Abstract

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) is a ligand-activated transcription factor within the Per-Arnt-Sim (PAS) domain superfamily. Exposure to the most potent AHR ligand, 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD), is associated with various pathological effects including metabolic syndrome. While research over the last several years has demonstrated a role for oxidative stress and metabolic dysfunction in AHR-dependent TCDD-induced toxicity, the role of the mitochondria in this process has not been fully explored. Our previous research suggested that a portion of the cellular pool of AHR could be found in the mitochondria (mitoAHR). Using a protease protection assay with digitonin extraction, we have now shown that this mitoAHR is localized to the inter-membrane space (IMS) of the organelle. TCDD exposure induced a degradation of mitoAHR similar to that of cytosolic AHR. Furthermore, siRNA-mediated knockdown revealed that translocase of outer-mitochondrial membrane 20 (TOMM20) was involved in the import of AHR into the mitochondria. In addition, TCDD altered cellular respiration in an AHR-dependent manner to maintain respiratory efficiency as measured by oxygen consumption rate (OCR). Stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) identified a battery of proteins within the mitochondrial proteome influenced by TCDD in an AHR-dependent manner. Among these, 17 proteins with |fold changes| ≥ 2 are associated with various metabolic pathways, suggesting a role of mitochondrial retrograde signaling in TCDD-mediated pathologies. Collectively, these studies suggest that mitoAHR is localized to the IMS and AHR-dependent TCDD-induced toxicity, including metabolic dysfunction, wasting syndrome, and hepatic steatosis, involves mitochondrial dysfunction.

Keywords: Aryl hydrocarbon receptor; mitochondria; oxidative phosphorylation; proteomics; SILAC; 2,3,7,8- tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin; TCDD

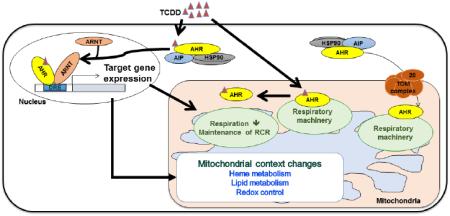

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR), one of the PAS domain family members, is a ligand-activated transcription factor that mediates the toxic response to several prominent environmental pollutants, such as halogenated aromatic hydrocarbons and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (McIntosh et al., 2010). Among these toxicants, 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) is the most potent AHR ligand (Mandal, 2005). TCDD exposure alters multiple signaling pathways in a species- and tissue-specific manner, showing various deleterious physiological effects such as tumor promotion, endocrine disruption, chloracne, wasting syndrome, and hepatic steatosis (Mandal, 2005). In the absence of a ligand, the AHR resides in cytoplasm in complex with a homodimer of the heat shock protein of 90 kDa (HSP90) and an immunophilin-like protein called the AHR-interacting protein (AIP, also known as ARA9, or XAP2) (Carver et al., 1998; Heid et al., 2000; LaPres et al., 2000). In the presence of a ligand, the AHR is translocated to the nucleus and forms a heterodimer with the AHR nuclear translocator (ARNT). The AHR:ARNT heterodimer acts as a functional transcription factor by binding to a specific nucleotide sequence, called a dioxin-responsive element or xenobiotic-responsive element, in regulatory regions of DNA and alters target gene expression (e.g., cytochrome P450 monooxygenases, UDP-glucuronosyltransferases, glutathione S-transferases, and TCDD-inducible poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase) (McIntosh et al., 2010).

As many drug-metabolizing and detoxification enzymes induced by TCDD are linked to reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, oxidative stress is commonly associated with TCDD exposures (Kennedy et al., 2013; Lu et al., 2011; Shen et al., 2005; Shertzer et al., 2006). Mitochondria play an important role in TCDD-induced oxidative stress. TCDD exposure causes AHR-dependent mitochondrial ROS production, a shift in thiol redox state between cytosol and mitochondria, suppression of mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) activities, and mitochondrial membrane hyperpolarization in hepatocytes (Aly and Domenech, 2009; Bansal et al., 2014; Senft et al., 2002a; Senft et al., 2002b; Shen et al., 2005). In addition, the AHR has been linked to mitochondria-to-nucleus stress signaling (Biswas et al., 2008). Moreover, the AHR can induce changes in metabolic flux, independent of transcription (Tappenden et al., 2011). Given that mitochondria are critical components of cellular metabolism, the main sites for energy production, and that many pathophysiological effects linked to TCDD exposure (e.g. diabetes, wasting syndrome, hepatic steatosis, and embryonic development) are related to metabolic pathways, researchers have focused on mitochondrial dysfunction as a potential player in TCDD-induced toxicity (Aly and Domenech, 2009; Angrish et al., 2011; Carreira et al., 2015; Diani-Moore et al., 2010; Diani-Moore et al., 2013; Forgacs et al., 2010; Forgacs et al., 2013).

Recently, high-throughput proteomic analysis uncovered an interaction between the AHR and ATP5α1, an ATP synthase subunit, and MRPL40, a mitochondrial ribosomal protein. Interestingly, these interactions were lost upon exposure to TCDD (Tappenden et al., 2013; Tappenden et al., 2011). In addition, the cytosolic binding partners of the AHR (i.e., AIP and HSP90) can bind the mitochondrial translocase of outer-membrane complex, and facilitate mitochondrial import of proteins lacking classic mitochondrial targeting sequences (MTS), such as the AHR. Therefore, we investigated the putative mitochondrial localization of the AHR (mitoAHR) and AHR-mediated TCDD-induced mitochondrial changes. Here, we demonstrate that TOMM20 is important for mitochondrial import of mitoAHR and that mitochondrial function is negatively impacted by TCDD exposure in an AHR-dependent manner. Furthermore, using stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC), we identified a battery of mitochondrial proteins whose expression was influenced by TCDD in an AHR-dependent manner.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture

The mouse hepatoma cell line, hepa1c1c7, were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) with L-glutamine (#11965, Gibco, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% cosmic calf serum (Hyclone, GE, Logan, UT), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (#11360, Gibco), 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (#15140, Gibco). The mouse hepatoma cell line, hepac12, were grown in DMEM with L-glutamine (#11965, Gibco) supplemented with 10% cosmic calf serum (Hyclone) and 1 mM sodium pyruvate (#11360, Gibco). All cell culture work was performed under standard cell culture conditions (5% CO2, 35% humidity and 37 °C) in a NAPCO 7000 incubator (NAPCO, Winchester, VA) unless specified.

Preparation of Intracellular Fractions

Nuclear, cytosolic, and mitochondrial fractions were isolated using protocols adapted from previous reports (Frezza et al., 2007; Vengellur and LaPres, 2004; Yang et al., 2009). Cells were washed with cold PBS (4 °C) and removed from the plate surface by being scraped in mitochondrial buffer A (250 mM sucrose, 20 mM HEPES, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 1 mM ethylene glycol-bis(2-aminoethylether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA), 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF)). Each sample was then homogenized with 100 strokes in a Dounce homogenizer on ice. A 50 μL aliquot was saved and represents a whole cell lysate. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation (400 × g for 10 min at 4 °C) and the pellet was collected for further preparation of a nuclear fraction (see below). The supernatant was cleared by centrifugation (10,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C). The subsequent supernatant was collected as a cytosolic fraction and the pellet was resuspended in mitochondrial buffer A for further preparation of mitochondrial fraction. The resuspended pellet was centrifuged to remove insoluble material (400 × g for 10 min at 4 °C). The supernatant was further cleared by centrifugation (10,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C) and aspirated and the mitochondrial pellet was obtained for further analysis. The nuclear pellet was suspended with nuclear extraction buffer [20 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 1.5 mM magnesium chloride (MgCl2), 420 mM KCl, 20% glycerol, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, and 0.4 mM PMSF and Complete-mini EDTA-free protease inhibitor (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN)], incubated for 30 min at 4 °C, and, then, cleared by centrifugation (17,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C). The supernatant was collected and represents the nuclear fraction. Each intracellular fraction was stored at −80 °C until appropriate assays were performed.

siRNA Knockdown of AIP or TOMM20

When cells were 50% confluent, the siRNAs specific for AIP (Ambion s62179 (siAIP1), s62181 (siAIP2), Life Technologies), and the Silencer® Select Negative Control no. 1 siRNA (Ambion) were transfected into hepa1c1c7 cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's protocol. For TOMM20 knockdown, the siRNA for TOMM20 (Tomm20 ON-TARGET plus, SMARTpool L-006487-01-0005, Dharmacon, GE) and the nontargeting siRNA (Dharmacon, GE) were transfected into hepa1c1c7 cells. After a 72 h incubation, cells were washed three times in cold (4 °C) phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and harvested with 1 mL of mitochondrial buffer A per 15 cm plate. Cells were stored at −80 °C until purification of the nuclear, cytosolic, and mitochondrial fraction was performed.

Protein Concentration Determination

Protein concentrations for samples used for the SILAC experiments were determined using Pierce™ BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Protein concentrations for samples used for all other experiments were determined using Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA) Bradford assay kit and bovine serum albumin (BSA) standards (Lowry et al., 1951).

Trypsin Treatment of Digitonin Extracted Mitochondria

Protease protection in combination with digitonin extraction of mitochondria was adapted from a previous report (Griparic and van der Bliek, 2005). Briefly, purified mitochondria were washed with mitochondrial buffer A without dithiothreitol and PMSF and diluted to 1 μg/μL. Mitochondrial samples (400 μg) were then treated with trypsin (100 μg/mL) in the presence and absence of varying concentrations of digitonin (final concentration = 0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0 mg digitonin/mg protein). Samples were rotated at 4 °C for 30 min and digestion was stopped with the addition of cold 20% trichloroacetic acid to a final concentration of 5%. After vortexing, samples were incubated at 65 °C for 5 min and placed on ice for 1 h. Samples were pelleted by centrifugation (17,000 × g for 10 min) and washed with 1 mL of cold acetone. After centrifugation at 17,000 × g for 5 min, pellets were dried on ice for 10 min and dissolved in 80 μL of 1X Laemmli sample buffer. 1 μL of unbuffered 1 M Tris was added to adjust sample pH and 35 μL of each sample was loaded on 4–12% NuPAGE gel (Invitrogen, Life Technologies) for Western blot analysis.

Western Blotting

Equal amounts of protein from each sample was separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The nitrocellulose membrane was probed with one of the following antibodies: rabbit polyclonal anti-AHR BEAR3 (generous gift from Dr. Christopher Bradfield, University of Wisconsin-Madison) for the samples from AIP and TOMM20 knockdown, HSP90 inhibition and digitonin/trypsin treatment to hepa1c1c7 cells, rabbit anti-AHR (BML-SA210, Enzo Life Sciences Inc., Farmingdale, NY) for digitonin/trypsin treatment to hepa1c1c7 cells exposed to TCDD, goat polyclonal anti-AIP (#115588, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), rabbit polyclonal anti-lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (a generous gift from Dr. John Wang, Michigan State University), rabbit anti-histone H3 (ab1791, Abcam), mouse monoclonal anti-ATP5α (ab14748, Abcam), rabbit polyclonal anti-HSP90 (ab19021, Abcam), mouse monoclonal anti-cytochrome c oxidase subunit IV (COX4) (A21348, Invitrogen), mouse monoclonal α-tubulin (ab28439, Abcam), rabbit polyclonal anti-TOMM20 (sc-11415, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX), mouse monoclonal anti-DIABLO (NB500-213, Novus Biologicals, Inc., Littleton, CO), rabbit polyclonal anti-ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 2 (ENTPD2) (ABIN1385820, Antibodies-online, Inc., Atlanta, GA), rabbit polyclonal anti-acyl-CoA thioesterase 2 (ACOT2) (ABIN405459, Antibodies-online Inc.), rabbit polyclonal anti- hexose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (H6PD) (ab170895, Abcam), rabbit polyclonal anti-coproporphyrinogen-III oxidase (CPOX) (ab102938, Abcam), rabbit polyclonal anti-COX4I1 (ABIN310391, Antibodies-online Inc.), rabbit polyclonal anti-cytochrome b5 type A (CYB5A) (ABIN1529444, Antibodies-online Inc.), horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG (sc-2033, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), goat anti-rabbit IgG (sc-2004, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or goat anti-mouse IgG (sc-2005, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The western blot was visualized with an ECL Western blot system (Pierce).

Oxygen Consumption Rate (OCR) Measurement

OCR was measured using an XF24 Extracellular Flux Analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience, Billerica, MA) as described in the manufacturer's instruction. Briefly, hepa1c1c7 cells were plated in growth medium at 20,000 cells/well and c12 cells at 40,000 cells/well. After 24 h, the culture medium was replaced with specific XF24 assay medium containing TCDD (10 nM or 30 nM) or 0.03% DMSO (vehicle control). XF24 assay medium consisted of DMEM base (#D5030, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 25 mM glucose, 31 mM sodium chloride, 1 mM sodium pyruvate (#11360, Gibco), 2 mM GlutaMAX (#35050, Gibco), and 15 mg/L phenol red (#P3532, Sigma-Aldrich). Measurement of OCR started 90 min after switching to XF24 assay medium containing TCDD or DMSO and the inhibitors of ETC and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) system were injected in the following order: oligomycin A (0.5 μM), Carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone (FCCP) (1.0 μM for 1c1c7 and 0.5 μM for c12 cells), and antimycin A (0.5 μM). The concentrations of inhibitors for each cell line were optimized by measuring OCR in XF24 assay medium. The OCR (picomoles per minute) was divided by the number of cells plated for each well and parameters related to mitochondrial function were calculated using the manufacture's software, XF Mito Stress Test Report Generator, and an equation previously published (Brand and Nicholls, 2011). Using Originpro8, analysis of variance (One-way ANOVA) followed by Tukey's post hoc test was used to assess potential for differences in the respiratory parameters.

Stable Isotopic Labeling by Amino Acids in Cell Culture (SILAC) and Quantitative Proteomic Analysis

Preparation of mitochondrial proteins

Cells were grown in SILAC™-DMEM supplemented with 10% dialyzed fetal bovine serum, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 μg/mL L-arginine, and 100 μg/mL L-lysine (light L-lysine HCl/L-arginine, medium 13C6L-lysine HCl/15N4-L-arginin, or heavy 13C615N2L-lysine HCl/13C615N4L-arginine (SILAC™ media kit, Invitrogen and Cambridge Isotope Laboratories)) for 5 cell doublings to insure full incorporation of labeled amino acids into cellular proteins. Cells were then treated with 10 nM TCDD or 0.01% DMSO (vehicle control) for 72 h. Treated cells were harvested and mitochondrial fractions were isolated as described above. After protein quantification, equal amount of proteins (35 μg) labeled with light, medium, or heavy amino acids within one experimental set were combined. When samples from the four independent experimental were collected, proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE.

Mass spectrometry (MS)

SDS-PAGE gels were divided into 10 equal slices, and each slice was digested with trypsin by in-gel digestion according to Shevchenko, et al. with modifications (Shevchenko et al., 1996). Peptides were extracted from the gel and dissolved in 2% acetonitrile/0.1% trifluoroacetic acid. Peptides were automatically injected by a Thermo EASYnLC 1000 onto a Thermo Acclaim PepMap RSLC 0.075mm × 250mm C18 column (Buffer A = 99.9% Water/0.1% Formic Acid, Buffer B = 99.9% Acetonitrile/0.1% Formic Acid) and eluted over 90 min with a gradient of 2% B to 30% B in 79 min, ramping to 100% B at 80 min and held at 100% B for the duration of the run. Eluted peptides were sprayed into a ThermoFisher Q-Exactive mass spectrometer using a FlexSpray spray ion source. Survey scans were taken in the Orbi trap (70,000 resolution, determined at m/z 200) and the top ten ions in each survey scan were then subjected to automatic higher energy collision induced dissociation (HCD) with fragment spectra acquired at 17,500 resolution.

Data analysis

The resulting MS/MS spectra were converted to peak lists using MaxQuant, v1.4.1.2 (www.maxquant.org), searched against a database containing Uniprot Mouse protein sequences (www.uniprot.org), and appended with common laboratory contaminants using the Andromeda search algorithm, a part of the MaxQuant environment (Cox and Mann, 2008; Cox et al., 2011). Assignments validated using the MaxQuant maximum 1% false discovery rate (FDR) confidence filter are considered true. Andromeda parameters for all databases were as follows: quantification triple SILAC labeling: light (Arg0, Lys0), medium (Arg4, Lys6), heavy (Arg10, Lys8); allowing maximum 2 missed trypsin sites, fixed modification of carbamidomethyl cysteine, variable modification of oxidation of methionine; peptide tolerance of +/− 5 ppm, fragment ion tolerance of 0.3 Da and FDR calculated using randomized database search. From each quantified SILAC labeling, three isotope ratios were calculated in each independent experiment. To ensure that each independent set provided similar results, ratios from identical treatments and the same cell lines between each independent set were compared with a Pearson's Correlation Coefficient (rp). Briefly, the ratios of an identical protein were matched from two independent sets for the same cell type, 1c1c7 or c12, which were exposed to the same treatment; undetected proteins in either independent set were removed prior to further analysis. Data from the matched independent sets were log-transformed and checked with a histogram and QQ plot prior to correlation to ensure comparison of normal distributions. Pearson's Correlation Coefficients were ≥ 0.47 in comparing identical protein ratios amongst identical treatments between the 4 independent samples sets. Subsequently, data were combined and averaged across all independent sets to obtain a triplicate measurement for each treatment and each cell type. The ratios (n=3) were averaged to obtain mean fold changes for all detected proteins. Mean |fold changes| ≥ 2 were considered significant. Significant mean fold changes of identical proteins from differing treatments were matched and, subsequently, compared with a Student's t-test with the Benjamini-Hochberg multiple comparison correction to assess type I error. Adjusted p-values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant. Python version 2.7.6 was used for all data processing and R version 3.0.2 (R Core Team, 2013) was used for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

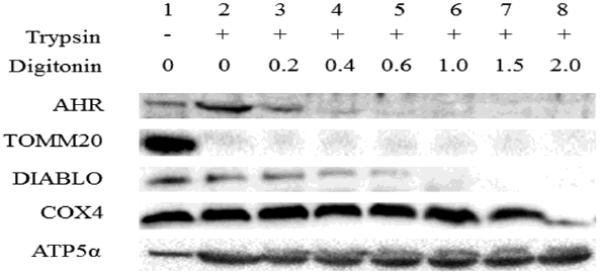

Identification of a Mitochondrial Compartment of AHR Location in Mitochondria

To examine the sub-compartmental localization of AHR within the mitochondria, protease protection and digitonin extraction assays were performed. Mitochondria from hepa1c1c7 cells were treated with trypsin in the absence and presence of increasing concentrations of digitonin and, subsequently, a western blot was performed to detect mitochondrial proteins (Figure 1). In the presence of trypsin alone, the outer-membrane marker protein TOMM20 was not detected while AHR was present, suggesting that the cytosolic AHR is not nonspecifically bound to the outer-membrane of the mitochondria. Upon the addition of increasing amounts of digitonin, the AHR was lost from the pellet in a similar pattern as the inter-membrane space (IMS) marker DIABLO suggesting that most of the AHR is found in the IMS. The inner-membrane marker, COX4, and matrix marker protein, ATP5α, remained after the AHR and DIABLO signal were absent suggesting that the AHR is within the inter-membrane space.

Figure 1. Mitochondrial sub-compartment analysis for AHR localization.

Accessibility of trypsin to proteins within isolated mitochondria from hepa1c1c7 cells following exposure to increasing concentration of digitonin (0.0–2.0 mg of digitonin/mg of protein) was evaluated. Proteins that remained in mitochondrial pellets were analyzed by Western blotting. TOMM20 was used as an outer-membrane marker. DIABLO was an inter-membrane space (IMS)-localized protein. Cytochrome c oxidase subunit IV (COX4) was a mitochondrial inner-membrane protein and ATP5α was a mitochondrial matrix protein. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments.

To further explore the mitochondrial localization of the mitoAHR, hepa1c1c7 cells were treated with 0.01% DMSO (vehicle control) or 10 nM TCDD. In the presence of DMSO, the mitoAHR was localized to the IMS confirming the results from naïve cells (lane 1–3, Figure 2A and B). TCDD exposure for 6 h decreased the level of AHR within the IMS compared to the DMSO-treated controls suggesting that AHR ligands can impact the mitochondrial localization of the receptor (lane 4–6, Figure 2A). Similar results were observed following 24 h of TCDD exposure (Figure 2B). In addition, the overall level of mitoAHR was also decreased by TCDD exposure (compare lane 1 and 4, Figure 2A and B). This corresponded to the decreased level of cytosolic AHR isolated from the same cells exposed to TCDD (Figure 2C). Thus, TCDD exposure decreased the cytosolic and mitochondrial pools of the AHR.

Figure 2. mitoAHR is susceptible to ligand-induced degradation.

Hepa1c1c7 were exposed to DMSO (0.01%) or TCDD (10 nM) for 6 (A) or 24 h (B). Isolated mitochondria were trypsinized (lane 2, 3, 5 and 6) in the absence (Lane 1, 2, 4, and 5) or presence of digitonin (0.4 mg of digitonin/mg of protein, lane 3 and 6). Proteins that remained in mitochondrial pellets were analyzed by Western blotting. TOMM20 was used as an outer-membrane marker. DIABLO was an IMS-localized protein. ATP5α was a mitochondrial matrix protein. Cytosolic proteins (C) were included to assess level of TCDD-induced AHR degradation for 6 or 24 h. α-tubulin was a cytosolic marker. D: DMSO, T: TCDD. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments.

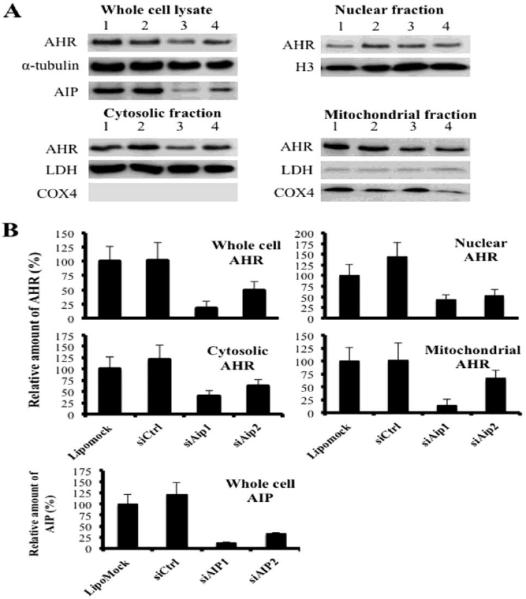

Change in AHR Expression by AIP Knockdown and HSP90 inhibition

Mitochondrial proteins lacking a classic MTS can be targeted to TOMM20 by cytosolic chaperones, such as HSP90 and AIP (Budas et al., 2010; Kang et al., 2011; Rodriguez-Sinovas et al., 2006; Yano et al., 2003). To test whether AIP is involved in mitochondrial AHR import, AIP was knocked down in hepa1c1c7 cells using siRNA. AHR expression in each subcellular fraction was analyzed by Western blotting and densitometry (Figure 3). The level of AIP expression was decreased approximately by 85% and 65% by siAip1 and siAip2, respectively, when compared to a lipomock control (transfectant control) in whole cell lysate. The AIP knockdown by siAip2 was less efficient than siAip1, which, subsequently, caused different degrees in AHR destabilization in cellular fractions. The level of AHR expression in whole cell lysate was decreased by 80% by siAip1 and 50% by siAip2, respectively. The levels of cytosolic and nuclear AHR were also decreased by 40–60% upon transfection of siAip1 and siAip2. The level of mitoAHR was decreased by approximately 85% by siAip1 and 40% by siAip2. These results suggest that the AHR was destabilized by knockdown of the AIP in all cellular fractions, not specifically mitoAHR. Furthermore, HSP90 is also involved in the trafficking of proteins into the mitochondria, especially those having an internal targeting sequence. HSP90, therefore, was examined for its potential role in mitochondrial AHR localization. Inhibition of HSP90 ATPase by geldanamycin decreased the level of AHR in all cellular fractions, not specifically the level of mitoAHR, similar to the results following knockdown of the AIP (data not shown). Therefore, both chaperones, AIP and HSP90, are critical for the protein levels of both cytosolic and mitochondrial AHR.

Figure 3. The effect of AIP knockdown on the amount of AHR in cellular fractions of hepa1c1c7 cells.

siRNA was used to knockdown AIP in Hepa1c1c7 cells. Western blot analysis for AIP and AHR expression was performed from whole cell lysate, and nuclear, cytosolic, and mitochondrial fractions. α-tubulin was used as a loading control for the whole cell lysate, histone H3 (H3) was a loading control for the nuclear fraction, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was a loading control for the cytosolic fraction, and cytochrome c oxidase subunit IV (COX4) was a loading control for the mitochondrial fraction. (A) Results shown are representative of 3 independent experiments. Lane 1: lipofectamine treatment (Lipomock), lane 2: 10 nM Silencer® Select Negative Control #1 siRNA (siCtrl), lane 3: 10 nM siRNA1 for AIP (siAIP1), lane4: 10 nM siRNA2 for AIP (siAIP2). (B) Densitometry was determined with a Fuji Image analyzer. The levels of expressions of AIP and AHR protein were normalized to each loading control. The normalized protein expression levels were compared with each other by re-normalization with the protein expression from which cells were affected by lipofectamine only (Lipomock). The bars represent mean ± the standard errors (n=3).

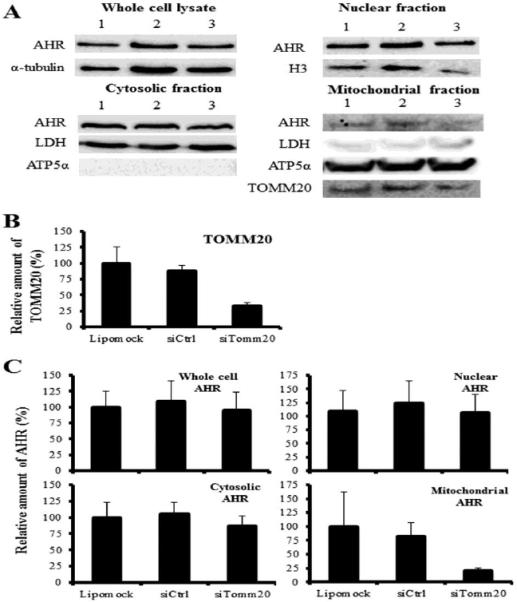

Change in AHR Expression by TOMM20 Knockdown

TOMM20 was knocked down in hepa1c1c7 cells using siRNA to test its potential involvement in the import of the AHR into the mitochondria. Following the knockdown, the level of expression of AHR in each subcellular fraction was examined by western blot analysis and densitometry (Figure 4). The level of TOMM20 expression in the mitochondria was decreased by approximately 70% in siTomm20-transfected cells compared to a lipomock control (transfectant control) (Figure 4B). The amount of mitoAHR was also decreased by approximately 70% following siTomm20 transfection compared to a lipomock control (Figure 4C). In contrast, there was no change in the level of AHR in the cytosol, nuclear fraction or whole cell lysate following knockdown of TOMM20. These results suggest that TOMM20 is involved in mitochondrial localization of the AHR.

Figure 4. The effect of TOMM20 knockdown on the amount of AHR protein in cellular fractions of hepa1c1c7 cells.

siRNA was used to knockdown TOMM20 in Hepa1c1c7 cells. Western blot analysis for TOMM20 and AHR expression was performed from whole cell lysate, and nuclear, cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions. α-tubulin was used as a loading control for the whole cell lysate, histone H3 (H3) was a loading control for the nuclear fraction, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was a loading control for the cytosolic fraction and ATP5α was a loading control for the mitochondrial fraction. (A) Results shown are representative of three independent experiments. Lane 1: lipofectamine treatment (Lipomock), lane 2: 10 nM nontargeting siRNA (siCtrl), lane 3: 10 nM siRNA for TOMM20 (siTomm20). (B and C) Densitometry was determined with a Fuji Image analyzer. The expressions of TOMM20 and AHR protein were normalized to each loading control. The normalized protein expression levels were compared to each other by re-normalization with the protein expression from which cells were affected by lipofectamine only (Lipomock). The bars represent mean ± the standard errors (n=3).

Cellular Respiration in Mouse Hepatoma Cells under TCDD Exposure

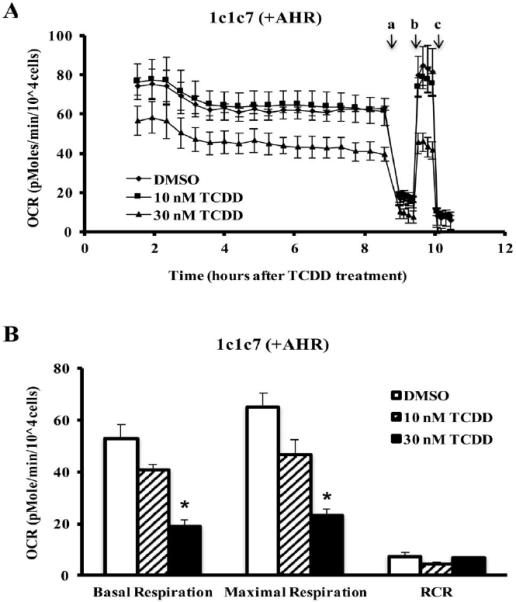

The results presented suggest that a fraction of intracellular AHR can be found within the IMS of the mitochondria. Previous research has demonstrated that AHR ligands can impact mitochondrial function by modifying mitochondrial membrane potential and ETC activities (Senft et al., 2002a; Senft et al., 2002b; Shen et al., 2005; Tappenden et al., 2011). To further explore the role of the AHR and AHR ligands in mitochondrial homeostasis, the oxygen consumption rates (OCRs) of two mouse hepatoma cell lines, 1c1c7 (AHR-expressing) and c12 (AHR-deficient), were measured. The two cell lines were treated with TCDD (10 or 30 nM) or DMSO (0.01%, vehicle control) and OCR was monitored in the presence of an ATP synthase inhibitor, oligomycin A (a), and an uncoupler, FCCP (b) and a complex III inhibitor, antimycin A (c) (Figure 5A and C). The key parameters of mitochondrial function, basal respiration, maximal respiration, spare respiratory capacity, and respiratory control ratio (RCR) were calculated as described in supplementary table 1. Hepa1c1c7 displayed a TCDD-dose-dependent decrease in basal and maximal respiration that reached significance at 30 nM (Figure 5A and B). The hepac12 cells displayed no difference in basal respiration rates following TCDD exposure (Figure 5C and D). The hepac12 cells exposed to 10 nM or 30 nM TCDD showed a slight increase in maximal respiration rates following TCDD exposure, but these were not significant when compared to that of the DMSO-treated cells. However, this induced a significant increase in the RCR following 30 nM TCDD exposure to hepac12 cells (Figure 5D). There was no significant difference in spare respiratory capacity in either cell line exposed to TCDD (data not shown).

Figure 5. Measurement of oxygen consumption rate (OCR) from hepa1c1c7 and hepac12 cells.

OCR, calculated as (pmole/min/104 cells), in hepa1c1c7 (A) and hepac12 (C) cells exposed to TCDD (10 nM or 30 nM) or vehicle control (DMSO 0.01%) was measured basally or following addition of (a) oligomycin (0.5 μM), (b) FCCP (1 μM for hepa1c1c7 and 0.5 μM for hepac12), and (c) antimycin A (0.5 μM). Lines indicate average values ± the standard errors (n=3). Basal respiration and maximal respiration were calculated by manufacturer's software, the XF Mito Stress Test Report Generator and respiratory control ratio (RCR) was calculated by the equation mentioned in the Supplementary table 1 for hepa1c1c7 (B) and hepac12 (D) cells. Data were analyzed for significant differences by ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test. A star indicates significant differences at p < 0.05 when compared to vehicle control.

The difference in basal/maximal respiration between cell lines exposed to 30 nM TCDD led us to speculate that cytochrome c oxidase, complex IV, may have a decreased efficiency following TCDD exposure as a result of TCDD-induced oxidative stress. Interestingly, 30 nM TCDD exposure did not significantly alter the activities of ETC complexes or ATP synthase in either cell line though several trended toward modulation (Hwang et al.). This suggests that decreased cellular OCR in hepa1c1c7 cells by TCDD may not be caused by a lack of efficiency in complex IV or other individual component of ETC and ATP synthase. In addition, as TCDD did induce a change in the RCR in hepac12 cells but not hepa1c1c7 cells (Figure 5B and D), the efficiency of OXPHOS may be maintained by AHR during the period (~10 hrs) observed in this study.

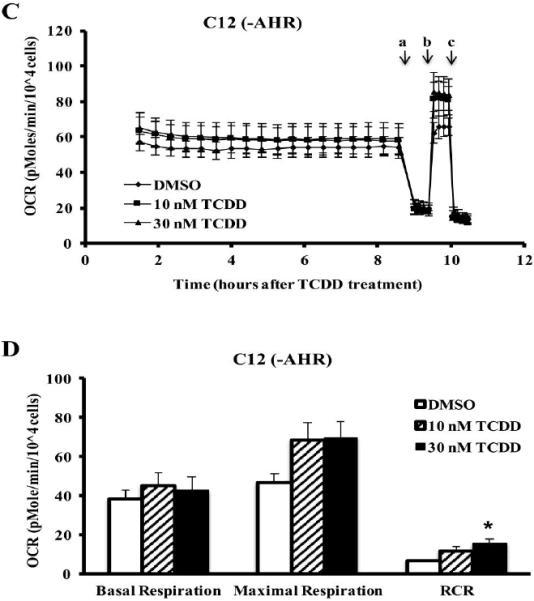

Identification of Proteins Differently Expressed upon TCDD Exposure

Previous reports and the OCR results presented above suggest that the AHR can impact mitochondrial function directly (Senft et al., 2002b; Shen et al., 2005). To determine the role of the AHR-dependent modulation of mitochondrial protein expression, a stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) experiment was performed with exposure of DMSO (0.01%, vehicle control) or TCDD (10 nM) for 72 h. Because prolonged high-dose TCDD exposure can cause cellular death via oxidative stress (Boverhof et al., 2005; Nebert et al., 2000; Seefeld et al., 1984), SILAC-labeled hepa1c1c7 and c12 cells were exposed to only 10 nM TCDD not 30 nM. MaxQuant analysis identified approximately 2,500 independent proteins (Hwang et al.). In matching unique proteins between the hepa1c1c7TCDD/hepa1c1c7DMSO (C7T/C7D) and hepac12TCDD/hepac12DMSO (C12T/C12D) ratio, 1,831 proteins were detected in both datasets. To prioritize the data, proteins were filtered to include only ratios with a |fold change| ≥ 2 in the C7T/C7D ratio; subsequently, 17 proteins were identified which met such criteria. The upregulated proteins included those involved in metabolic pathways (e.g., H6PD, CPOX and CYB5) and the downregulated proteins included those involved in mitochondrial biogenesis (e.g., WARS2 and MRPS28). The expression of 8 of these 17 proteins from C7T/C7D were significantly different when compared to C12T/C12D (Benjamini-Hochberg corrected p ≤ 0.05) (Figure 6). Of these proteins, 5 proteins were upregulated and 3 proteins were downregulated in hepa1c1c7 (Table 1).

Figure 6. SILAC analysis of differentially expressed proteins by TCDD.

The data were filtered for differentially expressed by mean |fold changes| ≥ 2 and Benjamini-Hochberg multiple comparison corrected p ≤ 0.05. Datasets were compared to identify AHR-dependently expressed proteins by TCDD exposure.

Table 1.

Identified proteins differentially regulated by 10 nM TCDD exposure for 72 h in an AHR-dependent manner.

| C7T/C7D VS C12T/C12D | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Name | Gene Name | Entrez number | C7T/C7D Mean Ratio | C12T/C12D Mean Ratio | Adjusted P-value |

| *Ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 2 | Entpd2 | 12496 | 7.413 | 1.196 | 0.029 |

| Tyrosine-protein kinase receptor UFO | Axl | 26362 | 4.569 | 0.772 | 0.106 |

| Tenascin XB | Tnxb | 81877 | 3.416 | 1.273 | 0.034 |

| Retinol-binding protein 4 | Rbp4 | 19662 | 2.859 | 0.926 | 0.004 |

| *Coproporphyrinogen-III oxidase, mitochondrial | Cpox | 12892 | 2.433 | 1.229 | 0.017 |

| *Cytochrome b5 | Cyb5; Cyb5a | 109672 | 2.289 | 0.997 | 0.003 |

| V-type proton ATPase subunit D | Atp6v1d | 73834 | 2.139 | 1.669 | 0.661 |

| Dehydrogenase/reductase SDR family member 1 | Dhrs1 | 52585 | 2.051 | 1.117 | 0.141 |

| *GDH/6PGL endoplasmic bifunctionalprotein;Glucose 1-dehydrogenase;6-phosphogluconolactonase | H6pd | 100198 | 2.025 | 1.252 | 0.051 |

| Collagen alpha-1(XII) chain | Col12a1 | 12816 | 0.448 | 0.989 | 0.039 |

| Tryptophan--tRNA ligase, mitochondrial | Wars2 | 70560 | 0.440 | 1.056 | 0.141 |

| Thioredoxin reductase 1, cytoplasmic | Txnrd1 | 50493 | 0.401 | 0.704 | 0.051 |

| Serine (or cysteine) peptidase inhibitor, clade B, member 9b | Serpinb9b | 20706 | 0.396 | 1.274 | 0.088 |

| 28S ribosomal protein S28, mitochondrial | Mrps28 | 66230 | 0.384 | 0.969 | 0.385 |

| Leukocyte surface antigen CD47 | Cd47 | 16423 | 0.334 | 1.042 | 0.017 |

| Myosin-14 | Myh14 | 71960 | 0.262 | 1.007 | 0.033 |

| FYVE, RhoGEF and PH domain-containing protein 5 | Fgd5 | 232237 | 0.016 | 0.387 | 0.385 |

Note: Proteins included meet fold change (|fold change| ≥ 2) cut-offs.

validated by Western blot analysis.

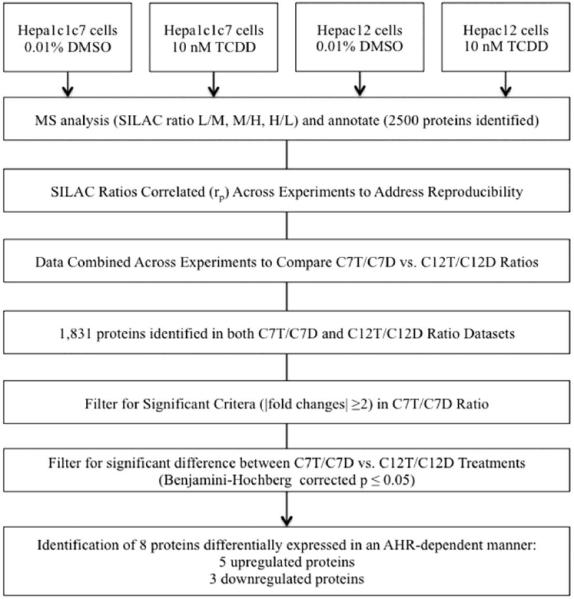

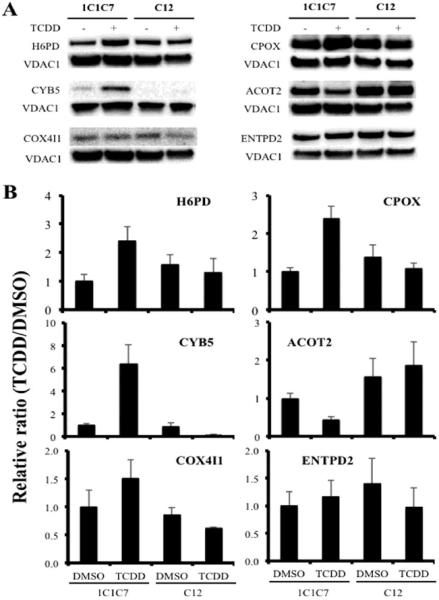

Validation of Proteomic Results

To verify the SILAC-based proteomic quantification, 6 proteins were measured by Western blot analysis (Figure 7). Four upregulated proteins (i.e., H6PD, CPOX, CYB5, and ENTPD2), which were identified in mitochondrial proteomics dataset, were tested (Table 1). ENTPD2 is a demonstrated AHR target gene (Dere et al., 2011). In addition, ACOT2 and COX4I1 proteins were chosen based on previous mRNA expression studies and for a potential role in TCDD-induced changes in mitochondrial function (COX4I1) and dyslipidemia (ACOT2) (Forgacs et al., 2010). Density of each western signal was measured and normalized to the density of the control, VDAC1. Western blot analysis was performed three times independently. The density measured for H6PD, CPOX, CYB5, COX4I1, and ACOT2 expression corresponded to the quantification of MS (Supplementary table 2 and Figure 7). The Western blot analysis of ENTPD2 expression did not agree with the MS data, presumably due to the splice variants and processing of ENTPD2 protein within the cell (Figure 7). The relationship between three independent Western blot analysis and MS data was summarized in Supplementary table 2.

Figure 7. Western blot analysis of differentially expressed proteins identified by SILAC in hepatoma 1c1c7 and c12 cells exposed to DMSO or TCDD.

Western blot was performed on mitochondrial fractions prepared from the two cell lines following exposure to DMSO (0.01%) or TCDD (10 nM). VDAC1 was used as a loading control. (A) Results shown are representative of 3 independent experiments. (B) Densitometry was determined with a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc MP System Image analyzer. Each protein expression was normalized to the loading control. The normalized protein expression levels were compared with each other by re-normalization with the protein expression from hepa1c1c7 cells exposed to DMSO. The bars represent mean ± the standard errors (n=3).

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to demonstrate that a portion of the cellular AHR is found in the mitochondrial IMS. This study also evaluated the AHR-dependent effect of TCDD on oxygen consumption rates and demonstrated that the AHR plays a critical role in regulating mitochondrial homeostasis in response to TCDD-induced stress. Though many mechanistic studies focused on TCDD-induced changes of AHR target gene expression, accumulating research has suggested that AHR-dependent TCDD-induced oxidative stress can result from transcriptional and nontranscriptional responses (Biswas et al., 2008; Matsumura, 2009; Miao et al., 2005; Nebert et al., 2000). Considering that mitochondria are the main site for energy production, the organelle for many critical metabolic pathways, and the main source of ROS, research has now begun focusing on mitochondrial dysfunction as a key factor in TCDD-induced toxicities. Although further studies are necessary to clarify the role of the AHR in the IMS and involvement of mitoAHR in mitochondrial homeostasis by TCDD, the evidence in this study together with the previous studies (Tappenden et al., 2013; Tappenden et al., 2011) suggests that mitoAHR may be important for maintenance of mitochondrial function and TCDD-induced metabolic flux.

We suggest that the cytosolic chaperones, AIP and HSP90, deliver a portion of the cellular AHR to the IMS via TOMM20, which functions as the recognition protein for mitochondrial AHR import. Such a hypothesis is supported by previous studies which show that: 1) AIP, an AHR chaperone, contributes to mitochondrial protein localization via interacting with TOMM20 (Kang et al., 2011; Yano et al., 2003); 2) HSP90, another AHR chaperone, assists the translocation of proteins into the mitochondria (Gava et al., 2011); 3) TOMM20 recognizes N-terminal target sequences of mitochondrial targeted proteins and facilitates their translocation into the IMS (Diekert et al., 1999); and 4) TOMM20 mediates delivery of mitochondrial-targeted proteins by HSP90/HSP70 to TOMM70 (Fan et al., 2011). It should be noted that prediction programs for mitochondrial targeting sequence, such as MitoProtII and MitoFates, and the protein sequence alignment tool, SIM, (Claros and Vincens, 1996; Fukasawa et al., 2015; Huang and Miller, 1991) further support mitochondrial localization of the AHR (data not shown).

The mitochondria-localized ligand-activated receptors and known crosstalk between signaling pathways of the AHR and these receptors suggest that mitoAHR in the IMS contribute to TCDD-induced mitochondrial stress (Demory et al., 2009; Ohtake et al., 2003; Psarra and Sekeris, 2008). Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), a plasma membrane receptor, was found in mitochondrial IMS interacting with the subunit 2 of cytochrome c oxidase (Demory et al., 2009). TCDD-induced AHR activation stimulated cancer cell proliferation by regulating a phosphorylation on Src, a downstream factor of the EGFR (Xie et al., 2012). Inversely, EGFR signaling repressed the expression of an AHR target gene by decreasing binding of p300 coactivator to AHR target gene promoters in normal human cells (Sutter et al., 2009). Steroid/thyroid hormone receptors are also found in the nucleus and mitochondria and, notably, share target genes with AHR (Ohtake et al., 2003; Psarra and Sekeris, 2008). Dioxin-activated AHR enhances breakdown of thyroid hormone and AHR-induced CYP1B1 expression increases metabolism of estrogen receptor ligands (Hayes et al., 1996; Schraplau et al., 2015). Glucocorticoid receptor regulates AHR gene expression and the ligand-activated AHR mediated ubiquitin-mediated degradation of the estrogen receptor-α as described above (Bielefeld et al., 2008; Ohtake et al., 2007). OXPHOS and other mitochondrial function-related genes were differentially regulated by TCDD-induced AHR signaling in female cardiac tissue, which also supports a concept, a sex-hormone-related regulatory mechanism of gene expression for AHR signaling (Carreira et al., 2015).

As a direct or indirect regulator of respiratory efficiency, AHR might create a balance between mitochondrial hyperpolarization and reduced respiration following TCDD exposure to maintain mitochondrial coupling efficiency; notably, the AHR was previously was shown to play a role in maintaining cellular ATP levels for 6 h exposure of TCDD (Tappenden et al., 2011). This is evidenced by the constant RCR in hepa1c1c7 following TCDD exposure. The protein-protein interaction between mitoAHR and ATP5α1 (a component of ATP synthase) and TCDD-induced loss of these interactions also suggest that a pool of mitoAHR possibly causes alterations in chemical gradients or respiratory inefficiency, which could play a role in TCDD-caused oxidative stress (Tappenden et al., 2011). The AHR regulates several pathways that can create electron carriers and modulate cellular redox potential homeostasis (Carreira et al., 2015; Shen et al., 2005); thus, the AHR cannot be ruled out as a regulator of the influx of electrons into ETC to maintain cellular respiration capacity. Recently, a study using skeletal myoblast cells demonstrated that nongenomic AHR signaling generated TCDD-induced mitochondrial toxicities (Biswas et al., 2008). Just as TCDD-induced transcription-independent retrograde signaling from the mitochondria to the nucleus, both genomic and nongenomic AHR signaling would affect mitochondrial toxicities by prolonged TCDD exposure.

Many studies have shown TCDD-induced metabolic dysfunction through alterations in gene expression related to lipid and carbohydrate metabolism and mitochondrial metabolism (Angrish et al., 2011; Boverhof et al., 2005; Forgacs et al., 2010; Forgacs et al., 2013). In addition, proteomic analysis of whole cells identified the mitochondrial outer-membrane protein, voltage-dependent anion channel-selective protein 2, to be upregulated in response to TCDD exposure (Sarioglu et al., 2008). In our SILAC-based mitochondrial proteomic analysis, we identified the proteins that were significantly altered in an AHR-dependent manner following TCDD exposure. These include proteins involved in redox regulation, which is important for cellular energy production. Several proteins involved in heme biosynthesis were also identified. Given that many enzymatic reactions induced by AHR require a heme group as a cofactor (e.g. cytochrome P450) and that several heme metabolites have been suggested to be putative endogenous ligands for the AHR, this observation raises several interesting regulatory possibilities. Our SILAC results support the previous suggested role for the AHR in regulation of cellular energetics and hepatosteatosis. Finally, all of these results suggest that the AHR, alone or through crosstalk with other signaling pathways, induces profound mitochondrial changes at the gene and protein expression levels that are dependent upon the length of TCDD exposure. Therefore, we suggest that the connection between early and later mitochondrial responses following TCDD exposure should to be considered in any future study of AHR-mediated TCDD-induced liver diseases.

In conclusion, the results demonstrate that a portion of the cellular AHR pool can be found within the IMS of the mitochondria. Furthermore, TCDD exposure can induce alterations in mitochondrial function and proteome in an AHR-dependent manner. Similar to the EGFR and the steroid hormone receptors, this implies a role for the AHR in mitochondrial adaptation to stress. Given that the mitochondria play a central role in metabolism, energetics, and induction of oxidative stress, and these processes are altered upon exposure to AHR ligands, it is interesting to hypothesize that mitoAHR is critical for the organelle's response to TCDD-induced stress. To support this hypothesis, it will be important to create reagents and tools to assess mitoAHR's function in the absence of other confounding factors. Hence, further research is needed to suggest, in greater detail, the exact role of mitoAHR in mitochondrial biology and the potential impact of TCDD exposures on mitochondrial function.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

-

■

The mitoAHR is localized in the mitochondrial intermembrane space.

-

■

TOMM20 participates in mitoAHR translocation.

-

■

AHR contributes to the maintenance of respiratory control ratio following TCDD exposure.

-

■

TCDD-induced AHR-dependent changes in the mitochondrial proteome are identified.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We would also like to thank the Research Technology Support Facility in the Michigan State University for performing the Mass Spectrometry and its analysis.

FUNDING This research is supported by the NIH/NIEHS grant P42 ES04911. Dr. J. LaPres is partially supported by MSU AgBioResearch. P. Dornbos is supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Training Grant at Michigan State University (T32 ES007255).

Abbreviations

- ACOT2

acyl-CoA thioesterase 2

- AHR

aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- AIP

AHR-interacting protein

- ARNT

AHR nuclear translocator

- COX4

cytochrome c oxidase subunit 4

- CPOX

coproporphyrinogen-III oxidase

- CYB5

cytochrome b5

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- ENTPD2

ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 2

- ETC

electron transport chain

- H6PD

hexose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase

- HSP

heat shock protein

- IMS

inter-membrane space

- mitoAHR

mitochondrial AHR

- MTS

mitochondrial targeting signal

- OCR

oxygen consumption rate

- OXPHOS

oxidative phosphorylation

- PAS

Per-Arnt-Sim

- RCR

respiratory control ratio

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SILAC

stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture

- TCDD

2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin

- TOMM

translocase of the outer-mitochondrial membrane.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Aly HA, Domenech O. Cytotoxicity and mitochondrial dysfunction of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) in isolated rat hepatocytes. Toxicol. Lett. 2009;191(1):79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.08.008. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angrish MM, Jones AD, Harkema JR, Zacharewski TR. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated induction of Stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 alters hepatic fatty acid composition in TCDD-elicited steatosis. Toxicol. Sci. 2011;124(2):299–310. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr226. 10.1093/toxsci/kfr226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal S, Leu AN, Gonzalez FJ, Guengerich FP, Chowdhury AR, Anandatheerthavarada HK, Avadhani NG. Mitochondrial targeting of cytochrome P450 (CYP) 1B1 and its role in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-induced mitochondrial dysfunction. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289(14):9936–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.525659. 10.1074/jbc.M113.525659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielefeld KA, Lee C, Riddick DS. Regulation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor expression and function by glucocorticoids in mouse hepatoma cells. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2008;36(3):543–51. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.019703. 10.1124/dmd.107.019703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas G, Srinivasan S, Anandatheerthavarada HK, Avadhani NG. Dioxin-mediated tumor progression through activation of mitochondria-to-nucleus stress signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105(1):186–91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706183104. 10.1073/pnas.0706183104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boverhof DR, Burgoon LD, Tashiro C, Chittim B, Harkema JR, Jump DB, Zacharewski TR. Temporal and dose-dependent hepatic gene expression patterns in mice provide new insights into TCDD-Mediated hepatotoxicity. Toxicol. Sci. 2005;85(2):1048–63. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi162. 10.1093/toxsci/kfi162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand MD, Nicholls DG. Assessing mitochondrial dysfunction in cells. Biochem. J. 2011;435(2):297–312. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110162. 10.1042/BJ20110162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budas GR, Churchill EN, Disatnik MH, Sun L, Mochly-Rosen D. Mitochondrial import of PKCepsilon is mediated by HSP90: a role in cardioprotection from ischaemia and reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc. Res. 2010;88(1):83–92. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq154. 10.1093/cvr/cvq154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carreira VS, Fan Y, Kurita H, Wang Q, Ko CI, Naticchioni M, Jiang M, Koch S, Zhang X, Biesiada J, Medvedovic M, Xia Y, Rubinstein J, Puga A. Disruption of Ah Receptor Signaling during Mouse Development Leads to Abnormal Cardiac Structure and Function in the Adult. PloS one. 2015;10(11):e0142440. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142440. 10.1371/journal.pone.0142440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver LA, LaPres JJ, Jain S, Dunham EE, Bradfield CA. Characterization of the Ah receptor-associated protein, ARA9. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273(50):33580–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claros MG, Vincens P. Computational method to predict mitochondrially imported proteins and their targeting sequences. Eur. J. Biochem. 1996;241(3):779–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J, Mann M. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26(12):1367–72. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1511. 10.1038/nbt.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J, Neuhauser N, Michalski A, Scheltema RA, Olsen JV, Mann M. Andromeda: a peptide search engine integrated into the MaxQuant environment. J. Proteome Res. 2011;10(4):1794–805. doi: 10.1021/pr101065j. 10.1021/pr101065j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demory ML, Boerner JL, Davidson R, Faust W, Miyake T, Lee I, Huttemann M, Douglas R, Haddad G, Parsons SJ. Epidermal growth factor receptor translocation to the mitochondria: regulation and effect. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284(52):36592–604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.000760. 10.1074/jbc.M109.000760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dere E, Lee AW, Burgoon LD, Zacharewski TR. Differences in TCDD-elicited gene expression profiles in human HepG2, mouse Hepa1c1c7 and rat H4IIE hepatoma cells. BMC genomics. 2011;12:193. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-193. 10.1186/1471-2164-12-193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diani-Moore S, Ram P, Li X, Mondal P, Youn DY, Sauve AA, Rifkind AB. Identification of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor target gene TiPARP as a mediator of suppression of hepatic gluconeogenesis by 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin and of nicotinamide as a corrective agent for this effect. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285(50):38801–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.131573. 10.1074/jbc.M110.131573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diani-Moore S, Zhang S, Ram P, Rifkind AB. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation by dioxin targets phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) for ADP-ribosylation via 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD)-inducible poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (TiPARP) J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288(30):21514–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.458067. 10.1074/jbc.M113.458067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diekert K, Kispal G, Guiard B, Lill R. An internal targeting signal directing proteins into the mitochondrial intermembrane space. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96(21):11752–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.11752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan AC, Kozlov G, Hoegl A, Marcellus RC, Wong MJ, Gehring K, Young JC. Interaction between the human mitochondrial import receptors Tom20 and Tom70 in vitro suggests a chaperone displacement mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286(37):32208–19. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.280446. 10.1074/jbc.M111.280446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgacs AL, Burgoon LD, Lynn SG, LaPres JJ, Zacharewski T. Effects of TCDD on the expression of nuclear encoded mitochondrial genes. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2010;246(1–2):58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2010.04.006. 10.1016/j.taap.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgacs AL, Dere E, Angrish MM, Zacharewski TR. Comparative analysis of temporal and dose-dependent TCDD-elicited gene expression in human, mouse, and rat primary hepatocytes. Toxicol. Sci. 2013;133(1):54–66. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kft028. 10.1093/toxsci/kft028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frezza C, Cipolat S, Scorrano L. Organelle isolation: functional mitochondria from mouse liver, muscle and cultured fibroblasts. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2(2):287–95. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.478. 10.1038/nprot.2006.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukasawa Y, Tsuji J, Fu SC, Tomii K, Horton P, Imai K. MitoFates: improved prediction of mitochondrial targeting sequences and their cleavage sites. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2015;14(4):1113–26. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M114.043083. 10.1074/mcp.M114.043083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gava LM, Goncalves DC, Borges JC, Ramos CH. Stoichiometry and thermodynamics of the interaction between the C-terminus of human 90kDa heat shock protein Hsp90 and the mitochondrial translocase of outer membrane Tom70. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2011;513(2):119–25. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.06.015. 10.1016/j.abb.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griparic L, van der Bliek AM. Assay and properties of the mitochondrial dynamin related protein Opa1. Methods Enzymol. 2005;404:620–31. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)04054-1. 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)04054-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes CL, Spink DC, Spink BC, Cao JQ, Walker NJ, Sutter TR. 17 beta-estradiol hydroxylation catalyzed by human cytochrome P450 1B1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996;93(18):9776–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heid SE, Pollenz RS, Swanson HI. Role of heat shock protein 90 dissociation in mediating agonist-induced activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 2000;57(1):82–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Miller W. A time-efficient, linear-space local similarity algorithm. Adv. Appl. Math. 1991;12(3):337–357. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0196-8858(91)90017-D. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang HJ, Dornbos P, LaPres JJ. AHR-dependent changes in the mitochondrial proteome in response to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Data in BriefSubmitted. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2016.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang HJ, Steidemann M, Dunivin TK, Rizzo M, LaPres JJ. AHR-dependent, 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD)-induced changes in mouse hepatoma electron transport chain and ATP synthase complexes. Data in BriefSubmitted. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2016.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang BH, Xia F, Pop R, Dohi T, Socolovsky M, Altieri DC. Developmental control of apoptosis by the immunophilin aryl hydrocarbon receptor-interacting protein (AIP) involves mitochondrial import of the survivin protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286(19):16758–67. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.210120. 10.1074/jbc.M110.210120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy LH, Sutter CH, Leon Carrion S, Tran QT, Bodreddigari S, Kensicki E, Mohney RP, Sutter TR. 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin-mediated production of reactive oxygen species is an essential step in the mechanism of action to accelerate human keratinocyte differentiation. Toxicol. Sci. 2013;132(1):235–49. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfs325. 10.1093/toxsci/kfs325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaPres JJ, Glover E, Dunham EE, Bunger MK, Bradfield CA. ARA9 modifies agonist signaling through an increase in cytosolic aryl hydrocarbon receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275(9):6153–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.9.6153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1951;193(1):265–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Cui W, Klaassen CD. Nrf2 protects against 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD)-induced oxidative injury and steatohepatitis. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2011;256(2):122–35. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2011.07.019. 10.1016/j.taap.2011.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal PK. Dioxin: a review of its environmental effects and its aryl hydrocarbon receptor biology. J. Comp. Physiol. B. 2005;175(4):221–30. doi: 10.1007/s00360-005-0483-3. 10.1007/s00360-005-0483-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura F. The significance of the nongenomic pathway in mediating inflammatory signaling of the dioxin-activated Ah receptor to cause toxic effects. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2009;77(4):608–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.10.013. 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh BE, Hogenesch JB, Bradfield CA. Mammalian Per-Arnt-Sim proteins in environmental adaptation. Annual review of physiology. 2010;72:625–45. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135922. 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao W, Hu L, Scrivens PJ, Batist G. Transcriptional regulation of NF-E2 p45-related factor (NRF2) expression by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor-xenobiotic response element signaling pathway: direct cross-talk between phase I and II drug-metabolizing enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280(21):20340–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412081200. 10.1074/jbc.M412081200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebert DW, Roe AL, Dieter MZ, Solis WA, Yang Y, Dalton TP. Role of the aromatic hydrocarbon receptor and [Ah] gene battery in the oxidative stress response, cell cycle control, and apoptosis. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2000;59(1):65–85. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00310-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtake F, Baba A, Takada I, Okada M, Iwasaki K, Miki H, Takahashi S, Kouzmenko A, Nohara K, Chiba T, Fujii-Kuriyama Y, Kato S. Dioxin receptor is a ligand-dependent E3 ubiquitin ligase. Nature. 2007;446(7135):562–6. doi: 10.1038/nature05683. 10.1038/nature05683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtake F, Takeyama K, Matsumoto T, Kitagawa H, Yamamoto Y, Nohara K, Tohyama C, Krust A, Mimura J, Chambon P, Yanagisawa J, Fujii-Kuriyama Y, Kato S. Modulation of oestrogen receptor signalling by association with the activated dioxin receptor. Nature. 2003;423(6939):545–50. doi: 10.1038/nature01606. 10.1038/nature01606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psarra AM, Sekeris CE. Steroid and thyroid hormone receptors in mitochondria. IUBMB life. 2008;60(4):210–23. doi: 10.1002/iub.37. 10.1002/iub.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team . R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2013. http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Sinovas A, Boengler K, Cabestrero A, Gres P, Morente M, Ruiz-Meana M, Konietzka I, Miro E, Totzeck A, Heusch G, Schulz R, Garcia-Dorado D. Translocation of connexin 43 to the inner mitochondrial membrane of cardiomyocytes through the heat shock protein 90-dependent TOM pathway and its importance for cardioprotection. Circ. Res. 2006;99(1):93–101. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000230315.56904.de. 10.1161/01.RES.0000230315.56904.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarioglu H, Brandner S, Haberger M, Jacobsen C, Lichtmannegger J, Wormke M, Andrae U. Analysis of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin-induced proteome changes in 5L rat hepatoma cells reveals novel targets of dioxin action including the mitochondrial apoptosis regulator VDAC2. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2008;7(2):394–410. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700258-MCP200. 10.1074/mcp.M700258-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schraplau A, Schewe B, Neuschafer-Rube F, Ringel S, Neuber C, Kleuser B, Puschel GP. Enhanced thyroid hormone breakdown in hepatocytes by mutual induction of the constitutive androstane receptor (CAR, NR1I3) and arylhydrocarbon receptor by benzo[a]pyrene and phenobarbital. Toxicology. 2015;328:21–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2014.12.004. 10.1016/j.tox.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seefeld MD, Corbett SW, Keesey RE, Peterson RE. Characterization of the wasting syndrome in rats treated with 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Toxicology and applied pharmacology. 1984;73(2):311–22. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(84)90337-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senft AP, Dalton TP, Nebert DW, Genter MB, Hutchinson RJ, Shertzer HG. Dioxin increases reactive oxygen production in mouse liver mitochondria. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2002a;178(1):15–21. doi: 10.1006/taap.2001.9314. 10.1006/taap.2001.9314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senft AP, Dalton TP, Nebert DW, Genter MB, Puga A, Hutchinson RJ, Kerzee JK, Uno S, Shertzer HG. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen production is dependent on the aromatic hydrocarbon receptor. Free radical biology & medicine. 2002b;33(9):1268–78. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01014-6. S0891584902010146 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen D, Dalton TP, Nebert DW, Shertzer HG. Glutathione redox state regulates mitochondrial reactive oxygen production. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280(27):25305–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500095200. 10.1074/jbc.M500095200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shertzer HG, Genter MB, Shen D, Nebert DW, Chen Y, Dalton TP. TCDD decreases ATP levels and increases reactive oxygen production through changes in mitochondrial F(0)F(1)-ATP synthase and ubiquinone. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2006;217(3):363–74. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.09.014. 10.1016/j.taap.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevchenko A, Wilm M, Vorm O, Mann M. Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Chem. 1996;68(5):850–8. doi: 10.1021/ac950914h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutter CH, Yin H, Li Y, Mammen JS, Bodreddigari S, Stevens G, Cole JA, Sutter TR. EGF receptor signaling blocks aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated transcription and cell differentiation in human epidermal keratinocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(11):4266–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900874106. 10.1073/pnas.0900874106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tappenden DM, Hwang HJ, Yang L, Thomas RS, Lapres JJ. The Aryl-Hydrocarbon Receptor Protein Interaction Network (AHR-PIN) as Identified by Tandem Affinity Purification (TAP) and Mass Spectrometry. J. Toxicol. 2013;2013:279829. doi: 10.1155/2013/279829. 10.1155/2013/279829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tappenden DM, Lynn SG, Crawford RB, Lee K, Vengellur A, Kaminski NE, Thomas RS, LaPres JJ. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor interacts with ATP5alpha1, a subunit of the ATP synthase complex, and modulates mitochondrial function. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2011;254(3):299–310. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2011.05.004. 10.1016/j.taap.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vengellur A, LaPres JJ. The role of hypoxia inducible factor 1alpha in cobalt chloride induced cell death in mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Toxicol. Sci. 2004;82(2):638–46. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfh278. 10.1093/toxsci/kfh278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie G, Peng Z, Raufman JP. Src-mediated aryl hydrocarbon and epidermal growth factor receptor cross talk stimulates colon cancer cell proliferation. American journal of physiology. Gastrointestinal and liver physiology. 2012;302(9):G1006–15. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00427.2011. 10.1152/ajpgi.00427.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang TT, Hsu CT, Kuo YM. Cell-derived soluble oligomers of human amyloid-beta peptides disturb cellular homeostasis and induce apoptosis in primary hippocampal neurons. Journal of neural transmission. 2009;116(12):1561–9. doi: 10.1007/s00702-009-0311-0. 10.1007/s00702-009-0311-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano M, Terada K, Mori M. AIP is a mitochondrial import mediator that binds to both import receptor Tom20 and preproteins. J. Cell Biol. 2003;163(1):45–56. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200305051. 10.1083/jcb.200305051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.