Abstract

Background

Blood based testing can be used as a non-invasive method to recover and analyze circulating tumor derived cells for clinical use. Circulating Cancer Associated Macrophage-Like cells (CAML) are specialized myeloid cells found in peripheral blood and associated with the presence of solid malignancies. We measured CAMLs prospectively in peripheral blood to ascertain their prevalence, specificity, and sensitivity in relation to breast disease status at clinical presentation.

Methods

We report on two related but separate studies: 1) CellSieve™ microfilters were used to isolate CAMLs from blood samples of patients with known malignant disease (n=41). Prevalence and specificity was compared against healthy volunteers (n=16). 2) A follow-up double blind pilot study was conducted on women (n=41) undergoing core needle biopsy to diagnose suspicious breast masses.

Results

CAMLs were found in 93% of known malignant patients (n=38/41), averaging 19.4 cells/sample, but none in the healthy controls. In subjects undergoing core biopsy for initial diagnosis, CAMLs were found in 88% of subjects with invasive carcinoma (n=15/17) and 26% with benign breast conditions (n=5/19).

Conclusion

These preliminary pilot studies suggest that the presence of CAMLs may differentiate patients with malignant disease, benign breast conditions, and healthy individuals.

Impact

We supply evidence that this previously unidentified circulating stromal cell may have utility as a screening tool to detect breast cancer in various malignancies, irrespective of disease stage.

Keywords: Circulating Stromal Cells, Circulating Cancer Associated Macrophage-Like Cells, Blood Based Biopsy, Early detection of breast cancer, Cancer screening

Introduction

Blood-based biopsies, i.e. “liquid” biopsies, using the peripheral blood of cancer patients have identified various tumor-associated circulating cells, including circulating tumor/epithelial cells (CTCs) and cancer associated macrophage-like cells (CAMLs) (1–3). CTCs are malignant cells derived from solid tumors and may enter the circulatory system after dissociating from their original tumor site (4). CAMLs are clearly distinct from CTCs as they have properties of phagocytic myeloid cells and may be derived from an immunological response to the tumor (5). In both cases, these cells should be an indication of the presence of cancer and the extent of disease burden, particularly metastatic disease (6–8). However, CTCs are rarely found in non-metastatic disease and do not provide the sensitivity needed for early detection although their presence in early stage disease may be prognostic (9). In contrast, CAMLs appear to be more prevalent in all cancer patients, regardless of stage, but their underlying biology and clinical utility are still undetermined (5).

CAMLs are specialized myeloid cells (CD14+) that are found transiting the circulation of patients in all stages of cancer and in a variety of malignancies (5). Based on our preliminary studies, these cells are responsive to cancer treatment and are linked with poor prognosis in pancreatic, prostate, and breast cancer (5, 10, 11). Initially observed many years ago in both circulation and in tumor masses (12–16), the clinical value of these cells for detecting, staging, or monitoring malignancies has not been tested. We and others have previously reported that size-based filtration can rapidly and efficiently isolate multiple varieties of circulating tumor associated cells (5, 17), including CAMLs and CTCs, from peripheral blood. It is therefore possible to study both cell types in conjunction with and in relation to malignant or benign conditions.

Our approach employs CellSieve™ microfilters that are lithographically fabricated membranes with high porosity, precise pore dimensions, and regular pore distribution to isolate peripheral blood cells larger than 7 µm. In this report, we describe two separate but related prospective studies using our CAML isolation and analysis procedures in the context of breast cancer detection. Results from these studies suggest that this circulating stromal cell occurs as an early event in the progression of the disease and may have utility as a non-invasive tool to differentiate breast cancer from benign breast conditions.

Materials and Methods

Anonymized peripheral blood samples (n=41) were supplied through collaborative agreements with Fox Chase Cancer Center (FCCC) and University of Maryland Baltimore (UMB) with written informed consent and according to the local IRB approval at each institution. The 41 whole peripheral blood samples were drawn from women who were actively undergoing treatment for previously confirmed stage II, III or IV breast cancer at either FCCC or UMB between 2011 and 2013. The study group characteristics can be found in Supplementary Table 1. All blood samples were drawn into CellSave preservative tubes™ (~9mL, Janssen Diagnostics) and shipped to Creatv MicroTech (Creatv) for processing. Results and patient identification from institutions were not shared or communicated until completion of study.

Anonymized healthy women volunteers donated blood samples (n=16) with written informed consent and IRB approval by Western Institutional Review Board. Donor samples were procured on a voluntarily basis at a blood collection center with no selection process, outside standard exclusion criteria. As such, all samples were considered to be from healthy individuals and were drawn into CellSave preservative tubes™ and shipped to Creatv for processing. The 41 cancers and 16 healthy controls constitute Study A in this report (Figure 1A).

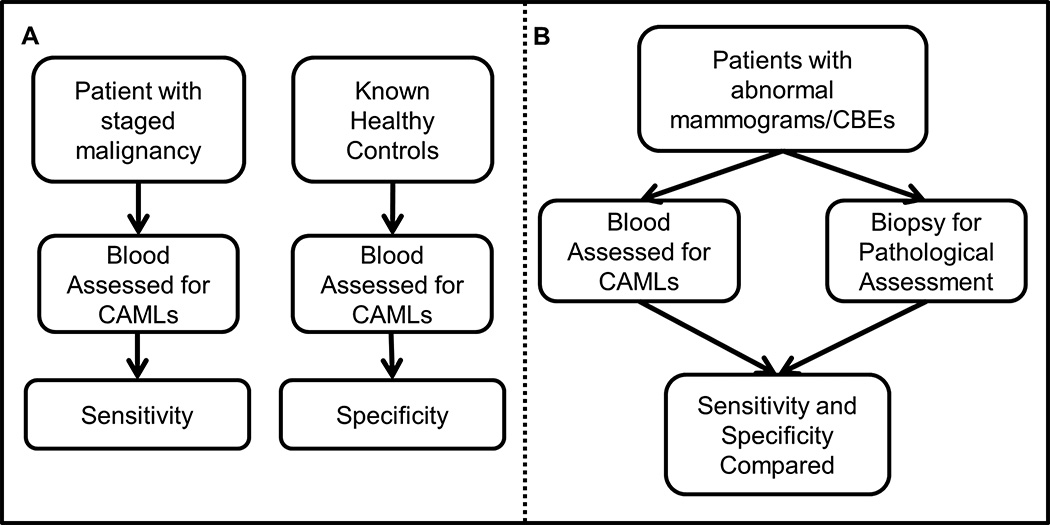

Figure 1. Overview of sensitivity and specificity determination based on our two studies, either Study A: populations of women with diagnosed breast cancer or Study B: populations of women with positive Clinical Breast Exam (CBE)/mammography but before diagnosis.

(A) Patients with invasive breast malignancy were used to determine sensitivity of an assay based on CAML presence. Healthy controls were used to determine the specificity. (B) The assay was then tested using patients with positive breast mammography, or positive CBEs, for CAML presence by standard blood draw at the time core biopsy was taken. Standard pathological assessment was used to determine invasive malignant disease, benign condition, or non-invasive disease/Stage 0. Patient information was then unblinded and sensitivity/specificity of CAMLs in relation to pathological assessment was compared.

Study B was a double-blind prospective study of peripheral blood samples from 41 subjects undergoing tissue diagnosis by needle core biopsy, performed as a collaboration between Duke University Medical Center and Creatv (Figure 1B). Blood was procured from subjects undergoing core biopsy, either immediately before or immediately after core biopsy (see Table 1), after referral from either an abnormal screening mammogram or clinical exam and were shipped overnight to Creatv for processing. Investigators at Duke University, Creatv and the subjects themselves were unaware of the pathologic diagnosis at the time of the blood draw and CAML analysis. Follow-up information derived from pathology reports on the core biopsy and subsequent surgeries (if performed) were collected. This information was only shared with investigators at Creatv after CAML analysis was performed and returned to Duke.

Table 1.

Subject Characteristics from study B: Patients with abnormal mammogram, or CBE.

| Benign (n=19) | ADH+DCIS (n=5) | Invasive (n=17) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean) | 55.2 | 58.4 | 57.1 |

| Race (n) | |||

| White | 14 | 5 | 16 |

| Black | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Asian | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Body Mass Index (mean) | 28.7 | 26.0 | 31.8 |

| Prior Invasive Cancer (%) | 0 | 0 | 6%a |

| Detected by Screening Mammography | 58%b | 80% | 35%c |

| Detected by Self-Exam | 37% | 20% | 53% |

| Drawn Before Biopsy (%) | 32% | 0% | 29% |

One of the invasive breast cancer subjects had an early invasive breast cancer diagnosed >20 years before the current encounter.

One of the subjects with a benign breast condition was referred for biopsy from an incidental finding from a CT exam

Two of the subjects with invasive cancer were referred based on findings from CT and PET exams

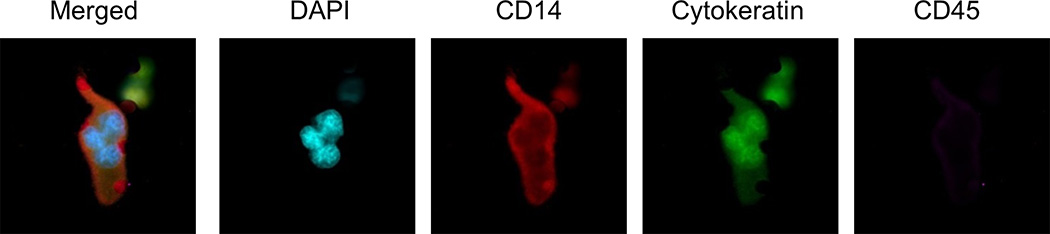

CellSieve™ microfilters were used to isolate CAMLs and CTCs from 7.5 mL of whole peripheral blood, using 7 µm pores to separate CAMLs from white blood cells (WBCs) based on size as previously described (18–20). CAMLs collected for Study A were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with DAPI and an antibody cocktail against cytokeratins 8, 18 and 19, EpCAM and CD45. CAMLs collected for Study B were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with DAPI and an antibody cocktail against cytokeratin 8, 18 and 19, CD14, and CD45. CAMLs were defined as enlarged (≥30µm in diameter), multinuclear cells with diffuse cytoplasmic cytokeratin and either CD14 positive or CD45 positive. As previously described, pathologically definable CTCs were defined as filamentous cytokeratin positive cells, with pleomorphic nuclei that were negative for CD45 and CD14 (Figure 2)(20). Epithelial-mesenchymal transition CTCs (EMT-CTCs) were defined as diffuse/non-filamentous cytokeratin positive cells with pleomorphic nuclei that were negative for CD45 and CD14(20).

Figure 2. Appearance of CAMLs isolated on filters from cancer patients.

Single ~100 µm CAML from a breast cancer patient with a polymorphonuclear DAPI stained structure (blue), intense CD14 (red) staining, some cytokeratin staining (green) and weak CD45 (purple). Box size=100 µm.

Results

Prevalence of CAMLs in Advanced Stage Breast Cancer Compared to Healthy Controls (Study A)

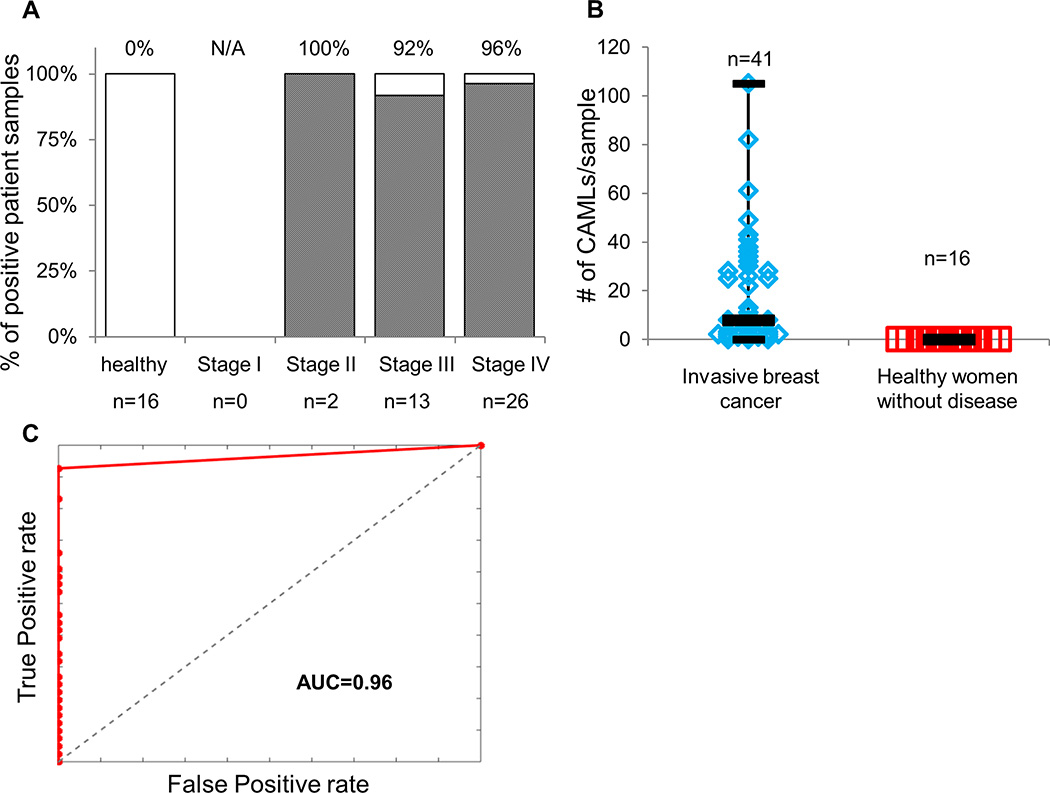

Our initial studies on several types of carcinomas indicated that the number of CAMLs may be related to stage of disease and response to therapy (5). To further explore this relationship specifically in breast cancer, we analyzed blood from 41 patients with known invasive breast cancer who were undergoing treatment for the disease. CAMLs were found in 93% of blood samples (Figure 3A). Specifically, CAMLs averaged 19.4 per 7.5 mL blood sample (2.6 CAML/mL), median 8.0 per sample, low of 0 per sample, and a high of 105 per sample (Figure 3B and Supplementary Table 1). We compared these findings to a group of healthy women of comparable age with no known malignant conditions. No CAMLs were detected in any of the 16 peripheral blood samples from these control subjects (Figure 3). Therefore, using a threshold of 1 CAML as a positive finding, the results from Study A are summarized by an receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.96 (CI95% 0.91–1.0) (Figure 3C) with sensitivity of 93% (CI95% 80–99%), specificity of 100% (CI95% 79–100%), positive predictive value (PPV 100% (CI95% 91–100%), and negative predictive value (NPV): 84% (CI95% 60–97%).

Figure 3. Study A: Presence, sensitivity and specificity of CAMLs in patients with known invasive breast cancer versus healthy control volunteers.

(A) CAMLs were found in 38 of 41 patients with known invasive breast cancer, but in none of the 16 healthy controls. (B) The number of CAMLs ranged 0–105 per 7.5 mL blood sample in patients with cancer. (C) ROC curve shows a clear stratification between a healthy control population from a malignant population, AUC=0.96. Sensitivity: 93% (CI95% 80–99%) Specificity: 100% (CI95% 79–100%) PPV: 100% (CI95% 91–100%) NPV: 84% (CI95% 60–97%).

Detection of CAMLs in Women Undergoing Breast Cancer Diagnosis (Study B)

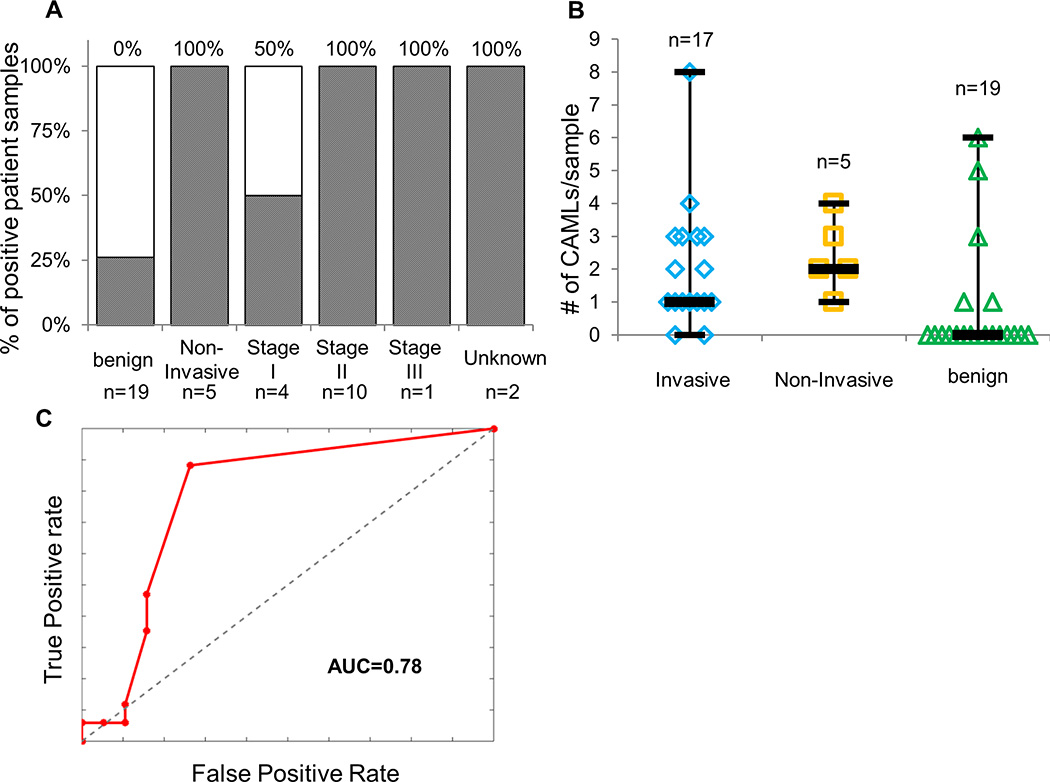

To determine the utility of CAMLs for detection and discrimination of cancer from benign conditions, we performed a PRoBE (21) designed prospective study by recruiting women undergoing image-guided biopsies for breast cancer diagnosis. Principles of PRoBE design are a prospective study that mirrors the population of subjects for which the test is designed followed by a blinded evaluation. In this case, all parties were blinded to the case-control status including the subjects who were having a tissue sampling procedure for the purposes of diagnosis. From 41 total subjects recruited over the course of a 6 month period (October 2014 – April 2015), CAMLs were detected in 15 of 17 subjects newly diagnosed with invasive breast cancer (88% sensitivity) (Figure 4A and Supplementary Table 2). In general, fewer CAMLs were detected in the subjects undergoing diagnosis compared to those under treatment (Study A). From a total of 19 patients diagnosed with benign breast conditions, CAMLs were detected in 5 (26%) subjects. In addition, 5/5 subjects who were diagnosed with high-risk non-invasive conditions (ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), stage 0 and atypical ductal hyperplasia) had detectable CAMLs (Figure 4B and Table 1). We saw no statistical difference in CAML size, morphology, or staining pattern between true positives and false positives. Comparing subjects with benign conditions (n=19, excluding the high risk non-invasive lesions) to those with invasive carcinoma (n=17) results in an ROC curve with an AUC of 0.78 (CI95% 0.63–0.92), using a threshold of 1 CAML as a positive finding (Figure 4C). This threshold returns a sensitivity of 88% (CI95% 64–99%), specificity of 74% (CI95% 49–91%), PPV of 75% (CI95% 51–91%), and a NPV of 88% (CI95% 62–99%), Supplementary Table 3.

Figure 4. Study B: Presence, sensitivity and specificity of CAMLs in patients with positive mammograms/CBEs compared to standard pathological assessment.

(A) CAMLs were found in all patients with non-invasive disease/Stage 0, in 88% of patients with invasive disease, and 26% of patients with benign conditions. (B) CAMLs were found in a range of 0–8 cells per 7.5 mL sample. (C) ROC curves comparing invasive breast cancer (n=17) to benign conditions (n=19) showed an AUC=0.78. Sensitivity: 88% (CI95% 64–99%) Specificity: 74% (CI95% 49–91%) PPV: 75% (CI95% 51–91%) NPV: 88% (CI95% 62–99%).

Aggregating the results from both studies shows that all breast cancer subtypes based on ER, PR, and HER2 status produce detectable levels of CAMLs and that there is not a pronounced effect of tumor stage or nodal status on the presence of these cells.

In comparison, for study A none of the healthy control samples had any type of detectable CTCs, as previously defined(20), but 76% of patients with known breast carcinomas had at least 1 pathologically definable CTC and 54% had at least 1 EMT-like CTC. In study B, none of the samples had pathologically definable CTCs, while EMT-like CTCs were found in 18% (n=3/17) of invasive carcinomas and in 37% (n=7/19) of patients with benign conditions (Supplementary Figure 1). The finding that no pathologically definable CTC was found in any patient sample with early disease, while EMT-like CTCs were found in 18% of patients, is on par with previous studies comparing CTCs in early stage disease. A variety of studies have shown that CTC isolation techniques may identify CTCs in ~20% of early stage disease(9, 22) while having a false positive rate of 7.5%-19%, compared to individuals with benign conditions(23, 24).

Discussion

There has been a great deal of interest in using blood-based biopsies, or so called “liquid biopsies” to diagnose, categorize, and monitor disease status in clinical oncology settings (3). One approach for isolating cancer associated cells from the peripheral blood is microfiltration which takes advantage of the typically larger size of these cells compared to the vast majority of the mononuclear cells found in circulation. Microfiltration has been shown to capture a variety of circulating tumor-derived cells, i.e. CTCs and CAMLs, without relying on specific cell surface markers for antibody capture. CAMLs have properties that are consistent with disseminated tumor associated macrophages containing phagocytosed elements of the primary tumor and as such may be specific and sensitive for the presence of cancer. We have identified these cells in multiple cancer types and at all stages of disease (5).

In this report, we describe two related studies to determine the prevalence and specificity of CAMLs for detecting breast cancer in independent populations of women undergoing diagnosis or treatment for the disease. Laboratory, evaluation methods, and criteria used to identify and enumerate CAMLs were nearly identical for both studies. In the first study, women with already diagnosed advanced stage breast cancer were compared to healthy age matched controls. Nearly all of the cases (n=38/41) and none of the controls (n=0/16) had detectable CAMLs yielding an AUC of 0.96. This degree of specificity and sensitivity support our prior work that the presence of CAMLs may be useful for disease monitoring(5, 10, 11). Further, the high fraction of positive cases, even in stage II cancers, shows the potential utility over current cell-based liquid biopsy methods which are limited by cell surface antigen expression required for antibody enrichment (20).

The second study was designed to test whether the presence of CAMLs could be useful in the diagnostic setting. There are a large number of breast biopsies performed each year in the United States after referral from imaging, clinical exam, or self-exam. The majority of these biopsies return benign findings resulting in no useful clinical recommendations other than continued surveillance. A cohort of women undergoing image-guided tissue diagnosis was enrolled in the study and blood was drawn either immediately before or immediately after the core biopsy procedure. Pathology and staging information were obtained in the weeks after enrollment and remained blinded to the scientists performing the CAML assay. This rigorous study design with an abundance of early stage newly diagnosed cancers still produced a meaningful but less dramatic separation between invasive cancers and benign conditions (AUC = 0.78). Interestingly, all 5 subjects with non-invasive breast disease (carcinoma in situ and atypical hyperplasia) had detectable CAMLs, suggesting that these high risk (25–27) conditions may cause an influx of CAMLs into circulation. As this was a prospective study, we have only a short interval of follow-up and none of these subjects have been diagnosed with invasive cancer within this limited time period.

While our study in women undergoing diagnosis contains appropriately matched cases and controls, we identify one caveat to the results. It is formally possible that the core biopsy itself produced a transient increase in CAML type cells. To account for this possibility, we compared the timing of blood draw in relation to the biopsy. In study B, approximately 70% of the subjects had their blood drawn immediately after the biopsy procedure with the remaining 30% drawn immediately before the biopsy (Supplementary Figure 2). In comparing the data set we did not observe a consistent trend in presence or number of CAMLs and the timing of the sample draw in relation to biopsy.

It has been argued that cancer screening assays should meet a minimum sensitivity and a minimum specificity, though usually screening assays will sacrifice specificity for sensitivity, or vice versa. Many would agree that >90% sensitivity and >90% specificity is optimal if cancer screening platforms are to be clinically useful. These data suggest that the presence of CAML cells as a tool for cancer screening may meet the desired sensitivity (93%) and specificity (100%), when persons with breast carcinomas are compared against a healthy population. However, comparing patients with carcinoma versus persons with benign conditions, while the sensitivity remains high (88%), the specificity drops to 74%. This was tested in patients where the current screening tools were unable to differentiate carcinomas and benign conditions, i.e. patients with a positive mammography exam, or breast exam. In this context, this study appears promising and dictates the need for additional biological and clinical studies to expand our understanding of CAMLs for its potential utility as a screening tool.

These studies, though preliminary and on relatively small sets of subjects, indicate that the use of CAMLs as a blood based biomarker of malignant disease shows promise. The high frequency and high specificity of CAMLs suggest a possible use as a biomarker for early detection of solid tumors including breast cancer. Additionally, further proteomic and genomic characterization of CAMLs may allow for more discrete identification of cancer type during initial disease screening and a more accurate differentiation of benign diseases. An expanded study cohort should include 1) a larger population of patients, 2) more patient subsets with and without malignant disease, 3) the inclusion of women with other conditions and 4) reading samples at multiple site to better gauge the inter-assay and inter-observer variability. Though this pilot study appears promising, the additional studies described will be necessary to fully assess the clinical utility of this cellular biomarker.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all of the patients and all of the healthy volunteers who contributed to this study. We also thank M. Charpentier and S. Stefansson for their technical support. The authors would also like to thank Elizabeth Wildermann and Cynthia Webb for their excellent clinical and technical support. The content of the information does not necessarily reflect the position or the policy of the US Government.

Financial Support: DL Adams and CM Tang were supported by a Maryland TEDCO MTTCF award. SS Martin was supported by grants R01-CA154624 from the National Cancer Institute, KG100240 from the Susan G. Komen Foundation, and a grant from an Era of Hope Scholar award from the Department of Defense (BC100675). DL Adams and CM Tang were supported by a grant from the U.S. Army Research Office (ARO) and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) (W911NF-14-C-0098). JR Marks was supported by a National Cancer Institute grant from the Early Detection Research Network, UO1 CA084955.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest:

CM Tang and D Adams have filed a patent application regarding this work. D. Adams and CM. Tang and are employees at Creatv Microtech, Inc.

Supplementary Information is available in the online version of the paper.

References

- 1.Plaks V, Koopman CD, Werb Z. Cancer. Circulating tumor cells. Science. 2013;341:1186–1188. doi: 10.1126/science.1235226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu M, Stott S, Toner M, Maheswaran S, Haber DA. Circulating tumor cells: approaches to isolation and characterization. The Journal of cell biology. 2011;192:373–382. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201010021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayes DF, Smerage JB. Circulating tumor cells. Progress in molecular biology and translational science. 2010;95:95–112. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385071-3.00005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fehm T, Sagalowsky A, Clifford E, Beitsch P, Saboorian H, Euhus D, et al. Cytogenetic evidence that circulating epithelial cells in patients with carcinoma are malignant. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:2073–2084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adams DL, Martin SS, Alpaugh RK, Charpentier M, Tsai S, Bergan RC, et al. Circulating giant macrophages as a potential biomarker of solid tumors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:3514–3519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320198111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bidard FC, Peeters DJ, Fehm T, Nole F, Gisbert-Criado R, Mavroudis D, et al. Clinical validity of circulating tumour cells in patients with metastatic breast cancer: a pooled analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Oncology. 2014;15:406–414. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wendel M, Bazhenova L, Boshuizen R, Kolatkar A, Honnatti M, Cho EH, et al. Fluid biopsy for circulating tumor cell identification in patients with early-and late-stage non-small cell lung cancer: a glimpse into lung cancer biology. Physical biology. 2012;9 doi: 10.1088/1478-3967/9/1/016005. 016005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pierga JY, Hajage D, Bachelot T, Delaloge S, Brain E, Campone M, et al. High independent prognostic and predictive value of circulating tumor cells compared with serum tumor markers in a large prospective trial in first-line chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:618–624. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lucci A, Hall CS, Lodhi AK, Bhattacharyya A, Anderson AE, Xiao L, et al. Circulating tumour cells in non-metastatic breast cancer: a prospective study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:688–695. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70209-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adams D, Alpaugh R, Cristofanilli M, Martin S, Chumsri S, Bergen R, et al. Cancer associated macrophage-like cells as a blood-based biomarker for the screening of solid tumors. Proceedings of the 106th Annual Meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research; 2015 Apr 18–22; Philadelphia, PA Philadelphia (PA); AACR. Cancer Res. 2015;75 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adams D, Bergan R, Martin S, Chumsri S, Charpentier M, Lapidus R, et al. Correlation of cancer-associated macrophage-like cells with systemic therapy and pathological stage in numerous malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33 (suppl; abstr 11095) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hume R, West JT, Malmgren RA, Chu EA. Quantitative Observations of Circulating Megakaryocytes in the Blood of Patients with Cancer. N Engl J Med. 1964;270:111–117. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196401162700301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Aster JC. Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang S, Mercado-Uribe I, Hanash S, Liu J. iTRAQ-based proteomic analysis of polyploid giant cancer cells and budding progeny cells reveals several distinct pathways for ovarian cancer development. PLoS One. 2013;8:e80120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang S, Mercado-Uribe I, Xing Z, Sun B, Kuang J, Liu J. Generation of cancer stem-like cells through the formation of polyploid giant cancer cells. Oncogene. 2014;33:116–128. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malpica A, Deavers MT, Lu K, Bodurka DC, Atkinson EN, Gershenson DM, et al. Grading ovarian serous carcinoma using a two-tier system. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2004;28:496–504. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200404000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vona G, Sabile A, Louha M, Sitruk V, Romana S, Schutze K, et al. Isolation by size of epithelial tumor cells : a new method for the immunomorphological and molecular characterization of circulating tumor cells. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:57–63. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64706-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adams DL, Zhu P, Makarova OV, Martin SS, Charpentier M, Chumsri S, et al. The systematic study of circulating tumor cell isolation using lithographic microfilters. RSC advances. 2014;9:4334–4342. doi: 10.1039/C3RA46839A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adams DL, Alpaugh RK, Martin SS, Charpentier M, Chumsri S, Cristofanilli M, et al. Precision microfilters as an all in one system for multiplex analysis of circulating tumor cells. RSC advances. 2016;6:6405–6414. doi: 10.1039/c5ra21524b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adams DL, Stefansson S, Haudenschild C, Martin SS, Charpentier M, Chumsri S, et al. Cytometric characterization of circulating tumor cells captured by microfiltration and their correlation to the cellsearch((R)) CTC test. Cytometry Part A : the journal of the International Society for Analytical Cytology. 2015;87:137–144. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.22613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pepe MS, Feng Z, Janes H, Bossuyt PM, Potter JD. Pivotal evaluation of the accuracy of a biomarker used for classification or prediction: standards for study design. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1432–1438. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rack B, Schindlbeck C, Juckstock J, Andergassen U, Hepp P, Zwingers T, et al. Circulating tumor cells predict survival in early average-to-high risk breast cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106 doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Franken B, de Groot MR, Mastboom WJ, Vermes I, van der Palen J, Tibbe AG, et al. Circulating tumor cells, disease recurrence and survival in newly diagnosed breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14:R133. doi: 10.1186/bcr3333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller MC, Doyle GV, Terstappen LW. Significance of Circulating Tumor Cells Detected by the CellSearch System in Patients with Metastatic Breast Colorectal and Prostate Cancer. Journal of oncology. 2010;2010:617421. doi: 10.1155/2010/617421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hartmann LC, Sellers TA, Frost MH, Lingle WL, Degnim AC, Ghosh K, et al. Benign breast disease and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:229–237. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solin LJ, Gray R, Baehner FL, Butler SM, Hughes LL, Yoshizawa C, et al. A multigene expression assay to predict local recurrence risk for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:701–710. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kerlikowske K, Molinaro AM, Gauthier ML, Berman HK, Waldman F, Bennington J, et al. Biomarker expression and risk of subsequent tumors after initial ductal carcinoma in situ diagnosis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:627–637. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.