Abstract

Background

Although studies show that genomics and environmental stressors affect blood pressure, few studies have examined their combined effects, especially in African Americans.

Objective

We present the recruitment methods and psychological measures of the Intergenerational Impact of Genetic and Psychological Factors on Blood Pressure (InterGEN) study, which seeks to investigate the individual and combined effects of genetic (G) and environmental (E) (psychological) stressors on blood pressure in African American, mother-child dyads. Genetic methods are presented elsewhere, but here we present the recruitment methods, psychological measures, and analysis plan for these environmental stressors.

Methods

This longitudinal study will enroll 250 mother-child dyads (N = 500). Study participation is restricted to women who: (a) are ≥ 21 years of age; (b) self-identify as African American or Black; (c) speak English; (d) do not have an identified mental illness or cognitive impairment; and (e) have a biological child between three to five years old. The primary environmental stressors assessed are parenting stress, perceived racism and discrimination, and maternal mental health. Covariates include age, cigarette smoking (for mothers), and gender (for children). The study outcome variables are systolic and diastolic blood pressure.

Analysis

The main analytic outcome is genetic-by-environment interaction analyses (G × E), however, main effects (G) and (E) will be individually assessed first. Genetic (G) and interaction analyses (G × E) are described in a companion paper and will include laboratory procedures. Statistical modeling of environmental stressors on blood pressure will be done using descriptive statistics and generalized estimating equation (GEE) models.

Implications

The methodology presented here includes the study rationale, community engagement and recruitment protocol, psychological variable measurement, and analysis plan for assessing the association of environmental stressors and blood pressure. This study may provide the foundation for other studies and development of interventions to reduce the risk for hypertension, and to propose targeted health promotion programs for this high-risk population.

Keywords: African Americans, blood pressure, gene-environment interaction, generalized estimating equations, parenting, racism, social discrimination

Hypertension is the most common risk factor for cardiovascular disease in the United States (Go et al., 2014), and African American adults bear a disproportionately high prevalence (42.1%) compared to Whites (28.0%), Hispanics (26.0%), and Asians (24.7%) (Nwankwo, Yoon, Burt, & Gu, 2013). Rates of hypertension have risen significantly among eight to 17-year-olds in the U.S. (Muntner, He, Cutler, Wildman, & Whelton, 2004), and signs of atherosclerosis can be identified as early as three years old which, if left untreated, lead to irreversible coronary heart disease early in adulthood (Wung, Hickey, Taylor, & Gallek, 2013).

Previous studies have attempted to explain the phenomenon of hypertension among African Americans by investigating the independent effects of social determinants, including risk factors such as physical activity, salt sensitivity, body mass index, genetic predisposition, and psychological stressors such as racism (Taylor, Sun, Chu, Mosley, & Kardis, 2008; Taylor, Maddox, & Wu, 2009); however, these and other traditional risk factors are not sufficient to illuminate the complex etiology of hypertension in this population (Hansen, Gunn, & Kaelber, 2007; Roger et al., 2011; Taylor et al., 2008). Demographic variables, such as socioeconomic status and gender, may influence blood pressure (Cundiff, Uchino, Smith, & Birmingham, 2015), however, most Americans (86%) with uncontrolled high blood pressure have some type of health insurance and a regular provider (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2011), demonstrating that improvements in adherence to treatment and an individualized approach may be necessary.

Experiences of racial discrimination also have been associated with increased blood pressure in adults (Roger et al., 2011) and poor health in children (Sanders-Phillips, Settles-Reaves, Walker, & Brownlow, 2009). Mothers who have vicariously witnessed racial discrimination against their children report this experience as being particularly distressing (Nuru-Jeter et al., 2009). Studies have varied in measurement of discrimination, and most have focused on adults (Dolezsar, McGrath, Herzig, & Miller, 2014; Taylor et al., 2012), signaling the need for more research on effects of discrimination on mothers and their children.

Maternal depression is a significant risk factor for poor outcomes, including blood pressure, in young children (Artinian, Washington, Flack, Hockman, & Jen, 2006) as it affects a mother's pattern of interaction with her children during early critical periods of development (Stein et al., 2014). This lack of social-emotional connection between a mother and her infant early in life can predict stress sensitivity in infants (Hane & Fox, 2006; Pederson, Gleason, Moran, & Bento, 1998) and may be associated with increases in blood pressure. Similarly, parenting stress has been significantly associated with high blood pressure in mothers (Taylor, Washington, Artinian, & Lichtenberg, 2007).

Genetic factors are also associated with blood pressure risk. Large cohort studies have identified single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) located on chromosome 2 that are associated with hypertension susceptibility in African Americans (Barkley et al., 2004; Taylor et al., 2009), but additional genes are probably involved and have not yet been studied in African American children. Epigenetic factors (DNA modifications that turn genes “on” or “off,” but do not change the DNA sequence [Berger, Kouzarides, Shiekhattar, & Shilatifard, 2009]) may also play a role, as environmental exposures cause DNA methylation and varying patterns of gene expression and disease (Fraga et al., 2005). Some epigenetic modifications can be inherited across generations (i.e., parent-child transmission), and early environmental exposures, such as psychological stressors, abuse, and socioeconomic status in pregnancy, can change DNA methylation patterns in the fetus (Heijmans et al., 2008; Lam et al., 2012).

Although the individual effects of both genomic and environmental stressors on the development of hypertension have been studied, few have focused on mothers and their children, and there is a paucity of research on the interaction (nonadditive synergistic effects) of genetic and environmental variables on increases in blood pressure. Further, to fully understand and interpret interaction effects, it is important to have a clear understanding of the variance contributed by main effects (in this case, environmental exposures). The use of multiple sources of information, including individual-level biological data (e.g., genetic and epigenetic factors, blood pressure), as well as demographic and psychological data, gathered via interview is an innovative approach to assessing the multitude of factors that impact maternal and child health. Results from this investigation will provide the platform for the critically important development of theoretical and empirically informed strategies to reduce health disparities in hypertension among African American mothers and their children.

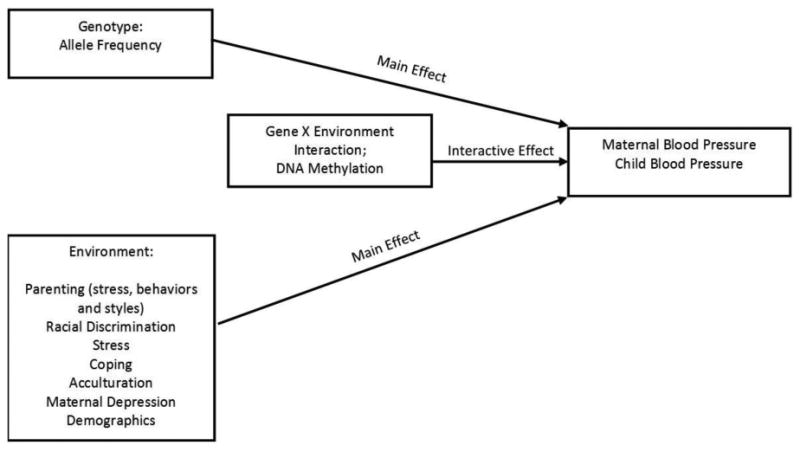

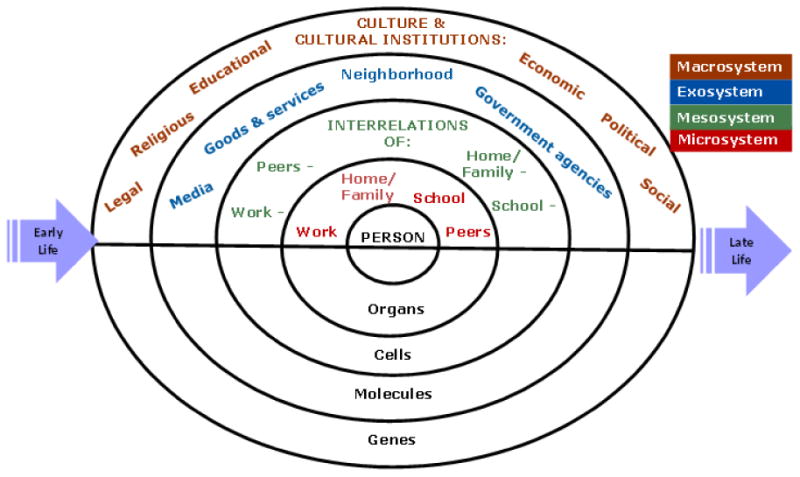

The theoretical framework for this study, shown in Figure 1, is informed by Bronfenbrenner's (2005) bioecological theory of human development, which states that child development results from an interaction between the individual and his or her environment or context. Bronfenbrenner's model incorporates transactions between systems (micro-, meso-, exo-, and macro-systems), including proximal processes such as parenting and environmental stressors, distal processes such as economic systems, and changes in conditions and the individual's life over time (chronosystem). An adaptation of this model (Figure 2) has been developed which incorporates biological changes to the individual over time, and includes genes (Glass & McAtee, 2006; Tebes, 2016). This expanded model provides a framework to examine proximal processes, such as environmental stressors, which co-occur with changes to genes. These stressors may directly influence child outcomes as a result of insults to the epigenome. In addition, we apply the concept of resilience to the examination of cardiovascular outcomes. Resilience is a phenomenon often studied in child development and psychology in which children succeed despite adversity, such as poverty, discrimination, and living with a mother experiencing depression. We contribute to the fourth wave of resilience research (Wright, Masten, & Narayan, 2013) by extending Bronfenbrenner's theory to propose a model where genetic and environmental factors at multiple levels of analysis (i.e., parental coping and parenting styles) interact to shape cardiovascular outcomes. Our study is especially unique as it allows for longitudinal study of psychological stressors and, therefore, addresses the chronosystem that is often understudied in theoretical contexts using this model (Tudge, Mokrova, Hatfield, & Karnik, 2009). This gene-environment model is a novel approach that advances both nursing science and psychology.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework for the Intergenerational Impact of Genetic and Psychological Factors on Blood Pressure Study (InterGEN). This framework is informed by Bronfenbrenner's bioecological theory of human development, which states that child development results from an interaction between the individual and his or her environment or context (Bronfenbrenner, 2005). This theory consists of four main elements: (a) the person's biology, genomics, and characteristics, (b) the reciprocal interactions between the child and the persons and objects in his or her immediate environment, (c) the environment, which may have an influence on the individual; and (d) how outcomes of interest remain stable or change over time (Tudge, Mokrova, Hatfield, & Karnik, 2009). Young children develop in an environment of relationships, and the maternal caregiver is most often the primary relationship. Mothers' experience of racial discrimination, depression, and parenting behaviors are important psychological environmental factors that impact the experiences and health of young children.

Figure 2.

An embodied social ecological model for understanding contexts for human behavior. From Tebes, J. K. (2016). Community psychology for this century: Perspectives on the future of the field from the generations after Swampscott.American Journal of Community Psychology.Society for Community Research and Action (SCRA) published by Wiley; reprinted with permission.

Therefore, in this paper we present the subaims [psychological environmental factors (E)] of the larger G×E study, as the methods for the genetic (G) portion of the study are described elsewhere (Taylor, Wright, Crusto, & Sun, 2016). The subaims focusing on the psychological environmental factors are: (a) examine the effects of mother's perceived discrimination on their and their child's BP over a two-year period; (b) examine the effects of mother's mental health (depressive symptoms) on their and their child's BP over a two-year period; and (c) examine the effects of mother's parenting behavior (stress and behavior) ontheir and their child's BP over a two-year period. We hypothesize that exposure to psychological, environmental risks is associated with increased blood pressure readings among both African American mothers and children over time. This research is innovative as we are including children as young as three years of age, and those who are undiagnosed—which will allow for identification of risk over time. The psychological measures of stress in this study may change over time and directly influence blood pressure, therefore, a longitudinal study design is ideal to examine these issues. This paper may serve as a guide to other researchers interested in replicating or conducting multidisciplinary work on African American mother/child dyads that examine the interactive effects of psychological and genetic/genomic factors contributing to hypertension risk in this population.

Methods

Design

InterGEN is a multidisciplinary, ongoing, longitudinal study based in Southwest and Central Connecticut. The study partners with 12 Early Care and Education (ECE) Centers which provide preschool education for qualifying low-income children in ethically and racially diverse communities. The majority of study participants are recruited via ECEs, and remaining participants are recruited from community events with similar target populations. ECEs are provided with study materials such as brochures, business cards, and flyers for distribution to potential families.

Procedures

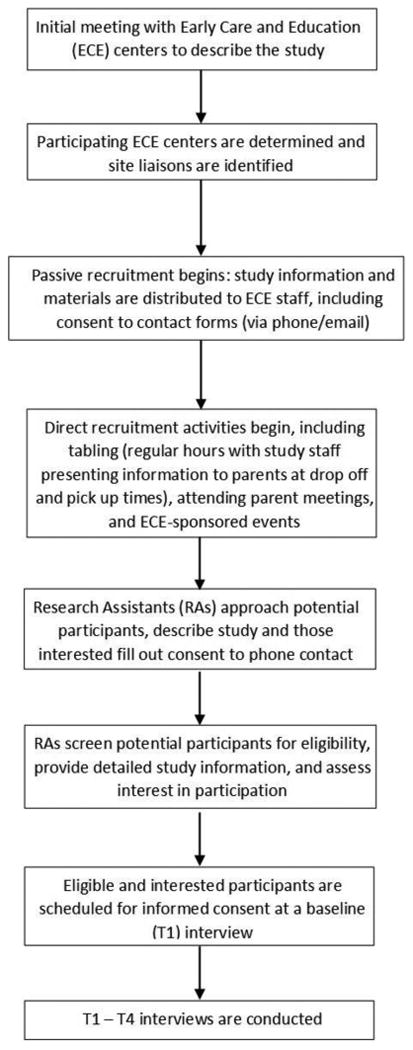

Recruitment for the study began in April 2015, with an enrollment goal of 250 mother-child dyads, and the community engagement and recruitment protocol is summarized in Figure 3. Briefly, women are approached by study staff in partnering ECEs, informed of the study aims and procedures, and consent to be contacted for screening. Telephone screening is then done to ensure eligibility criteria are met, and then an appointment is scheduled for the first interview. Families will be interviewed at four time points (T) in the study: (T1–enrollment, T2–six months postenrollment, T3–12 months postenrollment, and T4–18 months postenrollment). Written, informed consent is obtained at T1, and all study procedures have been approved by Yale University's Institutional Review Board. Clinical data are measured at each interview (T1-T4), and DNA is collected at T1 only. Demographic information and psychological data are collected using Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Interviewing (ACASI) (T1-T4). Eligibility for participation in the study is restricted to women who: (a) are ≥ 21 years old; (b) identify as African American or Black (via self-report); (c) speak English; (d) do not have a psychiatric or cognitive disorder which may limit accuracy of reporting of study data; and (e) have a biological child three to five years old.

Figure 3.

InterGEN community engagement and recruitment protocol.

Primary Outcome (Dependent) Variables

The primary study outcome (dependent) variables are systolic and diastolic blood pressure. At each study visit (T1-T4), blood pressure measurements are obtained from the participating mother and her child by trained data collectors following the study protocol and according to Joint National Committee (JNC)-7 guidelines (Chobanian et al., 2003; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents, 2004). Before the T1 interview, mothers are sent a letter reminding them that blood pressure will be measured three times during the interview. The mother is informed that this is resting measurement, and that the child should not be too active for about five minutes before his or her blood pressure is taken. At each interview, manual BP is measured three times in the left arm of seated participants. Children who have difficulty remaining seated are given a computer tablet containing children's video games to ensure they are at rest.

Additional clinical data collection includes DNA (T1 only), height, and weight. Further methods on DNA collection, clinical variable collection (BP, BMI), and laboratory analysis and data analysis structure is described in a companion paper (Taylor et al., 2016).

Psychological Measures (Primary Environmental Exposure [Independent] Variables)

Psychological data will be collected using ACASI, which displays questions and responses on a computer screen, and simultaneously allows participants to hear the question via audio. ACASI minimizes bias that may be present in interviewer-administered surveys, and reduces discomfort that may arise when asking sensitive questions. Variables, conceptual definitions, measurement, and interview time points for data collection are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Variables and Measurement for Psychological Data Collection.

| Variable | Conceptual definition | Description/measure | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSI/SF | Parenting Stress Index, Short Form | Characteristics associated with parenting stress and dysfunctional parenting |

|

| PBC | Parent Behavior Checklist | Multiple aspects of childrearing, including developmental expectations, discipline and nurturing |

|

| PSDQ | Parenting Styles and Dimension Questionnaire | Assesses parenting practices within three parenting typologies: Authoritative, Authoritarian and Permissive |

|

| EOD | Experiences of Discrimination | Measures self-reported experiences of discrimination in adults (women only, children's experiences of discrimination not assessed in this study) in 11 areas including gender, race, age, and skin color |

|

| RES | Race-Related Events Scale | Assesses exposure to stressful and potentially traumatizing experiences of race-related stress in adults (women only, children's experiences of discrimination not assessed in this study) | |

| SOS | Stress Overload Scale | Measures feelings of powerlessness and the burden of demands | |

| CSI | Coping Strategy Indicator | Measures three main coping strategies: Seeking support, Problem Solving, and Avoidance | |

| VIA | Vancouver Index of Acculturation | Acculturation is defined as the process of adaptation to customs, behaviors and attitudes of a new culture;j may influence relationships between experiences of discrimination and health outcomes; assesses two values: Heritage and behaviors associated with Mainstream culture |

|

| BDI | Beck Depression Inventory | Used to assess maternal mental health, including symptoms of sadness, guilt, agitation, sleep loss and appetite loss. | |

| DEM | Demographics | Demographic data (age, gender, education, health insurance status, cigarette smoking, income, employment status, family structure, family health history (including hypertension, birth history) |

|

Note. Demographic variables are collected using ACASI at baseline and updated as needed on subsequent occasions. All other variables are measured on each study occasion using ACASI (T1 = Time 1 (Enrollment); T2 = Time 2 (six months postenrollment); T3 = Time 3 (12 months postenrollment); T4 = Time 4 (18 months postenrollment). ACASI = Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Interviewing.

Potential Confounding and Mediating Factors

Several demographic variables may confound or mediate the relationship between psychological factors and blood pressure. Information on age, gender, education, health insurance status, cigarette smoking, income, employment status, and family structure is collected at T1, and these variables will be considered as potential confounders. Confounders will be selected for inclusion in statistical models using bivariate analyses.

Analytic Aims

The primary study aim for InterGEN is to examine the effects of both genomic (G; candidate gene and epigenetic effects) and psychological environmental factors (E: maternally perceived racial discrimination, mental health, and parenting behavior), as well as G × E interaction on the risk of hypertension in African American mothers and their children. There are three subaims in the study that focus on psychological (environmental) effects on blood pressure of mothers and their young children over a period of two years. The first aim focuses on the examination of the psychological effects of mothers' feelings of perceived racism and discrimination on maternal and child blood pressure. The second aim will investigate the effects of maternal depressive symptoms on blood pressure. Finally, the last aim will examine the effects of mothers' parenting behaviors on blood pressure. Statistical modeling of independent effects of environmental (psychological) exposures and blood pressure readings will be carried out using descriptive statistics and generalized estimating equations (GEE), using an exchangeable correlation structure. GEE models account for repeated measures and correlated data within each individual (Glenn, Stewart, Links, Todd, & Schwartz, 2003; Liang & Zeger, 1986), while controlling for confounders. Models will be run separately for mothers and children, for maternal exposures, and two separate continuous outcomes: systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Power was calculated as greater than 90% based on 20% attrition for 250 families (N = 200), alpha = .05, and a clinically relevant difference of 15 mm Hg.

G × E interaction analyses will examine the synergistic effects between genetic and environmental (psychological) factors. These analyses are described by Taylor and colleagues (2016) in a companion paper. Briefly, interaction effects between single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in candidate genes and environmental factors will be evaluated. African ancestry is a strong predictor of high blood pressure among African Americans, therefore, population admixture/structure will be controlled for in analyses using ancestry-informative marker sets according to established methods (Price et al., 2006). Linear mixed models will be used to account for interrelatedness between mothers and their children, and blood pressure will be modeled using environmental exposures and genomic markers, controlling for confounders.

Implications

The InterGEN Study will investigate how both G × E interactions influence increases in blood pressure among African American women and young children. The proposed research extends nursing science by integrating genetic, epigenetic, and psychological components that can contribute to understanding a more complete picture of why African Americans have the highest incidence of hypertension in the U.S. (Roger et al., 2011). Findings from this study may serve as a platform for development of interventions to reduce risks for hypertension in African American women and children. Health promotion interventions targeted to families early in life—prior to diagnosis of disease—would be optimal for this high-risk population. These interventions may require the expertise and collaborative efforts of multidisciplinary health professionals, including/but not limited to nurses, advanced practice nurses, mental health professionals, counselors, and the like.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge that this study was funded by NIH/NINR (R01NR013520).

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Contributor Information

Cindy A. Crusto, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT and Department of Psychology, University of Pretoria Pretoria, South Africa.

Veronica Barcelona de Mendoza, Yale School of Nursing, Orange, CT.

Christian M. Connell, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT.

Yan V. Sun, Emory University Rollins School of Public Health, Atlanta, GA.

Jacquelyn Y. Taylor, Yale School of Nursing, Orange, CT.

References

- Abidin RR. Parenting stress index (PSI) Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Abraido-Lanza A, White K, Vasques E. Immigrant populations and health. In: Anderson NB, editor. Encyclopedia of health and behavior. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004. pp. 533–537. [Google Scholar]

- Amirkhan JH. A factor analytically derived measure of coping: The Coping Strategy Indicator. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;59:1066–1074. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.59.5.1066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amirkhan JH. Stress overload: A new approach to the assessment of stress. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2012;49:55–71. doi: 10.1007/s10464-011-9438-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artinian NT, Washington OGM, Flack JM, Hockman EM, Jen KLC. Depression, stress, and blood pressure in urban African American women. Progress in Cardiovascular Nursing. 2006;21:68–75. doi: 10.1111/j.0889-7204.2006.04787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Chakravarti A, Cooper RS, Ellison RC, Hunt SC, Province MA, Boerwinkle E. Positional identification of hypertension susceptibility genes on chromosome 2. Hypertension. 2004;43:477–482. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000111585.76299.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review. 1988;8:77–100. doi: 10.1016/0272-7358(88)90050-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berger SL, Kouzarides T, Shiekhattar R, Shilatifard A. An operational definition of epigenetics. Genes & Development. 2009;23:781–783. doi: 10.1101/gad.1787609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Making human beings human: Bioecological perspectives on human development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2005. Article 1. The bioecological theory of human development (2001) pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: Prevalence, treatment, and control of hypertension—United States, 1999-2002 and 2005-2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2011;60:103–108. doi:mm6004a4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, Roccella EJ. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: The JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–2572. doi: 10.1001/JAMA.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crusto CA, Dantzler J, Roberts YH, Hooper LM. Psychometric evaluation of data from the race-related events scale. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development. 2015;48:285–296. doi: 10.1177/0748175615578735. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cundiff JM, Uchino BN, Smith TW, Birmingham W. Socioeconomic status and health: Education and income are independent and joint predictors of ambulatory blood pressure. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2015;38:9–16. doi: 10.1007/s10865-013-9515-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolezsar CM, McGrath JJ, Herzig AJ, Miller SB. Perceived racial discrimination and hypertension: A comprehensive systematic review. Health Psychology. 2014;33:20–34. doi: 10.1037/a0033718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox RA. Parent behavior checklist. Brandon, VT: ProEd; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fraga MF, Ballestar E, Paz MF, Ropero S, Setien F, Ballestar ML, Esteller M. Epigenetic differences arise during the lifetime of monozygotic twins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:10604–10609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500398102. doi:0500398102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass TA, McAtee MJ. Behavioral science at the crossroads in public health: Extending horizons, envisioning the future. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62:1650–1671. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn BS, Stewart WF, Links JM, Todd AC, Schwartz BS. The longitudinal association of lead with blood pressure. Epidemiology. 2003;14:30–36. doi: 10.1097/01.EDE.0000032429.13232.9C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ, Fullerton HJ. Executive summary: Heart disease and stroke statistics—2014 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129:399–410. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000442015.53336.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grothe KB, Dutton GR, Jones GN, Bodenlos J, Ancona M, Brantley PJ. Validation of the Beck Depression Inventory-II in a low-income African American sample of medical outpatients. Psychological Assessment. 2005;17:110–114. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.17.1.110. doi:2005-02422-009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hane AA, Fox NA. Ordinary variations in maternal caregiving influence human infants' stress reactivity. Psychological Science. 2006;17:550–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen ML, Gunn PW, Kaelber DC. Underdiagnosis of hypertension in children and adolescents. JAMA. 2007;298:874–879. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.8.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heijmans BT, Tobi EW, Stein AD, Putter H, Blauw GJ, Susser ES, Lumey LH. Persistent epigenetic differences associated with prenatal exposure to famine in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:17046–17049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806560105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, Hartman C, Barbeau EM. Experiences of discrimination: Validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61:1576–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam LL, Emberly E, Fraser HB, Neumann SM, Chen E, Miller GE, Kobor MS. Factors underlying variable DNA methylation in a human community cohort. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:17253–17260. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121249109/-/DCSupplemental. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. doi: 10.1093/biomet/73.1.13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muntner P, He J, Cutler JA, Wildman RP, Whelton PK. Trends in blood pressure among children and adolescents. JAMA. 2004;291:2107–2113. doi: 10.1001/JAMA.291.17.2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114:555–576. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.2.S2.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuru-Jeter A, Dominguez TP, Hammond WP, Leu J, Skaff M, Egerter S, Braveman P. “It's the skin you're in”: African American women talk about their experiences of racism. An exploratory study to develop measures of racism for birth outcome studies. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2009;13:29–39. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0357-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nwankwo T, Yoon SS, Burt V, Gu Q. Hypertension among adults in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011-2012. NCHS Data Brief. 2013;133:1–8. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db133.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pederson DR, Gleason KE, Moran G, Bento S. Maternal attachment representations, maternal sensitivity, and the infant-mother attachment relationship. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:925–933. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.34.5.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price AL, Patterson NJ, Plenge RM, Weinblatt ME, Shadick NA, Reich D. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nature Genetics. 2006;38:904–909. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts YH, Campbell CA, Ferguson M, Crusto CA. The role of parenting stress in young children's mental health functioning after exposure to family violence. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2013;26:605–612. doi: 10.1002/jts.21842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson CC, Mandleco B, Frost Olsen S, Hart CH. The Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire (PSDQ) In: Perlmutter BF, Touliatos J, Holden GW, editors. Handbook of family measurement techniques Vol 2: Instruments and index. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001. p. 190. [Google Scholar]

- Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Adams RJ, Berry JD, Brown TM, Fox CS. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2011 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:e18–e209. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182009701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryder AG, Alden LE, Paulhus DL. Is acculturation unidimensional or bidimensional? A head-to-head comparison in the prediction of personality, self-identity, and adjustment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:49–65. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.79.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders-Phillips K, Settles-Reaves B, Walker D, Brownlow J. Social inequality and racial discrimination: Risk factors for health disparities in children of color. Pediatrics. 2009;124(Suppl 3):S176–S186. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1100E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein A, Pearson RM, Goodman SH, Rapa E, Rahman A, McCallum M, Pariante CM. Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and child. Lancet. 2014;384:1800–1819. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61277-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J, Sun YV, Chu J, Mosley TH, Kardia SL. Interactions between metallopeptidase 3 polymorphism rs679620 and BMI in predicting blood pressure in African American women with hypertension. Journal of Hypertension. 2008;26:2312–2318. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283110402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JY, Maddox R, Wu CY. Genetic and environmental risks for high blood pressure among African American mothers and daughters. Biological Research for Nursing. 2009;11:53–65. doi: 10.1177/1099800409334817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JY, Sun CY, Wu C, Darling D, Sun YV, Kardia SLR, Jackson JS. Gene-environment effects of SLC4A5 and skin color on blood pressure among African American women. Ethnicity & Disease. 2012;22:155–161. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JY, Washington OGM, Artinian NT, Lichtenberg P. Parental stress among African American parents and grandparents. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2007;28:373–387. doi: 10.1080/01612840701244466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JY, Wright ML, Crusto CA, Sun YV. The intergenerational impact of genetic and psychological factors on blood pressure study (InterGEN): Design and methods for complex DNA analysis. Biological Research for Nursing. 2016 doi: 10.1177/1099800416645399. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tebes JK. Community psychology for this century: Perspectives on the future of the field from the generations after Swampscott. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2016 doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12110. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tudge JRH, Mokrova I, Hatfield BE, Karnik RB. Uses and misuses of Bronfenbrenner's bioecological theory of human development. Journal of Family Theory & Review. 2009;1:198–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-2589.2009.00026.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waelde LC, Pennington D, Mahan C, Mahan R, Kabour M, Marquett R. Psychometric properties of the race-related events scale. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2010;2:4–11. doi: 10.1037/a0019018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wright MO, Masten AS, Narayan AJ. Resilience processes in development: Four waves of research on positive adaptation in the context of adversity. In: Goldstein S, Brooks RB, editors. Handbook of resilience in children. 2. New York, NY: Springer; 2013. pp. 15–37. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wung SF, Hickey KT, Taylor JY, Gallek MJ. Cardiovascular genomics. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2013;45:60–68. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.