Abstract

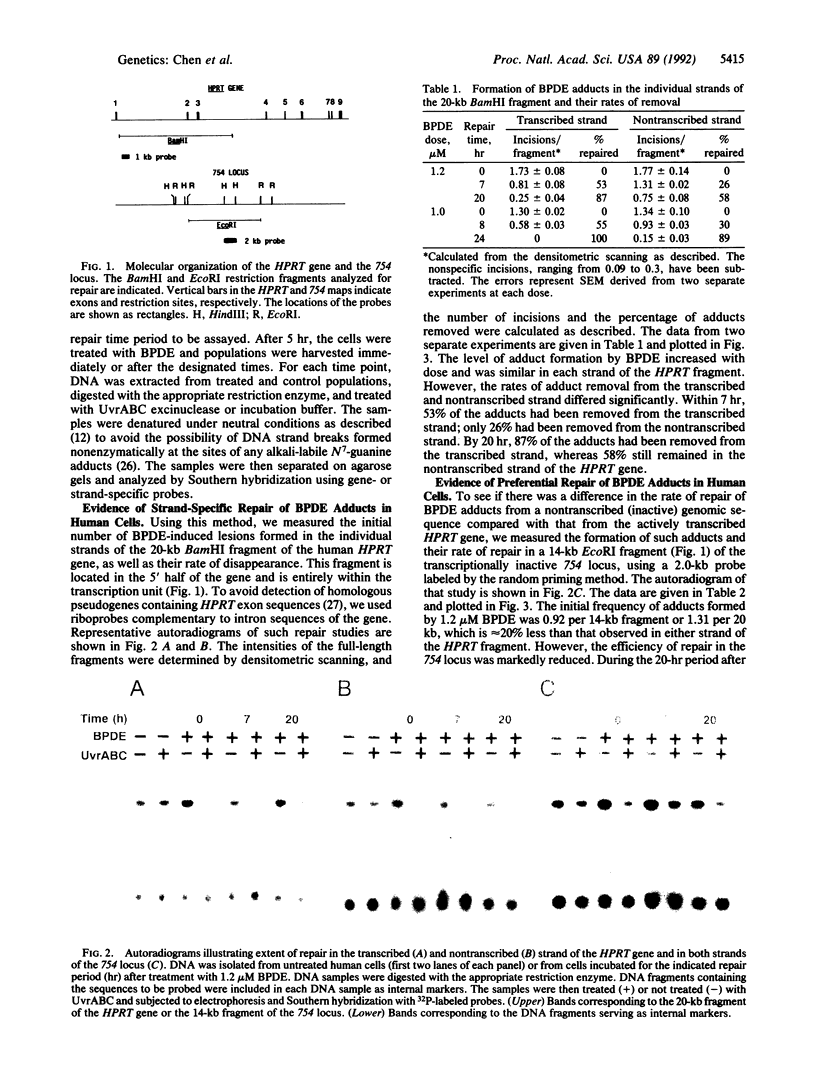

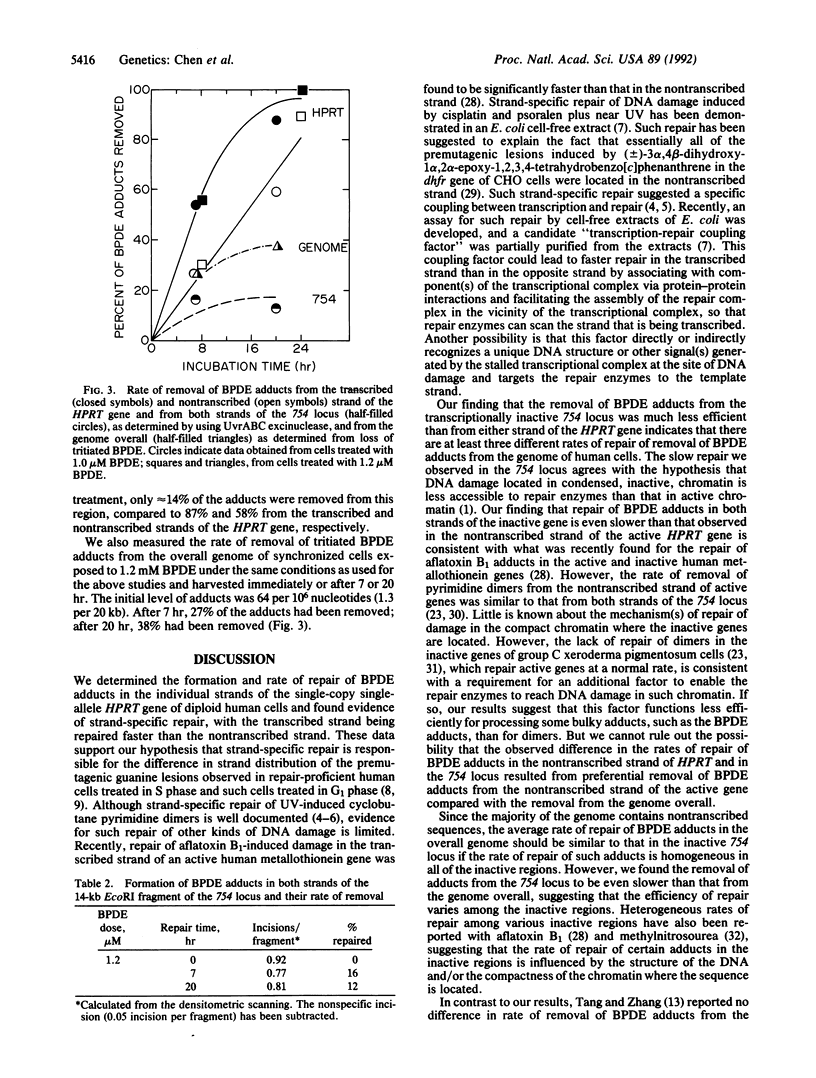

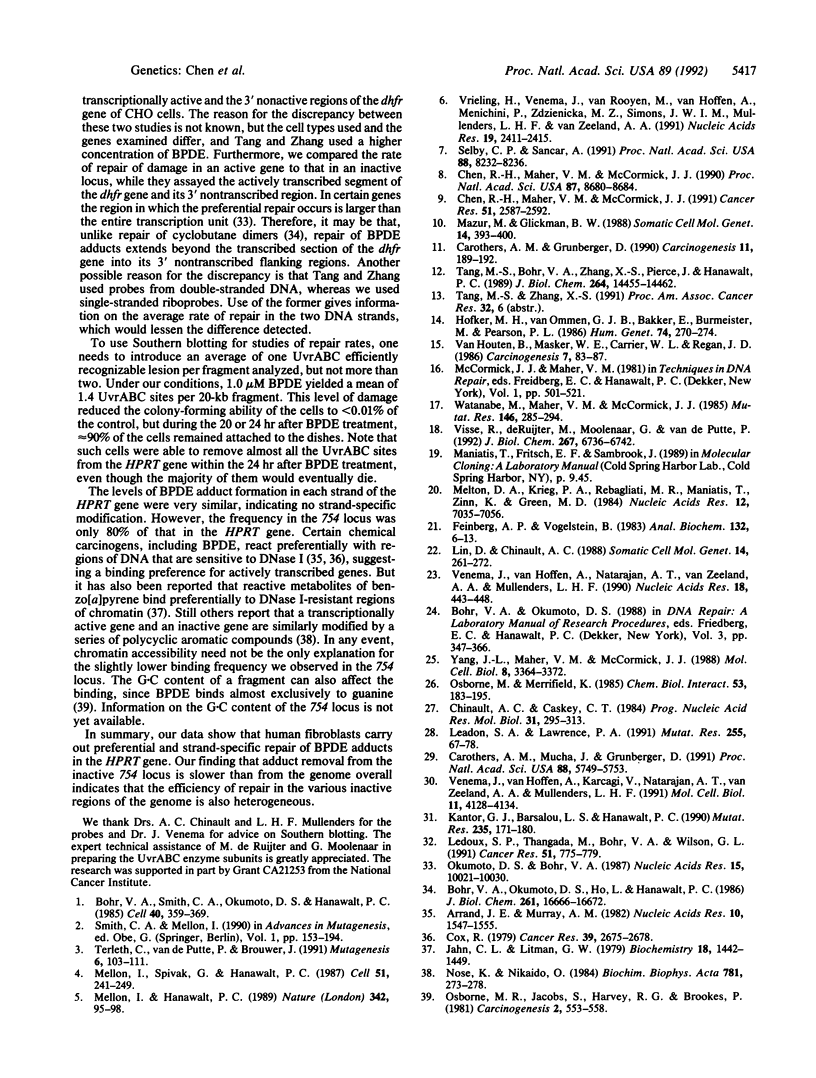

If excision repair-proficient human cells are allowed time for repair before onset of S phase, the premutagenic lesions formed by (+/-)-7 beta,8 alpha-dihydroxy-9 alpha,10 alpha-epoxy- 7,8,9,10-tetrahydrobenzo[a]pyrene (benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide, BPDE) are lost from the transcribed strand of the hypoxanthine (guanine) phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT) gene faster than from the nontranscribed strand. No change in strand distribution is seen with repair-deficient cells. These results suggest strand-specific repair of BPDE-induced DNA damage in human cells. To test this, we measured the initial number of BPDE adducts formed in each strand of the actively transcribed HPRT gene and the rate of repair, using UvrABC excinuclease in conjunction with Southern hybridization and strand-specific probes. We also measured the rate of loss of BPDE adducts from the inactive 754 locus. The frequencies of adducts formed by exposure to BPDE (1.0 or 1.2 microM) in either strand of a 20-kilobase fragment that lies entirely within the transcription unit of the HPRT gene were similar; the frequency in the 14-kilobase 754 fragment was approximately 20% lower. The rates of repair in the two strands of the HPRT fragment differed significantly. Within 7 hr after treatment with 1.2 microM BPDE, 53% of the adducts had been removed from the transcribed strand, but only 26% from the nontranscribed strand; after 20 hr, these values were 87% and 58%, respectively. In contrast, only approximately 14% of the BPDE adducts were lost from the 754 locus in 20 hr, a value even lower than the rate of loss from the overall genome (i.e., 38%). These results demonstrate strand-specific and preferential repair of BPDE adducts in human cells. They suggest that the heterogeneous repair of BPDE adducts in the human genome cannot be accounted for merely by the greatly increased rate of the repair specific to the transcribed strand of the active genes, and they point to a role for the chromatin structure.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Arrand J. E., Murray A. M. Benzpyrene groups bind preferentially to the DNA of active chromatin in human lung cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1982 Mar 11;10(5):1547–1555. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.5.1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohr V. A., Okumoto D. S., Ho L., Hanawalt P. C. Characterization of a DNA repair domain containing the dihydrofolate reductase gene in Chinese hamster ovary cells. J Biol Chem. 1986 Dec 15;261(35):16666–16672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohr V. A., Smith C. A., Okumoto D. S., Hanawalt P. C. DNA repair in an active gene: removal of pyrimidine dimers from the DHFR gene of CHO cells is much more efficient than in the genome overall. Cell. 1985 Feb;40(2):359–369. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90150-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carothers A. M., Grunberger D. DNA base changes in benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide-induced dihydrofolate reductase mutants of Chinese hamster ovary cells. Carcinogenesis. 1990 Jan;11(1):189–192. doi: 10.1093/carcin/11.1.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carothers A. M., Mucha J., Grunberger D. DNA strand-specific mutations induced by (+/-)-3 alpha,4 beta-dihydroxy- 1 alpha,2 alpha-epoxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydrobenzo[c]phenanthrene in the dihydrofolate reductase gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991 Jul 1;88(13):5749–5753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R. H., Maher V. M., McCormick J. J. Effect of excision repair by diploid human fibroblasts on the kinds and locations of mutations induced by (+/-)-7 beta,8 alpha-dihydroxy-9 alpha,10 alpha-epoxy-7,8,9,10- tetrahydrobenzo[a]pyrene in the coding region of the HPRT gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 Nov;87(21):8680–8684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R. H., Maher V. M., McCormick J. J. Lack of a cell cycle-dependent strand bias for mutations induced in the HPRT gene by (+/-)-7 beta,8 alpha-dihydroxy-9 alpha,10 alpha-epoxy-7,8,9,10-tetrahydrobenzo(a)pyrene in excision repair-deficient human cells. Cancer Res. 1991 May 15;51(10):2587–2592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinault A. C., Caskey C. T. The hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase gene: a model for the study of mutation in mammalian cells. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1984;31:295–313. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60381-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox R. Differences in the removal of N-methyl-N-nitrosourea-methylated products in DNase I-sensitive and -resistant regions of rat brain DNA. Cancer Res. 1979 Jul;39(7 Pt 1):2675–2678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg A. P., Vogelstein B. A technique for radiolabeling DNA restriction endonuclease fragments to high specific activity. Anal Biochem. 1983 Jul 1;132(1):6–13. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofker M. H., van Ommen G. J., Bakker E., Burmeister M., Pearson P. L. Development of additional RFLP probes near the locus for Duchenne muscular dystrophy by cosmid cloning of the DXS84 (754) locus. Hum Genet. 1986 Nov;74(3):270–274. doi: 10.1007/BF00282547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn C. L., Litman G. W. Accessibility of deoxyribonucleic acid in chromatin to the covalent binding of the chemical carcinogen benzo[a]pyrene. Biochemistry. 1979 Apr 17;18(8):1442–1449. doi: 10.1021/bi00575a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantor G. J., Barsalou L. S., Hanawalt P. C. Selective repair of specific chromatin domains in UV-irradiated cells from xeroderma pigmentosum complementation group C. Mutat Res. 1990 May;235(3):171–180. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(90)90071-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux S. P., Thangada M., Bohr V. A., Wilson G. L. Heterogeneous repair of methylnitrosourea-induced alkali-labile sites in different DNA sequences. Cancer Res. 1991 Feb 1;51(3):775–779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leadon S. A., Lawrence D. A. Preferential repair of DNA damage on the transcribed strand of the human metallothionein genes requires RNA polymerase II. Mutat Res. 1991 Jul;255(1):67–78. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(91)90019-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D., Chinault A. C. Comparative study of DNase I sensitivity at the X-linked human HPRT locus. Somat Cell Mol Genet. 1988 May;14(3):261–272. doi: 10.1007/BF01534587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur M., Glickman B. W. Sequence specificity of mutations induced by benzo[a]pyrene-7,8-diol-9,10-epoxide at endogenous aprt gene in CHO cells. Somat Cell Mol Genet. 1988 Jul;14(4):393–400. doi: 10.1007/BF01534647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellon I., Hanawalt P. C. Induction of the Escherichia coli lactose operon selectively increases repair of its transcribed DNA strand. Nature. 1989 Nov 2;342(6245):95–98. doi: 10.1038/342095a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellon I., Spivak G., Hanawalt P. C. Selective removal of transcription-blocking DNA damage from the transcribed strand of the mammalian DHFR gene. Cell. 1987 Oct 23;51(2):241–249. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90151-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melton D. A., Krieg P. A., Rebagliati M. R., Maniatis T., Zinn K., Green M. R. Efficient in vitro synthesis of biologically active RNA and RNA hybridization probes from plasmids containing a bacteriophage SP6 promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984 Sep 25;12(18):7035–7056. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.18.7035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nose K., Nikaido O. Transcriptionally active and inactive genes are similarly modified by chemical carcinogens or X-ray in normal human fibroblasts. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984 Apr 5;781(3):273–278. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(84)90093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okumoto D. S., Bohr V. A. DNA repair in the metallothionein gene increases with transcriptional activation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987 Dec 10;15(23):10021–10030. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.23.10021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne M. R., Jacobs S., Harvey R. G., Brookes P. Minor products from the reaction of (+) and (-) benzo[a]-pyrene-anti-diolepoxide with DNA. Carcinogenesis. 1981;2(6):553–558. doi: 10.1093/carcin/2.6.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne M., Merrifield K. Depurination of benzo[a]pyrene-diolepoxide treated DNA. Chem Biol Interact. 1985 Feb-Apr;53(1-2):183–195. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(85)80095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selby C. P., Sancar A. Gene- and strand-specific repair in vitro: partial purification of a transcription-repair coupling factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991 Sep 15;88(18):8232–8236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.18.8232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang M. S., Bohr V. A., Zhang X. S., Pierce J., Hanawalt P. C. Quantification of aminofluorene adduct formation and repair in defined DNA sequences in mammalian cells using the UVRABC nuclease. J Biol Chem. 1989 Aug 25;264(24):14455–14462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terleth C., van de Putte P., Brouwer J. New insights in DNA repair: preferential repair of transcriptionally active DNA. Mutagenesis. 1991 Mar;6(2):103–111. doi: 10.1093/mutage/6.2.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Houten B., Masker W. E., Carrier W. L., Regan J. D. Quantitation of carcinogen-induced DNA damage and repair in human cells with the UVR ABC excision nuclease from Escherichia coli. Carcinogenesis. 1986 Jan;7(1):83–87. doi: 10.1093/carcin/7.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venema J., van Hoffen A., Karcagi V., Natarajan A. T., van Zeeland A. A., Mullenders L. H. Xeroderma pigmentosum complementation group C cells remove pyrimidine dimers selectively from the transcribed strand of active genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1991 Aug;11(8):4128–4134. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.8.4128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venema J., van Hoffen A., Natarajan A. T., van Zeeland A. A., Mullenders L. H. The residual repair capacity of xeroderma pigmentosum complementation group C fibroblasts is highly specific for transcriptionally active DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990 Feb 11;18(3):443–448. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.3.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visse R., de Ruijter M., Moolenaar G. F., van de Putte P. Analysis of UvrABC endonuclease reaction intermediates on cisplatin-damaged DNA using mobility shift gel electrophoresis. J Biol Chem. 1992 Apr 5;267(10):6736–6742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrieling H., Venema J., van Rooyen M. L., van Hoffen A., Menichini P., Zdzienicka M. Z., Simons J. W., Mullenders L. H., van Zeeland A. A. Strand specificity for UV-induced DNA repair and mutations in the Chinese hamster HPRT gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991 May 11;19(9):2411–2415. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.9.2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M., Maher V. M., McCormick J. J. Excision repair of UV- or benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide-induced lesions in xeroderma pigmentosum variant cells is 'error free'. Mutat Res. 1985 Nov;146(3):285–294. doi: 10.1016/0167-8817(85)90070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J. L., Maher V. M., McCormick J. J. Kinds and spectrum of mutations induced by 1-nitrosopyrene adducts during plasmid replication in human cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1988 Aug;8(8):3364–3372. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.8.3364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]