Abstract

Rationale

Young children of mothers with adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are at risk for ADHD by virtue of genetics and environmental factors. Moreover, parent ADHD is associated with maladaptive parenting and poor child behavioral treatment response. Thus, a combined approach consisting of behavioral parent training (BPT) and maternal stimulant medication (MSM) may be needed to effectively treat ADHD within families. However, providing combined BPT+MSM initially to all families may be unnecessarily burdensome since not all families likely need combined treatment. The purpose of this study is to examine how to combine, sequence, and personalize treatment for these multiplex families in order to yield benefits to both the parent and child, thereby impacting the course of child ADHD and disruptive behavior symptoms.

Study Design and Preliminary Experiences

This paper presents our rationale for, design of, and preliminary experiences (based on N = 26 participants) with an ongoing pilot Sequential Multiple Assessment Randomized Trial (SMART) designed to answer questions regarding the feasibility and acceptability of study protocols and interventions. This manuscript also describes how the subsequent full-scale SMART might change based on what is learned in the SMART pilot, and illustrates how the full-scale SMART could be used to inform clinical decision making about how to combine, sequence, and personalize treatment for complex children and families in which a parent has ADHD.

Keywords: adaptive interventions, parent ADHD, parent training

Rationale

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is highly familial, with heritability estimates exceeding .76 (Faraone et al., 2005). About half of adults with ADHD have at least one child with ADHD and 25–50% of children with ADHD have a parent with the disorder (Johnston, Mash, Miller, & Ninowski, 2012). Untreated ADHD in either the parent or child contributes to reciprocal negative family interactions (Johnston et al., 2012), as both parental and child ADHD are associated with family discord (Biederman, Faraone, & Monuteaux, 2002). Indeed, mothers with ADHD (or elevated ADHD symptoms) report and demonstrate in observational studies less involvement with their children, less positive parenting, less consistent discipline, poorer problem solving abilities, and less monitoring of their children's activities (Johnston et al., 2012). Although ADHD has a strong heritability component, a growing literature convincingly suggests that the quality of parenting is prospectively associated with ADHD severity and may moderate the persistence of ADHD and comorbid conditions (e.g., Chronis et al., 2007; Harold et al., 2013; Harvey, Metcalfe, Herbert, & Fanton, 2011; Molina et al., 2012). Thus, children of parents with ADHD are at both genetic and environmental risk (via sub-optimal parenting) for ADHD.

Moreover, parent ADHD may impact outcomes following evidence-based treatments for childhood ADHD, as both pharmacological and behavioral approaches require parents to obtain and consistently deliver treatment (Wang, Mazursky-Horowitz, & Chronis-Tuscano, 2014). Pharmacological treatments require parents to schedule and attend monthly appointments with the prescribing physician, obtain refills in advance of the prescription running out, and administer the medication daily or multiple times per day (Chronis-Tuscano & Stein, 2012). Behavioral parent training (BPT), grounded in operant conditioning and social learning theory, requires parents to closely monitor children while maintaining consistent household structure/routines, and use positive reinforcement and nonphysical (rather than harsh or reactive) discipline. Proper implementation and adherence to both evidence-based treatment modalities may be challenging for parents with ADHD due to performance deficits and other impairments common in adults with ADHD. It is therefore no surprise that parental ADHD has been found in many studies to predict diminished child behavioral treatment response (see Wang et al., 2014).

Theoretically, because parental ADHD is related to parenting difficulties and degree of benefit from behavioral parenting interventions, intervening with parents to reduce their adult ADHD symptoms holds the potential to improve parenting and child outcomes. To test this hypothesis, Chronis-Tuscano and colleagues (2008, 2010) examined the impact of methylphenidate extended release (OROS MPH) administered to 23 mothers with ADHD and evaluated effects on adult ADHD symptoms, parenting, and child behavior. In this sample, higher MPH doses (72-90 mg) were associated with improvements in maternal ADHD symptoms and self-reported parenting, but not on collateral reports of mothers’ parenting or observed parenting during analogue laboratory assessments (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2010). In contrast, Waxmonsky and colleagues (2014) reported that after eight weeks on optimal stimulant doses, parents with impairing levels of ADHD displayed improvements in observed parenting and child inappropriate behaviors. Thus, the evidence is mixed regarding the degree to which treating parents for their adult ADHD with stimulant medications can improve parenting and their children's behavior.

In both of these parental ADHD treatment studies, the majority of children were receiving stimulant medication prior to and during the trial. Therefore, the impact of treating ADHD in mothers first with stimulant medication prior to treating the child with stimulant medication or before teaching parenting skills remains unknown (Stein, in press). Early treatment of mothers could reduce the severity of child ADHD and externalizing behaviors over time and consequently, potentially delay the need for child stimulant medication. Delaying the need for stimulant medication is particularly important for young children for whom stimulants are less effective, associated with more side effects (Greenhill et al., 2006), and less acceptable to parents and physicians (Greenhill et al., 2006; Waschbusch et al., 2011; Wolraich, Bard, Stein, Rushton, & O'Connor, 2010). These aims are akin to secondary prevention efforts, where the goal is to intervene during the early emergence of a disorder by slowing the development or changing the trajectory of the disorder.

Given the mixed evidence regarding whether medicating parents with ADHD improves parenting and child outcomes, it stands to reason that early interventions aimed at improving parenting quality, to which young children with early ADHD symptoms might be particularly vulnerable, could potentially improve family functioning and child behavior (Healey, Gopin, Grossman, Campbell, & Halperin, 2010). Indeed, several studies of BPT for preschool ADHD have been conducted and have yielded positive outcomes (Charach et al. 2013). However, because ADHD in parents may be associated with a diminished response to BPT (Wang et al., 2014), a combined treatment approach directly targeting both maternal ADHD and parenting outcomes may be necessary for families in which both the mother and child have ADHD (or elevated ADHD symptoms). However, providing combined medication and parenting intervention to all mothers with ADHD as a first-stage treatment is burdensome (in terms of time, accessibility, and monetary cost) and, therefore, not feasible in real-world clinical practice.

The Need for Research on Sequencing Treatments in Mothers with ADHD

This suggests that a sequential approach to treatment may be necessary, whereby mothers are first treated with medication or parenting interventions and, in a second stage of treatment, mothers in need of additional treatment are provided combined medication and parenting intervention.

Jans and colleagues (2015) conducted the first randomized, multi-site, controlled trial aimed at understanding how best to treat mothers with ADHD using a sequence of treatments. In their study, 144 mothers of 6-12 year old children with ADHD1 were randomized to stimulant medication and group psychotherapy or supportive counseling (in a first stage of treatment), prior to both groups receiving BPT (in a second stage of treatment). Results indicated that, at 6-month follow-up, maternal psychopathology improved in the treatment group (in which mothers first received therapy and medication for their ADHD), but groups did not differ in children's externalizing behaviors following BPT. While this innovative study has several strengths, the research design limits knowledge regarding which modality to begin with (i.e., all participants received BPT in the second stage of treatment), for whom intensive and combined treatment is necessary, and which of the various child and parental treatment component(s) are active ingredients.

Presently, there are little data to guide the selection of whether to treat with medication or parenting intervention first, and for which families combined treatment is necessary, optimal, or in some cases contraindicated.

Sequential Multiple Assessment Randomized Trial (SMART)

The Sequential Multiple Assessment Randomized Trial (SMART) design optimally fits the examination of questions regarding sequencing of treatment in a manner designed to inform real-world clinical decision-making. The SMART design helps to answer clinically relevant questions, such as the following, concerning how best to sequence treatments: “Should treatment begin with targeting mothers’ ADHD symptoms with medication vs. begin with targeting maternal parenting with behavioral therapy?” and “Following initial treatment, is it better to use combined treatment (consisting of both maternal stimulant medication and behavioral parent training) vs. continuing the initial treatment (maternal medication or behavior therapy)?” Additionally, SMARTs could be used to answer questions to inform how best to individualize the sequences of treatments, for example, “For which families is it best to begin with medication vs. a behavioral parenting intervention?” and “Following initial treatment, for which families is it best to use combined treatment vs. continue the initial treatment?” Empirically determining when and how best to combine mother and child treatment has potential to improve parenting and child behavior in families in which the mother has ADHD.

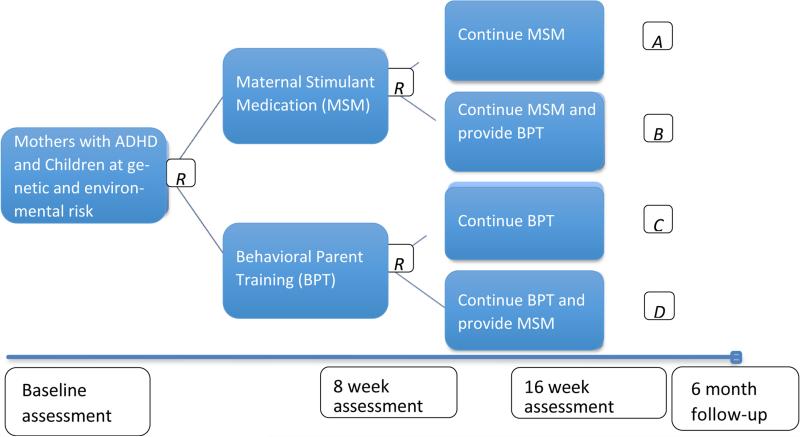

In our SMART (see Figure 1 for study design), we ultimately seek to answer the above key questions in order to guide clinical treatment of families in which the mother of a young child has ADHD. First, should treatment begin with medicating the mother or teaching her behavioral parenting skills? It makes theoretical sense to first medicate parents to improve uptake and consistency of behavioral parenting skills, but this approach may be less acceptable to parents who are seeking treatment for their children. Next, the SMART design will allow us to examine whether it is better to implement the first-line treatment over a longer duration (with as-needed modifications, such as organizational skills in combination with behavioral parent training) or to add the alternative treatment approach. Third, our SMART can address for whom it is better to begin with MSM or BPT in Phase 1 based on baseline clinical characteristics such as comorbid conditions, education level, child ADHD symptom severity. Fourth, our SMART can address for whom it is better to continue or combine treatments in Phase 2 based on treatment provided in Phase 1 as well as outcome of Phase 1 treatment such as adherence, early response/non-response. In sum, conducting a SMART trial will allow us to determine how best to design, adapt, and personalize interventions for families in which the mother has ADHD and her young child who is also displaying ADHD symptoms, but has not yet been treated (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study Schematic

Given the novelty of treating mothers first and the potential complexities inherent in sequencing treatments in this population, we are currently in the process of conducting a pilot SMART (Almirall, Compton, Gunlicks-Stoessel, Duan, & Murphy, 2012) to develop, refine and demonstrate acceptability and feasibility of all treatments and study protocols prior to embarking on the full-scale SMART. For example, we are evaluating participants’ and providers’ perceptions of the acceptability and feasibility of medication and behavioral parent training interventions, including the acceptability of moving from first- to second-line treatments within the SMART protocol. We are also developing and piloting guidelines for second-stage behavioral and medication treatments.

Another primary goal of our SMART pilot is to examine acceptability and feasibility of the SMART design and procedures. To this end, we are establishing and piloting our procedures for recruiting families from both adult and child providers. We are also piloting and assessing the acceptability of our study assessments, including distinguishing between masked study outcome assessments vs. treatment assessments that guide MSM titration or could be used to individualize interventions in practice, and triggers for initiating child medication. We have established procedures for implementing and refining sequential randomization procedures, including the optimal timing of notifying participants of their next phase of treatment that will provide a more seamless transition to the next phase. We developed a retention plan to obtain 6-month follow-up assessments via internet/telephone.

A final goal of our SMART pilot is to obtain preliminary data to support the planned full-scale SMART, including: obtaining recruitment and attrition rates; obtaining within-person correlations in primary and secondary outcomes; and conducting exploratory data analyses comparing longitudinal outcomes between families initially assigned to maternal stimulant medication vs. behavioral parent training.

In this paper we describe the rationale for, design of, and preliminary experiences with our ongoing pilot SMART (based on the first 26 participants). In further elaborating on the rationale for why a sequence of interventions is needed in this population and the clinical significance of the questions we seek to answer, this manuscript also illustrates the value of the SMART design for informing clinical decision making about how to combine, sequence, and personalize treatment for complex children and families.

Study Design

Participants

In our “Treating Mothers First” SMART Pilot study, we are recruiting 46 mothers with DSM-IV ADHD (any subtype), who have 3-8 year old children with elevated ADHD symptoms from providers who primarily see children or adults and from community advertisements (e.g., bus advertisements) in a large, metropolitan area. We will randomize 23 dyads to initial MSM and 23 to initial BPT. Accounting for attrition, we plan to observe at least 40 dyads through both stages of the SMART (i.e., at least 10 in each of the 4 treatment sequences), which we consider sufficient to examine our feasibility and acceptability aims (Almirall et al., 2012). Thus far, 26 families have been enrolled (see Table 1 for participant characteristics).

Table 1.

Demographic and Descriptive Characteristics of Mothers and Children.

| Maternal characteristics (n=26) | |

|---|---|

| Age | 39 years (M); 26—46 years (range) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 84.6% |

| African American | 3.8% |

| Multi-racial | 7.7% |

| Did not report | 3.8% |

| Ethnicity | |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 84.6% |

| Hispanic/Latino | 15.4% |

| Educational Level | |

| Graduated high school/high school equivalent | 7.7% |

| Partial college | 11.5% |

| Graduated 2-year college/technical school | 7.7% |

| Graduated 4-year college | 34.6% |

| Part graduate/professional school | 11.5% |

| Completed graduate/professional school | 26.9% |

| Marital Status | |

| Married | 73.1% |

| Divorced | 7.7% |

| Separated | 7.7% |

| Never Married | 11.5% |

| Income | |

| $0-$20,000 | 5.3% |

| $21,000-$40,000 | 10.5% |

| $41,000-$60,000 | 10.5% |

| $61,000-$80,000 | 10.5% |

| $81,000-$100,000 | 15.8% |

| $100,000+ | 26.3% |

| $200,000 | 0% |

| Did not disclose | 21.1% |

| ADHD subtype | |

| Inattentive | 57.7% |

| Hyperactive-Impulsive | 11.5% |

| Combined | 30.8% |

| Previous ADHD Medication Treatment | 23.1% |

| Current Comorbid Mood Disorder | 30.8% |

| Concurrent Antidepressant Treatment | 15.4% |

| Current Comorbid Anxiety Disorder | 19.2% |

| Concurrent Thyroid Problems | 19.2% |

| Lifetime History Comorbid Disorders | |

| Mood | 50.0% |

| PTSD | 15.4% |

| Other Anxiety | 23.1% |

| Substance Use | 7.7% |

| Adjustment Disorder | 3.8% |

| Eating Disorder | 3.8% |

|

Child Characteristics (n=26)

| |

| Gender | |

| Male | 58% |

| Female | 42% |

| Age | 6.2 years (M); 4—8 years (range) |

| ADHD | |

| Inattentive (n=7) | 26.9% |

| Hyperactive-Impulsive | 0 |

| Combined (n=14) | 53.8% |

| No ADHD Diagnosis (n=5) | 19.3% |

| Oppositional Defiant Disorder (n=8) | 30.7% |

For inclusion, mothers must: (1) Be between 21-50 years old and English-speaking; (2) Meet full DSM-IV criteria for ADHD, any subtype determined by clinical interview and ADHD Clinical Diagnostic Scale (ACDS); (3) Have current Clinical Global Impression-Severity (CGI-S)-ADHD rating of ≥ 4 (Moderately ill) and < 7 (Among the most extremely ill patients); (4) Have findings on physical exam, laboratory studies, vital signs, and electrocardiogram (ECG) judged to be normal for age with no contraindications for stimulant medication (e.g., hypertension, pregnancy, breastfeeding). Given high rates of comorbidity in adults with ADHD, mothers with common comorbid conditions (e.g., depression, anxiety) are included, as are participants who are medicated for these conditions on stable doses (i.e., not changed over the past 30 days) that are well-tolerated, with the approval of their prescriber.

For inclusion, children must: (1) be between ages 3 and 8 years; (2) have T scores >60, which is at least one standard deviation above the mean, on the Conners 3 Hyperactivity or Inattention scales, or on the Conners Early Childhood (EC) Inattention/Hyperactivity scale (3) have no prior treatment with stimulants, defined as one or more weeks of treatment with adequate doses or an adequate trial of BPT defined as more than 4 sessions; (4) for ethical reasons, not have severe ADHD at baseline that necessitates stimulant medication (based on clinical evaluation by the investigators). The child age range of 3-8 years was selected because early interventions may have a greater impact on the child's developmental trajectory and delay the need for medication. The need for child stimulant medication is assessed at each visit by the clinical team and is an outcome of interest.

Participants receive $50 for the 8 week, 16 week, and 6-month research assessments.

Procedures

Potential participants are first screened by telephone for basic inclusion/exclusion criteria. They are then invited to the hospital for a baseline assessment visit. At the baseline visit, potential participants receive an in-person explanation of the consent by the principal investigator or medical provider with the opportunity for the participant to ask questions. Then, a consent form and mother and child HIPAA Authorization forms are signed. If the child is seven or older, an assent form is also completed.

The SMART design is shown in Figure 1. All participants are randomized twice (at baseline and week 8), with “R” indicating when random assignment will be made. After the baseline assessment, mothers are randomized to either MSM or BPT for 8 weeks (Phase 1). At 8 weeks, all participants are evaluated and randomly assigned to the following treatment for weeks 9-16 (Phase 2): (1) continuation of initial treatment modality (with as-needed modifications), or (2) continuation of first-line treatment (modified as needed) with the addition of the treatment they did not receive previously. Thus, participants receive one of four treatment sequences (Figure 1). We are monitoring treatment effects at 8 and 16 weeks post-baseline and at 6-month follow-up on the following: (1) maternal ADHD symptoms and impairment; (2) parenting/family functioning; and (3) child ADHD symptoms. Child ADHD symptoms on the Conners Parent Hyperactivity Index and Conners Teacher Rating Scale are designated as primary outcomes.

Non-Restricted SMART Design

After much consideration, we decided to use a non-restricted SMART design for this pilot study, in which all participants are randomized to second-stage treatment regardless of response to first-line treatment. Ultimately, this decision was based on the inability to identify any clear ethical, feasibility, acceptability, cost-related, or scientific considerations suggesting that BPT+MSM or continued Phase 1 treatment ought to be offered to (or ruled-out for) some participants based on response to first-line treatment. Hence, in our SMART pilot we chose a design that would allow us to explore several different possible tailoring variables for the second-stage decision between continued first-stage treatment versus combined treatment.

Possible tailoring variables in our SMART may include parent ADHD symptoms or impairment, parenting quality, or child symptoms/impairment. We originally considered using the Barkley Family Impairment Scale (BFIS) to rule-out combined BPT+MSM for mothers with low impairment at the end of first-stage (re-randomizing only mothers with higher impairment to second-stage BPT+MSM versus continued). The BFIS is brief, easy to complete and score in real-world practice settings, has data-based clinical cutoff scores, and captures precisely what we are targeting—all necessary criteria for a primary tailoring variable. However, it was difficult to justify (for any clinical cutoff) that some participants with low BFIS should absolutely not be offered combined BPT+MSM: offering combined BPT+MSM in the second-stage is potentially feasible for all mothers with low impairment (despite first-stage BPT or MSM) and all mothers may stand to benefit from it. Further, it was difficult to justify using the BFIS over other measures (e.g., parenting scales and direct observation by Phase 1 therapist). In response, we decided to utilize a SMART design that (when implemented at full-scale) could be used to empirically inform the question of whether the BFIS (or other measures) could be used to individualize the clinical decision to continue on Phase 1 treatment versus combine MSM and BPT.

Treatments

We are using evidence-based treatments for ADHD as first-line/Phase 1 treatments, delivered as tested in numerous studies. Treatment takes place in a university children's hospital.

Maternal stimulant medication

The efficacy of pharmacotherapy in adults with ADHD has been well-established through randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses (e.g., Faraone & Glatt, 2010) and, at present, pharmacotherapy is the most widely-utilized treatment for adult ADHD. Lisdexamfetamine (LDX) is the longest-acting oral stimulant that has demonstrated efficacy in treating adult ADHD (Adler et al., 2013). LDX was chosen for treatment of maternal ADHD because of its frequent use in adults with ADHD and long duration of effect, with coverage in the late afternoon and early evening when numerous parenting challenges occur (e.g., dinner time, homework). Moreover, LDX was used in the only study that has demonstrated positive effects of stimulant medication on parenting outcomes (Waxmonsky et al., 2014).

The MSM protocol includes a 3-week open-label titration of LDX beginning at 20 mg using the Texas medication algorithm2. This dose is increased weekly during the titration period until an optimal response is obtained or the patient experiences poor tolerability. At each titration visit, the psychopharmacologist reviews the patient's Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scale (CAARS) and any patient reports of side effects, and then assigns a clinician Clinical Global Impression-Improvement (CGI-I) score. The goal is to identify the lowest tolerated dose of LDX that provides the greatest improvement in functioning. We expect this to be associated with a CGI-I ≤ 2 (Improved or Very Much Improved). Mimicking clinical practice, and guided by the Texas algorithm, in cases of poor tolerability or loss of efficacy, the medication type and/or dose can be switched to a long-acting methylphenidate, non-stimulant, or immediate-release (IR) stimulant. Participants return for monitoring during the course of MSM treatment on at least a monthly basis; they can be seen sooner in cases of poor tolerability or efficacy.

First-line BPT

We chose Barkley's Defiant Children, Third Edition (Barkley, 2013) as the BPT program due to its considerable empirical justification, clinical utility, and classification as an evidence-based treatment for children with ADHD (Evans et al., 2014). An individualized BPT format (as opposed to group BPT) allows us to initiate treatment immediately following assessment and allows more flexibility in scheduling. In this 8-week program, mothers are taught to identify and manipulate the antecedents and consequences of child behavior, target and monitor problematic behaviors, reward prosocial behavior, and decrease unwanted behavior through diversion of attention and non-physical discipline techniques. Session topics include: psychoeducation, special time, differential attention, effective commands, house rules, time-out, home point system, and home-school collaboration. Therapists consist of clinical psychology doctoral students, post-doctoral fellows, and licensed clinical psychologists who are trained and closely supervised by the first author to enhance reliability of BPT administration.

Second-line (Phase 2) Treatments

Continuation of MSM

Participants receiving sequence A (Figure 1) continue to receive MSM during the second 8 weeks. In cases of non-/partial-response to first-line MSM, the prescribing physicians and study team determine augmented pharmacotherapy algorithms. In cases of inadequate duration, LDX is supplemented with an IR stimulant. In cases of poor tolerability, long-acting or IR stimulants or non-stimulants (e.g., atomoxetine) are started (3-week titration, 5-week maintenance).

MSM + BPT

Dyads assigned to sequence B (Figure 1) receive MSM first for 8 weeks, and then standard BPT with continuation of the optimal dose of MSM for weeks 8-16 (as above).

Continuation of BPT

Participants assigned to sequence C (Figure 1) continue to receive weekly BPT during the second 8 weeks. If needed, based upon a functional analysis of the family and consultation from the first author, an individualized behavior plan is developed to enhance BPT efficacy. For example, strategies may be incorporated to address mothers’ time management and/or organizational difficulties if these problems interfere with consistent implementation of behavioral skills (Safren et al., 2010; Solanto et al., 2010). Evidence-based cognitive and behavioral strategies are also used to address additional problems that are not a focus of the first-line BPT, such as child anxiety, enuresis, or inconsistency between co-parents. Parent emotion coaching is also used for mothers who exhibit difficulty understanding or appropriately responding to their children's emotions (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2014).

BPT + MSM

Dyads assigned to sequence D (Figure 1) receive BPT first for 8 weeks (Phase 1), then MSM + BPT for weeks 9-16 (Phase 2). During Phase 2, monthly BPT sessions focus on maintenance and troubleshooting of skills taught during the phase 1.

Need for Child Medication

If, at any time, the child meets DSM-IV ADHD criteria and exceeds the severity threshold for moderately severe ADHD [determined by clinical interview and rating on the Clinical Global Impressions-Severity (CGI-S)>5], open-label child stimulant treatment is considered by the clinical team. In the SMART pilot study, we have developed and are testing the feasibility of protocols to initiate child medication and track this as an outcome.

Outcome Measures

Clinical assessments occur at baseline (BL), 8 weeks, 16 weeks, and at 6-month follow-up (Figure 1) by masked raters unaware of treatment sequence. Outcomes are assessed using multiple methods and informants across three domains: (1) maternal ADHD symptoms/functioning; (2) parenting/family functioning; (3) child ADHD symptoms, impairment, and need for stimulant treatment.

Child and maternal ADHD, rated by multiple informants, are measured as primary outcomes. The Conners has excellent reliability, specificity and sensitivity. The internal reliability coefficient for the Hyperactivity scale of the Conners is .91-.92 (Conners, Sitarenios, Parker, & Epstein, 1998). While parents are aware of which treatment arm they receive, we are also collecting Conners ratings from teachers, who are masked to treatment arm. The CAARS has demonstrated good internal consistency, acceptable inter-rater reliability, and importantly, sensitivity to treatment outcome (Adler et al., 2008). The CGI, commonly used in child and adult ADHD treatment research as an outcome measure indexing severity (Safren et al., 2010), is also being collected from masked evaluators. Lastly, we are collecting observed parenting and child behavior at each assessment that will be coded with a validated coding system by coders masked to treatment condition.

Treatment adherence

Adherence is measured for both MSM and BPT. Pill counts are used to estimate medication compliance, along with queries about reasons for missed doses at each study visit. The Treatment Adherence Inventory (slightly modified to mirror skills from the Barkley BPT manual) is administered to participants at the end of BPT and to therapists weekly to evaluate the extent to which the participant has used specific BPT skills consistently on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “almost never” to “almost always” (Kazdin, Holland, Crowley, & Breton, 1997). Attendance and continuous scores on this inventory are combined to measure BPT adherence (Nahum-Shani et al., 2012).

Treatment acceptability

After the week 16 outcome assessment, evaluators, therapists and psychopharmacologists are contacted by telephone by a research team member (with whom they have had no previous contact) and asked about their experience with study assessments, treatments, and study protocols/procedures. Participants also complete an anonymous acceptability and feasibility questionnaire at week 16. Based on feedback from parents and clinicians, we will refine study assessments, treatments and protocols for the full-scale SMART.

Preliminary Experiences

Conducting any clinical trial presents numerous challenges, and a pilot study is the ideal setting to recognize these challenges and learn how to address them. Given the complexity of sequencing treatments in this population, a pilot study is even more critical to the success of the larger-scale SMART (Almirall et al., 2012). While this SMART pilot study is on-going, here we describe some of the initial challenges we have encountered thus far with our first 26 participants. They include: (1) participant recruitment; (2) managing psychiatric comorbidity common among adults with ADHD; (3) determining the optimal psycho-pharmacological treatment algorithm; (4) considering patient preferences; and (5) conducting masked assessments.

Participant Recruitment

Although initially appealing and acceptable to parents and practitioners who see young at-risk youth, treating mothers and young children with ADHD has numerous challenges. This study was designed to be a prevention/early intervention study in that young children are not required to meet full diagnostic criteria for ADHD for inclusion. However, of the children entering the study thus far, 81% have already been diagnosed with ADHD (either previously or during the baseline assessment) and the mean age of children in the study is 6 years (range 4-8 years) (see Table 1). It has been a challenge to recruit younger children and children at-risk (i.e., with sub-clinical, rather than clinical, levels of ADHD). Willingness to commit to the study demands (i.e., lengthy assessments, weekly visits) and motivation to participate in the study may be greater when children's behaviors are more severe and impairing, perhaps as academic demands increase. Also, the fact the study is run in a children's hospital makes it more likely that parents will be presenting with more serious concerns related to their children.

We are attempting to recruit from both child and adult providers, as well as media sources. Not surprising, and like most clinical trials, of the 64 source-known referrals, many came from our own clinical practice (N = 23). Other sources of study referral include public relations and electronic media (N = 19), speaking at local advocacy group meetings (N = 6), study flyers (N = 8), friend referral (N = 2), bus advertisements (N = 2), and referrals from a primary care physician (N = 2), or another mental health provider (N=2). Although we are increasing efforts to familiarize adult providers with this study, to date, the majority of participants have come from child or pediatric sources (35%) and public relations/electronic media (29%). Such limited referral sources may limit generalizability of the pilot results.

Recruitment from adult sources has been slower than expected due to various reasons. Perhaps adult health practitioners, educators and even mental health providers are hesitant to refer parents to the study because the study is being conducted in a setting designed to see children. We have observed that providers that see adults may be less familiar with adult ADHD, may not identify ADHD as the presenting problem or may focus instead on an associated problem, such as mood symptoms. Specialty practices that focus on adult ADHD do see parents with ADHD; however, these parents are often already treated with ADHD medications, precluding their eligibility for this study. Participants recruited from adult providers may be different in some important way from families recruited from child practitioners, and their children may be less likely to have been diagnosed with ADHD. Thus, we are attempting to also recruit from family practice, internal medicine, and obstetrics/gynecology physician offices that see large volumes of women and/or that would be most likely to deliver the sequence of treatments examined in this study.

Thus far, mothers primarily contacted the study coordinators about the study, although in some cases, a study doctor informed a patient about the study and received permission to pass along the patient's information to the study coordinators, who subsequently contacted the interested family. Of the mothers (N = 94) who first contacted the study coordinators, 48 were not eligible primarily because the child was out of the age range for inclusion (typically older than 8 years; only one child was younger than 3 years), or because either the mother or child was already on effective doses of ADHD medication. To date, 32 participants have been consented for the study. Of those 32 consented participants, 26 were randomized to receive treatment. Five failed the initial screen assessing for inclusion and exclusion criteria (e.g., due to lack of impairment across settings, currently receiving medication) and one withdrew during screening due to the time commitment involved. Only one mother who was randomized withdrew at week 8, also due to the time commitment involved. As the study progresses, time commitment has been raised as a concern from several participants, even though the consenting process includes explaining that participants will need to commit to 16 weekly sessions plus two lengthy assessment sessions. It is possible that the tendency to over-commit, difficulty following through with plans, and organizational and future planning challenges that characterize adults with ADHD may interfere with participants’ ability to complete the study. We attempt to best accommodate participants’ needs and requests; for example, by offering the assessments over one to three sessions to accommodate their preferences, as well as offering weekend and after-hours appointments.

Additionally, our current sample is limited in its socio-demographic diversity (Table 1). The majority of mothers are Caucasian, married, and graduated from a 4-year college (or higher). Thus, it is unknown whether results would generalize to more demographically diverse populations. We are currently recruiting from bus advertisements and talks in the community to reach a broader demographic.

Managing Psychiatric Comorbidity Common Among Adults with ADHD

Although our sample to date is not very diverse in terms of race/ethnicity or education level, a clinical challenge in treatment development for mothers with ADHD is the wide range of severity and associated psychiatric comorbidity with which they present. The majority of mothers (61.5%) entered the study with a clinician-rated CGI severity level of “Markedly Ill.” This speaks to the need to individually tailor treatment intensity. As portrayed in Table 1, 57.7% of the mothers presented with ADHD inattentive subtype, 11.5% with hyperactive-impulsive subtype, and 30.8% with combined type. Also, there has been marked variability in participants’ comorbidity and medication treatment history (for example, 50% have a lifetime history of mood disorders and 15% are receiving antidepressants; Table 1).

In developing an effective treatment strategy, there is tension between providing treatment that is intensive enough to target cardinal ADHD symptoms and common impairments, while being feasible in terms of subject burden (in terms of the number of treatment sessions and overall length of the trial, particularly given participants’ concerns regarding the time commitment involved). We recognize that many parents present with emotion dysregulation, executive functioning deficits, and psychiatric comorbidities (including features of personality disorders) that may require additional or different forms of treatment, such as cognitive behavioral therapy or dialectical behavior therapy. However, as a first step, we elect to initially provide “off the shelf” evidence-based ADHD treatments that have demonstrated acute efficacy in 8 weeks or less. During Phase 2 of treatment, to the extent that these other difficulties are interfering with parenting and delivery of the behavioral parenting skills, they are addressed in treatment. However, therapists have often felt that the current length of treatment was insufficient for many of these families.

In addition, we are interested in monitoring the acceptability and pace of treatment. BPT progress appears to be slower for these families, as some parents need repetition of skills and more problem-solving to consistently implement the skills taught. Uptake of behavioral skills appears to be impacted by several factors, including joint custody arrangements, mothers’ trauma histories and comorbid mood disorders, and adult-ADHD related features (such as complete lack of household structure/routines, difficulty planning, distractibility that can lead to poor retention of presented skills, poor emotion regulation, and impatience). Preliminary baseline data using the Barkley Functional Impairment Scale indicate that mothers reported most difficulty functioning in their home life with immediate family (60%), in managing the household/completing chores (60%), and in organizing daily responsibilities (57%).

Additionally, several mothers randomized to receive BPT requested assistance regarding inconsistency with the co-parent. For mothers that were randomized to BPT for both phases of the trial, we amended the study protocol to allow for partners/co-parents to be involved in Phase 2. This allows for the opportunity to maximize consistency across parents/caregivers, especially when mothers expressed desire for assistance in teaching their partners BPT skills, and better mirrors real-world clinical practice. Our experiences thus far suggest that a BPT mastery model, such as Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT; McNeil & Hembree-Kigin, 2010), that involves hands-on coaching with the child in session (thus directly targeting ADHD-related performance deficits) might be a more useful way to intensify treatment in Phase 2, but this comes with added burdens (e.g., more specialized and extensive therapist training, lengthier treatment), which may limit uptake in real-world clinical settings. In future trials, PCIT may be an appropriate second-line treatment option for families that do not respond to first-line BPT.

One way we have amended our pilot study to better understand the skills participants use and which skills need additional focus includes administering the Treatment Adherence Inventory to caregivers (in addition to therapists) at the beginning of each session (this was previously collected only at the four major assessment points; Figure 1). This allows the BPT therapist to quickly glean which skills taught in the previous session may need more attention and which skills are reportedly being used. Adherence data will also be included as a key study outcome, as we hypothesize that mothers may more consistently utilize behavioral parenting skills when they are first medicated for their adult ADHD (MSM+BPT; sequence B).

Determining the Optimal Psychopharmacological Treatment Algorithm

Similar challenges are faced in designing the pharmacological treatment algorithm for mothers with ADHD. Although stimulant medications are widely used to treat ADHD in a variety of age ranges, much less is known about optimal treatment for adults with ADHD. Even though adults may require a longer duration than provided by the longest-acting stimulants (especially considering parenting demands such as the bedtime routine), it is paradoxical that IR stimulants are commonly prescribed for adults. The Texas Algorithm used in our study (Hughes et al., 2007) allows for mothers deriving inadequate duration from LDX to receive a second IR dose to achieve longer coverage. As of yet, we have had few participants who elected to receive a second IR dose after a long-acting preparation. Further investigation is needed to examine the determinants or predictors of medication regimen preference and response.

Considering Patient Preferences

Based on our experience with the first 26 participants, we are interested in examining the role of initial patient preference for BPT or medication and whether treatment preference is associated with the acceptability of assigned study treatment and response. Study treatments differ markedly in their availability, cost, burden, and preference. Since we do not know if patient preference makes a difference in adherence or outcome, by randomly assigning participants to treatment and surveying preference, we will be able to examine this potential moderator. To date, participants have been willing to receive either treatment (MSM or BPT) despite some participants informally communicating to research staff that they did not receive their preferred treatment. In particular, mothers not assigned to receive BPT (MSM+MSM) have expressed disappointment to study staff. Still, no participants have dropped out as a result of being randomized to a less-preferred treatment. It is unknown, however, if some patients initially declined to enroll because of the potential to be randomized to a less preferred treatment modality.

In addition to initial patient preference, we encountered one participant whose child's symptoms worsened during the course of the study, and the mother expressed wanting BPT skills despite being assigned to MSM+MSM. The study was designed only to include a child medication rescue clause, meaning that children who were severely impaired could be prescribed medication. However, this experience created discussion that our future studies should include both medication and BPT rescue clauses for cases in which families were not randomized to BPT, but either need or request parenting support.

Conducting Masked Assessments

Finally, we have spent considerable time related to issues around keeping clinicians conducting research assessments (independent evaluators) masked to treatment randomization.

Clinicians who conduct 8 week, 16 week, and 6-month follow up research assessments (including the CGI) are not privy to conversations that would reveal treatment assignment (e.g., BPT supervision). The assessment clinician reminds the mother not to share this information before the outcome assessment begins; however, the participant sometimes reveals their treatment status to the masked clinician (perhaps due to impulsivity). Also, the BPT therapist does not receive clinical information about a new participant directly from the screening clinician as this would un-mask the screening clinician (who may also conduct future masked outcome assessments). Additionally, both parents and teachers complete the Conners (our primary child outcome); because teachers are not aware of treatment assignment, they are able to provide masked reports of child ADHD symptoms. Finally, we collect observational measures of parenting and child behavior which are coded by observers who are unaware of treatment condition.

Conclusions

In this report, we describe the rationale and design of an ongoing SMART pilot to target treatment for both parents and children in high-risk families, and share our preliminary experiences in conducting this ongoing trial. Prior research suggests that parent ADHD impacts the quality of parenting, which has implications for the developmental outcomes of their children. Moreover, evidence, though mixed, suggests that parents with ADHD may not derive full clinical benefit from evidence-based behavioral interventions for their children (Wang et al., 2014). Finally, attempts to medicate parents with ADHD to improve parenting and child outcomes have yielded mixed results (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2010; Waxmonsky et al., 2014), suggesting that a combined pharmacological-behavioral approach is likely needed for many of these families. Determination of the optimal treatment approach, sequencing of these treatments, and moderators of response are important questions faced by clinicians working with these families. Given the novelty of the concept and the complexity of families with ADHD, there is much to be learned about accessing and intervening with families of young children with ADHD symptoms in which a parent has ADHD. This pilot SMART is designed to answer questions about acceptability of interventions, measures, and aspects of the study design and protocols prior to implementing a fully-powered SMART. Ultimately, we seek to answer for whom more intensive, multimodal treatments is needed, in what sequence these treatments should be delivered, and what baseline and early response characteristics can inform these important clinical decisions. Elucidating the answers to such questions has important implications for clinicians providing care to these complex families.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This study was sponsored by NIH-R34MH0099208, Sequencing Treatment for Mothers with ADHD and Their at-Risk Children (A. Chronis-Tuscano and M. Stein, PI's), with study drug and additional support provided by Shire Pharmaceuticals to Dr. Stein.

Footnotes

In the majority of cases the children were already treated with stimulants reducing opportunities to demonstrate change (Stein, in press).

The Texas Algorithm was initially developed to provide a formula to prescribe medication to treat child mental health disorders. The algorithm regarding ADHD treatment recommends that if a patient is a non-responder, or develops intolerable side effects on one stimulant formulation (i.e., methylphenidate or amphetamine), that they have a trial with the alternative stimulant class.

References

- Adler LA, Faraone SV, Spencer TJ, Michelson D, Reimherr FW, Glatt SJ, Biederman J. The reliability and validity of self and investigator ratings of ADHD in adults. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2008;11(6):711–719. doi: 10.1177/1087054707308503. doi: 10.1177/1087054707308503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler LA, Lynch LR, Shaw DM, Wallace SP, O'Donnell KE, Ciranni MA, Faraone SV. Effectiveness and duration of effect of open-label lisdexamfetamine dimesylate in adults with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders. Advance Online Publication. 2013 doi: 10.1177/1087054713485421. doi: 10.1177/1087054713485421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almirall D, Compton SN, Gunlicks-Stoessel M, Duan N, Murphy SA. Designing a pilot sequential multiple assignment randomized trial for developing an adaptive treatment strategy. Statistics in Medicine. 2012;31(17):1887–1902. doi: 10.1002/sim.4512. doi: 10.1002/sim.4512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA. Defiant children: A clinician's manual for assessment and parent training. 3rd ed. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Faraone SV, Monuteaux MC. Impact of exposure to parental attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder on clinical features and dysfunction in the offspring. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32(5):817–827. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702005652. doi: 10.1017/S0033291702005652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charach A, Carson P, Fox S, Ali MU, Beckett J, Lim CG. Interventions for preschool children at high risk for ADHD: A comparative effectiveness review. Pediatrics. 2013;131:1–21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0974. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-0974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronis AM, Lahey BB, Pelham WE, Jr., Williams SH, Baumann BL, Kipp H, Rathouz PJ. Maternal depression and early positive parenting predict future conduct problems in young children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43(1):70–82. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.1.70. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Lewis-Morrarty E, Woods KE, O'Brien KA, Mazursky-Horowitz H, Thomas SR. Parent–Child Interaction Therapy With Emotion Coaching for Preschoolers With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2014 Advanced Online Publication. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.11.001. [Google Scholar]

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Rooney M, Seymour KE, Lavin HJ, Pian J, Robb A, Stein MA. Effects of maternal stimulant medication on observed parenting in mother-child dyads with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39(4):581–587. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2010.486326. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2010.486326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Seymour KE, Stein MA, Jones HA, Jiles CD, Rooney ME, Robb AS. Efficacy of osmotic-release oral system (OROS) methylphenidate for mothers with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): Preliminary report of effects on ADHD symptoms and parenting. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69(12):1938–1947. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n1213. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v69n1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Stein MA. Pharmacotherapy for parents with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): Impact on maternal ADHD and parenting. CNS Drugs. 2012;26(9):725–732. doi: 10.2165/11633910-000000000-00000. doi: 10.2165/11633910-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK, Sitarenios G, Parker JD, Epstein JN. The revised Conners' Parent Rating Scale (CPRS-R): Factor structure, reliability, and criterion validity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1998;26(4):257–268. doi: 10.1023/a:1022602400621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SW, Owens JS, Bunford N. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2014;43(4):527–551. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.850700. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.850700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraone SV, Glatt SJ. A comparison of the efficacy of medications for adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder using meta-analysis of effect sizes. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2010;71(6):754–63. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04902pur. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04902pur. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraone SV, Perlis RH, Doyle AE, Smoller JW, Goralnick JJ, Holmgren MA, Sklar P. Molecular Genetics of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57(11):1313–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.024. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhill L, Kollins S, Abikoff H, McCracken J, Riddle M, Swanson J, Cooper T. Efficacy and Safety of Immediate-Release Methylphenidate Treatment for Preschoolers With ADHD. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45(11):1284–1293. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000235077.32661.61. doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000235077.32661.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harold GT, Leve LD, Barrett D, Elam K, Neiderhiser JM, Natsuaki MN, Thapar A. Biological and rearing mother influences on child ADHD symptoms: Revisiting the developmental interface between nature and nurture. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2013;54(10):1038–1046. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12100. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey EA, Metcalfe LA, Herbert SD, Fanton JH. The role of family experiences and ADHD in the early development of oppositional defiant disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79(6):784–795. doi: 10.1037/a0025672. doi: 10.1037/a0025672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healey DM, Gopin CB, Grossman BR, Campbell SB, Halperin JM. Mother-child dyadic synchrony is associated with better functioning in hyperactive inattentive preschool children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;51(9):1058–1066. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02220.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes CW, Emslie GJ, Crismon ML, Posner K, Birmaher B, Ryan N, Lopez M. Texas children's medication algorithm project: update from Texas consensus conference panel on medication treatment of childhood major depressive disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46(6):667–686. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31804a859b. doi:10.1097/chi.0b013e31804a859b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jans T, Jacob C, Warnke A, Zwanzger U, Groß-Lesch S, Matthies S, Philipsen A. Does intensive multimodal treatment for maternal ADHD improve the efficacy of parent training for children with ADHD? A randomized controlled multicenter trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12443. Advanced online publication doi:10.1111/jcpp.12443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston C, Mash EJ, Miller N, Ninowski JE. Parenting in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Clinical Psychology Review. 2012;32(4):215–228. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.01.007. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Holland L, Crowley M, Breton S. Barriers to Treatment Participation Scale: Evaluation and validation in the context of child outpatient treatment. Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines. 1997;38(8):1051–1062. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01621.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil CB, Hembree-Kigin TL. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy. 2nd Ed. Springer Science & Business Media; New York, NY: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Molina BSG, Pelham WE, Jr., Cheong J, Marshal MP, Gnagy EM, Curran PJ. Childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and growth in adolescent alcohol use: The roles of functional impairments, ADHD symptom persistence, and parental knowledge. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121(4):922–935. doi: 10.1037/a0028260. doi: 10.1037/a0028260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahum-Shani I, Qian M, Almirall D, Pelham WE, Gnagy B, Fabiano GA, Murphy SA. Experimental design and primary data analysis methods for comparing adaptive interventions. Psychological Methods. 2012;17(4):457. doi: 10.1037/a0029372. doi: 10.1037/a0029372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Sprich S, Mimiaga MJ, Surman C, Knouse L, Groves M, Otto MW. Cognitive behavioral therapy vs relaxation with educational support for medication-treated adults with ADHD and persistent symptoms: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;304(8):875–880. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1192. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solanto MV, Marks DJ, Wasserstein J, Mitchell K, Abikoff H, Alvir JMJ, Kofman MD. Efficacy of meta-cognitive therapy for adult ADHD. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167(8):958–968. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09081123. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09081123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MA, et al. Commentary: Does helping mothers with ADHD in multiplex families help children? Reflections on Jans. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12454. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CH, Mazursky-Horowitz H, Chronis-Tuscano A. Delivering Evidence-Based Treatments for Child Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in the Context of Parental ADHD. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2014;16(10):1–8. doi: 10.1007/s11920-014-0474-8. doi: 10.1007/s11920-014-0474-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waschbusch DA, Cunningham CE, Pelham WE, Jr., Rimas HL, Greiner AR, Gnagy EM, Hoffman MT. A discrete choice conjoint experiment to evaluate parent preferences for treatment of young, medication naive children with ADHD. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2011;40(4):546–561. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.581617. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.581617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waxmonsky JG, Waschbusch DA, Babinski DE, Humphrey HH, Alfonso A, Crum KI, Pelham WE. Does Pharmacological Treatment of ADHD in Adults Enhance Parenting Performance? Results of a Double Blind Randomized Trial. CNS Drugs. 2014;28(7):665–77. doi: 10.1007/s40263-014-0165-3. doi: 10.1007/s40263-014-0165-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolraich ML, Bard DE, Stein MT, Rushton JL, O'Connor KG. Pediatricians’ attitudes and practices on ADHD before and after the development of ADHD pediatric practice guidelines. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2010;13(6):563–572. doi: 10.1177/1087054709344194. doi:10.1177/1087054709344194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]