A crowdsourced survey found that most Americans are aware that antibiotic misuse contributes to antibiotic resistance. The survey also found that Americans are less aware that antibiotic resistance is a significant problem and of the biologic mechanisms of bacterial resistance.

Keywords: antimicrobial resistance, crowdsourcing, public perception, qualitative research, survey

Abstract

Background. Little is known about the American public's perceptions or knowledge about antibiotic-resistant bacteria or antibiotic misuse. We hypothesized that although many people recognize antibiotic resistance as a problem, they may not understand the relationship between antibiotic consumption and selection of resistant bacteria.

Methods. We developed and tested a survey asking respondents about their perceptions and knowledge regarding appropriate antibiotic use. Respondents were recruited with the Amazon Mechanical Turk crowdsourcing platform. The survey, carefully designed to assess a crowd-sourced population, asked respondents to explain “antibiotic resistance” in their own words. Subsequent questions were multiple choice.

Results. Of 215 respondents, the vast majority agreed that inappropriate antibiotic use contributes to antibiotic resistance (92%), whereas a notable proportion (70%) responded neutrally or disagreed with the statement that antibiotic resistance is a problem. Over 40% of respondents indicated that antibiotics were the best choice to treat a fever or a runny nose and sore throat. Major themes from the free-text responses included that antibiotic resistance develops by bacteria, or by the infection, or the body (ie, an immune response). Minor themes included antibiotic overuse and antibiotic resistance caused by bacterial adaptation or an immune response.

Conclusions. Our findings indicate that the public is aware that antibiotic misuse contributes to antibiotic resistance, but many do not consider it to be an important problem. The free-text responses suggest specific educational targets, including the difference between an immune response and bacterial adaptation, to increase awareness and understanding of antibiotic resistance.

In the United States, multidrug-resistant pathogens and Clostridium difficile cause over 2 500 000 infections each year [1, 2]. Infections caused by antibiotic-resistant pathogens increase the cost of medical care ($6000–$30 000 per patient) [3], resulting in an estimated economic burden of $20 billion per year [3, 4]. Both the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and World Health Organization (WHO) recognize antibiotic resistance as a global health threat [1, 5]. The reasons for widespread antibiotic resistance are multifactorial and include providers' practice patterns as well as the public's perceptions about, and sometimes demands for, antibiotics [6].

To help slow the development of antibiotic resistance, several nations have developed public health campaigns that promote prudent use of antibiotics, focusing their efforts on avoiding antibiotics to treat cold symptoms, particularly for children. In 2003, the CDC launched its national Get Smart: Know When Antibiotics Work campaign. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control followed in 2008, publicizing an annual European Antibiotic Awareness Day. Most recently, the WHO announced the first World Antibiotic Awareness Week in 2015. These campaigns encourage the public to ask for fewer antibiotics, although their overall effectiveness appears modest at best [7–9].

An investigation from 1999 about the views of the American public towards antibiotics suggested important knowledge gaps regarding appropriate use and potential dangers [10]. Subsequent studies demonstrate that although a significant proportion of the American public still believes that antibiotics are effective treatment for cold symptoms, they also report increasing awareness of antibiotic resistance [11, 12]. We hypothesized that although the American public may now perceive antibiotic resistance as a danger, they do not recognize that antibiotic misuse or overuse contributes to the selection for antibiotic-resistant bacteria. To test our hypothesis, we surveyed a proxy of the US population, recruiting respondents through the online crowdsourcing platform Amazon Mechanical Turk. The survey specifically queried respondents' knowledge and beliefs concerning antibiotics and antibiotic resistance as well as their definition of the term “antibiotic resistance.”

METHODS

Ethics Statement

The study protocol and survey was reviewed and exempted by the Institutional Review Board at the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine.

Survey Instrument

We developed a survey to assess the perceptions and knowledge of nonmedical personnel about antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance. We adapted 5 multiple-choice items from a previously validated survey conducted in Britain [13]. A focus group of 20 nonmedical personnel pretested the survey prior to pilot testing. The final 13-item survey began by collecting demographic data. To prevent introduction of within-survey bias, the first survey question after the demographics section asked respondents to use their own words to define antibiotic resistance. The answer field permitted up to 500 characters of free text. Next, questions written on a 5-point Likert scale assessed perceptions and knowledge of antibiotic use and resistance. Two questions asked respondents to select, from among 9 options, the 5 most common situations that would most likely cause infection and the 5 most common means of infection transmission. Finally, a 2-part question asked respondents to indicate whether they had previously heard of terms “MRSA” (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus), “Superbug,” and “C-Diff” (C difficile) to describe antibiotic resistance and the associated source of information. The survey was anonymous, voluntary, administered via an internet link (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) and took approximately 20 minutes to complete.

The survey was pilot tested before final dissemination, as detailed below. Several analytic tests assessed the construct validity of the survey questions from the crowdsourced population. These included identification of the floor and ceiling effects of each item, analysis of the distribution of responses, and analysis of response/no response patterns to questions. In addition, exploratory factor analysis using principal components analysis with varimax rotation identified consistent factor structure, as described elsewhere [8].

Study Respondents and Recruitment

Respondents were recruited through Mechanical Turk ([MTurk] Amazon, Seattle, WA), an online web-based platform for recruiting and paying subjects to perform tasks. The advantages of MTurk include recruiting respondents from a wide range of ages and socioeconomic status as well as diverse ethnicities [14]. Previous researchers have verified that MTurk demographic responses are accurate, with valid and replicable psychometric properties [14–16]. Eligibility criteria included respondents who were English-speaking, had an address within the United States, and were ≥18 years. Upon completion of the survey, respondents received a unique code generated by Qualtrics. The respondents submitted this code to MTurk to receive $0.30 in compensation. The unique code also served to prevent respondents in the final sample from taking the survey more than once.

The survey was pilot tested on a small sample (n = 49) to assess the interaction between MTurk and Qualtrics and to perform initial tests of construct validity. The respondents' internet protocol (IP) address, indexed within Qualtrics, was correlated with their MTurk work identification number. Demographics and responses from the pilot sample informed calculations for the sample size recruited for the final survey [17].

To ensure representativeness of the respondents included in the final sample, the individual surveys were released in batches of 15 for a total of 225 surveys. The timing of the batches was released in recognition of different employment types and rates of unemployment within the North, South, East, and West regions of the United States, as defined by the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Library of Congress [18]. Therefore, a batch of surveys would be released according to typical work shifts according to the time zone for each region: first (8:00 am to 5:00 pm), second (4:00 pm to midnight), or third shift (11:00 pm to 8:00 am). This allowed for a broader variation of participants in the study in the areas of age, education, income, and race.

Data Analysis

Quantitative data were summarized using descriptive statistics. For questions that used a 5-point Likert scale, outcomes were collapsed to 3 variables: agree, disagree, or neutral. Demographic characteristics were compared with the American public with either a non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank, proportional test or Kruskall-Wallis, as adequate. A P value of <.05 was considered significant. All statistical analytics were conducted using R (version 3.1.3; Vienna, Austria) [19].

We used a thematic framework analysis specifically designed for applied qualitative research to identify emergent themes from respondents' antibiotic resistance definitions entered as free-text [20]. This approach combines qualitative and quantitative methodology. The qualitative approach started deductively from preset research objectives that also allowed new themes to emerge from the data. The first 2 stages are familiarization and identifying a thematic framework. The third stage, indexing, complements the qualitative work using quantitative analysis, detailed below. The fourth stage, charting, involved retrieving the coded data, producing summaries of each theme for individual respondents and visually arranging it in a table to build an overall picture of the whole data set. In the fifth stage, mapping, the tables are used to map and interpret the data set as a whole and connect with the original research objectives. To complete the qualitative analysis, free-text responses were coded independently by 2 raters (R. R. C. and R. L. P. J.) until interrater agreement was reached; discrepancies were discussed, and the framework was revised until there was a shared understanding of theme definitions.

Two quantitative methods, used in parallel, supported indexing the themes from the free-text responses (Stage 3 above). The first method used natural language processing (NVivo version 10 qualitative software; QSR International Pty Ltd, Burlington, MA) to categorize free-text responses into overall themes and subthemes. The second quantitative method used text mining to characterize the free-text responses based on word frequency, relationships between words, and Euclidian distance between words within phrases [21, 22]. The approach utilized text preprocessing such as stopword removal and the Porter suffix-stripping algorithm for dimensionality reduction [23]. Subsequently, text mining software summarized the responses by word frequencies, independent of grammar and word order [21]. Finally, a network diagram permitted visualization of the relationships, and strength of those relationships, among 50 most frequently used words [22].

RESULTS

Of 225 respondents, 215 (96%) completed the full survey; among these, the median age was 37 years (range, 18–73 years) (Table 1). Compared with the distributions described by the US 2010 Census (median age, 37.2 years) [24], our respondents appeared slightly biased towards a younger age (P = .048 for a one-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test). As is typical of crowdsourced populations, our respondents reported on average a higher level of education compared with the US public with 47% vs 30%, respectively, having obtained an undergraduate degree or higher (P < .001 with the proportional test) [24]. The distribution of respondents' gender and race did not differ significantly from the distributions described by the US 2010 Census using a Kruskal-Wallis test.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Respondents Recruited From Amazon Mechanical Turk

| Characteristics | Respondents N = 215 (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 93 (43) |

| Female | 122 (57) |

| Age (years)a | |

| 18–29 | 69 (32) |

| 30–39 | 75 (35) |

| 40–49 | 31 (14) |

| 50–64 | 34 (16) |

| >65 | 4 (2) |

| Raceb | |

| White | 166 (76) |

| Black | 13 (6) |

| Asian | 19 (9) |

| Otherc | 16 (9) |

| Level of education | |

| Did not complete high school | 3 (1) |

| Completed high school | 112 (52) |

| Completed an undergraduate degree or higher | 100 (47) |

| Annual income | |

| >$25 000 | 61 (28) |

| $25 000–$49 999 | 57 (26) |

| $50 000–$74 999 | 53 (25) |

| $75 000–$100 000 | 27 (13) |

| >$100 000 | 17 (8) |

a Two did not report age.

b One did not report race.

c Includes Multiracial, Hispanic, and Pacific Islander.

When queried about their perceptions of antibiotic use, the majority of respondents agreed that inappropriate antibiotic use contributes to antibiotic resistance (187; 93%) and that using fewer antibiotics will decrease antibiotic resistance (138; 69%) (Table 2). Interestingly, although they agreed that resistance to antibiotics is a problem in American hospitals (155; 76%), a similar proportion (70%) responded neutrally or disagreed with the statement that antibiotic resistance is a problem. Finally, most respondents (180; 89%) agreed that people can build immunity to antibiotics.

Table 2.

Respondent's Knowledge and Beliefs Regarding Antibiotic Use and Antibiotic Resistance

| Perceptions and Knowledge | Strongly Agree/Agree | Neutral | Strongly Disagree/Disagree | Missing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Antibiotic Resistance | ||||

| The inappropriate use of antibiotics could lead to development of resistant bacteria. | 187 (93) | 13 (6) | 3 (1) | 12 |

| Resistance to antibiotics is a problem in US hospitals. | 155 (76) | 44 (22) | 2 (2) | 14 |

| Antibiotic-resistant bacteria could infect me or my family. | 147 (74) | 35 (18) | 18 (8) | 15 |

| Antibiotic resistance is a significant problem. | 61 (30) | 94 (47) | 45 (23) | 15 |

| There is no connection between taking antibiotics and the development of resistant bacteria. | 12 (6) | 25 (12) | 164 (82) | 14 |

| Preservation of Antibiotic Efficacy | ||||

| If taken too often, antibiotics are less likely to work in the future. | 182 (90) | 10 (5) | 10 (5) | 13 |

| We will lose the ability to use antibiotics in the future if preventative measures are not taken. | 146 (73) | 38 (19) | 17 (8) | 14 |

| Using fewer antibiotics will decrease antibiotic resistance. | 138 (69) | 41 (20) | 22 (11) | 14 |

| The use of antibiotics for livestock leads to resistant bacteria in meat that can make people sick. | 122 (60) | 63 (31) | 18 (9) | 12 |

| Limitations on antibiotics will cause more harm than good. | 38 (19) | 58 (28) | 107 (53) | 12 |

| Prescribers | ||||

| I trust my doctor's/nurse's advice as to whether I need antibiotics or not. | 148 (72) | 40 (20) | 17 (8) | 10 |

| Antibiotics are overprescribed by doctors and nurses. | 142 (71) | 40 (20) | 18 (9) | 15 |

| Doctors and nurses are adequately educated regarding antibiotic resistance. | 113 (55) | 48 (23) | 44 (22) | 10 |

| Personal Use | ||||

| A course of antibiotics can make a person feel better. | 170 (83) | 28 (14) | 7 (3) | 10 |

| You should take all the antibiotics you are prescribed. | 168 (82) | 18 (9) | 19 (9) | 10 |

| It does not matter what time of day an antibiotic is taken. | 45 (22) | 48 (24) | 112 (55) | 10 |

| It is OK to keep unused antibiotics and use them later without advice from a doctor or nurse. | 17 (8) | 19 (9) | 168 (83) | 11 |

| Knowledge of Antibiotics | ||||

| Antibiotics can kill bacteria. | 182 (90) | 12 (6) | 9 (4) | 12 |

| It is possible that I could build an immunity to certain antibiotics over time. | 180 (89) | 13 (6) | 9 (4) | 13 |

| Antibiotics can kill bacteria that normally live on the skin and in the gut. | 160 (81) | 22 (11) | 18 (8) | 15 |

| Antibiotics can kill viruses. | 60 (29) | 12 (6) | 131 (65) | 12 |

| Antibiotics work on most coughs and colds. | 49 (24) | 24 (12) | 130 (64) | 12 |

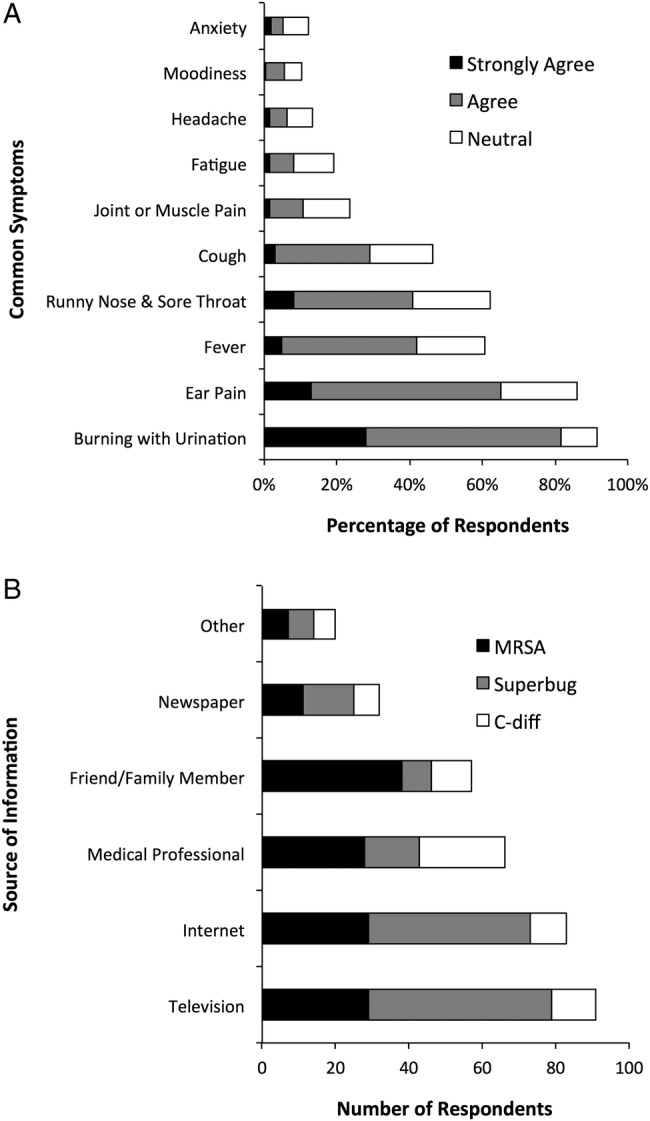

Figure 1A shows the proportion of respondents who agreed that antibiotics are the best choice to treat several common symptoms. Fewer than 10% of respondents believed that antibiotics are the best choice to treat fatigue, headache, moodiness, or anxiety. Figure 1B shows the number of respondents who have heard the terms MRSA, “Superbug”, or “C-diff” used by the lay press in association with antibiotic resistance. Medical professionals were the third most common source of information and the most frequent source among those who had heard of “C-diff”. When asked about situations most likely to cause infections, respondents selected the following: lack of hand washing (190, 88%), poor hospital hygiene (165, 77%), touching door knobs and other common objects (eg, money; 140, 65%), close contact with children (132, 61%), and being out in public (107, 50%).

Figure 1.

(A) Percentage of respondents who agree/strongly agree that antibiotics are the best choice to treat several common symptoms. For each symptom listed on the y-axis, at least 199 respondents recorded a response on a 5-point Likert scale. (B) Number of respondents indicating previous awareness of terms commonly used to describe antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Respondents who indicated familiarity with the terms MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) (N = 142; 66%), “Superbug” (N = 138, 64%), or “C-diff” (Clostridium difficile) (N = 69; 32%) were asked to select the source of their information from the options listed on the y-axis. No additional information was requested from respondents who selected “Other” as their source of information.

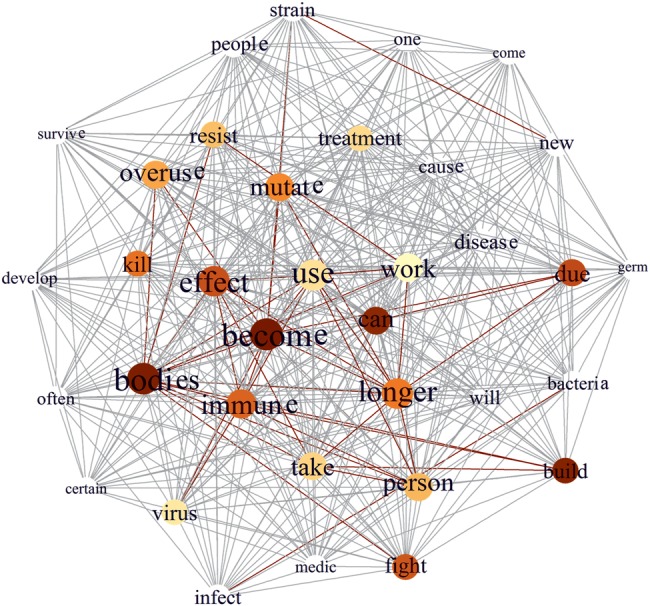

The survey included a free-text question where respondents described antibiotic resistance in their own words. From 198 valid responses, several themes emerged. To support identification of these themes, we examined the relationships among terms used by respondents to define antibiotic resistance (Figure 2). In this visualization, label and node sizes indicate the strength of those relationships among words. The words “bodies”, “become”, “immune”, and “effect” had the highest probability of connecting across the entire network of terms. The words “bodies” and “immunity” exhibited among the highest degree of correlation to each other.

Figure 2.

The diagram shows relationships among terms used by respondents to define antibiotic resistance and supported identification of emerging themes. White nodes and gray lines indicate a degree of correlation equal to or below the 75th quartile. Colored nodes and lines indicate a degree of correlation exceeding the 75th quartile. For the nodes, larger size and darker color reflect increasing correlation with the most frequently used term “become”. Multiple permutations of the same word were grouped together (eg, “immun” represents both “immunity” and “immune”). For clarity, the figure shows a single word to represent those permutations.

Through framework analysis we distinguished 3 major themes based upon the entity that develops resistance to antibiotics (Table 3). These were bacteria (78; 40%, P < .001), the body (72; 36%, P < .001), and the infection or illness (20; 10%, P = .90). A subset of responses did not contain any of the major themes (28; 14%). Minor themes, cataloged as subsets of the major themes, conveyed reasons for or causes of antibiotic resistance. The first minor theme addressed antibiotic overexposure, overprescription, overuse and misuse, often conjointly with idea that failure to complete antibiotic courses promotes antibiotic resistance. The second minor theme, about evolution, mutation, and adaptation, appeared primarily among the responses correctly relating antibiotic resistance to bacteria. A third minor theme indicated that an immune response, developed by bacteria, the body, or the illness, resists antibiotics. This was the most common minor theme among responses within the major theme that one's physical body is what becomes resistant to antibiotics. Finally, 2 responses indicated that an allergic reaction (minor theme) generated by the body (major theme) caused antibiotic resistance. A small proportion of respondents (20; 10%) equated viruses with bacteria.

Table 3.

Thematic Framework of Respondents' Understanding of Antibiotic Resistance

| Major Themesa | Minor Themesb | No. (%)c N = 198 | Representative Responsesd |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria become resistante | 78 (40) | When microbes become resistant to the effects of antibiotics. | |

| Evolution, adaptation, or mutation | 32 | A bacteria that has mutated in a way that makes a certain antibiotic ineffective. | |

| Overuse, overexposure, or misuse | 23 | Antibiotic resistance in medicine comes from microbes developing a resistance from antibiotics that are prescribed unnecessarily or when patients do no complete dosages. | |

| Immune response | 8 | When somebody has an infection in their body, but antibiotics will not help the person get better. The bacteria or virus has become immune to the antibiotics. | |

| The body becomes resistant | 72 (36) | Antibiotic resistance is when your body actually fights off antibiotics, which are put in to help kill viruses. The body can even take focus off of the virus and go strictly after the antibiotic. | |

| Evolution, adaptation, or mutation | 1 | People are becoming resist to antibiotics, and some diseases have even mutated (a new strain of antibiotic- resistant Gonorrhea was recently in the news), due to overuse and misuse of antibiotics. | |

| Overuse, overexposure, or misuse | 17 | When a person has been on too many prescriptions of antibiotics, your body gets used to it and the antibiotics no longer work. | |

| Immune response | 19 | Antibiotic resistance is when your body becomes immune to antibiotics and they no longer work as effectively. | |

| Allergy | 2 | Antibiotics are medicine to combat illness, and resistance means there is an allergy or physical reason why the antibiotic is not working. | |

| The infection or illness becomes resistant | 20 (10) | It means a disease is not affected by antibiotics. | |

| Evolution, adaptation, or mutation | 2 | It is when diseases mutate in response to antibiotics and cannot be treated with them. | |

| Overuse, overexposure, or misuse | 5 | When an illness is able to resist treatment with antibiotics because it has been exposed too many times to the antibiotic. | |

| Immune response | 2 | Antibiotic resistance is when a disease builds immunity to an antibiotic. | |

| No specific source identified | 28 (14) | When antibiotics are ineffective. | |

| Overuse, overexposure, or misuse | 8 | When an antibiotic is overused and becomes ineffective as a result. | |

a Major themes addressed the entity that develops resistance. A single major theme was selected for each response. Not all responses indicated the source or entity responsible for antibiotic resistance.

b Minor themes addressed the reasons for or causes of antibiotic resistance. Some responses had more than 1 minor theme.

c Of 215 respondents, 198 offered valid responses to this question. Invalid answers included “xxxx”, “1234”, and similar responses.

d All responses are verbatim.

e Twenty of 198 responses mentioned viruses, using the term as interchangeable with bacteria.

DISCUSSION

Our survey of a proxy of the American public found that over 90% of participants recognize that inappropriate antibiotic use fosters the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Approximately 75% of our respondents also agreed that that resistance to antibiotics is a problem in US hospitals and that resistant bacteria could infect them or a family member. These findings are similar to those reported in a similar survey of the British public [8]. However, only 30% of our respondents agreed that antibiotic resistance is a significant problem. This may indicate that respondents consider other problems as more important or, as reported for the British public, that they do not perceive they have a personal role or power to influence antibiotic resistance [25].

Furthermore, our survey found that approximately 90% of participants agreed that they could build immunity to antibiotics over time. Thematic analysis of participants' free-text definition of antibiotic resistance revealed that over one third of our respondents perceive antibiotic resistance to be a function of the human body, rather than bacteria. Figure 2 highlights the strong interconnectedness between the idea of “body” and “immune” expressed in the free-text responses. Only demographic items preceded the free-text question, which indicates that the theme of relating antibiotic resistance to the body becoming immune is extant among a sizeable portion of our respondents. The misconception that humans become resistant to antibiotics is not unique to Americans. A study from Sweden found that over 85% of their respondents also held this belief [26]. In addition, the WHO recently conducted a survey across 12 nations as part of their global initiative to change the way antibiotics are used. They found a similar proportion of respondents (76%) agree that the body becomes resistant to antibiotics [5]. In a study that included participants from 9 European countries, Brookes-Howell et al [27] conducted a qualitative study about antibiotic resistance and also detected a strong theme of resistance as a property of the body. In face-to-face interviews, they found that participants interpreted resistance to mean that an antibiotic did not work, and respondents perceived this problem could be overcome with a stronger antibiotic.

Other knowledge gaps found among respondents to our survey reflect those found in other nations. Approximately 30% of respondents from our survey and approximately 40% from a 2003 British study agreed that antibiotics can kill viruses [13]. The same study also found that approximately 40% of respondents agreed that antibiotics work on most coughs and colds [13]. Although less than 25% of participants in our survey agreed that antibiotics work on most coughs and colds, approximately 40% agreed that antibiotics were the best choice to treat cold symptoms, ie, a runny nose and sore throat. Among those surveyed by the WHO, approximately two thirds of respondents believe that antibiotics would treat a sore throat (70%) and colds and flu (64%) [7]. These findings suggest that educational materials about appropriate antibiotic use may have utility in several countries. Two studies of US adult consumers, conducted 12 years apart, show some positive shifts with regard to knowledge about antibiotic use [28, 29]. In 1998–1999, 27% of respondents agreed that when they have a cold, they should take antibiotics to prevent getting a more serious illness, compared with 17% in 2012–2013.

Participants in our study identified television and the internet as the most common source of information about antibiotic-resistant bacteria. This contrasts with the WHO survey, in which respondents reported a doctor or nurse as their source for learning about antibiotic-resistant bacteria [7]. This difference may reflect differences in access to media between Americans and people living in nations included in the WHO survey. Notably, participants from our survey agreed that doctors or nurses overprescribe antibiotics (71%) and may not have sufficient education about antibiotic resistance (55%). Yet, the majority of participants in our survey also indicated that they trusted their doctor's or nurse's advice about whether or not antibiotics were needed (72%). This apparent contradiction suggests that respondents may have more faith in their own doctor and nurse, compared with providers in general. A Swedish survey reported most participants indicated trust in providers prescribing (81%) or not prescribing (87%) an antibiotic [26]. As suggested by André et al [26], these results indicate that providers themselves may be a powerful resource of improving antibiotic use.

Our study has some limitations. First, we used a relatively small sample size (n = 215) to enable a detailed thematic analysis of the results from the free-text question. The number of participants did not permit accurate subgroup analysis based on education, income, nor race. Second, we included several novel questions. To test their construct validity, we applied the same analysis to both our novel questions and to questions adapted from previously validated surveys [8]. Outcomes from the analytic tests yielded consistent responses from all of the multiple-choice questions, indicating generalizability of the survey for a crowdsourced population. Third, crowdsourcing is a relatively recent approach for surveying the public about healthcare-related matters [15, 30]. American MTurk workers have been evaluated thoroughly in the literature and are arguably closer to the US population as a whole than subjects recruited from traditional university subject pools [14]. Furthermore, conducting experimental research on MTurk offers benefits such as a low risk of dishonest responses, no risk of experimenter effects, and low susceptibility to coverage error in comparison to traditional studies [16]. The similarity between our results and those of previous surveys around the general topic of antibiotic resistance suggest that it would be reasonable for future studies to use our approach.

CONCLUSIONS

Our results highlight the continued need for education to the American public about the biological events that lead to antibiotic resistance. Specific knowledge gaps are that antibiotics are effective against bacteria, not viruses, and that antibiotic resistance is a property developed by bacteria, not people. Given that most of our participants indicated that they trust their doctor or nurse, these professionals may be the most effective at teaching patients about prudent antimicrobial use.

Acknowledgments

R. L. P. J. gratefully acknowledges the T. Franklin Williams Scholarship with funding provided by Atlantic Philanthropies, Inc.; the John A. Hartford Foundation, the Association of Specialty Professors, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, and the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases.

Disclaimer. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Financial support. Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the NIH, through the Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland (grant UL1TR000439) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) component of the NIH and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research (to R. L. P. J.). This study was also supported in part by funds and/or facilities provided by the Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs and the Veterans Integrated Service Network-10 Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (to R. L. P. J.).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antimicrobial Resistance Threats in the United States, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013/index.html Accessed 21 October 2013.

- 2.Kelly CP, LaMont JT. Clostridium difficile—more difficult than ever. N Engl J Med 2008; 359:1932–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maragakis LL, Perencevich EN, Cosgrove SE. Clinical and economic burden of antimicrobial resistance. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2008; 6:751–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts RR, Hota B, Ahmad I et al. Hospital and societal costs of antimicrobial-resistant infections in a Chicago teaching hospital: implications for antibiotic stewardship. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 49:1175–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance 2014. Available at: http://www.who.int/drugresistance/documents/surveillancereport/en/ Accessed 9 October 2015.

- 6.Michael CA, Dominey-Howes D, Labbate M. The antimicrobial resistance crisis: causes, consequences, and management. Front Public Health 2014; 2:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Antibiotic resistance: Multi-country public awareness survey. Available at: http://www.who.int/drugresistance/documents/baselinesurveynov2015/en/ Accessed 4 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.McNulty CA, Nichols T, Boyle PJ et al. The English antibiotic awareness campaigns: did they change the public's knowledge of and attitudes to antibiotic use? J Antimicrob Chemother 2010; 65:1526–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gualano MR, Gili R, Scaioli G et al. General population's knowledge and attitudes about antibiotics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2015; 24:2–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vanden Eng J, Marcus R, Hadler JL et al. Consumer attitudes and use of antibiotics. Emerg Infect Dis 2003; 9:1128–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonzales R, Corbett KK, Leeman-Castillo BA et al. The ‘minimizing antibiotic resistance in Colorado’ project: impact of patient education in improving antibiotic use in private office practices. Health Serv Res 2005; 40:101–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watkins LK, Sanchez GV, Albert AP et al. Knowledge and attitudes regarding antibiotic use among adult consumers, adult Hispanic consumers, and health care providers—United States, 2012–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015; 64:767–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McNulty CA, Boyle P, Nichols T et al. Don't wear me out—the public's knowledge of and attitudes to antibiotic use. J Antimicrob Chemother 2007; 59:727–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mason W, Suri S. Conducting behavioral research on Amazon's Mechanical Turk. Behav Res Methods 2012; 44:1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carter RR, DiFeo A, Bogie K et al. Crowdsourcing awareness: exploration of the ovarian cancer knowledge gap through Amazon Mechanical Turk. PLoS One 2014; 9:e85508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paolacci G, Chandler J, Ipeirotis PG. Running experiments on Amazon Mechanical Turk. Judgment and Decision Making 2010; 5:411–9. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma J, Sun J, Sedransk J. Modern sample size determination for unordered categorical data. Stat Interface 2014; 7:219–33. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bureau of Labor Statistics. Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey. Available at: http://www.bls.gov/cps/ Accessed 11 February 2016.

- 19.R: The R Project for Statistical Computing. Available at: https://www.r-project.org/ Accessed 10 October 2015.

- 20.Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: The Qualitative Researcher's Companion. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002: pp 305–29. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meyer D, Hornik K, Feinerer I. Text mining infrastructure in R. J Stat Softw 2008; 25:1–54. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Csardi G, Nepusz T. The igraph software package for complex network research. Inter J Complex Syst 2006; 1695:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Porter MF. An algorithm for suffix stripping. Program 1980; 14:130–7. [Google Scholar]

- 24.United States Census 2010. 2010 Census Data. Available at: http://www.census.gov/2010census/data/ Accessed 11 February 2016.

- 25.Hawkings NJ, Wood F, Butler CC. Public attitudes towards bacterial resistance: a qualitative study. J Antimicrob Chemother 2007; 59:1155–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.André M, Vernby A, Berg J, Lundborg CS. A survey of public knowledge and awareness related to antibiotic use and resistance in Sweden. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010; 65:1292–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brookes-Howell L, Elwyn G, Hood K et al. ‘The body gets used to them’: patients' interpretations of antibiotic resistance and the implications for containment strategies. J Gen Intern Med 2012; 27:766–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vanden Eng J, Marcus R, Hadler JL et al. Consumer attitudes and use of antibiotics. Emerging Infect Dis 2003; 9:1128–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Francois Watkins LK, Sanchez GV, Albert AP et al. Knowledge and attitudes regarding antibiotic use among adult consumers, adult Hispanic consumers, and health care providers--United States, 2012–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015; 64:767–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brady CJ, Villanti AC, Pearson JL et al. Rapid grading of fundus photographs for diabetic retinopathy using crowdsourcing. J Med Internet Res 2014; 16:e233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]