Abstract

DNA end resection is a key process in the cellular response to DNA double-strand break damage that is essential for genome maintenance and cell survival. Resection involves selective processing of 5′ ends of broken DNA to generate ssDNA overhangs, which in turn control both DNA repair and checkpoint signaling. DNA resection is the first step in homologous recombination-mediated repair and a prerequisite for the activation of the ataxia telangiectasia mutated and Rad3-related (ATR)-dependent checkpoint that coordinates repair with cell cycle progression and other cellular processes. Resection occurs in a cell cycle-dependent manner and is regulated by multiple factors to ensure an optimal amount of ssDNA required for proper repair and genome stability. Here, we review the latest findings on the molecular mechanisms and regulation of the DNA end resection process and their implications for cancer formation and treatment.

Keywords: DNA damage response, DNA end resection, MRN-CtIP, Exo1, cancer

Introduction

DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) are arguably the most toxic form of DNA damage, which, if unrepaired or improperly repaired, could cause genomic instability and a wide range of human diseases such as cancer, premature aging, immunodeficiency, neurodegeneration, and developmental disorders [1–4]. Eukaryotic cells are equipped with a conserved mechanism called DNA damage response (DDR) to detect, signal, and repair the damage by activating multiple repair and checkpoint pathways [5–7]. DSBs are repaired mainly by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homologous recombination (HR). NHEJ repairs the break through direct re-ligation of the broken DNA ends with no or limited end processing and thus is error-prone. By comparison, HR repairs the break in an error-free manner, and is initiated by nucleolytic processing of the 5′ ends of a DSB through a process called DNA end resection [8–16]. Resection occurs in 5′→3′ direction to generate 3′ ssDNA overhangs, which are initially bound by ssDNA-binding protein replication protein A (RPA) and then replaced by Rad51 during HR. The Rad51-ssDNA filament mediates homology search and strand invasion, followed by DNA synthesis, Holliday junction resolution, and DNA ligation to restore the integrity of the DNA structure [9,10,15,16]. The RPA-bound ssDNA structure also serves as the signal to activate the ATR checkpoint pathway that coordinates DNA repair with other cellular processes [17–19]. The generation of ssDNA by resection also indirectly inhibits NHEJ and attenuates the activation of the ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) checkpoint pathway [8,9,11,20,21]. Thus, resection is considered to be the major event in the DDR that dictates the pathway choice of both DNA repair and checkpoint signaling (Fig. 1). While DSB repair by NHEJ can occur at any time during the cell cycle, HR occurs primarily in S and G2 phases when sister chromatids are available [9–11,22–25]. This cell cycle control of HR is in part mediated by the regulation of DNA end resection by cyclin dependent kinase (CDK) activity [26–29]. Resection is apparently also regulated by the checkpoint response to prevent deleterious consequences resulted from excessive resection [30–35]. Besides its role in HR, resection also plays a role in the maintenance of 3′ overhangs at telomeres and repair of uncapped telomeres at the end of chromosomes [36–39]. Likewise, resection also occurs at ssDNA-dsDNA junctions of stalled replication forks and at dsDNA ends of reversed forks, and is important for fork repair and restart [40–45]. However, the detailed mechanisms of end resection in these contexts are much less understood. Genetic mutations in resection factors are associated with multiple genetic disorders and predisposition to cancer and premature aging [1,2,4]. On the other hand, DNA end resection could also be a suitable target for cancer therapy because rapidly dividing cancer cells rely heavily on HR and the ATR checkpoint for growth and survival. In this review, we discuss our current understanding of the mechanisms and regulation of the DNA end resection process and their potential implications for cancer formation and treatment, focusing mainly on vertebrate systems.

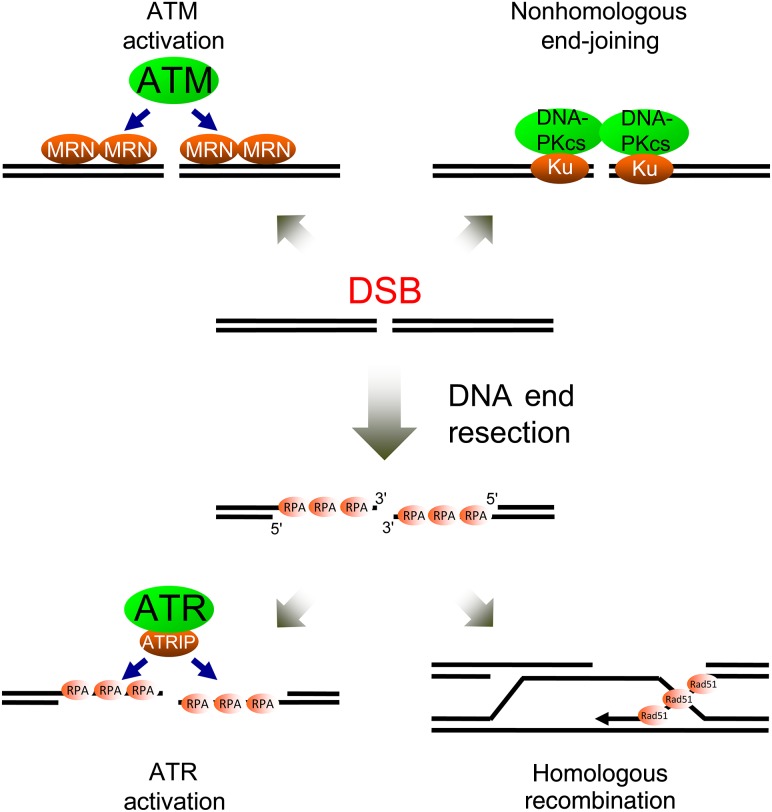

Figure 1.

DNA end resection dictates the pathway choice for both DNA repair and checkpoint response DSBs can be repaired by NHEJ or by HR that requires 3′ ssDNA generated by end resection. Checkpoint kinase ATM is activated on the dsDNA flanking the break, whereas ATR is activated on the ssDNA structure generated by resection. Thus, DNA end resection promotes HR and ATR activation and attenuates NHEJ and ATM activation.

Key Steps and Core Factors of DNA End Resection

Initiation of resection by MRN and CtIP

Studies in yeast, human cells, and in vitro reconstituted systems with purified proteins suggest that DSB end resection is initiated by a concerted action of MRN (Mre11-Rad50-NBS1) [MRX (Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2) in budding yeast] together with CtIP (Sae2 in budding yeast and Ctp1 in fission yeast) [46–51] (Fig. 2). MRN complex, which is among the first set of proteins to localize to sites of DNA damage, has a high affinity for DSB ends and plays a central role in sensing breaks in chromatin [52–54]. MRN promotes the damage recruitment of the ATM checkpoint kinase and its subsequent activation [55]. They also promote the recruitment of CtIP to sites of damage [51]. The NBS1 subunit of the MRN complex plays a key role in coupling these events through its direct interactions with Mre11, CtIP, and ATM [51,55–59]. Rad50 is an ATPase that maintains the conformation of MRN complex and promotes DNA binding of the complex, as well as DNA resection and ATM activation by the complex [60–63]. The Mre11 subunit possesses the catalytic function of MRN complex in resection and has both 5′ flap endonuclease activity and 3′→5′ exonuclease activity. Its endonuclease function is believed to initiate resection by internal cleavage of the 5′ strand to generate oligonucleotides that will be released, while the exonuclease activity processes the resulting 3′ ends on the DNA [64–71]. While MRN is necessary, the complex by itself is not sufficient to initiate resection. CtIP is also required for the initiation of DNA end resection by MRN complex [50,51,72–74]. In vitro studies with purified yeast MRX and Sae2 proteins suggest that MRN-CtIP is a minimal system for resection initiation [46]. CtIP interacts directly with NBS1 and promotes the endonuclease activity of Mre11 at the DSB ends [50,51]. Both CtIP and Sae2 have also been shown to contain an endonuclease activity [75,76]. While there is no direct evidence for the nuclease activity of CtIP or Sae2 in the resection initiation at ‘clean’ DSBs, they have been suggested to function to remove secondary DNA structures on the 5′ strand DNA at DSB ends [75–77]. Resection initiation by MRN-CtIP is especially important when the ends are bound by chemical or protein adducts that prevent exonucleases from binding and processing them [69,70,78,79]. A prominent example of such breaks is the DSBs generated during meiotic recombination, which are covalently linked to the Spo11 protein. Resection of these Spo11-blocked ends in yeast is initiated by the endonucleolytic activity of MRX-Sae2 to initiate the resection before further processing [69,70]. For DSBs that are free of chemical or protein adducts, MRX-Sae2 function is dispensable for end resection [47,71,80]. In addition to end cleavage, studies in yeast suggest that MRX-Sae2 or MRN-Ctp1 plays a role in removing the NHEJ factor Ku from the DNA ends to promote the binding of nucleases Exo1 and Dna2 that mediate resection extension [81–83]. Moreover, MRN-CtIP in human cells also provide structural and catalytic support to recruit Exo1 and Dna2 to the damage site to extend the resection [82–87].

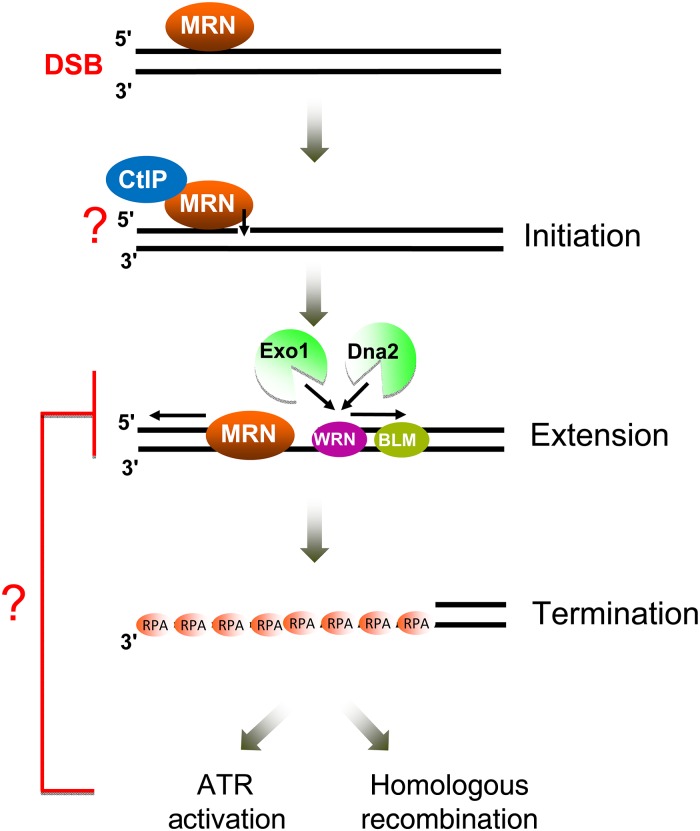

Figure 2.

Key steps and core factors of DNA end resection Resection is initiated on the 5′ strand of the DNA by the endocleavage activity of MRN-CtIP and extended by Exo1 and Dna2 in two parallel pathways. The underlying mechanism for the 5′ strand selectivity of MRN-CtIP in resection initiation is still not completely understood. The ssDNA generated from resection is bound and protected by RPA which promotes ATR activation and HR when replaced by Rad51. Precisely how resection is terminated remains unclear, but the ATR checkpoint pathway may help terminate resection via a feedback loop mechanism.

Extension of resection by Exo1 and Dna2

Limited resection by MRN-CtIP alone could lead to DNA repair by a less common and highly error-prone mechanism called microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ), which involves the alignment of short ssDNA overhangs before ligation [9,88–90]. While limited resection by MRX-Sae2 in yeast has been shown to be sufficient for HR repair, extended resection appears to be required to avoid MMEJ and promote HR [9,71,90–92]. Resection extension is carried out by Exo1 and Dna2 in two parallel pathways, which can produce ssDNA of several kilobases long [47,71,93,94] (Fig. 2). Exo1 is a member of the RAD2 family of nucleases that possesses 5′→3′ dsDNA exonuclease and 5′-flap endonuclease activities, and plays a role in a plethora of biological processes including DNA replication, recombination, repair, checkpoint activation, and telomere maintenance [95–103]. The resection function of Exo1 is positively regulated by MRN, Bloom syndrome RecQ-like helicase (BLM), RPA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), and 9-1-1 [87,103–106]. MRN, PCNA, and likely 9-1-1 complex act to promote the processivity of Exo1 [87,104–106]. It has been reported that CtIP promotes the loading of Exo1 to the damage site but negatively regulates Exo1 nuclease activity [107]. However, CtIP has also been shown to be required for extensive resection and checkpoint maintenance, although the detailed mechanism remains to be determined [108].

Another major resection extension factor is the helicase/endonuclease Dna2, which is well known for its role in Okazaki fragment maturation and G-quadruplex DNA processing during DNA replication [109–113]. During DNA end resection, Dna2 works together with Sgs1-Top3-Rmi1 complex in yeast and Sgs1 ortholog BLM in cultured human cells [71,85–87,114]. Studies in Xenopus egg extracts as well as human cells show that another RecQ family of helicase Werner syndrome RecQ-like helicase (WRN) also promotes resection by unwinding the DNA ends and making it accessible for Dna2 [115–119]. Although Dna2 functions as both a helicase and a nuclease, only the nuclease activity is essential for the extension of DNA end resection [87,120,121]. The long stretch of ssDNA generated by Exo1 and Dna2 serves as the substrate for HR, and in the meantime prevents repair by NHEJ or MMEJ [9,92]. The ssDNA-binding protein RPA promotes resection extension by enhancing the nuclease activity of Dna2 on the 5′ strand and by suppressing the inhibitory effects of the 3′ ssDNA resection product on Exo1 [85–87,92,117,118,122–124].

Termination of resection

Although ssDNA generated by resection is essential for ATR checkpoint and HR, uncontrolled excessive resection could be deleterious to genome integrity, as ssDNA is more prone to degradation that causes loss of genetic information. Excessive ssDNA generated by resection may also exhaust the RPA pool in cells, leading to unprotected ssDNA and genomic instability [123,125]. Therefore, it is expected that when the length of ssDNA reaches a certain threshold, resection activities would stop processing the DNA ends. However, the control of the timing and the mechanism of resection termination are still unclear. Studies in yeast and human cells both suggest that the nuclease activity of major resection factor Exo1 is inhibited in a checkpoint-dependent manner. In yeast, Exo1 nuclease activity is inhibited by both Mec1 and Rad53 at uncapped telomeres [30]. Phosphorylation of Exo1 by Rad53 in yeast appears to inhibit its activity in processing DSB ends, unprotected telomeres and stalled replication forks. In human cells, direct phosphorylation of Exo1 by ATR leads to Exo1 degradation during replication stress [31–33,126]. It is possible that Exo1 is also negatively regulated by the ATR checkpoint response during DNA end resection. Another study shows that ATM phosphorylates Exo1 and limits its activity after RPA is bound to ssDNA [34]. Together, these observations suggest that checkpoint-mediated phosphorylation of Exo1 inhibits its activity to terminate the resection. Interestingly, Exo1 interacts with phospho-peptide binding proteins 14-3-3s, and this interaction inhibits its damage recruitment and subsequent DNA resection [127–129]. Thus, it is plausible that phosphorylation of Exo1 by ATM, ATR, or their downstream kinases promotes the interaction of Exo1 with 14-3-3s, preventing its association with DNA damage, thereby promoting resection termination (Fig. 2). Interestingly, Durocher and colleagues have recently proposed another negative feedback mechanism for resection termination in which the recruitment of DNA helicase HELB by RPA to ssDNA inhibits the nuclease activities of Exo1 and BLM-Dna2, although the detailed biochemical mechanism of this inhibition remains to be defined [130]. Another possible mechanism for resection termination is the second end capture during HR, which may prevent further resection by annealing the complimentary strands and formation of double Holliday junction [131–134]. Recent studies have also shown that Dna2 is inhibited by fanconi anemia complementation group 2 (FANCD2) in human cells and Pxd1 in fission yeast [135,136], which could be the mechanisms to terminate Dna2-mediated DNA end resection.

RPA selects 5′ strand for resection and protects 3′ strand resection product

DSB resection occurs in the 5′→3′ direction, but what determines this directionality for the cleavage of the 5′ ends during resection initiation is still a mystery. An in vitro study by Petr Cejka and colleagues shows that MRX together with Sae2 selectively cleave the 5′ strand of a linear dsDNA substrate to initiate the resection, although the detailed mechanism for this strand selectivity in this ‘minimal’ resection initiation system remains to be determined [46]. Nevertheless, the mechanism for the strand selectivity during resection extension is better understood. Exo1 acts as a 5′→3′ exonuclease and thus has intrinsic polarity [95–98]. RPA plays a key role in selecting the 5′ strand for processing by Dna2, which functions as a flap endonuclease in resection [85–87,120]. Initial unwinding of the broken DNA ends by helicase BLM or WRN generates both 5′ and 3′ ssDNA strands. In vitro studies using purified proteins show that RPA binds to both strands but allows resection to occur only on the 5′ strand of the DNA [85–87,120]. A recent structural study of Dna2-ssDNA-RPA complex and in vitro nuclease assays using mouse Dna2 shows that Dna2 physically interacts with RPA bound to both strands but can only displace RPA from the 5′ strand and hence the resection occurs only on the 5′ strand [120]. Studies in Xenopus egg extracts also show that RPA interacts with both WRN and Dna2 to promote 3′→5′ helicase activity of WRN and 5′→3′ nuclease activity of Dna2 [117,118]. In addition to its role in directing 5′→3′ resection, RPA binds promptly to the newly generated 3′ ssDNA and protects the resection product [85–87,92,118,120,123,124]. Functional disruption of RPA in yeast not only abrogates resection extension, but also causes formation of hairpin structures on the short 3′ ssDNA generated by MRX-Sae2, which can be further processed, resulting in genomic instability [123]. Binding RPA to 3′ ssDNA overhangs also suppresses DNA repair by MMEJ [92].

Regulation of DNA End Resection

Either insufficient or excessive resection could compromise genome stability and cellular viability. While insufficient resection impairs the process of HR and ATR activation, over-resection could cause persistent checkpoint activation, loss of genetic information, and even cell death [123,137]. In fact, accumulation of ssDNA is a major source of mutational load and genomic rearrangements in different forms of cancer [138–140]. Hence, resection must be properly controlled to prevent under- or over-resection. To avoid HR in G1 phase of the cell cycle, DNA resection is also regulated by the cell cycle [9,11,13,23,25,74]. While the key steps of resection and core factors have been widely studied, many questions remain open as to precisely how the overall extent of resection is controlled. Below we will discuss the regulation of the resection process by the cell cycle, checkpoint response, and other factors.

Cell cycle regulation of resection

In G1 phase of the cell cycle, DSBs are repaired mainly by NHEJ or MMEJ, two pathways that require no or little end resection [8,9,74,89,90,141]. DNA end resection in G1 phase in general is suppressed by low activity of CDKs and higher activity of NHEJ factors [22,28]. Ku70-Ku80 protein heterodimer, a major NHEJ factor, loads onto DSB ends during G1 to promote repair by NHEJ while indirectly inhibiting DNA end resection [142–146]. Nevertheless, limited end processing is still possible during G1 due to the activities of MRN and CtIP [147,148]. However, this limited resection by MRN-CtIP during G1 could be mechanistically different from their resection function during S and G2 phases. Suppression of DNA end resection in G1 phase is important as it prevents HR between homologous chromosomes that can lead to loss of heterozygosity.

During S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, DSBs can be repaired by HR that requires more extensive resection to generate a significant length of ssDNA for Rad51 binding and homology search on a sister chromatid [9,14–16]. This increased resection results from the high level of CDK activity, which promotes the functions of the core resection factors including MRN, CtIP, Exo1, and Dna2 [26–29,149–156]. The NBS1 subunit of the MRN complex is phosphorylated by CDKs at S432 in S, G2, and M phases (but not in G1), which is important for DNA end resection [149,150]. Mre11 interacts directly with CDK2 and promotes phosphorylation of CtIP/Sae2 by CDK2, which is also crucial for resection in S and G2 phases [147,151–153]. In budding yeast, Sae2 is phosphorylated at S267 by Cdc28 (CDK1) and mutation of this residue to alanine inhibits DNA resection in vivo [152]. In human CtIP, the CDK phosphorylation sites S327 and T847 have been reported to be important for resection and subsequent HR in S and G2 phases of the cell cycle [153,154]. Phosphorylation of CtIP by CDK2 promotes resection in part through increased damage recruitment of CtIP and association with MRN complex [72,153]. CDKs also regulate resection extension by direct phosphorylation of Exo1 and Dna2, which also promotes their damage recruitment [155,156].

Compared to S and G2 phases, less is understood about DSB resection during M phase. The highly condensed nature of chromosomes in M phase may preclude the accessibility of repair factors to DSBs in M phase, thus cells could just exit mitosis with the DSBs that will be repaired by NHEJ in the next G1 phase [157,158]. A recent study in Xenopus egg extracts and cultured human cells shows that limited resection still occurs at DSBs during M phase by the activity of MRN and CtIP [159]. However, the high CDK1 activity also prevents the loading of ATR and Rad51 to the RPA-coated ssDNA. As a result, ATR checkpoint and HR are not activated in M phase [157,159].

Checkpoint regulation of resection

DNA end resection is also regulated by checkpoint kinases. Mass spectrometric studies have shown that hundreds of DDR proteins including major resection factors are phosphorylated by ATM/ATR after DNA damage [160,161]. ATM promotes the damage recruitment of CtIP in human cells and Xenopus egg extracts [51]. CtIP phosphorylation by ATR on T818 in Xenopus egg extracts also promotes its damage recruitment and resection activity [162]. In yeast, Sae2 is phosphorylated by both Mec1 (ATR) and Tel1 (ATM), which promotes its function in DNA end processing [163,164].

Interestingly, checkpoint kinases not only promote resection but also prevent unscheduled and over-resection by nucleases. Consistently, Mec1 deletion in yeast causes accelerated rate of DSB resection [21]. A study in Xenopus egg extracts showed that phosphorylation of Mre11 at SQ/TQ sites facilitates MRN complex dissociation from the damage site [165], which could be dependent on ATM/ATR to down-regulate Mre11 activity after initiation of resection. In human cells, ATM phosphorylates Mre11 on S676 and S678, which promotes Exo1 phosphorylation by ATM that attenuates its activity [34,35]. Mec1 and its downstream kinase Rad53 in budding yeast inhibit Exo1 activity at unprotected telomeres and prevent the accumulation of ssDNA [30]. Rad53-mediated phosphorylation of Exo1 attenuates its nuclease function and prevents uncontrolled resection at DSBs, telomeres, and stalled replication forks [32,33]. In human cells, ATR phosphorylates Exo1 in response to replication stress, which promotes Exo1 degradation to prevent the aberrant processing of replication forks [31]. Yeast Dna2 has also been suggested to be phosphorylated by checkpoint kinase Mec1, although whether this phosphorylation suppresses Dna2 resection activity remains to be determined [155]. Overall, it appears that the checkpoint kinases play a positive role in an early stage of resection and a negative role in a late stage of resection.

Regulation of resection by 53BP1 and BRCA1

The tumor suppressor BRCA1 promotes DNA end resection and is important for HR [72,166–169]. The HR defects of BRCA1-deficient cells are synthetic lethal with inhibitors of PARP1 that is involved in base excision repair [170,171]. Interestingly, the HR defects and cellular hyper-sensitivity to PARP1 inhibitors of BRCA1-deficient cells can be rescued by inactivation of 53BP1, which is important for NHEJ [168,172–177]. While the detailed mechanisms of their respective functions in HR and NHEJ are still incompletely understood, BRCA1 and 53BP1 act antagonistically to regulate DNA end resection. 53BP1 inhibits DNA end resection through its associated factors Rap1 interacting factor 1 homolog (RIF1) and pax transactivation domain interacting protein (PTIP) [178–183]. RIF1 inhibits BRCA1 damage recruitment during G1, inhibits resection, and hence promotes repair by NHEJ [179,180,183]. During S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, BRCA1 together with CtIP inhibits the damage recruitment of RIF1, allowing for resection and repair by HR [147,167,174,184]. BRCA1 also recruits the E3 ubiquitin ligase UHRF1 to the damage site where it ubiquitinates and removes RIF1 from the damage site, thereby promoting resection and HR [185]. While the mechanism of how BRCA1 inhibits PTIP is unclear, it may involve the disruption of its interaction with 53BP1 and damage association [174,178,182]. The striking functional relationship between BRCA1 and 53BP1 underscores the delicate balance between the HR and NHEJ pathways and the importance of proper regulation of the DNA resection process.

Mechanisms that prevent over-resection

DNA end resection must be properly controlled to prevent over-resection, as excessive ssDNA could cause cell death or genomic instability. Over-resection may result from unscheduled initiation, uncontrolled extension, or untimely termination. The function of Exo1 in resection is restrained by 14-3-3 proteins, which limit the damage recruitment of Exo1 by suppressing the binding of Exo1 to poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR) and PCNA, both of which promote Exo1’s damage association [104,127,186] (Fig. 3). Disruption of the Exo1-14-3-3 interaction causes over-resection and increased sensitivity to DNA damage [127]. Exo1 activity in DSB resection may also be regulated by post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation, SUMOylation, and ubiquitination. In budding yeast, Exo1 is phosphorylated by Rad53 in response to DSBs, telomere uncapping, and replication stress, which inhibits its nuclease activity [32,33]. In human cells, Exo1 is phosphorylated by ATR and SUMOylated by UBC9-PIAS1/PIAS4 in response to stalled replication, which induces its ubiquitination and degradation in a proteasome-dependent manner [31,126,187]. It is possible that similar mechanisms exist to limit Exo1 activity during resection of DSBs. Recent studies have shown that Dna2 resection activity is restrained by FANCD2 in human cells and Pxd1 in fission yeast, although the detailed mechanisms remain to be defined [135,136]. Studies in Xenopus egg extracts and human cells suggest that ATM-mediated phosphorylation of Mre11 inhibits its damage association as well as Exo1 nuclease activity preventing over-resection [35,165]. The function of CtIP in resection is negatively regulated by phosphorylation-specific prolyl-isomerase PIN1, which binds to CtIP, and promotes its isomerization and subsequent ubiquitination and degradation [188]. It is expected that these regulatory mechanisms function collectively to prevent uncontrolled excessive resection.

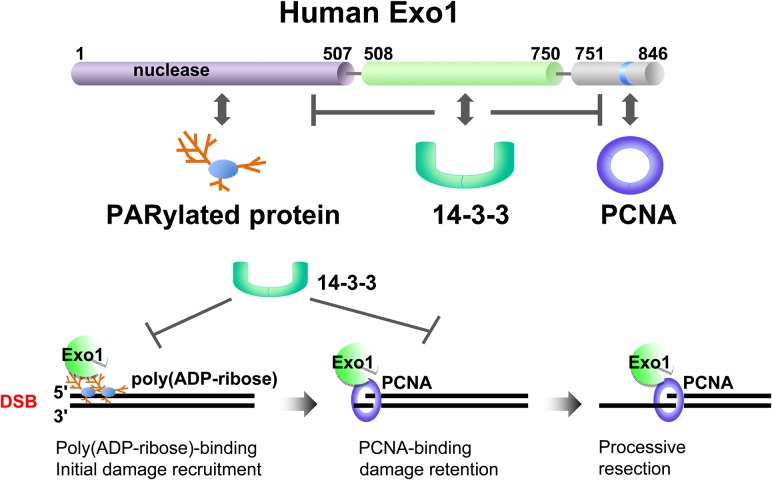

Figure 3.

Human Exo1 is regulated by PCNA, poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation, and 14-3-3s The damage recruitment and resection activity of Exo1 are controlled by three sets of factors that directly interact with different domains in Exo1. PARylated proteins bind to the N-terminus of Exo1 and promote the initial damage recruitment of Exo1. PCNA binds to the PCNA-Interacting Protein box in the C-terminus of Exo1 and promotes the damage retention and processivity of Exo1. 14-3-3 Proteins interact with the central domain of Exo1 and inhibit its damage recruitment by suppressing the interactions of Exo1 with PARylated proteins and PCNA. These coordinated regulations of Exo1 by multiple factors with opposing activities ensure a highly orchestrated resection process and a proper level of ssDNA at DSBs.

Other regulatory factors

In addition to the core factors described above, recent studies in multiple organisms have identified many other factors such as EXD2, PCNA, 9-1-1, PAR, lysine deacetylase SIRT6, chromatin-binding protein LEDGF/p75, chromatin remodelers SMARCAD1/Fun30 and SRCAP, ssDNA-binding protein SOSS1, and RNA-binding hnRNPU-like proteins in DNA end resection [104–106,186,189–197]. These factors promote resection by promoting the damage recruitment of core resection factors, remodeling the chromatin structure at damage sites or enhancing activities of resection nucleases. The existence of these many regulatory factors further demonstrates that DNA resection is a highly orchestrated process that involves sophisticated coordination of nuclease and helicase activities.

DNA Resection at Telomeres, Stalled Replication Forks, and Heterochromatin

The 3′ ssDNA overhangs at telomeres are essential for telomerase binding and telomere maintenance [198–200]. Replication of lagging strand DNA naturally generates ssDNA overhangs at telomeres in a sister chromatid. However, the leading strand is replicated completely, generating a blunt end that requires resection to produce a 3′ ssDNA overhang [198–200]. This resection is carried out by an exonuclease called Apollo, which acts immediately after the completion of replication [201,202]. Extensive resection by Apollo is inhibited by the binding of Pot1b to the ssDNA [201]. In yeast, Dna2 has also been suggested to be involved in limited processing of the 5′ strand to maintain the telomere length and telomerase binding [203,204]. While 5′ strand resection is important for telomere maintenance, over-resection could lead to telomere shortening, senescence, and other deleterious consequences [198]. Indeed, studies in yeast have shown that when the telomeric ends are not protected by capping proteins, Exo1 together with the Pif1 helicase could resect the ends of replicated DNA of both leading and lagging strands and initiates a protracted checkpoint response [205,206]. To avoid this, it has been shown in human cells that resection of telomere ends by Exo1 is inhibited by Pot1b and RIF1 [176,181,201,202].

DNA resection is also highly regulated in DNA replication. Studies in yeast and human cells suggest that Exo1 degrades stalled forks and that checkpoint-dependent phosphorylation of Exo1 inhibits this activity [31–33]. Mre11 has been suggested to play a major role in the processing and restart of stalled replication forks [43,207]. However, uncontrolled resection by Mre11 could also lead to degradation of stalled forks, leading to fork collapse. Indeed, it has been shown that BRCA2 and PARP1 inhibit Mre11 nuclease activity to prevent fork degradation [43,208]. WRN helicase also plays a major role in coordinating fork processing and restart by preventing unscheduled nascent DNA degradation by Mre11 and Exo1 [209,210]. In Xenopus egg extracts, Rad51 binds to the newly synthesized DNA during replication and protects it from degradation by Mre11 [211]. In yeast and human cells, Dna2-mediated end processing is important for the restart of stalled or reversed replication forks [44,45,212]. However, upon replication fork stalling caused by interstrand crosslink, Dna2 activity is restrained by FANCD2 to prevent uncontrolled resection [135].

To date, little is known about the mechanisms and regulation of DNA end resection in heterochromatin. Recent studies in Drosophila melanogaster suggest that resection occurs efficiently in heterochromatin; however, DSBs are not repaired by HR until the DNA ends relocate outside of the heterochromatin domain [213,214]. The relocalization of DSB is facilitated by resection and ATR [213]. Counter-intuitively, resection of DSBs in heterochromatin and subsequent loading of ATR interacting protein (ATRIP) and TopBP1 required for ATR activation appear to occur in a faster kinetics than in euchromatin, suggesting that resection is regulated differently in these two types of chromatin domains [213–215].

Relevance of DNA End Resection for Cancer Formation and Therapy

DNA end resection is essential for ATR checkpoint activation and HR, both of which play a critical role in genome maintenance and tumor suppression [1–4,7,10,18]. Genetic knockout of the major resection factors Mre11, Rad50, NBS1, CtIP, and Dna2 in mice is embryonically lethal, and their deficiencies cause hypersensitive to DNA damaging agents [64,112,216–218]. Exo1 knockout in mice leads to meiotic defects and cancer susceptibility [219]. Mutations in Mre11, NBS1, Rad50, BLM, and WRN are causes of genetic diseases AT-like Disorder, Nijmegen Breakage Syndrome, NBS-like Disorder, Bloom Syndrome, and Werner Syndrome, respectively, all of which are associated with cancer predispositions [3,220–224]. These findings further highlight the importance of DNA end resection in genome protection and tumor suppression. Paradoxically, DNA end resection may also be targeted for cancer therapy. The synthetic lethal relationship between PARP inhibition and HR deficiency suggests that combining inhibitors of PARPs with that of resection activities may be effective in cancer treatment [170,171]. Moreover, over-resection (e.g. by disrupting Exo1-14-3-3 interaction) increases cellular sensitivity to DNA damage, and thus may also be exploited for cancer treatment [127].

Conclusions and Perspective

DNA end resection is a key process in the DDR that controls both DNA repair and checkpoint response. Resection is initiated by an endocleavage step that is carried out by the MRN complex in collaboration with CtIP. Extended resection is mediated by two parallel pathways involving the Exo1 and Dna2 nucleases, respectively. The resection process is tightly regulated by multiple mechanisms and accessory factors to ensure proper repair at DSBs, telomere, replication forks, and heterochromatin. The DNA resection process is highly relevant to tumorigenesis and may be targeted for cancer therapy. Understanding the detailed mechanisms and regulation of DNA resection is the key to designing more efficient cancer therapeutics. Future work is needed to address many outstanding questions in the field, e.g. what determines the strand specificity during resection initiation? How do MRN and CtIP cooperate to initiate DNA resection? Are there any mechanistic differences in the initiation of resection of DNA ends with different structures? Do Exo1 and Dna2 pathways function redundantly at telomeres and stalled/collapsed replication forks? How is resection terminated? How is over-resection avoided? What does control the extent of DNA resection? How is resection regulated in heterochromatin? Can DNA end resection be exploited for cancer therapy, and if so, which resection activities can be targeted? The next few years will see major advances in addressing these important questions.

Acknowledgment

We apologize to colleagues whose work is not cited due to space limitation.

Funding

The work was supported by the grants from the National Institutes of Health (No. R01GM098535) and the American Cancer Society Research Scholar Grant (No. RSG-13-212-01-DMC).

References

- 1.Aguilera A, Gómez-González B.. Genome instability: a mechanistic view of its causes and consequences. Nat Rev Genet 2008, 9: 204–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKinnon PJ, Caldecott KW.. DNA strand break repair and human genetic disease. Annu Rev Genom Hum Genet 2007, 8: 37–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson LH, Schild D.. Recombinational DNA repair and human diseases. Mutat Res 2002, 509: 49–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackson S, Bartek J.. The DNA-damage response in human biology and disease. Nature 2009, 461: 1071–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciccia A, Elledge SJ.. The DNA damage response: making it safe to play with knives. Mol Cell 2010, 40: 179–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bakkenist CJ, Kastan MB.. Initiating cellular stress responses. Cell 2004, 118: 9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kastan MB, Bartek J.. Cell-cycle checkpoints and cancer. Nature 2004, 432: 316–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lieber MR. The mechanism of double-strand DNA break repair by the nonhomologous DNA end-joining pathway. Annu Rev Biochem 2010, 79: 181–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Symington LS, Gautier J.. Double-strand break end resection and repair pathway choice. Annu Rev Genet 2011, 45: 247–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aparicio T, Baer R, Gautier J.. DNA double-strand break repair pathway choice and cancer. DNA Repair (Amst) 2014, 19: 169–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kass EM, Jasin M.. Collaboration and competition between DNA double-strand break repair pathways. FEBS Lett 2010, 584: 3703–3708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernstein KA, Rothstein R.. At loose ends: resecting a double-strand break. Cell 2009, 137: 807–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huertas P. DNA resection in eukaryotes: deciding how to fix the break. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2010, 17: 11–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cejka P. DNA end resection: nucleases team up with the right partners to initiate homologous recombination. J Biol Chem 2015, 290: 22931–22938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moynahan ME, Jasin M.. Mitotic homologous recombination maintains genomic stability and suppresses tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2010, 11: 196–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sung P, Klein H.. Mechanism of homologous recombination: mediators and helicases take on regulatory functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2006, 7: 739–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zou L, Elledge SJ.. Sensing DNA damage through ATRIP recognition of RPA-ssDNA complexes. Science 2003, 300: 1542–1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cimprich KA, Cortez D.. ATR: an essential regulator of genome integrity. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2008, 9: 616–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jazayeri A, Falck J, Lukas C, Bartek J, Smith GCM, Lukas J, Jackson SP.. ATM- and cell cycle-dependent regulation of ATR in response to DNA double-strand breaks. Nat Cell Biol 2006, 8: 37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shiotani B, Zou L.. Single-stranded DNA orchestrates an ATM-to-ATR switch at DNA breaks. Mol Cell 2009, 33: 547–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clerici M, Trovesi C, Galbiati A, Lucchini G, Longhese MP.. Mec1/ATR regulates the generation of single-stranded DNA that attenuates Tel1/ATM signaling at DNA ends. EMBO J 2014, 33: 198–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Branzei D, Foiani M.. Regulation of DNA repair throughout the cell cycle. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2008, 9: 297–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shrivastav M, De Haro LP, Nickoloff JA.. Regulation of DNA double-strand break repair pathway choice. Cell Res 2008, 18: 134–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kadyk LC, Hartwell LH.. Sister chromatids are preferred over homologs as substrates for recombinational repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 1992, 132: 387–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orthwein A, Noordermeer SM, Wilson MD, Landry S, Enchev RI, Sherker A, Munro M, et al. A mechanism for the suppression of homologous recombination in G1 cells. Nature 2015, 528: 422–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferretti LP, Lafranchi L, Sartori AA.. Controlling DNA-end resection: a new task for CDKs. Front Genet 2013, 4: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scully R, Xie A.. In my end is my beginning: control of end resection and DSBR pathway ‘choice’ by cyclin-dependent kinases. Oncogene 2005, 24: 2871–2876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aylon Y, Liefshitz B, Kupiec M.. The CDK regulates repair of double-strand breaks by homologous recombination during the cell cycle. EMBO J 2004, 23: 4868–4875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ira G, Pellicioli A, Balijja A, Wang X, Fiorani S, Carotenuto W, Liberi G, et al. DNA end resection, homologous recombination and DNA damage checkpoint activation require CDK1. Nature 2004, 431: 1011–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jia X, Weinert T, Lydall D.. Mec1 and Rad53 inhibit formation of single-stranded DNA at telomeres of Saccharomyces cerevisiae cdc13-1 mutants. Genetics 2004, 166: 753–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.El-Shemerly M, Hess D, Pyakurel AK, Moselhy S, Ferrari S.. ATR-dependent pathways control hEXO1 stability in response to stalled forks. Nucleic Acids Res 2008, 36: 511–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morin I, Ngo H-P, Greenall A, Zubko MK, Morrice N, Lydall D.. Checkpoint-dependent phosphorylation of Exo1 modulates the DNA damage response. EMBO J 2008, 27: 2400–2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cotta-Ramusino C, Fachinetti D, Lucca C, Doksani Y, Lopes M, Sogo J, Foiani M.. Exo1 processes stalled replication forks and counteracts fork reversal in checkpoint-defective cells. Mol Cell 2005, 17: 153–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bolderson E, Tomimatsu N, Richard DJ, Boucher D, Kumar R, Pandita TK, Burma S, et al. Phosphorylation of Exo1 modulates homologous recombination repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Nucleic Acids Res 2010, 38: 1821–1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kijas AW, Lim YC, Bolderson E, Cerosaletti K, Gatei M, Jakob B, Tobias F, et al. ATM-dependent phosphorylation of MRE11 controls extent of resection during homology directed repair by signalling through Exonuclease 1. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43: 8352–8367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Longhese MP, Bonetti D, Manfrini N, Clerici M.. Mechanisms and regulation of DNA end resection. EMBO J 2010, 29: 2864–2874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Longhese MP. DNA damage response at functional and dysfunctional telomeres. Genes Dev 2008, 22: 125–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dewar JM, Lydall D.. Similarities and differences between ‘uncapped’ telomeres and DNA double-strand breaks. Chromosoma 2012, 121: 117–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wellinger RJ. When the caps fall off: responses to telomere uncapping in yeast. FEBS Lett 2010, 584: 3734–3740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Petermann E, Helleday T.. Pathways of mammalian replication fork restart. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2010, 11: 683–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carr AM, Lambert S.. Replication stress-induced genome instability: the dark side of replication maintenance by homologous recombination. J Mol Biol 2013, 425: 4733–4744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Atkinson J, McGlynn P.. Replication fork reversal and the maintenance of genome stability. Nucleic Acids Res 2009, 37: 3475–3492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bryant HE, Petermann E, Schultz N, Jemth A, Loseva O, Issaeva N, Johansson F, et al. PARP is activated at stalled forks to mediate Mre11-dependent replication restart and recombination. EMBO J 2009, 28: 2601–2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thangavel S, Berti M, Levikova M, Pinto C, Gomathinayagam S, Vujanovic M, Zellweger R, et al. DNA2 drives processing and restart of reversed replication forks in human cells. J Cell Biol 2015, 208: 545–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peng G, Dai H, Zhang W, Hsieh H-J, Pan M-R, Park Y-Y, Tsai RYL, et al. Human nuclease/helicase DNA2 alleviates replication stress by promoting DNA end resection. Cancer Res 2012, 72: 2802–2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cannavo E, Cejka P.. Sae2 promotes dsDNA endonuclease activity within Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2 to resect DNA breaks. Nature 2014, 514: 122–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mimitou EP, Symington LS.. Sae2, Exo1 and Sgs1 collaborate in DNA double-strand break processing. Nature 2008, 455: 770–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Limbo O, Chahwan C, Yamada Y, de Bruin RAM, Wittenberg C, Russell P.. Ctp1 is a cell-cycle-regulated protein that functions with Mre11 complex to control double-strand break repair by homologous recombination. Mol Cell 2007, 28: 134–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Takeda S, Nakamura K, Taniguchi Y, Paull TT.. Ctp1/CtIP and the MRN complex collaborate in the initial steps of homologous recombination. Mol Cell 2007, 28: 351–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sartori AA, Lukas C, Coates J, Mistrik M, Fu S, Bartek J, Baer R, et al. Human CtIP promotes DNA end resection. Nature 2007, 450: 509–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.You Z, Shi LZ, Zhu Q, Wu P, Zhang YW, Basilio A, Tonnu N, et al. CtIP links DNA double-strand break sensing to resection. Mol Cell 2009, 36: 954–969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Petrini J. The cellular response to DNA double-strand breaks: defining the sensors and mediators. Trends Cell Biol 2003, 13: 458–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rupnik A, Lowndes NF, Grenon M.. MRN and the race to the break. Chromosoma 2010, 119: 115–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kanaar R, Wyman C.. DNA repair by the MRN complex: break it to make it. Cell 2008, 135: 14–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.You Z, Chahwan C, Bailis J, Hunter T, Russell P.. ATM activation and its recruitment to damaged DNA require binding to the C terminus of Nbs1. Mol Cell Biol 2005, 25: 5363–5379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Williams RS, Dodson GE, Limbo O, Yamada Y, Williams JS, Guenther G, Classen S, et al. Nbs1 flexibly tethers Ctp1 and Mre11-Rad50 to coordinate DNA double-strand break processing and repair. Cell 2009, 139: 87–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lloyd J, Chapman JR, Clapperton JA, Haire LF, Hartsuiker E, Li J, Carr AM, et al. A supramodular FHA/BRCT-repeat architecture mediates Nbs1 adaptor function in response to DNA damage. Cell 2009, 139: 100–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Paull TT, Deshpande RA.. The Mre11/Rad50/Nbs1 complex: recent insights into catalytic activities and ATP-driven conformational changes. Exp Cell Res 2014, 329: 139–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang H, Shi LZ, Wong CCL, Han X, Hwang PYH, Truong LN, Zhu QY, et al. The interaction of CtIP and Nbs1 connects CDK and ATM to regulate HR-mediated double-strand break repair. PLoS Genet 2013, 9: e1003277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hopfner KP, Karcher A, Shin DS, Craig L, Arthur LM, Carney JP, Tainer JA.. Structural biology of Rad50 ATPase: ATP-driven conformational control in DNA double-strand break repair and the ABC-ATPase superfamily. Cell 2000, 101: 789–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Deshpande RA, Williams GJ, Limbo O, Williams RS, Kuhnlein J, Lee JH, Classen S, et al. ATP-driven Rad50 conformations regulate DNA tethering, end resection, and ATM checkpoint signaling. EMBO J 2014, 33: 482–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bhaskara V, Dupré A, Lengsfeld B, Hopkins BB, Chan A, Lee JH, Zhang XM, et al. Rad50 adenylate kinase activity regulates DNA tethering by Mre11/Rad50 complexes. Mol Cell 2007, 25: 647–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Raymond WE, Kleckner N.. RAD50 protein of S. cerevisiae exhibits ATP-dependent DNA binding. Nucleic Acids Res 1993, 21: 3851–3856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Buis J, Wu Y, Deng Y, Leddon J, Westfield G, Eckersdorff M, Sekiguchi JM, et al. Mre11 nuclease activity has essential roles in DNA repair and genomic stability distinct from ATM activation. Cell 2008, 135: 85–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shibata A, Moiani D, Arvai AS, Perry J, Harding SM, Genois MM, Maity R, et al. DNA double-strand break repair pathway choice is directed by distinct MRE11 nuclease activities. Mol Cell 2014, 53: 7–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jazayeri A, Balestrini A, Garner E, Haber JE, Costanzo V.. Mre11–Rad50–Nbs1-dependent processing of DNA breaks generates oligonucleotides that stimulate ATM activity. EMBO J 2008, 27: 1953–1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Paull TT, Gellert M.. The 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity of Mre11 facilitates repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Mol Cell 1998, 1: 969–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Williams RS, Moncalian G, Williams JS, Yamada Y, Limbo O, Shin DS, Groocock LM, et al. Mre11 dimers coordinate DNA end bridging and nuclease processing in double-strand-break repair. Cell 2008, 135: 97–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Garcia V, Phelps SEL, Gray S, Neale MJ.. Bidirectional resection of DNA double-strand breaks by Mre11 and Exo1. Nature 2011, 479: 241–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Neale MJ, Pan J, Keeney S.. Endonucleolytic processing of covalent protein-linked DNA double-strand breaks. Nature 2005, 436: 1053–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhu Z, Chung WH, Shim EY, Lee SE, Ira G.. Sgs1 helicase and two nucleases Dna2 and Exo1 resect DNA double-strand break ends. Cell 2008, 134: 981–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chen L, Nievera CJ, Lee AY-L, Wu X.. Cell cycle-dependent complex formation of BRCA1.CtIP.MRN is important for DNA double-strand break repair. J Biol Chem 2008, 283: 7713–7720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yuan J, Chen J.. N terminus of CtIP is critical for homologous recombination-mediated double-strand break repair. J Biol Chem 2009, 284: 31746–31752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.You Z, Bailis JM.. DNA damage and decisions: CtIP coordinates DNA repair and cell cycle checkpoints. Trends Cell Biol 2010, 20: 402–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lengsfeld BM, Rattray AJ, Bhaskara V, Ghirlando R, Paull TT.. Sae2 is an endonuclease that processes hairpin DNA cooperatively with the Mre11/Rad50/Xrs2 complex. Mol Cell 2007, 28: 638–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Makharashvili N, Tubbs AT, Yang SH, Wang H, Barton O, Zhou Y, Deshpande RA, et al. Catalytic and noncatalytic roles of the CtIP endonuclease in double-strand break end resection. Mol Cell 2014, 54: 1022–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang H, Li Y, Truong LN, Shi LZ, Hwang PYH, He J, Do J, et al. CtIP maintains stability at common fragile sites and inverted repeats by end resection-independent endonuclease activity. Mol Cell 2014, 54: 1012–1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hartsuiker E, Mizuno K, Molnar M, Kohli J, Ohta K, Carr AM.. Ctp1CtIP and Rad32Mre11 nuclease activity are required for Rec12Spo11 removal, but Rec12Spo11 removal is dispensable for other MRN-dependent meiotic functions. Mol Cell Biol 2009, 29: 1671–1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hartsuiker E, Neale MJ, Carr AM.. Distinct requirements for the Rad32Mre11 nuclease and Ctp1CtIP in the removal of covalently bound topoisomerase I and II from DNA. Mol Cell 2009, 33: 117–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Llorente B, Symington LS.. The Mre11 nuclease is not required for 5′ to 3′ resection at multiple HO-induced double-strand breaks. Mol Cell Biol 2004, 24: 9682–9694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Langerak P, Mejia-Ramirez E, Limbo O, Russell P.. Release of Ku and MRN from DNA ends by Mre11 nuclease activity and Ctp1 is required for homologous recombination repair of double-strand breaks. PLoS Genet 2011, 7: e1002271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shim EY, Chung WH, Nicolette ML, Zhang Y, Davis M, Zhu Z, Paull TT, et al. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mre11/Rad50/Xrs2 and Ku proteins regulate association of Exo1 and Dna2 with DNA breaks. EMBO J 2010, 29: 3370–3380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mimitou EP, Symington LS.. Ku prevents Exo1 and Sgs1-dependent resection of DNA ends in the absence of a functional MRX complex or Sae2. EMBO J 2010, 29: 3358–3369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nicolette ML, Lee K, Guo Z, Rani M, Chow JM, Lee SE, Paull TT.. Mre11–Rad50–Xrs2 and Sae2 promote 5′ strand resection of DNA double-strand breaks. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2010, 17: 1478–1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cejka P, Cannavo E, Polaczek P, Masuda-Sasa T, Pokharel S, Campbell JL, Kowalczykowski SC.. DNA end resection by Dna2–Sgs1–RPA and its stimulation by Top3–Rmi1 and Mre11–Rad50–Xrs2. Nature 2010, 467: 112–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Niu H, Chung WH, Zhu Z, Kwon Y, Zhao W, Chi P, Prakash R, et al. Mechanism of the ATP-dependent DNA end-resection machinery from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 2010, 467: 108–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nimonkar AV, Genschel J, Kinoshita E, Polaczek P, Campbell JL, Wyman C, Modrich P, et al. BLM–DNA2–RPA–MRN and EXO1–BLM–RPA–MRN constitute two DNA end resection machineries for human DNA break repair. Genes Dev 2011, 2: 350–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ma JL, Kim EM, Haber JE, Lee SE.. Yeast Mre11 and Rad1 proteins define a Ku-independent mechanism to repair double-strand breaks lacking overlapping end sequences. Mol Cell Biol 2003, 23: 8820–8828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.McVey M, Lee SE.. MMEJ repair of double-strand breaks (director’s cut): deleted sequences and alternative endings. Trends Genet 2008, 24: 529–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Truong LN, Li Y, Shi LZ, Hwang PYH, He J, Wang H, Razavian N, et al. Microhomology-mediated end joining and homologous recombination share the initial end resection step to repair DNA double-strand breaks in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013, 110: 7720–7725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ira G, Haber JE.. Characterization of RAD51-independent break-induced replication that acts preferentially with short homologous sequences. Mol Cell Biol 2002, 22: 6384–6392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Deng SK, Gibb B, de Almeida MJ, Greene EC, Symington LS.. RPA antagonizes microhomology-mediated repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2014, 21: 405–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gravel S, Chapman JR, Magill C, Jackson SP.. DNA helicases Sgs1 and BLM promote DNA double-strand break resection. Genes Dev 2008, 22: 2767–2772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mimitou EP, Symington LS.. DNA end resection: many nucleases make light work. DNA Repair (Amst) 2009, 8: 983–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tran PT, Erdeniz N, Symington LS, Liskay RM.. EXO1-A multi-tasking eukaryotic nuclease. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004, 3: 1549–1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lee BI, Wilson DM.. The RAD2 domain of human exonuclease 1 exhibits 5′ to 3′ exonuclease and flap structure-specific endonuclease activities. J Biol Chem 1999, 274: 37763–37769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Keijzers G, Bohr V, Juel Rasmussen L.. Human exonuclease 1 (EXO1) activity characterization and its function on FLAP structures. Biosci Rep 2015, 35: e00206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Liao S, Toczylowski T, Yan H.. Mechanistic analysis of Xenopus EXO1’s function in 5′-strand resection at DNA double-strand breaks. Nucleic Acids Res 2011, 39: 5967–5977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tomimatsu N, Mukherjee B, Deland K, Kurimasa A, Bolderson E, Khanna KK, Burma S.. Exo1 plays a major role in DNA end resection in humans and influences double-strand break repair and damage signaling decisions. DNA Repair (Amst) 2012, 11: 441–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tsubouchi H, Ogawa H.. Exo1 roles for repair of DNA double-strand breaks and meiotic crossing over in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell 2000, 11: 2221–2233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Schaetzlein S, Chahwan R, Avdievich E, Roa S, Wei K, Eoff RL, Sellers RS, et al. Mammalian Exo1 encodes both structural and catalytic functions that play distinct roles in essential biological processes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013, 110: E2470–E2479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bertuch AA, Lundblad V.. EXO1 contributes to telomere maintenance in both telomerase-proficient and telomerase-deficient Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 2004, 166: 1651–1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nimonkar AV, Ozsoy AZ, Genschel J, Modrich P, Kowalczykowski SC.. Human exonuclease 1 and BLM helicase interact to resect DNA and initiate DNA repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008, 105: 16906–16911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chen X, Paudyal SC, Chin RI, You Z.. PCNA promotes processive DNA end resection by Exo1. Nucleic Acids Res 2013, 41: 9325–9338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ngo GHP, Balakrishnan L, Dubarry M, Campbell JL, Lydall D.. The 9-1-1 checkpoint clamp stimulates DNA resection by Dna2-Sgs1 and Exo1. Nucleic Acids Res 2014, 42: 10516–10528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ngo GHP, Lydall D.. The 9-1-1 checkpoint clamp coordinates resection at DNA double strand breaks. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43: 5017–5032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Eid W, Steger M, El-Shemerly M, Ferretti LP, Peña-Diaz J, König C, Valtorta E, et al. DNA end resection by CtIP and exonuclease 1 prevents genomic instability. EMBO Rep 2010, 11: 962–968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kousholt AN, Fugger K, Hoffmann S, Larsen BD, Menzel T, Sartori AA, Sørensen CS.. CtIP-dependent DNA resection is required for DNA damage checkpoint maintenance but not initiation. J Cell Biol 2012, 197: 869–876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Bae SH, Kim DW, Kim J, Kim JH, Kim DH, Kim HD, Kang HY, et al. Coupling of DNA helicase and endonuclease activities of yeast Dna2 facilitates Okazaki fragment processing. J Biol Chem 2002, 277: 26632–26641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kumar S, Burgers PM.. Lagging strand maturation factor Dna2 is a component of the replication checkpoint initiation machinery. Genes Dev 2013, 27: 313–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Levikova M, Cejka P.. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Dna2 can function as a sole nuclease in the processing of Okazaki fragments in DNA replication. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43: 7888–7897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lin W, Sampathi S, Dai H, Liu C, Zhou M, Hu J, Huang Q, et al. Mammalian DNA2 helicase/nuclease cleaves G-quadruplex DNA and is required for telomere integrity. EMBO J 2013, 32: 1425–1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Masuda-Sasa T, Polaczek P, Peng XP, Chen L, Campbell JL.. Processing of G4 DNA by Dna2 helicase/nuclease and replication protein A (RPA) provides insights into the mechanism of Dna2/RPA substrate recognition. J Biol Chem 2008, 283: 24359–24373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Daley JM, Chiba T, Xue X, Niu H, Sung P.. Multifaceted role of the Topo IIIα-RMI1-RMI2 complex and DNA2 in the BLM-dependent pathway of DNA break end resection. Nucleic Acids Res 2014, 42: 11083–11091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Toczylowski T, Yan H.. Mechanistic analysis of a DNA end processing pathway mediated by the Xenopus Werner syndrome protein. J Biol Chem 2006, 281: 33198–33205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Liao S, Toczylowski T, Yan H.. Identification of the Xenopus DNA2 protein as a major nuclease for the 5′→3′ strand-specific processing of DNA ends. Nucleic Acids Res 2008, 36: 6091–6100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Yan H, Toczylowski T, McCane J, Chen C, Liao S.. Replication protein A promotes 5′→3′ end processing during homology-dependent DNA double-strand break repair. J Cell Biol 2011, 192: 251–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Tammaro M, Liao S, McCane J, Yan H.. The N-terminus of RPA large subunit and its spatial position are important for the 5′→3′ resection of DNA double-strand breaks. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43: 8790–8800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Sturzenegger A, Burdova K, Kanagaraj R, Levikova M, Pinto C, Cejka P, Janscak P.. DNA2 cooperates with the WRN and BLM RecQ helicases to mediate long-range DNA-end resection in human cells. J Biol Chem 2014, 289: 27314–27326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Zhou C, Pourmal S, Pavletich NP.. Dna2 nuclease-helicase structure, mechanism and regulation by Rpa. Elife 2015, 4: 1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Levikova M, Klaue D, Seidel R, Cejka P.. Nuclease activity of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Dna2 inhibits its potent DNA helicase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013, 110: E1992–E2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Krasner DS, Daley JM, Sung P, Niu H.. Interplay between Ku and replication protein A in the restriction of Exo1-mediated DNA break end resection. J Biol Chem 2015, 290: 18806–18816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Chen H, Lisby M, Symington L.. RPA coordinates DNA end resection and prevents formation of DNA hairpins. Mol Cell 2013, 50: 589–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Cannavo E, Cejka P, Kowalczykowski SC.. Relationship of DNA degradation by Saccharomyces cerevisiae exonuclease 1 and its stimulation by RPA and Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2 to DNA end resection. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2013, 110: E1661–E1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Toledo LI, Altmeyer M, Rask MB, Lukas C, Larsen DH, Povlsen LK, Bekker-Jensen S, et al. ATR prohibits replication catastrophe by preventing global exhaustion of RPA. Cell 2013, 155: 1088–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.El-shemerly M, Janscak P, Hess D, Jiricny J, Ferrari S.. Degradation of human exonuclease 1b upon DNA synthesis inhibition. Cancer Res 2005, 65: 3604–3609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Chen X, Kim I, Honaker Y, Paudyal SC, Koh WK, Sparks M, Li S, et al. 14-3-3 proteins restrain the Exo1 nuclease to prevent overresection. J Biol Chem 2015, 290: 12300–12312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Engels K, Giannattasio M, Muzi-falconi M, Lopes M, Ferrari S.. 14-3-3 Proteins regulate exonuclease 1 – dependent processing of stalled replication forks. PLoS Genet 2011, 7: e1001367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Andersen SD, Keijzers G, Rampakakis E, Engels K, Luhn P, El-Shemerly M, Nielsen FC, et al. 14-3-3 checkpoint regulatory proteins interact specifically with DNA repair protein human exonuclease 1 (hEXO1) via a semi-conserved motif. DNA Repair (Amst) 2012, 11: 267–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Tkáč J, Xu G, Adhikary H, Young JTF, Gallo D, Escribano-Díaz C, Krietsch J, et al. HELB is a feedback inhibitor of DNA end resection. Mol Cell 2016, 61: 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Nimonkar AV, Kowalczykowski SC.. Second-end DNA capture in double-strand break repair: how to catch a DNA by its tail. Cell Cycle 2009, 8: 1816–1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Nimonkar AV, Sica RA, Kowalczykowski SC.. Rad52 promotes second-end DNA capture in double-stranded break repair to form complement-stabilized joint molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009, 106: 3077–3082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.McIlwraith MJ, West SC.. DNA repair synthesis facilitates RAD52-mediated second-end capture during DSB repair. Mol Cell 2008, 29: 510–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Lao JP, Oh SD, Shinohara M, Shinohara A, Hunter N.. Rad52 promotes postinvasion steps of meiotic double-strand-break repair. Mol Cell 2008, 29: 517–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Karanja K, Lee EH, Hendrickson E, Campbell JL.. Preventing over-resection by DNA2 helicase/nuclease suppresses repair defects in Fanconi anemia cells. Cell Cycle 2014, 13: 1540–1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Zhang JM, Liu XM, Ding YH, Xiong LY, Ren JY, Zhou ZX, Wang HT, et al. Fission yeast Pxd1 promotes proper DNA repair by activating Rad16XPF and inhibiting Dna2. PLoS Biol 2014, 12: e1001946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Rossiello F, Herbig U, Longhese MP, Fumagalli M, d’Adda di Fagagna F.. Irreparable telomeric DNA damage and persistent DDR signalling as a shared causative mechanism of cellular senescence and ageing. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2014, 26: 89–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Roberts SA, Sterling J, Thompson C, Harris S, Mav D, Shah R, Klimczak LJ, et al. Clustered mutations in yeast and in human cancers can arise from damaged long single-strand DNA regions. Mol Cell 2012, 46: 424–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Stephens PJ, Greenman CD, Fu B, Yang F, Bignell GR, Mudie LJ, Pleasance ED, et al. Massive genomic rearrangement acquired in a single catastrophic event during cancer development. Cell 2011, 144: 27–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.VanHulle K, Lemoine FJ, Narayanan V, Downing B, Hull K, McCullough C, Bellinger M, et al. Inverted DNA repeats channel repair of distant double-strand breaks into chromatid fusions and chromosomal rearrangements. Mol Cell Biol 2007, 27: 2601–2614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Rothkamm K, Krüger I, Thompson LH, Kru I, Lo M.. Pathways of DNA double-strand break repair during the mammalian cell cycle pathways of DNA double-strand break repair during the mammalian cell cycle. Mol Cell Biol 2003, 23: 5706–5715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Barlow JH, Lisby M, Rothstein R.. Differential regulation of the cellular response to DNA double-strand breaks in G1. Mol Cell 2008, 30: 73–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Zierhut C, Diffley JFX.. Break dosage, cell cycle stage and DNA replication influence DNA double strand break response. EMBO J 2008, 27: 1875–1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Shao Z, Davis AJ, Fattah KR, So S, Sun J, Lee KJ, Harrison L, et al. Persistently bound Ku at DNA ends attenuates DNA end resection and homologous recombination. DNA Repair (Amst) 2012, 11: 310–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Sun J, Lee KJ, Davis AJ, Chen DJ.. Human Ku70/80 protein blocks exonuclease 1-mediated DNA resection in the presence of human Mre11 or Mre11/Rad50 protein complex. J Biol Chem 2012, 287: 4936–4945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Downs JA, Jackson SP.. A means to a DNA end: the many roles of Ku. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2004, 5: 367–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Yun MH, Hiom K.. CtIP-BRCA1 modulates the choice of DNA double-strand-break repair pathway throughout the cell cycle. Nature 2009, 459: 460–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Quennet V, Beucher A, Barton O, Takeda S, Löbrich M.. CtIP and MRN promote non-homologous end-joining of etoposide-induced DNA double-strand breaks in G1. Nucleic Acids Res 2011, 39: 2144–2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Wohlbold L, Merrick KA, De S, Amat R, Kim JH, Larochelle S, Allen JJ, et al. Chemical genetics reveals a specific requirement for Cdk2 activity in the DNA damage response and identifies Nbs1 as a Cdk2 substrate in human cells. PLoS Genet 2012, 8: e1002935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Falck J, Forment JV, Coates J, Mistrik M, Lukas J, Bartek J, Jackson SP.. CDK targeting of NBS1 promotes DNA-end resection, replication restart and homologous recombination. EMBO Rep 2012, 13: 561–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Buis J, Stoneham T, Spehalski E, Ferguson DO.. Mre11 regulates CtIP-dependent double-strand break repair by interaction with CDK2. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2012, 19: 246–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Huertas P, Cortés-Ledesma F, Sartori AA, Aguilera A, Jackson SP.. CDK targets Sae2 to control DNA-end resection and homologous recombination. Nature 2008, 455: 689–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Huertas P, Jackson SP.. Human CtIP mediates cell cycle control of DNA end resection and double strand break repair. J Biol Chem 2009, 284: 9558–9565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Yu X, Chen J.. DNA damage-induced cell cycle checkpoint control requires CtIP, a phosphorylation-dependent binding partner of BRCA1 C-terminal domains. Mol Cell Biol 2004, 24: 9478–9486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Chen X, Niu H, Chung WH, Zhu Z, Papusha A, Shim EY, Lee SE, et al. Cell cycle regulation of DNA double-strand break end resection by Cdk1-dependent Dna2 phosphorylation. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2011, 18: 1015–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Tomimatsu N, Mukherjee B, Hardebeck MC, Ilcheva M, Camacho CV, Harris JL, Porteus M, et al. Phosphorylation of EXO1 by CDKs 1 and 2 regulates DNA end resection and repair pathway choice. Nat Commun 2014, 5: 3561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Morrison C, Rieder CL.. Chromosome damage and progression into and through mitosis in vertebrates. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004, 3: 1133–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Giunta S, Belotserkovskaya R, Jackson SP.. DNA damage signaling in response to double-strand breaks during mitosis. J Cell Biol 2010, 190: 197–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Peterson SE, Li Y, Chait BT, Gottesman ME, Baer R, Gautier J.. Cdk1 uncouples CtIP-dependent resection and Rad51 filament formation during M-phase double-strand break repair. J Cell Biol 2011, 194: 705–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Matsuoka S, Ballif BA, Smogorzewska A, McDonald ER, Hurov KE, Luo J, Bakalarski CE, et al. ATM and ATR substrate analysis reveals extensive protein networks responsive to DNA damage. Science 2007, 316: 1160–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Stokes MP, Rush J, Macneill J, Ren JM, Sprott K, Nardone J, Yang V, et al. Profiling of UV-induced ATM/ATR signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007, 104: 19855–19860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Peterson SE, Li Y, Wu-Baer F, Chait BT, Baer R, Yan H, Gottesman ME, et al. Activation of DSB processing requires phosphorylation of CtIP by ATR. Mol Cell 2013, 49: 657–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Baroni E, Viscardi V, Cartagena-Lirola H, Lucchini G, Longhese MP.. The functions of budding yeast Sae2 in the DNA damage response require Mec1- and Tel1-dependent phosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol 2004, 24: 4151–4165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Cartagena-Lirola H, Guerini I, Viscardi V, Lucchini G, Longhese MP.. Budding yeast Sae2 is an in vivo target of the Mec1 and Tel1 checkpoint kinases during meiosis. Cell Cycle 2006, 5: 1549–1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Di Virgilio M, Ying CY, Gautier J.. PIKK-dependent phosphorylation of Mre11 induces MRN complex inactivation by disassembly from chromatin. DNA Repair (Amst) 2009, 8: 1311–1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Schlegel BP, Jodelka FM, Nunez R.. BRCA1 promotes induction of ssDNA by ionizing radiation. Cancer Res 2006, 66: 5181–5189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Cruz-García A, López-Saavedra A, Huertas P.. BRCA1 accelerates CtIP-mediated DNA-end resection. Cell Rep 2014, 9: 451–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Bunting SF, Callén E, Wong N, Chen HT, Polato F, Gunn A, Bothmer A, et al. 53BP1 inhibits homologous recombination in Brca1-deficient cells by blocking resection of DNA breaks. Cell 2010, 141: 243–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Aparicio T, Baer R, Gottesman M, Gautier J.. MRN, CtIP, and BRCA1 mediate repair of topoisomerase II–DNA adducts. J Cell Biol 2016, 212: 399–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, Tutt ANJ, Johnson DA, Richardson TB, Santarosa M, et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature 2005, 434: 917–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Bryant HE, Schultz N, Thomas HD, Parker KM, Flower D, Lopez E, Kyle S, et al. Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature 2005, 434: 913–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Bouwman P, Aly A, Escandell JM, Pieterse M, Bartkova J, van der Gulden H, Hiddingh S, et al. 53BP1 loss rescues BRCA1 deficiency and is associated with triple-negative and BRCA-mutated breast cancers. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2010, 17: 688–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Cao L, Xu X, Bunting SF, Liu J, Wang RH, Cao LL, Wu JJ, et al. A selective requirement for 53BP1 in the biological response to genomic instability induced by Brca1 deficiency. Mol Cell 2009, 35: 534–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Panier S, Boulton SJ.. Double-strand break repair: 53BP1 comes into focus. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2013, 15: 7–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Bothmer A, Robbiani DF, Feldhahn N, Gazumyan A, Nussenzweig A, Nussenzweig MC.. 53BP1 regulates DNA resection and the choice between classical and alternative end joining during class switch recombination. J Exp Med 2010, 207: 855–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Bothmer A, Robbiani DF, Di Virgilio M, Bunting SF, Klein IA, Feldhahn N, Barlow J, et al. Regulation of DNA end joining, resection, and immunoglobulin class switch recombination by 53BP1. Mol Cell 2011, 42: 319–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.Jaspers JE, Kersbergen A, Boon U, Sol W, Van Deemter L, Zander SA, Drost R, et al. Loss of 53BP1 causes PARP inhibitor resistance in BRCA1-mutated mouse mammary tumors. Cancer Discov 2013, 3: 68–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Callen E, Di Virgilio M, Kruhlak MJ, Nieto-Soler M, Wong N, Chen HT, Faryabi RB, et al. 53BP1 mediates productive and mutagenic DNA repair through distinct phosphoprotein interactions. Cell 2013, 153: 1266–1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Chapman JR, Barral P, Vannier JB, Borel V, Steger M, Tomas-Loba A, Sartori AA, et al. RIF1 is essential for 53BP1-dependent nonhomologous end joining and suppression of DNA double-strand break resection. Mol Cell 2013, 49: 858–871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180.Di Virgilio M, Callen E, Yamane A, Zhang W, Jankovic M, Gitlin AD, Feldhahn N, et al. Rif1 prevents resection of DNA breaks and promotes immunoglobulin class switching. Science 2013, 339: 711–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181.Zimmermann M, Lottersberger F, Buonomo SB.. 53BP1 regulates DSB repair using Rif1 to control 5′ end resection. Science 2013, 339: 700–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182.Feng L, Li N, Li Y, Wang J, Gao M, Wang W, Chen J.. Cell cycle-dependent inhibition of 53BP1 signaling by BRCA1. Cell Discov 2015, 1: 15019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 183.Feng L, Fong KW, Wang J, Wang W, Chen J.. RIF1 counteracts BRCA1-mediated end resection during DNA repair. J Biol Chem 2013, 288: 11135–11143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 184.Escribano-Díaz C, Orthwein A, Fradet-Turcotte A, Xing M, Young JTF, Tkáč J, Cook MA, et al. A cell cycle-dependent regulatory circuit composed of 53BP1-RIF1 and BRCA1-CtIP controls DNA repair pathway choice. Mol Cell 2013, 49: 872–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 185.Zhang H, Liu H, Chen Y, Yang X, Wang P, Liu T, Deng M, et al. A cell cycle-dependent BRCA1–UHRF1 cascade regulates DNA double-strand break repair pathway choice. Nat Commun 2016, 7: 10201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 186.Cheruiyot A, Paudyal SC, Kim I, Sparks M, Ellenberger T, Piwnica-worms H, You Z.. Poly(ADP-ribose)-binding promotes Exo1 damage recruitment and suppresses its nuclease activities. DNA Repair (Amst) 2015, 35: 106–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 187.Bologna S, Altmannova V, Valtorta E, Koenig C, Liberali P, Gentili C, Anrather D, et al. Sumoylation regulates EXO1 stability and processing of DNA damage. Cell Cycle 2015, 4101: 2439–2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 188.Steger M, Murina O, Hühn D, Ferretti LP, Walser R, Hänggi K, Lafranchi L, et al. Prolyl isomerase PIN1 regulates DNA double-strand break repair by counteracting DNA end resection. Mol Cell 2013, 50: 333–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 189.Broderick R, Nieminuszczy J, Baddock HT, Deshpande RA, Gileadi O, Paull TT, McHugh PJ, et al. EXD2 promotes homologous recombination by facilitating DNA end resection. Nat Cell Biol 2016, 18: 271–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 190.Liberti SE, Andersen SD, Wang J, May A, Miron S, Perderiset M, Keijzers G, et al. Bi-directional routing of DNA mismatch repair protein human exonuclease 1 to replication foci and DNA double strand breaks. DNA Repair (Amst) 2011, 10: 73–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 191.Zhang F, Shi J, Chen S-H, Bian C, Yu X.. The PIN domain of EXO1 recognizes poly(ADP-ribose) in DNA damage response. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43: 10782–10794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 192.Kaidi A, Weinert BT, Choudhary C, Stephen P.. Human SIRT6 promotes DNA-end resection through CtIP deacetylation. Science 2010, 329: 1348–1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 193.Daugaard M, Baude A, Fugger K, Povlsen LK, Beck H, Sørensen CS, Petersen NHT, et al. LEDGF (p75) promotes DNA-end resection and homologous recombination. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2012, 19: 803–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 194.Costelloe T, Louge R, Tomimatsu N, Mukherjee B, Martini E, Khadaroo B, Dubois K, et al. The yeast Fun30 and human SMARCAD1 chromatin remodellers promote DNA end resection. Nature 2012, 489: 581–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 195.Dong S, Han J, Chen H, Liu T, Huen MSYSY, Yang Y, Guo CX, et al. The human SRCAP chromatin remodeling complex promotes DNA-end resection. Curr Biol 2014, 24: 2097–2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 196.Yang SH, Zhou R, Campbell J, Chen J, Ha T, Paull TT.. The SOSS1 single-stranded DNA binding complex promotes DNA end resection in concert with Exo1. EMBO J 2013, 32: 126–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 197.Polo SE, Blackford AN, Chapman JR, Baskcomb L, Gravel S, Rusch A, Thomas A, et al. Regulation of DNA-end resection by hnRNPU-like proteins promotes DNA double-strand break signaling and repair. Mol Cell 2012, 45: 505–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 198.O’Sullivan RJ, Karlseder J.. Telomeres: protecting chromosomes against genome instability. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2010, 11: 171–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 199.Chai W, Du Q, Shay JW, Wright WE.. Human telomeres have different overhang sizes at leading versus lagging strands. Mol Cell 2006, 21: 427–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 200.Chow TT, Zhao Y, Mak SS, Shay JW, Wright WE.. Early and late steps in telomere overhang processing in normal human cells: the position of the final RNA primer drives telomere shortening. Genes Dev 2012, 26: 1167–1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]