Abstract

Introduction

Competence of nurses is a complex combination of knowledge, function, skills, attitudes, and values. Delivering care for patients in the Intensive Cardiac Care Unit (ICCU) requires nurses’ competences. This study aimed to explain nurses’ competence in the ICCU.

Methods

This was a qualitative study in which purposive sampling with maximum variation was used. Data were collected through semi-structured interviews with 23 participants during 2012–2013. Interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed by using the content-analysis method.

Results

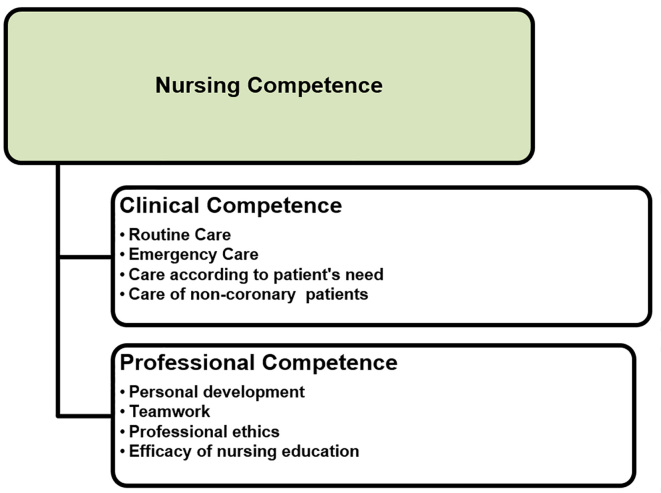

The main categories were “clinical competence,” comprising subcategories of ‘routine care,’ ‘emergency care,’ ‘care according to patients’ needs,’ ‘care of non-coronary patients’, as well as “professional competence,” comprising ‘personal development,’ ‘teamwork,’ ‘professional ethics,’ and ‘efficacy of nursing education.’

Conclusion

The finding of this study revealed dimensions of nursing competence in ICCU. Benefiting from competence leads to improved quality of patient care and satisfaction of patients and nurses and helps elevate nursing profession, improve nursing education, and clinical nursing.

Keywords: competence, nurses, intensive cardiac care unit, content analysis, professional ethics

1. Introduction

Competence is defined as knowledge and performance combined with psychomotor and clinical problem-solving skills and a responsive attitude (1). The concept of competence has been examined by several authors (2–7). Meretoja et al. defined nursing competence in terms of three dimensions, i.e., 1) the nurse’s ability to function professionally, 2) the knowledge and skills for collaborating within real-world practices with a degree of understanding, affection, and psychomotor skills, and 3) professional development and the willingness to acquire more skills (2–5). Bench et al. (2003) posited that the framework of coronary care competence is comprised of the nurse’s understanding of comprehensive patient assessment and the readjustment of her or his skills to provide satisfactory patient care, the management of medical and diet interventions, the ability to properly assess and respond to rapidly-changing conditions, the personal development and management of care programs for achieving desirable patient outcomes, and taking into account discharge schedules (8). Meretoja et al. (2004) considered competence to include general competence, professional competence, and clinical competence and experience (4). General competence involves an adequacy of performance and the ability to combine knowledge and skills around attitudes, values, and practices (4). Ability is translated to the rapid and correct assessment of patients’ conditions (9), while competence is an integral part of a wide-ranging knowledge (10). In their review of nurses’ competence, Loftin et al. (2013) wrote, “A clear and concise definition of competence has not yet been provided” (11). Nurses’ competence in CCU should be studied thoroughly to determine the many factors involved in its evaluation (12). CCU nursing, therefore, requires high standards of quality and competence (7), and assessing the competence of nurses in these units is vitally important, since patients’ lives are at stake and increasing opportunities for career development and professional growth are associated with improved quality of nursing care (3). Aari et al. (2008) also believed in the vitality of a systematic study of competence in intensive care units (7). Understanding the effects of the underlying factors and controlling these factors also are crucial to the development of competence (7). Qualitative research is a great tool for clarifying unexplored areas and provides an excellent opportunity for producing in-depth nursing knowledge through people’s experiences (13). Given the advantages of a qualitative study for exploring the theme of competence in intensive care units (7) and given that the qualitative content analysis method is used for the subjective interpretation of textual data through the regular classification of themes or explicit and implicit patterns in the text (14), the present study was conducted to examine the competence of nurses in the ICCU to overcome the lack of research in this particular area.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Setting

The present qualitative study explored the experiences of people; the meaning of phenomena in people’s perception can only be found by entering their world of experiences (15). Thus, the present study was conducted to examine the competence of nurses in the ICCU through the qualitative method of conventional content analysis for obtaining and analyzing rich data from participants. Content analysis is a systematic classification of data through which codes and themes emerge (16), and it is an important research technique in the social sciences that identifies and analyzes data. Thus, it also is useful for an in-depth investigation of the data related to nursing research and education (17). The study was performed in the ICCU of Kowsar (Fatemieh) Hospital in Semnan in 2012–2013. Maximum variation sampling was used to select the study’s subjects. Inclusion criteria for the participating nurses consisted of residing in Semnan, having at least a bachelor’s degree in nursing, having at least one year of full-time work experience in the ICCU, and a willingness to participate in the study and share their experiences. There were 23 subjects from Semnan who participated in the study, including 15 nurses, three physicians, three patients, and two relatives of patients. Sampling was continued until saturation of the data (15).

2.2. Data collection

The main method of data collection was semi-structured interviews. First, the hospital’s nursing office was asked to provide a list of the telephone numbers of its ICCU nurses; then, the nurses were contacted and briefed on the objectives of the study. The dates of the interviews and their location were selected according to participants’ preferences. Interviews were conducted in the Department Head nurse’s office and during her absence. Interviews were conducted individually with participants with maximum variation in terms of work experience (total work experience in different departments, e.g., emergency, surgery, internal or dialysis departments, and ICCU work experience), age, culture, and social and economic background. During the interviews, the nurses were encouraged to share their experiences of providing nursing care, and they were asked, “What is competence in the ICCU?”, “What degree of competence is essential for working in the ICCU?”, “What skills do nurses use in the ICCU?”, “How do nurses use their skills and competence in clinical settings?”, and “What underlying factors are involved in nurses’ perception of their skills and competence?”. Subsequent follow-up questions continued according to the experiences described by participants to obtain in-depth information and clarify the concept under study. The participants were requested to provide subjective examples. Also, to move deeper into the interviews, probing questions were asked, such as, “What do you mean to convey? Please elaborate.” and “This is what I gathered from what you said, am I right to think that?”. The interviews lasted 40–90 minutes, depending on the circumstances and the willingness of each participant.

2.3. Data analysis

Collection and analysis of the data were conducted in accordance with the study’s objectives and the participants’ accounts of their experiences. The interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. To obtain a thorough understanding of the data, which is a crucial part of any qualitative study, the text of each interview was read several times, and the words, statements, and paragraphs extracted from the participants’ accounts of their experiences containing important points about competence in providing nursing care were determined as meaning units. Each meaning unit was marked on its relevant interview summary. The data were collected, coded, and analyzed simultaneously from the beginning of the study. Then, the data were broken into separate parts and examined for their similarities and differences and then reduced and condensed to form themes. In a second review, the emerged codes were compared based on their similarities and differences, and, then, similar codes were combined into one code. Categories were developed based on similarities and differences, and the data that were obtained raised questions about the phenomenon under study. The first step in the analysis of the data was conceptualization. The codes pertaining to the subject were assigned to a specific category, and a more objective conceptual title was assigned to it. Through coding and forming relationships between each category and its associated subcategories, the data formed new links with other data. To ensure the rigor of the codes, the categories were revised and compared again. Themes were identified by carefully considering and comparing the categories. Whenever a particular phenomenon was identified in the data, its concepts were categorized and analyzed using the content analysis method (18).

2.4. Rigor

The present study used the standard criteria of qualitative research. To ensure the validity and reliability of the data, data dependability, credibility, confirmability, and fitting were assessed. One of the best methods to increase the validity and reliability of data, which in qualitative research is construed as the study’s trustworthiness, is prolonged engagement of the researcher with the subject. In this study, the researcher interacted with the participants for over two decades as an instructor and instructor an ICCU as a trainer for nursing students. These measures helped the researcher better understand the experiences of the nurses and also to gain their trust. The present study used maximum variation sampling for the selection of its subjects, which helps with the fitting or transferability of the results; the participants who entered the study held different positions in hospitals and had diverse work experiences, ages, and cultural and economic backgrounds. For the credibility of the data, a member-check also was carried out. To that end, parts of the interview texts and emerged codes and categories were reviewed by the participants to assess the analytical processes and comment on their validity. The congruence of the ideas extracted by the researcher from the data was compared with participants’ comments and used in the coding stage to remove any ambiguities and to achieve the same concepts as provided by participants’ explanations. Data saturation also was used to increase the credibility of the data. Confirmability was ensured through audit trials, researchers’ impartiality, and the approval of three ICCU nurses who reviewed the interviews and codes, extracting similar codes and similar categorizations that were made in order to compare what the participants intended to communicate with what the researcher understood from their explanations. To determine the study’s confirmability and to audit its processes, the researcher carefully recorded and reported the stages and processes of the study to facilitate follow-up by others in the future. In addition to by the main researcher, the results also were examined and confirmed by three faculty members. Dependability of the results was ensured through immediate transcription of the interviews, the use of external checks, and the revision of the data. The transferability of the data was ensured by interviewing several different participants, quoting them directly, citing their examples, and expounding on the rich data obtained.

2.5. Ethical considerations

After obtaining a letter of introduction from the Ethics Committee of Semnan University of Medical Sciences, the participants were selected in compliance with the study inclusion criteria. Participants were briefed about the study’s objectives before beginning the interviews, and their permission was obtained for recoding the interviews. The participants were assured that the data would remain confidential, and they were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any point if they chose to do so. Written informed consent forms were obtained from all participants. The participants did not have to answer any questions that they felt uncomfortable about answering, and they were informed that they might be contacted again for further discussion, if necessary. They were also informed that they could get access to the study results if they wished to.

3. Results

Data from 23 interviewees were analyzed, and the interviewees consisted of 15 nurses (N), three physicians (D), three patients (P), and two patients’ relatives (PRs). The ages of the 15 nurses (14 females and one male) ranged from 26 to 45 (mean age of 35.2), and their work experience ranged from three to 24 years (mean of 8.73 years). Their experience in the ICCU ranged from one to 11 years (mean of 4.06 years). Two categories were extracted from the analysis of the data, including “clinical competence” and “professional competence.” Clinical competence included the sub-categories of “routine care,” “emergency care,” “care according to patients’ needs,” and “non-coronary patient care,” while professional competence included the sub-categories of “personal development,” “teamwork,” “professional ethics,” and “efficacy of nursing education” (Figure 1). The participants believed that clinical competence inferred performing routine nursing care, monitoring patients every minute, identifying their emergency conditions according to their needs, and occasional non-cardiac patient care, while professional competence was associated with their knowledge, skills, attitudes, professional ethics, and capabilities instilled through their nursing education.

Figure 1.

Nurses’ competence in Intensive Cardiac Care Unit

3.1. Clinical competence

Participants’ experiences showed that providing care based on clinical competence was the main essence and objective of nursing, i.e., preserving patients’ health.

3.1.1. Routine care

This type of care speeded up nursing interventions and led to greater savings in time, energy, and expenses and the optimal use of facilities and equipment. “In every ICCU shift, patients’ vital signs are monitored at least twice. As the drugs administered to them are mostly based on their [heart] rate and [blood] pressure, ECG is performed on three consecutive mornings” (N7).

3.1.2. Emergency care

Emergency care is essential in reducing mortality rates and cardiac complications. Performing emergency care is the responsibility of nurses that monitor patients. “When a patient needs CPR, the window of opportunity should not be lost, and atropine and adrenaline are injected and patients with VF are given a shock” (N6).

3.1.3. Care according to patient needs

Nurses believed that every patient requires his or her own particular care. “Some have coronary heart diseases, acute pulmonary edema, or corpulmonale. Health personnel should know how to care for all of them” (N4). “The patient is examined, and through establishing a good relationship with them, we find out how to care for him or her” (N8).

3.1.4. Non-cardiac patient care

The ICCU is designed specifically for treating coronary heart patients. Hospitalization of non-cardiac patients disrupts coronary patients’ peace and harms the quality of care provided to them. It causes several problems, including the patients’ mental disturbance, burdening nurses with overtime work, confusing doctors, and generally creating chaos in the ward. “Patients who have to continually be suctioned and constantly provided with urinals …, well, these have adverse effects on us” (P1). “There are 4 patients, 3 have respiratory conditions and require suction, gavage feeding and ABG monitoring; these procedures take time, and I cannot provide adequate care to coronary patients, which harms the patient” (N3).

3.2. Professional competence

Nurses were fully aware of the importance and necessity of professional competence, and they believed that the development of professional competence leads to the overall promotion of nursing as a profession. Professional competence included personal development, teamwork, professional ethics, and efficacy of nursing education.

3.2.1. Personal development

As for personal development, the nurses emphasized the need for knowledge and clinical skills. Life-threatening conditions of the patients, limited time resources, poor access to doctors, changes in medical/care programs, and potential errors due to the lack of adequate knowledge and skills were among the reasons for the nurses’ emphasis on personal development. “Care models require a greater focus on increased knowledge. The greater our knowledge is, the more of help it can be during the treatment of patients” (N3).

3.2.1.1 Having clinical skills

One of the factors discussed by participants for the category of professional competence and the sub-category of personal development was the possession of clinical skills. According to the participants, the different aspects of clinical skills included capabilities, professional motivation, interest in the profession, leadership skills, risk-taking characteristics, accountability, ability to maintain composure and patience, ability to make decisions, speed, accuracy, concentration, change, innovation, and creativity. “This is a critical unit. Nurses should have full knowledge of intubation. Compared to a novice, we should possess much greater skills” (N14).

3.2.1.2. Capabilities

As for nurses’ capabilities, one of the nurses stated: “Occasionally, the less experienced nurses set out to control blood vessels and serums at the beginning of a shift. Although IV lines are important, attending to a patient who has received CPR and whose life depends on dopamine and who is now low on dopamine is more urgent” (N12).

3.2.1.3. Work motivation

Motivation is considered an important factor in nurses’ desire for acquiring professional competence. “Not just any nurse should work in a ICCU; I made efforts, studied for a Master’s Degree. Their specialists and Master’s programs were good. Nurses should find motivation” (N11).

3.2.1.4. Interest in the profession

Interest in the profession and the desire to work in an ICCU encouraged the nurses to try twice as hard to gain professional competence. “An interest in the work leads nurses to make efforts for their patients. What happens if a nurse leaves her patients to their own for a minute?” (N8).

3.2.1.5 Leadership

Given the life-threatening conditions of patients, nurses’ leadership qualities in caring for them are highly important. “A nurse should determine which task takes priority right away. This is a teaching hospital, and occasionally the residents do not know about nursing triage” (N11).

3.2.1.6 Risk-taking characteristics

Competence encouraged nurses to be more involved in making decisions. Thus, they were able to show that they could propose good ideas and act upon them. “One patient had hypoxia, and the nurse suggested that the doctor order a Midazolam injection or give a shock –if it were me though, I would’ve merely rested with intubation” (D3).

3.2.1.7 Accountability

Accountability plays an essential role in performing professional duties. Health personnel’s efficacy depends on their level of responsibility within the organization. “With cardiac patients, the personnel should know how important the care provided to the patient actually is; when I order something for a patient, I can see that the nurses do their job whole-heartedly” (D1).

3.2.1.8 Maintaining composure and patience

One nurse argued for the importance of maintaining composure and patience in clinical settings. “A nurse should be calm, and not make a mountain out of a molehill during her shifts. Not to say anything in front of the patients to cause their anxiety and stress” (N5).

3.2.1.9 Ability to make decisions

Competence encourages personnel to participate more enthusiastically in making decisions. “As an experienced and conscientious person, a nurse should be able to inform the doctor if a patient is showing indications for ICU admission and argue why he has been brought to the ICCU, or the patient has been brought to the ICU, must be admitting to ICCU and streptokinase (SK) might need to be administered too” (N11).

3.2.1.10 Speed and rapid responsiveness

Participants considered rapid responsiveness by the personnel to be an important factor. “Nurses should be quick at preparing the necessary equipment and bringing in medications. All this is possible when the nurse is an expert” (D1).

3.2.1.11 Precision and concentration

Two essential aspects of the clinical skills of ICCU nurses are precision and concentration. “Nursing requires precision. There were two patients with the same last names but different first names. A urine test taken was taught to belong to the wrong patient, and he took antibiotics for two days before revealing that he had in fact never taken a urinalysis (UA)” (N1).

3.2.1.12 Change, innovation, and creativity

Highly-motivated and skilled nurses tended to be more creative. “We should decide on the spot what we can do for the patient and then provide innovative care at the desired level” (N12).

3.2.2. Teamwork

Teamwork was an important factor in professional competence. Most nurses worked as a team when the clinical conditions of a patient were really bad, and they helped each other perform Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), especially when the nurse in charge had little experience, and the patient’s life depended on receiving full, professional care. Influencing factors of teamwork include good cooperation, good communication abilities, and experience.

3.2.2.1 Good cooperation

Most nurses in the ICCU were happy with the cooperation of other nurses. “Just now, a patient with myocardial infarction (MI) came in and was administered SK. A nurse who was working with me monitored the patient. Turns out he also had hypotension. I was administering the drugs and the serum” (N5).

3.2.2.2 Good communication abilities

The participants believed that communication was an essential element of teamwork in performing highly complex duties. “Special conditions of the patients admitted and performing advanced care have resulted in the formation of a good relationship among nurses” (D1).

3.2.2.3 Having experience

Acquiring experience is an effective aspect of teamwork and professional competence.

“I always ask my colleagues how many years they’ve been working in ICCU and they always eagerly explain it to me; not just to me, to everybody” (N2).

3.2.3 Professional ethics

Nurses were always trying to perform their duties in compliance with the principles of professional nursing ethics.

3.2.3.1 Faith in God

Nurses consider God always to be watching them, and they believe they should perform patient care with that knowledge in mind. “We have a responsibility toward the patient, and before God; so we should do our job for the sake of God’s satisfaction” (N3).

3.2.3.2. Having a work conscience

Nurses believe that providing quality care is subject to the involvement of a person’s conscience. “The bottle of Amiodarone drops off the table and breaks; it is half past three in the morning; no one finds out. Either you have a conscience and replace it, or administer two instead of three shots, with a reduced effect” (N1).

3.2.3.3. Self-confidence

Having self-confidence plays an important role in competence when providing care to patients. “Certain unit tasks require self-confidence, and the lack of self-confidence might lead to errors and harm the patient and the nurse” (N12).

3.2.4. Efficacy of nursing education

Nursing education provides learners with the basic knowledge and fundamental skills of performing professional duties. “A nursing trainer should have adequate ethical and scientific prowess and skills, so that nursing students can learn from him the ability to properly perform their professional duties in the future” (D2).

4. Discussion

The results of this study showed that competence in nursing in the ICCU involves both clinical and professional competence. The clinical aspect of competence in nursing also emerged in the findings of other studies that had examined intensive care nursing (7, 19, 20). Aari et al. (2008) considered nursing interventions, basic care, understanding humans’ physical and psychological functions, and monitoring patients as part of clinical competence in intensive care nursing (7). The findings of this study showed that recognizing the critical conditions of patients and performing emergency care are part of clinical competence. Detecting abnormal conditions in critical care nursing also is part of clinical competence in nursing (19, 20). The results of the study showed that clinical competence is partly about recognizing patients’ needs and then providing nursing care according to those needs. Special care is a key concept in nursing (21). Special nursing care is the design of nursing care in accordance with the needs of a patient at a specific time frame (22). The results of the study also showed that patients, nurses, and doctors were unhappy about the hospitalization of non-cardiac patients in the ICCU. Aari et al. (2008) posited that patients’ comfort is part of clinical competence (7). Hospitalization of non-cardiac patients in CCUs reduces the quality of care provided in these units and increases the possibility of the occurrence of accidents (23).

The results also indicated that professional competence was a part of competence. The development and standardization of different aspects of competence are necessary in nursing (24, 25). Personal development is part of professional competence. Aari et al. (2008) posited that “the majority of studies have emphasized personal development as the most important part of nursing competence in special care units” (7). Jamieson et al. (2002) wrote, “Special care nurses are eager to achieve personal development” (26). Personal development is dictated by the need to acquire knowledge, which remains an essential component of nursing and improves problem-solving skills as well as the quality of care (27). Knowledge is the key to promoting professional competence (28). Personal development also is dictated by the need to acquire more professional skills. Competence is comprised of the knowledge, skills, and abilities required for delivering a specific level of care (29). One aspect of professional skills is the empowerment of nurses. Kuokkanen et al. (2002) discussed the need for the empowerment of CCU nurses (10). Empowered nurses have increased motivation, self-confidence, and autonomy in responding to questions and programs and making decisions through their accountability and having an active participation in clinical learning (30). Motivation also is a major determinant of professional skills. Lee-Hsieh et al. (2003) described motivation as crucial to effective performance in nursing (31). Some studies have suggested that motivation is an aspect of competence, while others have proposed that it is merely an influencing factor of competence (3, 32–34). Motivation affects management, knowledge, skills, attitudes, and communication (35). Interest in the profession also affects the acquiring of professional skills. Nurses who are interested in their profession enjoy a higher degree of motivation. Another aspect of professional skills is leadership. Members of a health team who tend to be more professional and skilled play a key role in preventing clinical accidents (23). The results also showed that nurses’ risk-taking characteristics are another determinant of professional skills. CCU nurses can extend their area of functioning and make critical decisions (36). Accountability is another aspect of professional skills and an effective contributor to professional competence that requires nurses’ motivation as well as their knowledge and experience (34). Taking responsibility is a care duty of nurses (37). The results of the study also showed that nurses’ ability to make decisions is an aspect of professional skills and a part of their overall professional competence (7). Clinical decisions are made according to the most advanced technologies available, the rapid changes in the patient’s conditions, and the specialized knowledge of the personnel (38, 39). The results of the study also showed that nurses’ precision is another aspect of their professional skills. Carelessness of nurses can result in economic damage and possibly even the death of a patient (40). Another aspect of professional skills is nurses’ willingness to be innovative. The ability to design and plan, think critically, effect change, promote personal development, increase information technology, and work with advanced systems are examples of professional competence (34).

The results of the study also showed that teamwork is part of professional competence. Teamwork is a solution for coping with shortages of personnel and finances, increased patient expectations, and medical errors (41). Cooperation among nurses is an important aspect of professional skills in teamwork. Members of special care groups interact with one another to achieve clinical objectives, set professional boundaries, and create new complex systems. Cooperation is part of competence (42). One of the aspects of professional skills in teamwork is communication between the nurses. Communication is essential to good team performance (43). Another aspect of professional skills in teamwork is the experiences of nurses, which promotes the will to learn among colleagues and consequently improves the quality of care (44). The results also showed that professional ethics is part of professional competence. Intensive care nurses are faced with sensitive ethical dilemmas (7). They require ethical knowledge and principles to make their decisions accordingly (45). An aspect of professional competence in professional ethics is faith in God. Galvin et al. (2006) believed that faith in God makes nursing care easier and more meaningful (46). The self-confidence of nurses is another aspect of professional competence in professional ethics. Competent nurses are confident that they can provide optimal care to their patients (47). The results also showed that part of professional competence is the efficacy of nursing education. An education that emphasizes learning and enhancing the students’ skills is rooted in the accurate analysis of professional duties and is responsible for improving the students’ knowledge, attitudes, and skills for aiding an excellent performance of professional duties in the future. Clinical nursing teachers ought to possess four important features, i.e., professional competence, interpersonal communication, a personality suitable for nursing, and the ability to teach (48), and they also should equip their students with the required competence for providing safe, quality clinical care according to clinical evidence (28).

5. Conclusions

The results of the present study revealed several dimensions for competence in ICCU nurses. Having competence leads to an improved quality of patient care and an increased patient satisfaction with the nurses and helps promote nursing as a profession and improve nursing education and clinical nursing.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the Vice Chancellor of Research and Technology of Semnan University of Medical Sciences for supporting the implementation of this research project and funding it. We also thank the staff of the Clinical Research Development Unit of Kowsar Educational, Research, and Therapeutic Center of Semnan University of Medical Sciences for providing the facilities that were used to do this work. Also, the author appreciates all of the participants (nurses and physicians at Kowsar (Fatemieh) Hospital ICCU, patients, and their relatives) who made this study possible.

Footnotes

iThenticate screening: March 01, 2016, English editing: April 16, 2016, Quality control: May 02, 2016

Conflict of Interest: There is no conflict of interest to be declared.

References

- 1.Dunn SV, Lawson D, Robertson S, Underwood M, Clark R, Valentine T, et al. The development of competency standards for specialist critical care nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2000;31(2):339–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meretoja R, Leino-Kilpi H. Instruments for evaluating nurse competence. J Nurs Adm. 2001;31(7–8):346–52. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200107000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meretoja R, Leino-Kilpi H. Comparison of competence assessments made by nurse managers and practising nurses. J Nurs Manag. 2003;11(6):404–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2834.2003.00413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meretoja R, Leino-Kilpi H, Kaira AM. Comparison of nurse competence in different hospital work environments. J Nurs Manag. 2004;12(5):329–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2004.00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meretoja R, Isoaho H, Leino-Kilpi H. Nurse competence scale: development and psychometric testing. J Adv Nurs. 2004;47(2):124–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cowan DT, Norman I, Coopamah VP. Competence in nursing practice: a controversial concept--a focused review of literature. Nurse Educ Today. 2005;25(5):355–62. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aäri RL, Tarja S, Helena LK. Competence in intensive and critical care nursing: a literature review. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2008;24(2):78–89. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bench S, Crowe D, Day T, Jones M, Wilebore S. Developing a competency framework for critical care to match patient need. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2003;19(3):136–42. doi: 10.1016/s0964-3397(03)00030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reischman RR. Critical care cardiovascular nurse expert and novice diagnostic cue utilization. J Adv Nurs. 2002;39(1):24–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.02239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuokkanen L, Leino-Kilpi H, Katajisto J. Do nurses feel empowered? Nurses’ assessments of their own qualities and performance with regard to nurse empowerment. J Prof Nurs. 2002;18(6):328–35. doi: 10.1053/jpnu.2002.130245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loftin C, Hartin V, Branson M, Reyes H. Measures of cultural competence in nurses: an integrative review. Scientific World Journal. 2013;2013:289101. doi: 10.1155/2013/289101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Currie V, Harvey G, West E, McKenna H, Keeney S. Relationship between quality of care, staffing levels, skill mix and nurse autonomy: literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2005;51(1):73–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Speziale H, Carpenter D. Qualitative research in nursing: Advancing the humanistic imperative. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Streubert HJ, Carpenter DR. Qualitative Research in Nursing: Advancing the Humanistic Imperative. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Polit DF, Beck CT. Essential of Nursing Research. 6ed. Lippincott Williams Wilkins Co; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adib Hajbaqry M. Grand Theory Methods. Tehran: Boshra; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105–12. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giuliano KK, Kleinpell R. The use of common continuous monitoring parameters: a quality indicator for critically ill patients with sepsis. AACN Clin Issues. 2005;16(2):140–8. doi: 10.1097/00044067-200504000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGhee BH, Woods SL. Critical care nurses’ knowledge of arterial pressure monitoring. Am J Crit Care. 2001;10(1):43–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suhonen R, Välimäki M, Leino-Kilpi H. The driving and restraining forces that promote and impede the implementation of individualised nursing care: a literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46(12):1637–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Radwin LE, Alster K. Individualized nursing care: an empirically generated definition. Int Nurs Rev. 2002;49(1):54–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1466-7657.2002.00101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Driscoll A, Currey J, George M, Davidson PM. Changes in health service delivery for cardiac patients: Implications for workforce planning and patient outcomes. Aust Crit Care. 2013;26(2):55–7. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khomeiran RT, Yekta ZP, Kiger AM, Ahmadi F. Professional competence: factors described by nurses as influencing their development. Int Nurs Rev. 2006;53(1):66–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2006.00432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arcand LL, Neumann JA. Nursing competency assessment across the continuum of care. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2005;36(6):247–54. doi: 10.3928/0022-0124-20051101-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jamieson L, Williams LM, Dwyer T. The need for a new advanced nursing practice role for Australian adult critical care settings. Aust Crit Care. 2002;15(4):139–45. doi: 10.1016/S1036-7314(02)80028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meretoja R, Eriksson E, Leino-Kilpi H. Indicators for competent nursing practice. J Nurs Manag. 2002;10(2):95–102. doi: 10.1046/j.0966-0429.2001.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lekan DA, Corazzini KN, Gilliss CL, Bailey DE. Clinical leadership development in accelerated baccalaureate nursing students: an education innovation. J Prof Nurs. 2011;27(4):202–14. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Force MV. The relationship between effective nurse managers and nursing retention. J Nurs Adm. 2005;35(7–8):336–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saarikoski M, Leino-Kilpi H. The clinical learning environment and supervision by staff nurses: developing the instrument. Int J Nurs Stud. 2002;39(3):259–67. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(01)00031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee-Hsieh J, Kao C, Kuo C, Tseng HF. Clinical nursing competence of RN-to-BSN students in a nursing concept-based curriculum in Taiwan. J Nurs Educ. 2003;42(12):536–45. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-20031201-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Issel LM, Baldwin KA, Lyons RL, Madamala K. Self-reported competency of public health nurses and faculty in Illinois. Public Health Nurs. 2006;23(2):168–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2006.230208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Calman L. Patients’ views of nurses’ competence. Nurse Educ Pract. 2006;6(6):411–7. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Memarian R, Salsali M, Vanaki Z, Ahmadi F, Hajizadeh E. Professional ethics as an important factor in clinical competency in nursing. Nurs Ethics. 2007;14(2):203–14. doi: 10.1177/0969733007073715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fasnacht PH. Creativity: a refinement of the concept for nursing practice. J Adv Nurs. 2003;41(2):195–202. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berner KH, Ives G, Astin F. Critical care nurses’ perceptions about their involvement in significant decisions regarding patient care. Aust Crit Care. 2004;17(3):123–31. doi: 10.1016/s1036-7314(04)80014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clancy A, Svensson T. ‘Faced’ with responsibility: Levinasian ethics and the challenges of responsibility in Norwegian public health nursing. Nurs Philos. 2007;8(3):158–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-769X.2007.00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Currey J, Botti M. The haemodynamic status of cardiac surgical patients in the initial 2-h recovery period. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2005;4(3):207–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Currey J, Botti M. The influence of patient complexity and nurses’ experience on haemodynamic decision-making following cardiac surgery. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2006;22(4):194–205. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ebrahimian AA. Night work nursing: the level of attention. Payesh. 2006;5(2):123–30. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thomas EJ, Sexton JB, Helmreich RL. Discrepant attitudes about teamwork among critical care nurses and physicians. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(3):956–9. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000056183.89175.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lingard L, Espin S, Evans C, Hawryluck L. The rules of the game: interprofessional collaboration on the intensive care unit team. Crit Care. 2004;8(6):R403–8. doi: 10.1186/cc2958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones ML. Role development and effective practice in specialist and advanced practice roles in acute hospital settings: systematic review and meta-synthesis. J Adv Nurs. 2005;49(2):191–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Darvas JA, Hawkins LG. What makes a good intensive care unit: a nursing perspective. Aust Crit Care. 2002;15(2):77–82. doi: 10.1016/S1036-7314(02)80010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liaschenko J, Peter E. Nursing ethics and conceptualizations of nursing: profession, practice and work. J Adv Nurs. 2004;46(5):488–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Galvin K, Emami A, Dahlberg K, Bach S, Ekebergh M, Rosser E, et al. WITHDRAWN: Challenges for future caring science research: A response to Hallberg (2006) Int J Nurs Stud. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.200802.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gohery P, Meaney T. Nurses’ role transition from the clinical ward environment to the critical care environment. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Robinson JA, Flynn V, Canavan K, Cerreta S, Krivak L. Evaluating your educational plan: Are you meeting the needs of nurses? J Nurses Staff Dev. 2006;22(2):65–9. doi: 10.1097/00124645-200603000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]