Abstract

Over the last decade, mutation studies have grown in popularity due to the affordability and accessibility of whole-genome sequencing. As the number of species in which spontaneous mutation has been directly estimated approaches 20 across two domains of life, questions arise over the repeatability of results in such experiments. Five species were identified in which duplicate mutation studies have been performed. Across these studies the difference in estimated spontaneous mutation rate is at most, weakly significant (p < 0.01). However, a highly significant (p < 10−5), three-fold difference in the rate of insertions / deletions (indels) exists between two recent studies in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Upon investigation of the ancestral genome sequence for both studies, a possible anti-mutator allele was identified. The observed variation in indel rate may imply that the use of indel markers, such as microsatellites, for the investigation of genetic diversity within and among populations may be inappropriate because of the assumption of uniform mutation rate within a species.

Keywords: Schizosaccharomyces pombe, mutation accumulation, indel, yeast, evolution, DNA repair, microsatellite

Mutation is the ultimate source of all genetic variation, and has been a long-standing research focus in evolutionary genetics. Until recently, estimating mutation rates has necessitated using reporter loci [1] and it has not been possible to obtain direct estimates of the mutation spectrum, which is the relatively frequency of different nucleotide substitutions, insertions / deletions (indels), and rearrangements. However, with current methods, sequencing massive amounts of DNA to discover the relatively few newly-arising, spontaneous mutations at the genome level is now affordable. This has allowed mutation-accumulation (MA) studies [2] to be used to estimate both the genome-wide mutation rate and its spectrum in a variety of organisms: Arabidopsis thaliana [3, 4], Bacillus subtilis [5], Burkholderia cenocepacia [6], Caenorhabditis elegans [7, 8], Chlamydomonas reinhardtii [9, 10], Daphnia pulex [11], Dictyostelium dicsoideum [12], Dienococcus radiodurans [13], Drosophila melanogaster [14, 15],Escherichia coli [16], Heliconius melpomene [17], Mesoplasma florum [10], Paramecium tetraurelia [18], Pristionchus pacificus [19], Pseudomonas aeruginosa [20], Pseudomonas fluorescens [21], Saccharomyces cerevisiae [22-24], Schizosaccromyces pombe [25, 26], andTetrahymena thermophila [27]. As the list of species for which genome-wide estimates or mutation rate and spectrum are available increases, the question of repeatability becomes paramount.

Genome-wide estimates of parameters of mutation have been performed in the same species only a few times, either as controls for an experimental evolution project or as a specific effort to understand the spontaneous mutation rate, so the reproducibility of results has seldom been examined. The five species with two independent genome-wide estimates reported before 2015 are included in Table 1, which indicates that they often suffer from low power due to small sample size, making it difficult to evaluate reproducibility.

Table 1.

Comparison of repeated, genome-wide estimates of single nucleotide (μSNM) and small (≤ 50bp) insertion/deletion (μindel) mutation rates across species obtained from mutation accumulation (MA) experiments. Differences between the two estimates within a species are tested for significance using a Welch's t-test, with appropriate degrees of freedom. To calculate the standard error for the t-test, the variance among lines in the number of mutations is assumed to be equal to the mean number of mutations per line, which assumes that mutation is a Poisson process. The fold difference (diff) between estimates within a species is shown (= larger/smaller estimate). The number of MA lines (N) and generations of accumulation (Gens), and the number of observed mutation events used for parameter estimation (SNMs and Indels) are shown. N = number of mutation accumulation lines in the study, Gens = generations, SNM = single nucleotide mutation, indel = insertion/deletion of less than 50bp, CI = confidence interval, NS = not significant.

| Species | Studya | N | Gens | SNMs | Indels | μSNM (CIb) (× 10−9) | μSNM diff | μindel (CIb) (× 10−9) | μindel diff |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana | 1 | 5 | 30 | 98 | 13 | 4.84 (3.86-5.82) | 1.34 | 0.64 (0.28-1.00) | 1.10 |

| 2 | 9 | 10 | 44 | 7 | 3.62 (2.53-4.71) | NS | 0.58 (0.14-1.01) | NS | |

| Chlamydomonas reinhardtii | 3 | 2 | 350 | 9 | 5 | 0.21 (0.07-0.35) | 3.5 | 0.12 (0.01-0.22) | 3.00 |

| 4 | 4 | 1730 | 20 | 13 | 0.06 (0.03-0.09) | NS | 0.04 (0.01-0.06) | NS | |

| Drosophila melanogaster | 5 | 8 | 147 | 732 | 60 | 5.49 (5.08-5.90) | 1.96 | 0.45 (0.33-0.57) | 2.67 |

| 6 | 12 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 2.80 (0.51-5.09) | P<0.05 | 1.20 (0.00-3.02) | NS | |

| Caenorhabditis elegans | 7 | 7 | 250 | 108 | - | 1.33 (1.07-1.59) | 2.53 | - | - |

| 8 | 6 | 20 | 60 | 7 | 3.37 (2.50-4.24) | P<0.01 | 0.58 (0.100.69) | ||

| Schizosaccharo myces pombe | 9 | 96 | 1716 | 398 | 117 | 0.20 (0.18-0.22) | 1.18 | 0.06 (0.05-0.07) | 2.83 |

| 10 | 79 | 1952 | 327 | 335 | 0.17 (0.15-0.19) | P<0.05 | 0.17 (0.16-0.19) | P<10−5 | |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae c | 11 | 2 | 1000 | 14 | 0 | 0.29 (0.14-0.45) | 1.71 | - | - |

| 12 | 140 | 2062 | 867 | 26 | 0.17 (0.16-0.18) | NS | 0.005 (0.00-0.01) |

1 = Ossowski et al. 2010, 2 = Jiang et al. 2014, 3 =Ness et al. 2012, 4 = Sung et al. 2012, 5 = Schrider et al. 2012, 6 = Keightley et al. 2014, 7 = Denver et al. 2012, 8 = Meier et al. 2014, 9 = Farlow et al. 2015, 10 = Behringer and Hall 2016, 11 = Nishant et al. 2010, 12 = Zhu et al. 2014.

Confidence intervals are from standard errors of the number of mutations per line, which are estimated by assuming a Poisson distribution of mutations across lines.

Diploid strains

Our recent mutation accumulation study in Schizosaccharomyces pombe [26] unintentionally overlapped a concurrent study of similar scope [25] and allowed a statistically robust comparison of the repeatability of mutation rate and spectrum estimates in this species. The conditions of the two experiments differed with respect to starting strain, culture temperature, time between line transfers and growth medium, but were otherwise similar.

Genome-wide mutation rates vary across studies. In the five species with data prior to 2015, the single nucleotide mutation rate estimates vary 1.34 to 3.50 fold (Table 1). In comparison, the single nucleotide mutation rate estimates in the two S. pombe studies are only 1.18 fold different. This difference, though smaller than seen in the other five species, is statistically significant (P < 0.05). In previous studies, the mutation rate for small (≤ 50bp) indels varied from 1.10 to 3.00 fold, though none of the differences were significant because of the low number of observed mutational events (Table 1). In comparison, the indel mutation rate estimates in the two S. pombe studies are 2.83 fold different, which is a highly statistically significant difference (P < 10−5).

There are at least three possible explanations for the ~3 fold difference observed in indel rates in S. pombe. First, indels are more challenging to accurately detect bioinformatically than base substitutions, not only because the resulting mismatches can make an indel-containing sequencing read more difficult to map, but also because indels commonly occur within microsatellites and highly repetitive regions which already have an increased PCR and sequencing error rate [28, 29]. Two different pipelines were used for small indel detection in the two studies. In Farlow et al., sequencing reads were mapped with BWA [30], and realigned with both Breakdancer [31] and Pindel [32]. In our study, we also mapped sequencing reads with BWA, but realigned them with GATK's IndelRealigner [33]. Both practices are not without their issues; GATK is less sensitive when it comes to larger indels, while Pindel has trouble with insertions [29]. In our study, we estimated the false positive and false negative error rates and found them both to be less than 2.5%. Even if error rates were an order of magnitude greater in the Farlow et al. study, they would be insufficient to explain the difference in indel mutation rate.

Second, the indel mutation rate may be altered by the different environmental conditions of the two experiment, with temperature being a likely candidate [34]. Stressful temperatures have been demonstrated to affect microsatellite mutation rate in Caenorhabditis elegans [34], with increased temperatures leading to an increase in mutation rate. However, if S. pombe also exhibits increased indel mutation rate at stressful temperatures, we would expect the Farlow et al. study to have a higher rate, since they performed their mutation accumulation experiment at a higher, presumably more stressful, temperature (32° vs 30°C). There is no obvious other difference that would suggest that S. pombe was more or less stressed in one versus the other experiment.

Third, differences in genetic background may explain the different indel mutation rates. To examine this hypothesis, we compared the ancestral strains in the two studies, specifically to ask whether ours exhibited a higher relative number of indels when compared to the reference. In our MA study, we found 315 indel and single nucleotide substitution differences between the ancestor and reference genome, which was a surprisingly large number given that both isolates have the same strain designation (972 h-). A comparison of our ancestor with the one used by Farlow et al., identified 208 shared differences. This high number of shared differences between the ancestors strongly suggests that they represent errors in the reference assembly. The reference genome is thought to have at least 190 errors [35, 36], 183 of which are among the 208 shared mutations, and thus confirmed by our analysis. The remaining 25 have not been previously inferred (Supplemental Table). Of the remaining 107 differences between our ancestor and the reference, there are approximately 3.5 fold more indels than single nucleotide mutations. A similar analysis of Farlow et al.'s ancestor indicates 0.95 fold more indels than single nucleotide mutations, relative to the reference. Thus, our ancestor shows a 3.7 fold higher number of indels, relative to single nucleotide changes, compared to the Farlow et al. ancestor. This suggests that there may indeed be a genetic background difference between the two strains that is causing a relatively higher indel mutation rate in our ancestral strain. We note that there is no evidence for selection having played a major role in the mutational differences between either ancestor: the effects of mutational differences between the ancestors and the reference are not significantly different from those that arose during MA, when selection is known to be ineffective (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Comparison of mutational effects in MA ancestor and MA lines. There is no difference between any of the three spectra (Chi-squared test: p-value = 0.61).

When examining differences between the ancestors for their potential to cause differences in indel rate, two mutations were found in genes associated with DNA repair in the Farlow et al. ancestor. One of these is in rev7 (SPBC12D12.09), which is a subunit of DNA polymerase zeta with inferred involvement in translesion synthesis [37], but the mutation is synonymous and thus not likely to have an effect, unless it alters mRNA stability and thus protein levels in the cell. The second is a missense mutation in cdc6 (SPBC336.04), also known as POLD3, which is a subunit of DNA polymerase delta. A mutation in cdc6, specifically cdc6-121 has known mutator qualities, while another variant, cdc6-23, may reduce the mutation rate relative to wild-type [38]. It's possible that the cdc6 missense mutation in the Farlow ancestor has anti-mutator qualities, which could account for the indel differences between the two ancestors and the estimated rate differences in the two MA experiments.

Regardless of whether it is environmental or due to genetic background, the substantial variation seen in indel rate has serious implications for the use of microsatellite repeats as genetic markers. In nature, populations that appear to be significantly different in their microsatellite genotypes and are thus inferred to be genetically isolated from others may simply have higher mutation rates. Microsatellite mutation models, such as the stepwise-mutation model [39], assume uniformity in the indel rate within species. While warnings have been issued about the robustness of microsatellites due to differing mutation rates amongst loci [40], microsatellites may also miscalculate genetic distance because of differing mutation rates amongst populations.

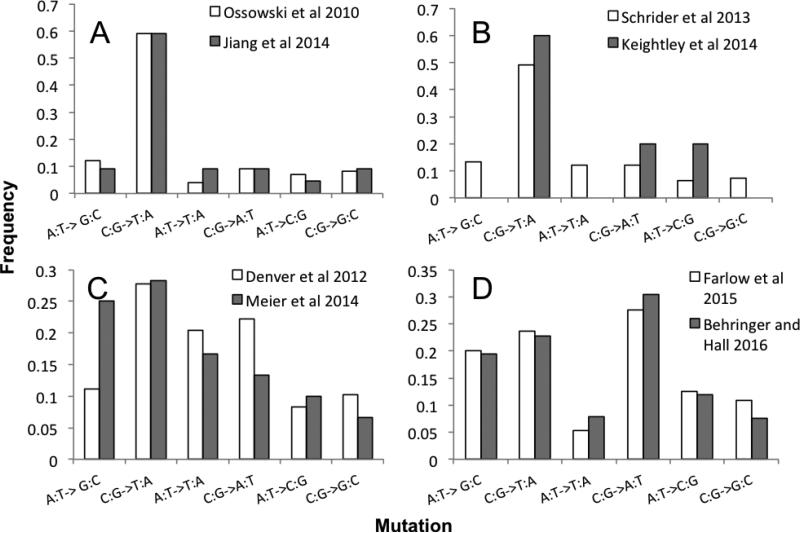

Other parameters of the mutational process, which require large numbers of mutations to estimate with precision, including the spectrum of single nucleotide mutations, the insertion to deletion ratio for small indels, and the location of mutational hotspots do not differ between the two studies. Three of the previous studies have sufficient numbers of single nucleotide mutations to estimate the spectrum for this class of mutations (Figure 2). In these three species, and in S. pombe, the spectra are remarkably similar to one another. The relative frequency of insertions versus deletions in small indels across studies within species can only be compared within S. pombe; there are insufficient numbers of indels in other studies. The ratio of insertions to deletions is not significantly different in the two MA studies; it is 5.88 in Farlow et al. and 6.12 in our study. Further, the ratio of insertions to deletions is similar, 6.4, for those indels that differ between our ancestor and the reference, after removing those that are shared with the Farlow et al. ancestor. It is only in the Farlow ancestor, in which the ratio is 0.82, based on 20 indels, that we find a significant difference (Fisher's Exact Test, P ≤ 0.0003) from the others we have observed.

Figure 2.

Comparison of mutation accumulation spectra for the four species in which there are sufficient numbers of mutations to make a comparison. In all four species, spectra are not significantly different across studies (Chi-squared test: A: A. thaliana, p-value = 0.75, B: D. melanogaster, p-value = 0.58, C: C. elegans, p-value = 0.164, D: S. pombe, p-value = 0.66) .

In conclusion, the inadvertent overlap of our S. pombe MA experiment with that of Farlow et al. allowed one of the first statistically robust comparisons of estimates of parameters of mutation within a species. Generally, estimates revealed remarkable repeatability. The single nucleotide mutation rates, though statistically significantly different, were within 20% of one another, and the mutational spectrum for these mutations was not different. Further the relative occurrence of insertions to deletion was also not different across the two studies. The only substantial difference was the indel mutation rate, which varies by ~3 fold across the two studies and is highly statistically significant. This suggests that the mutation rate for indels may be more sensitive to genetic background, environment, or both.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Drake JW. A constant rate of spontaneous mutation in DNA-based microbes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1991;88:7160–7164. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lynch M, Blanchard J, Houle D, Kibota T, Schultz S, Vassilieva L, Willis J. Perspective: spontaneous deleterious mutation. Evolution. 1999:645–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1999.tb05361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ossowski S, Schneeberger K, Lucas-Lledó JI, Warthmann N, Clark RM, Shaw RG, Weigel D, Lynch M. The rate and molecular spectrum of spontaneous mutations in Arabidopsis thaliana. science. 2010;327:92–94. doi: 10.1126/science.1180677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang C, Mithani A, Belfield EJ, Mott R, Hurst LD, Harberd NP. Environmentally responsive genome-wide accumulation of de novo Arabidopsis thaliana mutations and epimutations. Genome research. 2014;24:1821–1829. doi: 10.1101/gr.177659.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sung W, Ackerman MS, Gout J-F, Miller SF, Williams E, Foster PL, Lynch M. Asymmetric Context-Dependent Mutation Patterns Revealed through Mutation–Accumulation Experiments. Molecular biology and evolution. 2015:msv055. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msv055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dillon MM, Sung W, Lynch M, Cooper VS. The rate and molecular spectrum of spontaneous mutations in the GC-rich multi-chromosome genome of Burkholderia cenocepacia. Genetics, genetics. 2015;115:176834. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.176834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Denver DR, Dolan PC, Wilhelm LJ, Sung W, Lucas-Lledó JI, Howe DK, Lewis SC, Okamoto K, Thomas WK, Lynch M. A genome-wide view of Caenorhabditis elegans base-substitution mutation processes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106:16310–16314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904895106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meier B, Cooke SL, Weiss J, Bailly AP, Alexandrov LB, Marshall J, Raine K, Maddison M, Anderson E, Stratton MR. C. elegans whole-genome sequencing reveals mutational signatures related to carcinogens and DNA repair deficiency. Genome research. 2014;24:1624–1636. doi: 10.1101/gr.175547.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ness RW, Morgan AD, Colegrave N, Keightley PD. Estimate of the spontaneous mutation rate in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Genetics. 2012;192:1447–1454. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.145078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sung W, Ackerman MS, Miller SF, Doak TG, Lynch M. Drift-barrier hypothesis and mutation-rate evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109:18488–18492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216223109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keith N, Tucker AE, Jackson CE, Sung W, Lledó JIL, Schrider DR, Schaack S, Dudycha JL, Ackerman MS, Younge AJ. High mutational rates of large-scale duplication and deletion in Daphnia pulex. Genome Research, gr. 2015:191338191115. doi: 10.1101/gr.191338.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saxer G, Havlak P, Fox SA, Quance MA, Gupta S, Fofanov Y, Strassmann JE, Queller DC. Whole genome sequencing of mutation accumulation lines reveals a low mutation rate in the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum. 2012 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Long H, Kucukyildirim S, Sung W, Williams E, Lee H, Ackerman M, Doak TG, Tang H, Lynch M. Background mutational features of the radiation-resistant bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans. Molecular biology and evolution. 2015:msv119. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msv119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schrider DR, Houle D, Lynch M, Hahn MW. Rates and genomic consequences of spontaneous mutational events in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2013;194:937–954. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.151670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keightley PD, Ness RW, Halligan DL, Haddrill PR. Estimation of the spontaneous mutation rate per nucleotide site in a Drosophila melanogaster full-sib family. Genetics. 2014;196:313–320. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.158758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee H, Popodi E, Tang H, Foster PL. Rate and molecular spectrum of spontaneous mutations in the bacterium Escherichia coli as determined by whole-genome sequencing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109:E2774–E2783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210309109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keightley PD, Pinharanda A, Ness RW, Simpson F, Dasmahapatra KK, Mallet J, Davey JW, Jiggins CD. Estimation of the spontaneous mutation rate in Heliconius melpomene. Molecular biology and evolution. 2014:msu302. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sung W, Tucker AE, Doak TG, Choi E, Thomas WK, Lynch M. Extraordinary genome stability in the ciliate Paramecium tetraurelia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109:19339–19344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210663109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weller AM, Rödelsperger C, Eberhardt G, Molnar RI, Sommer RJ. Opposing forces of A/T-biased mutations and G/C-biased gene conversions shape the genome of the nematode Pristionchus pacificus. Genetics. 2014;196:1145–1152. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.159863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dettman JR, Sztepanacz JL, Kassen R. The properties of spontaneous mutations in the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa. BMC Genomics. 2016;17:1. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-2244-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Long H, Sung W, Miller SF, Ackerman MS, Doak TG, Lynch M. Mutation Rate, Spectrum, Topology, and Context-Dependency in the DNA Mismatch Repair-Deficient Pseudomonas fluorescens ATCC948. Genome biology and evolution. 2015;7:262–271. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evu284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lynch M, Sung W, Morris K, Coffey N, Landry CR, Dopman EB, Dickinson WJ, Okamoto K, Kulkarni S, Hartl DL. A genome-wide view of the spectrum of spontaneous mutations in yeast. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105:9272–9277. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803466105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishant K, Wei W, Mancera E, Argueso JL, Schlattl A, Delhomme N, Ma X, Bustamante CD, Korbel JO, Gu Z. The baker's yeast diploid genome is remarkably stable in vegetative growth and meiosis. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001109. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu YO, Siegal ML, Hall DW, Petrov DA. Precise estimates of mutation rate and spectrum in yeast. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2014;111:E2310–E2318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323011111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farlow A, Long H, Arnoux S, Sung W, Doak TG, Nordborg M, Lynch M. The spontaneous mutation rate in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics. 2015;201:737–744. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.177329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Behringer MG, Hall DW. Genome wide estimates of mutation rates and spectrum in Schizosaccharomyces pombe indicate CpG sites are highly mutagenic despite the absence of DNA methylation. G3: Genes| Genomes| Genetics, g3. 2015:115.022129. doi: 10.1534/g3.115.022129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Long H, Winter DJ, Chang AY-C, Sun W, Whu SH, Balboa M, Azevedo RB, Cartwright RA, Lynch M, Zufall RA. Low base-substitution mutation rate in the ciliate Tetrahymena thermophila. bioRxiv. 2015 doi: 10.1093/gbe/evw223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang Y, Turinsky AL, Brudno M. The missing indels: an estimate of indel variation in a human genome and analysis of factors that impede detection. Nucleic acids research. 2015:gkv677. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Narzisi G, O'Rawe JA, Iossifov I, Fang H, Lee Y.-h., Wang Z, Wu Y, Lyon GJ, Wigler M, Schatz MC. Accurate de novo and transmitted indel detection in exome-capture data using microassembly. Nature methods. 2014;11:1033–1036. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows– Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen K, Wallis JW, McLellan MD, Larson DE, Kalicki JM, Pohl CS, McGrath SD, Wendl MC, Zhang Q, Locke DP. BreakDancer: an algorithm for high-resolution mapping of genomic structural variation. Nature methods. 2009;6:677–681. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ye K, Schulz MH, Long Q, Apweiler R, Ning Z. Pindel: a pattern growth approach to detect break points of large deletions and medium sized insertions from paired-end short reads. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2865–2871. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Auwera GA, Carneiro MO, Hartl C, Poplin R, del Angel G, Levy - Moonshine A, Jordan T, Shakir K, Roazen D, Thibault J. From FastQ data to high - confidence variant calls: the genome analysis toolkit best practices pipeline. Current Protocols in Bioinformatics. 2013:11.10, 11–11.10, 33. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1110s43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsuba C, Ostrow DG, Salomon MP, Tolani A, Baer CF. Temperature, stress and spontaneous mutation in Caenorhabditis briggsae and Caenorhabditis elegans. Biology letters. 2013;9:20120334. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2012.0334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu W, Suo F, Du L-L. Bulk segregant analysis reveals the genetic basis of a natural trait variation in fission yeast. Genome biology and evolution. 2015;7:3496–3510. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evv238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wood V, Harris MA, McDowall MD, Rutherford K, Vaughan BW, Staines DM, Aslett M, Lock A, Bähler J, Kersey PJ. PomBase: a comprehensive online resource for fission yeast. Nucleic acids research. 2011:gkr853. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kosarek JN, Woodruff RV, Rivera-Begeman A, Guo C, D'Souza S, Koonin EV, Walker GC, Friedberg EC. Comparative analysis of in vivo interactions between Rev1 protein and other Y-family DNA polymerases in animals and yeasts. DNA repair. 2008;7:439–451. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu VF, Bhaumik D, Wang TS-F. Mutator phenotype induced by aberrant replication. Molecular and cellular biology. 1999;19:1126–1135. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Slatkin M. A measure of population subdivision based on microsatellite allele frequencies. Genetics. 1995;139:457–462. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.1.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Putman AI, Carbone I. Challenges in analysis and interpretation of microsatellite data for population genetic studies. Ecology and evolution. 2014;4:4399–4428. doi: 10.1002/ece3.1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.