Abstract

Objective

This study aims to find out the safety and efficiency of postoperative adjuvant transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) and radiotherapy (RT) in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients with portal vein tumor thrombus (PVTT).

Methods

From 2009 to 2010, a total of 92 HCC patients with PVTT were enrolled in this retrospective study. Patients were divided into three groups according to their adjuvant therapies (conservative group, n=51; TACE group, n=31; RT group, n=10).

Results

In our analysis, median survival in patients with postoperative adjuvant TACE (21.91±3.60 months) or RT (14.53±1.61 months) was significantly longer than patients with hepatectomy alone (8.99±1.03 months). But the difference between adjuvant TACE and RT was of no significance (P=0.716). Also a similar result could be observed in median disease-free survival: conservative group (6.51±1.44 months), TACE group (13.98±3.38 months), and RT group (14.03±2.40 months). Treatment strategies (hazard ratio [HR] =0.411, P<0.001) and PVTT type (HR =4.636, P<0.001) were the independent prognostic factors for overall survival. Similarly, the risk factors were the same when multivariate analysis was conducted in disease-free survival (treatment strategies, HR =0.423, P<0.001; PVTT type, HR =4.351, P<0.001) and recurrence (treatment strategies, HR =0.459, P=0.030; PVTT type, HR =2.908, P=0.047). Patients with PVTT type I had longer overall survival than patients with PVTT type II (median survival: 18.43±2.88 months vs 11.59±1.45 months, P=0.035).

Conclusion

Postoperative adjuvant TACE and RT may be a choice for HCC patients with PVTT.

Keywords: HCC, portal vein tumor thrombus, transarterial chemoembolization, radiotherapy, surgery

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common cancer in the world.1 Portal vein tumor thrombus (PVTT) was often found in 10%–40% patients when they were diagnosed with HCC.2–4 PVTT is the independent prognostic factor of unsatisfied overall survival (OS). Mean survival in untreated PVTT patients is only 2–4 months.

According to the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer group, HCC patients with PVTT are often defined as Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage C. Sorafenib used to be recommended to these patients.5–7 However, median survival in patients with sorafenib is only ~6.5 months.8 Nevertheless, many studies have figured out that surgery could significantly prolong OS in HCC patients with PVTT.9,10 The high incidence of postoperative HCC recurrence makes the OS rate unsatisfying.11 Various postoperative adjuvant therapies were used to decrease HCC recurrence rate and thus prolong the OS.12,13

Many studies have suggested that surgery combined with adjuvant transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) could increase the OS than surgery alone.14,15 The result of one meta-analysis showed that patients treated with surgery plus TACE not only obtained significantly longer disease-free survival (DFS) but also less mortality rate.16 Another adjuvant therapy is radiotherapy (RT). Preoperative RT has been reported to prolong OS in selected HCC patients with PVTT.17 Moreover, adjuvant RT could significantly prolong the DFS and OS in selected patients.18 Adjuvant TACE and RT have been proven efficient for HCC patients with PVTT, but which therapy would be better remains controversial. Moreover, most of the evidence regarding adjuvant therapy comes from retrospective studies, and the results should thus be regarded with caution.

Here, we explored the efficacy and safety of postoperative adjuvant TACE and RT in HCC patients with PVTT. Thus, we aimed to find out a better way to prolong OS in HCC patients with PVTT.

Patients and methods

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Guangxi Medical University and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and internationally accepted ethical guidelines. During their admission for surgery, the patients enrolled in this study signed a written consent for their information to be stored in the hospital databases and used for research. During data collection, the patient records were anonymized. Patient admission and consent procedures have been described before.19

Patients

This retrospective study involved 92 consecutive patients with PVTT admitted to the Affiliated Tumor Hospital of Guangxi Medical University for HCC hepatic resection. These patients were divided into three groups according to their adjuvant therapy from 2009 to 2010: RT group (n=10), TACE group (n=31), and conservative group (n=51).

To be included in our study, HCC patients: 1) had to be 18–75 years old; 2) have the presence of PVTT type I or II (PVTT not having reached the main trunk of the portal vein);20 3) have Child–Pugh stage A or B liver function; 4) been diagnosed with a resectable tumor;21 and 5) been diagnosed with HCC based on postoperative pathology.

Patients were excluded from the study if they: 1) had a history of preoperative therapy; 2) had other malignant tumors or extrahepatic metastases; 3) PVTT location expanded to the main trunk or more; and 4) patients with HCC recurrence within 1 month.

The classification of PVTT was performed according to the guidelines of the Shanghai Eastern Hepatobiliary Hospital, Second Military Medical University: type I, tumor thrombosis involving the second class or above portal vein branches; type II, tumor thrombosis involving the first class portal vein branches; type III, thrombosis involving the portal vein trunks; and type IV, thrombosis involving the superior mesenteric vein or inferior vena cava.20

Blood tests included routine blood examination, liver and kidney function tests, alpha fetoprotein, and electrolyte test. Moreover, imaging tests, including chest radiography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging, were also performed for these patients. Nevertheless, ultrasound test was also needed.

Surgical procedure

All patients underwent hepatectomy and embolectomy. During the surgery, detailed data on tumor size (maximal tumor diameter), degree of liver cirrhosis, blood loss, operating time, number of tumors, and PVTT location were recorded.

During the operation, PVTT was ultimately identified by intraoperative ultrasonography. Clamp crushing method was used for performing hepatectomy and Pringle maneuver was used to occlude the blood inflow of the liver distal to the PVTT. If the PVTT was located within the resection line, both HCC and PVTT were removed. If the PVTT was beyond the resection plane, the PVTT was extracted from the opened stump of the portal vein. After flushing with normal saline and confirming that no PVTT remained, the opened stump was closed with continuous sutures.

Adjuvant TACE procedure and management

Adjuvant TACE was performed only once in the first postoperative month. Seldinger technique was used to conduct the TACE procedure. After the injection of a mixture of 50–100 mg cisplatin or oxaliplatin, 30–50 mg doxorubicin, and 5–10 mL of lipiodol, embolization was performed. No patients underwent superselective TACE.

Adjuvant RT procedure and management

Adjuvant RT was performed in the first postoperative month. A 10 mV linear accelerator (Aowo International Technology Development, Shenzhen, People’s Republic of China) was used to perform three-dimensional conformal RT in patients who underwent RT. All the patients were trained to breathe in the supine treatment position with both arms raised above the head. A daily fraction of 2.0–3.0 Gy was delivered four times per week. RT was performed only for 1 month postoperatively. Total radiation dose was around 40 Gy (range 32–48 Gy). Both resection margin and portal vein were chosen for delivering RT.

The choice of adjuvant treatment

Each patient received computed tomography scanning in the first month after hepatectomy. Any patient detected with susceptible residual PVTT was included in the RT group, while other patients were included in the TACE group.

Follow-up

Patients were asked to come in for postoperative examination every month for the first 3 months, every 2 months for the following 6 months, and every 3 months for the next 6 months.

For follow-up examinations, the following tests were required: blood tests including routine blood examination, liver and kidney function tests, alpha fetoprotein and electrolyte test; and imaging tests including chest radiography, abdominal ultrasound, and computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging. Recurrence was defined as new HCC lesions being present on computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging with or without abnormal alpha fetoprotein levels.

Patients in the two adjuvant groups (TACE groups and RT group) only received adjuvant therapy once. After that, all patients (n=92) were given the same treatment. Once the recurrence of HCC was discovered, surgery, local ablation therapy, and/or regional or systematic therapy were performed depending on the status of the recurrent tumors, liver function, and general physical conditions. Patients with poor liver function or very advanced HCC were treated with palliative therapies.

Patients who could not be found or connected were defined as reaching the endpoint. The endpoint of OS was patients’ death and the endpoint of DFS was HCC recurrence and death. If recurrence of HCC was not detected in patients before their final follow-up, DFS was considered equal to OS.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes in our study were OS and DFS. We compared these two outcomes within three groups in order to find out which therapy is most efficient and safe. The secondary outcomes were adverse events (ADEs). Moreover, subgroup analysis depending on PVTT type was also performed. We aimed to find out the most efficient therapy in selected patients.

Statistical analysis

All data analyses were performed using SPSS 19.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). The threshold of statistical significance was defined as P<0.05. Normally distributed data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, while asymmetrically distributed data were expressed as median (range). The Kaplan–Meier method was used to calculate survival time (OS and DFS). Factors significantly associated with OS or DFS were identified by univariate logistic regression first. Then all significant univariate factors were examined by multivariate analysis using a stepwise logistic model.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

From 2009 to 2010, 95 potential eligible HCC patients with PVTT were included in this retrospective study. However, three of them were found to have recurrence of HCC within 1 month, thus these three patients were excluded. Finally, 92 patients with PVTT were enrolled (conservative group, n=51; TACE group, n=31; RT group, n=10). The basic characteristics in all the three groups were similar (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of hepatocellular carcinoma patients with portal vein tumor thrombus

| Item | No therapy group (n=51) | TACE group (n=31) | Radiotherapy group (n=10) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age ± SD | 49±11 | 48±15 | 47±16 | 0.794 |

| Sex (M), n (%) | 45 (88%) | 29 (94%) | 9 (90%) | 0.734 |

| Positive for HBeAg, n (%) | 11 (22%) | 6 (19%) | 3 (30%) | 0.777 |

| PLT, 109/L | 245±103 | 259±119 | 301±121 | 0.784 |

| Tbil, μmol/L | 19 (12–28) | 19 (13–30) | 18 (12–33) | 0.975 |

| ALB, g/L | 37±4 | 37±5 | 34±2 | 0.952 |

| ALT, U/L | 49 (27–89) | 46 (28–83) | 42 (20–78) | 0.127 |

| AST, U/L | 47 (25–85) | 44 (20–79) | 45 (25–81) | 0.904 |

| PT, seconds | 14±2 | 13±1 | 13±1 | 0.967 |

| AFP, mg/L | 893 (199–1,210) | 870 (510–1,210) | 972 (674–1,210) | 0.761 |

| Child–Pugh A/B | 47/4 | 30/1 | 10/0 | 0.486 |

| Ascites | 2 (4%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0.816 |

| Tumor size, cm | 12±7 | 10±4 | 11±6 | 0.961 |

| Tumor number (≥3), n (%) | 9 (18%) | 6 (19%) | 3 (30%) | 0.666 |

| Cirrhosis, n (%) | 47 (92%) | 28 (90%) | 9 (90%) | 0.948 |

| Blood loss, mL | 400 (180–650) | 350 (150–600) | 400 (200–650) | 0.713 |

| Operating time, minutes | 240 (180–400) | 280 (200–420) | 260 (180–420) | 0.871 |

| PVTT type, I/II | 30/21 | 17/14 | 6/4 | 0.927 |

Note: Normally distributed data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and asymmetrically distributed data are expressed as median (range).

Abbreviations: AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; ALB, albumin; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; PLT, platelet count; PT, prothrombin time; PVTT, portal vein tumor thrombus; SD, standard deviation; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; Tbil, total bilirubin.

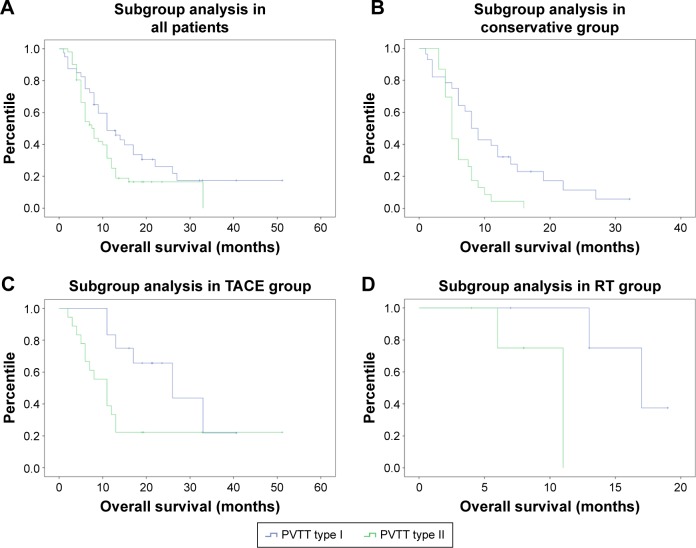

OS

Median survival time was 8.99±1.03, 21.91±3.60, and 14.53±1.61 months for the conservative, TACE, and RT groups, respectively. Both adjuvant groups (TACE vs conservative, P<0.001; RT vs conservative, P=0.017) showed significantly longer OS than the conservative group. However, the difference between the TACE and RT groups was not significant (P=0.716). The 6-, 12-, and 24-month OS rate was 49.0%, 19.6%, and 6.1% for patients in the conservative group, and 80.0%, 53.3%, and 31.8% for patients in the TACE group. For patients in the RT group, the 6- and 12-month survival was 88.9% and 71.1%, respectively. Data are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier curve of overall survival in three groups.

Abbreviations: RT, radiotherapy; TACE, transarterial embolization.

We conducted a multivariate analysis and found that treatment strategies (hazard ratio [HR] =0.411, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.266–0.635, P<0.001) and PVTT type (HR =4.636, 95% CI: 2.749–7.816, P<0.001) were independent prognostic factors for OS.

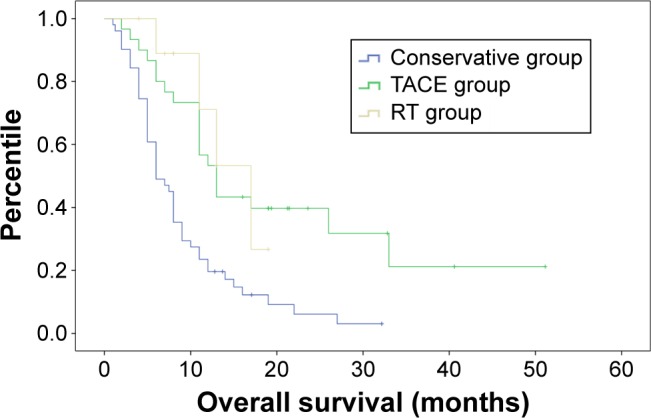

Disease-free survival

Median DFS was 6.51±1.44, 13.98±3.38, and 14.03±2.40 months for the conservative, TACE, and RT groups, respectively. Both adjuvant groups (TACE vs conservative, P=0.014; RT vs conservative, P=0.004) showed significantly longer DFS than the conservative group. However, the difference between the TACE and RT groups was not significant (P=0.078). The 6- and 12-month DFS rates were, respectively, 19.2%, and 9.9% for patients in the conservative group and 45.3% and 28.8% for patients in the TACE group. For patients in the RT group, the 6-month DFS rate was 66.7%. Data are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curve of disease-free survival in three groups.

Abbreviations: RT, radiotherapy; TACE, transarterial embolization.

We conducted multivariate analysis and found that treatment strategies (HR =0.423, 95% CI: 0.276–0.648, P<0.001) and PVTT type (HR =4.351, 95% CI: 2.328–8.134, P<0.001) were independent prognostic factors for DFS. According to the recurrence status, we conducted multivariate analysis and found that treatment strategies (HR =0.459, 95% CI: 0.227–0.928, P=0.030) and PVTT type (HR =2.908, 95% CI: 1.016–8.323, P=0.04:7) were associated with HCC recurrence.

In patients with recurrence, almost all patients were detected with intrahepatic recurrence of HCC, except 12 patients who were detected with extrahepatic recurrence of HCC (conservative group: five patients had occurrence of lung metastasis, two patients had occurrence of bone metastasis; TACE group: lung metastasis was seen in four patients; RT group: bone metastasis was seen in one patient).

Adverse events

No treatment-related deaths or serious ADEs was observed in our study. We found that patients in the TACE group had a higher risk of occurrence of nausea or vomiting (P=0.003). Other ADEs were similar among the three groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Complications and adverse events in different therapy groups

| Complications | Conservative therapy (n=51) | TACE group (n=31) | Radiotherapy (n=10) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nausea, vomiting, n (%) | 12 (24) | 18 (58) | 2 (20) | 0.003* |

| Fever, n (%) | 8 (16) | 11 (35) | 2 (20) | 0.130 |

| Pain, n (%) | 30 (60) | 22 (71) | 6 (60) | 0.547 |

| Alopecia, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.446 |

| Liver function impairment, n (%) | 6 (12) | 4 (13) | 2 (20) | 0.736 |

| Bleeding of esophageal venous plexus, n (%) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | >0.999 |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.446 |

| Infection, n (%) | 4 (8) | 3 (10) | 1 (10) | >0.999 |

| Refractory ascites, n (%) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | >0.999 |

| Pulmonary complication, n (%) | 2 (4) | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | 0.769 |

| Bone marrow suppression, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 1 (10) | 0.085 |

| Clavien–Dindo complications, grade I/II/III/IV, n | 40/8/3 | 23/6/2 | 7/2/1 | 0.906 |

Notes:

P<0.05. Subgroup analysis depending on PVTT type.

Abbreviations: PVTT, portal vein tumor thrombus; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization.

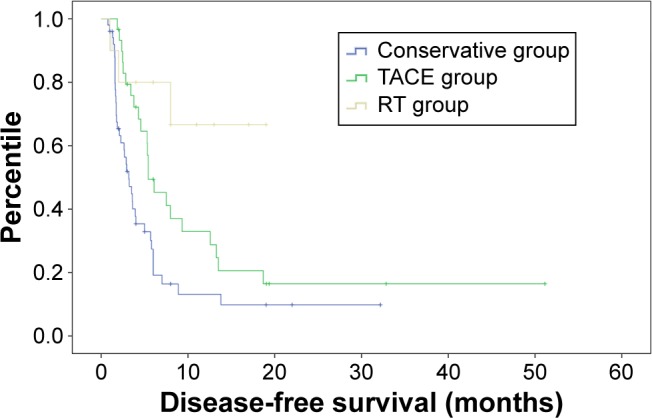

Subgroup analysis depending on PVTT type was performed, and we found that patients with PVTT type I (n=53) had significantly longer OS than patients with PVTT type II (n=39) (18.43±2.88 months vs 11.59±1.45 months, P=0.035). This subgroup analysis was also conducted in the conservative group (PVTT type I: n=30, 11.34±1.70 months; PVTT type II: n=21, 6.20±0.64 months, P=0.003), TACE group (PVTT type I: n=17, 26.30±3.62 months; PVTT type II: n=14, 17.58±4.29 months, P=0.025), and RT group (PVTT type I: n=6, 16.75±1.21 months; PVTT type II: n=4, 9.75±1.53 months, P=0.034). The results showed that patients with PVTT type I had significantly longer OS than patients with PVTT type II. Data are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier curve of subgroup analysis depending on PVTT type in three groups.

Notes: Subgroup analysis in (A) all patients, (B) conservative group, (C) TACE group, and (D) RT group.

Abbreviations: PVTT, portal vein tumor thrombus; RT, radiotherapy; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization.

Discussion

Patients with PVTT have been shown to have a poor survival rate.5 Surgery has been proven to significantly prolong survival in HCC patients with PVTT.22 Moreover, postoperative adjuvant therapies would also prolong OS than surgery alone.9,13 Adjuvant TACE has been proven to be safe and efficacious23 and adjuvant RT could significantly prolong the DFS and OS in selected patients.18 But the comparison between these two adjuvant therapies is rare to find and most of the evidence comes from retrospective studies, which should be regarded with caution. We aimed to find out the difference between adjuvant TACE and adjuvant RT in this study. Our results suggested that both adjuvant therapies could significantly prolong OS and DFS.

TACE procedure used to be contraindicated in patients with PVTT. This was attributed to hepatic necrosis induced by the interruption in the hepatic arterial blood supply.24,25 After hepatectomy and embolectomy, TACE may be a safe and efficient procedure. Peng et al23 studied patients undergoing surgical resection alone and TACE after surgical resection. They found that the median OS was better in patients with TACE after surgical resection (13 months) than resection alone (9 months). Fan et al14 also found that patients with surgical resection plus postoperative chemotherapy (15.1 months) had significantly longer mean OS than patients with surgery alone (10.1 months). Another study also conducted by Fan et al15 showed similar results. The purpose of postoperative adjuvant TACE was to eliminate the shed tumor cells by surgical manipulation of the liver or PVTT. Moreover, it also helps to destroy small intrahepatic metastases that may not have been detected preoperatively.26,27 Considering the earlier factors, postoperative adjuvant TACE could be effective and safe.

The use of RT in the treatment of HCC with PVTT is still controversial. The main reason is that the tolerance dose of the whole liver is much lower compared to the tumoricidal dose.28,29 The liver function adverse effect of radiation often conceals its positive antitumor effect. The advancement of technology has provided us with the means of delivering tumoricidal radiation doses to the partial liver. In comparison with whole liver irradiation, radiation adverse effect would be limited when patients receive partial liver radiation.30 Patients with PVTT have been shown to have a poor survival rate; this may be primarily attributed to the great risk of intra- or extrahepatic metastasis induced by PVTT.31,32 Postoperative adjuvant RT aims to irradiate microlesions caused by tumor thrombus or HCC itself.

In our analysis, survival in patients with postoperative adjuvant TACE (21.91 months) or RT (14.53 months) was significantly longer than patients with hepatectomy alone (8.99 months). But the difference between adjuvant TACE and RT was of no significance (P=0.716). Similar results could be observed in DFS. Multivariate analysis was used to analyze the prognostic factors associated with OS, and we found that treatment strategies (HR =0.411, P<0.001) and PVTT type (HR =4.636, P<0.001) were the independent prognostic factors for OS. Similarly, the risk factors were the same when multivariate analysis was conducted in DFS (treatment strategies, HR =0.423, P<0.001; PVTT type, HR =4.351, P<0.001) or HCC recurrence (treatment strategies, HR =0.459, P=0.030; PVTT type, HR =2.908, P=0.047). In the earlier analysis, PVTT was the independent risk factor for survival outcomes. Then we conducted subgroup analysis according to PVTT type. In our study, patients with PVTT extended to the main trunk of the portal vein were excluded. According to the PVTT classification by Shi et al,20 patients with PVTT type I had significantly longer survival (18.43 months) than patients with PVTT type II (11.59 months). Moreover, subgroup analysis was conducted in each treatment group, and we found similar results. The results of the study by Shi et al were similar to our previous study9 and other studies.20

Since the survival benefit between the two adjuvant therapies was similar, we focused on safety. TACE has been proven to increase the incidence of lung metastasis.33 Nevertheless, postoperative TACE could also increase the incidence of ADEs, including liver failure, bacteremia, and so on.34 RT would increase the incidence of gastric perforation, gastric bleeding, serious bone marrow suppression, and so on, which is especially remarkable in postoperative RT.35,36 In our study, no serious ADEs and no treatment-related deaths were observed. We found that patients in the adjuvant TACE group had higher incidence of nausea or vomiting. No significance was found in other ADEs, including liver function impairment, infection, or pulmonary complication. Clavien–Dindo complication scoring system was also used to evaluate the ADEs in three groups and no significance was found. All these evidences showed that both adjuvant TACE and RT were safe.

Limitations

The conclusions from our study should be interpreted with caution in light of several limitations. The biggest limitation was the study design. In our retrospective study, the treatment selection could not be decided, which may have led to selection bias. However, the patients baseline and medical records were similar among the three groups, which may reduce the selection bias. Second limitation was the sample size. Our sample size was small, especially in the RT group (n=10). This limitation may also lead to another bias. We searched many trials and analyzed their survival data and found that our results were similar. Thus, further studies with a large sample size and randomized design are needed to confirm our results.

Conclusion

In conclusion, postoperative adjuvant TACE and RT may be a good choice for HCC patients with PVTT.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Major Projects of National Science and Technology (no 2012ZX10002010001009), Key Laboratory of Early Prevention and Treatment for Regional High Frequency Tumor, Ministry of Education (GKE2015-ZZ06), and Self-Funded Research Project of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region National Health and Family Planning Commission (no Z2015710).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheung TK, Lai CL, Wong BC, Fung J, Yuen MF. Clinical features, biochemical parameters, and virological profiles of patients with hepa-tocellular carcinoma in Hong Kong. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24(4):573–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Minagawa M, Makuuchi M. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma accompanied by portal vein tumor thrombus. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(47):7561–7567. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i47.7561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park KW, Park JW, Choi JI, et al. Survival analysis of 904 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in a hepatitis B virus-endemic area. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23(3):467–473. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruix J, Gores GJ, Mazzaferro V. Hepatocellular carcinoma: clinical frontiers and perspectives. Gut. 2014;63(5):844–855. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Lope CR, Tremosini S, Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J. Management of HCC. J Hepatol. 2012;56(Suppl 1):S75–S87. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(12)60009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forner A, Llovet JM, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2012;379(9822):1245–1255. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61347-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(1):25–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ye JZ, Zhang YQ, Ye HH, et al. Appropriate treatment strategies improve survival of hepatocellular carcinoma patients with portal vein tumor thrombus. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(45):17141–17147. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i45.17141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang JH, Guo Z, Lu HF, et al. Adjuvant transarterial chemoembolization after curative resection of hepatocellular carcinoma: propensity score analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(15):4627–4634. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i15.4627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liccioni A, Reig M, Bruix J. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Digest Dis. 2014;32(5):554–563. doi: 10.1159/000360501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu SJ, Kim YJ. Effective treatment strategies other than sorafenib for the patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma invading portal vein. World J Hepatol. 2015;7(11):1553–1561. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i11.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhong JH, Li H, Li LQ, et al. Adjuvant therapy options following curative treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review of randomized trials. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2012;38(4):286–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fan J, Zhou J, Wu ZQ, et al. Efficacy of different treatment strategies for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(8):1215–1219. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i8.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fan J, Wu ZQ, Tang ZY, et al. Multimodality treatment in hepatocellular carcinoma patients with tumor thrombi in portal vein. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7(1):28–32. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i1.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhong JH, Li LQ. Postoperative adjuvant transarterial chemoembolization for participants with hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Hepatol Res. 2010;40(10):943–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2010.00710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamiyama T, Nakanishi K, Yokoo H, et al. Efficacy of preoperative radiotherapy to portal vein tumor thrombus in the main trunk or first branch in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Clin Oncol. 2007;12(5):363–368. doi: 10.1007/s10147-007-0701-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu W, Wang W, Rong W, et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy in centrally located hepatocellular carcinomas after hepatectomy with narrow margin (<1 cm): a prospective randomized study. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218(3):381–392. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhong JH, Li H, Xiao N, et al. Hepatic resection is safe and effective for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and portal hypertension. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e108755. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi J, Lai EC, Li N, et al. A new classification for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombus. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2011;18(1):74–80. doi: 10.1007/s00534-010-0314-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhong JH, Ke Y, Gong WF, et al. Hepatic resection associated with good survival for selected patients with intermediate and advanced-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2014;260(2):329–340. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zeng ZC, Fan J, Tang ZY, et al. A comparison of treatment combinations with and without radiotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein and/or inferior vena cava tumor thrombus. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61(2):432–443. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peng BG, He Q, Li JP, Zhou F. Adjuvant transcatheter arterial chemoembolization improves efficacy of hepatectomy for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and portal vein tumor thrombus. Am J Surg. 2009;198(3):313–318. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lau WY, Sangro B, Chen PJ, et al. Treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombosis: the emerging role for radioembolization using yttrium-90. Oncology. 2013;84(5):311–318. doi: 10.1159/000348325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jelic S, Sotiropoulos GC, ESMO Guidelines Working Group Hepatocellular carcinoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(Suppl 5):v59–v64. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ren ZG, Lin ZY, Xia JL, et al. Postoperative adjuvant arterial chemoembolization improves survival of hepatocellular carcinoma patients with risk factors for residual tumor: a retrospective control study. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10(19):2791–2794. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i19.2791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun HC, Tang ZY. Preventive treatments for recurrence after curative resection of hepatocellular carcinoma – a literature review of randomized control trials. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9(4):635–640. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i4.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lawrence TS, Robertson JM, Anscher MS, Jirtle RL, Ensminger WD, Fajardo LF. Hepatic toxicity resulting from cancer treatment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31(5):1237–1248. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)00418-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Emami B, Lyman J, Brown A, et al. Tolerance of normal tissue to therapeutic irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;21(1):109–122. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(91)90171-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim JY, Chung SM, Choi BO, Kay CS. Hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombosis: improved treatment outcomes with external beam radiation therapy. Hepatol Res. 2011;41(9):813–824. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2011.00826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamamoto J, Kosuge T, Takayama T, et al. Recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after surgery. Br J Surg. 1996;83(9):1219–1222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shirabe K, Kanematsu T, Matsumata T, Adachi E, Akazawa K, Sugimachi K. Factors linked to early recurrence of small hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy: univariate and multivariate analyses. Hepatology. 1991;14(5):802–805. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840140510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu H, Zhao W, Liu S, Zheng J, Ji G, Xie Y. Pure transcatheter arterial chemoembolization therapy for intrahepatic tumors causes a shrink in pulmonary metastases of hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(1):1035–1042. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheng X, Sun P, Hu QG, Song ZF, Xiong J, Zheng QC. Transarterial (chemo)embolization for curative resection of hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analyses. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2014;140(7):1159–1170. doi: 10.1007/s00432-014-1677-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hong TS, DeLaney TF, Mamon HJ, et al. A prospective feasibility study of respiratory-gated proton beam therapy for liver tumors. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2014;4(5):316–322. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang W, Zeng ZC, Zhang JY, Fan J, Zeng MS, Zhou J. Palliative radiation therapy for pulmonary metastases from hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2012;29(3):197–205. doi: 10.1007/s10585-011-9442-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]