Abstract

Objectives:

The objectives of this study were to assess the general public views and familiarity toward electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) in Kuantan, Malaysia.

Methodology:

A total of 277 Kuantan people were involved in this study. The questionnaire was distributed at random in shops, businesses, and public places in Kuantan. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (version 17.0).

Results:

From 400 participants, a total number of 277 (160, 57.7% men and 117, 42.4% women) respondents completed the questionnaire. The mean age was 26.89 ± 9.8 years old. The majority of the study participants were male (57.7%), Malay (83.8%), Muslims (83.8%), singles (69%), and employed (75.8%), with about 83 (29.9%) of the respondents were smokers. The prevalence of e-cigarettes smokers was found to be only 1.4% (n = 4). About one-third of the respondents (n = 72, 26%) have tried e-cigarette before. Job status was significantly associated with smoking e-cigarette among the population (P = 0.02). Main factors for a person to start e-cigarette smoking were curiosity (37.5%) and cheaper price (40.8%). Majority of respondents agreed that e-cigarette would not affect health as normal cigarette, and that variety of flavors contribute to better enjoyment (51.6% and 66.7%, respectively).

Conclusion:

The results of the current study demonstrate that the prevalence of e-cigarettes smoking and its popularity, familiarity, and knowledge are still insufficient among Kuantan population. Further studies should be done to tackle this problem before it getting worse.

KEY WORDS: Electronic-cigarette, experimentation, Malaysia, perception, prevalence

The use of tobacco plants by humans returns for about 18,000 years ago. Tobacco leaves have been used for practical and medicinal purposes.[1] Evidence from the early 20th century pointed to the possible correlation between human smoking habits and death rates from lung cancer.[2] Cigarette smoking is responsible for six of the eight leading causes of death globally.[3] It has been estimated that about 15.8% of deaths in men and 3.3% of deaths in women in Asia were attributable to cigarette smoking.[4,5] Cigarettes are responsible for one in every four deaths in the United States.[6] Currently, the smokers have global average of about 50% of the young men and 10% of the young women.[7] For these reasons, stakeholders and consumers have sought for innovative tobacco and nicotine products enabled consumers to have a choice of less risky alternatives to the conventional cigarettes.[8,9] Until 2004, a device termed by the World Health Organization[3] as electronic nicotine delivery systems or electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) was invented.[6] E-cigarette founded to mimic the appearance and feeling associated with the use of regular cigarette in addition to providing a smoke-free vapor.[10] In the US, e-cigarette has been licensed as a tobacco product rather than a therapeutic product.[11] E-cigarettes have increasingly gained popularity across the world.[12,13] Studies have shown that there is a high proportion of smokers who have tried e-cigarette during 6 months before quitting smoking.[14,15,16] Furthermore, about 16 million children aged 17 or under have easy access to e-cigarettes in the US.[17] Considering the global popularity of using e-cigarette as a smoking cessation aid, there is a justification in interest to collect more information about their use and experimentation to help in making informed decisions on its use within this context.[10,18,19] In addition to other several factors including increased awareness of health risks, restrictions on public smoking, and increased tax on cigarettes, e-cigarette contributed to the reduction of the proportion of smokers by 1.2% of the total number of adult smokers that estimated by 19% of the population in Japan.[20,21] Despite the doubtful advantages of e-cigarette, the overall impact on population health and their harm reduction is still unclear.[22] However, there are increasing concerns about the potential for e-cigarettes to act as a “gateway” to cigarette smoking.[23,24,25,26,27] Recently, published data from the Centers for Disease Control pointed to the increase in the number of calls to poison centers involving e-cigarette liquids containing nicotine. Furthermore, about half (51.1%) of the reported poison cases involved were young children under age of five.[28] Saffari et al. reported that a particular brand of e-cigarette contains more than ten times the level of carcinogens contained in one regular cigarette.[29] Although exposure to e-cigarette's aerosol results in biological effects, the direct long-term effects on human health and environment are currently unknown.[22,30] However, different harm effects including cancers and upper respiratory tract irritation,[31,32] mouth and throat irritation, cough, nausea, and vomiting, and major injuries and illness such as explosions and fires were reported.[27] In contrast, a “risk assessment” of e-cigarette use in print by a pro – e-cigarette advocacy group, concluded that “neither inhalational exposure to vapor from e-liquids nor cigarette smoke analysis posed a condition of ‘significant risk’ of harm to human health.”[33] Despite the second-hand smoke safety claims, e-cigarettes still emit troublesome levels of toxic metals such as chromium and nickel.[29] Unlike the US legislation, health officials around the world have reacted to e-cigarettes with more strict product regulations, in most cases without rigorous research to support their claims; it remains difficult for governments and health policy makers to enact evidence-based product restrictions and regulations.[34] Due to the uncertainty about the efficacy and safety of e-cigarettes for smoking cessation, studies including large, generalizable, and randomized controlled trials are encouraged. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have been carried out purposively to examine the factors associated with use of e-cigarettes among Malaysian populations. This study has been conducted to report the prevalence of current e-cigarette use and also aimed to identify the sociodemographic factors, the motivators, attitudes, and perception that are associated with e-cigarette use among adults in Malaysia.

Methodology

Study design, sampling, and settings

The study was conducted over 2 months from October 2013 to December 2013. It was a cross-sectional study using a new validated, self-administered questionnaire. The sampling frame was general public living in Kuantan, Pahang, Malaysia. Automated software program was used for sample size calculation. To minimize erroneous results and increase the study reliability, ~6% of the estimated sample was collected. The target sample size was thus calculated to be 400 members of the general population of Kuantan, Malaysia.

The initial draft of the study questionnaire was constructed and developed using information from other previous studies about e-cigarette smoking in particular and water-pipe smoking in general.[10,21,35] However, the final questionnaire was six pages in length and consisted of 55 items classified into the following areas:

The first part consisted of 22 items which covered the demographic characteristics of the participants (age, gender, educational qualification and employment status,…etc.,) and other issues related to using of e-cigarette. The last 13 items of this part aimed to identify the factors that might induce and motivate the participants to use e-cigarette. These questions were either multiple-choice or consisted of filling the blanks.

The second part of the survey consisted of 10 items exploring the participant's familiarity with e-cigarette. The first 7 items were constructed as a series of statements, and the participants were asked to indicate their agreement or disagreement using a 5-point Likert scale format (“likely,” “neutral,” and “unlikely”). The remaining questions (n = 3) were looking for the health effects, additive effects and nicotine contents of e-cigarette. These questions were dichotomous questions (yes/no).

The third part of the survey consisted of 10-items, which explored the perception of the participants toward e-cigarette. These questions also used a 3-point Likert scale.

Face and content validation of the survey questionnaire

The questionnaire was tested for its face and content validity. Comments from experts working in the area of nicotine studies from Kulliyyah of Pharmacy, International Islamic University Malaysia (IIUM), were sought. Their comments were taken into consideration in the final draft of the questionnaire. The first draft of the questionnaire has been constructed in English. A standard “forward-backward” procedure was used to translate the survey questionnaire into Malay. Before the survey, the questionnaire was piloted with a convenient sample of twenty residents who were excluded from the main study. The reliability of the questionnaire was assessed using Cronbach's coefficient alpha. The internal consistency for the overall instrument was 0.871.

Ethical approval and data analysis

The study protocol was approved by the Pharmacy Practice Department, Kulliyyah of Pharmacy, IIUM, Malaysia. Anonymity and confidentiality were ensured. Consent for participation was implied by the completion and return of the survey instrument.

All the data obtained from the questionnaire were entered into the SPSS version 17.0 software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for analysis. The mean (+ Standard deviation) was calculated for continuous variables such as age. The frequencies were measured for categorical variables. Any associations/differences between groups were examined by the Chi-square or Fisher exact tests as appropriate for categorical variables. Data, which emerged from domains using a Likert scale as a measurement, were analyzed statistically as nonparametric data.

Results

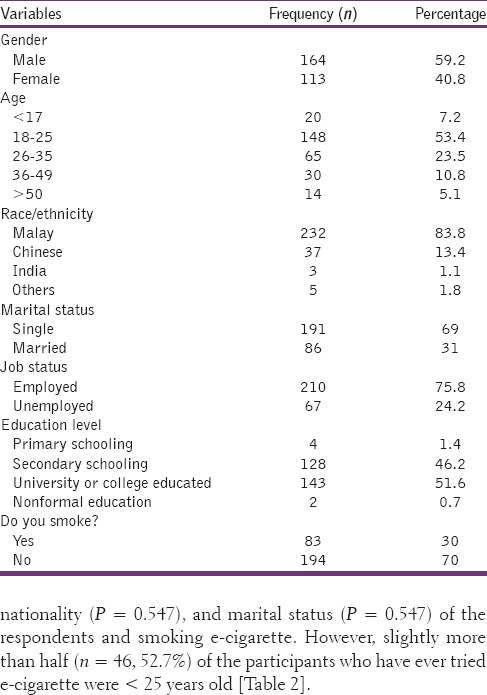

Over 2 months of the study period, a total of 400 self-completed surveys were distributed among general public in Kuantan in public places such as mosques and shopping malls, with 282 completed surveys (response rate was 70.5%) and five incomplete surveys. The total number of the usable responses was 277 (69.2%). The study findings revealed that the majority of the respondents were male (57.7%), Malay (83.8%), Muslims (83.8%), singles (69%), and employed (75.8%). The mean age of participants was 26.9 ± 9.8 years. Slightly more than half of the participants (n = 143, 51.6%) are currently studying or have graduated from university or college [Table 1].

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants (n=277)

Prevalence and factors contribute to electronic cigarette smoking among general public

The current study assessed the general public views and familiarity toward e-cigarettes among Kuantan population. The prevalence of smoking habit among study subjects was (n = 83, 29.9%). However, 2.8% of the respondents smoke either e-cigarette only or regular cigarettes. The vast majority of respondents were current nonsmokers (n = 194, 70%). In response to the question whether the respondents have tried e-cigarette previously, about one-third of the respondents (n = 72, 26%) have stated that they had used e-cigarette before.

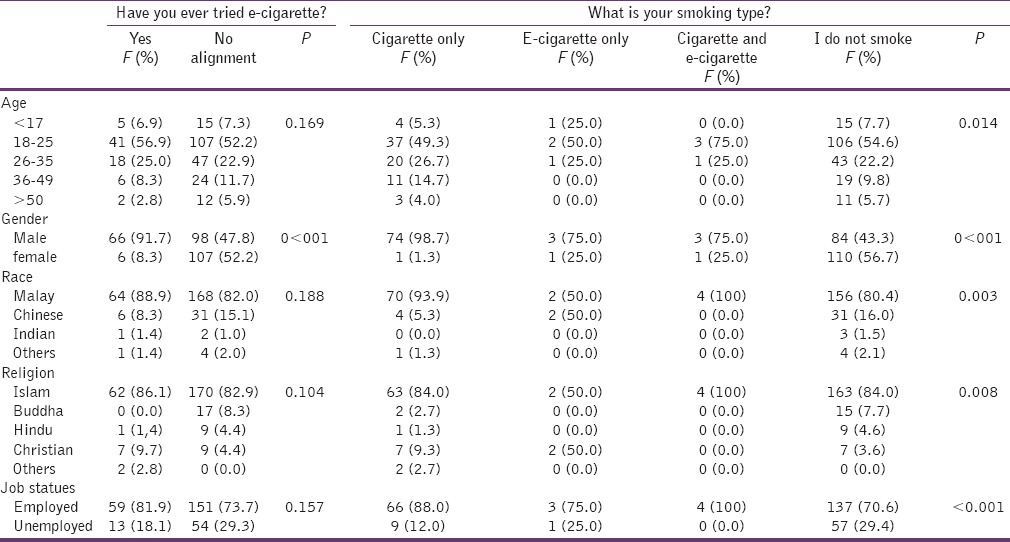

The study results showed that there is a very strong statistical significance association (P < 0.001) between gender of respondents and experience using of e-cigarettes. The vast majority of e-cigarette experimenters were male (n = 66, 91.7%). There is a no statistical significant relationship between the race (P = 0.188), age (P = 0.169), job status (P = 0.157), religion (P = 0.104), nationality (P = 0.547), and marital status (P = 0.547) of the respondents and smoking e-cigarette. However, slightly more than half (n = 46, 52.7%) of the participants who have ever tried e-cigarette were < 25 years old [Table 2].

Table 2.

Respondents’ sociodemographic data with regard to the smoking type and experience of e-cigarette (n=277)

Aiming to identify the most common motivator to trying e-cigarette among study participants, the study results showed that friends of the participants are the major (n = 48, 17.3%) motivators to try e-cigarette. With regard to the current e-cigarette users and despite the low prevalence of e-cigarette users among the study population, the majority of currently e-cigarette users prefer to use e-cigarette at restaurants or cafes (n = 6, 75%). About 37.5% of them (n = 3) usually share e-cigarette with others. One-fourth (n = 2, 25%) of the subjects who are currently users often smoke e-cigarette weekly while the majority (n = 6, 75%) smoke e-cigarette on a daily basis. The vast majority of current e-cigarette smokers (n = 5, 62.5%) claimed that e-cigarette helps them to relieve tension and stress. Surprisingly, almost all participants (n = 7, 87.5%) do not smoke e-cigarette for pleasure and happiness. However, 37.5% of the current smokers are motivated to use e-cigarette because of curiosity.

Desiring to explore the study population familiarity with e-cigarette, all the participants were asked to answer the items of this domain. Despite the low prevalence of e-cigarette usage among the study population, the vast majority of the subjects (n = 216, 78%) stated that they are familiar with e-cigarette. However, about one-quarter of them (n = 72, 26%) have tried e-cigarette at least once in their life span. There is a strong statistically significant association in response to the previous question which about familiarity and trying e-cigarette (P = 0.001). There is a strong statistical association of being familiar and experimentation of e-cigarette (P = 0.004). However, about one-third of the current smokers (n = 74, 34.3%) stated that they are familiar with e-cigarette. In addition, about one-third of those who smoke regular cigarette only (n = 65, 31.1%) reported that they are familiar with e-cigarette. There is no statistical association between familiarity with e-cigarette and age (P = 0.142), religion (P = 0.010), job status (P = 0.090), and marital status (P = 0.090). The vast majority of the respondents who admitted their familiarity with the e-cigarettes, friends, and media (e.g., TV. and internet…etc.,) were the main source of knowledge (n = 187, 86.6%).

Aiming to assess the susceptibility of study population to e-cigarette in future, study participants were asked the following question: “In future, do you intend to use e-cigarette?” The majority (n = 225, 81.2%) of the respondents were unlikely unsusceptible to use e-cigarettes in the future.

With regard to the previous experience of using e-cigarette, statistically significant difference between prior using and susceptibility to e-cigarette in future has been observed (P = 0.001). The susceptibility to e-cigarette in the future was very low among those who never tried e-cigarette in the past (n = 175, 85.4%), where only 2 (1%) of them were answered in affirmative to the asked question.

Familiarity about electronic cigarettes

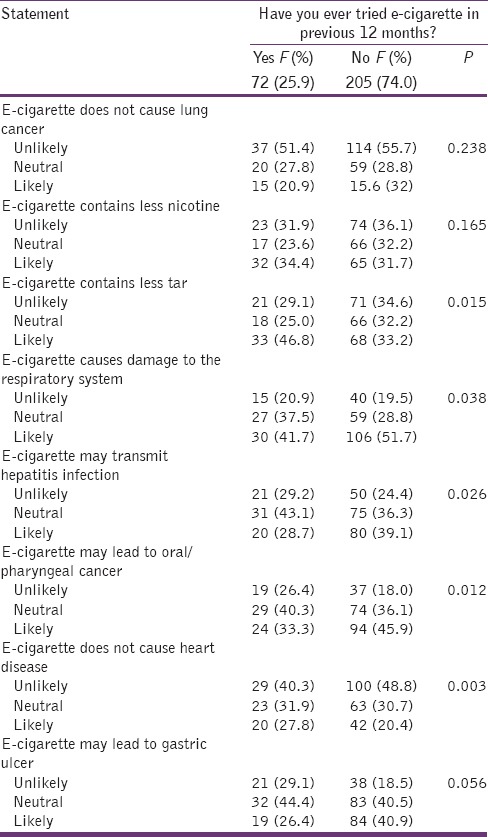

Slightly more than half of the respondents (n = 151, 54.5%) believed that e-cigarette does not cause lung cancer while some (n = 136, 49.1%) claimed that e-cigarette causes damage to the respiratory system. High proportional of respondents (n = 100, 36.1%) thinks that e-cigarette may transmit hepatitis infection. About one-third (n = 103, 37.1%) of participants claimed that e-cigarette may cause gastritis. Slightly less than half of respondents (n = 129, 46.6%) unlikely think that e-cigarette cause heart disease. When asked about the link between e-cigarette and the development of throat or pharyngeal cancer, 108 (42.6%) agreed with this while 103 (37%) were not sure.

About one-fourth of subjects (n = 72, 26%) thought that e-cigarette is more harmful than normal cigarettes while others (n = 124, 44.8%) thought that e-cigarette has the same harmful effects of normal cigarettes. Regarding nicotine contents in e-cigarette in comparison with normal cigarettes, about half of respondents (n = 129, 46.6%) claimed that normal cigarettes contain nicotine more than e-cigarettes. Table 3 shows the knowledge/familiarity status and experience of using e-cigarette among the study subjects.

Table 3.

Familiarity with e-cigarette among those who tried e-cigarette (n=277)

Perceptions of electronic cigarette smoking

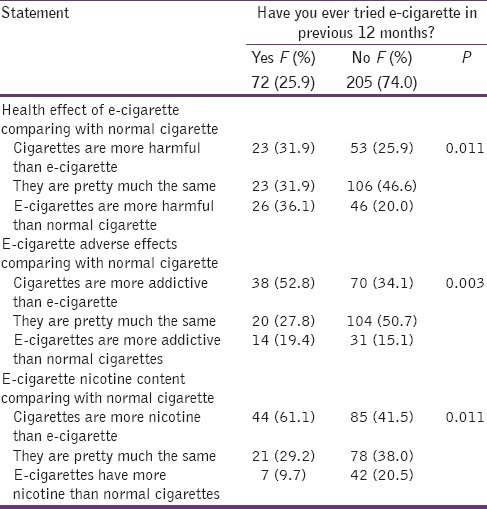

About more than one-third (n = 103, 37.2%) of subjects disagreed that e-cigarette is acceptable by the society compared to normal cigarettes, and with the same percentage of respondents were neutral. The study findings showed that there is no statistically significant relationship between trying and seeing of e-cigarettes socially acceptable (P = 0.115). High percentage of respondents (n = 113, 40.8%) agreed that e-cigarette is more economical compared to normal cigarettes. Statistically significant relation between trying and seeing e-cigarette is more economical than normal cigarette has been observed (P < 0.001). However, about 50% of the current e-cigarette users stated that they spent < 30 Malaysian Ringgits (how much in US$??) per week on e-cigarettes, and only about one-quarter (25%) of them spent more than 100 Malaysian Ringgits (1USD = 3.15 RM).

About half of respondents (n = 38, 52.8%) who tried e-cigarette previously agreed that e-cigarette is more economical than regular cigarette. The study results showed that there is a significant association between trying and seeing e-cigarette as more enjoyable than normal cigarette. As a result of a variety of flavors, high percentage of participants who tried e-cigarette in the past (n = 48, 66.7%) believed that e-cigarette is more pleasant than regular ones. Only minority of the respondents (n = 42, 15.2%) agreed that e-cigarette relieved stress and tension. There is a statistically significant association between trying and perceiving e-cigarette smoking to relieve stress and tension (P = 0.028). Only few numbers of respondents (n = 13, 18.1%) who tried e-cigarette in the past agree in the affirmative. Slightly more than one-third of respondents who have tried e-cigarette (n = 26, 36.1%) claimed that e-cigarette is more harmful to health than normal cigarette. In addition, there is no significant difference between those who have experienced e-cigarette and the belief that e-cigarette will not affect health compared to normal cigarette (P = 0.153).

A relative statistically significant relationship between the experience of e-cigarette and the concept that e-cigarette is safe compared to conventional cigarette (P = 0.037) was demonstrated. Slightly less than half of respondents (n = 92, 44.9%) who never tried e-cigarette disagreed with the statement that e-cigarette is safer than normal cigarette. About half of respondents (n = 134, 48.4%) agreed that e-cigarette shows innovation of creative people in daily life. However, more than half of those who tried e-cigarette in the past (n = 45, 62.5%) agreed with the previously mentioned statement. The study results showed that there is a relatively statistically significant association between trying e-cigarette and speculating that e-cigarette usage will be popular in Malaysia (P = 0.044).

Regarding the safety of e-cigarette in comparison to normal cigarettes, about one-fifth of the whole study respondents (n = 60, 21.7%) agreed that e-cigarette is safer. Surprisingly, the majority of respondents (n = 174, 62.8%) believed that their parents would not allow them to use of e-cigarette at home, unlike regular cigarette. However, majority of the respondents who have tried e-cigarette (40%) were neutral on whether the e-cigarette will gain more popularity among Malaysian population while only (27.1%) of them agreed with that statement. In addition, the vast majority of respondents (n = 225, 81.2%) claimed that they will not use e-cigarette in the future. Table 4 shows respondents’ perception toward e-cigarettes.

Table 4.

Respondents’ perception toward e-cigarettes (n=277)

Discussion

E-cigarettes were developed to curtail the harmful effects of conventional cigarettes and on the other hand, may serve as a trigger for young people. Results of the current work showed that the prevalence of smoking among Malaysian study population was found to be 29.9%, and the majority were young adult men with an overall prevalence of 23.1% increase of what was reported in the tobacco adult survey in 2011.[36] The proportion of smokers reporting that they have tried e-cigarettes was found to be 26% comparably higher than those reported in Great Britain (15%), Australia (20%), and China (2%). Study findings indicated that there was a rising in the level of the awareness among study population (78%) comparing with the findings that reported by Gravely et al., which is only 19%.[37] These findings are high compared with other countries in the Asian Pacific region such as Republic of Korea (2010, 79%), Australia (2013, 66%), and China (2009, 31%).[37] These may be attributed to the massive increase in the e-cigarette trading among Malaysian population. This reflected increase in e-cigarette awareness in Malaysia may serve as an initiation path to smoking as proposed in other studies.[14,24,25,26] The study results showed that there is no association between sociodemographic characteristics of the participants and trial of e-cigarette. The findings revealed a strong association between e-cigarette and gender (P < 0.001), with more than half of the study population, were males. Gender differences in terms of usage and trial were observed, with males are more likely to have tried or be using cigarettes than females. This finding is consistent with the data reported previously from Poland.[35]

Concerning questions about psychosocial factors that may motivate an individual to try e-cigarette smoking, our findings revealed that 17% of the study participants were motivated to try by their friends and about one-third of the study participants reported that they were motivated by curiosity while majority (n = 6, 75%) of cigarette smokers were motivated by family members. This is in agreement with the previous findings that individuals who had a parent or partner who smoked were more likely to use e-cigarettes and other tobacco products than those with no smoking person in their family or a close relationship.[38] In addition, it was revealed from our study that daily use of e-cigarette relieves feelings of stress and tension among the respondents. This may be attributed to the rewarding effect of nicotine from the e-cigarette. This is in contrary to previous work reported that tobacco e-cigarette use does not alleviate stress but actually increases its need to use cigarettes to relieve feeling of stress.[2]

In our study, the vast majority of respondents (78%) reported that they are familiar with e-cigarette through friends and social media (86.6%). These results were comparably higher than the US reported data on adult population that awareness rate was 57.9% and only 6.2% of them have had ever-use of e-cigarette.[39] These results suggest the possibility of harnessing this media in promotional activities. In order to reduce tobacco smoking in general, and stop using the electronic cigarette. The current finding showed a significant difference between prior usage and susceptibility to e-cigarette in future (P = 0.001). In a recent study, Kim et al. reported that 66% of the respondents opinionated that e-cigarette promotions and advertising adverts through television and radio made them likely to try an e-cigarette in future.[39]

In our study, majority of the respondents believed that e-cigarette causes lung cancer (54.5%) and damages respiratory system (49.1%). Although the long term effects of using e-cigarette is not yet well proven, the majority of the study respondents believed that e-cigarette vaping causes lung cancer and damages respiratory system (54.4% and 49.1 %, respectively). Further rigorous and well-designed studies are needed to elucidate the potential health consequences of e-cigarettes.

Most of the respondents cited economic advantage of e-cigarette over conventional cigarette as a perceived benefits motivated them to try it for the 1st time (P < 0.001) and more societal acceptance as another perceived benefit (P = 0.115), similar finding were reported by Etter et al.[8] This may be related to common advertisements for e-cigarette that claims they are more cost-effective, less health risks, less prohibitions, and more socially acceptable compared with traditional cigarettes.[6] In addition, general public always are curious to test a new technology and the emergence of e-cigarette technology phenomenon took tobacco control community by surprise. It is notable that Malaysian clients showed their curiosity to encourage e-cigarette as an innovation of creativity in modern life (P = 0.003).

In terms of safety, only 22% of the respondents considered that e-cigarette is safer than conventional cigarettes, whereas nearly 46% disagreed that are much safer than normal cigarette. However, e-cigarette has been penetrating market rapidly despite many unanswered questions about their safety, and many of the findings from the studies assessing the various e-cigarette products have not given enough evidence to support the claims that all these products were safe and effective as nicotine delivery devices.[10,40,41] On the other hand, more than 80% of the study clients claimed their strong aversion to use e-cigarettes in future.

Although study users’ comments were mixed, many were concerned about the safety and health effects of e-cigarettes, and this question remains unanswered and this calls for more studies to investigate these aspects. E-cigarette is currently manufactured by many small companies and questioned whether these manufacturers maintain same rigorous standards as apply to all pharmaceutical products. The legal status is unclear in many countries and difficult to quantify the balance between these complex regulations and protecting consumers. Tobacco smoking itself has given enormous burden of diseases and deaths; therefore, there is an urgent need for research to produce evidence on the safety of e-cigarettes and its impact on public health.

Limitations and strengths

Needless to say, our study has important methodological limitations resulting from the fact that difficulty of sampling a large population size due to technical and logistical concerns. The present study is among the first to investigate the e-cigarette social profile in Kuantan, Malaysia; however, these findings should be interpreted with some caution.

Therefore, the findings may not be extrapolated to the other general public in other states in the country. However, the study findings do provide insight into aspects that should be further investigated as a part of a larger study in the future. Our team plans to extend the current findings to include a larger sample size that represents different geographical areas of Malaysia. Thus, it will represent the Malaysia population in a well-formed design. Finally, our results alert the health care providers and policy makers to be aware of the e-cigarette problem within the Malaysian society with tailoring appropriate intervention programs at the national level.

Conclusion

The current study has generated important data about the characteristics and attitudes of general public in Malaysia regarding e-cigarette use. Notably, e-cigarette awareness and use were evident among our sample population. Ongoing surveillance and monitoring of awareness and use of e-cigarettes in Malaysia could help inform tobacco control policies and public health interventions, especially educational programs among vulnerable teenagers. E-cigarette consciousness and use were evident in our sample; however, there is a need to correct misconception and myths related to using e-cigarette among Malaysian general population. Continuing shadowing and observing of awareness and use of e-cigarettes in Malaysia could help inform tobacco control policies and public health interventions. Future studies should be carried out to observe the use of e-cigarettes among current smokers and curiosity among nonsmokers and reverting former smokers.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Gately I. New York: Grove Press; 2007. Tobacco: A Cultural History of How an Exotic Plant Seduced Civilization. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parrott AC. Does cigarette smoking cause stress? Am Psychol. 1999;54:817–20. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.10.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. World Health Organization. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2008: The MPOWER Package; p. 342. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zheng W, McLerran DF, Rolland BA, Fu Z, Boffetta P, He J, et al. Burden of total and cause-specific mortality related to tobacco smoking among adults aged≥45 years in Asia: A pooled analysis of 21 cohorts. PLoS Med. 2014;11:e1001631. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.London: RCP; 2007. Royal College of Physicians. Harm reduction in nicotine addiction: helping people who can’t quit. A report by the Tobacco Advisory Group of the Royal College of Physicians. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Health UDo, Services H. The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, Coordinating Centre for Health Promotion, National Centre for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2006. :709. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jha P, Peto R. Global effects of smoking, of quitting, and of taxing tobacco. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:60–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1308383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Etter JF, Bullen C, Flouris AD, Laugesen M, Eissenberg T. Electronic nicotine delivery systems: A research agenda. Tob Control. 2011;20:243–8. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.042168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laugesen M. Ruyan E-cigarette Bench-top Tests. Poster presented at the Conference of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco Dublin; 27.30, April 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bullen C, McRobbie H, Thornley S, Glover M, Lin R, Laugesen M. Effect of an electronic nicotine delivery device (e cigarette) on desire to smoke and withdrawal, user preferences and nicotine delivery: Randomised cross-over trial. Tob Control. 2010;19:98–103. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.031567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riker CA, Lee K, Darville A, Hahn EJ. E-cigarettes: Promise or peril? Nurs Clin North Am. 2012;47:159–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zyoud SH, Al-Jabi SW, Sweileh WM. Bibliometric analysis of scientific publications on waterpipe (narghile, shisha, hookah) tobacco smoking during the period 2003-2012. Tob Induc Dis. 2014;12:7. doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-12-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamin CK, Bitton A, Bates DW. E-cigarettes: A rapidly growing Internet phenomenon. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:607–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-9-201011020-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pepper JK, Ribisl KM, Emery SL, Brewer NT. Reasons for starting and stopping electronic cigarette use. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:10345–61. doi: 10.3390/ijerph111010345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ebbert JO, Agunwamba AA, Rutten LJ. Counseling patients on the use of electronic cigarettes. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:128–34. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Regan AK, Promoff G, Dube SR, Arrazola R. Electronic nicotine delivery systems: Adult use and awareness of the ‘e-cigarette’ in the USA. Tob Control. 2013;22:19–23. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bunnell RE, Agaku IT, Arrazola RA, Apelberg BJ, Caraballo RS, Corey CG, et al. Intentions to smoke cigarettes among never-smoking US middle and high school electronic cigarette users: National Youth Tobacco Survey, 2011-2013. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17:228–35. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.West R, Brown J. The smoking toolkit study: A brief summary. Smoking in England. [Last accessed on 2016 Feb 09]. Available from: http://www.smokinginenglandinfo/downloadfile/?type=sts--documents & src=18 .

- 19.Brown J, Beard E, Kotz D, Michie S, West R. Real-world effectiveness of e-cigarettes when used to aid smoking cessation: A cross-sectional population study. Addiction. 2014;109:1531–40. doi: 10.1111/add.12623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Polosa R, Rodu B, Caponnetto P, Maglia M, Raciti C. A fresh look at tobacco harm reduction: The case for the electronic cigarette. Harm Reduct J. 2013;10:19. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-10-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Polosa R, Rodu B, Caponnetto P, Maglia M, Raciti C. A fresh look at tobacco harm reduction: The case for the electronic cigarette. Harm Reduct J. 2013;10:19. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-10-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drummond MB, Upson D. Electronic cigarettes. Potential harms and benefits. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11:236–42. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201311-391FR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grana R, Benowitz N, Glantz SA. E-cigarettes: A scientific review. Circulation. 2014;129:1972–86. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.007667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grana RA. Electronic cigarettes: A new nicotine gateway? J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:135–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pepper JK, Reiter PL, McRee AL, Cameron LD, Gilkey MB, Brewer NT. Adolescent males’ awareness of and willingness to try electronic cigarettes. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:144–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schober W, Szendrei K, Matzen W, Osiander-Fuchs H, Heitmann D, Schettgen T, et al. Use of electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) impairs indoor air quality and increases FeNO levels of e-cigarette consumers. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2014;217:628–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen IL. FDA summary of adverse events on electronic cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15:615–6. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chatham-Stephens K, Law R, Taylor E, Melstrom P, Bunnell R, Wang B, et al. Notes from the field: Calls to poison centers for exposures to electronic cigarettes – United States, September 2010-February 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:292–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saffari A, Daher N, Ruprecht A, De Marco C, Pozzi P, Boffi R, et al. Particulate metals and organic compounds from electronic and tobacco-containing cigarettes: Comparison of emission rates and secondhand exposure. Environ Sci Process Impacts. 2014;16:2259–67. doi: 10.1039/c4em00415a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farsalinos KE, Polosa R. Safety evaluation and risk assessment of electronic cigarettes as tobacco cigarette substitutes: A systematic review. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2014;5:67–86. doi: 10.1177/2042098614524430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laino T, Tuma C, Moor P, Martin E, Stolz S, Curioni A. Mechanisms of propylene glycol and triacetin pyrolysis. J Phys Chem A. 2012;116:4602–9. doi: 10.1021/jp300997d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henderson TR, Clark CR, Marshall TC, Hanson RL, Hobbs CH. Heat degradation studies of solar heat transfer fluids. Sol Energy. 1981;27:121–8. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McAuley TR, Hopke PK, Zhao J, Babaian S. Comparison of the effects of e-cigarette vapor and cigarette smoke on indoor air quality. Inhal Toxicol. 2012;24:850–7. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2012.724728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McNeill A, Etter JF, Farsalinos K, Hajek P, le Houezec J, McRobbie H. A critique of a World Health Organization-commissioned report and associated paper on electronic cigarettes. Addiction. 2014;109:2128–34. doi: 10.1111/add.12730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goniewicz ML, Zielinska-Danch W. Electronic cigarette use among teenagers and young adults in Poland. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e879–85. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Omar A, Yusoff MF, Hiong TG, Aris T, Morton J, Pujari S. Methodology of Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS), Malaysia, 2011. Int J Public Health Res. 2013;3:297–305. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gravely S, Fong GT, Cummings KM, Yan M, Quah AC, Borland R, et al. Awareness, trial, and current use of electronic cigarettes in 10 countries: Findings from the ITC project. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:11691–704. doi: 10.3390/ijerph111111691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goebel LJ, Crespo RD, Abraham RT, Masho SW, Glover ED. Correlates of youth smokeless tobacco use. Nicotine Tob Res. 2000;2:319–25. doi: 10.1080/713688153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim AE, Lee YO, Shafer P, Nonnemaker J, Makarenko O. Adult smokers’ receptivity to a television advert for electronic nicotine delivery systems. Tob Control. 2015;24:132–5. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pearson JL, Richardson A, Niaura RS, Vallone DM, Abrams DB. E-cigarette awareness, use, and harm perceptions in US adults. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:1758–66. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Westenberger B. St. Louis, MO: Department of Health and Human Services. Food and Drug Administration, Centre for Drug Evaluation and Research, Division of Pharmaceutical Analysis; [Last accessed on 2016 Feb12]. Evaluation of e-Cigarettes. Available from: http://www.truthaboutecigscom/science/2pdf . [Google Scholar]