Abstract

Objective

We use the latest data to explore multiple dimensions of financial burden among children with special health care needs (CSHCN) and their families in 2009–2010 and changes since 2001.

Methods

Five burden indicators were assessed using the 2001 and 2009–2010 National Surveys of CSHCN: past-year health-related out-of-pocket expenses of ≥$1,000 or ≥3% of household income; perceived financial problems; changes in family employment; and >10 hours of weekly care provision/coordination. Unadjusted and adjusted prevalence estimates were used to assess burden in 2009–2010 and calculate absolute and relative measures of change since 2001. Prevalence rate ratios for each burden type in 2009–2010 compared to 2001 were estimated by logistic regression.

Results

Nearly half of CSHCN and their families experienced some form of burden in 2009–2010. The percentage of CSHCN living in families that paid ≥$1,000 or ≥3% of household income out of pocket for health care rose 120% and 35%, respectively, between 2001 and 2009–2010, while the prevalence of caregiving and employment burdens declined. Relative to 2001, in 2009–2010, CSHCN who were privately insured or least affected by their conditions were 1.7 times as likely to live in families that paid ≥3% of household income out of pocket, while publicly insured children were 20% less likely to do so and those most severely affected were 12% more likely to do so.

Conclusions

Over the past decade, increases in financial burden and declines in employment and caregiving burdens were observed for CSHCN families. Public insurance expansions may have buffered increases in financial burden, yet disparities persist.

Keywords: children with special health care needs, family burden, financial burden, trends

Special health care needs (SHCN) among children have been associated with financial and related nonfinancial consequences for the families that care for them. The impacts of organizing, providing, and financing care for children with special health care needs (CSHCN) can be direct, ie, high out-of-pocket spending for health services, or indirect through caregiving responsibilities which can adversely affect labor force participation. Families of CSHCN have been shown to have higher out-of-pocket health care expenses than typically developing children,1,2 with one recent estimate showing a more than 1-fold difference in annual expenditures.1 Special-needs families can also experience burden resulting from the effects of caregiving activities on employment resulting in unemployment,3,4 absenteeism from work,4,5 and conflicts between caregiving and work-related responsibilities.6 Caregiving can also adversely impact parents’ physical and mental health4,5 which may indirectly compromise their ability to engage fully in the labor force.7

Children with chronic health conditions and SHCN comprise a sizable and growing segment of the US pediatric population. According to the 2009–2010 National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs (NS-CSHCN), 15.1% of children <18 years of age have a SHCN.8 This reflects a nearly 18% increase since 2001, when 12.8% of children were estimated to have such needs. The Health Resources and Services Administration’s (HRSA) Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB) defines CSHCN as those with a chronic physical, developmental, behavioral, or emotional condition that has lasted or is expected to last 12 months or longer which results in functional limitations and/or requires health and related services beyond those generally required.9

Data from previous NS-CSHCNs have been used to provide point-in-time estimates of financial and related nonfinancial burden experienced by special-needs families among the population as a whole10 and among subpopulations, including those whose children have autism,11 Down syndrome,12 medically complex conditions,13 and low-income families.14 Additionally, although previous research has assessed changes over time in out-of-pocket expenses,1,15,16 these studies have focused solely on objective measures of family financial burden. No study, to our knowledge, has addressed multiple dimensions of financial and related nonfinancial burden among families of CSHCN over the last decade.

The NS-CSHCN is the only nationally representative data source capturing information on such measures among special-needs families. As such, the aims of this study were threefold: 1) to assess the prevalence of CSHCN whose families experienced financial and related nonfinancial burden in 2009–2010; 2) to determine whether the proportion of CSHCN whose families experienced these types of burden changed between 2001 and 2009–2010; and 3) to identify factors associated with any observed changes in the prevalence of such burdens.

Methods

Data were obtained from the 2001 and 2009–2010 NS-CSHCN.17 With direction and funding from HRSA MCHB, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics conducted the NS-CSHCN. The NS-CSHCN is a list-assisted random-digit-dial telephone survey, fielded through the State and Local Area Integrated Telephone Survey mechanism, which is designed to provide both national and state-level estimates of the prevalence and impact of SHCNs among US children and families. In 2009–2010, the sampling frame included both landline and cell phone numbers; in 2001, when the size of the wireless-only population was negligible, the sampling frame only included landlines.18 The NS-CSHCN was also fielded in 2005–2006. These data were not utilized for this analysis because possible bias associated with undercoverage of cell phone–only or –mostly households in which approximately 8% of children lived in 2005–2006.19

Approximately 370,000 children <18 years old were screened for SHCNs each survey year, resulting in 38,866 and 40,243 completed CSHCN interviews in 2001 and 2009–2010, respectively. If the household contained multiple CSHCN, only one child was randomly selected to be the interview subject; a parent or guardian served as the respondent. The CSHCN interview completion rate was 97.6% in 2001 and 80.8% in 2009–2010, although the weighted overall response rate declined from 61.0% in 2001 to 25.5% in 2009–2010. Adjustments to sampling weights reduced the potential magnitude of nonresponse bias to less than 1 percentage point for most survey estimates.

Five measures of financial and related nonfinancial burden were assessed: Absolute and relative out-of-pocket expenses: families spent ≥$1,000 or ≥3% of household income out of pocket for health-related needs during the prior 12 months; Financial problems: the child’s condition or conditions caused financial problems for the family; Employment changes: a family member quit or cut back on work as a result of the child’s condition or conditions; and Caregiving burdens: a family member spent >10 hours providing or coordinating care in the past week. Out-of-pocket expenses (not including health insurance premiums or costs that were reimbursed by insurance or another source) were assessed on the basis of parent-reported expenditures ($0, $1–$249, $250–$500, $501–$999, $1,000–$5,000, and >$5,000). High absolute out-of-pocket burden was defined as past-year expenditures ≥$1,000. Relative out-of-pocket burden was calculated as follows. An out-of-pocket dollar amount was assigned to each observation using the midpoint of each expenditure category; for expenditures >$5000 the median out-of-pocket expenditure for children from the 2000 and 2009 Medical Expenditure Panel Surveys (MEPS) was used ($5997 and $6232, respectively). Median family income was assigned on the basis of household size, poverty level, and state of residence. Relative out-of-pocket burden was calculated as the ratio of expenditures to income; high relative out-of-pocket burden was defined as past-year expenditures ≥3% of income.14

Financial problems were assessed using a single dichotomous survey item, “Has [the child’s] health condition caused financial problems for your family?” Employment changes were measured using affirmative responses to either of 2 dichotomous survey items capturing whether a family member had cut down on hours or quit working as a result of the child’s condition or conditions. Caregiving burdens were measured using responses to 2 questions related to care provision and care coordination, respectively. Respondents reported the number of hours that a family member engaged in each activity during the past week; responses were summed, and a cut-point of 11 hours was selected. A composite variable for any burden was constructed to capture the proportion of CSHCN experiencing any of 4 burdens historically tracked by HRSA MCHB20,21: high absolute out-of-pocket expenses, financial problems, employment changes, or caregiving burdens.

Seven sociodemographic and health-related variables were explored as possible covariates on the basis of previous research, a priori theory, and availability of equivalent measures in both surveys. Covariates included: child’s sex, child’s age,2,10,22 race/ethnicity,2,10,22 household poverty status,2,10 urban/rural residence,22 condition severity (reflecting both the frequency and extent of daily activity limitations),10,13 and insurance status and type.23

Bivariate and multivariable analyses were used to identify factors associated with family burden in 2009–2010 and to assess changes between 2001 and 2009–2010. Unadjusted prevalence estimates were calculated to describe the proportion of CSHCN whose families experienced each burden type. Change over the decade in the prevalence of each burden type was assessed through unadjusted and adjusted prevalence estimates at both time periods and the calculation of absolute and relative measures of change over the decade. Logistic regression was used to estimate adjusted prevalence rate ratios for each burden type in 2009–2010 compared to 2001, overall and by selected covariates. Interaction terms that crossed survey year with each covariate were included in separate models to assess relative differences over time in the experience of family burden by sociodemographic and health-related factors. As a result of missingness >5%, data were multiply imputed for cases with missing values for household income in both survey years and for race/ethnicity in 2009–2010. For all other variables, cases with missing data were omitted, resulting in 1% to 6% missing in multivariable models. Analyses were conducted by SAS 9.3 and SUDAAN 11.0.0 software (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC).

Results

Family Burden, 2009–2010

In 2009–2010, between 20% and 25% of CSHCN lived in families that experienced financial or employment burdens: paying ≥$1,000 out of pocket for health care services in the past year, experiencing financial problems, or having a family member quit or cut back on work. A smaller proportion, 13.1%, lived in families that spent >10 hours providing or coordinating care in the past week and 15.7% lived in families that spent≥3% of household income for past-year health care services (Table 1).

Table 1.

Prevalence of Selected Indicators of Family Financial Burden Among Families With CSHCN, by Sociodemographic and Health-Related Characteristics, 2009–2010 National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs

| CSHCN and Family Characteristics |

Paid ≥ $1000 Out of Pocket in the Past 12 Months |

Family Experienced Financial Problems |

Family Members Quit/Cut Back Work |

Family Members Spent >10 Hours Providing or Coordinating Care in the Past Week |

Any Financial or Nonfinancial Burden† |

Paid ≥3% of Income in the Past 12 Months |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | |

| Total | 22.1 | 0.35 | 21.6 | 0.39 | 25.0 | 0.42 | 13.1 | 0.34 | 48.1 | 0.47 | 15.7 | 0.32 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 21.5 | 0.44 | 22.4 | 0.53* | 26.4 | 0.55** | 13.7 | 0.46 | 48.7 | 0.61 | 15.3 | 0.39 |

| Female | 23.0 | 0.58 | 20.3 | 0.59 | 22.9 | 0.64 | 12.3 | 0.52 | 47.2 | 0.74 | 16.4 | 0.52 |

| Age | ||||||||||||

| 0–5 y | 18.6 | 0.74** | 19.3 | 0.83** | 30.5 | 0.99** | 19.4 | 0.91** | 50.2 | 1.07* | 13.8 | 0.67** |

| 6–11 y | 20.3 | 0.54 | 21.5 | 0.66 | 25.8 | 0.69 | 13.1 | 0.57 | 46.8 | 0.77 | 15.2 | 0.50 |

| 12–17 y | 25.6 | 0.58 | 22.7 | 0.61 | 21.4 | 0.60 | 9.9 | 0.44 | 48.2 | 0.72 | 17.3 | 0.51 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| Hispanic | 15.6 | 0.91** | 25.1 | 1.23** | 34.3 | 1.32** | 19.3 | 1.17** | 53.9 | 1.45** | 14.7 | 0.96** |

| Non-Hispanic white | 27.7 | 0.46 | 20.9 | 0.43 | 21.9 | 0.43 | 10.3 | 0.34 | 47.6 | 0.53 | 17.6 | 0.42 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 9.05 | 0.65 | 19.9 | 1.15 | 25.5 | 1.27 | 16.6 | 0.99 | 43.9 | 1.36 | 10.6 | 0.74 |

| Non-Hispanic other | 20.4 | 1.28 | 22.7 | 1.59 | 27.6 | 1.63 | 15.2 | 1.53 | 48.1 | 1.77 | 14.4 | 1.13 |

| Family structure | ||||||||||||

| Two parents, biological or adoptive | 27.5 | 0.49** | 20.2 | 0.48** | 23.8 | 0.5** | 11.0 | 0.40** | 48.3 | 0.59** | 15.6 | 0.40** |

| Two parents, step | 18.1 | 1.10 | 22.1 | 1.20 | 24.4 | 1.27 | 12.0 | 0.93 | 44.2 | 1.50 | 13.6 | 1.02 |

| Single mother | 14.8 | 0.64 | 24.8 | 0.91 | 29.3 | 0.99 | 17.2 | 0.82 | 50.6 | 1.05 | 18.2 | 0.72 |

| Other | 11.8 | 1.03 | 20.5 | 1.52 | 20.8 | 1.47 | 16.6 | 1.52 | 43.7 | 1.75 | 10.7 | 0.93 |

| Poverty | ||||||||||||

| ≤100% FPL‡ | 5.4 | 0.42** | 23.0 | 0.91** | 33.2 | 1.02** | 23.3 | 0.96** | 49.9 | 1.11* | 15.1 | 0.74** |

| >100–≤200% FPL | 14.4 | 0.66 | 25.2 | 0.98 | 28.8 | 1.05 | 16.0 | 0.78 | 48.6 | 1.11 | 16.0 | 0.70 |

| >200–≤400% FPL | 28.0 | 0.76 | 24.1 | 0.73 | 22.3 | 0.74 | 10.3 | 0.62 | 48.3 | 0.87 | 23.9 | 0.72 |

| >400% FPL | 35.8 | 0.78 | 14.9 | 0.62 | 18.1 | 0.65 | 6.0 | 0.45 | 46.1 | 0.84 | 7.6 | 0.47 |

| Household education | ||||||||||||

| Less than high school | 6.3 | 0.83** | 21.1 | 1.56 | 32.4 | 1.74** | 24.1 | 1.71** | 51.7 | 1.94* | 11.8 | 1.13** |

| High school | 10.2 | 0.60 | 20.1 | 0.99 | 26.1 | 1.04 | 18.2 | 0.89 | 45.5 | 1.19 | 13.6 | 0.72 |

| More than high school | 28.1 | 0.44 | 22.1 | 0.43 | 23.5 | 0.44 | 10.1 | 0.33 | 48.3 | 0.51 | 17.0 | 0.39 |

| Household language | ||||||||||||

| English | 23.1 | 0.37** | 20.9 | 0.39** | 23.7 | 0.42** | 12.4 | 0.34** | 47.2 | 0.47** | 16.1 | 0.34** |

| Something else | 9.0 | 1.01 | 30.8 | 2.26 | 42.5 | 2.23 | 24.2 | 2.10 | 61.6 | 2.25 | 10.9 | 1.24 |

| Urban/rural location§ | ||||||||||||

| Urban | 23.0 | 0.41** | 21.7 | 0.46 | 25.2 | 0.48 | 12.6 | 0.39** | 48.4 | 0.54 | 15.4 | 0.38* |

| Rural | 18.6 | 0.66 | 20.9 | 0.71 | 24.1 | 0.77 | 15.3 | 0.70 | 46.9 | 0.91 | 17.2 | 0.65 |

| Type of insurance | ||||||||||||

| Private | 32.3 | 0.53** | 19.0 | 0.46** | 17.4 | 0.44** | 6.2 | 0.32** | 45.3 | 0.59** | 17.5 | 0.43** |

| Public | 6.2 | 0.40 | 21.0 | 0.75 | 32.1 | 0.83 | 20.9 | 0.73 | 47.6 | 0.89 | 10.2 | 0.50 |

| Private + public | 16.1 | 1.18 | 27.2 | 1.61 | 38.7 | 1.69 | 25.7 | 1.65 | 55.4 | 1.75 | 16.3 | 1.23 |

| Other comprehensive | 39.4 | 2.50 | 25.1 | 2.14 | 23.1 | 2.17 | 8.9 | 1.50 | 56.6 | 2.88 | 27.2 | 2.20 |

| Uninsured | 30.2 | 2.37 | 47.6 | 2.86 | 36.4 | 2.92 | 15.2 | 2.00 | 70.8 | 2.46 | 34.0 | 2.49 |

| Frequency of activity limitations | ||||||||||||

| Never affected | 19.0 | 0.56** | 9.4 | 0.54** | 8.9 | 0.53** | 3.9 | 0.3** | 30.6 | 0.74** | 10.1 | 0.43** |

| Somewhat/sometimes affected | 22.3 | 0.55 | 20.5 | 0.58 | 23.6 | 0.63 | 10.0 | 0.48 | 47.7 | 0.74 | 15.5 | 0.48 |

| Frequently/a great deal affected | 25.9 | 0.75 | 38.5 | 0.92 | 47.3 | 0.94 | 29.3 | 0.92 | 70.9 | 0.88 | 23.0 | 0.76 |

Estimates are weighted to be representative of all non-institutionalized CSHCN aged 0 to 17 years in the US. CSHCN indicates children with special health care needs; SE, standard error; and FPL, federal poverty level.

P < .05,

P < .01, chi-square test of independence.

Any of the following 4 burdens: paid ≥$1000 out of pocket in the past 12 months; family experienced financial problems; family members quit/cut back work; or family members spent >10 hours providing or coordinating care in the past week.

The FPL for a family of 4 was $22,050 in 2009–2010.

Children’s areas of residence were classified according to the rural–urban commuting areas. Urban areas include metropolitan areas and surrounding towns from which commuters flow to an urban area.

Rural areas include large towns with populations of 10,000 to 49,999 and their surrounding areas and small or isolated rural areas including small towns with populations of 2,500 to 9,999 and their surrounding areas.

The proportion of CSHCN whose families experienced each burden type varied by sociodemographic and health-related characteristics. Older CSHCN (aged 12–17 years) were more likely to live in families with both high absolute and relative out-of-pocket expenses and financial problems, while younger CSHCN (aged 0–5 years) were more likely to live in families that experienced employment and caregiving burdens. Racial/ethnic differences were also observed; health care for non-Hispanic White CSHCN was most likely to cost ≥$1,000 or ≥3% of household income out of pocket, whereas health care for Hispanic CSHCN was most likely to result in employment burdens and perceived financial problems. Between one quarter and one third of poor CSHCN lived in families that experienced either caregiving or employment-related burdens, although only 5.4% of poor CSHCN lived in families that experienced high absolute out-of-pocket expenses; CSHCN living in families with household incomes of >200–≤400% FPL were most likely to report high relative out-of-pocket expenses.

The prevalence of family burden also varied by insurance status and type: uninsured and privately insured CSHCN were most likely to live in families with high absolute and relative out-of-pocket expenditures (17.5% to 34.0%), compared to 10% or less of publicly insured CSHCN. However, privately insured CSHCN were less likely than publicly insured or uninsured CSHCN to live in families that experienced employment and caregiving burdens. Uninsured CSHCN, in particular, were most likely to live in families that experienced high relative financial burden (34.0%), financial problems (47.6%), and over 70% experienced any burdens. Family burden also varied by the frequency and extent of activity limitations: 9.4% of CSHCN who were never/rarely affected lived in families that experienced financial problems compared to nearly 40% of CSHCN who were frequently/a great deal affected; similar patterns were observed for employment and caregiving burdens.

Changes in Family Burden Between 2001 and 2009–2010

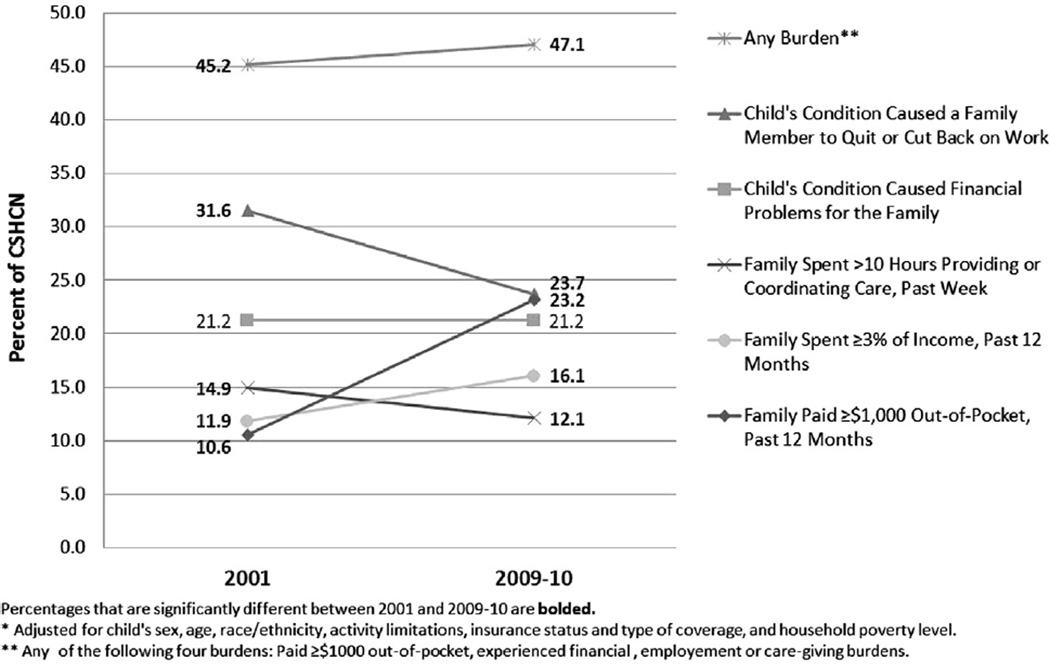

The proportion of CSHCN living in families that experienced financial and nonfinancial burden changed significantly over the past decade for 4 of the 5 indicators. The proportion of CSHCN living in families that paid high absolute out-of-pocket expenses more than doubled and the proportion experiencing high relative out-of-pocket expenses increased 35%, whereas employment and caregiving burdens declined slightly. No significant change was observed for financial problems (Figure).

Figure.

Adjusted* prevalence of selected measures of family burden, by survey year, 2001 and 2009–2010 National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs.

Compared to similar CSHCN, privately insured CSHCN were 1.7 times as likely to live in families that spent ≥3% of household income out of pocket on health care at the end of the decade whereas publicly insured children were 20% less likely to do so; no change was observed for uninsured children (Table 2). Privately insured children were also more likely to live in families that experienced financial problems by the end of the decade, while the reverse was true for publicly insured children. However, both publicly and privately insured CSHCN were less likely to live in families that experienced either employment or caregiving burdens by the end of the decade.

Table 2.

Adjusted Prevalence Rate Ratio of Experiencing Selected Measures of Family Burden in 2009–2010 Compared to 2001, 2001, and 2009–2010 National Surveys of Children With Special Health Care Needs

| CSHCN and Family Characteristics |

Paid ≥ $1000 Out of Pocket in the Past 12 Months (n = 77,147) |

Family Experienced Financial Problems (n = 77,806) |

Family Experienced Financial Problems (n = 77,806) |

Family Members Spent >10 Hours Providing or Coordinating Care in the Past Week (n = 75,502) |

Any Financial or Nonfinancial Burden† (n = 74,324) |

Paid ≥3% of Income in the Past 12 Months (n = 76,769) |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI | 95% CI | 95% CI | 95% CI | 95% CI | 95% CI | |||||||||||||

| RR | Upper | Lower | RR | Upper | Lower | RR | Upper | Lower | RR | Upper | Lower | RR | Upper | Lower | RR | Upper | Lower | |

| Total | 2.19* | 2.07 | 2.33 | 1.00* | 0.95 | 1.05 | 0.75* | 0.72 | 0.78 | 0.81* | 0.76 | 0.87 | 1.04* | 1.01 | 1.07 | 1.35* | 1.27 | 1.44 |

| Insurance type | ||||||||||||||||||

| Private insurance (2009–2010 vs 2001) | 2.50* | 2.34 | 2.66 | 1.13* | 1.06 | 1.21 | 0.72* | 0.68 | 0.77 | 0.79* | 0.70 | 0.89 | 1.18* | 1.14 | 1.23 | 1.73* | 1.61 | 1.86 |

| Public insurance (2009–2010 vs 2001) | 1.47* | 1.18 | 1.84 | 0.85* | 0.76 | 0.94 | 0.75* | 0.70 | 0.81 | 0.79* | 0.71 | 0.88 | 0.83* | 0.79 | 0.88 | 0.80* | 0.69 | 0.92 |

| Both private and public insurance (2009–2010 vs 2001) |

1.44* | 1.14 | 1.83 | 0.82* | 0.70 | 0.96 | 0.78* | 0.69 | 0.88 | 0.92 | 0.78 | 1.08 | 0.87* | 0.79 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.78 | 1.21 |

| Other comprehensive insurance (2009–2010 vs 2001) |

1.90* | 1.00 | 3.60 | 0.68 | 0.43 | 1.06 | 0.54* | 0.36 | 0.79 | 0.34* | 0.18 | 0.62 | 0.96 | 0.72 | 1.29 | 2.31* | 1.24 | 4.29 |

| Uninsured (2009–2010 vs 2001) | 1.49* | 1.20 | 1.85 | 1.07 | 0.90 | 1.26 | 0.88 | 0.73 | 1.07 | 0.80 | 0.57 | 1.12 | 1.11* | 1.01 | 1.23 | 1.06 | 0.86 | 1.30 |

| Activity limitations | ||||||||||||||||||

| Never/rarely affected (2009–2010 vs 2001) | 3.15* | 2.80 | 3.54 | 1.05 | 0.91 | 1.21 | 0.57* | 0.50 | 0.65 | 0.62* | 0.51 | 0.75 | 1.21* | 1.13 | 1.29 | 1.68* | 1.47 | 1.92 |

| Somewhat/sometimes affected (2009–2010 vs 2001) |

2.32* | 2.12 | 2.54 | 0.98 | 0.90 | 1.06 | 0.71* | 0.66 | 0.76 | 0.71* | 0.62 | 0.80 | 1.01 | 0.96 | 1.05 | 1.45* | 1.32 | 1.60 |

| Usually/always/a great deal affected (2009–2010 vs 2001) |

1.53* | 1.40 | 1.68 | 1.00 | 0.93 | 1.08 | 0.85* | 0.81 | 0.90 | 0.93 | 0.85 | 1.02 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 1.03 | 1.12* | 1.02 | 1.24 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||||||||

| Male (2009–2010 vs 2001) | 2.19* | 2.03 | 2.36 | 1.04 | 0.97 | 1.11 | 0.77* | 0.73 | 0.81 | 0.83* | 0.76 | 0.91 | 1.05* | 1.01 | 1.08 | 1.36* | 1.25 | 1.47 |

| Female (2009–2010 vs 2001) | 2.20* | 2.02 | 2.41 | 0.95 | 0.87 | 1.02 | 0.72* | 0.68 | 0.77 | 0.77* | 0.70 | 0.86 | 1.04* | 1.00 | 1.08 | 1.35* | 1.23 | 1.49 |

| Age | ||||||||||||||||||

| 0–5 y (2009–2010 vs 2001) | 1.86* | 1.64 | 2.13 | 0.86* | 0.77 | 0.97 | 0.70* | 0.65 | 0.75 | 0.76* | 0.68 | 0.86 | 0.91* | 0.86 | 0.96 | 1.08 | 0.94 | 1.24 |

| 6–11 y (2009–2010 vs 2001) | 2.25* | 2.04 | 2.47 | 1.05 | 0.97 | 1.14 | 0.75* | 0.71 | 0.80 | 0.83* | 0.74 | 0.93 | 1.02 | 0.98 | 1.07 | 1.37* | 1.24 | 1.52 |

| 12–17 y (2009–2010 vs 2001) | 2.30* | 2.11 | 2.50 | 1.02 | 0.95 | 1.10 | 0.79* | 0.74 | 0.85 | 0.83* | 0.73 | 0.94 | 1.15* | 1.10 | 1.20 | 1.48* | 1.35 | 1.63 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||||||||||

| Hispanic (2009–2010 vs 2001) | 1.73* | 1.38 | 2.17 | 0.99 | 0.85 | 1.15 | 0.72* | 0.65 | 0.80 | 1.00 | 0.82 | 1.22 | 0.97 | 0.89 | 1.05 | 1.04 | 0.86 | 1.25 |

| Non-Hispanic white (2009–2010 vs 2001) | 2.29* | 2.15 | 2.44 | 1.01 | 0.96 | 1.07 | 0.75* | 0.72 | 0.79 | 0.78* | 0.72 | 0.85 | 1.09* | 1.06 | 1.13 | 1.50* | 1.40 | 1.62 |

| Non-Hispanic black (2009–2010 vs 2001) | 2.52* | 1.93 | 3.30 | 1.02 | 0.87 | 1.20 | 0.77* | 0.68 | 0.87 | 0.78* | 0.66 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.85 | 1.02 | 1.11 | 0.9 | 1.36 |

| Non-Hispanic other (2009–2010 vs 2001) | 1.71* | 1.33 | 2.19 | 0.91 | 0.74 | 1.11 | 0.77* | 0.66 | 0.90 | 0.72* | 0.55 | 0.92 | 0.97 | 0.87 | 1.07 | 1.08 | 0.85 | 1.37 |

| Poverty level‡ | ||||||||||||||||||

| ≤100% FPL (2009–2010 vs 2001) | 1.28 | 0.97 | 1.67 | 0.85* | 0.76 | 0.95 | 0.74* | 0.67 | 0.81 | 0.85* | 0.74 | 0.96 | 0.86* | 0.81 | 0.92 | 0.70* | 0.62 | 0.80 |

| >100–≤200% FPL (2009–2010 vs 2001) | 2.02* | 1.74 | 2.34 | 0.91* | 0.82 | 1.00 | 0.71* | 0.65 | 0.78 | 0.70* | 0.61 | 0.80 | 0.89* | 0.84 | 0.95 | 1.40* | 1.24 | 1.58 |

| >200–≤400% FPL (2009–2010 vs 2001) | 2.45* | 2.22 | 2.70 | 1.10* | 1.02 | 1.19 | 0.77* | 0.71 | 0.83 | 0.86* | 0.75 | 0.98 | 1.11* | 1.06 | 1.17 | 2.10* | 1.90 | 2.33 |

| >400% FPL (2009–2010 vs 2001) | 2.25* | 2.06 | 2.47 | 1.17* | 1.03 | 1.33 | 0.79* | 0.72 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.73 | 1.04 | 1.24* | 1.18 | 1.31 | 1.28* | 1.08 | 1.52 |

Estimates are weighted to be representative of all non-institutionalized CSHCN aged 0 to 17 years in the US. CSHCN indicates children with special health care needs; RR, relative risk; CI, confidence interval; and FPL, federal poverty level.

Statistically significant changes from 2001 to 2009–2010.

Any of the following 4 burdens: paid ≥1000 out of pocket in the past 12 months; family experienced financial problems; family members quit/cut back work; or family members spent >10 hours providing or coordinating care in the past week.

The FPL for a family of four was $17,650 in 2001 and $22,050 in 2009–10.

An association was observed between activity limitations and changes in out-of-pocket expenses. Compared to similar CSHCN in 2001, CSHCN who were never/rarely affected by their condition or conditions in 2009–2010 were approximately 1.7 times as likely to live in families that paid high relative out-of-pocket expenses, while those who were most severely affected were 12% more likely to do so. Declines in employment-related burden were observed for all CSHCN, but varied by degree of activity limitations: those who were least affected were more than 40% less likely to experience this type of burden in 2009–2010 relative to 2001, whereas those who were most severely affected were 15% less likely to do so. Over time, less severely affected CSHCN were also less likely to live in families that experienced caregiving burdens, while no change was observed for the most severely affected CSHCN.

Discussion

This study estimated the prevalence of financial and related nonfinancial burden experienced by CSHCN and assessed changes over time in the likelihood of experiencing these burdens. Our results show that such burdens are common among CSHCN and their families with nearly half experiencing high absolute out-of-pocket expenses, financial problems, employment or caregiving burdens in 2009–2010. Sociodemographic and health-related patterns in family burden in 2009–2010 were similar to those previously reported10,20,21: high absolute out-of-pocket expenses were more common among older, nonHispanic White, privately insured CSHCN with higher incomes, while employment and caregiving burdens were more common among younger, Hispanic and nonHispanic Black publicly insured CSHCN with lower family incomes. Uninsurance and frequent activity limitations were associated with all burden types.

Increases in the proportion of CSHCN whose families experienced high absolute or relative out-of-pocket expenses are consistent with the overall increase in out-of-pocket health care spending during the last decade.24 We used both absolute and relative measures of financial burden to better address our stated aims of updating previously tracked family burden indicators8 while assessing changes over time after controlling for inflation and shifts in health care spending relative to income. Our findings for absolute burden differed from a recent analysis using MEPS, which reported that average absolute out-of-pocket expenses for privately insured CSHCN decreased during the recession and experienced no overall change from 2001 to 2009.1 Methodological differences, including inflation-adjustment and a lower prevalence of SHCN (10.3%), may help to explain this discrepancy. Our measure of relative financial burden offers a different perspective and suggests that out-of-pocket expenses have grown relative to household income reflecting an increasing source of burden among families of CSHCN.

The experience of this increased burden, however, was not uniform. We found that public insurance was associated with a smaller increase in absolute out-of-pocket expenses and significantly reduced relative out-of-pocket and perceived financial burdens in contrast to private coverage. These results suggest that public coverage may have shielded the most vulnerable families from this type of burden. If true, increases in out-of-pocket expenses may have been steeper without public insurance expansions; we observed larger increases in models that held demographic factors (including insurance) constant over time. The proportion of CSHCN with public insurance rose from 21.7% to 34.7% in the past decade.8 All other things being equal, if public coverage continues to expand as expected as a result of provisions in both the Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act (CHIPRA) and the Affordable Care Act,25 increases in out-of-pocket expenses and perceived financial burden should be lower than if this rise does not occur.

Despite a concurrent decline in the proportion of privately insured children, this type of coverage remains the most common for CSHCN. Provisions of the Affordable Care Act that eliminate practices which deny, limit, or rescind coverage and increase coverage of preventive services may result in out-of-pocket cost savings for families of privately insured CSHCN and increased access to health care coverage in general.26 However, as a result of exclusions for grandfathered or self-funded employer-sponsored plans, not all private plans will be subject to these reforms and benefits and burdens may continue to vary among special-needs families with private insurance.27 Of note, private plans lose their grandfathered status if significant changes are made that reduce benefits or increase costs to consumers in which case consumers gain new benefits such as increased coverage of preventive services. Further, state variation in what are considered essential health benefits may result in additional coverage gaps for some services, which could lead to variablity in family burden for CSHCN with private coverage purchased independently or through an exchange.28 The impact of protections codified by the health care law on special-needs families may be testable using data from future population-based surveys.

It is possible that the observed increase in the proportion of CSHCN whose families experienced high out-of-pocket expenses may be related to changes within the CSHCN population: a long-term epidemiological shift in pediatric chronic illness from physical conditions to those of an emotional, behavioral or developmental (EBD) nature.29 Previous research has shown families of children with EBD conditions to have higher health care costs30 and to be more likely to experience financial, employment and caregiving burdens than other chronically ill children, particularly those with private insurance coverage.31 Additional analyses controlling for the presence of a parent-reported emotional, behavioral, or mental health condition somewhat attenuated the risk for high absolute and relative out-of-pocket expenses overall and among privately insured CSHCN in particular (data available upon request). Although covered, behavioral health benefits are frequently restricted and subject to high cost-sharing requirements under private plans.32

Whether driven by external market forces or population-based shifts in the nature of pediatric chronic illness—or some combination therein—these results highlight a significant source of burden within the CSHCN community. Of note, prior analysis of high absolute out-of-pocket expenses suggests that this experience, alone, may not pose a significant barrier to service system access or reflect severe caregiving burdens overall.33 For this reason, we explored multiple measures of financial burden in the effort to draw a more complete picture of related challenges experienced by CSHCN and their families. We observed significant, albeit modest, declines in the proportion of families reporting employment and caregiving burdens. Improvements over time in both the identification and treatment of pediatric chronic illness could reduce the burden of care by reducing the impact of the conditions. However, we speculate that the observed declines in employment and caregiving burdens are rooted in the recent economic recession which may have left parents without the flexibility to forgo or reduce employment (and engage in extensive caregiving) for fear of not being able to find subsequent work. Given that unemployment peaked during the administration of the 2009–2010 survey, it is also possible that fewer caregivers had employment to quit or cut back on.34 Nonetheless, declines in employment and caregiving burden persisted and somewhat intensified after adjustment for increases in poverty and other demographic factors.

Finally, our results are consistent with previous research which found that family burden varied by condition severity,3,10,13 although the greater increase in both absolute and relative financial burden over the decade for families of less severely affected CSHCN was unexpected. It is possible that the 2-fold increase in the likelihood of high absolute out-of-pocket expenses among families of never/rarely affected CSHCN may reflect aforementioned shifts in condition type29 and the attendant inadequacy of insurance coverage for behavioral and mental health treatment.23,31 By contrast, families of less severely affected CSHCN experienced significant declines in the risk of employment or caregiving burden, while little or no change was observed in the risk of these burdens for the most severely affected children. Although this might be expected given the degree and severity of need among severely affected CSHCN, it highlights their persistent vulnerability despite medical advances. Systems-based interventions including care coordination and medical home have been shown to mitigate some of the impact of caregiving burdens.11 The Affordable Care Act includes provisions which encourage the adoption of the health home or patient-centered medical home model as a means of improving both access to primary care as well as the quality and coordination of health care.35 If successful, efforts to increase the adoption of this model may provide additional support for CSHCN and their families.

Our study has several limitations. First, all data were self-reported by caregivers without independent verification from some other source. Second, the wording of the item capturing out-of-pocket expenses changed slightly between survey years, prompting parents to include copayments and dental or vision care in their estimates of out-of-pocket payments in 2009–2010. As such, it is possible that some of the observed increase in this indictor was due to measurement effects. However, given the documented rise in out-of-pocket health care expenditures during this period, it is unlikely that our results are wholly attributable to this change. Third, the cross-sectional rather than longitudinal nature of the data does not necessarily reflect child-level changes in risk over time, although trends were adjusted for compositional shifts in the CSHCN population. Fourth, we utilized categorical measures of family income and expenditures to calculate relative out-of-pocket burden. Additional limitations include those associated with the use of a telephone survey mechanism including noncoverage of households without telephones and changes in the potential for nonresponse bias resulting from declining response rates over time. Finally, because we were not able to include family contributions to insurance premiums or health care costs for other family members (which have been shown to be higher among families of individuals with chronic illnesses) in our analyses, the proportion of families experiencing high levels of health-related financial burden may be underestimated.22

Conclusions

Financial and related nonfinancial burdens are common among CSHCN and their families, with sizeable variation by sociodemographic and health-related factors and changes over time. In sum, public insurance expansions may have buffered increases in financial burden among the most vulnerable families, while small but significant declines in employment and caregiving burdens were observed overall. Yet disparities remain particularly for the majority of CSHCN who are privately insured and face high levels of objective financial burden, and those with more severe activity limitations, as well as minority, low-income, and uninsured CSHCN whose families are most likely to experience financial and related nonfinancial burdens. Changes in the financing and delivery of care may hold the potential to mitigate some of this burden.

What’s New.

Nearly half of children with special health care needs and their families experienced financial burdens in 2009–2010. The proportion paying ≥$1,000 or ≥3% of household income out of pocket for health care rose 120% and 35%, respectively, between 2001 and 2009–2010, while the proportion experiencing caregiving or employment burdens declined.

Footnotes

The opinions expressed by authors do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the US Department of Health and Human Services or the authors’ affiliated institutions.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Karaca-Mandic P, Yoo SJ, Sommers BD. Recession led to a decline in out-of-pocket spending for children with special health care needs. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:1054–1062. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newacheck PW, Kim SE. A national profile of health care utilization and expenditures for children with special health care needs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:10–17. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuhlthau KA, Perrin JM. Child health status and parental employment. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:1346–1350. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.12.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuhlthau K, Kahn R, Hill KS, et al. The well-being of parental caregivers of children with activity limitations. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14:155–163. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0434-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Witt W, Gottlieb C, Hampton J, Litzelman K. The impact of childhood activity limitations on parental health, mental health, and workdays lost in the United States. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chung PJ, Garfield CF, Elliott MN, et al. Need for and use of family leave among parents of children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1047–e1055. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Altman BM, Cooper PF, Cunningham PJ. The case of disability in the family: impact on health care utilization and expenditures for nondisabled members. Milbank Q. 1999;77:39–75. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. Data resource center for child and adolescent health. [Accessed November 6, 2013]; Available at: http://childhealthdata.org/browse/survey. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bethell CD, Read D, Stein REK, et al. Identifying children with special health care needs: development and evaluation of a short screening instrument. Ambul Pediatr. 2002;2:38–48. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2002)002<0038:icwshc>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuhlthau K, Hill KS, Yucel R, Perrin JM. Financial burden for families of children with special health care needs. Matern Child Health J. 2005;9:207–218. doi: 10.1007/s10995-005-4870-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kogan MD, Strickland BB, Blumberg SJ, et al. A national profile of the health care experiences and family impact of autism spectrum disorder among children in the United States, 2005–2006. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e1149–e1158. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGrath RJ, Stransky ML, Cooley WC, Moeschler JB. National profile of children with Down syndrome: disease burden, access to care, and family impact. J Pediatr. 2011;159:535–540.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuo DZ, Cohen E, Agrawal R, et al. A national profile of caregiver challenges among more medically complex children with special health care needs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165:1020–1026. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parish SL, Shattuck PT, Rose RA. Financial burden of raising CSHCN: association with state policy choices. Pediatrics. 2009;124(suppl 4):S435–S442. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1255P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong ST, Galbraith A, Kim S, Newacheck PW. Disparities in the financial burden of children’s healthcare expenditures. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:1008–1013. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.11.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu H, Dick AW, Szilagyi PG. Does public insurance provide better financial protection against rising health care costs for families of children with special health care needs? Medical Care. 2008;46:1064–1070. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318185cdf2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Dept of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics. National survey of children with special health care needs. [Accessed September 30, 2013]; Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/slaits/cshcn.htm.

- 18.Blumberg SJ, Luke JV, Cynamon ML, Frankel MR. Recent trends in household telephone coverage in the United States. In: Lepkowski JM, Tucker C, Brick JM, et al., editors. Advances in Telephone Survey Methodology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2008. pp. 56–86. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blumberg SJ, Luke JV. Reevaluating the need for concern regarding noncoverage bias in landline surveys. AJPH. 2009;99:1806–1810. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.152835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.US Dept of Health and Human Services. Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau. The National Survey of Children With Special Health Care Needs Chartbook, 2001. Rockville, Md: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.US Dept of Health and Human Services. Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau. The National Survey of Children With Special Health Care Needs Chartbook, 2005–2006. Rockville, Md: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Witt W, Litzelman K, Mandic C, et al. Healthcare-related financial burden among families in the US: the role of childhood activity limitations and income. J Fam Econ Issues. 2011;32:308–326. doi: 10.1007/s10834-011-9253-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kogan MD, Newacheck PW, Honberg L, Strickland B. Association between underinsurance and access to care among children with special health care needs in the United States. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1162–1169. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.US Dept of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. National health expenditure data: historical. [Accessed September 3, 2013]; Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical.html.

- 25.The Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation, Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. Health coverage of children: the role of Medicaid and CHIP. [Accessed March 25, 2013]; Available at: http://www.kff.org/uninsured/upload/7698-06.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 26.US Dept of Health and Human Services. How the health care law benefits you. [Accessed November 6, 2013]; Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/facts/bystate/Making-a-Difference-National.html.

- 27.Association of Maternal and Child Health Programs. The Affordable Care Act and children and youth with autism spectrum disorders and other developmental disabilities. [Accessed November 6, 2013]; Available at: http://www.amchp.org/Policy-Advocacy/health-reform/resources/Documents/ACA_AutismFactSheet_5-3-12.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 28.McManus P. A Comparative Review of Essential Health Benefits Pertinent to Children in Large Federal, State, and Small Group Health Insurance Plans: Implications for Selecting State Benchmark Plans. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Halfon N, Houtrow A, Larson K, Newacheck PW. The changing landscape of disability in childhood. Future Child. 2012;22:13–42. doi: 10.1353/foc.2012.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guevara JP, Mandell DS, Rostain AL, et al. National estimates of health services expenditures for children with behavioral disorders: an analysis of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Pediatrics. 2003;112:e440–e446. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.6.e440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Busch SH, Barry CL. Mental health disorders in childhood: assessing the burden on families. Health Aff. 2007;26:1088–1095. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.4.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peters CP. Children With Special Health Care Needs: Minding the Gap. Washington, DC: George Washington Univeristy; 2005. National Health Policy Forum. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blumberg SJ, Carle AC. The well-being of the health care environment for CSHCN and their families: a latent variable approach. Pediatrics. 2009;124(suppl 4):S361–S367. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1255F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.US Dept of Labor, Bureau of Justice Statistics. Employment status of the civilian noninstitutional population, 1942 to date. [Accessed November 6, 2013]; Available at: http://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat01.pdf.

- 35.Abrams M, Nuzum R, Mika S, Lawlor G. Realizing health reform’s potential: how the Affordable Care Act will strengthen primary care and benefit patients, providers, and payers. [Accessed March 25, 2013];2011 http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Publications/Issue-Briefs/2011/Jan/Strengthen-Primary-Care.aspx. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]