDα proteins were very low in conidia, high in vegetative cells, then NsdDα became undetectable at 6 h post developmental induction (Fig. 5C). Employing the TMK13 strain and anti-FLAG antibody, we pulled-down the NsdD interacting DNAs in conidia, and PCR-amplified the five regions containing a core GATA site in the brlA promoter (ChIP-PCR). As shown in Fig. 5A,D, the three regions spanning −1,950, −1,013, and −894 containing the GATAA sequence in the + strand gave rise amplicons. However, the two regions containing GATAA in the − strand were not enriched by NsdD-ChIP. Taken together, while the precise NsdD binding sequence should be identified and validated, multiple NsdD might occupy the brlAβ promoter region. It can be further proposed that binding of NsdD and VosA to the brlA promoter results in the full repressive control of brlA expression, and the developmental competence might be determined by the removal of these key direct negative regulators of brlA (see Discussion).

Table 1. Aspergillus strains used in this study.

| Strain name | Relevant genotype | References |

|---|---|---|

| FGSC4 | A. nidulans wild type | FGSCb |

| RJMP1.59 | pyrG89; pyroA4 | 58 |

| TNJ36 | pyrG89; AfupyrG+; pyroA4 | 22 |

| THS15 | pyrG89; pyroA4; ΔvosA::AfupyrG+ | 34 |

| TNJ57 | pyrG89; ΔsfgA::AfupyrG+; pyroA4 | 45 |

| TNJ108 | pyrG89; pyroA4; ΔnsdD::AfupyrG+ | 21 |

| TNJ176 | pyrG89; pyroA4; ΔnsdD::pyroA+; ΔflbC::AfupyrG+ | 21 |

| TNJ178 | pyrG89; pyroA4; ΔnsdD::pyroA+; ΔflbD::AfupyrG+ | 21 |

| TMK5 | pyrG89; ΔsfgA::AfupyrG+; pyroA4; ΔnsdD::pyroA+ | This study |

| TMK10 | pyrG89; ΔsfgA::pyroA+; pyroA4; ΔvosA::AfupyrG+ | This study |

| TMK11 | pyrG89; pyroA4; ΔnsdD::pyroA+; ΔvosA::AfupyrG+ | This study |

| TMK13 | pyrG89; 3/4pyroA4::nsdD(p)::nsdD::FLAG3X::trpC(t)::pyroA+c; ΔnsdD::AfupyrG+ | This study |

| NRRL3357 | A. flavus wild type | FGSCb |

| NRRL3357.5 | AflpyrG− | 54 |

| LNJ11 | AflpyrG−; ΔnsdD::AfupyrG+ | This study |

| AFU293 | A. fumigatus wild type | 59 |

| AFU293.1 | AfupyrG1− | 55 |

| FNJ19 | AfupyrG1−; ΔnsdD::AnipyrG+ | This study |

aAll A. nidulans strains carry the veA+ allele.

bFungal Genetic Stock Center.

cThe 3/4 pyroA marker restores pyroA+ when it integrates into the pyroA4 locus by a single cross-over.

The positive roles of FlbC and FlbD in conidiation

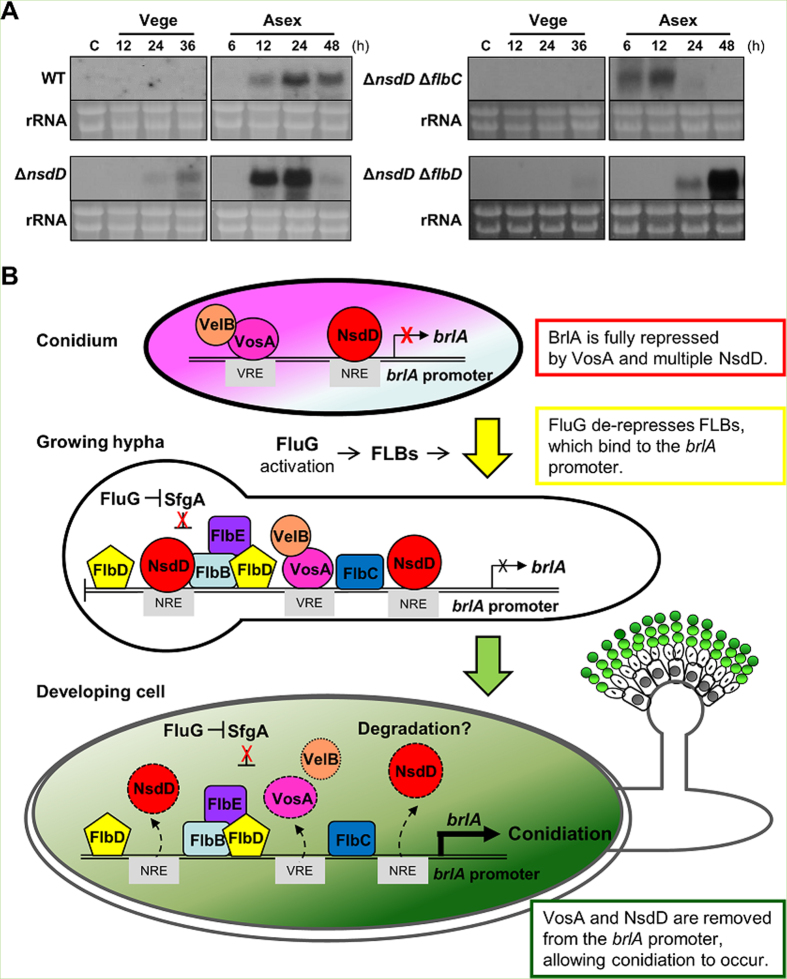

We previously showed that the deletion of nsdD suppressed the conidiation defects caused by the absence of FLBs21. We further asked whether the primary role of FLBs is to remove the NsdD-mediated negative regulation or they play distinct roles in activating conidiation. This was done by determining timing and levels of brlA in the ΔnsdD single and ∆flbC ∆nsdD and ∆flbD ∆nsdD double mutants. As shown in Fig. 6A, brlA accumulation was not observed in WT vegetative conditions, and was slightly increased 12 h post asexual developmental induction. The deletion of nsdD caused brlA mRNA accumulation at 36 h in submerged culture (vegetative), and at high levels at 12 and 24 h post induction. Importantly, we found that, even in the absence of nsdD, the deletion of flbC, or flbD resulted in significantly reduced and delayed accumulation of brlA mRNA at 24 and 48 h post induction. These results indicate that these positive regulators play distinct positive roles in activating brlA expression, and their activities are needed for full activation of brlA.

Figure 6. The role FlbC and FlbD in activating brlA, and a model for regulation of the commencement of conidiation.

(A) Levels of brlA mRNA during the life cycle of WT (FSCG4), ΔnsdD (TNJ108), ΔnsdD ΔflbC (TNJ176) and ΔnsdD ΔflbD (TNJ178) strains are shown. The numbers indicate time (h) of incubation in liquid submerged culture (Vege), and post asexual developmental induction (Asex). C = conidia. Equal loading of total RNA was confirmed by ethidium bromide staining of rRNA. (B) A model depicting the roles of Flbs, VosA, and NsdD in governing the acquisition of developmental competence and the commencement of conidiation (see text).

Discussion

Conidiation in Aspergillus occurs as an integral part of the life cycle primarily controlled by the intrinsic genetic program rather than as a response to unfavorable environmental conditions1. Neither the concentration of a limiting nutrient such as glucose or nitrogen source, nor continuous transfer to new medium modifies the timing with which cells become competent to develop1,28.

Given that the timing of competence acquisition is endogenous and genetically determined, one can ask how the fungus keeps track of the time that has transpired following germination. Timberlake29 came up with an explanation for this by proposing a repressor of conidiation, which becomes diluted during early growth. In this model, a fixed amount of repressor would be produced during the final stages of conidium differentiation and stored in the spore. During the (~18 h of) vegetative growth, such a repressor is diluted to a critical concentration before development can proceed. Timberlake further speculated that it could be a negatively acting TF that prevents expression of genes required for conidiation, e.g., brlA, and mutational inactivation of such a repressor would be expected to lead to precocious development.

Indeed, collectively, our studies have revealed that there are at least three negative regulators of conidiation, and that a key event for the acquisition of developmental competence is to remove the repressive effects imposed by NsdD and VosA. We further have found that the positive upstream regulators are needed for maximum level conidiation, but not for the commencement of development. This is based on the fact that the deletion of nsdD could bypass the need for fluG, flbB, flbE, flbD, and flbC, but not brlA, in conidiation21. Importantly, for the first time, we demonstrated that NsdD physically binds to three different regions in the brlAβ promoter, further supporting the idea that NsdD directly (rather than indirectly) represses the onset of brlAβ expression and conidiation.

NsdD is a GATA TF with a highly conserved DNA-binding domain consisting a Cys2-Cys2 type IV zinc finger in its C-terminal basic region24. GATA TFs (GATA-1 ~ GATA-6) bind to a DNA sequence called a GATA motif [(A/T)GATA(A/G)] present in the regulatory regions of their target genes through two zinc finger domains30. Our in vivo NsdD-DNA interaction analyses in conidia suggest that the NsdD responsive elements (NREs) might be composed of the GATAA core sequence. As shown in Fig. 5, the three regions containing GATAA in the + strand, but not the two regions with GATAA in the − strand, can be enriched by NsdD-ChIP. The GATAA sequence at −1950 is positioned between the predicted binding sites for the two key UDAs, FlbB and FlbD13,17. The two sites at −1013 and −894 may overlap with the RNA polymerase binding region (the brlAβ transcript is marked by the arrow-head line in Fig. 5A). A revised VosA responsive element (VRE; TGGCTTGGGCTGG) is positioned at −1,496 between the two predicted FlbC binding sites16,23. Thus, binding of multiple NsdD and one VosA-VelB in the promoter region of brlAβ may effectively inhibit the initiation of brlAβ transcription. In fact, as shown in Fig. 2A–D, the absence of both nsdD and vosA resulted in near constitutive expression of brlA throughout the life cycle, and abundant/precocious conidiophore development in liquid culture (as early as 12 h). However, the observation that about 25 h is required for the elaboration of the first conidiophore in the ΔnsdD ΔvosA mutant colony derived from a conidium (Fig. 2D) suggests that a single spore must undergo vegetative growth for a certain period even in the absence of the key negative regulators of conidiation.

The NsdD polypeptide(s) is highly conserved in most (if not all) Aspergillus species (Fig. 3A) and other fungi including Penicillium, Coccidioides, Ajellomyces, and Fusarium (not shown). Moreover, the A. fumigatus and A. flavus nsdD genes appear to encode two transcripts (and polypeptides; see the second Met position Fig. 3A,B and 4A). We demonstrated that the role of NsdD in negatively controlling brlA and conidiation is conserved in these two species. In A. fumigatus, there are four GATAA sequences at −2276, −1148, −976, and −932, where the BrlA ATG is +1. In A. flavus, two GATAA sequences are present at −1413 and −1389, where the BrlA ATG is +1. In both cases, the deletion of nsdD resulted in precocious and enhanced conidiation, which is consistent with a previous report31. Early and increased production of GT in the A. fumigatus nsdD mutant can be explained by precocious and enhanced expression of BrlA, which in turn directly activates gliotoxin biosynthesis27,32.

Tight repression of brlA in a conidium and for a certain period of vegetative growth is important for the fitness of Aspergillus fungi. Adams and Timberlake33 showed that overexpression of brlA in vegetative cells resulted in complete cessation of growth and generalized losses of protein and RNA. Collectively, we present a genetic model depicting the negative and positive regulations and the commencement of conidiation in A. nidulans (Fig. 6). During the formation of conidia, VosA and VelB are activated by AbaA34, which in turn activate expression of the lower transcript of nsdD in conidia23. VosA and multiple NsdD are bound to the upstream regulatory region of brlA, which confers full repression of brlA and conidiation. SfgA acts as an upstream negative regulator of conidiation functioning downstream of FluG20. During early phase of vegetative growth, FluG accumulates to a certain level, which then removes the repressive effects of SfgA, thereby allowing UDAs (FlbB/D and FlbC) to function. Acquisition of the developmental competence might also involve the translocation of FlbB to the hyphal tip, became transcriptionally competent, then entering into the nucleus35. In order for activated FlbB-FlbD17 and FlbC to trigger brlA expression and conidiation, both NsdD and VosA need to be removed from the brlA promoter. Currently, we do not know how NsdD and VosA are displaced from the brlA promoter. One possible explanation is degradation of the VosA and NsdD proteins. Upon removal of NsdD and VosA coupled with the cooperative activity of FLBs, brlAβ is expressed above threshold, which then fully activates itself and brlAα, triggering development of conidiophores21. While not shown in the model, activated BrlA leads to expression of AbaA, which in turn activates expression of VosA, VelB, and WetA in phialides and conidia (see Fig. 1B). The VosA-VelB heterodimer shuts off expression of brlA and β-glucan biosynthetic genes, and activates genes associated with trehalose biogenesis and nsdDα in conidia, allowing full repression of brlA for next generation19,34,36.

Finally, while we presented a simplified single-path model for conidiation, it is important to note that that regulation of development is a complex multi-degree process involving both activation of the FluG-initiated conidiation pathway and inhibition of FadA-mediated G protein signaling pathway for vegetative growth37,38,39,40,41. In A. nidulans, various G protein mutants displayed precocious activation of conidiation42,43,44. Moreover, high level accumulation of brlA alone might not be sufficient to trigger conidiation as shown in our ricA study45. In A. fumigatus, various developmental regulators including velvet proteins, G-proteins, and RAS proteins govern conidiation (reviewed in ref. 46 and 47). Additional studies integrating genome-wide and systems analyses are in progress to better address the developmental control mechanisms in Aspergillus.

Methods

Fungal strains and culture conditions

The Aspergillus strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. A. nidulans strains were grown on solid or in liquid minimal medium with 1% glucose (MMG) with supplements as described previously48 at 7 °C. To determine the numbers of conidia in WT and mutant strains, approximately 105 spores were spread onto solid MMG and incubated at 37 °C for 2 days. The conidia were collected from the entire plate and counted using a hemocytometer. To check elaboration of conidiophores in liquid submerged culture, conidia (106/ml) of individual strains were inoculated in liquid MMG and incubated at 37 °C, 220 rpm. For Northern blot analyses, samples were collected as described49. Briefly, for vegetative growth, conidia (106/ml) of strains were inoculated in liquid MMG and cultured at 37 °C, 220 rpm. Samples of liquid submerged culture were collected at designated time points. Induction of asexual development or sexual development was done as described previously49.

A. flavus and A. fumigatus strains were grown on solid or in liquid MMG with 0.1% yeast extract (YE, v/v) and supplements as described48,50, at 30 °C and 37 °C, respectively. To check elaboration of conidiophores in liquid submerged culture, conidia (2 × 105/ml) of individual strains were inoculated in liquid MMG with 0.5% YE and incubated, 220 rpm. For developmental induction, vegetative cells were collected and transferred to solid medium, and the culture plates were air exposed for asexual developmental induction or tightly sealed induction in dark condition as described49.

Construction of A. nidulans strains

The oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Table S1. The double joint PCR (DJ-PCR) method51 was used to generate the ∆sfgA ∆vosA, ∆nsdD ∆vosA and ∆sfgA ∆nsdD mutants. Both 5′ and 3′ flanking regions of the sfgA and nsdD genes were amplified from genomic DNA of FGSC4 using OMK556;OMK557 and OM558;OMK559 (for sfgA), and OMK562;OMK563 and OMK564;OMK565 (for nsdD). The A. nidulans pyroA+ marker was amplified with the primer pair ONK395;ONK396. The final DJ-PCR sfgA deletion construct was amplified with OMK560;OMK561, and the nsdD deletion construct was amplified with OMK566;OMK567. The sfgA deletion amplicon was introduced into THS15.1 to generate the ∆sfgA ∆vosA mutant. The nsdD deletion amplicon was introduced into THS15.1 and TNJ57 to generate the ∆nsdD ∆vosA and ∆sfgA ∆nsdD mutants, respectively. Protoplasts were generated using the Vinoflow FCE lysing enzyme (Novozymes)52. At least three independent deletion mutant strains were isolated. To complement ∆nsdD and epitope-tag NsdD, the FGSC4 nsdD fragment including its 2kb 5′ and coding regions was amplified with the primer pair OMK574;OMK575, digested with PstI and NotI, and cloned into the pHS13 vector34, which contains 3/4pyroA53, a 3xFLAG tag, and the trpC terminator. The resulting plasmid pMK20 was then introduced into the recipient ∆nsdD strain TNJ108, and several TMK13 class transformants expressing the WT NsdD fused with the 3XFLAG tag under its native promoter have been isolated and confirmed.

Construction of A. flavus and A. fumigatus strains

The nsdD gene was deleted in A. flavus NRRL3357.5 (pyrG−)54 and A. fumigatus AFU293.1 (pyrG−)55 employing DJ-PCR51. In A. flavus strain, the 5′ and 3′ flanking regions of the nsdD gene were amplified using A. flavus WT (NRRL3357) genomic DNA with the primer pairs ONK1037;ONK1038 and ONK1039;ONK1040. The A. fumigatus pyrG+ marker was amplified from A. fumigatus WT (AFU293) genomic DNA with the primer pair OMK589;OMK590. The 5′ and 3′ flanking regions of nsdD were fused to the marker, and the resulting fusion product was further amplified by the nested primer pair ONK1041;ONK1042. The final deletion construct was introduced into A. flavus NRRL3357.5, and the ∆nsdD mutant (LNJ11) was isolated and confirmed by PCR followed by restriction enzyme digestion51.

In A. fumigatus strain, the 5′ and 3′ flanking regions of nsdD were amplified from A. fumigatus WT (AFU293) with the primer pairs ONK1043;ONK1044 and ONK1045;ONK1046. The A. nidulans pyrG+ marker was amplified from FGSC4 genomic DNA with the primer pair OHS696;OHS697. The 5′ and 3′ flanking regions of nsdD were fused to the marker, and the fusion product was further amplified by the nested primer pair ONK1047;ONK1048. The final deletion construct was introduced into A. fumigatus AFU293.1, and the ∆nsdD mutant (LNJ12) was isolated and confirmed by PCR followed by restriction enzyme digestion51. At least three independent deletion strains were isolated and confirmed.

Nucleic acid isolation and manipulation

Genomic DNA and total RNA isolation was carried out as previously described18,56. In Northern blot analyses, DNA probes were prepared by PCR amplification of the coding region of individual genes with appropriate oligonucleotide pairs using FGSC4 genomic DNA as template (Table S1). Probes were labelled with 32P-dCTP (PerkinElmer) using Random Primer DNA Labeling Kit (Takara) and purified by illustra MicroSpin G-25 columns (GE Healthcare).

Protein extraction and Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis of NsdD was performed using conidia, vegetative cells, and developing cells of TMK13. Individual samples including 2 d old conidia (2 × 108) were collected and resuspended in the lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH7.2], 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA), and homogenized by using a Mini Bead beater and 0.2 ml of silica-zirconium beads (Biospec)57. Protein concentration was colorimetrically determined using a Protein Assay System (BioRad). Approximately 10 μg of total proteins per a lane were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred onto immobilon-P membrane (Millipore). The membrane was incubated with the mouse monoclonal Anti-FLAG antibody (M2 clone, Sigma-Aldrich), and then subsequently incubated with a secondary antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase, HRP-Goat anti-mouse IgG (Millipore). The membrane was developed using enhanced chemilluminescence reagents (Amersham Biosciences).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay

Briefly, two days-old conidia (1 × 109 conidia) of TMK13 were crosslinked with fresh 1% formaldehyde for 30 min at RT. Then, 125 mM of glycine buffer was added to stop the cross-linking reaction. The conidia were resuspended in spore lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 15 mM EGTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1x protease inhibitor cocktail). Resuspended samples were mixed with silica beads and broken by a mini-bead beater for 3 min. Subsequently, the samples were sonicated for five cycles (30 s on, 60 s off) with a sonifier microtip at 70% amplitude and level 5 of output control57. The lysates were finally diluted in ChIP dilution buffer (0.01% SDS, 1.1% Triton X-100, 1.2 mM EDTA, 16.7 mM Tris/HCl, 167 mM NaCl, pH 8.0), and then the lysates were applied for ChIP assays according to the manufacturer’ instructions with a slight modification (MAGnify Chromatin Immunoprecipitaion System, Invitogen). The lysate was reacted with 1 μg of the mouse monoclonal Anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma-Aldrich). As a negative control, the chromatin extract was incubated with 1 μg of Anti-rabbit IgG in this assay. Individual input DNA samples before immune-precipitation (IP) were used as positive controls. Finally, the enriched DNA was purified and used as a template for PCR reactions with the GO Taq DNA polymerase (Promega). The primer sets used for PCR are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Gliotoxin analysis

Gliotoxin (GT) production was analyzed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) as described55. Briefly, spores (105/ml) of A. fumigatus strains were inoculated into 2 ml liquid MMG with 0.5% YE and stationary cultured at 37 °C up to 3 days. GT was extracted by CHCl3. Each sample was loaded onto a TLC silica plate including a fluorescence indicator (Kiesel gel 60, 0.25 mm; Merck). As a positive control, ~1 μg of GT standard (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was applied. The plate was then developed with toluene-ethyl acetate-formic acid (5:4:1, v/v/v) as mobile phase, where the R(f ) value of GT was ~0.61. Photographs of TLC plates were taken following exposure to UV (365 nm) using a Sony DSC-T70 digital camera. This analysis was performed in triplicates.

Microscopy

The colony photographs were taken by using a Sony digital camera (DSC-F28). Photomicrographs were taken using a Zeiss M2 Bio microscope equipped with AxioCam and AxioVision (Rel. 4.8) digital imaging software.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Lee, M.-K. et al. Negative regulation and developmental competence in Aspergillus. Sci. Rep. 6, 28874; doi: 10.1038/srep28874 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intelligent Synthetic Biology Center of Global Frontier Project (2011-0031955) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology grants, and a National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Korean Government (NRF-2011-619-E0002).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions M.-K.L. and N.-J.K. performed the experiments. M.-K.L., I.-S.L., S.J., S.-C.K. and J.-H.Y. designed the experiments and analyzed the data. M.-K.L. and J.-H.Y. wrote the main manuscript text. M.-K.L. prepared all Figures and Tables. All authors have reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Adams T. H., Wieser J. K. & Yu J.-H. Asexual sporulation in Aspergillus nidulans. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 62, 35–54 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni M., Gao N., Kwon N.-J., Shin K.-S. & Yu J.-H. Regulation of Aspergillus conidiation. In Cellular and Molecular Biology of Filamentous Fungi, Borkovich K. A. & Ebbole D. J. (eds). Washington, D.C., ASM Press 559–576 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod D. E., Gealt M. & Pastushok M. Gene control of developmental competence in Aspergillus nidulans. Dev Biol 34, 9–15 (1973). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yager L. N., Kurtz M. B. & Champe S. P. Temperature-shift analysis of conidial development in Aspergillus nidulans. Dev Biol 93, 92–103 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams T. H., Boylan M. T. & Timberlake W. E. brlA is necessary and sufficient to direct conidiophore development in Aspergillus nidulans. Cell 54, 353–62 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrianopoulos A. & Timberlake W. E. The Aspergillus nidulans abaA gene encodes a transcriptional activator that acts as a genetic switch to control development. Mol Cell Biol 14, 2503–15 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrianopoulos A. & Timberlake W. E. ATTS, a new and conserved DNA binding domain. Plant Cell 3, 747–8 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sewall T. C., Mims C. W. & Timberlake W. E. Conidium differentiation in Aspergillus nidulans wild-type and wet-white (wetA) mutant strains. Dev Biol 138, 499–508 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall M. A. & Timberlake W. E. Aspergillus nidulans wetA activates spore-specific gene expression. Mol Cell Biol 11, 55–62 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirabito P. M., Adams T. H. & Timberlake W. E. Interactions of three sequentially expressed genes control temporal and spatial specificity in Aspergillus development. Cell 57, 859–68 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H.-S. & Yu J.-H. Genetic control of asexual sporulation in filamentous fungi. Curr Opin Microbiol 15, 669–77 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etxebeste O., Garzia A., Espeso E. A. & Ugalde U. Aspergillus nidulans asexual development: making the most of cellular modules. Trends in Microbiology 18, 569–576 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etxebeste O. et al. Basic-zipper-type transcription factor FlbB controls asexual development in Aspergillus nidulans. Eukaryot Cell 7, 38–48 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oiartzabal-Arano E., Perez-de-Nanclares-Arregi E., Espeso E. A. & Etxebeste O. Apical control of conidiation in Aspergillus nidulans. Curr Genet 62, 371–7 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza C. A., Lee B. N. & Adams T. H. Characterization of the role of the FluG protein in asexual development of Aspergillus nidulans. Genetics 158, 1027–36 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon N.-J., Garzia A., Espeso E. A., Ugalde U. & Yu J.-H. FlbC is a putative nuclear C2H2 transcription factor regulating development in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol Microbiol 77, 1203–19 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garzia A., Etxebeste O., Herrero-Garcia E., Ugalde U. & Espeso E. A. The concerted action of bZip and cMyb transcription factors FlbB and FlbD induces brlA expression and asexual development in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol Microbiol 75, 1314–24 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo J.-A., Guan Y. & Yu J.-H. Suppressor mutations bypass the requirement of fluG for asexual sporulation and sterigmatocystin production in Aspergillus nidulans. Genetics 165, 1083–93 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni M. & Yu J.-H. A novel regulator couples sporogenesis and trehalose biogenesis in Aspergillus nidulans. PLoS One 2, e970 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo J.-A., Guan Y. & Yu J.-H. FluG-dependent asexual development in Aspergillus nidulans occurs via derepression. Genetics 172, 1535–44 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M.-K. et al. NsdD is a key repressor of asexual development in Aspergillus nidulans. Genetics 197, 159–73 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon N.-J., Shin K.-S. & Yu J.-H. Characterization of the developmental regulator FlbE in Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillus nidulans. Fungal Genet Biol 47, 981–93 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed Y. L. et al. The velvet family of fungal regulators contains a DNA-binding domain structurally similar to NF-kappaB. PLoS Biol 11, e1001750 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han K.-H. et al. The nsdD gene encodes a putative GATA-type transcription factor necessary for sexual development of Aspergillus nidulans. Mol Microbiol 41, 299–309 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao P., Shin K.-S., Wang T. & Yu J.-H. Aspergillus fumigatus flbB encodes two basic leucine zipper domain (bZIP) proteins required for proper asexual development and gliotoxin production. Eukaryot Cell 9, 1711–23 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cary J. W. et al. NsdC and NsdD affect Aspergillus flavus morphogenesis and aflatoxin production. Eukaryot Cell 11, 1104–11 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin K.-S., Kim Y.-H. & Yu J.-H. Proteomic analyses reveal the key roles of BrlA and AbaA in biogenesis of gliotoxin in Aspergillus fumigatus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 463, 428–33 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastushok M. & Axelrod D. E. Effect of glucose, ammonium and media maintenance on the time of conidiophore initiation by surface colonies of Aspergillus nidulans. J Gen Microbiol 94, 221–4 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timberlake W. E. Molecular genetics of Aspergillus development. Annu Rev Genet 24, 5–36 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urnov F. D. A feel for the template: zinc finger protein transcription factors and chromatin. Biochem Cell Biol 80, 321–33 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szewczyk E. & Krappmann S. Conserved regulators of mating are essential for Aspergillus fumigatus cleistothecium formation. Eukaryot Cell 9, 774–83 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf D. H. et al. Biosynthesis and function of gliotoxin in Aspergillus fumigatus. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 93, 467–72 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams T. H. & Timberlake W. E. Developmental repression of growth and gene expression in Aspergillus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87, 5405–9 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H.-S., Ni M., Jeong K.-C., Kim Y.-H. & Yu J.-H. The role, interaction and regulation of the velvet regulator VelB in Aspergillus nidulans. PLoS One 7, e45935 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrero-Garcia E. et al. Tip-to-nucleus migration dynamics of the asexual development regulator FlbB in vegetative cells. Mol Microbiol 98, 607–24 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H.-S. et al. Velvet-mediated repression of beta-glucan synthesis in Aspergillus nidulans spores. Sci Rep 5, 10199 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkahyyat F., Ni M., Kim S.-C. & Yu J.-H. The WOPR Domain Protein OsaA Orchestrates Development in Aspergillus nidulans. PLoS One 10, e0137554 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J.-H., Mah J.-H. & Seo J.-A. Growth and developmental control in the model and pathogenic aspergilli. Eukaryot Cell 5, 1577–84 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J.-H. Heterotrimeric G protein signaling and RGSs in Aspergillus nidulans. J Microbiol 44, 145–54 (2006). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krijgsheld P. et al. Development in Aspergillus. Stud Mycol 74, 1–29 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong Q. et al. Gbeta-like CpcB plays a crucial role for growth and development of Aspergillus nidulans and Aspergillus fumigatus. PLoS One 8, e70355 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo J.-A., Han K.-H. & Yu J.-H. Multiple roles of a heterotrimeric G-protein gamma-subunit in governing growth and development of Aspergillus nidulans. Genetics 171, 81–9 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang M.-H., Chae K.-S., Han D.-M. & Jahng K.-Y. The GanB Galpha-protein negatively regulates asexual sporulation and plays a positive role in conidial germination in Aspergillus nidulans. Genetics 167, 1305–15 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen S., Yu J.-H. & Adams T. H. The Aspergillus nidulans sfaD gene encodes a G protein beta subunit that is required for normal growth and repression of sporulation. EMBO J 18, 5592–600 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon N.-J., Park H.-S., Jung S., Kim S.-C. & Yu J.-H. The putative guanine nucleotide exchange factor RicA mediates upstream signaling for growth and development in Aspergillus. Eukaryot Cell 11, 1399–412 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H.-S. & Yu J.-H. Developmental regulators in Aspergillus fumigatus. J Microbiol 54, 223–31 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J.-H. Regulation of Development in Aspergillus nidulans and Aspergillus fumigatus. Mycobiology 38, 229–37 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontecorvo G., Roper J. A., Hemmons L. M., Macdonald K. D. & Bufton A. W. The genetics of Aspergillus nidulans. Adv Genet 5, 141–238 (1953). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo J.-A., Han K.-H. & Yu J.-H. The gprA and gprB genes encode putative G protein-coupled receptors required for self-fertilization in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol Microbiol 53, 1611–23 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kafer E. Meiotic and mitotic recombination in Aspergillus and its chromosomal aberrations. Adv Genet 19, 33–131 (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J.-H. et al. Double-joint PCR: a PCR-based molecular tool for gene manipulations in filamentous fungi. Fungal Genet Biol 41, 973–81 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szewczyk E. et al. Fusion PCR and gene targeting in Aspergillus nidulans. Nat Protoc 1, 3111–20 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osmani A. H., May G. S. & Osmani S. A. The extremely conserved pyroA gene of Aspergillus nidulans is required for pyridoxine synthesis and is required indirectly for resistance to photosensitizers. J Biol Chem 274, 23565–9 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z. M., Price M. S., Obrian G. R., Georgianna D. R. & Payne G. A. Improved protocols for functional analysis in the pathogenic fungus Aspergillus flavus. BMC Microbiol 7, 104 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue T., Nguyen C. K., Romans A., Kontoyiannis D. P. & May G. S. Isogenic auxotrophic mutant strains in the Aspergillus fumigatus genome reference strain AF293. Arch Microbiol 182, 346–53 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H.-S. & Yu J.-H. Multi-copy genetic screen in Aspergillus nidulans. Methods Mol Biol 944, 183–90 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong K.-C. & Yu J.-H. Investigation of in vivo protein interactions in Aspergillus spores., Methods Mol Biol 944, 251–257 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaaban M. I., Bok J. W., Lauer C. & Keller N. P. Suppressor mutagenesis identifies a velvet complex remediator of Aspergillus nidulans secondary metabolism. Eukaryot Cell 9, 1816–24 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookman J. L. & Denning D. W. Molecular genetics in Aspergillus fumigatus. Curr Opin Microbiol 3, 468–74 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.