Abstract

Objective:

The purpose of this study was to investigate the association between knowledge and attitude with health-related quality of life (HRQoL) among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional descriptive study was undertaken with a cohort of 75 patients attending the University Diabetic Center at King Abdulaziz University Hospital, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The EuroQoL-five-dimensional (EQ-5D) scale was used to assess HRQoL. EQ-5D was scored using values derived from the UK general population survey. The brief diabetic knowledge test in questionnaire format developed by the University of Michigan Diabetes Research and Training Center and the attitude toward self-care questionnaire based on the diabetic care profile were used.

Results:

Fifty-eight (77.35%) respondents were male with a mean 12.6 ± 8.4 years of a history of diabetes. Thirty-four (45.3%) were in the age group of 45–55 years with a mean age of 54 ± 9.2 years. A moderate level of HRQoL (0.71 ± 0.22) was recorded in the study cohort. The mean EQ-5D score was lower in females compared to male patients (0.58 ± 0.23 vs. 0.74 ± 0.20). The mean score of Michigan Diabetic Knowledge Test was 8.96 ± 2.1 and the median score was 9.00. Of 75 diabetic patients, 14.7% had poor knowledge; 72% had moderate knowledge, and only 13.3% had good knowledge. The average attitude score of all respondents was 6.38 ± 2.11. There was a significant positive association between attitude and EQ-5D score.

Conclusion:

HRQoL and knowledge scores were moderate in type 2 diabetic patients in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Patient attitude toward the disease was positive, and this was positively associated with HRQoL; most respondents believed they are responsible for their care. It is likely that a high quality of diabetes self-management education program will provide benefits and affect significantly on type 2 diabetes patients in Saudi Arabia.

KEY WORDS: Attitude, diabetes, knowledge, quality of life, Saudi Arabia

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a disease of global epidemic proportions, especially prevalent in countries undergoing socioeconomic transformation. The World Health Organization has estimated that the prevalence of diabetes was171 million; this number is forecasted to reach 300 million by 2030.[1,2]

Type 2 is the most common type of diabetes, seen in around 90–95% of the diabetic population.[3] It is associated with morbidity and mortality, which affects patients’ general health and well-being and it is, therefore, regarded as a major public health problem.[4] In addition, younger age groups, striking younger adults and the adolescents is affecting also by type 2 diabetes.[5] A defect in insulin action causes type 2 diabetes and this puts patients at risk of increased macro-vascular and micro-vascular complications, which in turn lead to a reduction in health-related quality of life (HRQoL).[6] Within this context, Saudi Arabia is a developing country where DM is a major clinical and public health problem. Al-Nozha et al. reported that 23.7% of the Saudi population has diabetes; the male prevalence is 26.2% while the female prevalence is 21.5%.[7]

HRQoL has been recognized as an essential health outcome; indeed, it is represented as the ultimate goal among various health outcomes.[8] It is defined as patient perceived physical, emotional, and social well-being.[9] Healthcare professionals have used HRQoL to demonstrate factors that affect human health status.[10] It has been reported that diabetic patients have associated with more diabetic complications and lower HRQoL than nondiabetic patients.[11] Redekop et al. conducted study of 1348 type 2 diabetic patients as part of a larger European study Cost of Diabetes in Europe-type 2 and reported that complications and obesity were associated with lower HRQoL.[12] A cross-sectional study was conducted in five primary healthcare center in Saudi Arabia by Al-shehri et al. to determine HRQoL using different instrument of the short form health survey (SF-12) and found that the HRQoL of type 2 diabetic patients was significantly lower than nondiabetic patients. In addition, patients with controlled diabetes had better HRQoL than uncontrolled diabetic patients.[13]

Several studies have showed that self-management of diabetes has a positive effect on glycemic control.[14,15] The acquisition of diabetic knowledge is recognized as an important factor contributing to the improvement of changes in self-care (SC) behavior.[16] Long-term diabetes complications have an adverse effect on the quality of life[17,18] and there is evidence that self-management of diabetes, with consequent improved glycemic control, results in a significantly reduced progression of complications and hence, an improved HRQoL of diabetic patients.[19]

Diabetic knowledge alone is not sufficient for diabetic patients to influence change in their lifestyle; the relationship between knowledge and lifestyle change has been effected by attitude, as a psychological variable for diabetic patients.[20] Diabetic patients also need to increase their attitude and self-efficacy to the improvement of glycemic control; this will lead to an increase their HRQoL.[21]

Although the prevalence of DM in the Saudi population is high, patients tend to lack knowledge about their condition and how to care for themselves.[22,23,24] The lack of proper diabetes education and awareness programs in Saudi Arabia exacerbates gaps in knowledge and inadequacies in compliance, and also inadequacies in self-management, which affects glycemic control.[23] There are, however, few studies regarding the effects of diabetic patients’ knowledge and attitudes on HRQoL; it is, nevertheless, important to understand more about the effects of knowledge and attitudes on HRQoL. The aim of this study is to assess the association between knowledge, attitudes, and HRQoL among type 2 DM (T2DM) in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Materials and Methods

Study design and selection of participants

A descriptive, cross-sectional study was conducted to assess associations between diabetes knowledge and diabetes attitudes, and HRQoL in type 2 diabetic patients attending the University Diabetic Center in King Abdulaziz University Hospital, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Seventy-five eligible subjects participated in this study from April to July 2012.[25]

Patients aged 18 years and above, with a confirmed diagnosis of T2DM and willing to participate were included in this study. Patients who were pregnant or planning to become pregnant, or with documented psychological problems, mental illness, or renal failure were excluded from the study. All patients meeting the inclusion criteria were invited to participate in the study. All who agreed to participate were asked to sign a written informed consent form.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) Committee of the College of Medicine, King Saudi University (IRB number: E-12-571).

Data collection and instruments

Data were obtained using questionnaires completed during face-to-face interviews. Sociodemographic data were collected, including gender, age, marital status, job type, duration of disease, and type of treatment. The EuroQoL-five-dimensional (EQ-5D) scale was used to assess HRQoL. EQ-5D was scored using values derived from the UK general population survey. The brief diabetic knowledge test in questionnaire format developed by the University of Michigan Diabetes Research and Training Centre (MDRTC) and the attitude toward SC questionnaire based on the diabetic care profile were used.

The original questionnaires of diabetic knowledge test were available in English and were translated into Arabic by a bilingual professional translator working in the strategies Center for Diabetes Research of the Diabetic Center, King Abdulaziz University Hospital. The Arabic version was revised and then back translated into English by another bilingual translator, and then retranslated into Arabic. This Arabic version of the MDTRC was examined and approved by two diabetologists to assess content and construct validity. EuroQol provided the Arabic version of the EQ-5D questionnaire. The reliability and validity of the questionnaires were tested among 15 patients during the pilot study to expose any difficulties in understanding the theme and the meaning of the questions. The Cronbach's alpha value for the 14 items of Michigan Diabetic Knowledge Test (MDKT) was (α = 0.66). The Cronbach's alpha values for the EQ-5D and attitude were (α = 0.83 and 0.74), respectively.

Assessment of knowledge about diabetes

The brief diabetic knowledge test, developed by the MDRTC was used to assess the degree of knowledge that patients with type 2 diabetes possessed about their diabetes.[26] It is known as the Michigan Diabetic Knowledge Test (MDKT) and comprises 14 multiple-choice items. Each patient was asked to choose one possible answer for each of the questions. Each correct answer scored one point; an incorrect answer scored zero. The knowledge test scores ranged from 0 to 14 where 14 represented the highest level of knowledge of diabetes and zero represented the lowest. We considered that a knowledge score of <7 constituted poor knowledge; 7–11 moderate knowledge; and 12–14 good knowledge.[27]

Assessment of attitude

The attitude toward SC was measured using the diabetic care profile, which was developed by the University of Michigan. This questionnaire includes 10 questions on to assess patient attitude toward diabetes. All items were scored according to five subscales: 1 - strongly disagree (SD); 2 - disagree (DA); 3 - neutral; 4 - agree; 5 - strongly agree (SA).[28]

Assessment of health-related quality of life

The EQ-5D is a well-known generic instrument consisting of two parts that were developed by the EuroQol group to measure HRQoL.[29] It produces a single descriptive profile and a single index value that represents the health status of each patient. It can be used for economic evaluation studies, such as cost-effectiveness analyses.[30] The EQ-5D involves patient self-reporting of their health status in terms of five dimensions: mobility; SC; usual activities; pain/discomfort; and anxiety/depression. HRQoL is measured in terms of three levels of severity with regard to the reported functional state for each dimension (no problems, some or moderate problems, and extreme problems). Five digit codes for the HRQoL of each patient were obtained from the score digits that resulted in 243 possible unique sets of health status, which could be produced by the descriptive system of the EQ-5D instrument.[31] The set of possible values yields a range of scores between 0 and 1, where 1 represents a state of perfect health; 0 represents death; and scores of <represents a state of health perceived to be worse than death. The second part of the EQ-5D consists of 20 cm visual analog scales (VAS) with endpoints of 0 denoting the worse imaginable state and 100 denoting the best state of health; this is used to record the subject's perception of his or her quality of life.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics was calculated using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (version 22.00). All statistical tests were performed using 0.05 as the level of significance. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and median ± interquartile range, while categorical variables were presented as absolute numbers and percentages. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for parametric variables and the Kruskal–Wallis test for nonparametric variables were used to test the significance of differences between more than two groups; the Mann–Whitney U-test and independent samples t-test were used to test significant differences between two groups. Relationships between the diabetic knowledge score, HRQoL and attitude were explored using Pearson's rank correlation and Spearman's rank correlation coefficient tests for parametric and nonparametric data, respectively.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants

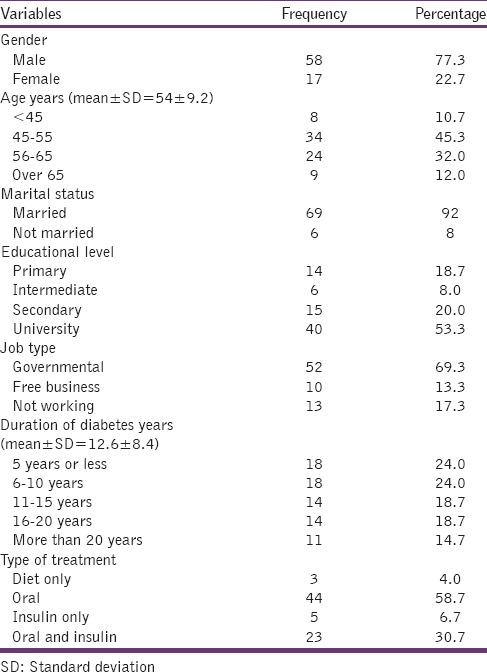

The demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. Among 75 diabetic patients, the mean age (SD) was 54 ± 9.2 years; 77.3% were male. The mean duration of diabetes was 12.6 ± 8.4 years. Ninety-two percentage (n = 69) of the participants were married. About 53.3% (n = 40) had a university level of education and 69.3% (n = 52) were employed by the government. More than half (58.7%) were taking oral hypoglycemic agents.

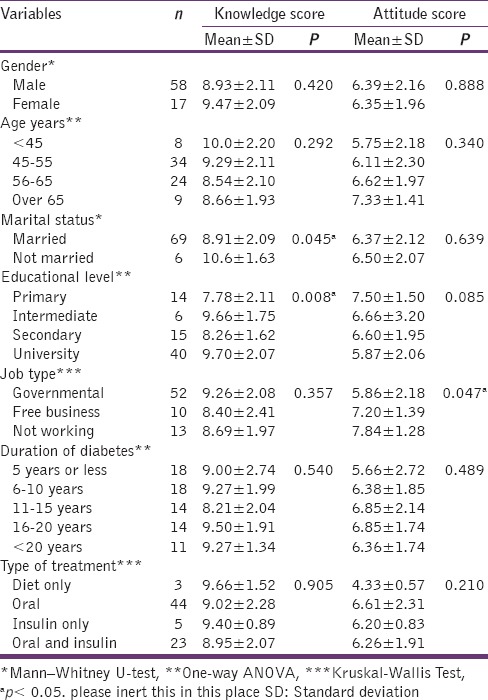

Table 1.

Characteristics of the patients

Assessment of health-related quality of life scores

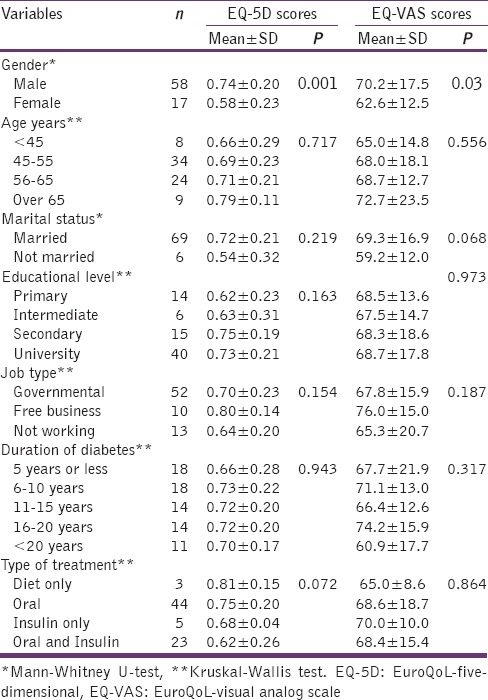

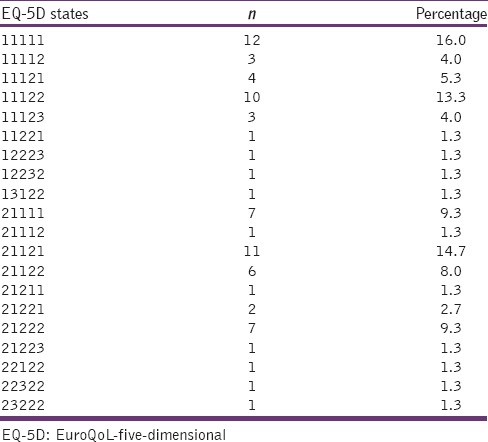

Table 2 reports that the mean scores of EQ-5D and EQ-VAS were 0.71 ± 0.22 and 68.5 ± 16.8, respectively. There were statistically significant differences between the genders regarding the mean scores of both EQ-5D and EQ-VAS, respectively (P = 0.001), (P = 0.03). Females had lower mean scores than male patients (0.58 ± 023 vs. 0.74 ± 0.20 for EQ-5D and 62.6 vs. 70.2 for EQ-VAS). Married patients had a higher HRQoL than unmarried, but the difference was not significant. There was a significant correlation between EQ-5D and EQ-VAS scores (correlation coefficient 0.455, P < 0.001). The majority of the diabetic patients in this study (n = 12, 16.6%) reported their health status as 1111, that indicated that no problems existed in any of the five domains, as shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

Demographic and illness characteristics of the study patients with differences in EQ-5D and EQ-VAS

Table 3.

Frequency of self-reported (EQ-5D) health states

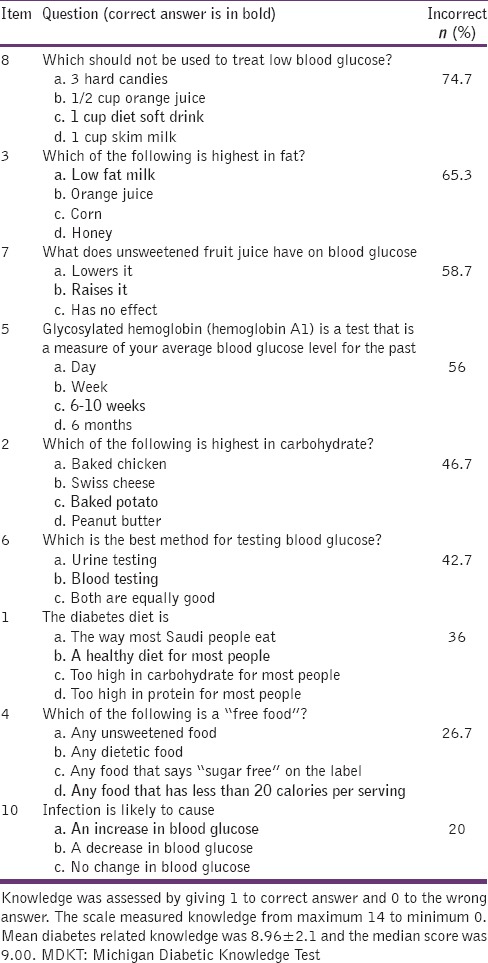

Assessment of knowledge scores

The mean score of the MDKT was 8.96 ± 2.1 and the median score was 9.00, indicating that, overall, the patients had moderate knowledge about diabetes. Diabetes-related knowledge, as reported by the study respondents, is further described Table 4 that demonstrates the MDKT questions that were answered correctly or incorrectly. Out of 75 diabetic patients, 14.7% demonstrated poor knowledge, 72% moderate knowledge, and only 13.3% good knowledge. Poor knowledge was most apparent in response to the questions related to food that should not be used when blood glucose was low (74.7% were incorrect). Questions regarding which foods contained the most fat also tended to be answered incorrectly (65.3% were incorrect); the effect of unsweetened fruit juice on blood sugar (58.7% were incorrect); and 56% incorrectly answered the question related to glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c). However, in questions 2, 6, 1, 4, and 10 the incorrect answer rates were only 46.7%, 42.7%, 36%, 26.7%, and 20%, respectively.

Table 4.

Percentage of correct and incorrect answer of study patients for the MDKT

Diabetes knowledge and demographic characteristics

Table 5 shows the relationship between MDKT scores and participants’ sociodemographic characteristics. One-way ANOVA revealed a significant relationship between MDKT scores and educational level (F = 4.606, df = 3.00, P = 0.008). The MDKT scores increased as the educational level increased; the MDKT scores in university level were higher than the primary level of education (9.70 ± 2.07 vs. 7.78 ± 2.11). There is a significant difference in knowledge score between marital status by using Mann–Whitney test (P = 0.045). Patients who were not married had higher scores than married (8.91 ± 2.09 vs. 10.66 ± 1.63).

Table 5.

Demographic and illness characteristics of the study patients with differences in knowledge and attitude scores

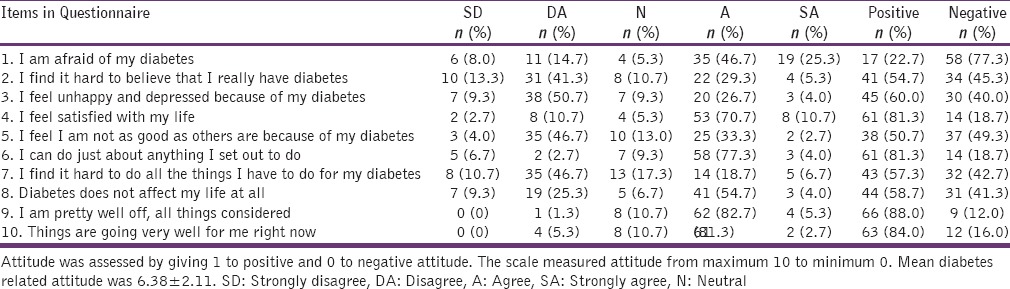

Attitude assessment

Table 6 displays the number and percentages of respondents who reported positive or negative attitudes to each item on the attitude questionnaire. For items, 1, 2, 3, 5, and 7 the options SD and DA related to a positive attitude; for items 4, 6, 8, 9, and 10 the options agree (A) and SA related to a positive attitude. Most respondents 58 (77.3%) were afraid of their condition. Only 30 (40.0%) felt unhappy and depressed because of diabetes. Sixty-one patients (81.3%) felt satisfied with their life and felt they could do anything that they set out to do concerning their diabetes. Only 34 (45.3%) said it was difficult to believe they were suffering from diabetes. In addition, 32 (42.7%) found it hard to carry out all the practices related to the disease. However, 63 (84%) stated that, overall they were very well right now. Overall, the average attitude score of all respondents in this study was 6.38 ± 2.11.

Table 6.

Attitude towards diabetes as reported by study respondents

The correlation coefficient between EQ-5D and EQ-VAS scores was 0.455 (P < 0.001). Spearman's rank order correlation coefficient between attitude and EQ-5D scores was 0.299 (P = 0.009), while that between attitude and EQ-VAS scores was 0.197 (P = 0.091). The findings of the current study indicate a significant association between attitude and EQ-5D scores.

Discussion

HRQoL is one of the important outcomes used to evaluate the effect of management of chronic disease on health. Various studies have showed that the EQ-5D has been used to measure the HRQoL of diabetic patients.[12,32,33,34,35] In this study, the mean age of participants was 54 ± 9.2, which was similar to the patients in the study conducted in Saudi Arabia by Al-Tuwijri et al.[36] It is obvious from previous studies that type 2 diabetic patients have moderately lower scores of HRQoL than general populations of similar age.[8,37] In our study, the mean of EQ-5D score in type 2 diabetic patients was 0.71, which is considered a moderate score, consistent with other studies conducted in different countries that reported mean EQ-5D scores as 0.74, 0.69, 0.70, and 0.70.[12,37,38,39] The study findings showed that EQ-5D and EQ-VAS scores were lower in female, compared to male, patients. This corresponds to a number of previous study findings that reported that the HRQoL is higher among diabetic males than diabetic females.[12,33,34,40] This difference could be due to lifestyle behavior differences between men and women in Saudi society as women normally spent most of their time in their houses; this may lead to lower physical activity and bad habits regarding eating.[36]

Diabetic patients need to be knowledgeable in order to achieve better glycemic control and hence, improved HRQoL[14] However, 50–80% of individuals with diabetes have significantly poor levels of knowledge and skills.[15,41] In our study, the mean score of MDKT was 8.96, which indicated an average level of knowledge; this could be insufficient. This finding is in accordance with those of other studies also reporting an average level of knowledge.[16,42,43] The overall mean percentage of correct answers in the knowledge questionnaire in this study was 64.6%, which was higher than that reported by other studies.[27,44,45] However, Mufunda et al. and Murata et al. reported mean percentage knowledge scores of 64.9% and 63.8%, respectively, that were consistent with those found in our study. The overall knowledge score we report reveals that, although participants had a basic general knowledge of their diabetes, nevertheless, there were some defects in different areas of knowledge, particularly in relation to SC and diet.

The knowledge percentage score of questions about how to treat hypoglycemia by different diet choice was low. However, the phrasing of this item is slightly obscure and could lead to failure of the respondents to understand it, and a low percentage score. Our result is in accordance with other studies using the same instrument.[46,47] Knowledge scores were high regarding the two questions on foot care and exercise; this accords with the findings of other studies.[46,48] Diabetic patients in our study could manage their foot care and know about the positive effects of exercise on glycemic control. However, although patients know what to do, they do not always put this knowledge into practice.[49] Patients’ awareness about complications was relatively high in this study because they had experienced complications and thus recognize the importance of the consequences of complications, which may bring about a reduction in HRQoL.[12] Al-Maskari et al. conducted a study in the Emirates and reported that patients have considerable knowledge about the complications of diabetes, although major gaps in knowledge existed related to diet and how to manage hypoglycemia.[44] These findings agree with those of other studies.[27,46,47]

Most respondents in our study misunderstood some questions related to the highest fat-containing food and unsweetened fruit juice. Al-Adsani et al. showed that type 2 diabetic patients had poor knowledge about high-fat food and the effect of unsweetened fruit juice on blood glucose.[27] Only 44% of diabetic patients in this study correctly answered questions related to HBA1c; indeed, interviews revealed that most patients who incorrectly answered this question did not know what HbA1c is. HbA1c is an important and widely used marker of glycemic control. In this study, most patients did not possess knowledge about HbA1c, which is in accordance with a study conducted by Murata et al. among type 2 diabetic patients using the same MDKT; 56% of their respondents did not know about HbA1c.[46] Diabetic patients possessing knowledge about HbA1c were shown to have a better understanding of SC and good regulation of their blood glucose.[50]

The results of this study revealed that the knowledge scores of diabetic patients were significantly associated with their educational level. This finding was consistent with those from several other studies.[22,27,46,48,51,52,53,54,55,56] Diabetic patients in this study with a higher educational level and better socioeconomic status have more chance of gaining knowledge and information about diabetes from different sources such as books, the press and other mass media. They can communicate with health providers without barriers and are more likely to acquire accurate information. Patients with a low level of education were unable to self-manage their disease and so their diabetic outcome was worse. It is difficult for patients of a low educational level to communicate with health providers; these patients might need to have these obstacles removed to improve communication and increase the effectiveness of self-management education.[27,57,58]

Knowledge scores were significantly associated with marital status; this result accords with that of Persell et al.[56] Neither gender nor age group was associated with knowledge score. Findings regarding the association between knowledge score and gender are, however, conflicting. While some studies reported that knowledge, scores were higher in females than in males, this might be related to the observation that women have a greater ability to learn.[46] Other studies have reported that women had lower scores suggesting that women need more intensive health education programs.[59] Low knowledge scores were found in older rather than younger diabetic patients; this finding is congruent with those of other studies.[22,53]

This study evaluated the attitudes toward SC using a diabetic care profile developed by the University of Michigan. Most respondents reported the negative attitude of being afraid of their disease, but also expressed the positive attitude of feeling satisfied with their life. Furthermore, a greater proportion of the patients said it was difficult for them to believe that they had diabetes, which is a negative attitude. However, the overall. The mean score of attitude in this study showed that diabetic patients had a positive attitude toward diabetes and these accords with the findings of a study conducted in India,[60] but contrasts with an Emirate study that reported that the majority of diabetic patients had a negative attitude.[44]

The main objective of this study was to assess the association between diabetic knowledge and attitude, with HRQoL in patients with type 2 diabetes. The results showed that HRQoL was associated with attitude, but there is no association between knowledge score and HRQoL. This finding was supported by Zabaleta et al. who reported that there is no association between diabetic knowledge and HRQoL.[16] HRQoL in this study was significantly associated with attitude toward diabetes, which is in line with the findings of.[61] This result revealed that patients with knowledge about their diabetes had improved HRQoL. This effect might be independent of the knowledge gained; however, the improvement of the quality of life might be related to other factors such as behaviour change[14,62] or metabolic control.[19,63]

Conclusion

HRQoL and knowledge scores of type 2 diabetic patients in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia were moderate. The HRQoL scores for males were higher than those of females and patients of a higher education level had more chance of gaining knowledge than less well-educated respondents. Diabetic knowledge was not associated with HRQoL. Patient attitude toward the disease was overall positive, which was associated with HRQoL; most participants believed that they are responsible for their care. This implies that diabetic patients will be ready to change if the diabetes self-management education program is adopted; this focuses on lifestyle and habit change as well as some areas of diabetes knowledge, particularly the skills needed to apply the knowledge to different practical situations.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Geneva: WHO; 2000. [Last accessed on 2015 Jan 20]. World Health Organization and Fact Sheet No. 138. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs312/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.King H, Aubert RE, Herman WH. Global burden of diabetes, 1995-2025: Prevalence, numerical estimates, and projections. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1414–31. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.9.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:S64–71. doi: 10.2337/dc12-s064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.London: A King's Fund Report Commissioned by the British Diabetic Association King's Fund; 1996. The King's Fund Policy Institute. Counting the Cost: The Real Impact of Non Insulin Dependent Diabetes. [Google Scholar]

- 5.King H. WHO and the International Diabetes Federation: Regional partners. Bull World Health Organ. 1999;77:954. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akinci F, Yildirim A, Gözü H, Sargin H, Orbay E, Sargin M. Assessment of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of patients with type 2 diabetes in Turkey. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2008;79:117–23. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Nozha MM, Al-Maatouq MA, Al-Mazrou YY, Al-Harthi SS, Arafah MR, Khalil MZ, et al. Diabetes mellitus in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2004;25:1603–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rubin RR, Peyrot M. Quality of life and diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 1999;15:205–18. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-7560(199905/06)15:3<205::aid-dmrr29>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Testa MA, Simonson DC. Assesment of quality-of-life outcomes. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:835–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603283341306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saleem F, Hassali MA, Shafie AA. A cross-sectional assessment of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) among hypertensive patients in Pakistan. Health Expect. 2014;17:388–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2012.00765.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang XH, Wee HL, Tan K, Thumboo J, Li SC. Is diabetes knowledge associated with health-related quality of life among subjects with diabetes. A preliminary cross-sectional convenience-sampling survey study among English-speaking diabetic subjects in Singapore? J Chin Clin Med. 2009;4:144–50. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Redekop WK, Koopmanschap MA, Stolk RP, Rutten GE, Wolffenbuttel BH, Niessen LW. Health-related quality of life and treatment satisfaction in Dutch patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:458–63. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Shehri AH, Taha AZ, Bahnassy AA, Salah M. Health-related quality of life in type 2 diabetic patients. Ann Saudi Med. 2008;28:352–60. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2008.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aghamolaei T, Eftekhar H, Mohammad K, Nakhjavan M, Shojaeizadeh D, Ghofranipour F, et al. Effects of a health education program on behavior, HbA1c and health-related quality of life in diabetic patients. Acta Med Iran. 2005;43:89–94. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norris SL, Engelgau MM, Narayan KM. Effectiveness of self-management training in type 2 diabetes: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:561–87. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.3.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zabaleta A, Forbes A, While A, Mold F, Armayor NC. Relationship between diabetes knowledge, glycaemic control and quality of life: Pilot study. Prim Care Diabetes. 2010;12:374–81. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grandy S, Fox KM. EQ-5D visual analog scale and utility index values in individuals with diabetes and at risk for diabetes: Findings from the Study to Help Improve Early evaluation and management of risk factors Leading to Diabetes (SHIELD) Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:18. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamadeh RR. Noncommunicable diseases among the Bahraini population: A review. East Mediterr Health J. 2000;6:1091–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lau CY, Qureshi AK, Scott SG. Association between glycaemic control and quality of life in diabetes mellitus. J Postgrad Med. 2004;50:189–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ardena GJ, Paz-Pacheco E, Jimeno CA, Lantion-Ang FL, Paterno E, Juban N. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of persons with type 2 diabetes in a rural community: Phase I of the community-based diabetes self-management education (DSME) program in San Juan, Batangas, Philippines. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;90:160–6. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grey M, Boland EA, Davidson M, Li J, Tamborlane WV. Coping skills training for youth with diabetes mellitus has long-lasting effects on metabolic control and quality of life. J Pediatr. 2000;137:107–13. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.106568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aljoudi AS, Taha AZ. Knowledge of diabetes risk factors and preventive measures among attendees of a primary care center in Eastern Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 2009;29:15–9. doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.51813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saadia Z, Rushdi S, Alsheha M, Saeed H, Rajab M. A study of knowledge attitude and practices of Saudi women towards diabetes mellitus. A (KAP) study in Al-Qassim region. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2010;11:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uddin I, Ahmad TJ, Kurkuman AR, Iftikhar R. Diabetes education: Its effects on glycemic control. Ann Saudi Med. 2001;21:120–2. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2001.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dawson B, Robert GT. 4th ed. Singapore: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2004. Basic and Clinical Biostatistics; pp. 154–7. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fitzgerald JT, Funnell MM, Hess GE, Barr PA, Anderson RM, Hiss RG, et al. The reliability and validity of a brief diabetes knowledge test. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:706–10. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.5.706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al-Adsani AM, Moussa MA, Al-Jasem LI, Abdella NA, Al-Hamad NM. The level and determinants of diabetes knowledge in Kuwaiti adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2009;35:121–8. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fitzgerald JT, Davis WK, Connell CM, Hess GE, Funnell MM, Hiss RG. Development and validation of the Diabetes Care Profile. Eval Health Prof. 1996;19:208–30. doi: 10.1177/016327879601900205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kind P. The EuroQol instrument: An index of health-related quality of life. Q Life Pharmacoecon Clin Trials. 1996;2:191–201. [Google Scholar]

- 30.EuroQol Group. EuroQol – A new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dolan P. Modeling valuations for EuroQol health states. Med Care. 1997;35:1095–108. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199711000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi YJ, Lee MS, An SY, Kim TH, Han SJ, Kim HJ, et al. The relationship between diabetes mellitus and health-related quality of life in Korean adults: The Fourth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2007-2009) Diabetes Metab J. 2011;35:587–94. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2011.35.6.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee WJ, Song KH, Noh JH, Choi YJ, Jo MW. Health-related quality of life using the EuroQol 5D questionnaire in Korean patients with type 2 diabetes. J Korean Med Sci. 2012;27:255–60. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2012.27.3.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakamaki H, Ikeda S, Ikegami N, Uchigata Y, Iwamoto Y, Origasa H, et al. Measurement of HRQL using EQ-5D in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Japan. Value Health. 2006;9:47–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2006.00080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Solli O, Stavem K, Kristiansen IS. Health-related quality of life in diabetes: The associations of complications with EQ-5D scores. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:18. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Al-Tuwijri AA, Al-Doghether MH, Akturk Z, Al-Megbil TI. Quality of life of people with diabetes attending primary care health centres in Riyadh: Bad control good quality? Qual Prim Care. 2007;15:307–14. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koopmanschap M. CODE. Advisory Board. Coping with type II diabetes: The patient's perspective. Diabetologia. 2002;45:S18–22. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-0861-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Javanbakht M, Abolhasani F, Mashayekhi A, Baradaran HR, Jahangiri Noudeh Y. Health related quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Iran: A national survey. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44526. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Reilly DJ, Xie F, Pullenayegum E, Gerstein HC, Greb J, Blackhouse GK, et al. Estimation of the impact of diabetes-related complications on health utilities for patients with type 2 diabetes in Ontario, Canada. Qual Life Res. 2011;20:939–43. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9828-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Quah JH, Luo N, Ng WY, How CH, Tay EG. Health-related quality of life is associated with diabetic complications, but not with short-term diabetic control in primary care. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2011;40:276–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clement S. Diabetes self-management education. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:1204–14. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.8.1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miloradovi D, Nikolic M, Dimic D, Branko B, Abramovic Z, Petrovic V. Knowledge, attitude and behaviour toward own disease among patients with type 2 diabetes. Prim Health Care. 2009;26:195–201. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mufunda E, Wikby K, Björn A, Hjelm K. Level and determinants of diabetes knowledge in patients with diabetes in Zimbabwe: A cross-sectional study. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;13:78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Al-Maskari F, El-Sadig M, Al-Kaabi JM, Afandi B, Nagelkerke N, Yeatts KB. Knowledge, attitude and practices of diabetic patients in the United Arab Emirates. PLoS One. 2013;8:e52857. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Al-Qazaz HK, Hassali MA, Shafie AA, Sulaiman SA, Sundram S. The 14-item Michigan diabetes knowledge test: Translation and validation study of the Malaysian version. Pract Diabetes Int. 2010;27:238–41a. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murata GH, Shah JH, Adam KD, Wendel CS, Bokhari SU, Solvas PA, et al. Factors affecting diabetes knowledge in type 2 diabetic veterans. Diabetologia. 2003;46:1170–8. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1161-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moodley LM, Rambiritch V. An assessment of the level of knowledge about diabetes mellitus among diabetic patients in a primary healthcare setting. S Afr Fam Pract. 2007;49:16–16d. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abdullah L, Margolis S, Townsend T. Primary health care patients’ knowledge about diabetes in the United Arab Emirates. East Mediterr Health J. 2001;7:662–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tankova T, Dakovska G, Koev D. Education of diabetic patients – a one year experience. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;43:139–45. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(00)00159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heisler M, Piette JD, Spencer M, Kieffer E, Vijan S. The relationship between knowledge of recent HbA1c values and diabetes care understanding and self-management. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:816–22. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.4.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Al-Qazaz HK, Sulaiman SA, Hassali MA, Shafie AA, Sundram S, Al-Nuri R, et al. Diabetes knowledge, medication adherence and glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes. Int J Clin Pharm. 2011;33:1028–35. doi: 10.1007/s11096-011-9582-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bruce DG, Davis WA, Cull CA, Davis TM. Diabetes education and knowledge in patients with type 2 diabetes from the community: The Fremantle Diabetes Study. J Diabetes Complications. 2003;17:82–9. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8727(02)00191-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gunay T, Ulusel B, Velipasaoglu S, Unal B, Ucku R, Ozgener N. Factors affecting adult knowledge of diabetes in Narlidere Health District, Turkey. Acta Diabetol. 2006;43:142–7. doi: 10.1007/s00592-006-0230-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.He X, Wharrad HJ. Diabetes knowledge and glycemic control among Chinese people with type 2 diabetes. Int Nurs Rev. 2007;54:280–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2007.00570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kamel NM, Badawy YA, el-Zeiny NA, Merdan IA. Sociodemographic determinants of management behaviour of diabetic patients. Part II. Diabetics’ knowledge of the disease and their management behaviour. East Mediterr Health J. 1999;5:974–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Persell SD, Keating NL, Landrum MB, Landon BE, Ayanian JZ, Borbas C, et al. Relationship of diabetes-specific knowledge to self-management activities, ambulatory preventive care, and metabolic outcomes. Prev Med. 2004;39:746–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Powell CK, Hill EG, Clancy DE. The relationship between health literacy and diabetes knowledge and readiness to take health actions. Diabetes Educ. 2007;33:144–51. doi: 10.1177/0145721706297452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schillinger D, Bindman A, Wang F, Stewart A, Piette J. Functional health literacy and the quality of physician-patient communication among diabetes patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;52:315–23. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00107-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hawthorne K, Tomlinson S. Pakistani moslems with Type 2 diabetes mellitus: Effect of sex, literacy skills, known diabetic complications and place of care on diabetic knowledge, reported self-monitoring management and glycaemic control. Diabet Med. 1999;16:591–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.1999.00102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hawal NP, Shivaswamy MS, Kambar S, Patil S, Hiremath MB. Knowledge, attitude and behaviour regarding self-care practices among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients residing in an urban area of South India. Int Multidiscip Res J. 2013;2:31–5. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rose M, Fliege H, Hildebrandt M, Schirop T, Klapp BF. The network of psychological variables in patients with diabetes and their importance for quality of life and metabolic control. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:35–42. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li C, Ford ES, Mokdad AH, Jiles R, Giles WH. Clustering of multiple healthy lifestyle habits and health-related quality of life among U.S. adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1770–6. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wattana C, Srisuphan W, Pothiban L, Upchurch SL. Effects of a diabetes self-management program on glycemic control, coronary heart disease risk, and quality of life among Thai patients with type 2 diabetes. Nurs Health Sci. 2007;9:135–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2007.00315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]