Abstract

Introduction:

Community pharmacists are in a suitable position to give advice and provide appropriate services related to sleep disorders to individuals who are unable to easily access sleep clinics. An intervention with proper objective measure can be used by the pharmacist to assist in consultation.

Objectives:

The study objectives are to evaluate: (1) The effectiveness of a community pharmacy-based intervention in managing sleep disorders and (2) the role of actigraph as an objective measure to monitor and follow-up individuals with sleeping disorders.

Methods and Instruments:

The intervention care group (ICG) completed questionnaires to assess sleep scale scores (Epworth Sleepiness Scale [ESS] and Insomnia Severity Index [ISI]), wore a wrist actigraph, and completed a sleep diary. Sleep parameters (sleep efficiency in percentage [SE%], total sleep time, sleep onset latency, and number of nocturnal awakenings) from actigraphy sleep report were used for consultation and to validate sleep diary. The usual care group (UCG) completed similar questionnaires but received standard care.

Results:

Pre- and post-mean scores for sleep scales and sleep parameters were compared between and within groups. A significant difference was observed when comparing pre- and post-mean scores for ISI in the ICG, but not for ESS. For SE%, an increase was found in the number of subjects rated as “good sleepers” at post-assessment in the ICG.

Conclusions:

ISI scores offer insights into the development of a community pharmacy-based intervention for sleeping disorders, particularly in those with symptoms of insomnia. It also demonstrates that actigraph could provide objective sleep/wake data to assist community pharmacists during the consultation.

KEY WORDS: Actigraph, community pharmacy, intervention, pharmacist, sleeping disorders

Worldwide, prevalence rates of sleep disorders are high and increasingly encountered in primary healthcare settings. In Australia, the prevalence rate of sleep disorders in the general population are considered to be high, and are estimated to affect about 1.5 million or 8.9% of the population;[1] the most common are obstructive sleep apnea (4%),[2,3] chronic insomnia (5%),[4] and periodic limb movement disorder (3.9%).[5] Sleep disorders are known to be associated with diseases and problems such as diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, impaired cognitive function, poor school or work performance, and memory disturbance.[6,7,8]

New interventions are needed to provide more accessible primary care options to assist those with/or at risk of sleep disorders, as alternatives to sleep specialists who often have longer waiting times, and can be expensive if additional procedures are required. In fact, it was found that treatment under a primary healthcare model, compared with a specialist model, resulted in similar patient outcomes.[9] Community pharmacists can offer primary assistance to help individuals with sleeping disorders because they are usually more accessible, and also highly trained in therapeutics, medicines, diseases state management, health education, and face-to-face counseling.[10] This, therefore, places them in an ideal position to play a role in the management of sleep-related disorders, by initiating conversation, discussing medicines, and providing continuous assessments. Monitoring and following up individuals with sleeping disorders can be difficult without appropriate instruments or standard intervening measures. While most previous research on community pharmacy-based interventions for sleep disorders focused on developing screening tools, [11,12,13,14] there is an opportunity to develop an intervention that monitors and follows-up the patients, particularly after treatment was sought.

Using a step-wise approached, this feasibility study was conducted to tackle “poor sleep” in walk-in individuals who attended the community pharmacy seeking help for the condition. An intervening model of care inclusive of baseline assessment, monitoring, and follow-up to gain feedback on sleep, was developed. For this purpose, a wrist-watch device, actigraph, was utilized. Being convenient and portable, actigraph is a practical device for use in the community and home-based environment.[15,16,17] While assessing sleep/wake patterns is difficult when self-reporting is poor or subjective measuring tools are used, actigraph can overcome this challenge by providing objective and graphical data, and by measuring gross motor activities to infer sleep/wake patterns.[18] Actigraph can identify certain sleep parameters and can also be used to validate self-reported feedback whenever self-report and actigraphy data are used concurrently.[19]

This paper describes an intervention developed to assist the pharmacist in improving the management of sleep disorders at the community pharmacy. The study objectives are to evaluate the effectiveness of a community pharmacy-based intervention in managing sleep disorders and to evaluate the role of actigraph as an objective measure to monitor and follow-up individuals who attended community pharmacy seeking assistance for sleeping disorders.

Ethical approval

This project was approved by the School of Pharmacy Ethics Committee, University of Queensland. This study also has been registered with the Australia New Zealand Clinical Trial Registry (ANZCTR1261200082585) for conducting research using human subjects.

Methods and Instruments

A complete study protocol has been published in BMC Health Services Research.[20]

Study design and setting

This study was a community-based intervention, prospective controlled trial, with one intervention group and one control group, and involved three community pharmacies in Brisbane area with similar demographic criteria and physical locations.

Study population

Participants

Participants were recruited among community pharmacy customers who attended the participating pharmacies seeking assistance for sleeping disorders and “poor sleep.” Eligible participants were walk-in customers, aged 18 years and above, could read, wrote, and spoke adequate English to complete the questionnaire and consultation sessions, not pregnant, not currently under treatment with continuous positive airway pressure and agreed to give consent.[20]

Community pharmacies

Community pharmacies were contacted from publically available lists. Pharmacies which met the study criteria[20] were contacted through telephone and informed about the project, and were invited to participate. If the pharmacist expressed an interest, a research officer arranged a face-to-face meeting to further discuss the study and obtained consent. Pharmacies were later assigned to either the intervention care group (ICG) or usual care group (UCG). Upon consent, the ICG pharmacists and pharmacy staff received a brief session (about 20–30 min) in the pharmacy about the actigraph, the sleep diary, the questionnaires, and the forms related to the study, and were provided the actigraph user's manual. A researcher also assisted with the installation of proprietary software to a computer in the pharmacy, which enabled data to be downloaded from the actigraph to generate graphical sleep/wake data, as in Figures 1 and 2[22] for each participant. The ICG pharmacy also had a private counseling area within the premise and agreed to follow-up the participants for 2 weeks from baseline.

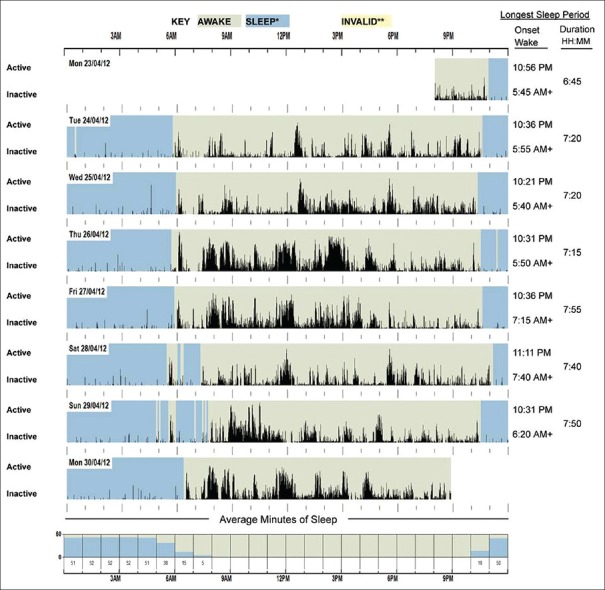

Figure 1.

Example of a graphical sleep/wake data plot from a normal sleeper downloaded from the actigraph using the proprietary software. Sleep onset time, wake after sleep onset, and duration of sleep (total sleep time per day) can be obtained from this plot

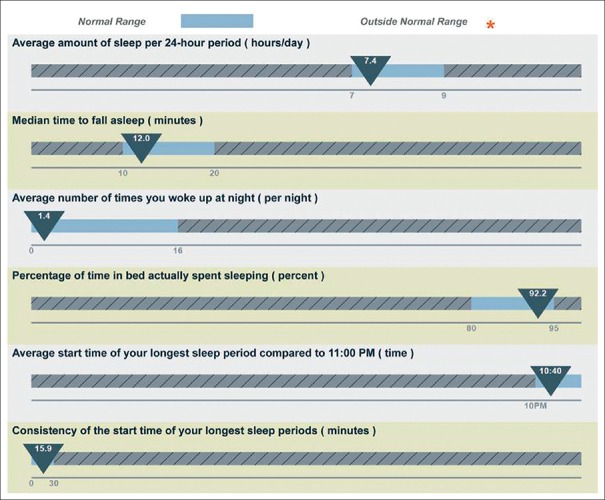

Figure 2.

Example of sleep statistics downloaded from actigraphy data for a normal sleeper (Average amount of sleep per 24-hour period (hours/day) = average of total sleep time (TST) per 24-hour period (hours/day). Median time to fall asleep = median of sleep onset latency (SOL), minutes. Average number of times you woke up at night = number of nocturnal awakenings (NWAK), times. Percentage of time in bed actually spent sleeping = Sleep efficiency percentage (SE%). Average start time of the longest sleep period = average of sleep onset time)

The UCG pharmacy provided the participants with standard care for sleep disorders, based on the usual practice in the community pharmacy in Australia.[21] The UCG pharmacy also followed-up the participants after 2 weeks from baseline.

Baseline, monitoring, and follow-up

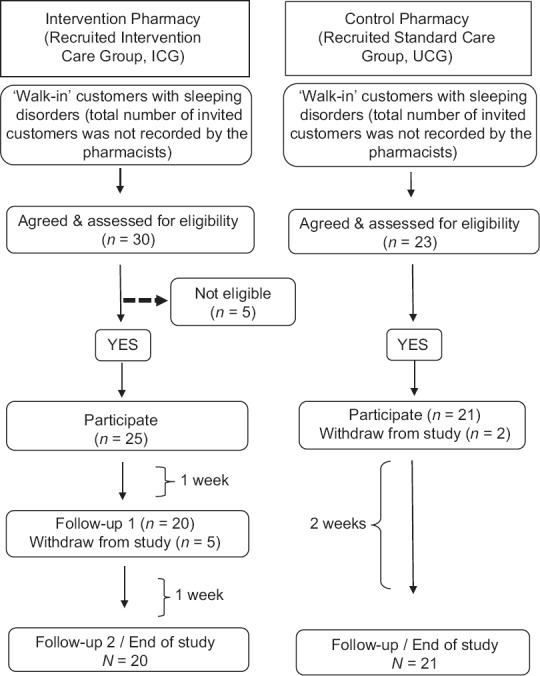

The complete duration of the study was 2 weeks [Figure 3]. The participants were conveniently assigned to the ICG or UCG, depending on which recruited pharmacy they attended. Recruitment was conducted from February 1, 2013, until May 15, 2013, with the last 2-week follow-up session completed on May 30, 2013.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of participants’ recruitment and follow-up

All participants in both groups completed a set of baseline questionnaires. Each participant in the ICG received an “intervention package” consisting of: (1) A wrist actigraph, (2) a sleep diary and (3) educational information about sleep disorders, sleep health management, sleep hygiene, and healthy lifestyle to improve sleep, via access to a website, developed purposely for this study.[20]

In the ICG, follow-up sessions were conducted at two-time points to download the actigraphy data and generate an individual sleep report. This was used to validate participants’ self-reported sleep diary and assess the sleep/wake patterns, and to counsel them regarding sleep. Upon completion of the study, participants returned the actigraph and completed a set of study completion questionnaires. For the ICG, the protocol included referral to a general practitioner (if required), after 2 weeks of follow-up. Meanwhile, the UCG received standard care for sleep disorders with a follow-up at week 2, via email or mail, to complete a similar set of study completion questionnaire as the ICG.[20]

Assessment instruments

Actigraph

The ICG received the SBV2 Readiband™ (Fatigue Science, Honolulu) wrist-worn actigraph to record sleep/wake patterns. The device was worn 24 h/day for 7 days before the participants revisited the pharmacy for their first follow-up, and then for a further 7 days after the first follow-up before returning to the pharmacy for final assessment to complete the study. To determine the acceptability and feasibility of this device for use in home-based settings, a feasibility study was conducted.[22]

The hardware consists of an accelerometer with the sensitivity to continuously track wrist-movement and keep these data for further analyses. The actigraph was initialized to collect data in 1 min epochs. The collected data were then wirelessly downloaded to a computer for analyses using Nordic 2.4 GHz ANT transceiver. Data were analyzed using proprietary software (Fatigue Science, Honolulu) and individualized reports were automatically generated for each participant.

Sleep diary

Each ICG participant also received a sleep diary to self-record 14 days of sleep onset latency (SOL), number of nocturnal awakenings (NWAK) and total sleep time (TST), plus information related to sleep hygiene, sleep-related lifestyle, and other factors that might interrupted sleep.

Baseline questionnaires

All participants were required to complete a set of self-administered questionnaires, which included:

Demographic and sleep-related lifestyle information (sleep environment, smoking, alcohol consumption, and caffeinated drinks intake), modified from the validated Pharmacy Tool for Assessment of Sleep Health (POTASH) [13,23]

Sleep health assessment (adapted from the POTASH) – to assess sleep scale scores, utilizing the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) [24,25] and the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI).[26,27]

Study completion questionnaires

At week 2, to complete the study, the participants were required to complete a set of self-administered study completion questionnaires, which included similar assessment of sleep scale (ESS and ISI) scores in place.

Statistical analysis

Sleep parameters measurement, that is, sleep efficiency in percentage (SE%), TST, SOL, and NWAK for each participant obtained from the sleep diary and actigraphy sleep report, were averaged from all the data recorded during the 2-week period (recorded as “pre” (week 1) and “post” (week 2) mean scores). In this analysis, there was no discrimination between weekdays and weekend data. Sleep scale scores recorded at baseline and week 2 were averaged to mean scores for analysis. Data were analyzed using SPSS 20.0 for windows (IBM). Considering alpha level of 0.05 for all statistical tests, and using descriptive, paired t-test and independent t-test, demographic characteristics, sleep scale scores, and pairwise differences of sleep parameters mean scores between and within groups were compared.

Results

Demographic and sleep-related characteristics

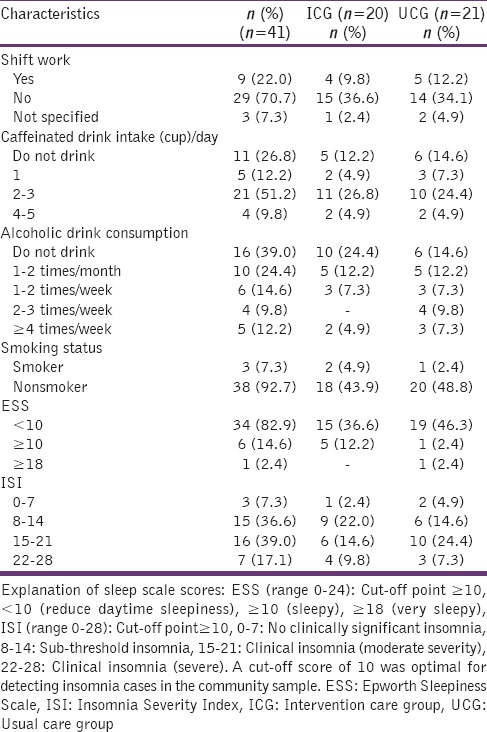

A total of forty-one (n = 41) customers participated and completed all parts of the study for analyses (ICG, n = 20; UCG, n = 21). The proportion of females was 68.3%. The predominant age group was between 46 and 60 years of age (36.6%) and followed by 31–45 years (24.4%). Almost half of the participants (48.8%) were college/university educated, and 29.3% were professional workers. In terms of ethnicity, most identified as Caucasian (53.7%), and followed by European (26.8%). Most participants (70.7%) were not working on shift, and 61% slept with a bed partner. The majority of participants (92.7%) were having difficulties sleeping (which puts them at higher risk of significant insomnia), but very few reported experiencing daytime sleepiness (17%). Table 1 shows the details of the participants’ sleep-related characteristics.

Table 1.

Baseline sleep-related characteristics of the participants

Effectiveness of the intervention

Assessments were based on these indicators:

Changes in mean scores for ESS and ISI, between and within groups, at baseline and week 2

Changes in mean scores for SE%, TST, NWAK, and SOL, between pre- and post-actigraphy sleep report data in the ICG.

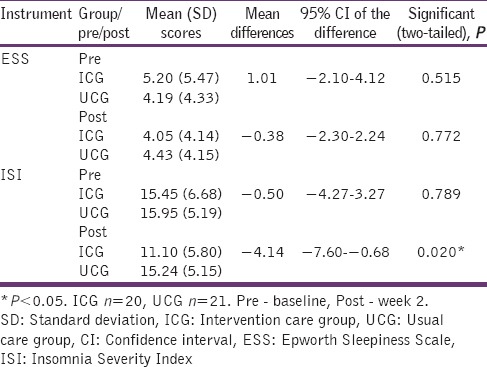

When comparing sleep scale mean scores between groups [Table 2], the ICG showed a lower post-ESS mean score compared to the UCG, although it was insignificant. However, a significant difference was found when comparing post-ISI mean scores between the ICG and the UCG. A marginal significant difference (P = 0.074) was found when comparing pre- and post-ESS mean scores in the ICG [Table 3]. Meanwhile, comparisons of mean scores between pre- and post-ISI within the ICG observed significant differences.

Table 2.

Comparisons between groups for sleep scale scores

Table 3.

Comparisons within groups for sleep scale scores

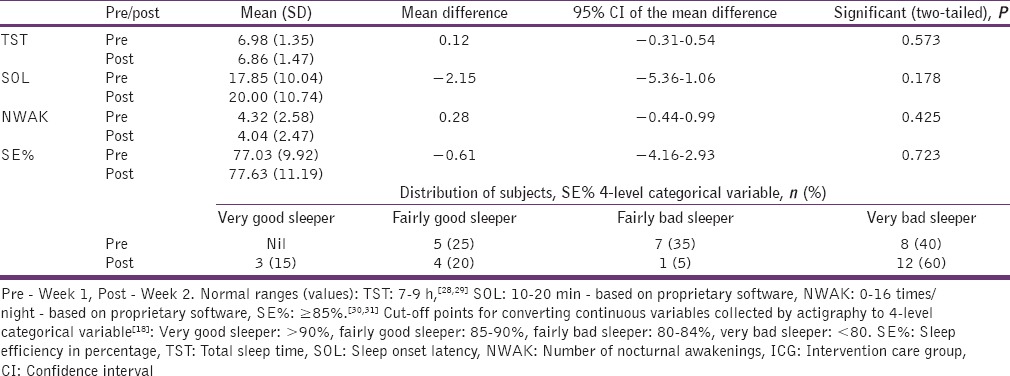

Comparisons of these mean scores (SE%, TST, SOL, and NWAK), assessed at two-time points in the ICG; showed no significant differences at all times. However, to better understand changes in SE%, it was categorized into 4-levels[18] [Table 4], and a slight increase was found in the number of subjects who rated themselves as “good sleepers” at post-assessment.

Table 4.

Comparisons of SE%, TST, SOL and NWAK mean scores in actigraphy assessments at two time points in the ICG (n=20)

Role of actigraph

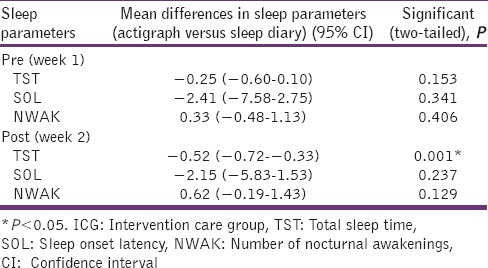

To evaluate the use of actigraph as an objective sleep assessment instrument, sleep parameter mean scores obtained from the actigraphy sleep report and the sleep diary were compared between groups at two-time points. The agreement was found between these two methods [Table 5].

Table 5.

Mean differences in sleep parameters of actigraph and sleep diary reported at two time points in the ICG (n=20)

Discussion

This study was developed to compare the standard care practice for managing sleep disorders in the community pharmacy with an intervention that utilized actigraph as an objective sleep assessment instrument to monitor and follow-up individuals with sleeping disorders after treatment was sought.

The insignificant findings for the ESS mean scores may be owing to the small number of participants who were at higher risk of excessive daytime sleepiness. However, in contrast, the differences between and within groups for ISI mean scores were observed at week 2. These results were consistent with other studies that used actigraph to assess insomnia patients.[17,32,33] Although the study initial aim was generally to focus on “poor sleep,” the majority of participants were found to be at higher risk of insomnia at baseline. Hence, the intervention appeared to be most effective in those with this condition. Another possible explanation is that in this study population, it could be easier to detect a difference due to a larger number of participants who were identified to be at risk of insomnia.

The intervention also included two consultation sessions, consisted of elements such as sleep education, sleep hygiene and discussion of sleep parameters (with actigraphy sleep reports forming the focus). The use of actigraphy sleep report during consultation especially in those with an insomnia-related disorder appears to have a positive impact. However, at this point there are no published studies of community pharmacy using actigraphy sleep reports during the consultation for sleep-related disorders; hence the results of this intervention could not be compared with similar situations and settings. However, this approach is almost similar to the “gold standard” treatment for insomnia, that is, the cognitive behavioral therapy (CBTI), which includes consultation to help patients change their sleep habits.[34] CBTI which combines elements such as sleep education, sleep hygiene, sleep restriction, and cognitive therapy is suggested to be effective in addressing the issues with sleep onset and maintenance of sleep in insomnia patients in primary healthcare settings.[35,36] One study which evaluated the effectiveness of CBTI (by evaluating changes in the ISI mean scores), found that the scores for the CBTI group was significantly reduced from pre-treatment to post-treatment.[37] Having significantly reduced mean scores for ISI in this study, the findings could suggest that this current study might be non-inferior to the study that used CBTI approach as an intervention. Although with a different setting and study population, this intervention study has shown that it is possible to adapt this approach into the community pharmacy workflow in providing an intervention that is more convenient and easier to conduct.

As part of the intervention, actigraph was also used to compare pre- and post-mean sleep parameters (SE%, TST, SOL, and NWAK) scores to identify changes in sleep/wake patterns in the ICG and evaluated the effectiveness of the intervention, as conducted in previous studies.[32,38,39] Although, as a whole, the findings could not observe significant differences, these are still need to be interpreted with caution as there may be significant discrepancies for some individuals, but was not observed in this study. The type of actigraph model and accompanying proprietary algorithm from the software, the sensitivity level and use of the non-dominant and dominant wrist, may also have affected the actigraphy results in this study.[33]

In research and clinical settings, the literature suggests combining actigraph monitoring with a sleep diary to better characterize sleep/wake patterns in individuals with disturbed sleep.[17,40] Similar sleep parameter results for SOL and NWAK found in both sleep diary and actigraphy data suggests that actigraph is an appropriate objective sleep assessment instrument to validate SOL and NWAK in this study. However, a significant difference was found when comparing post-TST mean scores between actigraphy data and sleep diary at week 2. This is in accordance with previous studies,[41,42] which found significant differences when comparing TST between these two tools.

Overall, actigraphy data revealed that mean scores for SE% were lower than the cut-off value at both pre- and post-assessment; suggesting that in the ICG, at both time points, the mean scores for SE% could not reach the expected level for a “good sleeper.” However, this study found a negative correlation between SE% and SOL, which meant that those who took longer to fall asleep (longer SOL) had a lower SE%. This correlation is supported by one study[43] that also found a negative correlation between sleep quality and SOL. However, to better confirm this, studies using actigraphy data from larger samples should be conducted.

Limitation

Due to its exploratory nature, one obvious limitation is the fact that the study has relatively small number of participants despite a priori power calculation. With a small sample size, caution must be applied, as the findings might not be transferable to the general community. However, the results could be used as representative of the customers experiencing certain sleep disorders attending the community pharmacy.

One more limitation is the time frame of the whole study. An extension of the study over a longer time frame would be supportive to test the hypotheses. With a longer time frame to recruit the participants, recruitment of a larger sample size would be possible. The challenges also were due to constraints outside of the research team's control, such as difficulties in recruiting the community pharmacies and participants within the time frame.

Another limitation is that the study was designed to recruit participants conveniently, and no randomization was conducted. The participants in the intervention group were aware of the intervention hence some of them might have reacted according to the researcher's expectation. This can be explained as “Hawthorne effect;” a phenomenon which suggests that study subjects’ behavior are altered by the subjects’ awareness that they are being studied or that they received additional attention.[44]

Conclusion

Although the intervention had limited success with regards to participant outcomes, it has offered some insights into the development of a community pharmacy-based intervention to improve the management of sleep disorders in the future. The study demonstrated that actigraphy is a method that is convenient to be used at the community pharmacy and the use of actigraphy sleep reports in generating objective sleep/wake data to assist the pharmacists during consultation sessions related to sleeping disorders, can positively provide support. The findings from this study have important implications for recommending further research using a larger sample size and different study populations, before the effectiveness of the “model of care” can be clearly understood. This study hence concluded that for a community-based intervention to be effective, and yet be able to be widely implemented, it needs to be practical, convenient for use and, easily conducted and implemented by the pharmacists and pharmacy staff.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Terry White and Malouf Pharmacies study teams for their assistance. ZMN is supported by the Ministry of Education Malaysia (MOE) scholarship and International Islamic University Malaysia (IIUM) scholarship to conduct research for a Ph.D. degree at the University of Queensland, Australia. The author also wishes to thank the School of Pharmacy University of Queensland for providing facilities and funding the resources for the study.

References

- 1.Kingston ACT: Deloitte Access Economics Pty Ltd; 2011. [Last cited on 2012 Jul 09]. Sleep Health Foundation. Re-awakening Australia: The Economic Cost of Sleep Disorders in Australia, 2010. Available from: http://www.sleephealthfoundation.org.au/pdfs/news/Reawakening%20Australia.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Australia: Access Economics; 2004. [Last cited on 2011 Mar 21]. Sleep Health Australia. Wake up Australia: The Value of Healthy Sleep. Available from: http://www.sleep.org.au/documents/item/69 . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hillman DR, Murphy AS, Pezzullo L. The economic cost of sleep disorders. Sleep. 2006;29:299–305. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lack L, Miller W, Turner D. A survey of sleeping difficulties in an Australian population. Community Health Stud. 1988;12:200–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.1988.tb00161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohayon MM, Roth T. Prevalence of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder in the general population. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:547–54. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00443-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Washington, DC: National Sleep Foundation; 2000. [Last cited on 2011 Jul 20]. National Sleep Foundation. Adolescents Sleep Needs and Patterns. Available from: http://www.sleepfoundation.org/sites/default/files/sleep_and_teens_report1.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asplund R. Nocturia: Consequences for sleep and daytime activities and associated risks. Eur Urol Suppl. 2005;3:24–32. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colten R, Altevogt M. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2006. Sleep Disorders and Sleep Deprivation: An Unmet Public Health Problem. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chai-Coetzer CL, Antic NA, Rowland LS, Reed RL, Esterman A, Catcheside PG, et al. Primary care vs specialist sleep center management of obstructive sleep apnea and daytime sleepiness and quality of life: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;309:997–1004. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holland R, Brooksby I, Lenaghan E, Ashton K, Hay L, Smith R, et al. Effectiveness of visits from community pharmacists for patients with heart failure: HeartMed randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2007;334:1098. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39164.568183.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hersberger KE, Renggli VP, Nirkko AC, Mathis J, Schwegler K, Bloch KE. Screening for sleep disorders in community pharmacies – Evaluation of a campaign in Switzerland. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2006;31:35–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2006.00698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwegler K, Klaghofer R, Nirkko AC, Mathis J, Hersberger KE, Bloch KE. Sleep and wakefulness disturbances in Swiss pharmacy customers. Swiss Med Wkly. 2006;136:149–54. doi: 10.4414/smw.2006.11265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tran A, Fuller JM, Wong KK, Krass I, Grunstein R, Saini B. The development of a sleep disorder screening program in Australian community pharmacies. Pharm World Sci. 2009;31:473–80. doi: 10.1007/s11096-009-9301-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kashyap K, Nissen L, Smith S, Douglas J, Kyle G. Can a community pharmacy sleep assessment tool aid the identification of patients at risk of sleep disorders in the community: A pilot study. Integr Pharm Res Pract. 2012;1:3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ancoli-Israel S, Cole R, Alessi C, Chambers M, Moorcroft W, Pollak CP. The role of actigraphy in the study of sleep and circadian rhythms. Sleep. 2003;26:342–92. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Souza L, Benedito-Silva AA, Pires ML, Poyares D, Tufik S, Calil HM. Further validation of actigraphy for sleep studies. Sleep. 2003;26:81–5. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vallières A, Morin CM. Actigraphy in the assessment of insomnia. Sleep. 2003;26:902–6. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.7.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Girschik J, Fritschi L, Heyworth J, Waters F. Validation of self-reported sleep against actigraphy. J Epidemiol. 2012;22:462–8. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20120012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landis CA, Frey CA, Lentz MJ, Rothermel J, Buchwald D, Shaver JL. Self-reported sleep quality and fatigue correlates with actigraphy in midlife women with fibromyalgia. Nurs Res. 2003;52:140–7. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200305000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noor ZM, Smith AJ, Smith SS, Nissen LM. A study protocol: A community pharmacy-based intervention for improving the management of sleep disorders in the community settings. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:74. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. Professional Practice Standards. Ver. 4. Canberra: The Pharmaceutical Society of Australia; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noor ZM, Smith A, Smith S, Nissen L. Feasibility and acceptability of wrist actigraph in assessing sleep quality and sleep quantity: A home-based pilot study in healthy volunteers. Health. 2013;5(8A2):63–72. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saini B, Wong K, Krass I, Grunstein R. Sydney: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing; 2009. The Role of Pharmacists in Sleep Health – A Screening, Awareness and Monitoring Program. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: The Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14:540–5. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johns MW. Daytime sleepiness, snoring, and obstructive sleep apnea. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Chest. 1993;103:30–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.103.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2:297–307. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morin CM, Belleville G, Bélanger L, Ivers H. The Insomnia Severity Index: Psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep. 2011;34:601–8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.5.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Washington, DC: National Sleep Foundation; 2011. [Last cited on 2013 Mar 23]. National Sleep Foundation. Fatigue and Excessive Sleepiness. Available from: http://www.sleepfoundation.org/article/sleep-related-problems/excessive-sleepiness-and-sleep . [Google Scholar]

- 29.Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2012. [Last cited on 2012 Mar 20]. American Psychological Association. Why Sleep is Important and What Happens When You Don’t Get Enough. Available from: http://www.apa.org/topics/sleep/why.aspx . [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Donoghue GM, Fox N, Heneghan C, Hurley DA. Objective and subjective assessment of sleep in chronic low back pain patients compared with healthy age and gender matched controls: A pilot study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:122. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-10-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lichstein KL, Stone KC, Donaldson J, Nau SD, Soeffing JP, Murray D, et al. Actigraphy validation with insomnia. Sleep. 2006;29:232–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Natale V, Plazzi G, Martoni M. Actigraphy in the assessment of insomnia: A quantitative approach. Sleep. 2009;32:767–71. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.6.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Washington, DC: National Sleep Foundation; 2011. [Last cited on 2012 Dec 14]. National Sleep Foundation. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia. Available from: http://www.sleepfoundation.org/article/hot-topics/cognitive-behavioral-therapy-insomnia . [Google Scholar]

- 35.Edinger JD, Wohlgemuth WK, Radtke RA, Marsh GR, Quillian RE. Cognitive behavioral therapy for treatment of chronic primary insomnia: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285:1856–64. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.14.1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Montgomery P, Dennis J. A systematic review of non-pharmacological therapies for sleep problems in later life. Sleep Med Rev. 2004;8:47–62. doi: 10.1016/S1087-0792(03)00026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jansson-Fröjmark M, Linton SJ, Flink IK, Granberg S, Danermark B, Norell-Clarke A. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia co-morbid with hearing impairment: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2012;19:224–34. doi: 10.1007/s10880-011-9275-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hedner J, Pillar G, Pittman SD, Zou D, Grote L, White DP. A novel adaptive wrist actigraphy algorithm for sleep-wake assessment in sleep apnea patients. Sleep. 2004;27:1560–6. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.8.1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blackwell T, Redline S, Ancoli-Israel S, Schneider JL, Surovec S, Johnson NL, et al. Comparison of sleep parameters from actigraphy and polysomnography in older women: The SOF study. Sleep. 2008;31:283–91. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.2.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gross CR, Kreitzer MJ, Reilly-Spong M, Wall M, Winbush NY, Patterson R, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction vs. Pharmacotherapy for primary chronic insomnia: A pilot randomized controlled clinical trial. Explore (NY) 2011;7:76–87. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Den Berg JF, Van Rooij FJ, Vos H, Tulen JH, Hofman A, Miedema HM, et al. Disagreement between subjective and actigraphic measures of sleep duration in a population-based study of elderly persons. J Sleep Res. 2008;17:295–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCall C, McCall WV. Comparison of actigraphy with polysomnography and sleep logs in depressed insomniacs. J Sleep Res. 2012;21:122–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2011.00917.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Augner C. Associations of subjective sleep quality with depression score, anxiety, physical symptoms and sleep onset latency in students. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2011;19:115–7. doi: 10.21101/cejph.a3647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fernald DH, Coombs L, DeAlleaume L, West D, Parnes B. An assessment of the Hawthorne effect in practice-based research. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25:83–6. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2012.01.110019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]