Abstract

Vascular function has been found to be impaired in patients with sickle cell disease (SCD). The present study investigated the determinants of systemic vascular resistance in two main SCD syndromes in children: sickle cell anemia (SCA) and sickle cell-hemoglobin C disease (SCC). Nitric oxide metabolites (NOx), hematological, hemorheological, and hemodynamical parameters were investigated in 61 children with SCA and 49 children with SCC. While mean arterial pressure was not different between SCA and SCC children, systemic vascular resistance (SVR) was greater in SCC children. Although SVR and blood viscosity (ηb) were not correlated in SCC children, the increase of ηb (+18%) in SCC children compared to SCA children results in a greater mean SVR in this former group. SVR was positively correlated with ηb, hemoglobin (Hb) level and RBC deformability, and negatively with NOx level in SCA children. Multivariate linear regression model showed that both NOx and Hb levels were independently associated with SVR in SCA children. In SCC children, only NOx level was associated with SVR. In conclusion, vascular function of SCC children seems to better cope with higher ηb compared to SCA children. Since the occurrence of vaso-occlusive like complications are less frequent in SCC than in SCA children, this finding suggests a pathophysiological link between the vascular function alteration and these clinical manifestations. In addition, our results suggested that nitric oxide metabolism plays a key role in the regulation of SVR, both in SCA and SCC.

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) patients are characterized by wide hemorheological alterations [36], which participate to the pathophysiological mechanisms of vaso-occlusion [1, 27, 32]. Sickle cell anemia (SCA) and sickle cell hemoglobin C disease (SCC) are the most frequent forms of SCD but they drastically differ in their hemorheological profile [36]. SCC patients usually exhibit moderate anemia as compared to SCA patients, a characteristic which explains why they exhibit blood hyper-viscosity in comparison with SCA patients or control population [36]. In the traditional view, it has long been postulated that conditions in which blood viscosity (ηb) is increased should be associated with increased vascular resistance and decreased tissue perfusion [11, 17].

The study of the relationship between ηb and systemic vascular resistance (SVR) may provide relevant information on the vascular function [15–16, 22, 39]. Counterintuitive data have been recently reported in animal models demonstrating that increment in ηb resulted in a paradoxical decrease of vascular resistance. This observation demonstrates that vascular function, if not impaired, is able to adapt to increased ηb, until a certain threshold, and thus modulating SVR [12–14]. Although some data support an impaired vascular function in SCA patients [6, 18], the vascular function of SCC patients has been poorly described up to now. We propose, in the present study, to explore the relationships between ηb and SVR in a group of SCA children and a group of SCC children. Since patients with SCC, despite their very high ηb [36], present an usually milder clinical course of the disease than SCA patients [26], we hypothesized that SVR should be less dependent on ηb in SCC patients than in SCA patients, indicating more preserved vascular control mechanisms in the former group than in the latter one.

In addition, it has been shown that nitric oxide (NO) metabolism is impaired in SCA [21] and may play a key role in the regulation of vascular function [6]. To our best knowledge, no study had investigated NO production in SCC so far. We tested the association of nitric oxide metabolites (NOx) level with SVR and we hypothesized that NO production should be lower in SCA than in SCC children.

Methods

Patients and Ethics statement

A total of 110 children with SCD aged from 8 to 16 yrs old were included in the study: 61 with SCA and 49 with SCC. All these children had been identified by neonatal sickle cell disease screening and thus have benefited, since birth, of medical follow-up at the Sickle Cell Center of the Academic Hospital of Pointe-à-Pitre (Guadeloupe). All of them were in steady-state condition at the time of their recruitment. The diagnosis of SCD was established by isoelectrofocusing (Multiphor II™ System, GE HEALTH CARE, Buck, UK), citrate agar electrophoresis, cation-exchange high performance liquid chromatography (VARIANT™, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) and confirmed by DNA studies for the SCA children [35]. Steady state was defined as a period without blood transfusions within the previous three months and the absence of acute episodes (infection, vaso-occlusive crisis, acute chest syndrome, stroke, priapism, splenic sequestration) for at least one month before enrolment in the study. Twenty-three percents of the SCA patients were under hydroxyurea (HU) therapy while no SCC patients received HU. NOx level, hemodynamical, hemorheological and hematological parameters were determined in all children. The painful vaso-occlusive (VOC) and acute chest syndrome (ACS) rates were calculated for each child by dividing the number of painful VOC or ACS episodes by the number of patient-years [32]. An acute event was scored as a VOC or ACS using the criteria previously published [20]. All the information regarding the VOC or ACS episodes have been collected retrospectively and independently by three physicians who were not aware of the biological and hemodynamical results.

The protocol was in accordance with the guidelines set by the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee (CPP Sud/Ouest Outre Mer III, Bordeaux, France; SAPOTILLE project, IRB number: 2009-A00211-56). All children were informed of the procedures and purposes of the study and all, as well as their parents, gave written informed consent.

Biological measurements

Venipuncture was performed between 8:00 a.m. and 10:00 a.m. EDTA blood samples were immediately used for measurements of hemoglobin concentration (Hb), hematocrit (Hct), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), percent of reticulocytes (RET), and red blood cell (RBC), platelet (PLT) and white blood cell (WBC) counts (Max M-Retic, Coulter, USA). The ηb was determined at native Hct, at 25°C and at a shear rate of 225 s−1 using a cone-plate viscometer (Brookfield DVII+ with CPE40 spindle, Brookfield Engineering Labs, Natick, MA). RBC deformability (Elongation Index; EI) was determined at 37°C and at 30 Pa by ektacytometry, using the Laser-assisted Optical Rotational Cell Analyzer (LORCA, RR Mechatronics, Hoorn, the Netherlands). Measurements were carried out within 4 hours following venipuncture to avoid blood rheological alterations [38]. Full oxygenation of blood was performed before the measurements using the methodological procedures recommended [4]. NOx levels were determined by measuring plasma concentrations of nitrate/nitrite (after the conversion of nitrate to nitrite utilizing nitrate reductase) with a colorimetric assay kit (Enzo Life Sciences, Villeurbanne, France).

Hemodynamical parameters

Systolic (SBP) and diastolic blood pressures (DBP) were manually measured at the brachial artery level and mean arterial pressure (MAP) was then calculated as: [(2 * DBP) + SBP]/3. Hemodynamical parameters were assessed by transthoracic echocardiography using Sonos IE33 machines (Philips Medical Systems, Andover, MA, USA). Heart rate (HR), stroke volume (SV) and cardiac output were determined. The cardiac output was corrected by the body surface for determination of the cardiac index (CI). Systemic vascular resistance (SVR) was then calculated by dividing MAP by CI and expressed in Wood Unit (WU). Since no right heart catheterization was possible in this study, SVR calculation did not take into account the right atrial pressure (i.e. central venous pressure), which is usually estimated to be around 5–10 mmHg in this population [29, 31].

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as means ± SD. Biological and hemodynamical parameters were compared between SCA and SCC children using an unpaired Student t test. Correlation analyses were performed using a Pearson test in the SCA and SCC groups. The significance level was defined as p < 0.05. Significant associations found between SVR and biological parameters for each group were then included in a multivariate linear regression model to test the independent associations between SVR and the biological variables. Analyses were conducted using Statistica (v. 5.5, Statsoft, USA).

Results

Anthropometric characteristics and acute complications

Mean age (11.5 ± 2.4 yrs and 12.0 ± 2.3 yrs in SCA and SCC children, respectively) and height (147 ± 15 cm and 153 ± 16 cm in SCA and SCC children, respectively) were not different between the two groups. SCA children (37.4 ± 11.6 kg) had lower weight than SCC children (44.8 ± 14.5 kg; p < 0.01). Mean VOC (p < 0.05) and ACS (p < 0.001) rates were significantly greater in SCA (0.44 ± 0.48 and 0.15 ± 0.22 episodes/yr, respectively) than in SCC children (0.26 ± 0.39 and 0.03 ± 0.06 episodes/yr, respectively).

Biological parameters

As expected, WBC and PLT counts, MCV, MCH, and RET values were higher in SCA children than in SCC children (p < 0.001; Table 1) while RBC count, Hb, Hct, ηb, RBC deformability (AI) and NOx levels were lower in the SCA group than in the SCC group (p < 0.01 or < 0.001; Table 1).

Table 1.

Hematological parameters and blood viscosity in SCD children

| SCA (n = 61) | SCC (n = 49) | |

|---|---|---|

| Hb (g.dl−1) | 7.9 ± 1.4 | 11.1 ± 1.0*** |

| Hct (%) | 23.0 ± 4.3 | 31.6 ± 2.7*** |

| MCV (fl) | 81.9 ± 8.4 | 71.7 ± 5.8*** |

| MCH (pg) | 28.1 ± 3.2 | 25.3 ± 2.4*** |

| RET (109.l−1) | 290 ± 117 | 128 ± 45*** |

| RBC (1012.l−1) | 2.8 ± 0.7 | 4.4 ± 0.5*** |

| WBC (109.l−1) | 11.2 ± 2.9 | 7.3 ± 2.8*** |

| PLT (109.l−1) | 457 ± 138 | 282 ± 134*** |

| ηb (mPa.s−1) † | 5.5 ± 1.4 | 6.7 ± 1.2*** |

| NOx (μmol.l−1) †† | 28.5 ± 9.7 | 33.7 ± 10.5** |

| EI (AU) ††† | 0.38 ± 0.11 | 0.45 ± 0.05*** |

Values are expressed as mean ± SD. Hb (hemoglobin concentration), Hct (hematocrit), MCV (mean corpuscular volume), MCH (mean corpuscular hemoglobin), RET (percent of reticulocytes), RBC (red blood cell count), WBC (white blood cell count), PLT (platelet count), LDH (lactate deshydrogenase), ηb (blood viscosity), NOx (nitric oxide metabolites) and EI (elongation index = RBC deformability).

Statistical difference (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001).

determined in 57 SCA and 47 SCC,

determined in 56 SCA and 49 SCC,

determined in 58 SCA and 49 SCC.

Hemodynamical parameters

Hemodynamical parameters are reported in the Table 2. Because SBP and DBP were not different between the two groups, MAP was similar in the SCA and SCC children (Table 2). Both SV (p < 0.01) and HR (p < 0.05) were greater in SCA children than in SCC children resulting in a greater CI (p < 0.001). SVR was lower in SCA patients compared to the SCC group (p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Hemodynamical parameters in SCD children

| SCA | SCC | |

|---|---|---|

| SBP (mmHg) | 108 ± 8 | 107 ± 9 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 66 ± 7 | 67 ± 8 |

| MAP (mmHg) | 94 ± 7 | 94 ± 7 |

| SV (ml) † | 72.0 ± 19.5 | 57.6 ± 18.7*** |

| HR (beats.min−1) † | 81 ± 10 | 74 ± 14* |

| CI (l.min−1.m−2) † | 5.8 ± 1.6 | 4.2 ± 1.1*** |

| SVR (AU) † | 17.4 ± 4.9 | 23.8 ± 5.7*** |

Values are expressed as mean ± SD. SBP (systolic blood pressure), DBP (diastolic blood pressure), MAP (Mean arterial pressure), SV (stroke volume), HR (heart rate), CI (cardiac index), SVR (systemic vascular resistance).

Statistical difference (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001).

determined in 49 SCA and 40 SCC

Correlation analyses

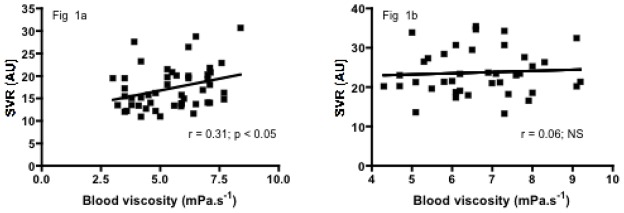

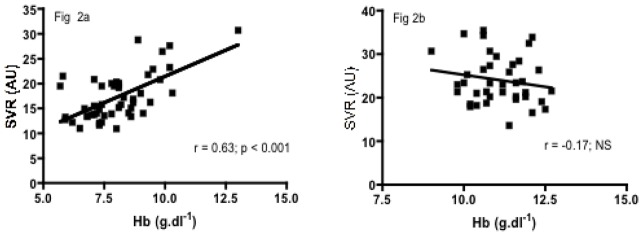

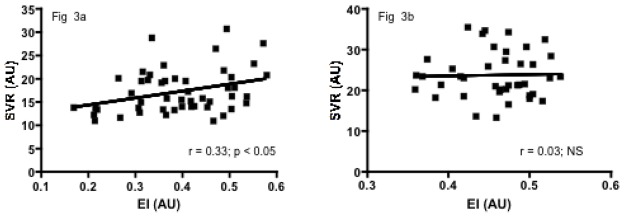

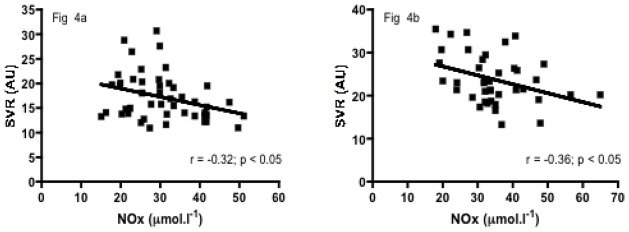

Significant positive correlations were observed between SVR and ηb, Hb level or RBC deformability in the SCA group (r = 0.31, p < 0.05, Figure 1a; r = 0.63, p < 0.001, Figure 2a; r = 0.33, p < 0.05, Figure 3a, respectively) but not in the SCC group (r = 0.06, p > 0.05; Figure 1b; r = −0.28, p > 0.05, Figure 2b; r = 0.03, p > 0.05, Figure 3b, respectively). Significant negative correlations were found in both SCA and SCC group between SVR and NOx (r = −0.32, p < 0.05, Figure 4a; r = −0.36, p < 0.05, Figure 4b, respectively). No significant correlation was observed between SVR and RET.

Figure 1.

Figure 1a. Relationship between SVR and ηb in SCA children

Figure 1b. Relationship between SVR and ηb in SCC children

Figure 2.

Figure 2a. Relationship between SVR and Hb level in SCA children

Figure 2b. Relationship between SVR and Hb level in SCC children

Figure 3.

Figure 3a. Relationship between SVR and RBC deformability (EI) in SCA children

Figure 3b. Relationship between SVR and RBC deformability (EI) in SCC children

Figure 4.

Figure 4a. Relationship between SVR and NOx in SCA children

Figure 4b. Relationship between SVR and NOx in SCC children

Multivariate linear regression model

In SCA children, the multivariate linear regression model included SVR as dependent variable and ηb, Hb level, RBC deformability and NOx level as covariates. The overall model was statistically significant (R2 = 0.55; p < 0.001) and only Hb and NOx levels remained significantly associated with SVR (beta = 0.74, p < 0.001 and beta = −0.30, p < 0.05, respectively). No multivariate linear regression model was performed in the SCC children since only SVR and NOx levels were associated (see above).

Discussion

The major findings of the present study are that 1) SCA children are characterized by lower Hb level, ηb and SVR than SCC children suggesting lower vascular stress in SCA than in SCC children but 2) SVR is positively correlated with ηb in SCA children and not in the SCC group demonstrating that the vascular system is able to better cope with high ηb in SCC than in SCA children to maintain SVR at a constant level. Finally, nitric oxide metabolism seems to be involved in the regulation of SVR in both SCA and SCC children.

As previously shown, the hematological and hemorheological characteristics of SCC and SCA children included in this study shown significant differences [2, 10, 20, 36] with marked anemia, leucocytosis, reticulocytosis, thrombocytosis, lower ηb at native hematocrit and reduced RBC deformability in the SCA group. Although SCC children had a 18% fold greater ηb and 27% fold greater SVR than SCA children, the two groups exhibited same SBP and DBP leading to similar MAP. This finding results from the fact that CI, as a consequence of severe anemia, was higher in SCA children in comparison with SCC children.

In healthy population, vascular geometry adapts to compensate for increased ηb, hence limiting the increase in SVR [28, 33, 39]. A rise in ηb has been shown to increase the wall shear stress applied to the endothelium level, which produces more vasodilators, such as NO, leading to compensatory vasodilation [8, 34, 37, 39]. Vazquez et al. [39] demonstrated that, in healthy controls, SVR and ηb were not correlated which strongly supports the concept that vascular function may easily compensate for the increase in ηb in healthy individuals. Since SCC children have elevated ηb and SVR compared to SCA group, it could be suggested that vascular function is more impaired in SCC children than in SCA children. But the positive correlation found between SVR and ηb in the SCA group only, suggests that vascular function is more impaired in SCA than in SCC; a situation also described in type 1 diabetes children [39]. Indeed, although the vascular stress is higher in SCC children (greater SVR), their vascular system is better able to cope with increased blood viscosity than in SCA children. Besides, a recent study performed on a subgroup of SCA and SCC children included in this study demonstrated that increased blood viscosity was a risk factor for VOC in SCA but not in SCC children [20]. In addition, Mohan et al. [23] reported that endothelium-dependent cutaneous vasodilation at the finger level was more impaired in SCA than in SCC disease suggesting, again, greater vascular dysfunction in SCA than in SCC.

Our results also demonstrated a negative correlation between SVR and NOx level, and positive correlations between SVR and Hb level or RBC deformability in SCA children. While it seems logic that lower NO production and higher Hb level (causing higher ηb) could induce greater SVR, the physiological meaning of the positive association between RBC deformability and SVR clearly deserves further explanation. Several experimental data have demonstrated that improved RBC deformability may cause a decrease of vascular resistance and facilitates blood flow [5, 30]. A decrease of RBC deformability may affect RBC velocity in the microcirculation, particularly when the blood pressure is lowered [9]. However, in the context of SCA [40], it is demonstrated that well deformable RBCs abnormally adhere to endothelial cells [24], hence impairing blood flow [19] and triggering VOC [3, 20]. Accordingly, the association between RBC deformability and SVR found in SCA children is not so surprising. Then, the multivariate linear regression analysis demonstrated that both Hb and NOx were independently associated with SVR in SCA children showing that both of these parameters play an independent and important role in determining SVR.

While neither ηb, nor Hb level was associated with SVR in SCC children, increased NOx level was accompanied by decreased SVR. Although the lack of association between SVR and ηb in SCC children suggests a more preserved vascular function in this population than in SCA children, their SVR seems to be very sensitive to the amount of NO produced as it is the case for SCA children. Any decrease in NO bioavailability caused by hemolysis [18] and oxidative stress [7] could be susceptible to increase blood flow resistance in SCC. NOx levels have been previously found to be associated with VOC and ACS occurrence in SCA [25]. Indeed, the lower NOx level observed in our SCA children compared to the SCC group could partly explain why SCA children had an average higher rate of VOC and ACS than SCC children.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that children with SCA have lower ηb resulting in a lower SVR than children with SCC. However, despite these differences, the vascular function of SCC children seems to be more preserved than the one of SCA children since SVR is not correlated with ηb in SCC children. This observation may provide a partial explanation to the lower frequency of the vaso-occlusive clinical complication observed in SCC compared to SCA children [26]. Nevertheless, the vascular function of both SCD syndromes seems to be sensitive to the amount of nitric oxide produced.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The study has been funded by a Projet Hospitalier Recherche Clinique (PHRC) Interregional. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. This work was also supported by European funds and the Conseil Régional de la Guadeloupe (fellowship to YL), as well as Inserm funding.

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- 1.Alexy T, Sangkatumvong S, Connes P, Pais E, Tripette J, Barthelemy JC, Fisher TC, Meiselman HJ, Khoo MC, Coates TD. Sickle cell disease: Selected aspects of pathophysiology, autonomic nervous system function and rheological considerations in transfusion therapy. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2010;44:155–166. doi: 10.3233/CH-2010-1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballas SK, Larner J, Smith ED, Surrey S, Schwartz E, Rappaport EF. The xerocytosis of Hb SC disease. Blood. 1987;69:124–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ballas SK, Smith ED. Red blood cell changes during the evolution of the sickle cell painful crisis. Blood. 1992;79:2154–2163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baskurt OK, Boynard M, Cokelet GC, Connes P, Cooke BM, Forconi S, Liao F, Hardeman MR, Jung F, Meiselman HJ, Nash G, Nemeth N, Neu B, Sandhagen B, Shin S, Thurston G, Wautier JL. New guidelines for hemorheological laboratory techniques. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2009;42:75–97. doi: 10.3233/CH-2009-1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baskurt OK, Yalcin O, Meiselman HJ. Hemorheology and vascular control mechanisms. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2004;30:169–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belhassen L, Pelle G, Sediame S, Bachir D, Carville C, Bucherer C, Lacombe C, Galacteros F, Adnot S. Endothelial dysfunction in patients with sickle cell disease is related to selective impairment of shear stress-mediated vasodilation. Blood. 2001;97:1584–1589. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.6.1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chirico EN, Pialoux V. Role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of sickle cell disease. IUBMB Life. 2012;64:72–80. doi: 10.1002/iub.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Damaske A, Muxel S, Fasola F, Radmacher MC, Schaefer S, Jabs A, Orphal D, Wild P, Parker JD, Fineschi M, Munzel T, Forconi S, Gori T. Peripheral hemorheological and vascular correlates of coronary blood flow. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2011;49:261–269. doi: 10.3233/CH-2011-1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Driessen GK, Fischer TM, Haest CW, Inhoffen W, Schmid-Schonbein H. Flow behaviour of rigid red blood cells in the microcirculation. Int J Microcirc Clin Exp. 1984;3:197–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fabry ME, Kaul DK, Raventos-Suarez C, Chang H, Nagel RL. SC erythrocytes have an abnormally high intracellular hemoglobin concentration. Pathophysiological consequences. J Clin Invest. 1982;70:1315–1319. doi: 10.1172/JCI110732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forconi S, Gori T. The evolution of the meaning of blood hyperviscosity in cardiovascular physiopathology: should we reinterpret Poiseuille? Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2009;42:1–6. doi: 10.3233/CH-2009-1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forconi S, Wild P, Munzel T, Gori T. Endothelium and hyperviscosity. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2011;49:487–491. doi: 10.3233/CH-2011-1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gori T. Viscosity, platelet activation, and hematocrit: Progress in understanding their relationship with clinical and subclinical vascular disease. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2011;49:37–42. doi: 10.3233/CH-2011-1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hightower CM, Salazar Vazquez BY, Woo Park S, Sriram K, Martini J, Yalcin O, Tsai AG, Cabrales P, Tartakovsky DM, Johnson PC, Intaglietta M. Integration of cardiovascular regulation by the blood/endothelium cell-free layer. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2011;3:458–470. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffman JI. Pulmonary vascular resistance and viscosity: the forgotten factor. Pediatr Cardiol. 2011;32:557–561. doi: 10.1007/s00246-011-9954-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Intaglietta M. Increased blood viscosity: disease, adaptation or treatment? Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2009;42:305–306. doi: 10.3233/CH-2009-1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jung F, Mrowietz C, Hiebl B, Franke RP, Pindur G, Sternitzky R. Influence of rheological parameters on the velocity of erythrocytes passing nailfold capillaries in humans. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2011;48:129–139. doi: 10.3233/CH-2011-1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kato GJ, Hebbel RP, Steinberg MH, Gladwin MT. Vasculopathy in sickle cell disease: Biology, pathophysiology, genetics, translational medicine, and new research directions. Am J Hematol. 2009;84:618–625. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaul DK, Fabry ME. In vivo studies of sickle red blood cells. Microcirculation. 2004;11:153–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lamarre Y, Romana M, Waltz X, Lalanne-Mistrih ML, Tressieres B, Divialle-Doumdo L, Hardy-Dessources MD, Vent-Schmidt J, Petras M, Broquere C, Maillard F, Tarer V, Etienne-Julan M, Connes P. Hemorheological risk factors of acute chest syndrome and painful vaso-occlusive crisis in children with sickle cell disease. Haematologica. 2012 doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.066670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lopez BL, Kreshak AA, Morris CR, Davis-Moon L, Ballas SK, Ma XL. L-arginine levels are diminished in adult acute vaso-occlusive sickle cell crisis in the emergency department. Br J Haematol. 2003;120:532–534. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martini J, Carpentier B, Negrete AC, Frangos JA, Intaglietta M. Paradoxical hypotension following increased hematocrit and blood viscosity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H2136–2143. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00490.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohan JS, Lip GY, Blann AD, Bareford D, Marshall JM. Endothelium-dependent and endothelium-independent vasodilatation of the cutaneous circulation in sickle cell disease. Eur J Clin Invest. 2011;41:546–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2010.02444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohandas N, Evans E. Adherence of sickle erythrocytes to vascular endothelial cells: requirement for both cell membrane changes and plasma factors. Blood. 1984;64:282–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris CR, Kuypers FA, Larkin S, Vichinsky EP, Styles LA. Patterns of arginine and nitric oxide in patients with sickle cell disease with vaso-occlusive crisis and acute chest syndrome. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2000;22:515–520. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200011000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagel RL, Steinberg MH. Hemoglobin SC disease and HbC disorders. In: Steinberg MH, Forget BG, Higgs DR, Nagel RL, editors. Disorders of hemoglobin: genetics, pathophysiology and clinical management. Cambridge University Press; 2001. pp. 756–785. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nebor D, Bowers A, Hardy-Dessources MD, Knight-Madden J, Romana M, Reid H, Barthelemy JC, Cumming V, Hue O, Elion J, Reid M, Connes P. Frequency of pain crises in sickle cell anemia and its relationship with the sympatho-vagal balance, blood viscosity and inflammation. Haematologica. 2011;96:1589–1594. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.047365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohlmann P, Jung F, Mrowietz C, Alt T, Alt S, Schmidt W. Peripheral microcirculation during pregnancy and in women with pregnancy induced hypertension. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2001;24:183–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parent F, Bachir D, Inamo J, Lionnet F, Driss F, Loko G, Habibi A, Bennani S, Savale L, Adnot S, Maitre B, Yaici A, Hajji L, O’Callaghan DS, Clerson P, Girot R, Galacteros F, Simonneau G. A hemodynamic study of pulmonary hypertension in sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:44–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1005565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parthasarathi K, Lipowsky HH. Capillary recruitment in response to tissue hypoxia and its dependence on red blood cell deformability. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:H2145–2157. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.6.H2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pashankar FD, Carbonella J, Bazzy-Asaad A, Friedman A. Prevalence and risk factors of elevated pulmonary artery pressures in children with sickle cell disease. Pediatrics. 2008;121:777–782. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Platt OS, Thorington BD, Brambilla DJ, Milner PF, Rosse WF, Vichinsky E, Kinney TR. Pain in sickle cell disease. Rates and risk factors. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:11–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199107043250103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salazar Vazquez BY. Blood pressure and blood viscosity are not correlated in normal healthy subjects. Vasc Health Risk Manag. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S27415. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smieško V, Johnson PC. The arterial lumen is controlled by flow related shear stress. News Physiol Sci. 1993;8:34–38. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tarer V, Etienne-Julan M, Diara JP, Belloy MS, Mukizi-Mukaza M, Elion J, Romana M. Sickle cell anemia in Guadeloupean children: pattern and prevalence of acute clinical events. Eur J Haematol. 2006;76:193–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2005.00590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tripette J, Alexy T, Hardy-Dessources MD, Mougenel D, Beltan E, Chalabi T, Chout R, Etienne-Julan M, Hue O, Meiselman HJ, Connes P. Red blood cell aggregation, aggregate strength and oxygen transport potential of blood are abnormal in both homozygous sickle cell anemia and sickle-hemoglobin C disease. Haematologica. 2009;94:1060–1065. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2008.005371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsai AG, Acero C, Nance PR, Cabrales P, Frangos JA, Buerk DG, Intaglietta M. Elevated plasma viscosity in extreme hemodilution increases perivascular nitric oxide concentration and microvascular perfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H1730–1739. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00998.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Uyuklu M, Cengiz M, Ulker P, Hever T, Tripette J, Connes P, Nemeth N, Meiselman HJ, Baskurt OK. Effects of storage duration and temperature of human blood on red cell deformability and aggregation. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2009;41:269–278. doi: 10.3233/CH-2009-1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vazquez BY, Vazquez MA, Jaquez MG, Huemoeller AH, Intaglietta M, Cabrales P. Blood pressure directly correlates with blood viscosity in diabetes type 1 children but not in normals. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2010;44:55–61. doi: 10.3233/CH-2010-1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wautier JL, Wautier MP. Molecular basis of erythrocyte adhesion to endothelial cells in diseases. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2012 doi: 10.3233/CH-2012-1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]