Abstract

It is generally well‐accepted that the immune system is a significant contributor in the pathogenesis of hypertension. Specifically, activated and pro‐inflammatory T‐lymphocytes located primarily in the vasculature and kidneys appear to have a causal role in exacerbating elevated blood pressure. It has been proposed that increased sympathetic nerve activity and noradrenaline outflow associated with hypertension may be primary contributors to the initial activation of the immune system early in the disease progression. However, it has been repeatedly demonstrated in many different human and experimental diseases that sympathoexcitation is immunosuppressive in nature. Moreover, human hypertensive patients have demonstrated increased susceptibility to secondary immune insults like infections. Thus, it is plausible, and perhaps even likely, that in diseases like hypertension, specific immune cells are activated by increased noradrenaline, while others are in fact suppressed. We propose a model in which this differential regulation is based upon activation status of the immune cell as well as the resident organ. With this, the concept of global immunosuppression is obfuscated as a viable target for hypertension treatment, and we put forth the concept of focused organ‐specific immunotherapy as an alternative option.

Abbreviations

- AngII

angiotensin II

- NA

noradrenaline

- TNFα

tumour necrosis factor α

Introduction

The immune system is a functional network of diverse cells and proteins that are involved in the regulation of virtually every organ system in the body. The contribution of the immune system, particularly T‐lymphocytes, to hypertension is becoming well accepted, but the mechanistic processes preceding activation of immune cells in the setting of hypertension are not fully understood. One hallmark of both human and experimental hypertension is enhanced sympathetic nerve activity leading to elevated levels of local and circulating noradrenaline (NA) (Seravalle et al. 2014; Grassi et al. 2015), and this sympathoexcitation has been suggested to be causal in mounting the inappropriate inflammatory response that increases blood pressure (Xiao et al. 2015). However, over the last few decades a breadth of data has emerged from the field of immunology examining the anti‐inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects of NA in immune cells, including T‐lymphocytes. Understanding that indeed both the sympathetic nervous and immune systems contribute to the development and perpetuation of hypertension, we put forth a model of spatially mediated crosstalk between the two systems that leads to differential regulation in an organ‐specific manner.

Current understanding of T‐lymphocytes in hypertension

The fundamental understanding of the role of the immune system in hypertension began with the work of forerunning investigators like Grollman, Olsen and Svendsen in the 1960s and 1970s (White & Grollman, 1964; Okuda & Grollman, 1967; Olsen, 1970, 1971; Svendsen, 1973, 1978). These principal studies illuminated the concept that alterations in the immune system were causal in the development of increased blood pressure. Later, this line of investigation was continued by Bernardo Rodriguez‐Iturbe and colleagues who extended the original findings, examining the role of immune cells specifically in the kidney (Rodriguez‐Iturbe et al. 2002). Their studies elucidated that suppression of primarily lymphocytes utilizing the drug mycophenolate mofetil could reverse both experimental and human hypertension, and proposed a mechanism for the disease based on immune‐driven renal damage leading to increased sodium reabsorption and a right‐shifted pressure–natriuresis relationship (Rodriguez‐Iturbe et al. 2001; Herrera et al. 2006). However, it was not until 2007 that T‐lymphocytes were discovered to have a true causal role in the exacerbation of hypertension. Using a genetic mouse model of T‐ and B‐lymphocyte immunodeficiency (i.e. Rag1−/−), Harrison and colleagues confirmed the observation that immunodeficient animals displayed blunted hypertensive responses to several challenges (Guzik et al. 2007). The novel observation in this pivotal study was that restoration of only the T‐lymphocyte population in these animals could restore the blood pressure to control levels, thus revealing the causative nature these immune cells play in hypertension.

Since this time, a preponderance of research has emerged examining the mechanistic nature of T‐lymphocytes and immune cells in driving the development of hypertension. Several investigations have definitively demonstrated that the primary sites of T‐lymphocyte‐driven inflammation in hypertension are the kidneys, vasculature and brain (Theuer et al. 2002; Guzik et al. 2007; Shi et al. 2010; Saleh et al. 2015), with additional evidence also suggesting T‐lymphocyte involvement in the skin interstitium (Wiig et al. 2013). While T‐lymphocytes remain the primary effector cell type exacerbating hypertension, the focus in the field has recently shifted to antigen‐presenting dendritic cells as potential upstream activators of the T‐lymphocytes. Mice lacking the B7/CD28 co‐stimulatory axis, which is necessary for T‐lymphocyte activation by antigen‐presenting dendritic cells, demonstrated blunted pressor responses, suggesting a contributory role of dendritic cells in the activation of T‐lymphocytes during hypertension (Vinh et al. 2010). This work was recently extended by elucidating that dendritic cells potentially become activated due to the accumulation of oxidatively modified cross‐linked protein products, particularly isoketal‐modified proteins (Kirabo et al. 2014). Increased oxidation of arachidonic acid causes the formation of reactive γ‐ketoaldehydes (also known as isoketals), which can cross‐link proteins forming novel epitopes the immune system may recognize as foreign. Scavenging these isoketals resulted in decreased dendritic cell activation and blunted pressor responses (Kirabo et al. 2014), suggesting these reactive ketoaldehydes may be an essential component in the activation of T‐lymphocytes driving hypertension.

While this elegant mechanism details the links between activating T‐lymphocytes by antigen presenting cells, the upstream signal that leads to the initial activation of the immune system remains unclear. The majority of experimental models examining T‐lymphocytes in hypertension rely on the chronic peripheral infusion of angiotensin II (AngII), which suggests this pro‐hypertensive compound may be a primary mediator of immune system activation. However, while AngII infusion leads to activated immune cells in vivo, evidence indicating that AngII directly activates immune cells, especially T‐lymphocytes, is complex. For example, we have observed that direct stimulation of isolated splenic T‐lymphocytes with exogenous AngII fails to significantly induce or augment activation of these cells (unpublished data). Furthermore, T‐lymphocytes lacking the angiotensin type 1 receptor have potentiated pro‐inflammatory cytokine production, suggesting AngII may have protective roles in attenuating or controlling inflammation (Zhang et al. 2012). In contrast, Hoch et al. (2009) demonstrated that AngII produced endogenously by T‐lymphocytes appears necessary for a complete activation response. Taken together, the direct action of AngII on T‐lymphocytes appears intricate in nature, and further investigations are warranted to elucidate the exact mechanism of how this pro‐hypertensive peptide regulates T‐lymphocyte activation.

In vivo, the effects of AngII on T‐lymphocytes are further convoluted due to the multitude of non‐direct effects AngII may have on the immune system. For example, chronic infusion of AngII leads to an imbalance of sodium and water handling, and the presence of increased salt has been shown to amplify the activation and differentiation of T‐lymphocytes into a pro‐inflammatory TH17 state (Kleinewietfeld et al. 2013). These T‐lymphocyte subtypes are known to be increased in various forms of experimental hypertension (Harrison et al. 2012; Kleinewietfeld et al. 2013), and as such, AngII may be indirectly leading to T‐lymphocyte activation by means of increased salt. Additionally, AngII has been shown to act centrally in cardiovascular control regions in the brain to enhance sympathetic outflow in the periphery and further elevate blood pressure (Zimmerman et al. 2002; Zimmerman et al. 2004). Ganta and colleagues demonstrated that centrally administered AngII could increase peripheral sympathetic drive as well as immune cell‐driven pro‐inflammatory cytokine production (Ganta et al. 2005), again suggesting a non‐direct effect of AngII in the modulation of immune cells and furthering the complexity of how this effector peptide of the renin–angiotensin system regulates the immune system. This latter dataset combined with newer evidence (Xiao et al. 2015) suggests increased sympathetic drive may be the primary perpetrator of immune system activation during hypertension, but the governing effects of the sympathetic nervous system on the immune system are multifaceted, and suggest differential regulation depending on the model system or organ examined.

Sympathoexcitation‐induced suppression of T‐lymphocytes

The autonomic nervous system innervates virtually every organ system in the body, and is integral to the homeostatic regulation and function of the various cell types residing in these systems. Organs of the immune system (i.e. spleen, lymph nodes and bone marrow) are no exception, though their innervation is highly unique and quite diverse from other organ systems. It has been well documented that these primary and secondary lymphoid organs are exclusively innervated through sympathetic efferent nerves, and thus lack any direct parasympathetic innervation (Nance & Sanders, 2007). Furthermore, this sympathetic neural input displays unique synaptic anatomy in these lymphoid organs, as the tyrosine hydroxylase positive neurons that synthesize NA terminate in close proximity (approximately 6 nm) to lymphocytes (Felten & Olschowka, 1987). Due to limited reuptake of NA at these so called neuroimmune synapses, local concentrations of the catecholamine in vivo can reach in excess of 1 mm (Felten et al. 1987), which has been shown to have negative regulatory effects on resident T‐lymphocytes.

For instance, intravenous lipopolysaccharide (LPS) injection is well documented to increase splenic and plasma levels of the pro‐inflammatory cytokine tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα). Meltzer et al. (2004) demonstrated that circulating and splenic TNFα levels could be significantly suppressed if sympathetic tone was increased during an LPS injection. Moreover, removal of the splenic sympathetic nerve during this challenge reversed this immunosuppression, further suggesting NA‐mediated immune suppression (Meltzer et al. 2004). Additionally, several other studies utilizing adrenergic blockers, ganglionic blockade, or physical ablation of sympathetic nerves have demonstrated augmented immune responses suggesting sympathetic‐derived NA attenuates inflammatory responses (Cunnick et al. 1990; Dobbs et al. 1993; Martelli et al. 2014). Sympathetic drive‐mediated immunodepression may be most well described during cerebrovascular incidents, or stroke. In fact, it has been reported that 23–65% of patients experience complications with infections within the first few days after having a stroke, which is known as stroke‐induced immunodepression syndrome (Langhorne et al. 2000). The effects on the immune system observed during stroke include a decrease in peripheral T‐lymphocytes, impaired early T‐lymphocyte activation, inhibited production of pro‐inflammatory cytokines, and a shift to TH2 polarized lymphocytes (Prass et al. 2003). Moreover, experimental studies have demonstrated that many of the immunological effects of stroke are due primarily to increased sympathetic drive, as adrenergic blockade could reverse many of the depressive effects in T‐lymphocytes (Prass et al. 2003; Walter et al. 2013; Mracsko et al. 2014; Yan & Zhang, 2014). Recently, we have shown NA suppresses the activation of splenic T‐lymphocytes in a model of sympathoexcitation‐driven hypertension, which further extends the role of NA‐driven immunosuppression in cardiovascular diseases (Case & Zimmerman, 2015). However, similar to AngII, NA‐mediated direct and indirect effects on T‐lymphocytes are multidimensional and not yet fully understood.

T‐lymphocytes have been shown to express both α and β adrenergic receptors, but the specific subtype and expression level is complexly regulated and dependent on an array of factors such as species, age, organ in which the cell was isolated, as well as activation and polarization status (Kohm & Sanders, 2001; Kin & Sanders, 2006; Takayanagi et al. 2012). Of the adrenergic receptors, much research has implicated the β2 subtype as the primary receptor involved in NA‐mediated regulation of T‐lymphocytes. Early studies using entire T‐lymphocyte populations observed that stimulation of the β2 receptor led to an inhibition of T‐lymphocyte growth in a cyclic AMP (cAMP)‐dependent manner (Feldman et al. 1987; Novak & Rothenberg, 1990; Tamir & Isakov, 1991). Additionally, purified naive CD4+ T‐lymphocytes have also been shown to be inhibited in growth and cytokine production when exposed to either NA or a β2‐agonist (Ramer‐Quinn et al. 2000; Swanson et al. 2001). Furthermore, evidence suggesting that increased NA promotes a shift from the pro‐inflammatory TH1 to the anti‐inflammatory TH2 T‐lymphocyte subtype has emerged (Wahle et al. 2006; Hou et al. 2013). The data supporting this observation show that NA directly inhibits interleukin 12 (IL‐12) production from dendritic cells, which is necessary for TH1 differentiation of T‐lymphocytes (Panina‐Bordignon et al. 1997; Goyarts et al. 2008). Moreover, the more anti‐inflammatory TH2 T‐lymphocyte appears resistant to the effects of NA, and this is most likely to be attributable to the epigenetic loss of the β2 receptor in these cells (Ramer‐Quinn et al. 1997; McAlees et al. 2011). Overall, both in vitro and in vivo evidence strongly suggests NA has direct suppressive effects on naive T‐lymphocytes as well as promoting an anti‐inflammatory environment.

We have elucidated that NA mediates its inhibitory effects in naive splenic T‐lymphocytes at least in part due to increased redox signalling, a paradigm that remains unexplored in the catecholaminergic signalling of immune cells to date. Both CD4+ and CD8+ T‐lymphocytes demonstrated increased intracellular superoxide levels after being exposed to NA, and using a mouse model of NA infusion to mimic sympathoexcitation‐mediated hypertension, we observed that the inhibitory effects of NA on T‐lymphocytes could be partially rescued when the animals were treated with the superoxide scavenger Tempol (Case & Zimmerman, 2015). Recently, work from Fadel and colleagues also observed increased superoxide in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) when exposed to NA (Deo et al. 2013). PBMCs consist of T‐lymphocytes, B‐lymphocytes and monocytes, which suggests the potential for NA‐mediated redox signalling in an array of immune cells. Moreover, this work identified that the primary adrenergic receptor driving the superoxide production was α2 (Deo et al. 2013), and current work from our laboratory also suggests NA‐mediated superoxide production in T‐lymphocytes may be α adrenergic receptor mediated as well (unpublished data). Additionally, β2 adrenergic receptor knock‐out dendritic cells produced the same amount of intracellular oxidatively driven isoketals as control cells when exposed to NA (Xiao et al. 2015), which expounds upon the hypothesis that the redox effects of NA may not be mediated solely through the β2 adrenergic receptor like other inhibitory effects on immune cells as previously discussed. Overall, the understanding of catecholamine‐driven redox signalling and its downstream effects in immune cells is still in its infancy, and remains an attractive area where the field may progress in the future.

Sympathoexcitation‐induced activation of T‐lymphocytes

While a breadth of data exists demonstrating the suppressive effects of NA on T‐lymphocytes, there is evidence suggesting that NA in fact potentiates the pro‐inflammatory effects of these adaptive immune cells. Although NA appears to have direct inhibitory effects on naive T‐lymphocytes as previously discussed, the effect on activated T‐lymphocytes is pro‐inflammatory in nature. For example, activated and polarized pro‐inflammatory TH1 T‐lymphocytes were shown to produce higher amounts of interferon γ (IFNγ) when re‐stimulated in the presence of NA (Sanders et al. 1997; Swanson et al. 2001). The difference in response between naive and activated T‐lymphocytes suggests the potential for a complex crosstalk of intracellular cAMP levels affecting T‐cell receptor (TCR) activation threshold and/or transcription factor expression and function. Additionally, NA was shown to enhance the pro‐inflammatory signature in purified macrophages stimulated with LPS (Huang et al. 2012). Most notably, bone derived dendritic cells that were exposed to adrenergic agonists during antigen presentation were shown to cause increases in IL‐17 production in CD4+ T‐lymphocytes, and promoted differentiation to a TH17 state (Kim & Jones, 2010). This finding has significant relevance to hypertension, as dendritic cells and TH17 T‐lymphocytes have been highly implicated as previously discussed (Harrison et al. 2012).

In addition to in vitro observations of NA‐mediated pro‐inflammatory effects, in vivo studies have also suggested that increased sympathetic drive enhances immune responses. For example, mice lacking dopamine β‐hydroxylase (required for NA production) demonstrated decreased immune responses to various challenges, suggesting NA was essential in maintaining proper immunocompetency (Alaniz et al. 1999). Similarly, systemic chemical sympathectomy reduced delayed hypersensitivity reactions to a sensitizing agent, further arguing for the need of NA in mounting a normal immune response (Madden et al. 1989). In addition, patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), an autoimmune disease with increased sympathetic drive, display a higher number of pro‐inflammatory TH1 and TH17 T‐lymphocytes (Firestein, 2003; Mellado et al. 2015). Moreover, RA patients treated with β antagonists or β agonists during the development of the disease observe limited or exacerbated disease progression, respectively (Levine et al. 1988; Lubahn et al. 2004). Together, these findings lead to the prospect of NA potentiating pro‐inflammatory and autoimmune events, which may be directly related to what is observed in hypertension.

It has been proposed that increased sympathetic drive leading to elevated NA may be the direct upstream initiator of immune system activation during hypertension. Increased sympathetic nerve activity is highly associated with both experimental and human hypertension (Seravalle et al. 2014; Grassi et al. 2015). Additionally, it has been demonstrated that AngII may have direct effects on the central nervous system in enhancing systemic sympathetic nerve activity, which has been shown to enhance pro‐inflammatory cytokine production from immune cells (Ganta et al. 2005). Moreover, attenuation of increased sympathetic outflow by ablation of the anteroventral tissue lining the third ventricle of the brain (AV3V) not only decreases blood pressure, but hinders the activation of peripheral T‐lymphocytes in the aorta during AngII‐mediated hypertension (Marvar et al. 2010). These data further suggest a limited role for AngII in the direct activation of the immune system, but propose a sympathetic‐mediated mechanism for downstream T‐lymphocyte activation. Recently, Harrison and colleagues elucidated that removal of sympathetic efferent nerves to the kidney through renal denervation not only decreased AngII‐mediated hypertension, but also attenuated isoketal formation in dendritic cells, the number of activated dendritic cells, and T‐lymphocyte activation within the kidneys (Xiao et al. 2015). Together, these data imply that increased accumulation of NA in the kidneys and/or vasculature is a driving force in the activation of T‐lymphocytes and the exacerbation of hypertension, and due to this, the concept of immunosuppression to treat the disease is becoming popular.

Implications for targeting the immune system for hypertension therapy

As previously discussed, the use of lymphocyte‐targeted immunosuppressant drugs has been shown to attenuate both experimental and human hypertension (Rodriguez‐Iturbe et al. 2001; Herrera et al. 2006). These broad spectrum immunosuppressants target and constrain both T‐ and B‐lymphocytes, and as such will most likely not be an attractive method for hypertension therapy. Conversely, modulation of the immune system through specific immunotherapy has been heralded as one of the biggest breakthroughs in recent years for diseases such as cancer and autoimmunity (Couzin‐Frankel, 2013). T‐lymphocytes are one of the principal targets of immunotherapy, which makes this option enticing for hypertension. Altering T‐lymphocyte function through immunotherapy is primarily achieved through the binding of either agonist or antagonist antibodies to various co‐stimulatory surface molecules used in the normal regulation of T‐lymphocyte activation (Couzin‐Frankel, 2013). Harrison and colleagues employed a similar approach in an experimental model of hypertension demonstrating that elimination of the B7/CD28 axis with a CTLA4‐Ig fusion protein/antibody could ablate AngII and deoxycorticosterone acetate salt‐mediated increases in blood pressure (Vinh et al. 2010). While these findings are indeed promising in the context of hypertensive therapy, this study did not perform any examination on the residual immunocompetency of these animals during or after therapy. Although evidence suggests that hypertensive animals possess significant inflammation in sites such as the kidneys, vasculature and brain (Harrison et al. 2011, 2012), our findings combined with the extensive literature on sympathoexcitation‐mediated immunodepression (Feldman et al. 1987; Cunnick et al. 1990; Dobbs et al. 1993; Takayanagi et al. 2012; Case & Zimmerman, 2015) suggest an immunosuppressed state within the lymphoid organs, which may predispose hypertensive patients or animals to secondary infections. However, the link between hypertension and the ability of the immune system to fight secondary infections remains undeveloped.

A breadth of data exists elucidating the association of various types of infections such as cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, Chlamydia pneumoniae and Helicobacter pylori with hypertension (Lip et al. 1996; Cook et al. 1998; Pitiriga et al. 2003; Blanc et al. 2004; Sun et al. 2004; Haarala et al. 2012; Li et al. 2012; Vahdat et al. 2013). However, all of these studies have taken the perspective that the infections predispose individuals to hypertension, but it is possible that the converse is true and that it is the hypertension that leads to increased infections with these various pathogens. Moreover, several clinical studies have demonstrated direct associations with hypertension and increased risk of infections. In a large retrospective cohort study, it was observed that withholding blood pressure control after surgery led to a significant risk of infection‐related complications such as urinary tract infections or sepsis (Lee et al. 2015). Another investigation demonstrated that wound healing was delayed and posed an increased threat of systemic infection in hypertensive patients, thus further suggesting an immunodepressed state with elevated blood pressure (Ahmed et al. 2011). The idea that hypertension itself is a causal mediator of increased risk of infection is an area of research that needs further investigation, especially as the push for immune‐based therapy for hypertension is gaining significant traction. On this point, it is tempting to speculate that administration of systemic immunosuppressants in the goal of ameliorating hypertension may also limit bystander immune function in lymphatic organs, which could have severe unforeseen negative consequences in regards to secondary infections or immune complications. Due to this, the concept of site‐specific or organ‐targeted immune therapy for hypertension must be carefully considered. For example, one could envision an immune‐modulating antibody cross‐linked to a nanoparticle or aptamer that specifically binds targeted cells. By this methodology, the immunotherapy would be directly delivered to the site of inflammation (i.e. kidney, vasculature, brain) leaving resident immune cells in other organs undisturbed and able to mount proper immune reactions in the event of a secondary insult. While these therapies have not yet been developed to date, this is an exciting approach to consider when moving forward with targeting the immune system for hypertension therapy, so as not to eliminate one disease by replacing it with another.

Conclusion

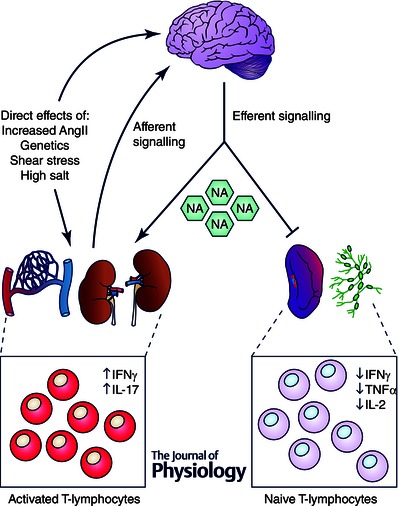

Taken together, the evidence suggests that increased sympathetic outflow may directly attenuate the ability of naive T‐lymphocytes to become fully activated, while also exacerbating the inflammatory effects of activated T‐lymphocytes. Hypertension is a disease associated with increased sympathetic outflow, and this augmented sympathetic tone perpetuates and exacerbates the disease. Due to this, we propose a hypertension model in which activation and suppression of the immune system by increased NA occur simultaneously, but within different compartments (Fig. 1). In this model, risk factors such as increased salt intake, genetic predisposition, or elevated AngII levels may have direct effects on the central nervous system in increasing sympathetic tone. Additionally, these risk factors increase pressure and sheer stress‐mediated damage at vulnerable sites such as the kidney or microvasculature. This leads to a localized inflammation initiated primarily by the innate immune system (i.e. neutrophils, macrophages, dendritic cells, etc.) in attempts to repair the injured site. The localized tissue disruption may also lead to increased formation of oxidative byproducts such as isoketals, which may further enhance the activation of innate immune cells such as dendritic cells. These activated dendritic cells are then capable of activating T‐lymphocytes, and causing the increased proliferation and pro‐inflammatory function of these adaptive immune cells. This local inflammation triggers additional increases in sympathetic outflow through the central nervous system, but the mechanisms underlying this crosstalk have yet to be fully identified. It is at this point during increased sympathetic drive that the effects of the immune system diverge in various compartments. Due to the T‐lymphocytes in the kidney and vasculature being already polarized and activated, it is likely that the increase in NA produced from the increase in sympathetic nerve activity augments their pro‐inflammatory potential. This may lead to increased tissue damage, sodium and water mishandling, and even further elevated sympathetic drive, all of which exacerbate the severity of the underlying hypertension. In contrast, the systemic increase in sympathetic outflow will have effects on other organs such as the spleen and lymph nodes (aforementioned, where the T‐lymphocytes will be exposed to exorbitant levels of NA due to the tight neuroimmune junctions in these organs). Here, the majority of the T‐lymphocytes remain naive and are not involved with the inflammatory response localized to the kidney or vasculature. We have demonstrated that these naive cells exposed to increased NA undergo a form of reprogramming that renders them inhibited upon activation (Case & Zimmerman, 2015), which suggests the potential for a secondary immunodeficiency in patients with diseases of increased sympathetic drive, like hypertension. Overall, this Janus‐faced sympathetic nervous system regulation of the immune system creates a challenging problem when therapeutically targeting the immune system in hypertension, as current non‐specific modalities of therapy may treat the elevated blood pressure, but may exacerbate an already immuncompromised state as well.

Figure 1.

Proposed model for the opposing effects of increased sympathetic drive on T‐lymphocytes in hypertension

Numerous factors such as increased AngII, genetic predisposition, shear stress, or high salt have been shown to elicit damage to susceptible organs such as the vasculature and kidney, while additionally having direct effects on the central nervous system (CNS). This damage can lead to a localized inflammatory response in which T‐lymphocytes become activated and polarized producing cytokines such as IFNγ and IL‐17. It is believed that this inflammation is detected in the brain via afferent nerve pathways, further increases in circulating AngII, and pro‐inflammatory cytokines, which in turn triggers increased efferent sympathetic nerve activity and NA outflow. In sites where T‐lymphocytes are activated and polarized (i.e. vasculature and kidney), NA potentiates the inflammation, while NA has direct inhibitory effects on naive T‐lymphocytes localized to lymphoid organs such as the spleen or lymph nodes.

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to report.

Author contributions

Both authors have approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All persons designated as authors qualify for authorship, and all those who qualify for authorship are listed.

Funding

The authors of this review are supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 HL103942 to M.C.Z. and K99 HL123471 to A.J.C) and the American Heart Association (14GRNT20390010 to M.C.Z.).

Biographies

Adam J. Case is a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Cellular and Integrative Physiology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC) in Omaha, NE. He earned his PhD in Free Radical and Radiation Biology from the University of Iowa. His primary research interests entail investigating the role of redox signalling in the immune system and how it pertains to cardiovascular disease.

Matthew C. Zimmerman is an Associate Professor in the Department of Cellular and Integrative Physiology and Director of the Free Radicals in Medicine Program at the University of Nebraska Medical Center. He earned his PhD in Anatomy and Cell Biology from the University of Iowa in Iowa City, IA. He received post‐doctoral training in the Free Radical and Radiation Biology Program at the University of Iowa. His research program focuses on the role of oxidants and antioxidants in the central nervous system in the pathogenesis of hypertension.

References

- Ahmed AA, Mooar PA, Kleiner M, Torg JS & Miyamoto CT (2011). Hypertensive patients show delayed wound healing following total hip arthroplasty. PloS One 6, e23224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alaniz RC, Thomas SA, Perez‐Melgosa M, Mueller K, Farr AG, Palmiter RD & Wilson CB (1999). Dopamine β‐hydroxylase deficiency impairs cellular immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96, 2274–2278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc P, Corsi AM, Gabbuti A, Peduzzi C, Meacci F, Olivieri F, Lauretani F, Francesco M & Ferrucci L (2004). Chlamydia pneumoniae seropositivity and cardiovascular risk factors: The InCHIANTI Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 52, 1626–1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case AJ & Zimmerman MC (2015). Redox‐regulated suppression of splenic T‐lymphocyte activation in a model of sympathoexcitation. Hypertension 65, 916–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook PJ, Lip GY, Davies P, Beevers DG, Wise R & Honeybourne D (1998). Chlamydia pneumoniae antibodies in severe essential hypertension. Hypertension 31, 589–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couzin‐Frankel J (2013). Breakthrough of the year 2013. Cancer immunotherapy. Science 342, 1432–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunnick JE, Lysle DT, Kucinski BJ & Rabin BS (1990). Evidence that shock‐induced immune suppression is mediated by adrenal hormones and peripheral β‐adrenergic receptors. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 36, 645–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deo SH, Jenkins NT, Padilla J, Parrish AR & Fadel PJ (2013). Norepinephrine increases NADPH oxidase‐derived superoxide in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells via α‐adrenergic receptors. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 305, R1124–R1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs CM, Vasquez M, Glaser R & Sheridan JF (1993). Mechanisms of stress‐induced modulation of viral pathogenesis and immunity. J Neuroimmunol 48, 151–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman RD, Hunninghake GW & McArdle WL (1987). Beta‐adrenergic‐receptor‐mediated suppression of interleukin 2 receptors in human lymphocytes. J Immunol 139, 3355–3359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felten DL, Felten SY, Bellinger DL, Carlson SL, Ackerman KD, Madden KS, Olschowki JA & Livnat S (1987). Noradrenergic sympathetic neural interactions with the immune system: structure and function. Immunol Rev 100, 225–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felten SY & Olschowka J (1987). Noradrenergic sympathetic innervation of the spleen: II. Tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)‐positive nerve terminals form synapticlike contacts on lymphocytes in the splenic white pulp. J Neurosci Res 18, 37–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firestein GS (2003). Evolving concepts of rheumatoid arthritis. Nature 423, 356–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganta CK, Lu N, Helwig BG, Blecha F, Ganta RR, Zheng L, Ross CR, Musch TI, Fels RJ & Kenney MJ (2005). Central angiotensin II‐enhanced splenic cytokine gene expression is mediated by the sympathetic nervous system. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289, H1683–H1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyarts E, Matsui M, Mammone T, Bender AM, Wagner JA, Maes D & Granstein RD (2008). Norepinephrine modulates human dendritic cell activation by altering cytokine release. Exp Dermatol 17, 188–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassi G, Mark A & Esler M (2015). The sympathetic nervous system alterations in human hypertension. Circ Res 116, 976–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzik TJ, Hoch NE, Brown KA, McCann LA, Rahman A, Dikalov S, Goronzy J, Weyand C & Harrison DG (2007). Role of the T cell in the genesis of angiotensin II induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. J Exp Med 204, 2449–2460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haarala A, Kahonen M, Lehtimaki T, Aittoniemi J, Jylhava J, Hutri‐Kahonen N, Taittonen L, Laitinen T, Juonala M, Viikari J, Raitakari OT & Hurme M (2012). Relation of high cytomegalovirus antibody titres to blood pressure and brachial artery flow‐mediated dilation in young men: the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Clin Exp Immunol 167, 309–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison DG, Guzik TJ, Lob HE, Madhur MS, Marvar PJ, Thabet SR, Vinh A & Weyand CM (2011). Inflammation, immunity, and hypertension. Hypertension 57, 132–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison DG, Marvar PJ & Titze JM (2012). Vascular inflammatory cells in hypertension. Front Physiol 3, 128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera J, Ferrebuz A, MacGregor EG & Rodriguez‐Iturbe B (2006). Mycophenolate mofetil treatment improves hypertension in patients with psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 17, S218–S225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoch NE, Guzik TJ, Chen W, Deans T, Maalouf SA, Gratze P, Weyand C & Harrison DG (2009). Regulation of T‐cell function by endogenously produced angiotensin II. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 296, R208–R216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou N, Zhang X, Zhao L, Zhao X, Li Z, Song T & Huang C (2013). A novel chronic stress‐induced shift in the Th1 to Th2 response promotes colon cancer growth. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 439, 471–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang JL, Zhang YL, Wang CC, Zhou JR, Ma Q, Wang X, Shen XH & Jiang CL (2012). Enhanced phosphorylation of MAPKs by NE promotes TNF‐α production by macrophage through α adrenergic receptor. Inflammation 35, 527–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BJ & Jones HP (2010). Epinephrine‐primed murine bone marrow‐derived dendritic cells facilitate production of IL‐17A and IL‐4 but not IFN‐γ by CD4+ T cells. Brain Behav Immun 24, 1126–1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kin NW & Sanders VM (2006). It takes nerve to tell T and B cells what to do. J Leukoc Biol 79, 1093–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirabo A, Fontana V, de Faria AP, Loperena R, Galindo CL, Wu J, Bikineyeva AT, Dikalov S, Xiao L, Chen W, Saleh MA, Trott DW, Itani HA, Vinh A, Amarnath V, Amarnath K, Guzik TJ, Bernstein KE, Shen XZ, Shyr Y, Chen SC, Mernaugh RL, Laffer CL, Elijovich F, Davies SS, Moreno H, Madhur MS, Roberts J 2nd & Harrison DG (2014). DC isoketal‐modified proteins activate T cells and promote hypertension. J Clin Investig 124, 4642–4656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinewietfeld M, Manzel A, Titze J, Kvakan H, Yosef N, Linker RA, Muller DN & Hafler DA (2013). Sodium chloride drives autoimmune disease by the induction of pathogenic TH17 cells. Nature 496, 518–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohm AP & Sanders VM (2001). Norepinephrine and β2‐adrenergic receptor stimulation regulate CD4+ T and B lymphocyte function in vitro and in vivo. Pharmacol Rev 53, 487–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhorne P, Stott DJ, Robertson L, MacDonald J, Jones L, McAlpine C, Dick F, Taylor GS & Murray G (2000). Medical complications after stroke: a multicenter study. Stroke 31, 1223–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SM, Takemoto S & Wallace AW (2015). Association between withholding angiotensin receptor blockers in the early postoperative period and 30‐day mortality: a cohort study of the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System. Anesthesiology 123, 288–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine JD, Coderre TJ, Helms C & Basbaum AI (1988). β2‐Adrenergic mechanisms in experimental arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85, 4553–4556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Samaranayake NR, Ong KL, Wong HK & Cheung BM (2012). Is human cytomegalovirus infection associated with hypertension? The United States National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2002. PloS One 7, e39760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lip GH, Wise R & Beevers G (1996). Association of Helicobacter pylori infection with coronary heart disease. Study shows association between H pylori infection and hypertension. BMJ 312, 250–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubahn CL, Schaller JA, Bellinger DL, Sweeney S & Lorton D (2004). The importance of timing of adrenergic drug delivery in relation to the induction and onset of adjuvant‐induced arthritis. Brain Behav Immun 18, 563–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAlees JW, Smith LT, Erbe RS, Jarjoura D, Ponzio NM & Sanders VM (2011). Epigenetic regulation of beta2‐adrenergic receptor expression in TH1 and TH2 cells. Brain Behav Immun 25, 408–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden KS, Felten SY, Felten DL, Sundaresan PR & Livnat S (1989). Sympathetic neural modulation of the immune system. I. Depression of T cell immunity in vivo and vitro following chemical sympathectomy. Brain Behav Immun 3, 72–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martelli D, Yao ST, McKinley MJ & McAllen RM (2014). Reflex control of inflammation by sympathetic nerves, not the vagus. J Physiol 592, 1677–1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marvar PJ, Thabet SR, Guzik TJ, Lob HE, McCann LA, Weyand C, Gordon FJ & Harrison DG (2010). Central and peripheral mechanisms of T‐lymphocyte activation and vascular inflammation produced by angiotensin II‐induced hypertension. Circ Res 107, 263–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellado M, Martinez‐Munoz L, Cascio G, Lucas P, Pablos JL & Rodriguez‐Frade JM (2015). T cell migration in rheumatoid arthritis. Front Immunol 6, 384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer JC, MacNeil BJ, Sanders V, Pylypas S, Jansen AH, Greenberg AH & Nance DM (2004). Stress‐induced suppression of in vivo splenic cytokine production in the rat by neural and hormonal mechanisms. Brain Behav Immun 18, 262–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mracsko E, Liesz A, Karcher S, Zorn M, Bari F & Veltkamp R (2014). Differential effects of sympathetic nervous system and hypothalamic‐pituitary‐adrenal axis on systemic immune cells after severe experimental stroke. Brain Behav Immun 41, 200–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nance DM & Sanders VM (2007). Autonomic innervation and regulation of the immune system (1987‐2007). Brain Behav Immun 21, 736–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak TJ & Rothenberg EV (1990). cAMP inhibits induction of interleukin 2 but not of interleukin 4 in T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87, 9353–9357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda T & Grollman A (1967). Passive transfer of autoimmune induced hypertension in the rat by lymph node cells. Tex Rep Biol Med 25, 257–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen F (1970). Type and course of the inflammatory cellular reaction in acute angiotensin‐hypertensive vascular disease in rats. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand A 78, 143–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen F (1971). Inflammatory cellular reaction in hypertensive vascular disease. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand Suppl 220, 1–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panina‐Bordignon P, Mazzeo D, Lucia PD, D'Ambrosio D, Lang R, Fabbri L, Self C & Sinigaglia F (1997). β2‐Agonists prevent Th1 development by selective inhibition of interleukin 12. J Clin Invest 100, 1513–1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitiriga V, Kotsis VT, Alexandrou ME, Petrocheilou‐Paschou VD, Kokolakis N, Zakopoulou RN & Zakopoulos NA (2003). Increased prevalence of Chlamydophila pneumoniae but not Epstein–Barr antibodies in essential hypertensives. J Hum Hypertens 17, 21–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prass K, Meisel C, Hoflich C, Braun J, Halle E, Wolf T, Ruscher K, Victorov IV, Priller J, Dirnagl U, Volk HD & Meisel A (2003). Stroke‐induced immunodeficiency promotes spontaneous bacterial infections and is mediated by sympathetic activation reversal by poststroke T helper cell type 1‐like immunostimulation. J Exp Med 198, 725–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramer‐Quinn DS, Baker RA & Sanders VM (1997). Activated T helper 1 and T helper 2 cells differentially express the beta‐2‐adrenergic receptor: a mechanism for selective modulation of T helper 1 cell cytokine production. J Immunol 159, 4857–4867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramer‐Quinn DS, Swanson MA, Lee WT & Sanders VM (2000). Cytokine production by naive and primary effector CD4+ T cells exposed to norepinephrine. Brain Behav Immun 14, 239–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez‐Iturbe B, Pons H, Quiroz Y, Gordon K, Rincon J, Chavez M, Parra G, Herrera‐Acosta J, Gomez‐Garre D, Largo R, Egido J & Johnson RJ (2001). Mycophenolate mofetil prevents salt‐sensitive hypertension resulting from angiotensin II exposure. Kidney Int 59, 2222–2232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez‐Iturbe B, Quiroz Y, Herrera‐Acosta J, Johnson RJ & Pons HA (2002). The role of immune cells infiltrating the kidney in the pathogenesis of salt‐sensitive hypertension. J Hypertens Suppl 20, S9–S14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh MA, McMaster WG, Wu J, Norlander AE, Funt SA, Thabet SR, Kirabo A, Xiao L, Chen W, Itani HA, Michell D, Huan T, Zhang Y, Takaki S, Titze J, Levy D, Harrison DG & Madhur MS (2015). Lymphocyte adaptor protein LNK deficiency exacerbates hypertension and end‐organ inflammation. J Clin Invest 125, 1189–1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders VM, Baker RA, Ramer‐Quinn DS, Kasprowicz DJ, Fuchs BA & Street NE (1997). Differential expression of the beta2‐adrenergic receptor by Th1 and Th2 clones: implications for cytokine production and B cell help. J Immunol 158, 4200–4210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seravalle G, Mancia G & Grassi G (2014). Role of the sympathetic nervous system in hypertension and hypertension‐related cardiovascular disease. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev 21, 89–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi P, Diez‐Freire C, Jun JY, Qi Y, Katovich MJ, Li Q, Sriramula S, Francis J, Sumners C & Raizada MK (2010). Brain microglial cytokines in neurogenic hypertension. Hypertension 56, 297–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Pei W, Wu Y, Jing Z, Zhang J & Wang G (2004). Herpes simplex virus type 2 infection is a risk factor for hypertension. Hypertens Res 27, 541–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svendsen UG (1973). Increased cellular reaction to damage caused by angiotensin in arterioles of normal recipient rats after transfer of lymphocytes from hypertensive rats. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand A 81, 241–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svendsen UG (1978). The importance of thymus for hypertension and hypertensive vascular disease in rats and mice. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand Suppl, 1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson MA, Lee WT & Sanders VM (2001). IFN‐γ production by Th1 cells generated from naive CD4+ T cells exposed to norepinephrine. J Immunol 166, 232–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayanagi Y, Osawa S, Ikuma M, Takagaki K, Zhang J, Hamaya Y, Yamada T, Sugimoto M, Furuta T, Miyajima H & Sugimoto K (2012). Norepinephrine suppresses IFN‐γ and TNF‐α production by murine intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes via the β1 adrenoceptor. J Neuroimmunol 245, 66–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamir A & Isakov N (1991). Increased intracellular cyclic AMP levels block PKC‐mediated T cell activation by inhibition of c‐jun transcription. Immunol Lett 27, 95–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theuer J, Dechend R, Muller DN, Park JK, Fiebeler A, Barta P, Ganten D, Haller H, Dietz R & Luft FC (2002). Angiotensin II induced inflammation in the kidney and in the heart of double transgenic rats. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahdat K, Pourbehi MR, Ostovar A, Hadavand F, Bolkheir A, Assadi M, Farrokhnia M & Nabipour I (2013). Association of pathogen burden and hypertension: the Persian Gulf Healthy Heart Study. Am J Hypertens 26, 1140–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinh A, Chen W, Blinder Y, Weiss D, Taylor WR, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM, Harrison DG & Guzik TJ (2010). Inhibition and genetic ablation of the B7/CD28 T‐cell costimulation axis prevents experimental hypertension. Circulation 122, 2529–2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahle M, Hanefeld G, Brunn S, Straub RH, Wagner U, Krause A, Hantzschel H & Baerwald CG (2006). Failure of catecholamines to shift T‐cell cytokine responses toward a Th2 profile in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 8, R138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter U, Kolbaske S, Patejdl R, Steinhagen V, Abu‐Mugheisib M, Grossmann A, Zingler C & Benecke R (2013). Insular stroke is associated with acute sympathetic hyperactivation and immunodepression. Eur J Neurol 20, 153–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White FN & Grollman A (1964). Autoimmune factors associated with infarction of the kidney. Nephron 1, 93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiig H, Schroder A, Neuhofer W, Jantsch J, Kopp C, Karlsen TV, Boschmann M, Goss J, Bry M, Rakova N, Dahlmann A, Brenner S, Tenstad O, Nurmi H, Mervaala E, Wagner H, Beck FX, Muller DN, Kerjaschki D, Luft FC, Harrison DG, Alitalo K & Titze J (2013). Immune cells control skin lymphatic electrolyte homeostasis and blood pressure. J Clin Invest 123, 2803–2815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L, Kirabo A, Wu J, Saleh MA, Zhu L, Wang F, Takahashi T, Loperena R, Foss JD, Mernaugh RL, Chen W, Roberts J 3rd, Osborn JW, Itani HA & Harrison DG (2015). Renal denervation prevents immune cell activation and renal inflammation in angiotensin II‐induced hypertension. Circ Res 117, 547–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan FL & Zhang JH (2014). Role of the sympathetic nervous system and spleen in experimental stroke‐induced immunodepression. Med Sci Monit 20, 2489–2496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JD, Patel MB, Song YS, Griffiths R, Burchette J, Ruiz P, Sparks MA, Yan M, Howell DN, Gomez JA, Spurney RF, Coffman TM & Crowley SD (2012). A novel role for type 1 angiotensin receptors on T lymphocytes to limit target organ damage in hypertension. Circ Res 110, 1604–1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman MC, Lazartigues E, Lang JA, Sinnayah P, Ahmad IM, Spitz DR & Davisson RL (2002). Superoxide mediates the actions of angiotensin II in the central nervous system. Circ Res 91, 1038–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman MC, Lazartigues E, Sharma RV & Davisson RL (2004). Hypertension caused by angiotensin II infusion involves increased superoxide production in the central nervous system. Circ Res 95, 210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]