Abstract

Purpose

Traumatic hip dislocation is an emergency. We studied their epidemiological, and therapeutic characteristics at Cotonou.

Methods

This was a retrospective study from 2006 to 2014 including all inpatient for traumatic hip dislocation, whose minimum follow-up was 12 months.

Results

Twenty-three cases in which 19 males were selected. The mean age was 39.6 years. It was mainly fracture-dislocations (17 cases). Sixteen dislocations were posterior. Reduction average delay was 41.0 h. The treatment was mainly orthopedic (16 cases). Few complications were noted: two osteoarthritis, one death. The functional results were excellent (8 cases), very good (4 cases) and good (8 cases).

Conclusion

Traumatic hip dislocations require early reduction to avoid complications.

Keywords: Traumatic hip dislocation, Reduction, Evolution

1. Introduction

Traumatic hip dislocations are serious injuries, resulting from high-energy trauma.1 The posterior dislocation is the most frequently met.2 The results of their treatment are not always satisfactory, with significant risk of developing osteoarthritis, which increases with the delay of the reduction.3, 4, 5 Tornetta quoted by Lima places the limit of this period at the sixth hour.6 For Brau, the decisive peak is that of the 12th hour after that, the occurrence of the avascular necrosis of femoral head increased from 15 to 47%.5 The aim of this work was to study the epidemiological, clinical and therapeutic characteristics of these lesions in the National reference center of Benin.

2. Patients and methods

This was a descriptive retrospective study of patients hospitalized for traumatic hip dislocation at Orthopaedic and Traumatology department at National Teaching Hospital of Cotonou from 1st January 2006 to 31st December 2014. Inclusion criteria were the occurrence of traumatic hip dislocation, the availability of a complete clinical and radiographic folder, and a minimum follow-up of 1 year. The availability of CT scan was not required. In fact, Cotonou is in a low-income country where there is not social security. Furthermore, CT scan costs a lot for the patients (121.95 Euros) and insurances take a longtime before giving a care provision. For each patient, we identified the following epidemiological parameters: gender, age and profession. Level of autonomy before the accident according to Parker,7 etiology and mechanism of the dislocation, delay of admission and the delay of reduction of the dislocation, signs in physical examination, and associated injuries were listed. The dislocations were classified into central, anterior, or posterior dislocation. The Epstein classification of anterior hip dislocations, the Thompson–Epstein classification of posterior hip dislocations and the Pipkin subclassification of Thompson–Epstein grade V fractures, were used.8 In case of acetabulum fracture, the pathological variety according to Judet and Letournel was specified.9 The type of reduction was noted as well as the realization or not of traction and its duration, regardless if the treatment is orthopedic or surgical. In case of surgery, the surgical approach and the gesture made were specified. The radiologic criteria after open reduction and internal fixation of the acetabular fracture were based on the gap remaining at the fracture site after reduction. It was anatomic (0–1 mm), good (2–3 mm), or poor (more than 3 mm) according to Matta.10 Any additional immobilization was notified. Functional results were evaluated according to Postel and Merle d’Aubigné score (PMA)11 at the last follow-up. Data were recorded with Epi Info 7.1.5 software, which allowed descriptive statistics in the form of numbers, percentage and average. Excel 2013 software has enabled the realization of tables and figures.

3. Results

3.1. Epidemiological aspects

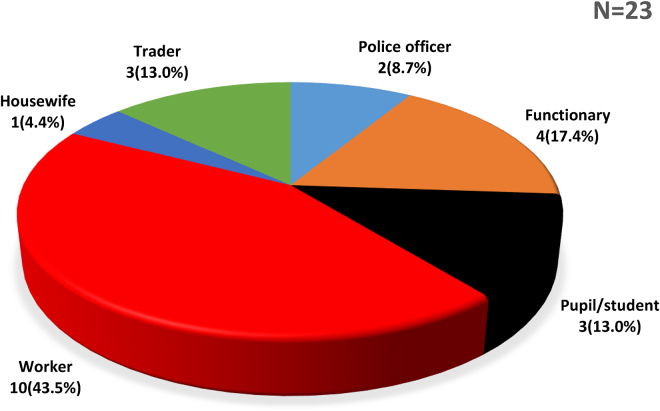

In 9 years, we collected 40 cases of traumatic hip dislocations among 4826 hospitalized patients, an incidence of 0.8% of hospitalizations. But only 23 files were selected. The average age of our patients was 39.6 years (18–70 years). Nineteen patients were male (82.6%) and 4 (17.4%) were female. The sex-ratio was 4.7. The workers were most affected (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of patient according to profession.

All patients were fully independent before the accident (Parker score = 9). Road-traffic accident was the main etiology: 20 cases out of 23 (86.9%). We noted 2 workplace accidents (8.7%), and 1 domestic accident (4.4%). Half of the road-traffic accidents were a collision between a motorcycle and a car. The most causal mechanism found was a fall on the knee in flexion in 9 cases (39.1%). The direct impact on the hip was found in 4 cases (17.4%) and the dashboard injury in 3 cases (13.0%). In 7 cases (30.5%) the mechanism could not be precisely presented.

3.2. Clinical aspects

The admission deadline average was 33.6 h (1 h – 20 days). Thirteen patients (56.6%) were seen before the 12th hour; 8 (34.7%) other patients before the 24th hour, and 2 after 24 h. The left hip was injured 14 times (61.0%) and the right 9 times (39.0%). On inspection, the hip was in extension, adduction, internal rotation in 18 cases (78.2%); an extension, abduction, and external rotation was observed in 1 case. The shortening was evident in 11 cases (47.7%) and ranged between 2 and 5 cm. One bridging of groin was found. Posterior dislocations (Fig. 2) were predominant: 16 cases on 23 (69.6%). Central dislocations are found in 6 cases (26.1%); one case (4.3%) of anterior dislocation type IC of Epstein was observed.

Fig. 2.

X-rays of a posterior dislocation before and after reduction.

Among the posterior dislocations, the most common type were type II of Thompson and Epstein (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of patients according to the type of posterior dislocation according to Thompson and Epstein classification.

| Number | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Type I | 06 | 37.50% |

| Type II | 07 | 43.75% |

| Type III | 01 | 06.25% |

| Type IV | 00 | 00.00% |

| Type V | 02 | 12.50% |

| Total | 16 | 100.00% |

All type V posterior hip dislocations were type IV of Pipkin. Eighteen patients (78.2%) introduced associated injuries detailed in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Distribution of associated injuries. C2: second cervical vertebra. C3: third cervical vertebra.

In 17 cases (73.9%), we had a hip fracture-dislocation and in 6 cases (26.1%) a pure dislocation. Acetabulum fractures were divided as follows: 8 posterior wall fractures, 3 bicolonne fractures, 4 transverse fractures, 1 anterior wall fracture and 1 anterior column-posterior hemitransverse. The CT scan performed in six patients allowed to detect intra-articular fragments, appreciate impaction of the femoral head which went unnoticed on X-rays.

3.3. Therapeutic aspects

All patients had received analgesics. The average delay of the reduction was 41.0 h (2 h – 21 days). The latter was always performed under general anesthesia. In 91.3% of patients, closed reduction was performed using the Allis maneuver. In the other cases (8.7%), an open reduction was required. The reduction was performed before the 12th hour in 8 cases (34.8%), in which 2 cases (8.7%) were done before the sixth hour. Eleven of the dislocations (47.8%) had been reduced between the 12th and the 24th hour, and 4 (17.4%), after the 24th hour. Twenty (87.0%) patients had received traction after the reduction. This was a waiting traction of osteosynthesis (6 cases) or traction as definitive orthopedic treatment (14 cases). The duration of the traction was 45 days in case of definitive orthopedic treatment. This traction was suspended before osteosynthesis. The final treatment was 16 times (69.6%) orthopedic and 7 times (30.4%) surgical. The latter consisted after the reduction in an osteosynthesis by posterior plate screwed of the acetabulum in 5 cases (a case of additional screwing of the anterior wall), and a screw of the femoral head in one case. Finally, the last patient (neglected dislocation-fracture) had immediately benefited of a total hip arthroplasty. The surgical approaches used were those of Kocher Langenbeck (5 cases), Senegas (1 case) and Moore (1 case). The average period before surgical care was 18 days (8–45 days). The reduction was judged satisfactory 3 times, and 2 times not satisfactory. A hip plaster immobilization was associated in 9 cases: 7 cases of orthopedic treatment and 2 cases of osteosynthesis judged unstable. Complications were found in 4 patients (17.4%). This was an infection around the pine of traction, two surgical site infections, a recurrent dislocation requiring the realization of a bony abutment, two avascular necroses of the femoral head, which had advanced to hip osteoarthritis. There was one case of death subsequent to hemorrhagic stroke anticoagulants at the 30th day of hospitalization.

The mean period of patients’ mobilization after the dislocation was 74 days (15–120 days).

The follow-up assessed in 22 patients, was in average of 53.5 months with range to 12 months (1 year) from 108 months (09 years). At his last follow-up of 18 months, one patient did not have fully supported due to the association of ipsilateral tibia fracture complicated with infected nonunion. The average range of full support for the remaining 21 patients was 125 days (90–180 days). PMA score was excellent, very good, good and bad respectively in 8 (36.4%), 4 (18.2%), 8 (36.4%) and 2 cases (9%).

4. Discussion

Our study presents some weaknesses that are its monocentric and retrospective character which make us retain the records of 23 patients.

4.1. Epidemiological aspects

The frequency of hip dislocation was 0.8% of hospitalizations, reflecting the scarcity of these lesions in our daily practice. These dislocations occurred usually in young adults (mean age = 39.6 years) male (82.6%). These results are similar to those of Abalo et al.,12 Onyemaechi and Eyichukwu13 and Lima et al.6 Road-traffic accidents (20 cases or 86.9%), implying a very high energy trauma were the main etiology in our study, which is in perfect agreement with literature.2, 6, 13 The severity of this injury can be attributed to increased accidents in high-speed motor vehicles, especially when seat belts are not worn. Indeed, the stability and the deep position of the hip explain the very high energy responsible for its dislocation. The dislocations occurring mainly in workers (43.5%), we could guess they fell victims of road traffic accidents while moving to their workplaces.

4.2. Clinical aspects

The average admission time in our series was 20 h (1 h – 7 days). Sometimes long, it is explained by the fact that some patients were initially oriented to peripheral centers, which referred them because of the insufficient technical platform. Another one left far away, in other area. The left hip was the most injured (61.0%). The same observation was made by Abdou Raouf and Allogo Obiang.14 The vicious attitude in extension, adduction, internal rotation, as well as shortening predominantly observed in our study are consistent with the large number of posterior dislocations found (16 or 69.6%). This anatomical variety is most common in literature.6, 12, 13 The violence of the causal trauma explains the high frequency of associated injuries (78.2% in our study). This rate is similar to the 74.4% of Lima et al.6 and 77% of Onyemaechi and Eyichukwu.13 The main associated lesion was acetabulum fracture (17 cases or 73.9%). The same observation was made by several authors.6, 12, 13, 14

Sciatic nerve paralysis found in 4 cases (17.4%) in our study had completely regressed. It was found in only 4% of cases in Onyemaechi and Eyichukwu's study13 and is usually due to either a compression or stretching either a racking nerve by a bony fragment.15

4.3. Therapeutic aspects

The delay of reduction is an important prognosis factor, which increases with the onset of post-traumatic osteoarthritis.5, 8 Although being an emergency, only 8 patients (34.8%) had performed a reduction before the 12th hour, in which 2 (8.7%) before the sixth hour. In the series of Onyemaechi and Eyichukwu, 73.5% of dislocations were reduced before the 12th hour.13 Our long delay could be due to the long time before admission of patients up to 7 days. The final treatment was mainly orthopedic: 69.6%. This treatment was also predominant in Abalo et al.,12 and Abdou Raouf and Allogo Obiang14 series. Indeed, the care of patients is at their own expense because of the absence of a social security system. Also, even when surgery was indicated, it was not often practiced on the poor patients. In literature, the association of a hip plaster immobilization after traction was not found. In our case, it allowed to immobilize the patient the time that acetabular lesions associated consolidate before charging. Unfortunately, they run the risk of hip stiffness inherent in plaster. At the last follow-up, the functional results were excellent, very good, and good respectively: 36.4%, 18.2% and 36.4% of cases. The two (9%) poor results were seen in those who developed post-necrotic hip osteoarthritis. Prognosis factors for this complication are the delay of reduction, the severity of the trauma and the importance of locoregional and general associated injuries.5, 6, 8 In our study, there was not an elevated number of avascular necrosis of femoral head. Radiographic findings for this complication usually appear within 2 years but can present as late as 5 years post-injury.8 The risk of osteoarthritis post-avascular necrosis of femoral head testifies of the value of regular radiographic monitoring for the early detection and an attempt to conservative treatment in young patients.8

5. Conclusion

Traumatic hip dislocations are more frequent in younger and male patients in our practice. Posterior type were predominant. Their reduction must be urgent, performed before the 12th hour whenever possible, to avoid complications which burden the functional prognosis.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Sah A.P., Marsh E. Traumatic simultaneous asymmetric hip dislocations and motor vehicle accidents. Orthopedics. 2008;31(6):613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deakin D.E., Porter K. Traumatic hip dislocation in adults. Trauma. 2009;11(3):189–197. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang R.S., Tsuang Y.H., Yang Y.S., Liu T.K. Traumatic dislocation of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;(265):218–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dreinhofer K.E., Schwarzkopf S.R., Haas N.P., Tscherne H. Isolated traumatic dislocation of the hip. Long term results in 50 patients. J Bone Jt Surg Br. 1994;76(1):6–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brau A.E. Traumatic dislocation of hip. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1962;44:1115–1134. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lima L.C., Nascimento R.A.L., Almeida V.M.T., Façanha Filho F.A.M. Epidemiology of traumatic hip dislocation in patients treated in Ceará, Brazil. Acta Ortop Bras. 2014;22(3):151–154. doi: 10.1590/1413-78522014220300883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parker M., Palmer C. A new mobility score for predicting mortality after hip fracture. J Bone Jt Surg Br. 1993;75:797–798. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.75B5.8376443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Obakponovwe O., Morell D., Ahmad M., Nunn T., Giannoudis P.V. Traumatic hip dislocation. Orthop Trauma. 2013;25(3):214–222. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Letournel E. Traitement chirurgical des fractures du cotyle. EMC Tech Chir Orthop Traumatol. 1991:1–30. [article 44-520] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matta J.M. Fractures of the acetabulum: accuracy of reduction and clinical results in patients managed operatively within three weeks after the injury. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1996;78:1632–1645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merle d’Aubigné R. Cotation chiffrée de la fonction de la hanche. Rev d Chir Orthop Réparatrice Appar Locomot. 1990;76:371–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abalo A., Tsolenyanu S.K., Dellanh Y., James Y.E., Walla A., Dossim A. Luxations traumatiques de la hanche: aspects épidémiologiques, thérapeutiques et évolutifs au CHU Sylvanus Olympio (CHU-SO) Journal de la Recherche Scientifique de l’Université de Lomé. 2013;15:419–425. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Onyemaechi N.O., Eyichukwu G.O. Traumatic hip dislocation at a regional trauma centre in Nigeria. Niger J Med. 2011;20(1):124–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdou Raouf O., Allogo Obiang J.J. Luxations traumatiques de hanche. Médecine d’Afrique Noire. 2006;53(11):591–596. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Decoulx P., Decoulx J., Duquennoy A. L’origine radiculaire des paralysies sciatiques par luxations-fractures de la hanche. Rev Chir Orthop Réparatrice Appar Locomot. 1974;60:259–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]