Abstract

Purpose

This study evaluated the discriminatory power of salivary transcriptomic and proteomic biomarkers in distinguishing oral cancer (OSCC) cases from controls and potentially malignant oral disorders (PMOD).

Experimental design

A total of 180 samples (60 OSCC patients, 60 controls and 60 PMOD patients) were used in the study. Seven transcriptomic markers (IL-8, IL-1β, SAT1, OAZ1, DUSP1, S100P, H3F3A) were measured using quantitative real time PCR and two proteomic markers (IL-8 and IL-1β) were evaluated by ELISA.

Results

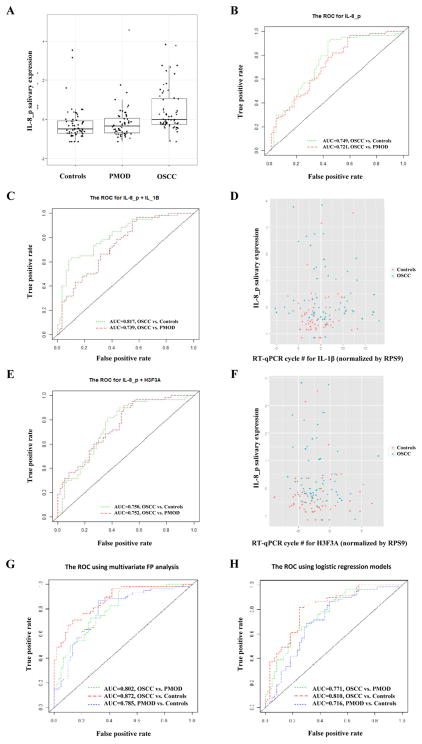

Among 7 transcriptomic markers, transcript level of DUSP1 was significantly lower in OSCC patients than in controls and PMOD patients. Between the proteomic markers, the protein concentration of IL-8 and IL-1β was significantly higher in OSCC patients than controls and dysplasia patients. Univariate fractional polynomial models revealed that salivary IL-8 protein has the highest AUC value between OSCC patients and controls (0.74) and between OSCC and PMOD patients (0.72). Applying a 2-markers fractional polynomial model, salivary IL-8 protein combined with IL-1β gave the best AUC value for discrimination between OSCC patients and controls, as well as the IL-8 protein combined with H3F3A mRNA gave the best AUC value for discrimination between OSCC and PMOD patients. Multivariate models analysis combining salivary analytes and risk factor exposure related to oral carcinogenesis formed the best combinatory variables for differentiation between OSCC vs PMOL (AUC=0.80), OSCC vs controls (AUC=0.87) and PMOD vs. controls (AUC=0.78).

Conclusions

Combination of transcriptomic and proteomic salivary markers is of great value for oral cancer detection and differentiation from PMOD patients and controls.

Keywords: Oral Cavity Carcinoma, Oral Leukoplakia, Saliva, Diagnosis, Biomarkers

Introduction

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is the most common cancer of the head and neck region. High morbidity and mortality is associated with this disease, but little improvement has been observed in the five-years survival rate for patients with OSCC along the years (1). One of the main prognostic factors for OSCC patients is advanced disease (2,3). Considering that, early diagnosis of oral cancer is an important approach to decrease morbidity and mortality rate.

A multi-step carcinogenesis process characterizes OSCC development. Cumulative mutational events occur in the mucosal epithelial stem cells, and the cellular proliferation promotes the expansion of a field of DNA altered cells in the epithelial lining (4–6). Clinical and histopathological signs of altered epithelium can, sometimes, be observed in a form of leukoplakia/erythroplakia (also called potentially malignant oral disorders – PMOD) and cellular dysplasia, respectively (7). Under the effect of new mutational events, malignant transformation can occur in these areas, leading to development of an infiltrative disease (4).

Although the rate of malignant transformation of clinically altered epithelium is low (about 0.13% to 17.5%) (7), detection and close follow up of these lesions are the best approach to early diagnosis of oral cancer. Nowadays, the unique available method for detection of altered epithelium and oral cancer is clinical examination, but it does not allow a reliable differentiation between PMOD and lesions with no risk to cancer progression (8). The rate of detection of early stage oral cancer is low. This can be explained by the asymptomatic characteristic of early stage disease and the lack of an adequate routine mucosal exam by health care practitioners (9,10). The development of a reliable detection method of OSCC and PMOD would be of importance to improve early diagnosis of oral cancer. Consequently, this would favors early treatment, changing survival rates and avoiding the devastating consequences of advanced tumors treatment.

Saliva has been considered an important source of biological information for detection of human diseases. Beyond the obvious relationship with the oral mucosa surface, several studies have demonstrated synergism between expression of molecular markers in saliva and systemic or distant sites diseases. Metabolites, proteins, coding and non-coding RNAs and DNA have been detected in saliva of diseased patients, showing important value in disease detection (11–18).

The role of saliva to detect oral cancer has been studied showing encouraging results (11,13–15,19,20). In 2004 (16), it was determined the salivary transcriptome of oral cancer, showing that it contains a set of promising extracellular RNA (exRNA) markers. These salivary exRNA markers were tested in different OSCC populations showing promising performance for disease detection with sensitivity and specificity higher than 80% (14,19). Inflammatory cytokines also have been investigated as potential biomarkers of oral cancer (13,14,21–23). Hoffman et al. (2007)(21) verified that serum levels of interleukin 8 (IL-8) were significantly higher in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck region when compared with individuals without cancer. Arellano-Garcia et al. (2008)(13) also studied the potential of cytokines to predict cancer, but using saliva as a source of biological information. They observed that IL-8 and IL-1β were significantly more expressed in saliva of OSCC patients than in healthy controls.

Elashoff et al. (2012)(14) demonstrated that the combination of such protein and RNA markers improved the power of predictability of salivary OSCC biomarkers. Although the efficacy of these RNA and protein markers of oral cancer has been demonstrated, race related variations could occur in biomarker discovery. Considering that an ideal biomarker should have a widespread efficacy regardless of ethnicity it is important to challenge these biomarkers in a new population.

Bearing in mind the significance of PMOD in the early diagnosis of OSCC, we decided, for the first time, to test the efficacy of these biomarkers to detection of precursor lesions. The primary objective of this analysis is to assess the discriminatory power of 7 salivary transcriptomic markers (IL-1β, IL-8, SAT1, OAZ1, DUSP1, S100P, H3F3A) and 2 proteomic markers (IL-8, IL-1β) in distinguishing OSCC and PMOD patients from health individuals.

Materials and Methods

Patient selection

Saliva samples were collected, after approval by the Institutional Review Board (#104-2602C), from patients that agreed to sign an informed consent in the Linko Medical Center of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital at Tao-Yuan, Taiwan. A total of 180 samples were included in the dataset, including 60 cases of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC), 60 cases of potentially malignant oral disorders (PMOD) with histopathological evidence of dysplasia and 60 individuals with no clinical sign of malignant or potentially malignant disease in the oral cavity.

Controls were gender and age-matched subjects enrolled during the same period when OSCC subjects were recruited. PMOD and controls received routine physical examination of head and neck regions, and patients with any head and neck disease (exception for PMOD) were excluded. All patients with a history of prior cancer, diabetes, autoimmune disorders, hepatitis, or HIV infection were excluded. Demographical information was obtained by an IRB approved questionnaire. Clinical information of OSCC patients was obtained by pathological report generated after tumor resection. These information are detailed described in Supplementary Table S1.

Saliva collection and processing

Unstimulated saliva was collected and processed separately for RNA and protein according to our published protocol (16). For saliva collection, the donors avoided eating, drinking, smoking, and using oral hygiene products for at least 1 hour before the procedure. The collected samples were centrifuged at 3000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatants were immediately treated with a protease inhibitor mixture (Roche; Cat. No.: 11836145001) and RNase inhibitor (Invitrogen, 10777-019). The samples were aliquoted into smaller volumes and stored at 80°C refrigerator. To avoid protein degradation thawed saliva samples were used once. Saliva was collected at diagnosis for patients with OSCC and PMOD before any surgical procedure. All laboratory measurements of salivary biomarkers were performed at School of Dentistry, Center for Oral/Head & Neck Oncology Research, University of California - Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA - USA.

Primer design

We used a nested PCR approach for measurement of RNA molecules in saliva. Outer primers (OF – outer forward; OR – outer reverse) were designed for cDNA synthesis and pre-amplification. Inner primers (IF – inner forward; IR – inner reverse) were designed for qPCR measurement of the cDNA targets. Primer pairs were designed using the NCBI/Primer-BLAST software. Three genes were used as saliva internal reference: GAPDH, ACTB and RPS9. Only samples that exhibited specific qPCR products for these 3 genes were used in the study. Ct values of all target genes were normalized according to RPS9 gene expression. The target RNAs measured in saliva of the studied individuals were: IL-1β, IL-8, SAT1, OAZ1, DUSP1, S100P, H3F3A. Primers sequences are described in supplementary material (Supplementary Table S2).

Direct saliva transcriptome analysis

A multiplex cDNA synthesis and pre-amplification approach was performed directly in 4μl of saliva for each sample. This technique was developed by our group and is called Direct Saliva Transcriptome Analysis (DSTA) (24). The reactions were performed in 10μl volume with a pool of outer primers at 50μM each and the SuperScript III Taq (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and 2X Reaction Mix. The thermocycler program used is described following: 2 minutes at 60°C, 30 minutes at 50°C, 2 minutes at 95°C, and 15 cycles of 15 seconds at 95°C, 30 seconds at 50°C, 10 seconds at 60°C and 10 seconds at 72°C and cooling at 4°C. The PCR products were treated with 4μl of ExoSAP-IT (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) for 15 minutes at 37°C and then heated to 80°C for 15 minutes.

The target transcripts were quantified from 2μl of pre-amplified cDNA via singleplex qPCR using the Roche LightCycler 480 instrument (Roche, San Francisco, CA). The qPCR reactions were done in a 10μl volume containing 50μM of each inner primer pair and 2X SYBR Green qPCR Mix. The qPCR was carried out under the following conditions: 95°C for 5 minutes and 40 cycles of 10 seconds at 95°C, 10 seconds at 60°C, 10 seconds at 72°C. All of the qPCR reactions were performed in duplicate.

Salivary protein detection

Salivary IL-8 and IL-1β proteins were measured using specific ELISA kits (Thermo Fisher) according to manufacturer’s recommendations. For measurement, saliva samples were diluted in PBS according to recommendation of a previous study (14). For IL-8, saliva was diluted 1:8 and for IL-1β it was diluted 1:3. For interleukin values correction, total salivary protein was measured using Bradford’s method (Bio-Rad) using saliva dilutions of 1:3. All samples were assayed in duplicates using a microplate reader and the results were expressed in picograms per milliliter.

Statistical analysis

Missing values were replaced by the ½ of minimum of the variable. Using the raw data (Supplementary Table S3), nonparametric ANOVA (Kruskal-Wallis Test) was performed to test the overall difference in biomarkers between three groups. If the overall difference is significant, Wilcoxon rank sum test were used to perform two specific comparisons: OSCC vs. controls, OSCC vs. PMOD. Non-parametric tests were used after Shapiro-Wilk test showed that data was not normally distributed. The mRNA markers were normalized subtracting RPS9 gene expression values. Protein markers were normalized dividing its expression levels to total protein values. This was followed by standardization or z-score scaled subtracting the mean and dividing by standard deviation. ROC analysis was performed after running univariate Fractional Polynomial model (FP) (25,26). The marker with highest AUC value was used as the anchor marker. The relationships between the anchor marker and other markers were check by Spearman correlation analysis and visualized by 2-D plots. Whether adding a second marker will increase the discriminatory power of the anchor marker was checked by 2 methods: ROC analysis after running the FP models and logistic regression models. The AUC values and AIC values were compared for different two marker-models. Additionally, multivariate analyses including all salivary markers and risk factors exposure were carried out after running FP and logistic regression models. Statistical analysis was carried out using R version 3.0.2 (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Clinical and demographical data from patients included in this study are described in the Table 1. No difference was observed among groups considering gender and age. Ethanol intake as well as betel nut chewing was higher in OSCC and PMOD patients than in controls. Tobacco use was higher in the PMOD group than among OSCC patients and controls.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of subjects enrolled in the study

| OSCC | PMOD | Controls | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects | % | Subjects | % | Subjects | % | p | ||

| Gender | Male | 57 | 95 | 57 | 95 | 55 | 91.7 | 0.678 |

| Female | 3 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 8.3 | ||

| Age | < 39 | 6 | 10 | 12 | 20 | 18 | 30 | 0.923 |

| 40 – 49 | 21 | 35 | 15 | 25 | 11 | 18.3 | ||

| 50 – 59 | 23 | 38.3 | 21 | 35 | 14 | 23.3 | ||

| 60 – 69 | 7 | 11.7 | 9 | 15 | 10 | 16.7 | ||

| > 70 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 11.7 | ||

| Ethanol consumption | Yes | 41 | 68.33 | 38 | 63.3 | 25 | 41.7 | 0.007 |

| No | 19 | 31.67 | 22 | 36.7 | 35 | 58.3 | ||

| Betel nut chewing | Yes | 52 | 86.67 | 48 | 80 | 28 | 46.7 | < 0.001 |

| No | 8 | 13.33 | 12 | 20 | 32 | 53.3 | ||

| Tobacco consumption | Yes | 50 | 83.33 | 58 | 96.7 | 49 | 81.7 | 0.02 |

| No | 10 | 16.67 | 2 | 3.3 | 11 | 18.3 | ||

| Tumor size | T1 | 20 | 33.33 | - | - | - | - | - |

| T2 | 19 | 31.67 | - | - | - | - | ||

| T3 | 5 | 8.33 | - | - | - | - | ||

| T4a | 14 | 23.33 | - | - | - | - | ||

| T4b | 2 | 3.33 | - | - | - | - | ||

| Lymph node status | N0 | 34 | 56.67 | - | - | - | - | - |

| N1 | 8 | 13.33 | - | - | - | - | ||

| N2a | 1 | 1.67 | - | - | - | - | ||

| N2b | 15 | 25 | - | - | - | - | ||

| N2c | 2 | 3.33 | - | - | - | - | ||

| Distant metastasis | M0 | 60 | 100 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Clinical Stage | I | 18 | 30 | - | - | - | - | - |

| II | 10 | 16.67 | - | - | - | - | ||

| III | 6 | 10 | - | - | - | - | ||

| IVa | 24 | 40 | - | - | - | - | ||

| IVb | 2 | 3.33 | - | - | - | - | ||

ANOVA test;

The expression values for the analyzed salivary mRNAs and proteins are described in the Table 2. Significant differences were observed in the expression level of DUSP1 between OSCC patients and controls (p-value = 0.0123) as well as between OSCC patients and PMOD patients (p-value= 0.0422). The concentration of IL-8 protein (IL-8p) was significantly higher in OSCC patients when compared to controls (p-value < 0.0001) and PMOD patients (p-value < 0.0001) (Figure 1a). Similarly, salivary IL-1βprotein (IL-1βp) concentration was significantly higher in OSCC patients than in controls (p-value < 0.01) and PMOD patients (p-value 0.004).

Table 2.

Expression values for salivary mRNAs and proteins according to the studied groups

| OSCC patients | Controls | PMOD patients | Kruskal- Wallis Test | Wilcoxon Two-Sample Test | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | SD | Min | Max | Mean | SD | Min | Max | Mean | SD | Min | Max | p-value | p-value OSCC vs. Control | p-value OSCC vs. PMOD |

| IL-1β | 28.80 | 4.63 | 21.10 | 41.00 | 27.57 | 4.29 | 20.80 | 41.00 | 28.73 | 4.70 | 21.20 | 41.00 | 0.28 | ||

| IL-8 | 27.34 | 3.88 | 20.10 | 38.40 | 27.19 | 3.97 | 20.40 | 41.00 | 28.09 | 4.35 | 20.70 | 41.00 | 0.50 | ||

| SAT1 | 27.87 | 3.23 | 21.10 | 36.90 | 27.55 | 3.65 | 21.20 | 38.3 | 27.97 | 2.92 | 21.40 | 35.00 | 0.61 | ||

| OAZ1 | 23.77 | 3.71 | 15.90 | 32.30 | 24.15 | 3.92 | 17.80 | 33.30 | 24.11 | 3.94 | 17.30 | 33.10 | 0.96 | ||

| DUSP1 | 34.99 | 5.91 | 22.60 | 41.00 | 32.36 | 6.10 | 23.40 | 41.00 | 32.81 | 5.95 | 23.10 | 41.00 | 0.03 | 0.0123 | 0.0422 |

| S100P | 35.38 | 4.44 | 25.70 | 41.00 | 34.19 | 4.49 | 25.50 | 41.00 | 35.66 | 4.30 | 25.00 | 41.00 | 0.19 | ||

| H3F3A | 20.60 | 4.21 | 12.20 | 33.30 | 21.00 | 4.76 | 13.80 | 33.00 | 20.60 | 3.85 | 13.00 | 32.90 | 0.99 | ||

| GAPDH | 17.56 | 3.45 | 9.80 | 28.10 | 17.64 | 3.20 | 11.70 | 26.90 | 18.11 | 3.40 | 11.50 | 28.50 | 0.60 | ||

| ACTB | 23.02 | 3.77 | 13.50 | 32.70 | 23.25 | 3.79 | 16.50 | 32.70 | 23.64 | 4.26 | 15.40 | 34.70 | 0.88 | ||

| RPS9 | 22.62 | 3.87 | 15.30 | 33.00 | 23.10 | 3.66 | 15.20 | 31.90 | 23.77 | 4.10 | 17.30 | 36.20 | 0.40 | ||

| IL-8_pg/ml | 283.75 | 262.33 | 0.00 | 1048.72 | 127.79 | 110.84 | 0.00 | 654.89 | 140.35 | 155.13 | 0.00 | 1048.72 | <.0001* | <.0001* | <.0001* |

| IL-1β_pg/ml | 101.03 | 112.96 | 0.00 | 419.49 | 48.07 | 42.01 | 0.00 | 161.99 | 39.66 | 28.00 | 1.61 | 145.83 | 0.0061* | 0.01* | 0.004* |

| Total_protein_mg/ml | 1.21 | 0.64 | 0.07 | 2.94 | 1.08 | 0.52 | 0.17 | 2.61 | 0.96 | 0.44 | 0.28 | 2.14 | 0.11 | ||

: p-values obtained from comparisons after normalization to total protein and standardization

Fig. 1.

a) Salivary expression of IL-8 protein among the studied groups. IL-8 expression was significantly higher in cancer patients compared to controls and PMOD patients. Whiskers represent median. b) ROC curves for salivary IL-8 protein. The AUC value for cancer patients distinguishing from controls and PMOD patients was 0.749 and 0.721, respectively. c) ROC curves for combination of salivary IL-8 protein and IL-1β mRNA. The AUC value for cancer patients distinguishing from controls and PMOD patients was 0.81 and 0.73, respectively. d) 2D scatterplot showing the correlation between the expression of salivary IL-8 protein and IL-1 β mRNA in controls and oral cancer patients. e) ROC curves for combination of salivary IL-8 protein and H3F3A mRNA. The AUC value for cancer patients distinguishing from controls and PMOD patients was 0.75 and 0.75, respectively. f) 2D scatterplot showing the correlation between the expression of salivary IL-8 protein and H3F3A mRNA in controls and oral cancer patients. g) ROC curves generated by multivariate fractional polynomial analysis using three different combinations of variables. Blue line: IL-1β + Areca Nut + Drinking + Smoking for differentiation between PMOD and controls (AUC = 0.802). Red line: DUSP1 + IL-1βp + IL-8p + Areca Nut for differentiation between OSCC and controls (AUC = 0.872). Green line: H3F3A + IL-8p + Smoking for differentiation between OSCC and PMOD (AUC = 0.785). h) ROC curves generated by logistic regression models using three different combinations of variables. Blue line: IL-1β + Areca Nut + Drinking + Smoking for differentiation between PMOD and controls (AUC = 0.716). Red line: DUSP1 + IL-1βp + IL-8p + Areca Nut for differentiation between OSCC and controls (AUC = 0.810). Green line: H3F3A + IL-8p + Smoking for differentiation between OSCC and PMOD (AUC = 0.771).

Using univariate fractional polynomial models, the IL-8p gave the highest AUC (AUC= 0.749) in distinguishing OSCC patients from controls after running the model on each biomarker. The univariate model with IL-8p as predictor also had the lowest AIC (AIC=150.99). Similarly, the protein marker IL-8p gave a highest AUC (AUC= 0.721) and the lowest AIC (AIC=150.88) in distinguishing OSCC from PMOD group (Table 3) (Figure 1b).

Table 3.

ROC analysis using univariate fractional polynomial model of salivary transcriptomic and proteomic markers and risk factors exposure

| Univariate model | PMOD vs. Controls | OSCC vs. controls | OSCC vs. PMOD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | AUC | AIC | AUC | AIC | AUC | AIC |

| IL-8 | 0.467 | 166.58 | 0.449 | 166.33 | 0.518 | 170.13 |

| IL-1β | 0.542 | 170.11 | 0.721 | 151.49 | 0.569 | 168.63 |

| OAZ1 | 0.508 | 170.32 | 0.519 | 170.33 | 0.576 | 168.07 |

| SAT1 | 0.483 | 170.23 | 0.643 | 162 | 0.563 | 168.52 |

| DUSP1 | 0.563 | 168.77 | 0.649 | 162.8 | 0.651 | 162.24 |

| S100P | 0.552 | 169.59 | 0.597 | 167.17 | 0.542 | 169.48 |

| H3F3A | 0.564 | 166.6 | 0.524 | 170.33 | 0.589 | 165.18 |

| IL-1βp | 0.646 | 159.09 | 0.637 | 159.71 | 0.655 | 156.75 |

| IL-8p | 0.498 | 170.16 | 0.749 | 150.99 | 0.721 | 150.88 |

| Total protein | 0.568 | 168.72 | 0.551 | 166.06 | 0.607 | 164.39 |

| Smoking | 0.575 | 162.74 | 0.515 | 168.76 | 0.56 | 163.56 |

| Drinking | 0.608 | 164.66 | 0.639 | 159.5 | 0.531 | 168.45 |

| Areca nut | 0.667 | 155.6 | 0.707 | 144.3 | 0.541 | 167.48 |

Using the salivary expression of IL-8p as an anchor marker and applying the 2-marker fractional polynomial models, the combination of IL-8p and IL-1β gave the highest AUC (AUC= 0.817) in distinguishing OSCC patients from controls. This two-marker model also had the lowest AIC (AIC=138.28) (Figure 1c and 1d). When the sensitivity of the test was fixed at 0.9 in distinguishing OSCC patients from controls this two-marker model gave the highest maximized specificity (MaxSpec = 0.56). In contrast, the combination of IL-8p and H3F3A gave a highest AUC (AUC= 0.752) and the lowest AIC (AIC=141.34) in distinguishing OSCC patients from PMOD patients (Table 4) (Figure 1e and 1f). When the sensitivity of the test was fixed at 0.9 in distinguishing OSCC patients from PMOD patients, this 2-makers model gave the highest maximized specificity (MaxSpec = 0.45).

Table 4.

ROC analysis of 2-marker fractional polynomial model using the salivary expression of IL-8 protein as an anchor marker

| OSCC vs. controls | OSCC vs. PMOD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two markers model | AUC | AIC | AUC | AIC |

| IL-8p + IL-1β | 0.817 | 138.28 | 0.739 | 150.7 |

| IL-8p + OAZ1 | 0.751 | 152.97 | 0.734 | 148.76 |

| IL-8p + SAT1 | 0.794 | 145.06 | 0.738 | 150.98 |

| IL-8p + DUSP1 | 0.754 | 148.62 | 0.726 | 153.75 |

| IL-8p + S100P | 0.767 | 150.54 | 0.723 | 152.16 |

| IL-8p + H3F3A | 0.75 | 152.86 | 0.752 | 141.34 |

| IL-8p + IL-1βp | 0.74 | 152.67 | 0.685 | 155.25 |

Multivariate models analysis considering expression of salivary biomarkers and risk factor exposure were carried out using the fractional polynomial model and the logistic model (Table 5). Using the same marker combination, fractional polynomial model gave the highest AUC and the lowest AIC values when compared to logistic model (Figure 1g and 1h). Areca nut chewing, drinking and smoking habits associated to salivary expression of IL-1β transcript was the best variable combination for distinction between PMOD patients and controls (AUC = 0.785). When sensitivity was fixed at 0.9 the MaxSpec obtained was 0.9. Areca nut chewing associated to salivary expression of DUSP1 transcript, IL-1βp and IL-8p revealed the best combinatory effect for differentiation between OSCC patients and controls (AUC = 0.872). Fixing sensitivity at 90% MaxSpec obtained was 0.63. For separation between OSCC and PMOD patients, smoking associated to salivary H3F3A transcript and IL-8p expression showed up as the best combinatory makers (AUC=0.802). When sensitivity was set at 0.9 MaxSpec obtained was 0.53.

Table 5.

Multivariate model ROC analyses of the optimal models using FP and logistic models

| PMOD vs. Controls | OSCC vs. Controls | OSCC vs. PMOD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | IL-1β + ArecaNut + Drinking + Smoking | DUSP1 + IL-1βp + IL-8p + ArecaNut | H3F3A + IL-8p + Smoking | |

| Fractional polynomial model | AUC | 0.785 | 0.872 | 0.802 |

| AIC | 145.59 | 120.16 | 135.32 | |

| Logistic model | AUC | 0.716 | 0.81 | 0.771 |

| AIC | 156.32 | 137.28 | 146.07 |

Discussion

South and Central Asia has one of the highest incidences and mortality rates of OSCC in the world. The consumption of areca nut (betel) associated or not with tobacco is the main risk factor for OSCC development among these people. Taiwan has one of the highest consumptions of areca nut, explaining why this country has one of the biggest prevalence of PMOD in the world (12.7%) and a high incidence rate of oral cancer (27,28).

Areca nut usage is an important cause of PMOD, as well as tobacco. However, beyond the development of leukoplakia and erythroplakia, it can also induce a very distinct form of PMOD called oral submucous fibrosis (OSF) (28,29). OSF is more prevalent among Southeast Asians, being rare in the western countries. This may indicate that the pathways involved in the oral cancer development among Southeast Asians might diverge from occidental patients. However, even with these ethnic and behavior variations, the biomarkers developed in the western population and applied in this study showed a good performance for discrimination between oral cancer and controls in Taiwanese individuals, revealing high AUC values and high sensitivity. These biomarkers were challenged before in different populations from USA and Serbia, in which tobacco and alcohol consumption are the main etiological factor for OSCC (14,19). In these studies the performance of the biomarkers were similar from those observed in the present manuscript.

In this study, the proteomic markers had better performance than transcriptomic markers in distinguishing oral cancer cases from PMOD and controls when considered individually. The salivary IL-8 protein alone model performed best among the univariate models, always giving the highest AUC values than other individual marker. In other validation studies in western populations, IL-8 and IL-1β proteins were also potential salivary biomarkers for oral cancer detection, showing sensitivity and specificity ranging from 70% to 80% and an AUC value around 0.7 (14,19). Although salivary IL-1β protein was not considered a good marker for OSCC detection in our investigation, IL-8 showed AUC value (0.73) similar to other studies, confirming the reproducibility of this marker across different oral cancer populations.

However, as observed by others (14,16,19), the combination of proteomic and transcriptomic markers revealed the best discriminatory effect between oral cancer and non-cancer individuals. According to Li et al. (16), salivary IL-8, IL-1β, SAT and OAZ1 mRNA detection formed the best combinatory markers for OSCC detection. Elashoff et al. (14) tested these biomarkers in 5 cohorts of patients and controls. They observed that for some of the cohorts the combination of biomarkers with the best performance for oral cancer diagnosis would change, giving AUC values varying from 0.75 to 0.86. However, the IL-8 and SAT mRNAs were present in all the 5 different combinations, suggesting that these biomarkers are the most consistent ones. For Brinkmann et al. (19) the best discriminatory markers for OSCC detection was the combination of IL-1β protein and the SAT1 and DUSP1 mRNAs revealing an AUC value of 0.86. In our study, we obtained an AUC of 0.817 that is in the range of AUC values obtained in previous studies, but using just two markers, IL-8 protein combined to IL-1β mRNA.

Beyond univariate and two-marker analysis we carried out a multivariate analysis including all possible combination of salivary analytes and also considering exposure to risk factors related to OSCC and PMOD development. Combining these parameters we were able to generate a set of predictors of great value for disease detection. The distinction between OSCC and controls as well as OSCC and PMOD was greatly dependent on risk factor exposure status. Using such information we observed a significant increase in test accuracy, achieving an AUC of 0.87 for differentiation between OSCC and controls and 0.80 for differentiation between OSCC and PMOD individuals.

One of the most important approaches for improve survival and decrease morbidity in oral cancer patients is the detection of early stage cancer. Detection of PMOD is of extreme importance, but its discrimination from early stage oral cancer can be challenging. Currently, the most efficient available method of diagnosis of these potentially malignant lesions and discrimination from oral cancer is biopsy followed by histopathological examination. Beyond the need of highly trained personal to do such exams, it is costly, time consuming and is associated with patient distress and risk since it is a surgical intervention. The development of a salivary biomarker with potential of discriminatory diagnosis between these two entities would be of great value. In this present study we showed, for the first time, that salivary biomarkers have discriminatory effect for discrimination between malignant and PMOD. High expression of IL-1β transcript associated to consumption of betel, alcohol and tobacco generated the highest AUC value for differentiation between PMOD and controls. Importantly, for this combination of parameters we obtained specificity and sensibility of 90%, indicating a high accuracy test for detection of PMOD. This finding is of great importance for screening purposes in populations exposed to these risk factors, since the measurement of just one salivary biomarker would give a very accurate indication of PMOD diagnosis.

For some of our analysis, setting high sensitivity values (90%) lead to low maximum specificity. This occurred for differentiation between OSCC and controls and OSCC and PMOL. Although low specificity represents a limitation of the proposed biomarker combination, we believe that for a screening approach, high sensitivity is the most important parameter, since it provides a low number of false negative cases and select candidate cases for complementary clinical evaluation.

Another potential limitation of our findings is the lack of periodontal evaluation of studied cases. Inflammatory diseases such as periodontitis are one of the most common pathologies in oral cavity, representing the most common inflammatory disease in humans (30,31). Considering that some of our candidate biomarkers are cytokines (IL-8 and IL-1β), one may suggest that inflammatory diseases in oral cavity may represent a confusion factor in our analysis. Furthermore OSCC, PMOD and periodontitis share the same etiological factors, such as tobacco (32,33). However, Cheng et al. (2014) (34) compared the salivary IL-8 protein expression between OSCC patients and patients with periodontitis. They observed that IL-8 salivary levels were significantly higher in OSCC when compared to chronic periodontitis patients (p<0.001) and healthy controls (p=0.014). Also, mean expression in chronic periodontitis patients was lower (0.58±0.26 pg/mL) than in healthy controls (0.80±0.41 pg/mL). This may indicate that inflammatory conditions may have little effect on our results. Moreover, inflammatory reaction elicited in periodontitis and in OSCC is of different nature, since microbes are the main players in the induction of the former (34).

An important aspect of this work is the use of direct saliva transcriptome analysis (DSTA) technique that allows the measurement of salivary transcripts directly from saliva with no need of RNA extraction prior analysis (24). This approach is of utmost importance for implementation of such biomarkers in a clinical practice. RNA extraction is involved with higher costs, need of trained personal, and is time consuming. In this work we demonstrated that salivary RNA and protein could be measured directly from saliva, with no need of prior treatment. We believe that in the near future these biomarkers could be measured using portable technologies permitting its use in an ambulatory environment (27).

We concluded that proteomic and transcriptomic salivary biomarkers are of great value for oral cancer and PMOD detection in Taiwanese population. Salivary analytes and status of risk factors exposure related to oral carcinogenesis emerged as the best combination of variables for OSCC and PMOL detection. Also, for the first time, we demonstrated that the salivary analytes have discriminatory power for PMOD diagnosis, representing a potential tool for early detection of patients in risk of oral cancer development.

Supplementary Material

Statement of translational relevance.

Early diagnosis is a need to decrease morbidity and increase survival of oral squamous cell carcinoma patients. Salivary diagnostics is emerging as an important tool for human cancer detection. In our study, we showed that salivary biomarkers are useful for oral squamous cell carcinoma diagnosis in a Taiwanese population. Considering previous published results, we can infer that these salivary biomarkers are useful for oral cancer detection regardless ethnicity. Our results support the idea that salivary diagnostics might be used in the clinical practice for oral squamous cell carcinoma detection and works as a differential diagnosis test with other oral potentially malignant disorders. In this way, it permits that large-scale screening tests are implemented for oral cancer and potentially malignant disorders detection in high incident areas.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This study was supported by NIDCR/NIH research grants R01 DE17170 and NIH/UH2 TR000923 to D.T.W. Wong; MOST 102-2628-B-182A-012-MY3 from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan, to Kai-Ping Chang. Frederico Omar Gleber-Netto was supported by the grants 2011/13315-4 and 2013/09142-2 from São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: David Wong is co-founder of RNAmeTRIX Inc., a molecular diagnostic company. He holds equity in RNAmeTRIX, and serves as a company Director and Scientific Advisor. The University of California also holds equity in RNAmeTRIX. Intellectual property that David Wong invented and which was patented by the University of California has been licensed to RNAmeTRIX. Additionally, he is a consultant to PeriRx, GlaxoSmithKlein and Wrigley

References

- 1.Carvalho AL, Nishimoto IN, Califano Ja, Kowalski LP. Trends in incidence and prognosis for head and neck cancer in the United States: a site-specific analysis of the SEER database. Int J Cancer. 2005;114:806–16. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Harten MC, de Ridder M, Hamming-Vrieze O, Smeele LE, Balm AJM, van den Brekel MWM. The association of treatment delay and prognosis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) patients in a Dutch comprehensive cancer center. Oral Oncol. 2014;50:282–90. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2013.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts Fig. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2012. Cancer Facts & Figures; p. 68. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Califano J, van der Riet P, Westra W, Nawroz H, Clayman G, Piantadosi S, et al. Genetic progression model for head and neck cancer: implications for field cancerization. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2488–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leemans CR, Braakhuis BJM, Brakenhoff RH. The molecular biology of head and neck cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:9–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc2982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braakhuis BJM, Tabor MP, Kummer JA, Leemans CR, Brakenhoff RH. A genetic explanation of Slaughter’s concept of field cancerization: evidence and clinical implications. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1727–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Napier SS, Speight PM. Natural history of potentially malignant oral lesions and conditions: an overview of the literature. J Oral Pathol Med. 2008;37:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moyer VA. Screening for oral cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:55–60. doi: 10.7326/M13-2568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neville BW, Day Ta. Oral Cancer and Precancerous Lesions. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002;52:195–215. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.52.4.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McGurk M, Chan C, Jones J, O’regan E, Sherriff M. Delay in diagnosis and its effect on outcome in head and neck cancer. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;43:281–4. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2004.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park NJ, Zhou H, Elashoff D, Henson BS, Kastratovic Da, Abemayor E, et al. Salivary microRNA: discovery, characterization, and clinical utility for oral cancer detection. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5473–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wei F, Lin C-C, Joon A, Feng Z, Troche G, Lira ME, et al. Non-Invasive Saliva-Based EGFR Gene Mutation Detection in Lung Cancer Patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014:1–52. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201406-1003OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arellano-Garcia ME, Hu S, Wang J, Henson B, Zhou H, Chia D, et al. Multiplexed immunobead-based assay for detection of oral cancer protein biomarkers in saliva. Oral Dis. 2008;14:705–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2008.01488.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elashoff D, Zhou H, Reiss J, Wang J, Xiao H, Henson B, et al. Prevalidation of salivary biomarkers for oral cancer detection. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:664–72. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagler RM. Saliva as a tool for oral cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:1006–10. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y, John M, Zhou X, Kim Y. Salivary transcriptome diagnostics for oral cancer detection. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:8442–50. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernardes VF, Gleber-Netto FO, Sousa SF, Silva TA, Abreu MHNG, Aguiar MCF. EGF in saliva and tumor samples of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2011;19:528–33. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0b013e3182143367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim JK, Zhou H, Nabili V, Wang MB, Abemayor E, Wong DTW. Utility of multiple sampling in reducing variation of salivary interleukin-8 and interleukin-1β mRNA levels in healthy adults. Head Neck. 2013;35:968–73. doi: 10.1002/hed.23063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brinkmann O, Kastratovic Da, Dimitrijevic MV, Konstantinovic VS, Jelovac DB, Antic J, et al. Oral squamous cell carcinoma detection by salivary biomarkers in a Serbian population. Oral Oncol. 2011;47:51–5. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng Y-SL, Rees T, Jordan L, Oxford L, O’Brien J, Chen H-S, et al. Salivary endothelin-1 potential for detecting oral cancer in patients with oral lichen planus or oral cancer in remission. Oral Oncol. 2011;47:1122–6. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoffmann T, Sonkoly E. Aberrant cytokine expression in serum of patients with adenoid cystic carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 2007;29:472–8. doi: 10.1002/hed.20533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Korostoff A, Reder L, Masood R, Sinha UK. The role of salivary cytokine biomarkers in tongue cancer invasion and mortality. Oral Oncol. 2011;47:282–7. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Punyani SR, Sathawane RS. Salivary level of interleukin-8 in oral precancer and oral squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Oral Investig. 2013;17:517–24. doi: 10.1007/s00784-012-0723-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee YH, Zhou H, Reiss JK, Yan X, Zhang L, Chia D, et al. Direct saliva transcriptome analysis. Clin Chem. 2011;57:1295–302. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.159210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Royston P, Altman DG. Regression Using Fractional Polynomials of Continuous Covariates: Parsimonious Parametric Modelling. Appl Stat. 1994;43:429. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sauerbrei W, Meier-Hirmer C, Benner A, Royston P. Multivariable regression model building by using fractional polynomials: Description of SAS, STATA and R programs. Comput Stat Data Anal. 2006;50:3464–85. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Warnakulasuriya S. Global epidemiology of oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:309–16. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson NW, Jayasekara P, Amarasinghe aaHK. Squamous cell carcinoma and precursor lesions of the oral cavity: epidemiology and aetiology. Periodontol 2000. 2011;57:19–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2011.00401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee C-H, Ko Y-C, Huang H-L, Chao Y-Y, Tsai C-C, Shieh T-Y, et al. The precancer risk of betel quid chewing, tobacco use and alcohol consumption in oral leukoplakia and oral submucous fibrosis in southern Taiwan. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:366–72. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chapple ILC. Time to take periodontitis seriously. BMJ. 2014;348:g2645–g2645. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Batchelor P. Is periodontal disease a public health problem? Br Dent J. 2014;217:405–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dye B. Global periodontal disease epidemiology. Periodontol 2000. 2012;58:10–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2011.00413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petersen P, Ogawa H. The global burden of periodontal disease: towards integration with chronic disease prevention and control. Periodontol 2000. 2012;60:15–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2011.00425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lisa Cheng Y-S, Jordan L, Gorugantula LM, Schneiderman E, Chen H-S, Rees T. Salivary interleukin-6 and -8 in patients with oral cancer and patients with chronic oral inflammatory diseases. J Periodontol. 2014;85:956–65. doi: 10.1902/jop.2013.130320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.